Introduction

Rural women are the pillars of their families and communities as caregivers, farmers, and traders and are key to food security and poverty alleviation. However, they also face challenges that limit their capacity; with the poverty rate in rural Zambia at 76 percent, women are disproportionately affected by the lack of access to resources, education, and health care and income-generating activities.Footnote 1 Various approaches have been considered to empower rural women, but perhaps a practical and feasible route is through cultural production. The opportunities to uplift rural women may well lie within the skills readily available to them such as craft making. These arts and crafts, known as traditional cultural expressions (TCEs), are tangible and intangible forms of creative expression of Indigenous/traditional local communities.

As women are usually involved in craft making as an expression of their cultural identity and heritage, cultural expressions are influenced by gender norms, which reflect the lived realities of the women that craft them. When women sell arts and crafts as souvenirs inspired by their culture, they not only earn incomes to sustain their livelihoods and improve their socioeconomic status but also share their cultural heritage. There have been suggestions on how rural women in Zambia can get better returns for their crafts by developing some form of identification to indicate the origin and name of the community that produces them.Footnote 2 This suggestion envisages a kind of branding. The cultural, social, and economic importance of TCEs make them vulnerable to misappropriation, and measures have been considered to protect them, including intellectual property (IP) rights. These exclusive rights that are granted to inventors and creators are aimed to encourage them to share their innovations and creations with society.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states in Article 31(1) that Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions and the right to maintain, control, and protect their intellectual property over such heritage.Footnote 3 This statement implies using legal mechanisms, including IP rights to protect TCEs. Global debates revolve around the viability of the IP system to protect, promote, and value creative outputs of Indigenous communities. The issue becomes complicated when a gender dimension is infused. A gender bias has been observed in the IP system,Footnote 4 and the conceptions of intellectual activity within the context of IP relegate creations that emerge from Indigenous communities, usually works produced by women. This article considers the intersection of gender, TCEs, collaborative innovation, and IP in the Tonga Indigenous community of Zambia.

The Tonga women weave baskets in craft clubs, which are informal groupings of women who have organized themselves to collaborate in weaving baskets. As a women’s craft, the continuation of the cultural practice preserves this heritage and offers an opportunity for the women to generate an income from selling the baskets. They are bought in and around Zambia and are also popular on online markets. But given that basket weaving is a characteristic of many African countriesFootnote 5 as well as the ever-increasing complexity of the global craft market,Footnote 6 incidences of imitation, copying, and appropriation remain an ever-present trepidation.

This article is divided into five sections, including this introduction. The second section discusses the research methodology. The third section provides the research context. It discusses the Tonga women crafters and the role of the Choma Museum and Craft Centre in preserving the cultural heritage, and facilitating the empowerment, of the rural women. It then examines the gender dimension in IP and TCE protection and the provisions on TCE protection in Zambia’s Traditional Knowledge, Genetic Resources and Expression of Folklore Act (Traditional Knowledge Act).Footnote 7 The fourth section discusses the findings of the study as they relate to open collaborative innovation, TCEs, and IP protection for the Tonga baskets and empowerment of the women through selling the baskets. The fifth section concludes the article.

Methodology

The study employed a qualitative research method to understand the social and cultural context of the Tonga, how gender relations affect women’s creative process, how they openly collaborate in weaving the baskets, and the IP dimensions in protecting the baskets. The study was constituted by desk research with reference to international treaties, Zambian legislation and government documents, research reports, journal articles, and scholarly texts. The desk research was complemented by a field study that involved focus groups with Tonga women to gather gender disaggregate data. Ethical clearance to conduct the field study was granted by the University of Cape Town Faculty of Law Research Ethics Committee.

Three criteria informed the selection of participants: experience in basket weaving, having family/dependents, and membership in a craft club. Data collection methods included documentation, direct observation, and a semi-structured questionnaire administered within a focus group setting. Focus group discussions were conducted via videoconferencing as the women gathered in specific locations to weave baskets since the COVID-19 pandemic made travel impossible. The focus groups provided an opportunity to better understand the knowledge sharing and collaboration within the craft clubs, inspiration behind the designs, and the patterns of the baskets and their cultural significance. The data collected was hand coded to generate themes and categories that are the main findings of this study. Relevant literature and the primary data collected in the focus groups were analyzed to interpret and understand the results of the study. A gender analysis also provided a better understanding of the link between basket weaving and empowerment and how gender influences the open collaborative innovation of the basket weavers.

The women that participated in the focus groups were from areas in the Southern Province of Zambia: Madyongo, Munyumbwe, Siabaswi, Siampondo, Siansalama, and Sinazeze. A total of 70 women who ranged in age from 23 years to 75 years took part in the study, with each focus group’s discussion including about 11 women.

Research context

Tonga women crafters

The Tonga are found in the southern part of Zambia near the Zambezi River. A community embedded in its culture, the Tonga are communal with a deep connection to their heritage and natural environment.Footnote 8 There are defined gender roles – the men raise livestock, and the women tend to the household, grow vegetables, and raise chickens for household consumption. The community relies on subsistence farming and livestock rearing. They grow millet, sorghum, groundnuts, cotton, and beans, but the area has poor soil and little rainfall, so farming is not dependable.Footnote 9 The women buy fish from fishermen to resell, and they engage in growing vegetables along small streams.Footnote 10 The Tonga engage in other activities like pottery, basketry, beadworks, and wood carving to supplement their income. These activities draw upon the traditions of the TongaFootnote 11 and generally are allocated to either men or women.Footnote 12

The women weave baskets, by hand, with different designs and patterns that tell the stories of the women, their cultural history, and the nature that surrounds them.Footnote 13 The weaving techniques involve using different color dyes, which are usually made from vegetables, and the baskets are crafted from different materials; malala palm tree, reeds, and bamboo. The baskets hold a special place in Tonga culture where they are given to girls when they get married. They generally serve a utility function and are used for winnowing, storing harvested grains, and serving dry foods. The women weave the baskets in craft clubs, and, in this environment, open collaborative innovation is central to their craft as they share ideas, patterns, and materials drawing on traditional knowledge in weaving their baskets.

For many Tonga women, the baskets not only represent their culture and serve a useful role in their daily lives, but they are also sold to supplement their incomes. Tonga baskets have been sold in different parts of the world, and they are popular on online markets.Footnote 14 Basket weaving is therefore a form of self-employment, since, without completing formal education, it is difficult for the women to secure formal employment.Footnote 15 Studies observe that, particularly among marginalized women in Indigenous communities, activities such as arts and crafts help women to gain financial independenceFootnote 16 and increase their freedom.Footnote 17 Selling arts and crafts can be a way to alleviate poverty,Footnote 18 and the Tonga women have improved their living conditions through selling these baskets.

Scholars highlight that such women-only environments facilitate autonomy and empowermentFootnote 19 and that environments within which the sharing of knowledge, skills, and daily life experiences occurs – such as craft clubs – allows for the formation of supportive social networks.Footnote 20 Craft making yields social benefits, and it enhances a sense of community and creates support networks for women.Footnote 21 The same is true for the Tonga women. Basket weaving is intricately linked to their way of life. While they craft, the women discuss and share problems and educate the younger women on married life and family, thus developing a social support system.

Craft making also enhances women’s sense of self and is a space to impart generational knowledge and skills.Footnote 22 Within the Tonga community weaving is a practice passed from generation to generation – grandmothers, mothers, aunts – in one family, there can be generations of baskets weavers. There is also a sense of pride in preserving and maintaining cultural heritage since the older women teach the younger ones about the beauty of this generational practice.Footnote 23

Museums and women empowerment

To the extent that cultural production can improve the socioeconomic lives of women, it is empowering. Scholars note that the marketing of cultural products can be a valuable source of income for Indigenous communitiesFootnote 24 – for example, the Maasai women sell their beadwork and other cultural expressions as souvenirs.Footnote 25 Scholars have identified elements of what constitutes empowerment,Footnote 26 and, though definitions vary, it is a process to improve the status of women as they recognize their self-worth and take control of their own lives and participate in political, social, and economic life.

The Zambian government has made efforts to empower women in line with the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goal 5, which seeks to achieve gender equality and empower women and girls. Zambia is signatory to several international and regional instruments showing a commitment to gender equality – the 1979 UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the African Union (AU) Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, and the Southern Africa Development Community’s (SADC) Protocol on Gender and Development.Footnote 27 In 2015, it enacted the Gender Equity and Equality Act to domesticate its international obligations on gender equality and women’s rights.Footnote 28 In implementing its commitments, the government has also adopted initiatives focused on rural women specifically through programs undertaken by the Department of Community Development and the Department of Social Welfare,Footnote 29 as women constitute a significant portion of the rural population of the country, approximately 64 percent.Footnote 30

Some of the government’s women empowerment efforts have been made through the promotion of cultural heritage as, generally, women tend to be involved in craft making due to cultural gender norms.Footnote 31 As institutions for the preservation of cultural heritage, museums have evolved to become enablers of community developmentFootnote 32 and agents of women empowerment. Museums and cultural heritage centers can be focal points in empowerment and effective when considering communities that are embedded in their culture.Footnote 33

The National Museums Board of Zambia has established museums dedicated to specific ethnic groups, including the Choma Museum and Crafts Centre, which has been a key supporter of Tonga women’s crafts.Footnote 34 An ethnographic museum established in 1988, it is dedicated to the preservation of the heritage of the Tonga people and hosts a vast collection of historical and cultural artifacts of the Tonga people. A place of cultural immersion, it exhibits the arts and crafts of the rural Tonga women.Footnote 35 The museum has cultivated a relationship with the rural women; it provides a craft shop where baskets are sold, and it buys baskets from women in at least four districts: Choma, Gwembe, Pemba, and Sinazongwe, which are then sold onwards in the global crafts market. The women have benefited from being affiliated with the museum, with invitations to exhibitions where they display their craftsFootnote 36 and sponsorships with non-governmental organizations and foreign embassies to promote Tonga heritage in general and the baskets more specifically.Footnote 37 The museum also offers specialized handicraft training in new designs and skills, which are intended to sharpen the women’s skills and provides them with training in life skills. The museum thus plays a unique role in merging cultural preservation and a socioeconomic agenda by promoting the sale of Tonga baskets.

Scholars, however, caution the involvement of third parties in placing Indigenous cultural heritage on the global market, noting the potential for the Indigenous community not to achieve the intended benefits.Footnote 38 In the case of the Tonga women, the museum acts as an intermediary between the women and the market, and it buys around 4,000 baskets per month from the women at a cost of about 60,000 Zambian kwacha (US $3,400). In other places, like Lusaka, one small basket costs about 20 Zambian kwacha (US $1.10), and, online, the baskets sell for between US $25 and US $75, which is a significant price difference. The women therefore do not reap as many benefits as the third parties. That said, given the fact that the museum’s existence is the result of government intervention through the National Museums Board of Zambia, there is some oversight of its activities. In addition, it must account to some of its donors, and, as such, it endeavors to maintain a working relationship that does not exploit the women.

TCEs and open collaborative innovation

Innovation is the development of new or improved products, processes, and marketing and organizational methods,Footnote 39 and when contextualized as open and collaborative, it entails “accessing, harnessing and absorbing flows of knowledge.”Footnote 40 Though normally conceptualized in terms of firm activities and organizations, it generally involves co-creation and cooperation,Footnote 41 activities engaged in by a group of people. Indigenous peoples have collaboratively generated knowledge, know-how, and practices for centuries.Footnote 42 Further, the environment within which Indigenous people create expressions of their cultural heritage, such as sculptures, pottery, baskets, plays, and so on, is generally collaborative – knowledge and skills sharing characterize the creative processes.

In addition, as traditional communities engage in daily life, change is constant, and communities invent new methods, skills, and tools and ways of creating. Article 11 of the UNDRIP provides that Indigenous peoples have the right to practice and revitalize their cultural traditions and practices, supposing that TCEs are not static and can evolve over time. Though rooted in the histories and cultural and spiritual values of Indigenous peoples, there is constant change. TCEs are part of the living heritage of Indigenous communities, and they are constantly being recreatedFootnote 43 and influenced by the changing needs of the Indigenous communities, socioeconomic conditions, and interactions in trade and commercial activities. For example, Ghanaian Kente cloth has changed continually from the pre-colonial era when European merchants introduced colored silk,Footnote 44 and Maasai beadwork has been influenced by interactions with the outside world, and each generation has adapted the designs to its own circumstances.Footnote 45

Women, IP, and TCEs

The IP regime, which on the face of it is gender neutral, is argued to have a gender bias.Footnote 46 The underlying concepts are steeped in gendered concepts, and scholars argue that inherent in IP is mind/body dualism, which is the distinction between mental and physical qualities.Footnote 47 For instance, in copyright, this distinction is manifested in the idea/expression dichotomy and, in patents, in the invention and industrial applicability/usefulness. The mind (rational, technical, and inventive) is often identified with masculinity, whereas the physical (natural, emotional) is often identified with femininity.Footnote 48 In addition, the picture of an inventor, historically, is dominantly male,Footnote 49 associating inventive activity with the male gender. Patent law further values scientific ingenuity (the rational and inventive), which has also been associated with masculinity.Footnote 50 IP dualism therefore “reinforces socially established structures of hierarchy within creative endeavour” – hence, an inherent bias in a perceived gender-neutral system.Footnote 51

Studies also evidence the unequal usage of the IP system with men constituting the bulk of IP users,Footnote 52 particularly with patents.Footnote 53 Discriminatory social and cultural practices limit women from being recognized as inventors, which is further compounded by the lack of access to resources.Footnote 54 Besides the gender inequality in the IP system, some work that is produced by women constitute TCEs. These are made openly and collaboratively, usually by women.Footnote 55 Though not recognized as IP, they are works of intellectual creativity, which to varying degrees exhibit innovativeness. Considering the appropriation of Indigenous arts and culture,Footnote 56 it raises questions about the exclusion of such works from protection, and scholars opine that the traditional knowledge from which TCEs develop “may be considered inferior feminine knowledge in contrast to the superior (and valuable) masculine knowledge of the developed, science-driven West.”Footnote 57

That said, the IP system is arguably an unsuitable regime for protecting TCEs.Footnote 58 The concepts of creation and incentives/rewards in the IP system are at odds with the customary practices and values of Indigenous peoples. Whereas the IP system envisages a sole creator or inventor,Footnote 59 cultural production in Indigenous communities is generally communal in nature, and the creative process and collaborative activities usually entail collective ownership.Footnote 60 There are challenges to using IP rights to protect TCEs – for example, under copyright law the legal requirements for authorship and limited duration of protection may not align with the characteristics of TCEs, which usually have no identifiable author.Footnote 61

Nonetheless, scholars note the potential applicability of IP rights to protect certain TCEs.Footnote 62 Among these IP rights include trademarks, as a branding strategy to identify and distinguish products.Footnote 63 Indigenous communities can use trademarks to brand their TCEs;Footnote 64 perhaps more appropriate are the collective trademarks that distinguish products of groups of producers.Footnote 65 An example is the collective trademark for Taita Baskets of Kenya,Footnote 66 a mark for sisal baskets made by women from Taveta County. Though no studies have examined the benefits of the registration, anecdotal evidence shows that before the registration of the mark the women sold their baskets for less than US $9, but since the mark became popular the price has increased to about US $15 per basket.Footnote 67 Researchers, however, highlight the difficulties and appropriateness of collective ownership strategies under trademarks.Footnote 68 Desmond Oriakhogba, in a study of Zulu bead makers, states that, even though the process is collective, the bead makers add their own individual style and creativity such that the beads can be considered their own creations.Footnote 69

The challenges around protecting TCEs within the IP system mean that a special system to protect TCEs is necessary. Arguments for sui generis (special) protection, which can address the unique characteristics of TCEs, have gained traction.Footnote 70 Such a system may borrow from IP principles but is adapted to ensure the protection of TCEs. Chidi Oguamanam suggests an approach where different types of TCEs receive different types or levels of protection.Footnote 71 Though no international agreement exists yet on the legal protection of TCEs, the topic has remained on the agenda of norm-setting organizations such as World Intellectual Property Organization.Footnote 72 Proponents for a sui generis system caution that there needs to be flexibility to accommodate the diversities of Indigenous communities around the world.Footnote 73 Besides global debates, regional initiatives in Africa have seen the adoption of the 2010 Swakopmund Protocol on the Protection of Traditional Knowledge and Expressions of FolkloreFootnote 74 within the Framework of the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO), from which the Zambian legislation derives inspiration.Footnote 75

TCEs protection in Zambia’s Traditional Knowledge Act

The Traditional Knowledge Act provides the legal framework for protection, access, and use of TCEs. It emphasizes the customary values and governance principles in protecting TCEs and embeds the spiritual, cultural, and social value of TCEs. The Act uses the term expressions of folklore and defines these to be any form, whether tangible or intangible, in which traditional culture and knowledge is expressed, appears, or manifests.Footnote 76 It outlines what constitutes expressions of folklore – verbal expressions, musical expressions, expressions by movement or incorporating movement, tangible expressions, and any other creative and cumulative activity of traditional community – and gives examples of each of these expressions.Footnote 77

In terms of section 47(1), TCEs are protected automatically from the time that they were/are created, and this protection subsists for as long as they remain considered expressions of cultural identity and traditional heritage.Footnote 78 There is no requirement for formalities or registration to obtain protection. The Act includes domestic and regional protection within the ARIPO framework, a vital provision considering territorial boundaries were arbitrarily drawn resulting in communities being separatedFootnote 79 – for example, the Tonga are found in Zambia and Zimbabwe.Footnote 80 The Act thus grants custodians of TCEs the right to register transboundary TCEs in accordance with the Swakopmund Protocol.Footnote 81 However, this does not negate the rights of the custodians in Zambia, as there is provision for registration in Zambia of TCEs that are shared with a community outside Zambia.Footnote 82 In such a situation, there may be a potential for conflict, and this is anticipated in section 4(4)(e), which states that holders of TCEs have the right to use alternative dispute settlement procedures at ARIPO to settle disputes arising from TCEs shared across national boundaries.Footnote 83

The Act also provides the right to register TCEs with ARIPO and obtain benefits arising from the commercial use of TCEsFootnote 84 and the right to give prior informed consent for the use of TCEs licensed with ARIPO.Footnote 85 The beneficiaries of TCE protection are the traditional communities who are the custodians in terms of the customary laws and practices and who maintain and use the TCEs as their cultural heritage.Footnote 86 They can license use of the TCEs, but such a licensing agreement must be approved by the Patents and Companies Registration Agency (PACRA).Footnote 87 The implication being that the PACRA can safeguard the interests of the traditional community. That could also explain why the PACRA has power to grant authorization to use TCEs, subject to a benefit-sharing clause and transferring the benefits to the traditional community.Footnote 88

Though TCE protection is automatic with no requirement for registration, according to section 47(2), notification to the PACRA may be required for evidentiary purposes for certain categories of TCEs that are of special cultural or spiritual value or sacred. Notification to the PACRA serves a declaratory function; it does not require documentation, recording, or public disclosure of the TCEs. The Act protects TCEs against infringement,Footnote 89 misappropriation,Footnote 90 and improper granting of IP rights.Footnote 91 An extensive list of unlawful acts without prior informed consent are contained in section 49 and include reproduction, publication and adaptation, and broadcasting,Footnote 92 use without attribution to the traditional community,Footnote 93 and distortion, mutilation, or other modification or derogatory action.Footnote 94 These provisions are similar to economic and moral rights under copyright. In addition, section 49(3)(b) prohibits false, confusing, or misleading indications – in relation to goods or services – that refer to, draw upon, or evoke TCEs of a traditional community – wording that mirrors geographical indication protection.

The protection of TCEs is subject to exceptions and limitations for education, research, and experimental purposesFootnote 95 and other non-commercial uses such as criticism, review, reporting, archiving, and private use.Footnote 96 In addition, section 50(1)(a) provides that the protection of TCEs must not restrict the normal development, use, exchange, dissemination, and transmission of TCEs within the traditional context by the traditional community. Protection extends only to uses outside the traditional context, regardless of whether it is for commercial use or not.Footnote 97 Exceptions and limitations, however, must be compatible with fair competition and practice, non-offensive, and acknowledge the traditional community that is the source of the TCEs.Footnote 98

The Traditional Knowledge Act provides sui generis protection to TCEs and also the right to protect IP rights relating to TCEs.Footnote 99 The Act does not expand on this provision, but the implication is that this means using conventional IP rights – patent, copyright, trademark, geographical indication – to the extent that it is possible. In this respect, the Act combines sui generis and IP protection. However, considering the extensive provisions on TCEs and the fact that there is no mention of TCEs in the other IP statutes, it seems sui generis protection for TCEs is the preferred regime.

Research findings and analysis

Tonga women and open collaborative innovation

It is a presumed role of women to make baskets; the baskets serve a utility function, they are used for winnowing, carrying harvest from the field, serving dry foods – activities associated with women. Gender thus impacts the baskets that the women make as the women understand the dimensions and shapes of the baskets due to their uses.Footnote 100 Chisuwo (big basket) is a versatile basket used to process millet, sorghum, maize, and groundnuts. It is also used to carry harvested grains from the field to the home and carry vegetables from the garden. Nsangwa (small basket) is used for storing or carrying mealie meal when cooking and to serve dry foods like groundnuts and roasted maize (Figure 1). It is also used to carry seed to the fields when planting. Though the baskets serve a utilitarian function, they are intricately woven and decorated showing an aesthetic appreciation.Footnote 101

Figure 1. Combination of different patterns on small baskets (Nsangwa)

The challenge identified by the women that arises due to their gender involved the time devoted to weaving. As there are defined gender roles, women sometimes find it difficult to set time aside to weave baskets as they must balance their daily household chores and weaving the baskets. According to one interviewee, “[d]uring the rainy season, there is more work to do as we plough the fields. It is difficult to do everything – daily household duties, work the fields and make baskets.”Footnote 102

Another challenge involved the travel logistics to collect materials for weaving the baskets. The women feared travelling to source the materials without male escort and therefore went as a group on appointed days when they hired a vehicle. They use malala (palm leaves), ntende (the creeping vine), nsamu (twigs), and other fibers to make the baskets, tough materials that ensure that the baskets last for a long time.Footnote 103 Tree bark is used to make the dye for the patterns of the baskets, a complex process that involves water and airtight containers. In some instances, cow dung is added to seal the baskets; these varieties are not sold but are reserved for the women themselves.Footnote 104

The environment within which the women weave the baskets is open and collaborative – from the gathering of materials, the sharing of tools, and the weaving of the baskets. There is a level of trust that is essential in collaboration,Footnote 105 and the women endeavor to maintain good relations among themselves. According to one interviewee, “[s]ometimes we receive a big order and because we make the baskets together, we can easily help each other to complete a big order.”Footnote 106

Creativity is both individual and collective, with the baskets belonging to the community. Organized around craft clubs, the women meet regularly to weave the baskets and set targets. Some meet once a week,Footnote 107 others twice a weekFootnote 108 or once month,Footnote 109 and they continue weaving at their homes. Meeting regularly enables the women to check on each other’s progress and the quality of the baskets. The women identified knowledge and skill sharing as an advantage of being part of a craft club as they exchange ideas, support each other, and sharpen each other’s skills and techniques. The older women teach the younger women how to weave the baskets, strengthen the materials used, and create the natural dyes. According to one interviewee, “[w]e are women of different ages and that helps us to share new ideas.”Footnote 110

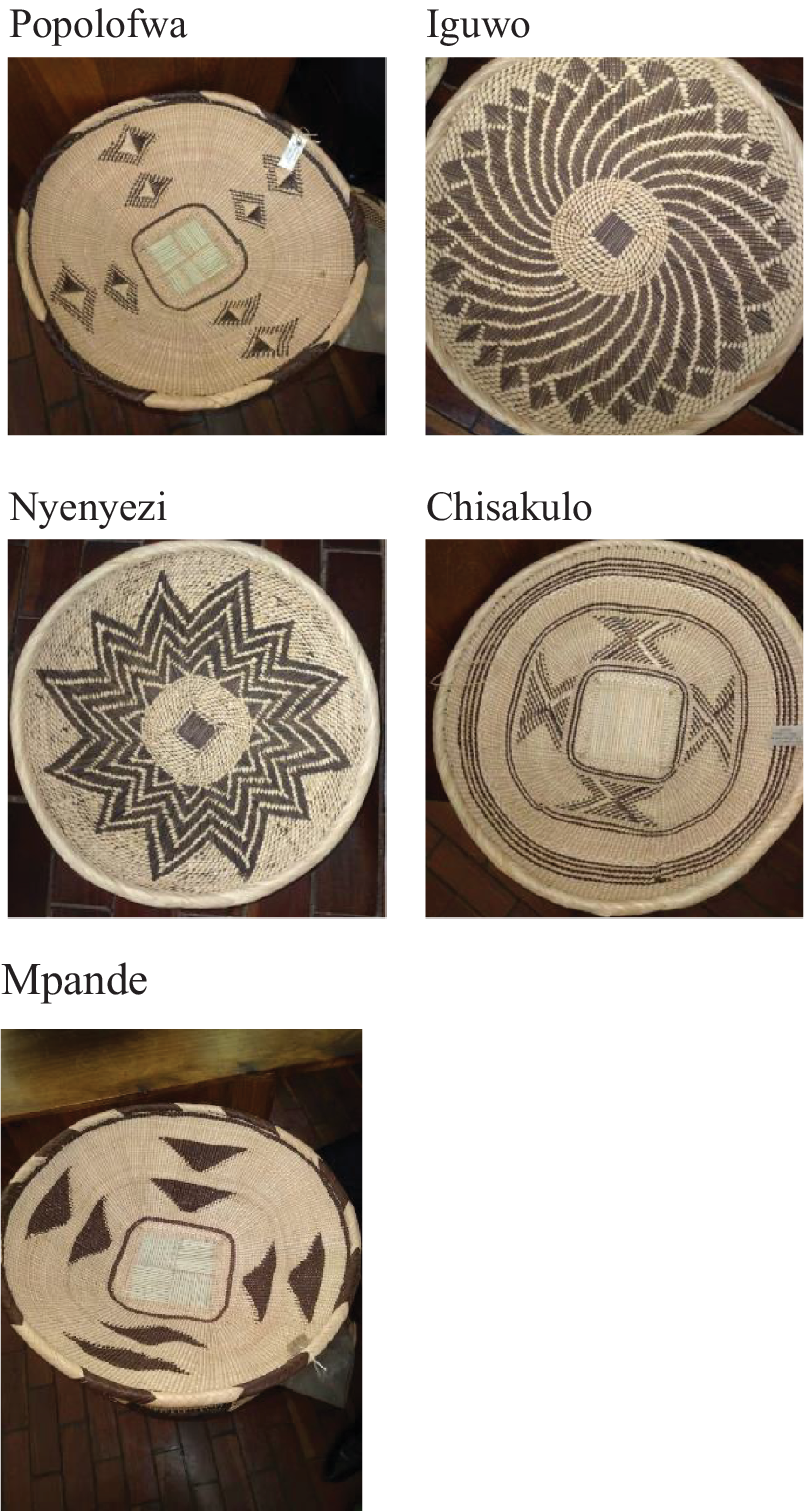

The women indicated that there are many inspirations behind their patterns, some from their history and culture, their traditions passed down from generations, and others from the environment that surrounds them (Figure 2). Among the popular patterns inspired by nature are popolofwa, a pattern that imitates the wings of a butterfly, iguwo, a flowing pattern reflecting the movement of the wind, and nyenyezi a pattern of the star. Other designs that draw from their history are chisakulo, a comb, which is central to women’s cosmetology and mpande, a pendant of ancient Tonga jewelry worn by queens and kings.Footnote 111

Figure 2. Some patterns of the baskets

The women interviewed in this study generally used the same patterns and designs with slight variations. Collaboration helps the women develop new patterns; they did not consider themselves to be in competition but in cooperation. They did not view the patterns as unique to themselves, but inspirations of their collective culture and environment, and they considered their knowledge and creations as belonging to the Tonga community.

Some of the baskets have undergone changes to suit aesthetic customer preferences, but the technique and materials used are based on the traditional method of weaving and dyeing the baskets. The shapes and sizes of some of the baskets have changed – for example, the Munyumbwe, Siabaswi, and Siansalama craft clubs adjusted their baskets to meet the specifications of the customers that want more of the small baskets than the big ones. Madyongo, Siampondo, and Sinazeze craft clubs have retained the traditional shapes and sizes of the baskets. The women balance preserving the distinct traditional styles of the baskets, while also creating innovative designs.

TCE and IP protection for Tonga baskets

The baskets are traditional cultural expressions; section 2 of the Traditional Knowledge Act specifically mentions baskets as tangible expressions of traditional culture. As discussed above, in terms of section 47(1), TCEs are protected automatically from the time they are created, and there are no formalities or registration required, as the baskets are de facto protected. According to the women, the baskets are not sacred or spiritual and therefore do not fall under the provisions of section 47(2), which provides that registration may be required for TCEs of spiritual or sacred value. The women, however, had no knowledge of TCEs and IP but recognized the value of their baskets, which they considered their collective heritage as Tonga people. According to an interviewee, “[i]t is a heritage given to us by our ancestors who used to make baskets from reeds when they lived by the Zambezi River before the Kariba Dam was built. We want to preserve it for future generations, it should not end with us our children should inherit it.”Footnote 112 The women showed an interest in registering the baskets as a form of ownership and preserving the heritage. One interviewee gave an emphatic response: “Yes, because our forefathers owned this knowledge, and it is part of our being as BaTonga.”Footnote 113

Registration can be a way to identify and distinguish the baskets from others made elsewhere on the continent, particularly as basket weaving is common in many countries. The Tonga are found in Zambia and Zimbabwe, and the women in both countries weave baskets. The transborder nature of this cultural heritage means that there could be two possible routes – registration of the Zambian Tonga community as holders of the TCE in Zambia, under section 47(4) of the Traditional Knowledge Act, and registration of a transboundary TCE, under section 4(4)(a) of the same Act. The Traditional Knowledge Act also provides for the right to protect IP rights relating to TCEs, as discussed above. The question is does the IP regime offer feasible options? The likely choices are copyright and trademark laws.

The Copyright and Performance Rights Act (Copyright Act) provides that copyright subsists in artistic works.Footnote 114 The baskets are composed of unique patterns and designs and can be considered artistic works pursuant to section 2(a) of the Copyright Act since works of craftsmanship are artistic works (see Figure 2). But the challenges of copyright protection for TCEs – that is, authorship and limited duration of protection – make this an unviable option.Footnote 115 The baskets are not the product of single or joint authorship as provided in section 2 and section 3(1) of the Copyright Act, respectively. There is no distinction of the contribution of each author as the baskets draw upon the cultural heritage of the traditional community. In addition, the duration of protection of copyright – the life of the author plus 50 years after their deathFootnote 116 – is at odds with the aim of protecting TCEs for as long as they remain expressions of cultural heritage, as contained in section 51 of the Traditional Knowledge Act.

Considering that the women expressed a willingness to protect the baskets collectively, the trademark system can be considered – for example, something similar to the collective trademark for Taita baskets of Kenya. The 1958 Trade Marks Act does not provide a collective trademark, but it does provide a certification mark, which is a mark used to distinguish goods certified in respect of origin, material, mode of manufacture, quality, or other characteristic of the goods, from goods not so certified.Footnote 117 The baskets can be certified, for example, with respect to origin, material, or quality. However, a certification mark cannot be registered in the name of a person who carries on trade in the goods certified,Footnote 118 and this means setting up a certifying authority, independent of the Tonga women who make the baskets. The main limitation of this option is that it removes control from the women and goes against the spirit of Article 31(1) of the UNDRIP, which gives Indigenous people the right to maintain, control, and protect their cultural heritage. The IP system therefore does not offer viable options to protect the Tonga baskets.

Basket weaving and women empowerment

Though the women engage in subsistence farming for their livelihood, most of the women (47) largely depended on selling baskets as their main source of income. It has improved the welfare of the women, enabling them to provide for their families and give them some control over their lives. The museum buys the baskets in bulk and pays the women, who then distribute the proceeds among themselves. How much each woman gets depends on how many baskets and the sizes she has contributed within the craft club, and this amount can range from $30 to $300. As one interviewee explained, “[w]ith the money I have made from the baskets I have bought cattle and sent my children to school.”Footnote 119 The women gained some financial autonomy and were able to direct money for family needs such as education for their children and the purchase of clothes and food.

Weaving baskets also enhances the women’s pride in their culture since they consider basket weaving a way of preserving Tonga culture, which they feel is threatened as youth have less interest in learning their culture. They believe that, as more young women learn how to weave the baskets, the tradition will remain alive.Footnote 120 The older women also see the passing down of their knowledge to the younger women as a way of helping them to become independent and provide for themselves by using their skills. One interviewee stated: “Women are the backbone of the household. A man will not always provide for you and that is why we teach our daughters to make baskets so that they can sell and feed their families.”Footnote 121 The young women that join the craft clubs learn to weave baskets and earn a living, particularly as there are limited opportunities for formal employment in rural areas and they do not have sufficient qualifications for formal employment. According to another interviewee, “[a]fter I finished school, I could not find a job. My mother invited me to join the club. I had never made baskets before, but I learnt from the other women.”Footnote 122

The women benefit from being able to negotiate a good price for the baskets in the craft clubs, which the women said was better than selling as an individual.Footnote 123 According to the women, it ensures everyone gets a share, and, in this context, collaboration is a way to control the price.Footnote 124 Since the baskets have gained prominence in the market, the women have also seen an increase in their earnings. In addition, the craft clubs are a place of social interaction, support, and encouragement. The women exchange ideas on marriage, family, and other social challenges. They contribute financially to support each other through what they call chilimba, where each time they sell baskets, they give one member an agreed amount. This system allows the member to invest the money in an item of value that they otherwise would not afford on their own – for instance, household furniture and cattle. The support that the women give each other improves their relationships among themselves and contributes to the overall uplift of the women.

Conclusion

Basket weaving is the presumed role of the Tonga women, and because the baskets serve a utility function in the home, the women understand the design, shapes, and materials for weaving the baskets. Gender therefore plays a role in the creative process of the women. Open collaborative innovation is central to their craft as the women share ideas, patterns, tools, and materials, drawing on their traditional knowledge. They sharpen each other’s skills and techniques, do quality checks, and negotiate prices for their baskets within their craft clubs. The Tonga baskets demonstrate that traditional cultural expressions are not static but, rather, evolve with constant innovation as each generation adds its own impression and adapts to its unique needs and context.

With limited education and opportunities for formal employment, the women support their families by weaving and selling baskets. It makes them feel self-reliant and in control of their lives. Cultural production is improving the lives of the Tonga rural women, and it has enhanced their socioeconomic lives. The women’s relationship with the museum has facilitated a wider reach of the baskets beyond Zambia – in that context, the museum preserves the cultural heritage and supports the women. In at least three ways, the museum supports the women – exhibiting the baskets, facilitating the sale of the baskets, and offering life skills to the women. The museum merges cultural preservation and a socioeconomic agenda by promoting the sale of Tonga baskets.

Considering that the baskets have become a significant source of income for rural women, and the suggestions for a branding strategy, a strategy to identify and distinguish the baskets from others on the global craft market could be ideal. However, IP laws do not offer feasible choices. Limitations in copyright law, as it relates to the authorship and duration of protection, make it an unviable option. The trademark law does not provide for collective trademark, which could indicate the origin of the baskets from the Tonga women. A special system is the better option. The Traditional Knowledge Act provides automatic protection to traditional cultural expressions, and, as such, the baskets are by default protected. Registration, as provide by the Act, could be a way to identify the baskets and a step in enhancing the recognition of the baskets in the global crafts market.