No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

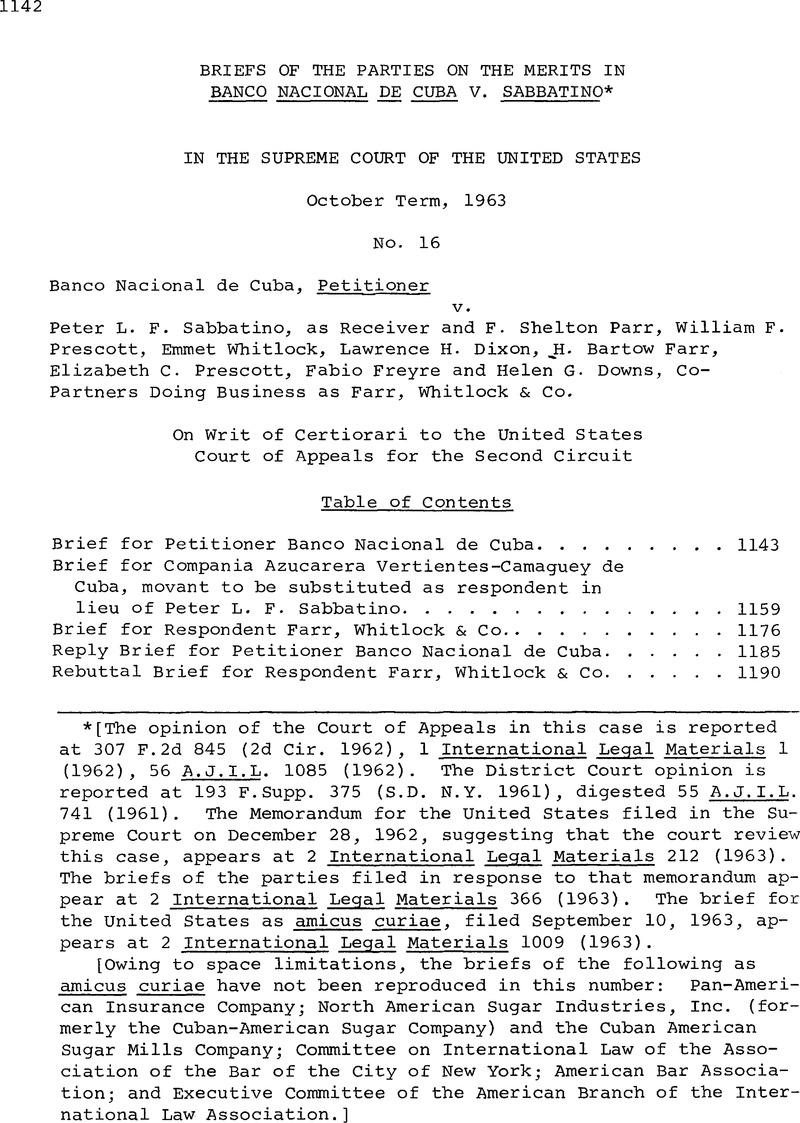

Briefs of the Parties on the Merits in Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1963

Footnotes

[The opinion of the Court of Appeals in this case is reported at 307 F.2d 845 (2d Cir. 1962), 1 International Legal Materials 1 (1962), 56 A.J.I.L. 1085 (1962). The District Court opinion is reported at 193 F.Supp. 375 (S.D. N.Y. 1961), digested 55 A.J.I.L. 741 (1961). The Memorandum for the United States filed in the Supreme Court on December 28, 1962, suggesting that the court review this case, appears at 2 International Legal Materials 212 (1963). The briefs of the parties filed in response to that memorandum appear at 2 International Legal Materials 366 (1963). The brief for the United States as amicus curiae, filed September 10, 1963, appears at 2 International Legal Materials 1009 (1963).

[Owing to space limitations, the briefs of the following as amicus curiae have not been reproduced in this number: Pan-American Insurance Company; North American Sugar Industries, Inc. (formerly the Cuban-American Sugar Company) and the Cuban American Sugar Mills Company; Committee on International Law of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York; American Bar Association; and Executive Committee of the American Branch of the Inter-national Law Association.]

References

* [The brief, dated August 29, 1963, was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on August 31, 1963. The introductory part of the brief has been omitted.]

2 The Indonesian nationalization decrees are significant; they are very similar to the Cuban decrees in language and intent; they might also be termed “discriminatory, retaliatory and without compensation.” For a text of one of the most significant decrees, see The Measures Taken by the Indonesian Government against Nether-lands Enterprises, 5 Netherlands Int’l L. Rev. 227, 230 (1958).

3 The Act of State doctrine did not, of course, originate with Underhill v. Hernandez, supra. The earliest reported case applying the rule is probably Blad v. Bamfield, 3 Swan. 604, 36 E. R. 992 (1674). See also Waters v. Collot, 2 U. S. (2 Dall.), 247 (1793) ; Hudson v. GucStier, 8 U. S. (4 Cranch.) 293 (1808) ; 1 Ops. Att’y Gen. 45 (1794) commenting on Waters v. Collot, supra; Hatch v. Baen, 7 Hun 596 (N. Y. Sup. Ct. 1876) ; Duke of Bruns-wick v. King of Hanover, 6 Beav. 1, 49 E. R. 724 (1844), aff’d 2 H. L. Cas., 1 (1848).

5 Except for Bernstein v. N. V. Nederlandschc-Amcrikaansche, 210 F. 2d 375 (C. A. 2, 19S4). See, infra, p. 25.

6 See, for .example, Zander, The Act of State Doctrine, 53 Am. J. Int’l L. 826 (1959); Fachiri, Recognition of Foreign Laws by Municipal Courts, 12 Brit. Yb, Int’l L. 95, 102-106 (1931); Morgenstern, Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Legislative, Administrative and Judicial Acts Which Are Contrary to Interna-tional Law. 4 Int’l L. Q. 326 (1951).

7 For a full discussion of the reasons for the Act of State doctrine, sec Reeves, Act of State Doctrine and the Rule of Law—A Reply, 54 Am. J. Int’l L. 141 (1960) ; Lipstein, Case and Comment on the Rose Mary, 1956 Camb. L. J. 138; Seidl-Hohenvelden, Extraterritorial Effects of Confiscations and Expropriations, 49 Mich. L. Rev. 851 (1951).

8 A most disturbing additional problem is raised but not answered by the last footnote in the decision of the Court of Appeals (R. 189). It is there suggested that state law might govern this type of situation. If so, we will have not one court but fifty with jurisdiction to decide these difficult and delicate questions. Of course, as has been noted the New York State courts have long accepted the Act of State doctrine, and have indicated an intent to continue 10 apply it in the current Cuban litigation. See pp. 12 and 17, supra.

9 As the Court of Chancery noted in In re Claim of Helbert Wagg & Co. [1956] 1 Ch. 323, 349, this issue was implicit in Rex v. International Trustee for the Protection of Bondholders Aktiengesellschaft [1937] A. C. 500, but was not raised because, the Chancery Court though it was obvious that the Cold Clause Resolution is well within the sovereign power of the United Slates even though it resulted in the “confiscation” of the property of aliens.

10 The memorandum submitted by the Solicitor General is, of course, not officially reported. It does appear in the files of this Court and has been reprinted in full in 1 Am. Soc. Int’l L., Inter-national Legal Materials, 276, 302-305 (1962).

11 An amendment of the Act was required to correct this situation. See First War Powers Act of 1941, 55 Stat. 839, 50 App. U. S. C. §§601-622.

12 The last two cases arose out of a nationalization which, we believe, was not compensated for, was retaliatory and discriminatory against certain aliens—in the French Revolution.

13 According to the record (R. 44) there were about 6,000 stock-holders of the company, and 1,443,921 shares outstanding.

14 This Court has said, concerning the writings of jurists and commentators in the field of international law: “Such works are resorted to, not for the speculations of their author concerning what the law ought to be, but for the trustworthy evidence of what the law really is.” The Paquete Habana, 175 U. S. 677, 700.

15 We do not quite understand what the Court of Appeals means when it says (R. 174) : “International law is derived indeed from the customs and usages of civilized nations, but its concepts are subject to generally accepted principles of morality whether most men live by these principles or not.” As this Court pointed out in The Antelope, there is regrettably a vast difference between the customs and usages of civilized nations and generally accepted principles of morality. But it is the former, not the latter, which constitutes international law.

16 For a sampling see: Books—Domke, International Aspects of European Expropriation Measures (1941) ; Duke University Law School, The Nationalization of British Industries (1951); Einaudi, Bye and Rossi, Nationalization in France and Italy ( 1955) ; Foighcl, Nationalization; A Study in the Protection of Alien Property in International Law (1957); Friedman, Expropriation in International Law (1953) ; Kunz, The Mexican Expropriations (1940); Macmahon and Dittmar, The Mexican Oil Industry Since Expropriation (1942) ; Nishoff, Confiscation in Private International Law (1956) ; Re, Foreign Confiscations in Anglo-American Law (1951); Standard Oil of New jersey, Denials of Justice (1940); U. S. Dep’t of State, Compensation for American-Owned Lands Expropriated in Mexico (1939); G. White, Nationalization of Foreign Property (1961); Wortley, Expropriation in Public International Law (1959).

Articles—Abdel-Wahab, Economic Development Agreements and Nationalization, 30 U. Cine. L. Rev. 418 (1961) ; Allison, Cuba’s Seizure of American Business, 47 A. B. A. J. 48 (1961); Baade, Expropriation of Foreign Private Property and The Decline of the Act of State Doctrine, 1963 J. Bus. L. 182; Becker, Just Compensation in Expropriation Cases: Decline and Partial Recovery, 53 Am. Soc. Int’l Proc. 336 (1959) ; Dawson and Weston, “Prompt, Adequate and Effective”: A Universal Standard of Compensation:’, 30 Fordliam L. Rev. 727 (1962) ; Domke, Foreign Nationalizations: Some Aspects of Contemporary International Law, 55 Am. J. Int’l L. 585 (1961); Domke and Baade, Nationalization of Foreign-Owned Property and the Act of State Doctrine—Two Speeches, 1963 Duke L. J, 281; Drueker, Compensation Treaties Between Communist States: An Addendum, 10 Int’l and Comp. L. Q. (1961) ; Dunham, Griggs v. Allegheny County (82 Sup. Ct. 531) in Perspectivc: Thirty Years of Supreme Court Expropriation Law, 1962 Sup. Ct. Rev. 63; Fachiri, Expropriations and International Law, 1952 Brit. Int’l L. 15; Graving, Shareholder Claims Against Cuba, 48 A. B. A. J. 226 (1962); Katzarov, Validity of the Act of Nationalisation in International Law, 22 Modern L. Rev. 639 (1959) ; Kissam and Leach, Sovereign Expropriation of Property and Abrogation of Concession Contracts, 28 Fordham L. Rev. 177 (1959) ; Kutner, Habeas Proprietatim: An International Remedy for Wrongful Seizures of Property, 38 U. Det. L. J. 419 (1961); Lee, Proposal for the Alleviation of the Effects of Foreign Expropriatory Decrees. Upon International Investments, 36 Can. B. Rev. 351 (1958); Mann, Outlines of a History of Expropriation, 75 L. Q. Rev. 188 (1959); Metzger, Act of State Doctrine and Foreign Relations, 23 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 881 (1962) ; Nugent, Notes on Compensation and Expropriation, 33 Man. B. News 57 (1961); Patty, Tax Aspects of Cuban Expropriations, 16 Tax L. Rev. 415 (1961) ; Re, Foreign Claims Settlement Commission: Its Functions and Jurisdiction, 60 Mich. L. Rev. 1079 (1962); Reeves, Cuban Situation: The Political and Economic Relations of the U. S. and Cuba, 17 Bus. Law 980 (1962) ; Rheinstein and Wortley, Observations on Expropriation, 7 Am. J. Comp. L. 86 (1958) ; Schubert, Compensation Under New German Legislation on Expropriation, 9 Am. J. Comp. L. 84 (1960); Seidl-Hohenveldern, Communist Theories on Confiscation and Expropriation: Critical Comments, 7 Am. J. Comp. L. 541 (1958) ; Timberg, Expropriation Measures and State Trading, 55 Am. Soc. L. Proc. 113 (1961); Todd, Winds of Change and the Law of Expropriation, 39 Can. B. Rev. 542 (1961) ; Wadmond, Judicial Protection of Property Abroad, 16 Bus. Law 688 (1961) ; Williams, International Law and the Property of Aliens, Brit. Yb. Int’I L. 1 (1928); Wortley, Protection of Property Situated Abroad, 39 Tul. L. Rev. 739 (1961).

Notes—Act of State Doctrine—Its Relation to Private and Public International Law, 62 Colum. L. Rev. 1278 (1962); Act of State Doctrine—A New Look, 11 De Paul L. Rev. 76 (1961); “Act of State” v. International Law, 13 Mercer L. Rev. 370 (1962) ; Castro Government in American Courts: Sovereign Immunity and the Act of State Doctrine, 75 Harv. L. Rev. 1607 (1962); Expropriation-Consequential Damages Under the Constitution, 19 La. L. Rev. 491 (1959); Foreign Nationalization Statutory Remedy in New York, 13 Syracuse L. Rev. 555 (1962) ; Foreign Seisure of Investments: Remedies and Protection, 12 Stan. L. Rev. 606 (1960); International Law: A Qualification of the Act of State Doctrine, 4 Ariz. L. Rev. 79 (1962) ; Investment Guaranty Program and the Problem of Expropriation, 26 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 100 (1959).

17 The series of Cuban nationalization laws and decrees have been widely discussed, in general terms, by the voluminous literature on the subject. See, for example, for opposing points of view, on the one hand : Huberman and Sweezy, Anatomy of a Revolution (1960) ; Williams, The United States, Castro and Cuba (1962); Morray, The Second Revolution in Cuba (1962) ; and on the other, Phillips, Cuba; Island of Paradox (1960) and Smith, The United States and Cuba (1960).

The easiest reference in English to the specific nationalization decrees can be found in the files of the New York Times. Zeitlin and Scheer, Cuba: Tragedy in Our Hemisphere (1963) likewise contains much material on the subject. It is clear that nationalization decrees were passed both before and after the August 6 decree which is involved in this case. For example, the Agrarian Reform Act which nationalized most large Cuban landholdings, regardless of owner, was passed on May 17, 1959 (New York Times, May 18, p. 8, col. 3 ; May 19, p. 1, col. 6). Zeitlin and Scheer, op. cit., point out at page 124 that: “In comparison with expropriations of Cubanowned land, . . . seizures of U. S. owned land were meager”. Large amounts of property of Battista supporters, all of them Cubans, were nationalized on December 22, 1959 (New York Times, December 23, p. 1, col. 8). Cubanowned match factories were nationalized on January 4, 1960 (New York Times, January 5, p. 10, col. 4).

Other nationalizations, including Cuban, American, Chinese and Canadian properties, were effectuated as follows: Cuban television and radio stations February 22 and March 26, 1960 (New York Times, February 22., p., col. 1; March 27, p. 30, col. 1); the Cuban molasses industry, February 16, 1960 (New York Times, February 17, p. 12, col. 4); Cuban Telegraph Company, March 1, 1960 (New York Times, March 2, p. 12, col. 4) ; Cuban hotels both American and Cuban owned, June 11, 1960 (New York Times, June 12, p. 1, col. 7) ; United States owned fertilizer plants, July 16, 1960 (New York Times, July 17, p. 19, col. 1; the Cuban Electric and Cuban Telephone Companies, August 7, 1960 (New York Times, August 8, p. 1, col. 6) ; the Chinese (Taiwan) owned bank, September 5, 1960 (New York Times, September 6, p. 18, col. 4) ; United States banks, September 16, 1960 (New York Times, September 17, p. 11, col. 1 ; September 18, p. 39, col. 8) ; the Cuban tobacco industry, September 16, 1960 (New York Times, September 17, p. 11, col. 1) ; Cuban owned banks, sugar mills, distilleries, chemical companies, textile factories, rice mills, department stores, construction industries, shipping companies, etc., October 13, 1960 (New York Times, October 15, p. 1, col. 8); rental housing, October 19, 1960 (New York Times, October 20, p. 9, col. 6) ; Canadian banks, December 8, 1960 (New York Times, December 9, p. 1, col. 2).

18 As a matter of fact, even the immediate result of the decree of August 6, 1960, was less “discriminatory” than might appear. Its effect was to nationalize almost all of the largest Cuban sugar mills. Nine out of the ten largest sugar mills in Cuba and 17 of the 20 largest were nationalized by the August 6 decree. The mills left over for subsequent nationalization represented the smallest sector of the industry. Farr & Co., Manual of Sugar Companies (1958) ; Villarejo, American Investment in Cuba, New University Thought 79, 80, 81 (Spring, 1960).

19 The first nationalizations decreed by the Soviet Union seem to have been on December 14, 1917; other decrees followed from time to time, and nationalization was not completed until 1920. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917-1928, Vol. II at 43, 75. 99, 128, 129 and passim (1952).

20 The Buenos Aires Protocol of Non-intervention of December 23, 1936 (51 Stat. 41, T.S. 923; 188 L.N.T.S. 31) provides as follows :

Article 1. The High Contracting Parties declare inadmissible the intervention of any of them, directly or indirectly, and for whatever reason, in the internal or external affairs of any other of the Parties.

The Charter of the Organization of American States signed at Bogota April 30, 1948 (2 U.S.T. 2395; T.I.A.S. 2361; 119U.N.T.S. 3) provides as follows:

Article 15

No State or group of States has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever, in the internal or external affairs of any other State. The foregoing principle prohibits not only armed force but also any other form of interference or attempted threat against the personalty of the State or against its political, economic and cultural elements.

See also the Pact of Bogota, signed on April 30, 1948, which provides:

Article 1. The High Contracting Parties, solemnly reaffirming their commitments made in earlier international conventions and declarations, as well as in the Charter of the United Nations, agree to refrain from the threat or the use of force, or from any other means of coercion for the settlement of their controversies, and to have recourse at all times to pacigc procedures. I Annals of the Organization of American States, 91 (1949).

21 The New York Times of June 13, 1961, p. 18, col. 1. reported that former President Eisenhower acknowledged that on March 17, 1960, he ordered that governmental assistance be given to the Cuban exiles in the United States. Similarly Richard M. Nixon has said that: “Early in 1960 . . . the CIA was given instructions to pro-vide arms, ammunition, and training for Cubans who had fled the Castro regime and were now in exile in the United States and various Latin American countries.” Nixon, Six Crises at 352 (1962). This confirms a similar date given by Meyer and Szulc, The Cuban Invasion at 53, 54 (1962).

22 Were it not impractical, we would reprint in full the several notes sent by the Mexican Government to the United States on this subject, since they set forth with logic and dignity the position of an underdeveloped country which is seeking to provide a better life for its people and which finds itself unable to make compensation for the property expropriated. The reasoning therein set forth does not, we believe differ materially from the justifications for similar expropriations which have taken place more recently in Indonesia and Brazil and which are currently taking place in Ceylon.

23 We do not suggest that governmental confiscation of property started in 1917. Indeed, the American Colonies during and after the Revolutionary War confiscated Tory property in the Colonies and never made adequate compensation. See Van Tyne, Loyalists and the American Revolution, at 276, 335 (1929).

24 This article contains a great deal of valuable material relating to recent practice in the handling of nationalization claims.

25 A report of the lengthy proceedings leading up to the General Assembly vote can he found in 18 The Record of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York 377 (1963).

26 New York Times, July 6, 1963, p. 3. col. 1; July 7, p. 5, col. 1. The text of the resolution finally adopted was kindly supplied to counsel by Charles S. Rhyne, Esq., Chairman of the Special Committee on World Peace Through Law of the American Bar Association in a letter dated July 29, 1963.

26 Except Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Ltd. V. Jaffrate (The Rose Mary), [1953] 1 Weekly L. R. 246 criticized in In re Claim of Helbert Wagg & Co. Ltd. [1956], 1 Ch. 323, 346.

* This point is well developed in the amicus brief for The Association of the Bar of the City of New York, which also shows that the Cuban actions in question clearly violated international law. The amicus brief for the American Bar Association also deals effectively with the latter point.

* This view is supported by the authorities collected in n. 3 at p. 7 of the Government’s amicus brief and a number of others with which it has seemed unnecessary to burden this Court.

** See also the pertinent authorities collected in Appendix I to the amicus brief for The Association of the Bar of the City of New York. The three European cases which Petitioner has cited at pp. 13-14 of its brief for a contrary view do in fact support the proposition that there is no European act of state doctrine. In Societe Hardmuth, Court of Appeals of Paris (1950), 44 Revue Critique De Droit International Prive 500 (1955), 79 Journal Du Droit International (Clunet) 1200 (1952), the court held that a Czecho-slovakian expropriation had no extraterritorial effect on a nationalized company’s property located in France. The court did hold, how-ever, that the seizure of the company’s trademark and industrial property rights would be recognized and protected in France as rights of the nationalized enterprise. But this holding was expressly based on the Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property Rights of Paris of March 20, 1883 and of the Convention of August 17, 1923.

* [The brief, dated September 30, 1963, was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on September brief has been omitted.] 30, 1963. The introductory part of the brief has been omitted.]

* The doctrine of immunity for acts of state was based on an analogy from the immunity given to the foreign sovereign and his agents and property. Never clearly analyzed in the early cases, the distinction between the two situations was gradually blurred until the same reasons were advanced to justify the two principles.” Zander, The Act of State Doctrine, 53 AM. J. INT’L L. 826, 850-51 (1959).

* Immediately after stating this rule, Mr. Chief Justice Fuller said :

“Nor can the principle be confined to lawful or recognized governments, or to cases where redress can manifestly be had through public channels. The immunity of individuals from suits brought in foreign tribunals for acts done within their own States, in the exercise of governmental authority, whether as civil officers or as military commanders, must necessarily extend to the agents of governments ruling by paramount force as matter of fact.” Id. at 252.

See also the opinion below, 65 Fed. 577 (2d Cir. 1895) at 579, for another reference to “the immunity of public agents from suits brought in foreign tribunals for acts done within their own states in the exercise of the sovereignty thereof.”

* In the Hatch case the court properly noted that in the case of Duke of Brunswick v. King of Hanover, 2 H.L.C. 1 (1848), cited by the Government at p. 14, n. 6 of its amicus brief and by Petitioner at p. 14, n. 3 of its Brief:

“The adjudication was put upon the principle, that no court in England could entertain questions to bring sovereigns to account for acts done in their sovereign capacities abroad.” Id. at p. 600.

Two other cases cited by the Government at p. 14, n. 6 of its brief also dealt primarily with a foreign sovereign’s personal immunity. The Santissima Trinidad and The St. Ander, 20 U.S. (7 Wheat.) 268 (1822) involved the immunities belonging to foreign public ships in our ports, and L’Invincible, 14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 532 (1816) involved the immunity which a sovereign commission confers on a private vessel.

* ” [Because of] the equality and absolute independence of sovereign States, . . . every sovereign becomes the acknowledged arbiter of his own justice, and cannot, consistently with his dignity, stoop to appear at the bar of other nations to defend the acts of his commission agents, much less the justice and legality of those rules of conduct which he prescribes to them.” L’Invincible, supra at 536.

** This case has been criticized as “[p]robably the most extreme and objectionable application of the [act of state] doctrine . . . .” Zander, supra at 832. Furthermore, it did not involve any problem of violation of international law and, in no aspect, can it be regarded as controlling here.

* Even where the sovereign is itself a party defendant, the modern trend, both judicial and executive, has been to limit, rather than to extend, the area of immunity. For example, in the case of Republic of Mexico v. Hoffman, 324 U.S. 30 (1945) this Court refused to recognize the immunity of a vessel owned but not operated by a foreign state. In the “Tate Letter” of 1952, 26 Dep’t State Bull. 984, the Acting Legal Advisor of the Department of State announced that in the future the Department would suggest immunity for a foreign state only with regard to public or governmental acts (jure imperii) and not private or commercial acts (jure gestionis). The immunity of a foreign sovereign has also been limited in those cases in which a sovereign has sued as plaintiff in our courts and has been held to be subject to counterclaims, related or unrelated. See National City Bank v. Republic of China, supra.

** According to Hjerner, The General Approach to Foreign Confiscations, 2 Scandinavian Studies In Law 179, 204 (1958) judicial review of foreign acts of state does not constitute a significant affront to the foreign sovereign.

“The sacrosanctity of foreign acts of state ... is a specifically Anglo-American doctrine having its origin in old English constitutional law and cannot be accepted as a base for a general theory about the effects of foreign confiscations. To this great and complicated question there is only space here to stress the misleading character of the very frequent statements that not to recognize an act of a foreign state would amount to sitting in judgment on acts of the foreign state. Courts outside the foreign country, however, do not rehear the case once it has been decided by the act of the foreign state—they only have to decide whether out of the law they are administering, they want to attribute any effects to the foreign act and, if so, what effects. They cannot reasonably be said to impair the foreign sovereignty thereby and it is difficult to find any settled state practice or rule of international law precluding one state from attributing or not attributing any effects whatever to acts of another state.” (Emphasis in original)

* “Every sovereign State is bound to respect the independence of every other sovereign State, and the courts of one country will not sit in judgment on the acts of the government of another done within its own territory.” 168 U.S. at 252.

** “[The act of state doctrine] is not entirely a matter of comity. Persons who dealt with the former Spanish government are entitled to rely upon the finality and legality of that government’s acts, at least so far as concerns inquiry by the courts of this country.” 114 F.2 d at 444.

* “The conduct of the foreign relations of our Government is committed by the Constitution to the Executive and Legislative— ‘the political’—Departments of the Government, and the propriety of what may be done in the exercise of this political power is not subject to judicial inquiry or decision.” 246 U.S. at 302.

** See Hjerner, supra at 188 discussing generally the confiscation of a right to payment.

* “The case concerns the right to the proceeds from the sale of sugar originally owned in Cuba by a Cuban corporation . . . .” Gov’t Br. p. 4.

* See, e.g., Reeves, Act of State Doctrine and the Rule of Law— A Reply, 54 AM. J. INT’L L. 141, 148 (1960); Banco de Espana v. Federal Reserve Bank, supra.

* The rule for which we contend need not prevent the courts in appropriate cases from affording protection to purchasers in international trade. For example, as the Government concedes, “even if an act of state should be held invalid . . . the applicable property law might still protect the title of a bona fide purchaser.” (Gov’t Br. p. 38)

* In a dissenting opinion in Colegrove v. Green, 328 U.S. 549, 572-73 (1946). Mr. Justice Black recognized the elusive character of the “political” label and the need for judicial protection of certain so-called political rights: “It is true that voting is a part of elections and that elections are ‘political.’ But as this Court said in Nixon v. Herndon, [273 U.S. 536] ... it is a mere ‘play upon words’ to refer to a controversy such as this as ‘political’ in the sense that courts have nothing to do with protecting and vindicating the right of a voter to cast an effective ballot.”

* Rich v. Naviera Vacuba, S.A., 197 F. Supp. 710 (E.D. Va.), aff’d, 295 F.2d 24 (4th Cir. 1961), cited by Petitioner, is a sovereign immunity case. There the Government had filed a certificate of immunity with respect to the vessel (The Bahia de Nipe) and its cargo, both owned by the Cuban Government. In addition to the principle of sovereign immunity, which alone was dispositive, support for the court’s conclusion as a matter of urgent national interest may also be found in circumstances set forth in detail in the Government’s Memorandum in Opposition to the Application for a Stay in that case. Shortly before the defection of the Bahia de Nipe crew, the United States and Cuba had informally agreed to return any property “hi-jacked” from the other. On the day before the Bahia incident, Cuba had complied with the agreement by returning a hijacked American airliner, so that the court was indeed compelled by urgent considerations to dismiss the libels as it did.

** We disagree with the view of the Government’s amicus brief which seems to treat the Executive as the only branch of government competent to identify principles of international law and cases of their violation. Cf. Gov’t Br. p. 30:

“The short of it is that it is essential, from the standpoint of conducting foreign relations, that the position to be taken by the United States regarding the legality of the acts of a foreign government within its jurisdiction should be determined by the Executive, not by individual state and federal judges.”

* “International law is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction, as often as questions of right depending upon it are duly presented for their determination.” The Paquete Habana, supra at 700.

* For a concise refutation of this argument, see Note, The Castro Government in American Courts: Sovereign Immunity and the Act of State Doctrine, 75 HARV. L. REV. 1607, 1617-18 (1962).

** It may be noted in passing that this second consideration pointed to by the Government appears somewhat inconsistent with its first consideration; for if disruptive effects would result from a non-application of the act of state doctrine in our courts, any such disruption would be de minimis since, if the Government’s first point is valid, such cases will occur in the United States only sporadically.

* See, e.g., letters of President Kennedy to the President of the Asian and Australasian Conference on World Peace Through Law, dated September 1, 1961, the President of the African and Middle Eastern Conference on World Peace Through Law, dated December 2, 1961, the President of the American Conference on World Peace Through Law, dated June 7, 1961, the President of the European Conference on World Peace Through Law, dated April 2, 1962, and the President of the First World Conference on World Peace Through Law, dated June 20, 1963. In his letter of December 2, 1961, the President stated, in part:

“We have seen the successful operation of international law in established areas like the Law of the Sea. But the uncharted seas of arms control and the peaceful use of outer space demand the development of new rules of law. The tremendous strides in science and technology lend urgency to the need for these new rules and for legal institutions capable of harnessing the wonders we have created for the benefit—not the destruction—of mankind.

Supremacy of law within nations insures the freedom of man. Supremacy of law in the community of nations can free mankind from the dread of nuclear war. The rule of law must replace rule by force if we are to look forward to a stable world—a world which is hospitable to economic and social progress.”

Copies of the above letters were furnished by Charles S. Rhyne, Esq., Chairman of the Special Committee on World Peace Through Law of the American Bar Association.

* The Government points out, at page 33 of its brief, that because of the adoption of the Cuban Assets Control Regulations, a judgment for Petitioner would not result in turning over to the Castro regime the proceeds at issue, which would be added to the general fund of assets of Cuban nationals frozen pursuant to such regulations. The Government continues: “[e]ffective negotiations with Cuba to achieve some compensation for all American property which has been nationalized may well prove possible in the course of time.” The significance of these comments is not entirely clear. If intended simply as a reassurance that a decision for Petitioner would not result in delivery of the funds to Cuba at this time, this is irrelevant to the determination of the rival claims of right. If, on the other hand, it is intended to suggest that assets which upon judicial scrutiny might be found to belong entirely to C.A.V. should instead be made available without scrutiny so as to provide a negotiating lever in seeking “some compensation for all [nationalized] American property,” surely such a suggestion cannot be seriously entertained: it would amount to the sanctioning of a deprivation of property without due process. Cf. Home Ins. Co. v. Dick, 281 U.S. 397, 408 (1930).

* The Court of Appeals regarded certain correspondence from representatives of the State Department, submitted to it prior to decision by amicus curiae, as inviting decision by the court and satisfying any requirement of waiver by the State Department (R. 170). The Government attacks the correspondence as not representing the official view of the State Department (Gov’t Br. p. 42), and Petitioner attacks the Court of Appeals for denying it due process by considering the correspondence (Pet. Br. p. 52). Both positions seem to be rather exaggerated. The correspondence certainly went beyond mere amenities and, in view of the high positions occupied by the writers, might reasonably be regarded by a court as not reflecting any deep concern by the Department if the court were to agree with it that the actions of the Cuban Government violated international law. The court’s consideration of the correspondence could hardly have violated any fundamental rights of the Petitioner, since it is hard to sec how, if the Petitioner had had copies of the correspondence in advance, it could have persuaded the State Department either to recant its previous objection to the Cuban action as in violation of international law or, as the Department refused to do, to “comment on matters pending before the courts” (R. 170). Use by appellate courts of some matters dehors the record, even outside the usual fields of judicial notice, has apparently been considered consistent with due process and proper procedure, at least since the so-called “Brandeis” type of brief came into fashion.

However the correspondence may be viewed, it should not be dispositive, if we are correct in our argument that the judiciary is not required to abdicate in favor of the Executive where a violation of international law is shown. There was certainly no occasion for abdication here. Cf. Menendez Rodriguez v. Pan American Life Ins. Co.. supra at p. 437. Furthermore, the Executive had taken no action indicating that it desired the court to abdicate. Whether the correspondence is taken as official encouragement not to abdicate or whether it is disregarded and official silence is thought to be the posture of affairs, there was nothing to suggest that the Executive thought it should have a monopoly in passing on questions of violation of international law as a matter of urgent national necessity in this particular case. We have already argued that it should not have such a monopoly either under the Constitution or on any other basis—unless, perhaps, m some particular case, on grounds of urgent national necessity, established to the. satisfaction of the courts, the Executive affirmatively asks the courts not to act. See The Association of The Bar of The City of New York, Commit-tee on International Law, Report, supra at 11. It will be time enough to consider whether an exception should be made in such a case when it arises. No such situation is presented here.

* “Plainly this was the action, in Mexico, of the legitimate Mexican government when dealing with a Mexican citizen, and, as we have seen, for the soundest reasons, and upon repeated decisions of this court such action is not subject to reexamination and modification by the courts of this country.” (Emphasis added) 246 U.S. at 303. It is in this context that one must read the otherwise gratuitous statement of the Court in that case that it was not necessary to consider the validity of the levy under applicable rules of international law.

* See, e.g., Jessup, A Modern Law Of Nations, 157 et seq. (1952); Briggs, The Law Of Nations 957 (2d ed. 1953) ; Kunz, Sanctions in International Law, 54 Am. J. Int’l L. 324 (i960). The following arc examples of the accelerating development of international institutions and agreements involving acceptance of restrictions on sovereignty with a view toward achievement of common goals.

(1) World Organisation—United Nations. See United Nations Charter, Chapter I (Purposes and Principles), Chapter VI (Pacific Settlement of Disputes), Chapters IX and X (International Economic and Social Cooperation, the Economic and Social Council), Chapters III and XIV (International Court of Justice)

(a) The Economic and Social has established various Commissions, such as the So Commission, the Commission on Human Rights and the Commission on International Commodity Trade, to it in its functions. Also, a variety of standing committees, such as the Technical Assistance Committee, the Committee for Industrial Development and the Committee on Negotiations with Inter-Governmental Agencies, and several special bodies, such as the United Nations Children’s Fund, function under its aegis. In addition, Regional Economic Com-missions operate within this framework, e.g., Europe (ECE), Asia and the Far East (ECFAE), Latin America (ECLA), and Africa (ECA).

(b) Much of the work of improving world economic and social conditions is carried out by so-called “Specialized Agencies,” established by inter-governmental agreement and associated with the United Nations under Article 57 of its Charter, such as: International Atomic Energy Agency; International Labour Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; World Health Organization; International Monetary Fund; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; International Development Association (Bank affiliate) ; International Finance Corporation (Bank affiliate); International Civil Aviation Organization; Universal Postal Union; International Telecommunication Union; World Meteorological Organization ; Intergovernmental Maritime Consultative Organization and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

(c) Many ad hoc bodies, such as the International Law Commission, the Disarmament Commission and the Com-mission on Conciliation for the Congo, are appointed from time to time by the General Assembly.

(2) International Communities—

(a) European Community—(European Coal and Steel Community; European Economic Community; European Atomic Energy Community). These communities also have an Assembly and Court of Justice and other subsidiary organizations. See UNTS, Vol. 261, No. 3729, p. 140; UNTS, Vol. 298, No. 4300, p. 11; ibid., No. 4302, p. 267; ibid., No. 4301, p. 167. The Common Market was established under the European Economic Community Treaty, UNTS, Vol. 298, No. 4300. There is also the Council of Europe and the Organization for European Economic Cooperation.

(b) Organization of American States, see UNTS, Vol. 119, p. 3. In addition, a Latin American Free Trade Area was provided for under the Treaty of Montevideo (1960), and a Central American Common Market was established in the Treaty of Economic Association (1960). As yet, these customs unions are not fully operative.

(3) Other Inter-Governmental and Non-Governmental Bodies—The multiplicity of inter-governmental and non-governmental institutions is limited only by the number of specialized problems encountered among nations. See listing of approximately 140 inter-governmental organizations and 1,500 non-governmental bodies in Year Book Of International Organizations (9th ed. 1962-63).

(4) Treaties and Agreements—A study by the Secretariat of the United Nations, The Status of Permanent Sovereignty Over Natural Wealth and Resources, U.N. Doc. No. A/AC.97/5 Rev. 2 (1962) (hereinafter “U.N. Publication”) contains a list of over 100 treaties of friendship and commerce and agreements relating to ownership and exploitation of natural resources. See U.N. Publication at 71-72, 228-30.

(5) International Conferences and Conventions—Government sponsored international conferences on a variety of topics, such as the 1958 Geneva Conference on the Law of the Sea, or those sponsored by private international associations or groups, such as the 1963 Athens Conference on World Peace Through Law, have been held with increasing frequency.

For an historical development of the changing international scene from the period following the First World War, see Friedman, Expropriation In International Law 17 et seq. (1953); Wortley, Expropriation In Public International Law 61 et seq. (1959).

* See authorities collected in Appendix II hereto.

* “Every act of the Guatemalan Government constitutes a sovereign act, as do the acts of every other sovereign Government, including the acts of the Government of the United States. But to state that no sovereign act of a Government [a]ffecting foreign states or their nationals is open to discussion, or question, as to its validity under international law, because it is a sovereign act, is to say that states are not subject to international law. . . . “The obligation of a state imposed by international law to pay just or fair compensation at the time of taking of property of foreigners cannot be abrogated from the international standpoint by local legislation.” 29 Dep’t State Bull. 358, 360 (1953).

* Drucker, Compensation Treaties between Communist States, 10 INT’L & COMP. L.Q. 238, 248-50 (1961) points out:

“By recognising among themselves the principles of territoriality, and of the obligation to pay compensation for nationalisation, Communist States have come into line with the traditional rules of international law. ... It has been shown that these doubts concerning the duty to pay compensation, which is alleged to arise from the practice of Socialist States—even if it is assumed that this practice has the effect Prof. Hans W. Baade 154 Am. J. Int’l L. 801 (1960)] appears to ascribe to it— are contradicted by the practice of Socialist States between themselves.”

* See also Egypt’s recognition of the duty to pay compensation in regard to the Suez Canal, Law of July 26, 1956; Declaration of April 24, 1957, 51 AM. J. INT’L L. 673, 675 (1957); Agreement of April 29, 1958, 54 AM. J. INT’L L. 493 (1960), and Iran’s agreement to compensate, Nationalization Law of May 1, 1951, Arts. 2, 3; Agreement of September, 1954, see Farmanfarma, The Oil Agreement Between Iran and the International Oil Consortium: the Law Controlling, 34 TEXAS L. REV. 259, 261 (1955).

* Failure to reach this degree of unanimity at the 1963 Conference on World Peace Through Law in Athens seemed due to a feeling on the part of some delegates that attempts were being made to push through resolutions on nationalization without sufficient consideration. Those who attended would undoubtedly corroborate that postponement for further study did not result from widespread differences on the propriety of compensation. See N.Y. Times, July 6, 1963, p. 3, col. 1.

Significantly, the Athens Conference adopted a “Declaration of General Principles” several of the provisions of which are pertinent here as reflecting the consensus for dedication to the continuing development of the rule of law among nations:

“1. All states and persons must accept the rule of law in the world community. In international matters, individuals, juridicial persons, states and international organizations must all be subject to international law, deriving rights and incurring obligations thereunder.

2. The rule of law in international affairs is based upon the principle of equality before the law. . . .

3. International law and legal institutions must be capable of expansion, development or change to meet the needs of a changing world composed of nations whose interdependence is ever on the increase and to permit progress in political, social and economic justice for all peoples. . . .

4. Those who are subject to international law must resolve their international disputes by adjudication, arbitration, or other peaceful procedures. . . .” 49 A.B.AJ. 858-59 (1963).

* As Petitioner recognizes (Br. p. 41), reasonable conditions generally applied may be imposed for example on aliens’ freedom to travel or to practice certain professions; but an act which affects only a particular group of aliens is clearly invalid. See 62 COLUM. L. REV. at 1301-02.

** Even in writings from Communist countries, such discriminatory measures of nationalization have been condemned as unlawful. See Domke, Foreign Nationalisations, 55 AM. J. INT’L L. 585, 603 (1961).

* See note at p. 33 supra.

* The peace treaties after both World Wars adopted the control theory and the decisions of arbitral tribunals thereunder applied the test. See RABEL, op. cit. supra at 57-59. The control test also was applied by the Permanent Court of International Justice in Certain German Interests in Polish Upper Silesia, P.C.I.J., ser. A, No. 7, 68-69 (1926).

* FRIEDMAN, op. cit. supra at 171, states:

“International law only takes account of the real nationality of the physical persons covered by the legal fiction of corporate personality, since such physical persons alone possess any importance as nationals of a State. As Professor Borchard rightly points out: ‘the company is simply a form of organisation, a veritable cloak, which allows individuals to enjoy their property, and an injury inflicted upon this form as such is a pure fiction. It is the individuals who derive an advantage from the organisation constituted in the form of a company and who are injured. . . .’ In other words, international law deliberately sacrifices the unitary conception of legal personality which regards corporations as having a single nationality in order to look beyond the legal forms and to determine the interests and the parties actually suffering injury.” (Footnotes omitted)

** Schwarzenberger, op. cit. supra at 175-76, states:

“There is not one single test which has been accepted by State practice for all purposes.”

* Vladikavkazsky ry. V. New york trust Co., 263 N.Y. 369, 379, 189 N.E. 456, 460 (1934) distinguishes the opinion in M. Salimoff & Co. v. Standard Oil Co., 262 N.Y. 220, 186 N.E. 678 (1933), cited by both Petitioner and the Government, pointing out that the “general statement” contained therein to the effect that recognition retroactively validates all of the acts of the particular government “must be read in connection with its context and as so read it did not refer to acts sought to be given effect extraterritorially.” Id. at 379. The “general statement” in the Salimoff case, quoted on page 12 of Petitioner’s brief:

“The courts of one independent government will not sit in judgment upon the validity of the acts of another done within its own territory, even when such government seizes and sells the property of an American citizen within its boundaries “was pure dictum—the owners of the property there involved, which had been seized by the Russian government, were Russian nationals.

* See the discussion at pp. 20-21, supra.

** The fact that Farr subsequently entered into a new contract is beside the point. However “fortuitously”, the proceeds of sale are here in New York, and C.A.V.’s right thereto is independent of any action by Farr. In fact, however, the record could not be clearer that Farr in this case did not “freely” contract with C.A.V.’s financial agent, but was compelled to do so in order to clear the ship for departure from the Cuban area and thus meet its commitments for resale of the cargo to its customer in Morocco (R. 75, 133). When Farr was confronted with the rival claims of C.A.V. and Petitioner to the proceeds in New York, it acted as any “stakeholder” would (as well as pursuant to court order) in refusing to turn them over pending clarification by the courts (R. 26, 49-50). Cuba then invoked the process of the court to effectuate its taking.

* At least one decision of this Court also appears to support the proposition that foreign acts repugnant to national “public policy” will not be given effect. In Oscanyan v. Arms Co., 103 U.S. 261 (1880) this court refused to give effect to a Turkish law according to which the plaintiff, a Turkish consular official, was allegedly allowed to enter into an agreement with a private company to obtain a commission for the sale of arms. This Court found such action to be “so repugnant to all our notions of right and morality, that it can have no countenance in the courts of the United States.” Id. at 278.

** “In any case in which the President determines that a nation . . . [has] nationalized, expropriated, or otherwise seized the owner-ship or control of the property of United States citizens . . . and has failed within six months following the taking of action ... to discharge its obligations under international law toward such citizens, including the prompt payment to the owner or owners of such property so nationalized, expropriated, or otherwise seized, ... the President shall suspend any quota ... to purchase and import sugar under this chapter of such nation until he is satisfied that appropriate steps are being taken.” 7 U.S.C. § 1158(c) as amended July 13, 1962, 76 Stat. 166.

Also, Section 620(e) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended by Section 301 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1962, provides:

“The President shall suspend assistance to the government of any country . . . when the government of such country . .. has nationalized or expropriated or seized ownership or control of property owned by any United States citizen or . . . corporation . . . and . .. fails within a reasonable time ... to take appropriate steps, ... to discharge its obligations under international law toward such citizen or entity, including equitable and speedy compensation for such property in convertible foreign exchange, as required by international law . . . .” 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e), as amended 76 Stat. 260.

* Along with the Kane case, Petitioner at p. 13 of its brief also cites Theye Y Ajuria v. Pan American Life Ins. Co., 154 So. 2d 450 (La. Ct. App. 1963), as a case applying the act of state doctrine to a Cuban nationalization of property owned by United States nationals. In fact, however, the court in Theye viewed the fact that the Cuban act there in question affected plaintiff, a Cuban national, as dispositive when it said:

“It is a well established principle of law, recognized by all appellate court decisions, that a recognized Sovereign Nation can make laws binding upon its nationals within its bounds.” Id. at 452.

* Petitioner’s contention in Point VI of its brief (that even if the taking violated international law CA.V.’s only remedy is for damages in an international forum) would seem to be irrelevant here. This Court need not determine the proper form of action for C.A.V. if it brought an action or the validity of a setoff or counter-claim if this case were reversed and remanded.

This is a case in which Petitioner, not C.A.V., is seeking a remedy; the proceeds are not in Petitioner’s hands and hence “restitution” is not involved. But in any event, it is clear that under international law restitution is a proper remedy for an illegal taking. See, e.g., Chorzow Factory, supra at 4, 47-48 (dictum) ; Portuguese Religious Properties Case (France, Great Britain and Spain v. Portugal), 1 U.N. Rep. Int’l Arb. Awards 7 (Perm. Ct. Arb. 1920), SCOTT, HAGUE COUBT REPORTS 1, 5 (1932); 2 WHITE-MAN, DAMAGES IN INTERNATIONAL LAW 857 (1937). Finally, in this case, involving solely the proceeds of sale of the sugar, “damages” and “restitution” appear to be identical.

However, if this Court should reject all of our previous contentions and remand the case to the District Court, that Court would then have to deal with our final contention, that C.A.V. should be afforded the opportunity to protect its position by all proper means, including the interposition of a counterclaim for damages resulting from the confiscation of its assets. The propriety of such a claim, whether considered to be for damages or “restitution”, would appear to be for that Court to determine.

* Cf. the authorities collected in n.16 at p. 21 of the Government’s amicus brief in which the Government lists numerous cases in support of the proposition that “other countries also [recognize] the act of state principle” and then concludes by conceding that civil law countries “reserve the right to refuse to give effect to acts repugnant to the policy of the forum.”

* Petitioner’s brief distinguishes the case because the tobacco in question was in Holland at the time of the nationalization. It is true that plaintiff sought to obtain an order to the effect that ware-house warrants representing tobacco located in Holland should be handed over. But the claim was based on the theory that tobacco located in Indonesia and seized there had been sold by the Indonesian administration. Since the nationalization was not recognized, the sale freed petitioner of a debt for which both quantities of tobacco were under lien, and he was therefore entitled to claim the warrants. Thus, the court had to address itself to the question of the validity of the confiscation of the tobacco located in Indonesia.

* Although this argument was not made in the courts below it is available here in support of the judgment. McGoldrick v. Compagnie Generate, 309 U. S. 430, 434.

* Emphasis in original.

* [The brief, dated September 30, 1963, was filed in the U.S. Supreme court on October 2, 1963. The introductory part of the brief has been omitted.]

* Conflict of Laws (7th ed. 1958) 159.

* 1 Oppenheim, International Law (8th [Lauterpacht] ed.) 327-330.

** It is true that this Court has somewhat narrowed the opinion in Wisconsin as it relates both to judgments and to the duty to each other of the respective states of the United States under the Constitution, Milwaukee County v. White Co., 296 IT. S. 268. But neither judgments nor the reciprocal obligations of states under the Constitution are involved here.

* Emphasis in original.

* Emphasis in original.

* Emphasis in original.

* Emphasis in original.

1 The motion by C.A.V. to be substituted, made at the last Term of this Court, was consolidated with the argument on the merits. C.A.V. has separately briefed that motion, and we shall answer in a separate brief which is being filed simultaneously herewith.

* [The brief, dated October 16, 1963, was filed in the U.S Supreme Court on October 17, 1963. The table of contents has been omitted.]

2 Respondent’s reference to Dicey (Resp.’s Br., pp. 19, 20) is disingenuous. The passage quoted has no relevance to the issue in this case. For the usual rule of conflicts, applying lex situs to determine title to personal property, see Dicey, Conflict of Laws (7th ed. 1958), Rules 86, 87 and 88, pp. 537-544. Application of that rule favors petitioner’s position.

3 Several of the amici curiae makes similar argument. See, for example, the brief of North American Sugar Industries, Inc. at pp. 22-26, and the brief of the International Law Association, at pp. 52-56.

4 See C.A.V. brief, p. 36; Bar Association of the City of New York brief, p. 35; American Bar Ass’n brief, p. 14.

5 Although not fully reported in the United States, all of the foregoing was summarized in a note to the United Nations submitted by the Cuban Government on July 24, 1963. The unpublished note is presumably available from the State Department. See, for some details; Official Records of General Assembly, 15th Sess., 872nd plenary meeting (9/26/60 Castro speech), Official Records of General Assembly, 16th Sess., 1032nd plenary meeting (10/10/61 Roa speech), Official Records of General Assembly, 17th Sess., 1145th plenary meeting (10/8/62 Dorticos speech), Official Records of Security Council, 15th year, 874th meeting (7/18/60 address by head of Cuban Mission). The television interview referred to was printed in full in I. F. Stone’s Bi-Weekly, Vol. XI, No. 12, May 27, 1963, at p. 5.

1 As noted in Farr, Whitlock’s Brief, page 13, and petitioner’s Reply Brief, page 1, the question of comity has not previously been raised. Counsel for Farr, Whitlock therefore did not have petitioner’s views on comity until the Reply Brief was received on October 17.

2 Senate Com. on Foreign Relations, 1st Sees., Events in United States-Cuban Relations, 14, 18, 20, 21 (Com. Print, 1963).

* [The brief, dated October 22, 1963, was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on October 22, 1963.]

3 49 Dept. of State Bulletin, 160. Indeed the Appendix to the Brief of the United States takes the trouble to point out that even if Cuba wins this case it will not get the money.

4 The danger of permitting appearances by private counsel only is illustrated by Rich v. Naviera Vacuba, 197 F. Supp. 710 (D. Va.). In this case Cuba succeeded in repudiating a most formal stipulation entered into by duly authorized private counsel waiving sovereign immunity respecting execution of a judgment for $500,000. Pages 720-23.

5 The thesis that foreign sovereigns with whom the United States does not have diplomatic relations should not be permitted to sue in our courts is persuasively maintained by Mr. J. Gordon Hansen in an article to be published in the January, 1964 issue of the University of Pennsylvania Law Review entitled “The Standing of Foreign Governments to Sue in American Courts”. Mr. Hansen kindly made the manscript of this article available to us. Inter alia Mr. Hansen will say that the courts have not “considered the problem involved in a suit by a recognized government with which the United States does not carry on amicable relations”. Thus the question is at least an open one.