Introduction

Stigma is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that can have multiple, detrimental effects on individuals, family members and society (Wahl and Harman, Reference Wahl and Harman1989; Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Druss and Perlick2014). In the case of mental health, stigma has been identified as sometimes being more distressing and debilitating than the illness itself (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2003). Various studies have reported on the nature of stigma, its types and effective interventions. However, most of the evidence on the topic comes from high-income countries (HICs). Reviews conducted of effective interventions to reduce mental health stigma showed very few studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Semrau et al., Reference Semrau, Evans-Lacko, Koschorke, Ashenafi and Thornicroft2015). Although stigma and discrimination are considered universal phenomena, their manifestations may vary according to culture and contexts. Cultural context is known to influence many aspects of mental disorders (Alarcón et al., Reference Alarcón, Becker, Lewis-Fernández, Like, Desai, Foulks, Gonzales, Hansen, Kopelowicz, Lu, Oquendo and Primm2009). Developing a stigma intervention and measuring its effectiveness in a particular setting is a challenge if the context-specific understanding of stigma, its causes and manifestations are missed.

One way to understand this cultural context is evaluating ‘what matters most’, an approach that conceptualises structural stigma as a moral experience and explains how threats to personal and group identity, or what is most at stake, may lead to stigmatizing behaviours (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Chen, Sia, Lam, Lam, Ngo, Lee, Kleinman and Good2014a). In healthcare settings, a provider's role as a healer in society may be jeopardised when encountering a patient with mental disorders whom they are not equipped to care for – this should be considered along with threats to other societal norms and values that are shaped by the provider's life experience, gender, caste, ethnicity and religion (Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1999; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Kleinman, Link, Phelan, Lee and Good2007). By identifying stigma as a moral experience and addressing what matters most, anti-stigma interventions can be better tailored to local contexts.

There is a growing burden of mental disorders in Nepal, an LMIC in South Asia. However, fewer than 10% of people with mental disorders receive any form of treatment (Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Kohrt, Rathod and Komproe2017). There are various supply-side challenges to this treatment gap, such as lack of mental health services in primary healthcare, and lack of regular supply of medicines (Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Kohrt, Rathod and Komproe2017). However, on the demand side, stigma related to mental disorders has been identified as a dominant barrier to mental healthcare (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs, Morgan, Rüsch, Brown and Thornicroft2015). Despite this, limited studies have been conducted to understand the local context and concepts of stigma in Nepal. Therefore, we conducted this scoping review to understand the stigma in the context of Nepal. The aim of this study was to synthesise the literature on mental health stigma in Nepal and understand stigma processes. Stigma processes include drivers, manifestations and consequences of stigma and the influence of ‘what matters most’ on these processes in the context of Nepal.

Methods

We employed a scoping review method (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) with a focus on exploring the literature on mental health stigma in Nepal. Our guiding questions for the review were:

(1) What are the causes or drivers of stigma related to mental disorders in Nepal?

(2) How is stigma related to mental disorders manifested at different levels, what behaviours, where, by whom and why?

(3) What approaches have been used to reduce stigma for mental health conditions, and what evidence supports these approaches?

Search and screening strategy

The databases searched included PsycINFO, Medline, Web of Science and NepJol (a Nepali database) and for a 20-year period from 1 January 2000 to 24 June 2020. Box 1 includes search terms used in all databases. As this is a sub-review of a broader scoping review of stigma for all health conditions in Nepal, the initial strategy used for the review included all health conditions and was not just restricted to mental health. Due to the limited search strategy that could be used in NepJol, only ‘Stigma’ was used as a search term. As a modification from the protocol, the search was repeated in PsycINFO, Medline and Web of Science with added terms for structural stigma. This was because during the data extraction phase, we noticed that we may have missed some literature given the vagueness in how ‘structural stigma’ is defined in existing literature. The same inclusion criteria applied, with the specification for mental health-related structural stigma and discrimination. See Box 2 for the inclusion criteria used. The review was registered through the Open Science Framework (OSF) (osf.io/u8jhn).

Box 1. Search terms used

Search terms used for stigma and health in international databases: Medline (n = 288), Web of Science (n = 407), PsycINFO (n = 96)

stigma* OR ‘stigma’ OR stereotyp* OR ‘stereotype’ OR prejudic* OR ‘prejudice’ OR discriminat* OR ‘discrimination’ OR ‘social perception’ OR ‘social distance’ OR ‘social stigma’) AND (Nepal* OR ‘Nepal’) AND (health condition terms)

Search terms used in Nepali data base: NepJol (n = 145)

‘Stigma’

Search terms used for structural stigma for all databases: Medline (n = 23), Web of Science (n = 59), PsycINFO (n = 14)

structur* OR ‘Institution’ OR system* OR ‘policy’ OR service*) AND (‘social discrimination’ OR ‘stigma’ OR barrier* OR ‘exclusion’ OR ‘inequity’ OR disparit*) AND (‘mental health’ OR ‘mental disorder’ OR ‘depression’ OR ‘mood disorder’ OR ‘anxiety’ OR ‘Schizophrenia’ OR ‘psychotic disorder’ OR ‘bipolar disorder’ OR ‘substance related disorder’) AND ‘Nepal’.

Box 2. Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for eligibility of searched texts:

(1) Articles published in English or Nepali only

(2) Articles published between 01/01/2000–06/24/2020

(3) Articles focused on Nepal as a geographical location (excludes studies carried out among Nepali population outside geographical area of Nepal such as Bhutanese refugees)

(4) Articles published in both Nepali and international peer-reviewed journals

(5) Relates to articles focused on stigma and its definitions such as discrimination, prejudice or stereotype

(6) Articles focused on stigma related to health conditions (excludes studies in other forms of stigma and discrimination such as gender and ethnicity and its effects on health outcomes)

(7) Includes data regardless of its ‘quality’ and study design

(8) Articles that include or mention at least one stigma-related outcome or domain

The title and abstract screening were completed by three reviewers (LW, DG and AP). The full-text screening was completed by one reviewer (LW) with 20% of the articles re-assessed for eligibility by two other reviewers (AP and DG). Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and additional review by the supervisor (BK). The screening was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O'Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, Macdonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tunçalp and Straus2018).

Data extraction and synthesis

Following the full-text screening, four authors (LW, DG, AP and MN) extracted information from the included articles using a framework developed by the authors (BK and SW). The framework covered key themes on stigma: (a) key stigma-related findings, (b) explanatory models, (c) characteristics of stigmatised groups, (d) myths, (e) ‘what matters most’, (f) locations and types of stigmatisation, (g) cultural norms and social interactions, (h) structural stigma, (i) impact of stigma and (j) recommended interventions. In addition, a separate sheet was created to extract information on any stigma-related interventions that were conducted or evaluated. The themes related to interventions included (a) intervention name, (b) type of intervention, (c) duration and (d) materials used.

After data extraction, DG collated the findings using narrative synthesis and shared them with the review team for inputs. Additionally, we conducted a quality review of 18 quantitative studies with stigma as primary outcome. We used the Systematic Assessment of Quality in Observational Research (SAQOR) tool with a modification for Cultural Psychiatric Epidemiology, SAQOR-CPE (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Grigoriadis, Mamisashvili, Koren, Steiner, Dennis, Cheung and Mousmanis2011; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Rasmussen, Kaiser, Haroz, Maharjan, Mutamba, de Jong and Hinton2014) to understand the scope and generalisability of the findings.

Results

Study selection

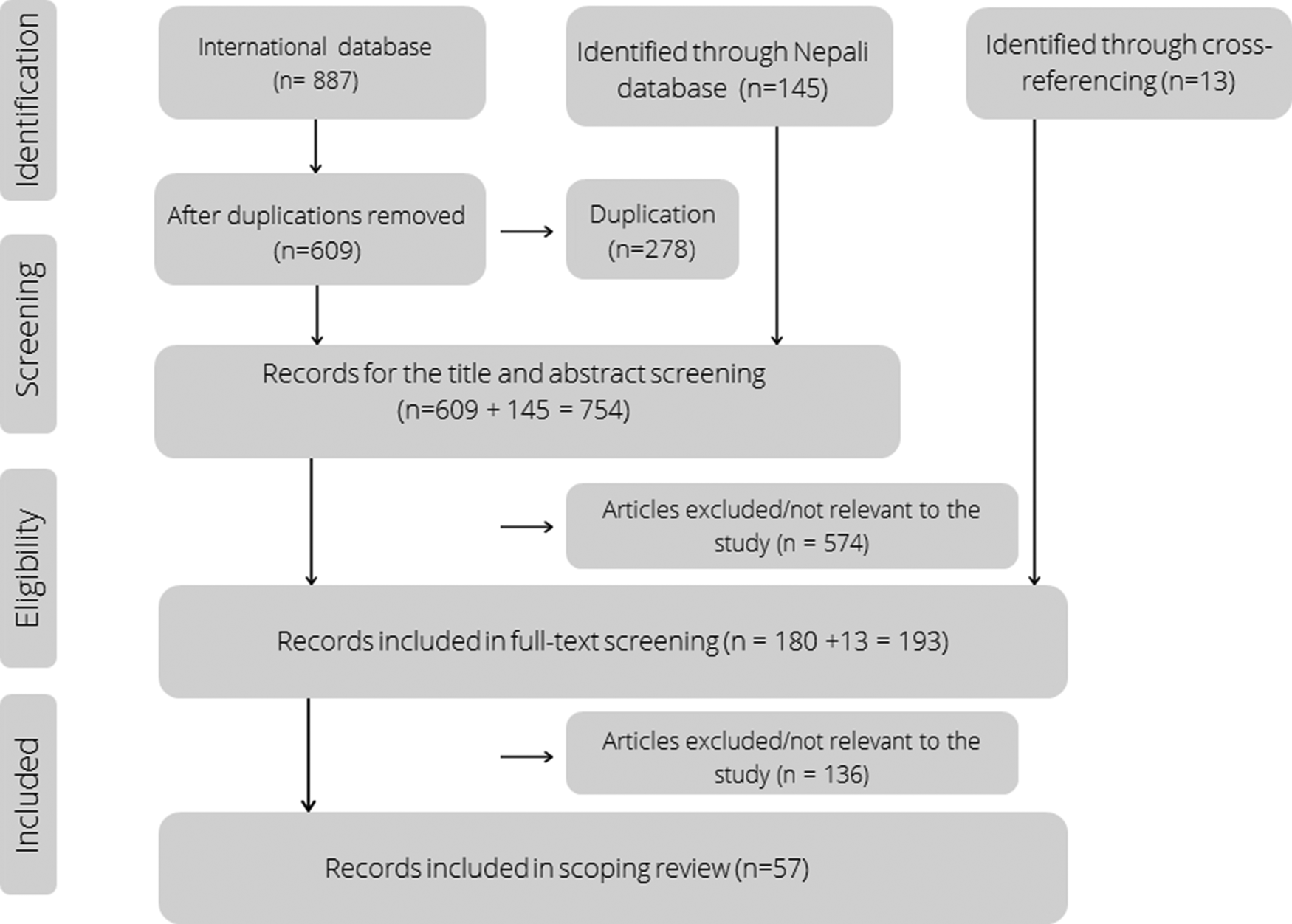

Figure 1 includes an overview of the search process. The search strategy for the international database resulted in 887 references, out of which 278 were duplicates. After removing duplicates, and adding 145 articles identified from the Nepali database, a total of 754 articles were included for the title and abstract screening. We removed 574 after the title and abstract screening because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. For full-text review, we added 13 articles identified through cross-referencing. We completed a full-text review for 193 articles and excluded 136 that did not meet the inclusion criteria or were of conditions other than mental disorders. A total of 57 articles were included in the study for data extraction and synthesis.

Fig. 1. PRISMA-ScR search strategy.

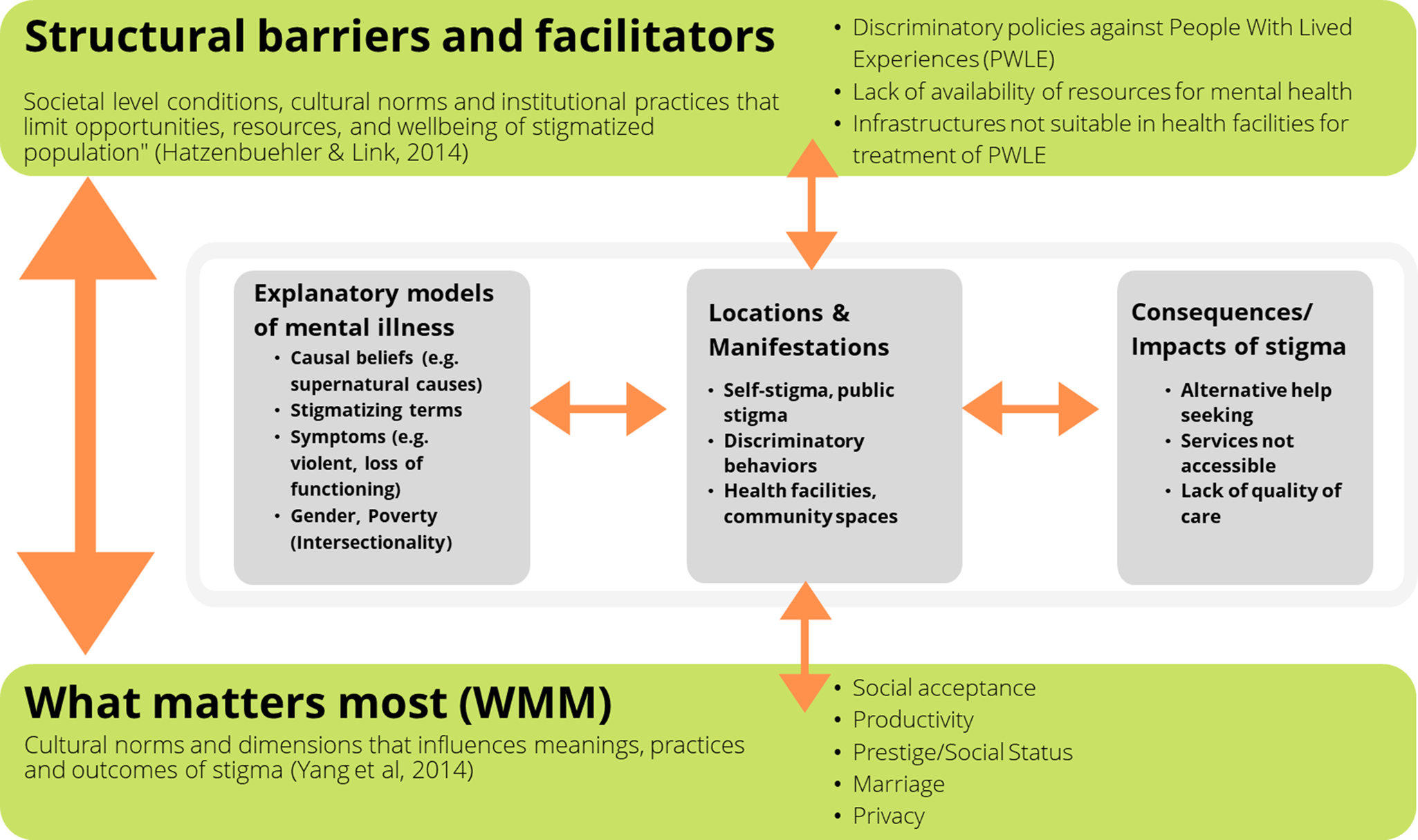

Table 1 gives an overview of the publications that were included in this review. Out of 57 studies included, 19 were quantitative, 19 were qualitative, nine were mixed methods, five were review articles (including literature reviews and scoping reviews), two were ethnographies, and three were other types of publications (including reports, opinion articles and protocols). The quality assessment of 18 relevant quantitative observational studies showed that only three were of ‘moderate quality’, while the remaining 15 were of ‘low-quality’. The main reasons for ‘low-quality’ were inadequacy in measurement quality (no mention of tool adaptation and validation in the local context), and sampling method (biased group not generalisable beyond research study and recruitment methods not well described). No articles were excluded after quality review. Hence, although we summarise the findings from these quantitative studies below, results need to be interpreted with caution because of the quality limitations.

Table 1. Overview of publications included in the scoping review

Most of the qualitative studies with stigma as the major theme or domain focused on public stigma of either general community members or healthcare workers. Quantitative or mixed methods studies predominantly focused on self or internalised stigma of people with lived experiences of mental disorders (PWLE) (Adhikari, Reference Adhikari2015; Neupane et al., Reference Neupane, Dhakal, Thapa, Bhandari and Mishra2016; Amatya et al., Reference Amatya, Chakrabortty, Khattri, Thapa and Ramesh2018; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Luitel and Jordans2018; Maharjan and Panthee, Reference Maharjan and Panthee2019; Shrestha, Reference Shrestha2019), public stigma (family and community members) (Neupane et al., Reference Neupane, Dhakal, Thapa, Bhandari and Mishra2016; Amatya et al., Reference Amatya, Chakrabortty, Khattri, Thapa and Ramesh2018; Koirala et al., Reference Koirala, Silwal, Gurung, Gurung and Paudel2019; Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Garman, Jordans and Lund2019; Pandey, Reference Pandey2019), health workers’ stigma (Gartoulla et al., Reference Gartoulla, Pantha and Pandey2015; Pathak and Montgomery, Reference Pathak and Montgomery2015; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Mutamba, Luitel, Gwaikolo, Onyango Mangen, Nakku, Rose, Cooper, Jordans and Baingana2018b, Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020), medical and pharmacy students’ stigma (Panthee et al., Reference Panthee, Panthee, Shakya, Panthee, Bhandari and Simon Bell2010; Adhikari, Reference Adhikari2018; Jalan, Reference Jalan2018; Shakya, Reference Shakya2018), and perceived stigma among PWLE and family members (Adhikari et al., Reference Adhikari, Pradhan and Sharma2008; Lamichhane, Reference Lamichhane2019). Four studies exclusively focused on courtesy stigma (Angermeyer et al., Reference Angermeyer, Schulze and Dietrich2003). Twenty publications focused on PWLE's experiences and their perceptions, of which two reported to have involved PWLE in the research and publication process (Drew et al., Reference Drew, Funk, Tang, Lamichhane, Chávez, Katontoka, Pathare, Lewis, Gostin and Saraceno2011; Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans2017) and two reported to have involved PWLE in the stigma reduction interventions (Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Gurung, Pokhrel, Adhikari and Komproe2018; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020) while the remaining had included PWLE as research participants.

The findings from the scoping review are collated into six broad themes related to stigma:

(1) ‘What matters most’: cultural factors that influence mental health stigma.

Although most studies did not explicitly explore the concept of ‘what matters most’, the theme was identified from the description of cultural contexts that shape stigma related to mental disorders in Nepal. Various studies discussed what mattered most to PWLE, their family members, the general community and health workers. Identified topics included social acceptance, productivity and income generation, social prestige and honour (ijjat), privacy or anonymity, marriage and equality.

For PWLE in Nepal, social acceptance and anonymity were described to matter the most (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020). This was reflected in their interest in engaging in productive activities, so they are looked upon as contributing members of society. Anonymity and privacy were primary concerns for PWLE and their families. Their concerns included privacy while visiting health facilities particularly because some PWLE were hiding their disorders from family and community members. Family members who could afford to take PWLE to India or big cities for treatment would do so due to fear of the community finding out about their disorders. This also resulted in PWLE not being willing to seek treatment or take medications because of potential discovery by family and community members. The greatest hesitation was related to seeking care in one's community and local health facilities.

Similar to PWLE, what mattered most for family and community members were productivity and economic contribution (Angdembe et al., Reference Angdembe, Kohrt, Jordans, Rimal and Luitel2017; Pandey, Reference Pandey2019). The community members felt that the biggest support for PWLE was their involvement in income-generating activities (Angdembe et al., Reference Angdembe, Kohrt, Jordans, Rimal and Luitel2017). In one of the studies (Pandey, Reference Pandey2019), the family members described financial burdens for taking care of PWLE and negative financial impacts on their professional lives. Family members mentioned losing prestige (Nepali: ijjat) in the society as an important cultural reason for not disclosing the diagnosis or seeking care (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008; Brenman et al., Reference Brenman, Luitel, Mall and Jordans2014). Another reason, especially for parents of PWLE, was not being able to marry off their children as a result of mental illness, particularly for daughters. Not being able to marry off one's daughter was considered one of the biggest cultural burdens for parents in Nepal, which is further amplified by the myth that marriage would heal mental disorders (Brenman et al., Reference Brenman, Luitel, Mall and Jordans2014).

For the health workers, what mattered most were the structures required for delivering quality mental health care. Health workers reported physical threat (possibility of personal harm and experiencing violence while treating PWLE), loss of social prestige in the community for treating PWLE, and lack of professional knowledge and competence (how to treat illness) as the most important to them (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020). Several publications reported public and health workers’ perceptions of PWLE as violent and aggressive people who can damage property and harm themselves or others. Thus, fear of harm or danger was a prominent driver of mental disorders stigma among health workers in Nepal (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008; Neupane et al., Reference Neupane, Dhakal, Thapa, Bhandari and Mishra2016; Mahato et al., Reference Mahato, van Teijlingen, Simkhada, Angell, Ireland, Maharjan Preeti Mahato, Devkota, Fanning, Simkhada, Sherchan, Silwal, Maharjan, Maharjan and Douglas2018; Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Regmi, Gurung, Luitel, Petersen, Jordans and Komproe2020).

For the handful of PWLE working as advocates in Nepal, what mattered most focused on equality in decision making regarding policies (Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans2017; Koirala et al., Reference Koirala, Silwal, Gurung, Gurung and Paudel2019). They expressed a sense of frustration for not having equal rights or not being taken seriously in decision-making processes.

(2) Structural facilitators and barriers (structural stigma)

Although structural forms of stigma were not directly reported in any of the publications, many studies (13 of 57) reported structural barriers and facilitators that perpetuated mental disorders stigma or contributed to the treatment gap. Lack of mental health-related policies and strategies, adequate allocation of budget, and issues in supply of medicines were some of the frequently reported barriers.

Studies cited low political will to prioritise mental health services that resulted in the lack of supportive mental health policies and strategies (Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Kohrt, Rathod and Komproe2017; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marais, Abdulmalik, Ahuja, Alem, Chisholm, Egbe, Gureje, Hanlon, Lund, Shidhaye, Jordans, Kigozi, Mugisha, Upadhaya and Thornicroft2017). The situation was further aggravated by discriminatory policies such as those encouraging imprisonment and forcibly initiating treatment that violated the rights of PWLE (Drew et al., Reference Drew, Funk, Tang, Lamichhane, Chávez, Katontoka, Pathare, Lewis, Gostin and Saraceno2011). Another policy-level barrier was the vagueness of suicide policies that led to public misunderstanding of suicide as illegal in Nepal (Hagaman et al., Reference Hagaman, Maharjan and Kohrt2016; Ramaiya et al., Reference Ramaiya, Fiorillo, Regmi, Robins and Kohrt2017). This led to under-reporting of suicides, which hampers accurate data collection and programme planning (Hagaman et al., Reference Hagaman, Maharjan and Kohrt2016). Another policy-level challenge to reporting is the lack of mental disorder-related indicators in government-level health reporting. Under-reporting of mental disorders negatively influenced the government resource management during the 2015 earthquake in Nepal (KC et al., Reference KC, Gan and Dwirahmadi2019). The disaster risk reduction and management plans did not include mental health care packages resulting in the massive rise of cases post-earthquake that were almost exclusively addressed through international/national non-government organisations’ effort (KC et al., Reference KC, Gan and Dwirahmadi2019). A key barrier to developing and implementing inclusive mental health policies was poor involvement of PWLE in the policy-making process. The long-standing structural hierarchy and power dynamics between service providers and PWLE as noted by many advocates made it difficult for PWLE to actively participate in planning and decision-making process (Lempp et al., Reference Lempp, Abayneh, Gurung, Kola, Abdulmalik, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Alem, Thornicroft and Hanlon2018). This was also cited as the main reason behind systematic marginalisation of PWLE within the policy-making and other health systems processes (Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans2017).

In terms of programme planning, mental health was not as prioritised as other sectors (e.g. maternal health) where the most budget was allocated (Upadhyaya, Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Pokhrel, Gurung, Adhikari, Petersen and Komproe2014). This led to inadequate mental health-related training and lack of supervision for primary healthcare providers. Another important structural challenge was an inadequate supply of psychiatric medications. Health workers also pointed out how there was a lack of referral mechanisms and private rooms for counselling that reduced health workers’ motivation to treat patients with mental disorders (Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Kohrt, Rathod and Komproe2017; Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Gurung, Pokhrel, Adhikari and Komproe2018, Reference Upadhaya, Regmi, Gurung, Luitel, Petersen, Jordans and Komproe2020; Lamichhane, Reference Lamichhane2019). Health professionals were also concerned about being stigmatised for choosing ‘psychiatry’ or ‘mental health’ as a specialty which led to a lack of mental health specialists in Nepal (Hagaman et al., Reference Hagaman, Khadka, Wutich, Lohani and Kohrt2018). Even for those interested in specializing in mental health, the coursework had a strong focus on biomedical treatment and use of drugs, with a lack of alternative treatment such as psychotherapies and counselling (Subedi, Reference Subedi2011).

(3) Explanatory models of mental disorders

The terminology used for mental disorders and the explanatory models invoked by community members and health workers perpetuated stigma against PWLE. Regarding explanatory models, the most perceived causes included supernatural forces, curses, sinful behaviour, improper rituals or cultural practices and witchcraft. Bad karma (negative effects of past misdeeds including prior lives) or bhagya (fate) that prompted stigma towards PWLE (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008; Subedi, Reference Subedi2011; Kisa et al., Reference Kisa, Baingana, Kajungu, Mangen, Angdembe, Gwaikolo and Cooper2016; Angdembe et al., Reference Angdembe, Kohrt, Jordans, Rimal and Luitel2017). This led to the labelling of PWLE as abhagi (unlucky or ill-fated) or paapi (sinful persons). The general public also perceived mental disorders to be hereditary, which extended the use of these terms when describing the entire family such that anyone in the family of PWLE would be labelled with derogatory terminology (Subedi, Reference Subedi2011). Similarly, common symptoms of mental disorders as reported in several studies were exhibiting violent behaviour, being dishevelled, roaming around the road aimlessly, not taking care of personal hygiene, laughing spontaneously and not being able to do given tasks; these beliefs amplified the negative perceptions towards PWLE and increased stigma (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020; Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Regmi, Gurung, Luitel, Petersen, Jordans and Komproe2020).

Another belief was that mental disorders were incurable. Health workers reported that mental disorders were life-long conditions that had no effective treatment. The general public stated that mental disorders could not be cured by Western biomedicine but only through traditional healing (Kisa et al., Reference Kisa, Baingana, Kajungu, Mangen, Angdembe, Gwaikolo and Cooper2016; Simkhada et al., Reference Simkhada, Sharma, Pradhan, Van Teijlingen, Ireland, Simkhada and Devkota2016; Koirala et al., Reference Koirala, Silwal, Gurung, Gurung and Paudel2019; Lamichhane, Reference Lamichhane2019; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020). This was also reflected in conceptions about the use of psychotropic medications for mental health conditions; most people described that once a person starts taking medications, she/he must take it for life (Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Gurung, Pokhrel, Adhikari and Komproe2018). Some studies reported public views that mental disorders are contagious and can be spread through touch. Similarly, an ethnographic study (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008) described how Nepali community differentiated mental disorders as dysfunctions of ‘brain-mind’ (dimaag) while psychosocial distress as that of ‘heart-mind’ (man) and how the mental disorders and dysfunction of ‘brain-mind’ were more stigmatised as it was associated with lack of behavioural control, inability to abide by social norms and more likely to be permanent compared to transient distress associated with problems in the ‘heart-mind’.

Community members, sometimes even health workers, labelled PWLEs with stigmatizing terms such as paagal/baulaahaa (mad/crazy), taar khuskeko (loose wire), dimaag nabhayeko (no brain-mind), bokshi laageko (afflicted by witchcraft), paapi/paap ko bhogi (sinful), khusket (someone whose mind has become lose), dimaag crack bhayeko (one whose brain-mind has cracked) (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008; Kisa et al., Reference Kisa, Baingana, Kajungu, Mangen, Angdembe, Gwaikolo and Cooper2016; Angdembe et al., Reference Angdembe, Kohrt, Jordans, Rimal and Luitel2017; Lempp et al., Reference Lempp, Abayneh, Gurung, Kola, Abdulmalik, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Alem, Thornicroft and Hanlon2018; Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Regmi, Gurung, Luitel, Petersen, Jordans and Komproe2020). Such stigmatizing terms were mostly used towards people with low socio-economic conditions such as Dalits (low caste groups, historically referred to as untouchables), women, widows and other minorities (Mahato et al., Reference Mahato, van Teijlingen, Simkhada, Angell, Ireland, Maharjan Preeti Mahato, Devkota, Fanning, Simkhada, Sherchan, Silwal, Maharjan, Maharjan and Douglas2018); this highlights the intersectionality of the perception of mental disorders with female gender, marginalised ethnicities and persons of low socio-economic status. The public perceived that PWLE, especially women, showed symptoms such as talking incessantly, and should be isolated from society (Mahato et al., Reference Mahato, van Teijlingen, Simkhada, Angell, Ireland, Maharjan Preeti Mahato, Devkota, Fanning, Simkhada, Sherchan, Silwal, Maharjan, Maharjan and Douglas2018). A study carried out among caregivers and relatives of PWLE reported higher correlates of negative attitudes toward mental disorders if PWLE had low education status and were females (Neupane et al., Reference Neupane, Dhakal, Thapa, Bhandari and Mishra2016).

(4) Manifestations of stigma and locations of discrimination

The review identified a number of manifestations of mental disorders. Studies reported the prevalence of self-stigma ranging from 34 to 54% of patients in psychiatric Outpatient Department (OPD) of national hospitals, and 80% of persons screening positive for alcohol use disorder in the community reported internalised stigma (Amatya et al., Reference Amatya, Chakrabortty, Khattri, Thapa and Ramesh2018; Maharjan and Panthee, Reference Maharjan and Panthee2019; Shrestha, Reference Shrestha2019). The patients scored high on components such as stereotype endorsement, discrimination experience and social withdrawal. Similarly, family members reported high perceived stigma (52.2%) including the perception that PWLE were violent and burdensome financially (Pandey, Reference Pandey2019), and needed the same kind of discipline and control as a young child (Neupane et al., Reference Neupane, Dhakal, Thapa, Bhandari and Mishra2016). PWLE reported feeling rejected by family members (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Luitel, Tomlinson and Komproe2013). More than 50% slightly or strongly agreed to being avoided by others, asked to resign from work and neglected by health professionals (Adhikari et al., Reference Adhikari, Pradhan and Sharma2008). Several studies also reported how PWLE are isolated in the communities, often avoided and considered ineligible to take part in social activities and festivities (Kisa et al., Reference Kisa, Baingana, Kajungu, Mangen, Angdembe, Gwaikolo and Cooper2016; Lamichhane, Reference Lamichhane2019). PWLE are also considered ineligible for work or marriage and even if they do get married, mental disorders are considered acceptable grounds for divorce (Drew et al., Reference Drew, Funk, Tang, Lamichhane, Chávez, Katontoka, Pathare, Lewis, Gostin and Saraceno2011; Hagaman et al., Reference Hagaman, Khadka, Wutich, Lohani and Kohrt2018). High levels of perceived stigma were reported among patients in the context of marriage, such as having their opinions taken less seriously, feeling of being looked down upon and feeling of being treated as less intelligent or as a failure.

Advocates for PWLE reported explicit discrimination from stakeholders in policy-making or decision-making processes via exclusion or tokenistic involvement (Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans2017; Lempp et al., Reference Lempp, Abayneh, Gurung, Kola, Abdulmalik, Evans-Lacko, Semrau, Alem, Thornicroft and Hanlon2018). Human rights abuses were mentioned in some publications where the PWLEs were subjected to violence by the community members and chained/locked up by the family members. Hence, the locations of stigma mostly reported by the studies were home, community or social setting, and healthcare settings (Angdembe et al., Reference Angdembe, Kohrt, Jordans, Rimal and Luitel2017).

(5) Consequences and impacts of stigma

The studies reported consequences and impacts of mental disorders stigma, which included low help-seeking behaviour, treatment non-adherence, concealment of disorders, poor resource allocation and poor engagement of PWLE (Regmi et al., Reference Regmi, Pokharel, Ojha, Pradhan and Chapagain2004; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Luitel, Tomlinson and Komproe2013; Upadhyaya, Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Pokhrel, Gurung, Adhikari, Petersen and Komproe2014; Adhikari, Reference Adhikari2015).

Studies overall reported poor help-seeking behaviour among PWLE and their families. Even among those seeking treatment, studies reported low medication adherence among PWLE (Adhikari, Reference Adhikari2015; Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Gurung, Pokhrel, Adhikari and Komproe2018, Reference Upadhaya, Regmi, Gurung, Luitel, Petersen, Jordans and Komproe2020). The belief that mental disorders are incurable was linked to non-adherence (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Luitel, Tomlinson and Komproe2013) and the use of alternative treatments such as traditional healing (Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Adhikari, Upadhaya, Hanlon, Lund and Komproe2015; Kisa et al., Reference Kisa, Baingana, Kajungu, Mangen, Angdembe, Gwaikolo and Cooper2016; Angdembe et al., Reference Angdembe, Kohrt, Jordans, Rimal and Luitel2017; Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Pokhrel, Gurung, Adhikari, Petersen and Komproe2017; Lamichhane, Reference Lamichhane2019). Studies reported that idioms of distress in Nepal focused mainly on physical symptoms such as gyastrik (a Nepali idiom encompassing both gastritis and psychological distress) which made it difficult to identify mental disorders (Kohrt and Hruschka, Reference Kohrt and Hruschka2010). Similarly, families often registered PWLE under false names in health facilities, which later created problems in continuity of care and follow-up (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020). Low help-seeking behaviour also contributed to reduced demand for mental health services in health facilities which then impacted resource allocation and supply in procurement and policies (Upadhaya et al., Reference Upadhaya, Jordans, Gurung, Pokhrel, Adhikari and Komproe2018). A major consequence of concealment of illness by PWLE and families was disruption in the involvement of PWLE and family members in stigma reduction activities, advocacy and health systems strengthening processes because such engagement typically relies on disclosure of mental disorders to the community (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Jordans, Regmi and Sharma2005; Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Upadhyaya, Magar, Giri, Hanlon and Jordans2017; Rai et al., Reference Rai, Gurung, Kaiser, Sikkema, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Tergesen and Kohrt2018).

(6) Measures and interventions

Our review identified only nine standard stigma measures used in quantitative and mixed-methods studies. The tools assessed self and internalised stigma with the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) and Self-stigma of Mental Illness (SSMIS); public stigma with the Community Attitude towards Mental Illness (CAMI), public stigma scale (PSS), and Social Distance Scale (SDS); clinician's attitudes with the Mental Illness Clinician's Attitudes (MICA), mhGAP attitude scale and Attitude Scale for Mental Illness (ASMI); and stigma-related barriers to care with the Barriers to Access to Care (BACE). Five of the studies reported development of their own tool, either by generating new items, or consolidating items from multiple tools (Adhikari et al., Reference Adhikari, Pradhan and Sharma2008; Gartoulla et al., Reference Gartoulla, Pantha and Pandey2015; Pathak and Montgomery, Reference Pathak and Montgomery2015; Shakya, Reference Shakya2018; Koirala et al., Reference Koirala, Silwal, Gurung, Gurung and Paudel2019). Although ISMI was the most popular tool (n = 4 studies) to measure internalised stigma in Nepal, only one study reported a translation and adaptation process and reported tool reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.87) (Shrestha, Reference Shrestha2019). Studies using the SSMIS reported varying item numbers. The translation and adaptation process were reported for other measures except ASMI, CAMI and PSS. However, the studies did not report reliability or validity scores.

Only four of the reviewed publications mentioned implementation and evaluation of interventions to reduce mental disorder-related stigma in Nepal (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Sikkema, Luitel, Rai, Singla, Lamichhane, Lund and Patel2018a, Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020; Rai et al., Reference Rai, Gurung, Kaiser, Sikkema, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Tergesen and Kohrt2018; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Varma, Carpenter-Song, Sareff, Rai and Kohrt2020). All four publications addressed the same intervention: REducing Stigma among HealthcAre ProvidErs (RESHAPE), which was explicitly designed using a ‘what matters most’ framework (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020). The intervention embedded anti-stigma components such as myth-busting, PWLE recovery narrative through a PhotoVoice technique, and aspirational figures within the mhGAP training of primary healthcare workers in Chitwan District to reduce their stigma attitudes and improve competencies.

Discussion

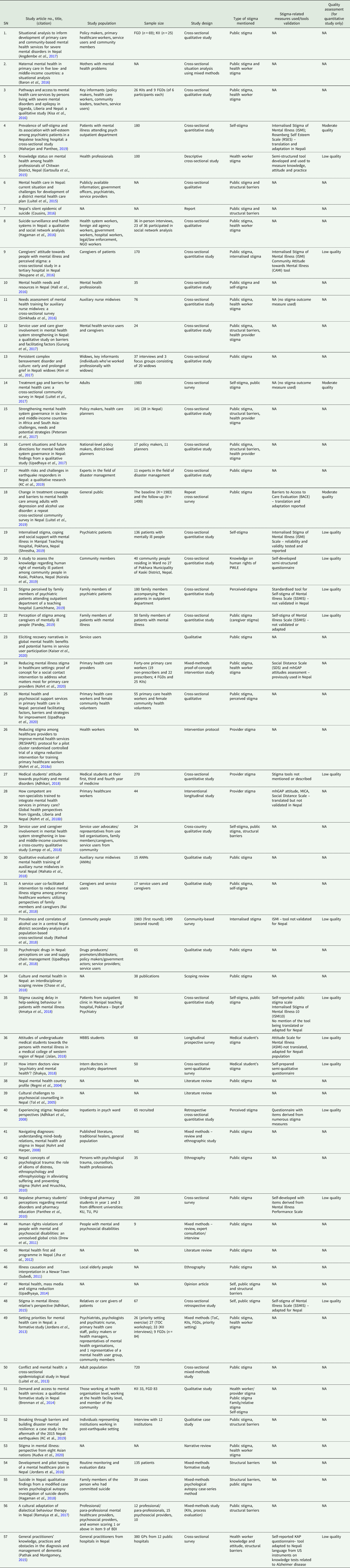

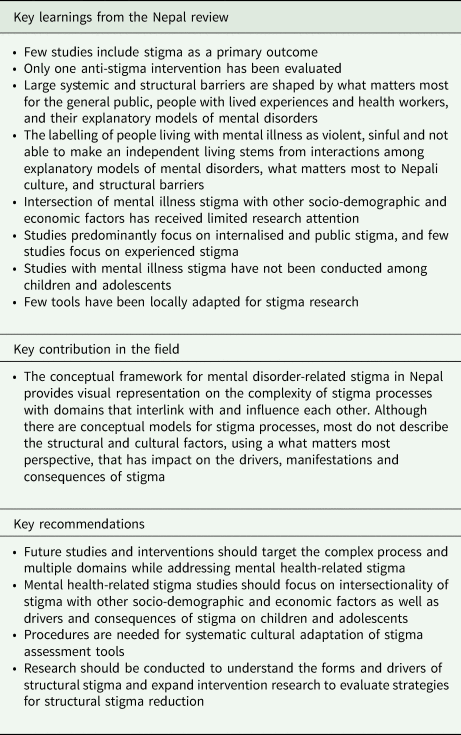

Our scoping review identified a modest number of publications on stigma and discrimination related to mental disorders in Nepal (n = 57) from 2000 through 2020. The studies focused on a range of stigma types (internalised, perceived, public, courtesy, practitioner and medical students' stigma) and used diverse methods (quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, ethnography) to understand stigma. However, few studies had mental health stigma as their primary outcome or domain. Additionally, most quantitative studies were conducted in specific populations and were of poor methodological quality and used measures that were not culturally adapted to the population under study. The stigma-related information and findings from these studies were extracted and collated under the themes of: (1) what matters most; (2) structural facilitators and barriers; (3) drivers and markers of stigma; (4) manifestations and locations; (5) consequences and impacts; and (6) measures and interventions. These themes are summarised and mapped into a conceptual framework (Fig. 2). This framework helps to understand the stigma processes in Nepal and also to identify the gaps in literature and the areas/domains where further interventions can be planned to help reduce mental health-related stigma in Nepal. The key findings, recommendations and contribution to the field are summarised in Table 2.

Fig. 2. Conceptual framework for mental disorder-related stigma in Nepal.

Table 2. Key learnings, contribution to the field and recommendations for stigma research in Nepal

Structural barriers identified in our review included lack of mental health policies, low budgeting for mental healthcare, lack of trained human resources in primary healthcare settings and lack of medications. As shown in the conceptual framework, these structural barriers, and ‘what matters most’ for people in Nepali culture, interact with each other to influence the stigma processes such as stigma drivers, its manifestations and impacts. This influence of what matters most to cultures and structural barriers on stigma has also been highlighted by Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Chen, Sia, Lam, Lam, Ngo, Lee, Kleinman and Good2014a, Reference Yang, Thornicroft, Alvarado, Vega and Link2014b). An example of this interaction is how what matters most to health workers can be influenced by availability of resources. For instance, if there is a scarcity of medications for the treatment of mental disorders, then health workers would prioritise conditions where resources are easily available. Similarly, if what matters most to the public is productivity then these attitudes will be reflected in policies, where less productive people experience structural discrimination.

The explanatory models of mental disorders including causal beliefs and symptoms and markers of stigma in Nepal are similarly influenced by these domains of what matters most and structural barriers and facilitators. Conflicts between the explanatory models of mental disorders such as perceived causes and symptoms, and what matters most to Nepali culture, exacerbated by the structural barriers may lead to marking of PWLE as being violent, sinful or not being able to make an independent living. This in turn manifests into various human rights abuses such as being chained or locked-up, discrimination in health facilities, refusals in marriage proposals and exclusion of PWLE in community or religious activities. These stigma manifestations related to mental disorders appear to be heightened when it intersects with other forms of drivers and markers such as gender, ethnicity and socio-economic conditions in Nepal. Women, widows, Dalits and people living in poverty were identified to face more stigma in Nepal.

Another example of the interactions between the domains can be seen in how suicide is perceived by the culture (sin) and is reflected in policies (an illegal act), which has then shaped how people who attempt suicide are perceived as sinful or criminal (drivers and markers) (Hagaman et al., Reference Hagaman, Maharjan and Kohrt2016, Reference Hagaman, Khadka, Wutich, Lohani and Kohrt2018). This is reported to manifest as internalised stigma and public stigma where such people perceive themselves as weak-minded with reduced potential for marriage. This leads to them not seeking or adhering to treatments (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Luitel, Tomlinson and Komproe2013).

The conceptual framework describes how the domains interact with each other to shape and reshape stigma processes. It also helps suggest pathways to design interventions that may reduce mental health-related stigma by breaking these processes. As causal beliefs of mental disorders, lack of awareness, fear of harm or burden are some of the key drivers, interventions could target these drivers through myth-busting exercises, awareness campaigns and education-based interventions. Interventions such as RESHAPE (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Sikkema, Luitel, Rai, Singla, Lamichhane, Lund and Patel2018a, Reference Kohrt, Turner, Rai, Bhardwaj, Sikkema, Adelekun, Dhakal, Luitel, Lund, Patel and Jordans2020) address what matters most to PWLE and the drivers of stigma among health workers through contact, myth-busting and recovery narratives (Rai et al., Reference Rai, Gurung, Kaiser, Sikkema, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Tergesen and Kohrt2018). Other interventions may focus on the intersectionality that exacerbates stigma or tackle what matters most to the public by focusing on productivity or livelihoods. Studies have shown benefits of stigma interventions targeting multiple stakeholders and multiple domains (Richman and Hatzenbuehler, Reference Richman and Hatzenbuehler2014; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Elshafei, Nguyen, Hatzenbuehler, Frey and Go2019). Currently, only one stigma intervention (RESHAPE) was identified through the review which points to a glaring gap in the mental health-related stigma field in Nepal. Since the time of the review, there have been more recent studies of stigma interventions in Nepal. A recent publication on the RESHAPE intervention demonstrated that stigma reduction not only contributed to improved attitudes over 16-month period, it was also associated with improved accuracy of clinical diagnoses (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Turner, Rai, Gurung, Dhakal, Bhardwaj, Lamichhane, Singla, Lund, Patel, Luitel and Sikkema2021). Another recent study, which used video-based recovery testimonials from PWLE, showed that stigma attitudes reduced with testimonials about depression but stigma increased with video testimonials about psychosis (Tergesen et al., Reference Tergesen, Gurung, Dhungana, Risal, Basel, Tamrakar, Amatya, Park and Kohrt2021).

Another gap in the literature identified in the review is a sparse understanding of the mechanisms of how mental illness stigma intersects with other socio-demographic and economic factors. Also, there is limited knowledge on the impact of stigma related to mental disorders on PWLE, family members and the larger public outside the health system. The structural barriers and stigma have an overarching influence on other domains of stigma processes. Therefore, structural barriers, indicators to measure the structural barrier and discrimination and interventions to reduce structural barriers need to be explored further.

Similarly, the review revealed a focus mainly on internalised and public stigma. More studies need to be conducted to explore the anticipated and experienced stigma by PWLE and caregivers, especially in contexts such as the workspace, educational institutions, health facilities and other religious or community organisations. For example, a recent multi-country study conducted after the review period found that in many LMICs, PWLE had low expectations of how they would be treated by health workers and therefore they did not consider the experiences discriminatory, e.g. ‘this is how we expect to be treated’ (Koschorke et al., Reference Koschorke, Oexle, Ouali, Cherian, Deepika, Mendon, Gurung, Kondratova, Muller, Lanfredi, Lasalvia, Bodrogi, Nyulászi, Tomasini, El Chammay, Abi Hana, Zgueb, Nacef, Heim, Aeschlimann, Souraya, Milenova, van Ginneken, Thornicroft and Kohrt2021). No publications were identified that focused on the mental health stigma and discrimination among children and adolescents, although a number of studies have explored the role of other forms of stigma (e.g. gender and caste discrimination, discrimination against former child soldiers) on poor mental health outcomes (Kohrt and Maharjan, Reference Kohrt and Maharjan2009; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Tol, Perera, Karki, Koirala and Upadhaya2010; Morley and Kohrt, Reference Morley and Kohrt2013; Kohrt and Bourey, Reference Kohrt and Bourey2016) and social attitudes influencing what is labelled as mental illness among children (Burkey et al., Reference Burkey, Ghimire, Adhikari, Wissow, Jordans and Kohrt2016; Langer et al., Reference Langer, Ramos, Ghimire, Rai, Kohrt and Burkey2019).

Another area where the review revealed paucity in information was measures of mental disorder-related stigma. Only nine stigma tools were reported across studies and most did not provide details on adaptation and measures of reliability/validity. Studies need to identify indicators that are most relevant to Nepali context and what matters most in Nepal to capture the stigma processes and evaluate the effectiveness of stigma interventions. Along with the measures, evaluation methods need to be diversified with intervention and longitudinal studies.

Finally, as the studies report on stigma and discrimination of PWLE, the researchers must be mindful of PWLE's dynamics and influences in the discourse. PWLE led movements have highlighted the need for their involvement in all aspects of intellectual and decision-making processes including research with slogans such as ‘Nothing about us without us’ (Charlton, Reference Charlton1998). Only a few of the articles in the review reported involving PWLE and caregivers in the research and publication process, while most of the studies limited the roles of PWLE to research participants. This in itself reflects the systemic marginalisation and discrimination of PWLE within the research and academic field. Hence, future mental health research, especially in the area of stigma and discrimination, should focus on the roles and process of effective involvement of PWLE to help enhance the findings and make it more relevant. Another issue to consider is who is leading mental health research in Nepal. A recent review of mental health research publications found that only 23% were led by Nepali women, and only 15% were led by researchers from Nepali ethnic minorities or low caste groups (Gurung et al., Reference Gurung, Sangraula, Subba, Poudyal, Mishra and Kohrt2021). This is a notable under-representation of persons from stigmatised groups in Nepal leading research on stigma. A change in who conducts research about stigma is likely to impact what is learned about stigma and how to effectively reduce its detrimental impacts.

Limitations

We acknowledge a number of limitations of this scoping review. The qualitative coding process is inherently subjective. We have however tried to reduce some of the subjectivity through the involvement of multiple reviewers and discussion with senior researchers, including discussion of results with a co-author who is PWLE. We were also limited to conducting quality assessments of only quantitative studies and no studies were excluded due to low methodological quality. This decision was made as the major objective of this review was to explore existing stigma-related knowledge and information, rather than quality assessment. However, some quantitative studies had serious methodological flaws that we wanted to point out for the generalisability of the findings and for future studies. Similarly, despite our comprehensive search strategy, we acknowledge that the search terms may not have been exhaustive. Another limitation was that the study did not include approximately the past 12 months of publications. As with any review, there might have been new publications that may have come out after the review process and have not been included in this review. We have tried to address this in the discussion by including notable recent publications related to stigma. A final limitation is that our presentation of results and discussion did not account for change over time. From a popular media perspective, health professional education curricula, mental health training initiatives in primary care and community settingsand major events impacting mental health, such as the 2015 earthquakes and recent COVID-19 pandemic, there are several factors that have likely influenced changes in attitudes over time. Because our review predominantly summarised content qualitatively, we are unable to conclude whether there have been significant changes over the past 20 years.

Conclusion

In this study, we highlight what matters most to key stakeholders regarding stigma related to mental disorders. Additionally, we summarised how mental disorders were explained, discussed and recognised in the community as documented in peer-reviewed journal publications in the past 20 years. We also highlighted several structural barriers that further aggravated mental health stigma in Nepal. As stigma processes are complex and interlinked, more studies are required to understand this complexity and establish effective interventions targeting multiple domains. Future stigma research should clarify what conceptual models can inform study design and interpretation. There is a need to develop procedures for systematic cultural adaptation of stigma assessment tools. Research should be conducted to understand the forms and drivers of structural stigma and expand intervention research to evaluate strategies for stigma reduction. Finally, greater opportunities for researchers with lived experience of mental illness and researchers from stigmatised groups are needed to guide the science of tackling stigma in Nepal.

Data

Additional data and materials related to the scoping review are available from the corresponding author dristy.1.gurung@kcl.ac.uk.

Financial support

DG and BAK have received funding from the US National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH111280, R01MH120649). AP has received support from the NIMH T32 on Social Determinants of HIV (T32MH128395-01). GT is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London at King's College London NHS Foundation Trust, and by the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award. GT also receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). GT is supported by the UK Medical Research Council as a principal investigator of the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIMH, NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.