To the Editor—The effectiveness of healthcare improvement initiatives is highly dependent on the social, psychological, organizational and cultural dynamics of clinical settings. Reference Coles, Wells and Maxwell1,Reference Ovretveit2 Historically, in antimicrobial stewardship, most interventions have been broadly implemented without taking these important contextual factors into account, despite research demonstrating the importance of adaptation to the local context. Reference Lorencatto, Charani, Sevdalis, Tarrant and Davey3,Reference Sikkens, van Agtmael and Peters4 Furthermore, the recommended metrics for assessing the impact of interventions do not take into consideration the dynamics between the clinician and antimicrobial stewardship team, making it more difficult to predict the long-term success of a program. Reference Moehring, Anderson and Cochran5 Existing behavior-change models can be applied to determine how the intended recipient of an intervention might respond to initiatives that seek to change behavior in order to optimize the uptake and sustainability of antimicrobial stewardship interventions.

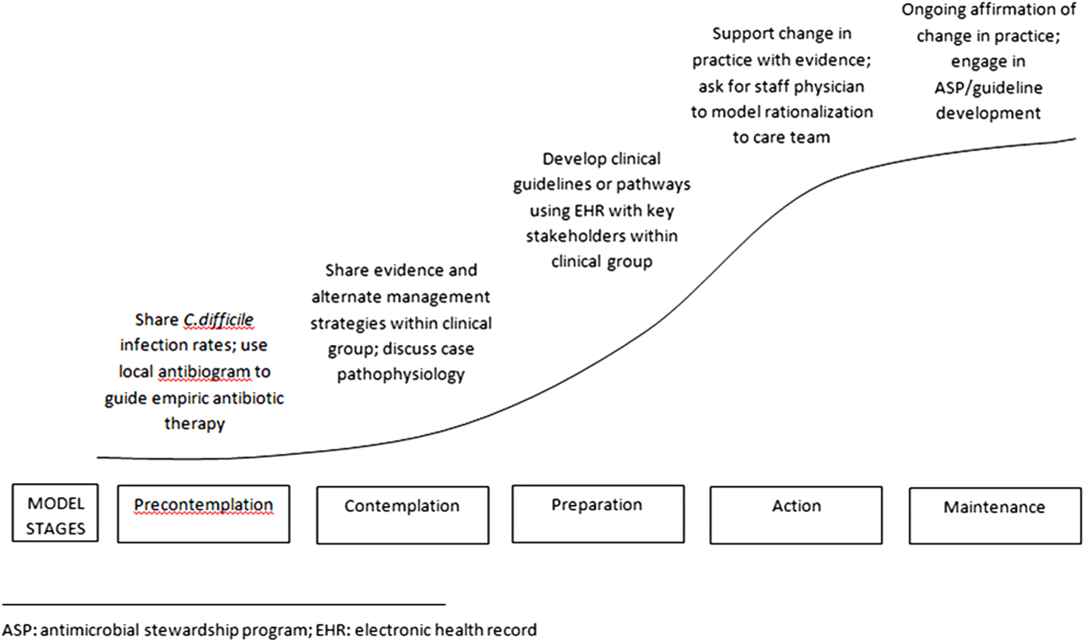

Prochaska and DiClemente’s transtheoretical model (TTM) is one such framework. It consists of 5 stages that conceptualize how people change their health behavior. Reference Prochaska, Prochaska and Levesque6 In the initial stage, precontemplation, the individual does not intend to take action within the next 6 months. In stage 2, contemplation, action is intended within the next 6 months. Stage 3 is preparation, in which action is intended within the next 30 days; stage 4 is action, in which behavior has recently changed; and stage 5 is maintenance, in which behavior changes are sustained for >6 months.

Although this model was initially used to understand behavior change associated with smoking cessation, it has been broadly applied to infection prevention and control, demonstrating both the value in understanding motives among clinicians to adhere to standard precautions and success with stage-matched interventions aimed toward improving adherence to standard precautions and hand hygiene compliance. Reference Livshiz-Riven, Nativ, Borer, Kanat-Maymon and Anson7,Reference Pontivivo, Rivas, Gallard, Yu and Perry8 Figure 1 highlights the practical application of the TTM during an antimicrobial stewardship encounter between a frontline clinician and an antimicrobial stewardship clinician. For example, when the clinician may not perceive a need to decrease his/her fluoroquinolone use (precontemplation stage), the antimicrobial stewardship interaction highlights recent local cases of Clostridioides difficile that followed fluoroquinolone use. Discussions that review case pathophysiology, including the evidence for an infection, and discussions that raise consciousness about peer prescribing practices can support a clinician who is contemplating a change in their prescribing behaviors (contemplation stage). In contrast, the clinician who already self-initiates reassessment of antimicrobial therapy (action stage) would not benefit from reviewing the rationale for stewardship because they are already committed to making behavioral changes. Rather, affirmation on rounds and engagement in guideline development would reinforce the changes already being made and move the clinician into the maintenance stage.

Fig. 1. Transtheoretical model with stages of change and application to discussions of antimicrobial misuse.

For behavior change to occur, the TTM posits that clinicians must pass through all stages of change. Failure to tailor antimicrobial stewardship initiatives to the recipient’s stage of change may delay progress or even cause regression to earlier stages. When behaviors are easy to change and resistance is low, the specific stage of change may matter very little. In such situations, brief interventions and messages may be all that are needed to help clinicians progress through the stages. In contrast, where the change is perceived as difficult and is associated with resistance, there is a greater need to provide deliberate messaging and individualized, stage-matched interventions.

The effectiveness of antimicrobial stewardship interventions has been studied widely, yet significant knowledge gaps exist related to the impact of clinicians’ readiness to adopt these practice changes on antimicrobial stewardship outcomes. Because success of the same antimicrobial stewardship intervention can vary across clinical networks, metrics that take into account the dynamics between prescribers and the antimicrobial stewardship team can provide insight into how well an intervention will be incorporated into the local culture of practice. Reference Sikkens, van Agtmael and Peters4,Reference Moehring, Anderson and Cochran5,Reference Charani, Ahmad, Rawson, Castro-Sanchez, Tarrant and Holmes9,Reference Elango, Szymczak, Bennett, Beidas and Werner10 Further research identifying, measuring, and accounting for stages of behavioral change in the evaluation of antimicrobial stewardship improvement strategies will provide insight into how to adapt and integrate these initiatives across various healthcare settings.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.