No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

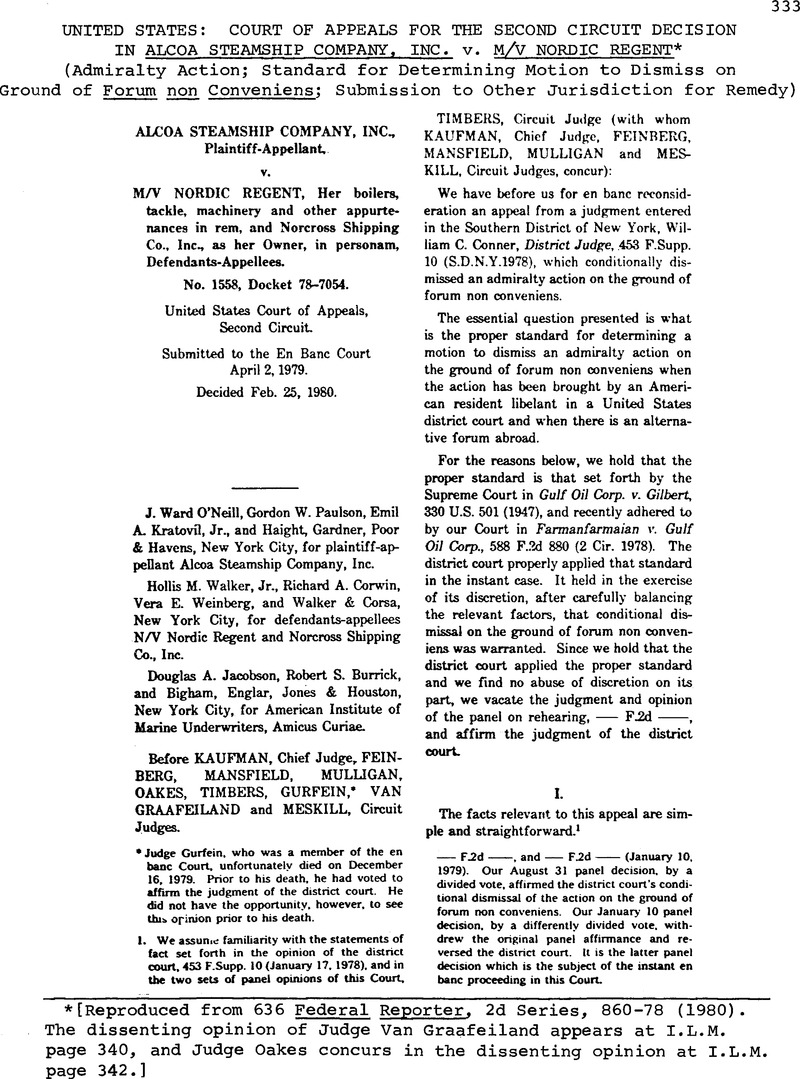

United States: Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Decision in Alcoa Steamship Company, Inc. v. M/V Nordic Regent*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1981

Footnotes

[Reproduced from 636 Federal Reporter, 2d Series, 860-78 (1980). The dissenting opinion of Judge Van Graafeiland appears at I.L.M. page 340, and Judge Oakes concurs in the dissenting opinion at I.L.M. page 342.]

References

2. We believe that it is neither necessary nor appropriate to recount in detail the contentions of the parties in the district court or the Gilbert factors relied on by Judge Conner in exercising his discretion tn granting the forum non conveniens motion. They are fully set forth in the district court opinion. Moreover, the issue that triggered the instant en banc proceeding was not whether the judge had abused his discretion, rather, it was the legal issue as to what is the proper standard for determining a motion to dismiss an. admiralty action on the gmund of forum non conveniens. The panel majority, in its January 10, 1979 opinion, held for the first time that the Gilbert standard “does not, and should not. establish the correct standard for determining when American citizens should have access to their country's admiralty courts.” —- F.2d at , . That was the proposition urged by Alcoa in its petition for rehearing addressed to the panel; it was adopted by the panel by a divided vote; and it is the central issue before us in this en banc proceeding.

3. Scottish judges were the originators of the idea that a law court could refuse to hear a case over which it had jurisdiction. The distinction between forum non conveniens and forum non competens in non-admiralty cases first emerged in Scotland about 1845. Braucher. The Inconvenient Federal Forum, 60 Harv.L. Rev. 908, 909 (1947) (hereinafter cited as Braucher). The Englishcourts, however, generally were unsympathetic to the idea. E. g., Clements v. Macauley, 4 Macph. 583, 592-93 (1866). cited in Braucher. supra, at 910. Even at the time of the Supreme Court decision in Gilbert, the English standard for granting a motion to dismiss on the ground of forum non conveniens required a showing that the trial of the case in the chosen forum would be vexatious and oppressive—in effect, the standard urged upon us by appellant in the instant case. Williams v. Green Bay & W. R.R., 326 U.S. 549, 554-55 n.4 (1946).

4. The factors set forth by the Court were the following:

“If the combination and weight of factors requisite to given results are difficult to forecast or state, those to be considered are not difficult to name. An interest tobe considered, and the one likely to be most pressed, is the private interest of the litigant. Important considerations are the relative ease of access to sources of proof: availability of compulsory process for attendance of unwilling, and the cost of obtaining attendance of willing, witnesses; possibility of view of premises, if view would be appropriate to the action; and all other practical problems that make trial of a case easy, expeditious and inexpensive. There may also be questions as to the enforceability of a judgment if one is obtained. The court will weigh relative advantages and obstacles to fair trial. It is often said that the plaintiff may not, by choice of an inconvenient forum, 'vex,’ ‘harass,’ or ‘oppress' the defendant by inflicting upon him expense or trouble not necessary to his own right to pursue his remedy. But unless the balance is strongly in favor of the defendant, the plaintiff's choice of forum should rarely be disturbed.

Factors of public interest also have a place in applying the doctrine. Administrativedifficulties follow for courts when litigation is piled up in congested centers instead of being handled at its origin. Jury duty is a burden that ought not to be imposed upon the people of a community which has no relation to the litigation. In cases which touch the affairs of many persons, there is reason for holding the trial in their view and reach rather than in remote parts of the country where they can learn of it by report only.There is a local interest in having localized controversies de cided at home. There is an appropriateness, too, in having the trial of a diversity case in a forum that is at home with the state law that must govern the case, rather than having a court in some other forum untangle problems in conflict of laws, and in law foreign to itself.” 330 U.S. at 508 09 (footnote omitted).

5. Moreover, the abuse of discretion standard appears to be the same in both cases. Gilbert, 330 U.S. at 508-09; Koster. 330 U.S. at 531-32.

6. Between 1946 and 1953 alone, the UnitedStates concluded nine bilateral treaties (with China, Italy, Ireland, Uruguay, Colombia, Greece, Israel, Ethiopia and Egypt), all of which provided for access to each country's courts on a “national treatment” basis, with eight specifying access on a most-favored-nation basis. Wilson, Access-to-Courts Provisions in U.S. Commercial Treaties, 47 AfflJ. lnfl Law 20, 45 (1953); 20 Harv.lnfl L.J. 404, 411 n.40 (1979) (relevant treaties summarized). Other more recent treaties with similar provisions include Agreement on Trade Relations. Mar. 17, 1978, United States-Hungary. T.I.A.S. No. 8967; Treaty of Friendship, Establishment and Navigation. Feb. 21, 1961, United States-Belgium. 14 U.S.T. 1284, 1289; Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, Oct. 1, 1961. United States-Denmark, 12 U.S.T. 908, 912.

It might be argued that such provisions were not meant to govern a forum non conveniens situation. Protocols to the Danish and Belgian treaties mentioned above, for example, both refer specifically to entitlement to legal aid as being encompassed within the term “access”. But as the Danish protocol makes clear.

“The term ‘access' as used in Article V, paragraph 1, comprehends, among other things, access to free legal aid and right to exemption from providing security for costs and judgment.” 12 U.S.T. at 937 (emphasis added).

Obviously, the protocol does not limit the meaning of access to entitlement to legal aid or privileges relating to security (which themselves are not unrelated to the typical forum non conveniens issue). Nor is such a provision a constant in the treaties mentioned above. The parallel Belgian protocol refers only to legal aid, 14 U.S.T. at 1309. The treaty involved in Farmanfarmaian contained no such protocol provision at all. Further, the argument for a limiting construction of the treaties based on such protocols would conflict with the clearest meaning of access to the courts Such access would have little value if the dour that admits is a revolving one. Finally, the chief flaw in this approach is that it is precisel> contrary to the interpretation of the Iranian treaty reached by this Court in Farmanfarmian.

7. In maritime cases, the transitory nature of the security available to the libelant was thought to justify the application of the forum rei sitae doctrine. Bickel, supra, at 45-46.

8. This is a fortiori so because in admiralty a foreign court usually will be the alternative forum—one of the few remaining areas where 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) is not applicable.

9. The Silver decision prompted Dean McLaughlin to remark: “At long last, the New York Court of Appeals has abandoned this primitive rule.” N.Y.Civ.Prac. Law Rule 327 (McLaughlin, Practice Commentary) (McKinney Supp. 1979).

Another commentator noted at the time of the decision in Silver thatseven states had “flatly ruled that a case may be dismissed despite residence of a party.” (California. Delaware, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oklahoma. Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin). An intermediate appellate court of Florida had gone the other way. 39Brooklyn LRev. 218, 223-24 & nn. 38-39(1972)

10. Of the scattered states which do not follow the doctrine, some have declined to do so because of peculiar provisions of their state constitutions which have been construed to guarantee residents a local forum. E. g., McDonnell- Douglas Corp. v. Lohn, 557 P.2d 373 (Colo. 1976); Chapman v. Southern Ry.. 230 S.C. 210, 95 S.E.2d 170 (1956). As indicated at note 12, infra, there is no such provision where admiralty jurisdiction is concerned. Apparently the only state where the court of last resort has continued to reject the doctrine as a matter of common law is Florida. Houston v. Caldwell, 347 So.2d 1041 (4th Dist.Ct. App. 1977) (residency held not to be key to deciding forum non conveniens motion), rev'd, 359 So.2d 858 (Fla. 1978).

11. The common iaw trend toward liberal application of the doctrine of forum non conveniens has been reflected in legislation which has achieved the same result in several states. E g., Calif.Civ.Proc.Code § 410 30 (West); Wis. Stat. § 262.19. The federal transfer statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) (1976). was the forerunner of the state statutes.