1. Introduction

Mental disorders are highly prevalent and major contributors to the global burden of disease, accounting for 7.4% of the disease burden and representing the leading cause of non-fatal disease burden worldwide [Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari and Erskine1]. From a public health perspective, disability became as important as mortality to set priorities and resources’ allocation in health systems [Reference Caldas-de-Almeida, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Loera, Alonso, Chatterji and He2, Reference Ormel, Petukhova, Chatterji, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso and Angermeyer3]. Disability is conceptualized as the experience of an individual with a health condition in interaction with contextual factors [Reference Leonardi, Bickenbach, Ustun, Kostanjsek and Chatterji4], and it is defined as the reduction of an individual’s capacity to function, encompassing activity limitations or participation restrictions [Reference Porta5–Reference World Health Organization7]. The impact of disability associated with mental disorders in role functioning and quality of life is exacerbated by the early age of onset and recurrent or chronic course of many mental disorders [Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha and Bryson8], in addition to substantial unmet needs for treatment [Reference Ormel, Petukhova, Chatterji, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso and Angermeyer3, Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts, Posada-Villa, Gasquet, Kovess and Lepine9].

Mental disorders represent a challenge to health systems due to high prevalence rates, associated disability and inherent societal costs [Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari and Erskine1, Reference Bloom, Cafiero, Jané-Llopis, Abrahams-Gessel, Reddy Bloom and Fathima10–Reference De Graaf, Tuithof, Van Dorsselaer and Ten Have13]. In 2010, mental disorders had an estimated cost of €461 billion in Europe as a result of high direct health costs and even higher indirect costs due to productivity loss [Reference Gustavsson, Svensson, Jacobi, Allgulander, Alonso and Beghi12]. At the individual level, people with disability related to mental disorders are at higher risk of exclusion from the labour market, which may further exacerbate existing social inequalities [Reference Karpov, Joffe, Aaltonen, Suvisaari, Baryshnikov and Näätänen14, Reference Emerson, Madden, Graham, Llewellyn, Hatton and Robertson15].

The World Mental Health Survey (WMHS) Initiative was designed to evaluate the prevalence, severity, distribution and consequences of mental disorders through the collection of cross-nationally representative epidemiological data using standardized methods worldwide [Reference Xavier, Baptista, Mendes, Magalhães and Caldas-de-Almeida16, Reference Kessler, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Chatterji, Lee and Ormel17]. In Portugal, the WMHS Initiative is the only population survey of psychiatric morbidity with a nationally representative sample [Reference Caldas-de-Almeida and Xavier18].

Analysis of the WMHS Initiative data in Europe showed that Portugal and Northern Ireland are the countries with the highest 12-month prevalence of any mental disorder [Reference Pinto-Meza, Moneta, Alonso, Angermeyer, Bruffaerts and Caldas-de-Almeida19]. The prevalence rate of 22.9% found in Portugal is particularly high when compared with other Southern European countries such as Italy and Spain, where prevalence rates of 9.7% and 8.8% were found, respectively [Reference Kessler, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Chatterji, Lee and Ormel17, Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Thornicroft, Szmukler, Mueser and Drake20]. In the spectrum of mental disorders, the most prevalent conditions are mood and anxiety disorders, designated as common mental disorders [21]. Considering the high 12-month prevalence of these disorders in Portugal and the growing literature quantifying its societal costs [Reference Bloom, Cafiero, Jané-Llopis, Abrahams-Gessel, Reddy Bloom and Fathima10–Reference Alonso, Petukhova, Vilagut, Chatterji, Heeringa and Üstün12, Reference Gustavsson, Svensson, Jacobi, Allgulander, Alonso and Beghi22–Reference Cardoso, Xavier, Vilagut, Petukhova, Alonso and Kessler24], it is important to characterize the burden of common mental disorders in terms of disability at the country level. Studies in this area tend to evaluate disability through the lenses of productivity loss, using indicators such as days out of role [Reference Alonso, Petukhova, Vilagut, Chatterji, Heeringa and Üstün11, Reference Cardoso, Xavier, Vilagut, Petukhova, Alonso and Kessler24], work performance [Reference De Graaf, Tuithof, Van Dorsselaer and Ten Have13, Reference Barbaglia, Duran, Vilagut, Forero, Haro and Alonso23], sickness absence [Reference Knudsen, Harvey, Mykletun and Øverland25, Reference Sumanen, Pietiläinen, Lahelma and Rahkonen26] or early retirement [Reference Lahelma, Pietiläinen, Rahkonen and Lallukka27], but do not address the overall impact of common mental disorders in functioning and well-being.

This study aims to characterize the disability associated with common mental disorders in Portugal, using the modified version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule for the WMHS Initiative (WMHS WHODAS-II), a multi-dimensional assessment of disability, in order to provide an evidence-based framework for health policy strategies and interventions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

The WMHS Initiative, carried out in Portugal between October 2008 and December 2009, is a cross-sectional study based on a stratified multistage clustered area probability household sample. It was administered at the households of a nationally representative sample of respondents. The participants were Portuguese-speaking adults aged 18 or above and residing in permanent private dwellings in Portugal’s mainland. Informed consent was obtained before the interviews and the procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nova Medical School (NOVA University of Lisbon). The survey was conducted by trained lay interviewers on a face-to-face setting, based on a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) methodology. The response rate obtained was 57.3%, similar to the surveys in Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. No substitutions from the initially selected households were allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed [Reference Xavier, Baptista, Mendes, Magalhães and Caldas-de-Almeida16].

In order to reduce the respondent burden, internal subsampling was used by dividing the questionnaire in two parts. Part I included the core diagnostic assessment of mental disorders. All respondents meeting the criteria for any DSM-IV disorders also completed Part II, together with a probability sample of 25% randomly selected participants who did not meet criteria for any disorder. Part II also included additional information, such as assessment of disorders of secondary interest, predictors and consequences of mental disorders and use of services. The total number of interviews was 3849 and both modules (Part I and Part II) were administered to 2060 participants. Part I data was weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of selection (between and within households), non-response bias and discrepancies between the sample and the sociodemographic and geographic data distribution from the census population. Part II was additionally weighted in order to adjust for the differential sampling of Part I participants into Part II. Further details regarding the study design and fieldwork procedures can be found elsewhere [Reference Xavier, Baptista, Mendes, Magalhães and Caldas-de-Almeida16].

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. 12-month mental disorders

Mental disorders present in the 12 months before the interview were assessed with the version 3.0 of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a fully-structured diagnostic interview, administered by trained lay interviewers [Reference Kessler and Üstün28].

A clinical reappraisal study, carried out in the WMHS Initiative in France, Italy, Spain and the United States, compared the diagnoses generated by the CIDI 3.0 with those generated by the clinician-administered non-patient edition of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) [Reference First, Gibbon, Hilsenroth, Segal and Hersen29, Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, De Girolamo, Guyer and Jin30]. This study showed a good concordance between the CIDI 3.0 and SCID estimates for 12-month mental disorders [Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, De Girolamo, Guyer and Jin30].

The diagnoses of common mental disorders, assessed using the criteria of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [Reference American Psychiatric Association31], are grouped in the two following categories: 1) anxiety disorders (panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and adult separation anxiety); and 2) mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia and bipolar disorder including bipolar I and II).

2.2.2. Disability (WMHS WHODAS-II)

Disability was assessed with the modified version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-II) for the WMHS Initiative (WMHS WHODAS-II), based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Framework [Reference World Health Organisation6, Reference World Health Organization7], and applied to the participants of the Part II sample. Difficulties in the 30 days prior to the assessment are evaluated in the following domains:

1) Understanding and communication (cognitive domain);

2) Moving and getting around (mobility domain);

3) Personal hygiene, dressing, eating and ability to live alone (self-care domain);

4) Interaction with other individuals (social interaction domain);

5) Difficulties carrying out work or normal activities (time out of role domain).

A global disability score aggregating all domains scores was calculated. Domains scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores meaning greater disability. The internal consistency and validity of the WMHS WHODAS-II have been demonstrated [Reference Von Korff, Crane, Alonso, Vilagut, Angermeyer and Bruffaerts32]. Given the distributional properties of the instrument, the global disability score was dichotomized at the 90th percentile to indicate the presence or absence of substantial disability, following the recommendations of Von Korff et al. [Reference Von Korff, Crane, Alonso, Vilagut, Angermeyer and Bruffaerts32].

2.2.3. Covariates

Gender and age were considered as covariates to adjust for possible differences in the experience of disability. The models were also adjusted for education, assessed through the number of years of education as a continuous variable. Education is widely used as an indicator of socioeconomic position [Reference Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch and Davey Smith33] and research indicates an educational gradient in the experience of disability due to mental disorders [Reference Sumanen, Pietiläinen, Lahelma and Rahkonen26].

The presence of any physical disorder was also considered as a covariate given that comorbidity between physical and mental disorders is associated with higher levels of disability [Reference Scott, Von Korff, Alonso, Angermeyer, Bromet and Fayyad34, Reference Kessler, Ormel, Demler and Stang35]. Physical disorders were assessed with a chronic disorders checklist that has shown good concordance with medical records [Reference Knight, Stewart-Brown and Fletcher36, Reference Baker, Stabile and Deri37]. Likewise, to avoid the influence of comorbidity between mental disorders on the disability reported by individuals [Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha and Bryson8], a variable was created to include the presence of all other common mental disorders in relation to each diagnosis.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Frequencies and chi-square tests (χ2) were used for descriptive analysis. Multiple logistic regression models were performed to evaluate the association between disability and common mental disorders, both at individual diagnoses level or grouped in the respective category of mood or anxiety disorders. All estimates were weighted according to the characteristics of the study, as previously explained [Reference Xavier, Baptista, Mendes, Magalhães and Caldas-de-Almeida16]. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used throughout the analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM® SPSS® Statistics), version 21.0.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

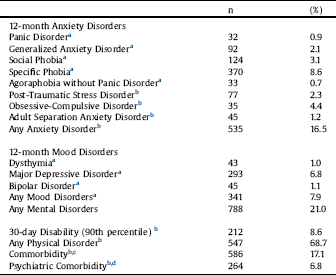

In terms of demographic characteristics, 51.6% (n = 2217) of the 3849 participants interviewed were women. The mean age was 46.38 years (standard deviation = 16.88) and the mean years of education were 8.76 (standard deviation = 4.79). The prevalence rates of common mental disorders and disability are presented in Table 1. Anxiety disorders were found to be the most prevalent common mental disorders in Portugal (16.5%), with specific phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder being the most prevalent conditions. The overall prevalence of mood disorders was 7.9%, with major depressive disorder being the most prevalent condition (6.8%).

The majority of the participants (68.7%) reported at least one physical disorder. The co-occurrence of any common mental disorder and any physical disorder was found in 17.1% of the participants and the co-occurrence of two or more common mental disorders in 6.8%.

The 30-day prevalence of disability was 8.6%. Among individuals with any common mental disorder, 14.6% (n = 115) reported disability (χ2 = 24.98; p < 0.001). In the group of participants with any anxiety disorder, 13.5% (n = 83) reported disability (χ2 = 12.64; p < 0.001), while among those with any mood disorder this rate was 21.6% (n = 71) (χ2 = 40.36; p < 0.001).

Table 1 Sample sizes (n), 12-month prevalence rates of common mental disorders and 30-day prevalence of disability in Portugal.

a % with Part I weight.

b % with Part II weight.

c Presence of at least one common mental disorder and one physical disorder.

d Presence of two or more common mental disorders.

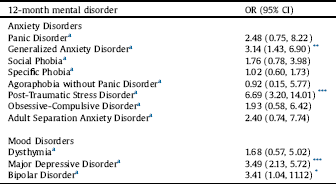

3.2. Association between disability and common mental disorders

The association between disability and each psychiatric diagnosis is presented in the form of odds ratios (OR) in Table 2. Generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder had a statistically significant association with disability, after adjusting for age, gender, education, presence of any physical condition and any other common mental disorder. The most disabling condition was post-traumatic stress disorder (OR: 6.69; 95% CI: 3.20, 14.01).

Table 3 shows the association, interpreted by the OR, between disability and common mental disorders, grouped as mood and anxiety disorders. The results indicate that both categories were significantly associated with disability, after adjusting for age, gender, education and presence of any physical disorder. Participants with any mood disorder presented 3.94 (95% CI: 2.45, 6.34) higher odds of reporting disability, when compared with people without mood disorders. Participants with any anxiety disorder were 1.88 (95% CI: 1.23, 2.86) more likely to report disability, when compared to those without any anxiety disorder.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to characterize the association between disability and common mental disorders in Portugal, where these disorders are highly prevalent [Reference Caldas-de-Almeida and Xavier18, Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Thornicroft, Szmukler, Mueser and Drake20]. The findings indicate that around 15% of individuals with any common mental disorder reported disability. This proportion varies between 13.5% and 21.6% when considering individuals with any anxiety or any mood disorder, respectively. Both anxiety and mood disorders were associated with disability but, as a group, mood disorders were found to be more disabling. When specific diagnoses were evaluated, post-traumatic stress disorder was found to be the most disabling condition. The odds of individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder reporting disability were six times higher when compared to those without the diagnosis. The core symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as repeated and intrusive memories of trauma, avoidance of situations or reminders of trauma and hyperarousal, have been associated in other studies with reduced quality of life, high distress and suicidal behaviour [Reference Sareen, Cox, Stein, Afifi, Fleet and Asmundson38], which may offer some explanation for the association found in our study.

Table 2 Odds ratios of anxiety and mood disorders, corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values obtained by multiple logistic regression models with disability as outcome variable.

a Part II weight. OR: odds ratio. CI: Confidence interval.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

Table 3 Odds ratios of any anxiety and any mood disorder, corresponding 95% CI and p-values obtained by multiple logistic regression models with disability as outcome variable.

aPart II weight. OR: odds ratio. CI: Confidence interval.

All models adjusted for age, gender, education and presence of any physical disorder.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001

In the group of anxiety disorders, generalized anxiety disorder was also associated with disability. In relation to mood disorders, both major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder showed a statistically significant association with disability. Overall, people with generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder were at least three times more likely to report disability when compared to those without each respective disorder.

These results are consistent with other research in this area. Alonso et al. examined the days out of role due to common physical and mental disorders in 24 countries that participated in the WMHS Initiative, classified according to the World Bank income categories. The mental disorders with higher mean days out of role per year were found to be post-traumatic stress disorder, followed by panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, for countries from all income groups. The adjusted additional days out of role among individuals with a disorder indicated post-traumatic stress disorder as the most disabling mental disorder in high-income countries [Reference Alonso, Petukhova, Vilagut, Chatterji, Heeringa and Üstün11]. In a recent study, the same evaluation was conducted for the Portuguese population and post-traumatic stress disorder was also found to be the mental disorder with the highest effect on days out of role, both at individual and at societal level [Reference Cardoso, Xavier, Vilagut, Petukhova, Alonso and Kessler24]. The societal cost of mental disorders in Portugal was higher in comparison to the results found by Alonso and colleagues in the group of high-income countries, with 20.2% of all days out of role in the last 30 days versus 11.3%, respectively [Reference Alonso, Petukhova, Vilagut, Chatterji, Heeringa and Üstün11, Reference Cardoso, Xavier, Vilagut, Petukhova, Alonso and Kessler24]. By using days out of role as a single indicator of disability, these studies do not assess other consequences of disability, such as reduced work performance and role functioning limitations, which may lead to an underestimation of the indirect costs of common mental disorders [Reference Cardoso, Xavier, Vilagut, Petukhova, Alonso and Kessler24, Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec and González-Fraile40]. However, this approach makes a strong case for investment in mental health, by indicating the economic return of mental health interventions, at the prevention and treatment levels. The results of the present study complement those found by Cardoso et al. [Reference Cardoso, Xavier, Vilagut, Petukhova, Alonso and Kessler24] by assessing disability related functional difficulties at the individual-level in the cognitive, mobility, self-care and social dimensions. This approach allows to map the differential impact of common mental disorders in disability and acknowledges its broad individual-level consequences. The results may also inform clinical practice, further highlighting the issue of under-treatment, since research has shown that only a minority of people with mental disorders receive adequate treatment [Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Thornicroft, Szmukler, Mueser and Drake20]. For instance, in the case of major depressive disorder, which can reliably be diagnosed and treated at the primary health care level, several barriers to the delivery of care have been identified, such as scarcity of resources or low levels of help seeking behaviour [Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson and Aguilar-Gaxiola39]. A recent study showed that the level of minimally adequate treatment among people with major depressive disorder in Portugal is among the lowest across high-income countries participating in the WMHS Initiative [Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson and Aguilar-Gaxiola39]. Research should evaluate access and trajectories of care in order to prevent and reduce the burden of disability associated with common mental disorders, particularly at the primary health care level, which should constitute the first line of approach to address the mental health needs of the population [Reference Martin-Carrasco, Evans-Lacko, Dom, Christodoulou, Samochowiec and González-Fraile40]. Moreover, as disability emerges from the interaction of an individual with any given disorder with contextual factors, this study provides a framework to further evaluate how social, economic and environmental factors may influence the association of disability and common mental disorders.

4.1. Limitations and strengths of the study

The results of this study should be interpreted taking into consideration several limitations. First, given the cross-sectional design of the study, causal inference and generalization of results are limited. Additionally, the changes made to the WHODAS-II instrument in the WMHS Initiative to reduce respondent burden, such as the use of filter questions, impaired the measurement properties with scores having highly skewed distributions, with low mean and large proportions of zero scores [Reference Von Korff, Crane, Alonso, Vilagut, Angermeyer and Bruffaerts32]. To address this issue, the cut-off for defining substantial disability (percentile 90th) has been recommended. However, this procedure may mask cross-national differences and caution is needed when comparing the results obtained in this study with those from other countries [Reference Von Korff, Crane, Alonso, Vilagut, Angermeyer and Bruffaerts32].

It is important to point out that, similarly to other studies in this area of research, disability was evaluated in the preceding month, whereas mental disorders are 12-month based. For episodic conditions, the past month disability may not include the time period of the disorder. On the other hand, using a 12-month diagnosis allows the inclusion of remitted disorders that may have residual adverse effects on disability [Reference Alonso, Petukhova, Vilagut, Chatterji, Heeringa and Üstün11, Reference De Graaf, Tuithof, Van Dorsselaer and Ten Have13]. Another limitation of this study was the inability to evaluate if the individuals with disability due to common mental disorders had been previously diagnosed and had received adequate treatment. Moreover, despite adjusting the multivariate models for education, this study did not assess the role of other socioeconomic factors, such as professional situation or financial hardship, in the association between disability and common mental disorders.

Finally, this study fails to account for the recent macroeconomic changes in the Portuguese context. Portugal was among the European countries most affected by the global financial crisis [Reference Legido-Quigley, Karanikolos, Hernandez-Plaza, de Freitas, Bernardo and Padilla41], and mental health and well-being are likely to have deteriorated more immediately and severely than other health outcomes [Reference Marmot, Bloomer and Goldblatt42]. Since the results presented in this study may underestimate the current epidemiological context, studies evaluating the consequences of economic recession on the prevalence of common mental disorders and associated disability are needed.

In spite of these limitations, the findings of the present study provide a better understanding of the association between disability and common mental disorders in the Portuguese context, which poses serious challenges to several sectors of governance.

This study follows the approach of previous authors [Reference Sanderson and Andrews43], which have argued that limiting the concept of disability only to severe conditions is likely to underestimate the individual and societal costs of mental disorders. In terms of public mental health, the use of disability as an indicator of the consequences of common mental disorders is useful at two main levels. First, as mental health services have continuously struggled for adequate funding allocation, using disability as an outcome variable allows the comparison with other health conditions, making a strong advocacy case towards investing in mental health [Reference Ormel, Petukhova, Chatterji, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso and Angermeyer3, Reference Sanderson and Andrews43]. Second, resource allocation decisions should continuously require information on disability [Reference Ormel, Petukhova, Chatterji, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso and Angermeyer3], which has been considered a reliable indicator to set priorities within the field of mental health [Reference Sanderson and Andrews43], for which this study may contribute in the Portuguese context.

4.2. Conclusions

The findings of this study have several implications for health policy and reinforce the need for investment in mental health. In terms of public health agenda, particular attention should be given to the burden of disability associated with anxiety disorders in Portugal. Despite being highly prevalent and disabling, these conditions are often less visible and under-prioritized in comparison to mood disorders, specifically depression.

The identification of the specific disorders associated with disability may also contribute to the development of interventions aimed at prevention efforts and promoting the functioning and quality of life of the affected individuals. However, as disability depends both on the nature of the mental disorder and the context in which individuals live, more research on this area is needed to properly evaluate and address potential health inequalities.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

AA receives a grant from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) [grant number PD/BD/105822/2014].

The Portuguese Mental Health Study was carried out by the Department of Mental Health, NOVA Medical School, NOVA University of Lisbon, with collaboration of the CESOP–Portuguese Catholic University and was funded by the Champalimaud Foundation, the Gulbenkian Foundation, the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and the Ministry of Health. The Portuguese Mental Health Study was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization WMH Survey Initiative which is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the U.S. Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho- McNeil Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the Nova Medical School, Nova University of Lisbon, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the World Mental Health Survey Initiative staff for their assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. A complete list of funding support and publications can be found at: http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.