No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

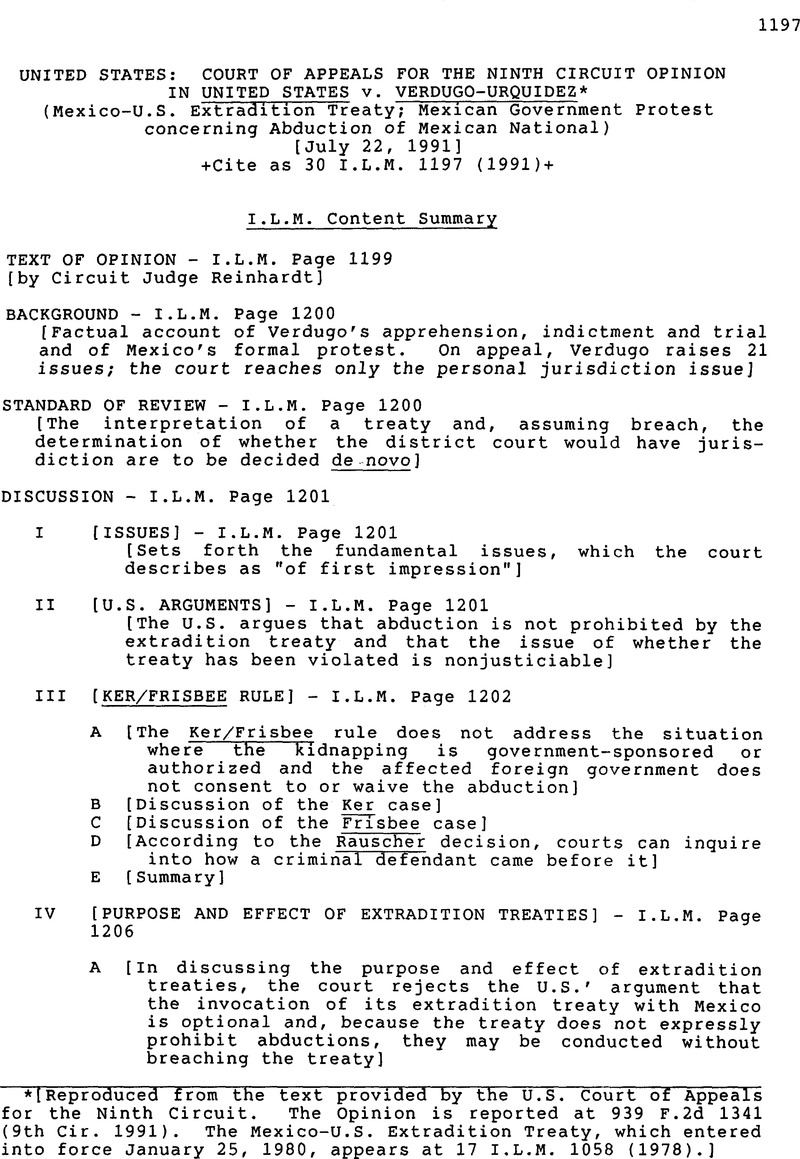

United States: Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit Opinion in United States v. Verdugo- Urquidez (Mexico-U.S. Extradition Treaty; Mexican Government Protest concerning Abduction of Mexican National)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1991

References

* [Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The Opinion is reported at 939 F.2d 1341 (9th Cir. 1991). The Mexico-U.S. Extradition Treaty, which entered into force January 25, 1980, appears at 17 I.L.M. 1058 (1978).]

* On July 31, 1990, we issued an order consolidating this appeal with the appeal of one of Verdugo-Urquidez' co-defendants, Jesus Felix- Gutierrez, No. 89-50028. We dispose of Felix-Gutierrez' appeal in a separate opinion issued concurrently herewith.

1 Subsequently, in a case presenting the identical issue and arising out of the same underlying criminal occurrences, the same district judge, Judge Rafeedie, conducted further legal research on his own, and reached the opposite conclusion. After observing that counsel had been of little assistance to him in resolving the difficult issues involving the law of extradition, he proceeded to write an exhaustive and scholarly opinion on the subject. See United Slates v. CaroQuintero, 745 F. Supp. 599 (C.D.Cal. 1990). In CaroQuintero, Judge Rafeedie concluded that Dr. Albert Machain must be returned to Mexico because his abduction, authorized by the DEA, violated the treaty at issue here. For purposes of clarity, we exclude the decision in CaroQuintero when we refer to relevant prior decisions in this area of the law.

2 government also contends that Verdugo did not properly raise the issue in the court below or in this court. We disagree. The record reflects that Verdugo did indeed raise the issue below. Moreover, our general rule that we do not consider issues raised for the first time on appeal, see, e.g., Winebrenner v. United States, 924 F.2d 851, 856 n.7 (9th Cir. 1991), is itself based on the fundamental notion that “ ‘a federal appellate court does not consider an issue not passed upon below.'” United States v. Patrin, 575 F.2d 708, 712 (9th Cir. 1978) (quoting Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. 106 (1976)) (emphasis added). Here, whether or not Verdugo raised the personal jurisdiction issue below in precisely the same manner that he has framed it on appeal, the district court decided the very issue we now face. Thus, there is no doubt that we may consider the issue on appeal, unless Verdugo somehow forfeited his right to a decision during the appellate process. The government contends that Verdugo waived the issue on appeal by failing to raise it in his opening brief. We disagree for two reasons. First, we conclude that the issue was adequately raised in the opening brief. Second, we have held that an appellant may not raise an issue on appeal in a reply brief if he has failed to discuss it in his opening brief, unless the appellee has raised it in his brief. Eberle v. City of Anaheim, 901 F.2d 814, 818 (9th Cir. 1990). Here, the government clearly addressed the question whether the alleged kidnapping violated the extradition treaty in its brief. To ensure that each side had a fair opportunity to present its views, we instructed the parties to file supplemental briefs and supplemental reply briefs. Having been thoroughly briefed by both sides, the kidnapping issue is squarely before us

3 For example, Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, a wellrespected lawyer and an able former District Attorney, has argued that as a consequence of Ker, no extradition treaty prevents a court of the United States from trying terrorists who have been kidnapped by United States agents abroad. See Specter, How to Make Terrorists Think Twice, N.Y. Times, May 22, 1986, at A31, col. 1.

4 Cook only mentioned Ker in a “compare” citation regarding a commonlaw rule. 288 U.S.at 121.

5 In fact, because the relevant events took place shortly after a revolution, apparently there was no functioning Peruvian government that could have registered a protest. See Kester, 76 Geo. L.J. at 1451

6 For example, as we discuss more fully below, infra at, Article Nine of the United States /Mexico extradition treaty gives each nation the discretion to surrender or not to surrender its own nationals.

7 Equally irrelevant are those cases not involving extradition treaties which refuse to imply an “exclusionary” remedy of suppression of the defendant's person where he was arrested unlawfully. See INS v. LopezMendoza, 468 U.S. 1032, 1039 (1984); United States v. Crews, 445 U.S. 463, 474 (1980); Stone v.Powell, 428 U.S. 564, 485 (1976); Gerstein v.Pugh, 420 U.S. 103, 119 (1975); United States v. Cotten, 471 F.2d 744, 748 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 411 U.S. 936 (1973). As we explain in part IV, infra, extradition treaties set forth mandatory procedures that must be followed in order for a defendant who resides or has taken refuge in another country to be brought to trial in the United States. Therefore, failure to comply with an extradition treaty directly affects the jurisdiction of the court in a way that a typical illegal arrest — even if in violation of the Constitution — does not.

8 See United States v. Lovato, 520 F.2d 1270,1271 (9th Or. 1975) (relying on Ker, Frisbie and Ninth Circuit cases for the proposition “that forcible return to the jurisdiction of the United States constitutes no bar to prosecution once the defendant is found within the United States“)

9 See United States v. Valot, 625 F.2d 308, 310 (9th Cir. 1980) (noting that “individual rights are only derivative through the states” and that ‘Thailand initiated, aided and acquiesced in Valot's removal to the United States“); MattaBallesteros v.Henman, 896 F.2d 255, 260 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 209 (1990) (“Without an official protest, we cannot conclude that Honduras has objected to Matta's arrest. Therefore Matta's claims of violations of international law do not entitle him to relief.“);United State v.Zabaneh, 837 F.2d 1249, 1261 (5th Or. 1988) (“Because neither Guatemala nor Belize protested appellant's detention and removal to the United States, appellant lacks standing to raise the treaties as basis for challenging the court's jurisdiction.“); United States v.Reed, 639 F.2d 896,902 (2d Cir. 1981) (“The fact that the United States has an extradition treaty with the Bahamas does not make any difference at all. The Bahamian government has not sought his return or made any protest …“);United States v. Cordero, 668 F.2d 32, 37 (1st Cir. 1981) (observing that neither “Panama [n]or Venezuela objected to appellants’ departure from their territories“); Waits v. McGowan, 516 F.2d 203, 208 & n.9 (3rd Cir. 1975) ('The pleadings do not allege that Canada has objected in any way to the removal of Waits to this country“).

10 Rauscher provides an example of an implicit rule of specialty, 119 U.S. at 42223, while the Treaty at issue in this case contains an express rule of specialty in Article 17.

11 The Treaty sets forth in its Appendix 31 crimes for which individuals may be extradited.

12 The cases upholding personal jurisdiction over a defendant who claimed to have been kidnapped involve either (1) prior consent or participation by the government of the nation from which the defendant was forcibly removed or expelled, or (2) acquiescence by that government as demonstrated by a subsequent failure to protest. We now categorize the leading cases — including all the cases cited by the government in support of its position — that have upheld jurisdiction over a defendant who was

13 While the Second, Fifth and Sixth Circuits allow a defendant to raise a specialty violation only when the nation from which he has been extradited formally protests, the rule is otherwise in the Eighth, Ninth and Eleventh Circuits. See Leighnor v. Turner, 884 F.2d 385, 388 & n.4 (8th Cir. 1989) (collecting cases). In our circuit, a defendant may raise the objections of the nation from which he has been extradited unless that nation affirmatively consents to a trial on other charges. See Najohn, 785 F.2d at 1422. Our rule appears to be based on the belief that once there has been a formal extradition proceeding in the requested nation, that nation's agreement to extradite only on specific charges must be construed as the equivalent of a formal objection to his trial on other charges. Thus, in specialty cases we do not require an additional formal protest before permitting the defendant to raise the objections of the requested nation. The contrary rule of the Second, Fifth and Sixth Circuits is apparently based on the view that a specific official protest is required after the defendant has been extradited to ensure that the government of the requested nation has not changed its mind and that it still wishes to assert the objection it previously entertained. In any event, the circuit split is not material to the present case, because Mexico has formally protested the treaty violation. Thus, were this a specialty case, Verdugo would be entitled to assert the treaty violation under either rule.

14 The government nonetheless attempts to distinguish the specialty cases by pointing out that the Treaty contains an express specialty provision. As we concluded in part IV(E), supra, this distinction is of no consequence. A defendant has standing to raise specially objections even when a treaty contains no express specialty provision. See Rauscher, 119 U.S. at 424.

15 See, e.g., Clark v.Allen, 331 U.S. 503 (1947) (inheritance rights under treaty with Germany); Bacardi Corp. of America v. Domencech, 311 U.S. 150 (1940) (trademark rights under multilateral treaty); Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U.S. 332 (1924) (right of alien to engage in trade under treaty with Japan); Ware v. Hylton, 3 U.S. 199 (1796) (right to collect private debts under treaty with Great Britain).Cook v.United States, 288 U.S. 102 (1933), is particularly relevant in this regard. Like the present case, Cook involved a seizure, albeit one of property rather than a person. The Court permitted Cook to rely upon a treaty between the United States and Great Britain that regulated the boarding by United States officials of British vessels located in international waters. The Court held that the vessel's seizure and the subsequent imposition of a fine violated the treaty and were therefore unlawful. Id. at 121.

16 In Verdugo I the Court held that the fourth amendment does not apply of its own force to searches and seizures by United States agents of property that is located in a foreign country. Although the Court could have ruled that fourth amendment scrutiny of such extraterritorial searches is barred by the political question doctrine even if the fourth amendment does have extraterritorial effect, the Court instead reached the merits. It then included the language cited in the text regarding the possibility of imposing fourth amendment limitations by treaty.

17 The government also argues that Verdugo may not rely on the Treaty because an implicit term of a treaty can never be selfexecuting. We reject this suggestion. A selfexecuting treaty is one which, of its own force, confers rights on individuals, without the need for any implementing legislation. Rauscher illustrates that an implied term of a treaty may be selfexecuting. As we have stated, supra at, in Rauscher the Supreme Court found an implicit selfexecuting specialty principle. See Rauscher, 119 U.S. at 419. The inquiry into whether a treaty is selfexecuting does not focus on whether a particular term is express or implied but on: “(1) the purposes of the treaty and the objectives of its creators, (2) the existence of domestic procedures and institutions appropriate for direct implementation, (3) the availability and feasibility of alternative enforcement methods, and (4) the immediate and longrange social consequences of self or nonselfexecution.”Islamic Republic of Iran v. Boeing Co., III F.2d 1279,1283 (9th Cir. 1983). For the reasons we have already discussed, we have no doubt that the Treaty and the implicit nokidnapping provision are selfexecuting.

18 In Verdugo's separate trial on narcotics charges, District Court Judge J. Lawrence Irving interviewed the Mexican police officers who were apparently involved in Verdugo's apprehension. The sealed transcript of these interviews suggests the possibility of involvement by high level Mexican officials. The district court should determine in the first instance the evidentiary value of this transcript, if any.

19 The government has chosen not to address our question, relying instead on its argument that there is no treaty violation to remedy.

20 provisions relating to capital punishment and the extradition of nationals expressly grant the requested nation the discretionary power to refuse extradition under appropriate circumstances. The provision relating to political and military offenses, on the other hand, states that extradition “shall not be granted” for such offenses. This provision is “discretionary” in the sense that the requested nation may waive its rights under the Treaty whenever it chooses to do so. See supra at

21 We do not suggest that anything more than an official protest by the offended government to the Executive Branch is required in order to afford standing to a defendant in a criminal proceeding. We merely point out that here the Mexican government did more.

22 Judge Browning contends that we should not decide that Mexico's formal protest confers standing on Verdugo to interpose an objection to the district court's exercise of jurisdiction over him based on the alleged kidnapping. Post at. He would remand to the district court for a determination whether a “formal complaint” addressed to the “judicial authorities” of the United States constitutes a sufficient protest if the formal complaint does not also expressly request the remedy of repatriation. However, the government does not take the position that an express repatriation request is necessary, even though it filed three briefs in our courtHoheitsrechten reprinted in 1985 Neue Zeitschrift fur Strafrecht STZ 464). And even in that decision the statement was dictum, since the note from the Dutch embassy did not meet the German Constitution's requirement that the foreign government formally object to the defendant's prosecution. See post at. In any event, we do not find the German view persuasive and it is, of course, hardly binding on our court. In light of the above, we must reject our colleague's suggestion that we adopt an additional procedural requirement that the government of the United States has not requested and that in this case might retroactively deprive the Mexican government and the individual defendant of their remedy. Finally, we disagree with Judge Browning that the district court should engage in factual hearings regarding the true intent of a foreign government. By contrast with the factual inquiry surrounding the circumstances surrounding Verdugo's abduction, the kind of factfinding involved in the hearing Judge Browning would require comes dangerously close to the inquiries forbidden under the political question doctrine. See supra, part V(C). In any event, such a hearing is unwarranted because the Mexican government's protest should be judged on its face as a matter of law; as such we have held it to be sufficient.

23 Judge Browning cites Eichmann as an example of a case in which personal jurisdiction over a kidnapped individual was deemed proper because the nation from which he was abducted did not expressly demand his repatriation. See post at. In fact, the exercise of jurisdiction over Eichmann was proper because at the time the court conducted its proceedings there was no longer any outstanding protest of any kind by the Argentine government. Although Argentina originally demanded Eichmann's return,subsequently withdrew the entire protest. Israel and Argentina issued a joint communique stating that they had decided to regard the entire incident as closed. See M. Pearlman, The Capture and Trial of Adolph Eichmann 79 (1963) (quoting the communique).

24 Our statement that an offer of return serves to remedy the breach is made for purposes of the issues before us only. Whether additional remedies, voluntary or otherwise, are necessary or appropriate for other purposes affecting the two countries involved is a matter that does not concern us here.

1 Contrary to the majority's suggestion, see supra at note 22, Reporters’ Note 3 of the Restatement is entirely consistent with the Restatement text. Reporters’ Note 3 unambiguously states:Under the prevailing practice … states ordinarily refrain from trying persons illegally brought from another state only if that state demands his return.Restatement (3d) The Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 432 Reporters’ Note 3.

2 For example, in the Bratton case over a century ago, a Canadian national was kidnapped in Canada by Americans and brought to South Carolina for trial. The British government demanded that the charges be dismissed and Bratton be permitted to return to Canada. The United States complied. J.B. Moore, 1 A Treatise on Extradition and Interstate Rendition § 190 at 28384. Similarly, in the Blair case, the United States insisted upon the return of an American citizen kidnaped by Great Britain and the British government complied. Id. § 191 at 285. More recently, inUnited States v. CaroQuintero, 745 F.Supp. 599 (CD. Cal. 1990), the government of Mexico demanded the return of the defendant following his kidnapping by paid agents of the United States, id. at 60304, 608, and the district court ordered his return. Id. at 614. CaroQuintero is currently on appeal before another panel of this court sub nom. United States v. AlvarezMachain, No. 9050459.

3 Contrary to the majority's suggestion, see supra at note 22, the German court's conclusion that a repatriation request is required was not dictum. As the quoted text reveals, the lack of a repatriation request was essential to the court's holding. Nor was the German court's decision based upon the peculiarities of German constitutional law. Article 25 of the German constitution, relied upon by the German court, merely incorporates international law as part of German law. Thus, the German court's decision rests squarely upon the customary practice among nations.

4 The majority defends its bright line rule by suggesting that an inquiry into the actual intent of Mexico “comes dangerously close to the inquiries forbidden under the political question doctrine.” Supra at note 22. The majority fails to explain why presuming, contrary to diplomatic practice, that Mexico's protest was intended as a demand for Verdugo's repatriation, is any less invasive of the executive sphere than determining whether in fact Mexico has demanded Verdugo's return

5 This court does not have a copy of the United States’ response.

6 Mexico's letter of protest was not part of the record below. However, a diplomatic protest is a public document of which we may take judicial notice. See. e.g., United States v. Payton, 918 F.2d 54, 56 (8th Cir. 1990); United States v. Jordan, 913 F.2d 1286, 1287 n.2 (8th Cir. 1990); Fireboard Paper Prod. Corp. v. East Bay Union of Machinists, Local 1304, 344 F.2d 300, 302 n.2 (9th Cir. 1965); Zahn v. Transamerica Corp., 162 F.2d 36, 48 n.20 (3d Cir. 1947);National Labor Relations Board v. E.C. Atkins & Co., 147 F.2d 730, 734 n.1 (7th Cir. 1945)