Introduction

Latin America, consisting of 33 countries or territories, has had the second-highest amount of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases and deaths per capita (Burki, Reference Burki2020; World Health Organization, 2020; Ríos, Reference Ríos2021). Latin America is vulnerable to the destructive outbreak for several reasons including long-standing structural and socioeconomic inequities (Carvalho et al., Reference Carvalho, Santos, Melo, Gurgel and Oliveira2015; Dávila-Cervantes and Agudelo-Botero, Reference Dávila-Cervantes and Agudelo-Botero2019; Burki, Reference Burki2020) over 20% of the population in poverty, lack of healthcare access, underfunded healthcare systems, poor governance or political dynamics, a high burden of chronic and metabolic health conditions and lack of preparedness to fight the pandemic (Malta et al., Reference Malta, Murray, Da Silva and Strathdee2020). Reportedly, there is a considerable increase in psychological morbidities among several demographic groups, including healthcare workers, the general population and students (Campos et al., Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, de Fátima Valadão-Dias and Marôco2021b). Latin America is a vast area where tropical regions span across almost all countries and regional disparities on mental health have been reported (Malta et al., Reference Malta, Murray, Da Silva and Strathdee2020), but we still lack evidence on the prevalence of mental health symptoms as well as their heterogeneities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Recently, meta-analyses have provided early global evidence on the prevalence of mental health symptoms across groups, including healthcare workers, the general population and students (Batra et al., Reference Batra, Singh, Sharma, Batra and Schvaneveldt2020; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Guo, Yu, Jiang and Wang2020; Pappa et al., Reference Pappa, Ntella, Giannakas, Giannakoulis, Papoutsi and Katsaounou2020). These reports included very few studies based on Latin American samples. With emerging studies on mental health in Latin America, it is critical to synthesise meta-analytical evidence to provide integrated data on mental health among key demographic groups in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to investigate the pooled prevalence of mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among frontline healthcare workers, general healthcare workers, the general population and university students in Latin America. We first perform subgroup analysis for Latin America based on South America (a majority but not all countries are in tropical regions) and Central America (all countries are entirely tropical).

Methods

Protocol registration

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement 2020 (Liberati et al., Reference Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, Mulrow, Gøtzsche, Ioannidis, Clarke, Devereaux, Kleijnen and Moher2009) to guide our meta-analysis and registered it with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020224458).

Eligibility criteria

The search targeted observational studies that assessed the prevalence of psycho-morbid symptoms of anxiety, depression, distress and insomnia among frontline healthcare workers, general healthcare workers, the general population aged 18 years or above and university students in Latin America. A priori inclusion criteria were established to identify eligible studies that used established psychometric survey tools, used the English language, and were available as full-texts. Studies that targeted other populations, including children, adolescents and certain subgroups (e.g., pregnant women), were excluded. Other study designs, such as reviews and meta-analyses, qualitative, mixed methods, case reports, studies published only as abstracts, biochemical and experimental studies, or articles lacking the use of robust psychometric instruments or with an ambiguous methodology to identify prevalence were also excluded. Studies based on non-Latin American countries were excluded. Studies with unclear methodology and results were reviewed carefully, and a researcher (WX) attempted to contact authors to seek the information in several instances: (1) if the study reported estimates for both targeted and excluded populations, posing challenges for us to delineate the prevalence rate for the population of interest to our study; (2) if the study did not report the prevalence as proportions; (3) if the study did not specify cut-off scores for levels of severity; or (4) if the study was missing crucial information such as response rate, duration of data collection and gender distribution.

Data sources and search strategy

This meta-analysis is part of a large project on meta-analysis of mental health symptoms during COVID-19. Bibliographic databases, such as PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO and Web of Science, were searched on 13 August 2021. medRxiv was also searched for preprints. Search algorithms specific to each database were used to yield a comprehensive pool of literature. A detailed search strategy appears in online Supplementary Table S1.

Phases of screening

A researcher (JC) exported the search results from various databases into Endnote to remove duplicates and then imported them into Rayyan for subsequent screening. Two reviewers (AD & BZC) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all papers in accordance with the prespecified eligibility criteria. The eligible abstracts proceeded to full-text screening for possible inclusion. Any conflicts between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (RKD).

Data extraction

A codebook was developed for standardisation and consistency. The final studies included from the screening process were sent to three groups (two reviewers in each group, WX & AY, BZC & AD, RZC & SM) for thorough investigation and extraction of relevant data elements into a coding book. Standardised codes were used to record pertinent variables, including author, title, country, duration of data collection, study design, population, sample size, response rate, female proportion, mean age, psychological outcome, severity level of outcome, type of survey instruments with cut-off scores and prevalence of psycho-morbid events. The severity of psychological outcomes of interest was coded as above mild, moderate above and severe levels (if available). The studies that reported only mild, moderate, and severe prevalence data were recoded into mild above, moderate above and severe prevalence for consistency purposes. The severity levels in studies that only reported the overall prevalence were determined based on cut-off scores (if available). After finishing independent coding, all the extracted data elements were subject to a second round of review by the coders to identify any discrepancies. In case of disagreements, a third reviewer (WX or TL) helped to achieve consensus through re-verification and discussion.

Risk of bias (RoB) assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) with seven questions was used as a quality assessment tool (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O'Cathain, Rousseau, Vedel and Pluye2018; Pablo et al., Reference Pablo, Vaquerizo-Serrano, Catalan, Arango, Moreno, Ferre, Shin, Sullivan, Brondino, Solmi and Fusar-Poli2020; Usher et al., Reference Usher, Jackson, Durkin, Gyamfi and Bhullar2020). Two reviewers independently assessed and assigned scores to the studies using the tool dictionary and guidelines. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with the lead reviewer (RKD). The quality scores ranged from 0 to 7 (highest quality). Studies were categorised as high, medium, or low quality if they attained the score of 6, 5 to 6, or <5, respectively.

Effect measure and data analysis

Using Version 16.1 of Stata (metaprop package), a random-effects model was used to compute the pooled estimates of outcome prevalence between populations by assuming that these studies are randomly selected from their targeted populations in Latin America to generalise our results to comparable studies in the region (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2021). We computed prediction intervals to show the range of the effect sizes across studies (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Higgins, Hedges and Rothstein2017). The I 2 statistic was used to calculate variance difference from effect sizes in order to quantify heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Tianjing Li and Page2019). Visual inspection of the Doi plot and the Luis Furuya–Kanamori (Furuya-Kanamori et al., Reference Furuya-Kanamori, Barendregt and Doi2018) index were used to assess publication bias (Kounou et al., Reference Kounou, Guédénon, Foli and Gnassounou-Akpa2020; Yitayih et al., Reference Yitayih, Mekonen, Zeynudin, Mengistie and Ambelu2020). The event ratio was used as the primary effect measure for the pooled estimates.

Results

Screening of studies

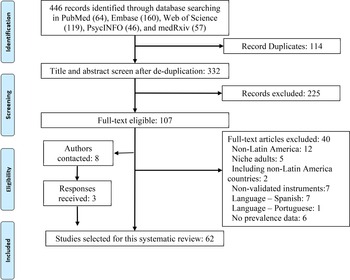

A total of 446 records were identified through searching bibliographical databases and other sources (Fig. 1). After removing 114 duplicates, a total of 332 records advanced to the screening phase. After excluding 225 records that did not pass the title and abstract screening, 107 records were identified as eligible for full-text screening. Among them, 40 papers were excluded for different reasons. For example, we excluded seven papers in Spanish and one paper in Portuguese. We sent emails to the authors of eight studies, to request missing critical information; three studies provided new prevalence data and were included in the final pool. Therefore, 62 studies, focused on populations in Latin America, were used in the final data extraction and analysis (online Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Study characteristics

A total of 65 unique samples from 62 studies involving 196 950 participants from Latin America were included in this meta-analysis (Badellino et al., Reference Badellino, Gobbo, Torres and Aschieri2020, Reference Badellino, Gobbo, Torres, Aschieri, Biotti, Alvarez, Gigante and Cachiarelli2022; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, Marôco, Saadiq and Ruano2020, Reference Campos, Campos, Bueno and Martins2021a, Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, de Fátima Valadão-Dias and Marôco2021b; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Farah, Dong, Chen, Xu, Yin, Chen, Delios, Miller, Wan and Zhang2021a, Reference Chen, Zhang, Xu, Yin, Dong, Chen, Delios, McIntyre, Miller and Wan2021b; Civantos et al., Reference Civantos, Bertelli, Gonçalves, Getzen, Chang, Long and Rajasekaran2020; Cortés-Álvarez et al., Reference Cortés-Álvarez, Pineiro-Lamas and Vuelvas-Olmos2020; Dal'Bosco et al., Reference Dal'Bosco, Floriano, Skupien, Arcaro, Martins and Anselmo2020; De Boni et al., Reference De Boni, Balanzá-Martínez, Mota, Cardoso, Ballester, Atienza-Carbonell, Bastos and Kapczinski2020; Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri and Pedreira2020; Giardino et al., Reference Giardino, Huck-Iriart, Riddick and Garay2020; Guiroy et al., Reference Guiroy, Gagliardi, Coombes, Landriel, Zanardi, Camino Willhuber, Guyot and Valacco2020; Malgor et al., Reference Malgor, Sobreira, Mouawad, Johnson, Wohlauer, Coogan, Cuff, Coleman, Sheahan and Woo2020; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Silva, Morigi, Zucoloto, Silva, Joaquim, Dall'Agnol, Galdino, Martinez and Silva2020; Medeiros et al., Reference Medeiros, Vieira, Silva, Rezende, Santos and Tabata2020; Mier-Bolio et al., Reference Mier-Bolio, Arroyo-González, Baques-Guillén, Valdez-Lopez, Torre-García, Rodríguez-Rodríguez and Rivera-Arroyo2020; Monterrosa-Castro et al., Reference Monterrosa-Castro, Redondo-Mendoza and Mercado-Lara2020; Mora-Magaña et al., Reference Mora-Magaña, Lee, Maldonado-Castellanos, Jiménez-Gutierrez, Mendez-Venegas, Maya-Del-Moral, Rosas-Munive, Mathis and Jobe2020; Passos et al., Reference Passos, Prazeres, Teixeira and Martins2020; Paz et al., Reference Paz, Mascialino, Adana-Díaz, Rodríguez-Lorenzana, Simbaña-Rivera, Gómez-Barreno, Troya, Páez, Cardenas and Gerstner2020; Samaniego et al., Reference Samaniego, Urzúa, Buenahora and Vera-Villarroel2020; Schuch et al., Reference Schuch, Bulzing, Meyer, Vancampfort, Firth, Stubbs, Grabovac, Willeit, Tavares and Calegaro2020; Yáñez et al., Reference Yáñez, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Li and Zhang2020; Antiporta et al., Reference Antiporta, Cutipe, Mendoza, Celentano, Stuart and Bruni2021; Boluarte-Carbajal et al., Reference Boluarte-Carbajal, Navarro-Flores and Villarreal-Zegarra2021; Brito-Marques et al., Reference Brito-Marques, Franco, de Brito-Marques, Martinez and do Prado2021; Cayo-Rojas et al., Reference Cayo-Rojas, Castro-Mena, Agramonte-Rosell, Aliaga-Mariñas, Ladera-Castañeda, Cervantes-Ganoza and Cervantes-Liñán2021; Cénat et al., Reference Cénat, Dalexis, Guerrier, Noorishad, Derivois, Bukaka, Birangui, Adansikou, Clorméus and Kokou-Kpolou2021; Dantas et al., Reference Dantas, Araújo Filho, Silva, Silveira, Dantas and Meira2021; de Oliveira Andrade et al., Reference de Oliveira Andrade, Correia Silva Azambuja, Carvalho Reis Martins, Manoel Seixas and Moretti Luchesi2021; Espinosa-Guerra et al., Reference Espinosa-Guerra, Rodríguez-Barría, Donnelly and Carrera2021; Esteves et al., Reference Esteves, de Oliveira and Argimon2021; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Vieira, Silva, Cardoso, Bielavski, Rakovski and Silva2021; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Lopes-Silva, Siquara, Manfroi and de Freitas2021; Feter et al., Reference Feter, Caputo, Doring, Leite, Cassuriaga, Reichert, da Silva, Coombes and Rombaldi2021; Flores-Torres et al., Reference Flores-Torres, Murchland, Espinosa-Tamez, Jaen, Brochier, Bautista-Arredondo, Lamadrid-Figueroa, Lajous and Koenen2021; García-Espinosa et al., Reference García-Espinosa, Ortiz-Jiménez, Botello-Hernández, Aguayo-Samaniego, Leija-Herrera and Góngora-Rivera2021; Goularte et al., Reference Goularte, Serafim, Colombo, Hogg, Caldieraro and Rosa2021; Landaeta-Díaz et al., Reference Landaeta-Díaz, González-Medina and Agüero2021; Loret de Mola et al., Reference Loret de Mola, Blumenberg, Martins, Martins-Silva, Carpena, Del-Ponte, Pearson, Soares and Cesar2021; Mautong et al., Reference Mautong, Gallardo-Rumbea, Alvarado-Villa, Fernández-Cadena, Andrade-Molina, Orellana-Román and Cherrez-Ojeda2021; Mendonca et al., Reference Mendonca, Steil and Gois2021; Mota et al., Reference Mota, Oliveira Sobrinho, Morais and Dantas2021; Nayak et al., Reference Nayak, Sahu, Ramsaroop, Maharaj, Mootoo, Khan and Extravour2021; Puccinelli et al., Reference Puccinelli, Costa, Seffrin, de Lira, Vancini, Knechtle, Nikolaidis and Andrade2021; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lessa, Delmolin and Santos2021; Schmitt Jr et al., Reference Schmitt, Brenner, Primo de Carvalho Alves, Claudino, Fleck and Rocha2021; Scotta et al., Reference Scotta, Cortez and Miranda2021; Serafim et al., Reference Serafim, Durães, Rocca, Gonçalves, Saffi, Cappellozza, Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos and Brites2021; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Souza, Souza, Cordeiro, Praciano, Alves, Santos, Silva Junior and Souza2021; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Manes and Cetkovich2021a, Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Vázquez, Manes and Cetkovich2021b; Villela et al., Reference Villela, da Cunha, Fodjo, Obimpeh, Colebunders and Van Hees2021; Vitorino et al., Reference Vitorino, Yoshinari, Gonzaga, Dias, Pereira, Ribeiro, Franca, Al-Zaben, Koenig and Trzesniak2021; Werneck et al., Reference Werneck, Silva, Malta, Souza-Júnior, Azevedo, Barros and Szwarcwald2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Patty-Tito2021a, Reference Zhang, Wang, Jahanshahi, Li and Schmitt2021c; da Silva Júnior et al., Reference da Silva Júnior, de Lima Macena, de Oliveira, Praxedes, de Oliveira Maranhão Pureza and Bueno2021; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodríguez, Vega-Ramírez, Álvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chainé, Astudillo, Real-Ramírez and Medina-Mora2021) (Table 1 and online Supplementary Table S2). Some studies include multiple independent samples. For example, one study examined the prevalence of both general healthcare workers and frontline healthcare workers. Among them, 35 samples (53.85%) were of general populations (Passos et al., Reference Passos, Prazeres, Teixeira and Martins2020; Antiporta et al., Reference Antiporta, Cutipe, Mendoza, Celentano, Stuart and Bruni2021; Boluarte-Carbajal et al., Reference Boluarte-Carbajal, Navarro-Flores and Villarreal-Zegarra2021; de Oliveira Andrade et al., Reference de Oliveira Andrade, Correia Silva Azambuja, Carvalho Reis Martins, Manoel Seixas and Moretti Luchesi2021; Espinosa-Guerra et al., Reference Espinosa-Guerra, Rodríguez-Barría, Donnelly and Carrera2021; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Lopes-Silva, Siquara, Manfroi and de Freitas2021; Landaeta-Díaz et al., Reference Landaeta-Díaz, González-Medina and Agüero2021; Mautong et al., Reference Mautong, Gallardo-Rumbea, Alvarado-Villa, Fernández-Cadena, Andrade-Molina, Orellana-Román and Cherrez-Ojeda2021; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lessa, Delmolin and Santos2021; Schmitt Jr et al., Reference Schmitt, Brenner, Primo de Carvalho Alves, Claudino, Fleck and Rocha2021; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Souza, Souza, Cordeiro, Praciano, Alves, Santos, Silva Junior and Souza2021; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Vázquez, Manes and Cetkovich2021b; Vitorino et al., Reference Vitorino, Yoshinari, Gonzaga, Dias, Pereira, Ribeiro, Franca, Al-Zaben, Koenig and Trzesniak2021; Badellino et al., Reference Badellino, Gobbo, Torres, Aschieri, Biotti, Alvarez, Gigante and Cachiarelli2022), two samples (3.08%) were of frontline healthcare workers (Dal'Bosco et al., Reference Dal'Bosco, Floriano, Skupien, Arcaro, Martins and Anselmo2020; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodríguez, Vega-Ramírez, Álvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chainé, Astudillo, Real-Ramírez and Medina-Mora2021), 19 samples (29.22%) were from general healthcare workers (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Ibarra2020; Civantos et al., Reference Civantos, Bertelli, Gonçalves, Getzen, Chang, Long and Rajasekaran2020; Giardino et al., Reference Giardino, Huck-Iriart, Riddick and Garay2020; Guiroy et al., Reference Guiroy, Gagliardi, Coombes, Landriel, Zanardi, Camino Willhuber, Guyot and Valacco2020; Malgor et al., Reference Malgor, Sobreira, Mouawad, Johnson, Wohlauer, Coogan, Cuff, Coleman, Sheahan and Woo2020; Monterrosa-Castro et al., Reference Monterrosa-Castro, Redondo-Mendoza and Mercado-Lara2020; Mora-Magaña et al., Reference Mora-Magaña, Lee, Maldonado-Castellanos, Jiménez-Gutierrez, Mendez-Venegas, Maya-Del-Moral, Rosas-Munive, Mathis and Jobe2020; Samaniego et al., Reference Samaniego, Urzúa, Buenahora and Vera-Villarroel2020; Yáñez et al., Reference Yáñez, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Li and Zhang2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Patty-Tito2021a; Villela et al., Reference Villela, da Cunha, Fodjo, Obimpeh, Colebunders and Van Hees2021; Nayak et al., Reference Nayak, Sahu, Ramsaroop, Maharaj, Mootoo, Khan and Extravour2021; Dantas et al., Reference Dantas, Araújo Filho, Silva, Silveira, Dantas and Meira2021; Mota et al., Reference Mota, Oliveira Sobrinho, Morais and Dantas2021; Brito-Marques et al., Reference Brito-Marques, Franco, de Brito-Marques, Martinez and do Prado2021; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, de Fátima Valadão-Dias and Marôco2021b; Mier-Bolio et al., Reference Mier-Bolio, Arroyo-González, Baques-Guillén, Valdez-Lopez, Torre-García, Rodríguez-Rodríguez and Rivera-Arroyo2020; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodríguez, Vega-Ramírez, Álvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chainé, Astudillo, Real-Ramírez and Medina-Mora2021) and nine samples (13.85%) were based on university students (Medeiros et al., Reference Medeiros, Vieira, Silva, Rezende, Santos and Tabata2020; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Campos, Bueno and Martins2021a; Cayo-Rojas et al., Reference Cayo-Rojas, Castro-Mena, Agramonte-Rosell, Aliaga-Mariñas, Ladera-Castañeda, Cervantes-Ganoza and Cervantes-Liñán2021; Esteves et al., Reference Esteves, de Oliveira and Argimon2021; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Vieira, Silva, Cardoso, Bielavski, Rakovski and Silva2021; García-Espinosa et al., Reference García-Espinosa, Ortiz-Jiménez, Botello-Hernández, Aguayo-Samaniego, Leija-Herrera and Góngora-Rivera2021; Mendonca et al., Reference Mendonca, Steil and Gois2021; Scotta et al., Reference Scotta, Cortez and Miranda2021; da Silva Júnior et al., Reference da Silva Júnior, de Lima Macena, de Oliveira, Praxedes, de Oliveira Maranhão Pureza and Bueno2021). Of the 62 studies, 32 were from Brazil (49.22%) (Table 1). Except for three (4.84%) longitudinal cohort studies (Feter et al., Reference Feter, Caputo, Doring, Leite, Cassuriaga, Reichert, da Silva, Coombes and Rombaldi2021; Flores-Torres et al., Reference Flores-Torres, Murchland, Espinosa-Tamez, Jaen, Brochier, Bautista-Arredondo, Lamadrid-Figueroa, Lajous and Koenen2021; Loret de Mola et al., Reference Loret de Mola, Blumenberg, Martins, Martins-Silva, Carpena, Del-Ponte, Pearson, Soares and Cesar2021), the majority of the studies were cross-sectional (95.16%). The sample size varied from 62 to 196 950 participants. The participation rates varied from 11.4% to 100.0% with a median value of 72.25%. The female proportions among the 65 samples varied from 3.4% to 89.8% with a median of 72.25%.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies on mental health in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic

a Some studies include multiple independent samples. For example, one study47examined the prevalence of both general healthcare workers and frontline healthcare workers.

b One independent sample in a study may report anxiety, depression and insomnia at the levels of mild above, moderate above and severe. Therefore, the total number of prevalence is larger than the total number of independent samples.

Estimates of pooled prevalence of psychological morbidity symptoms

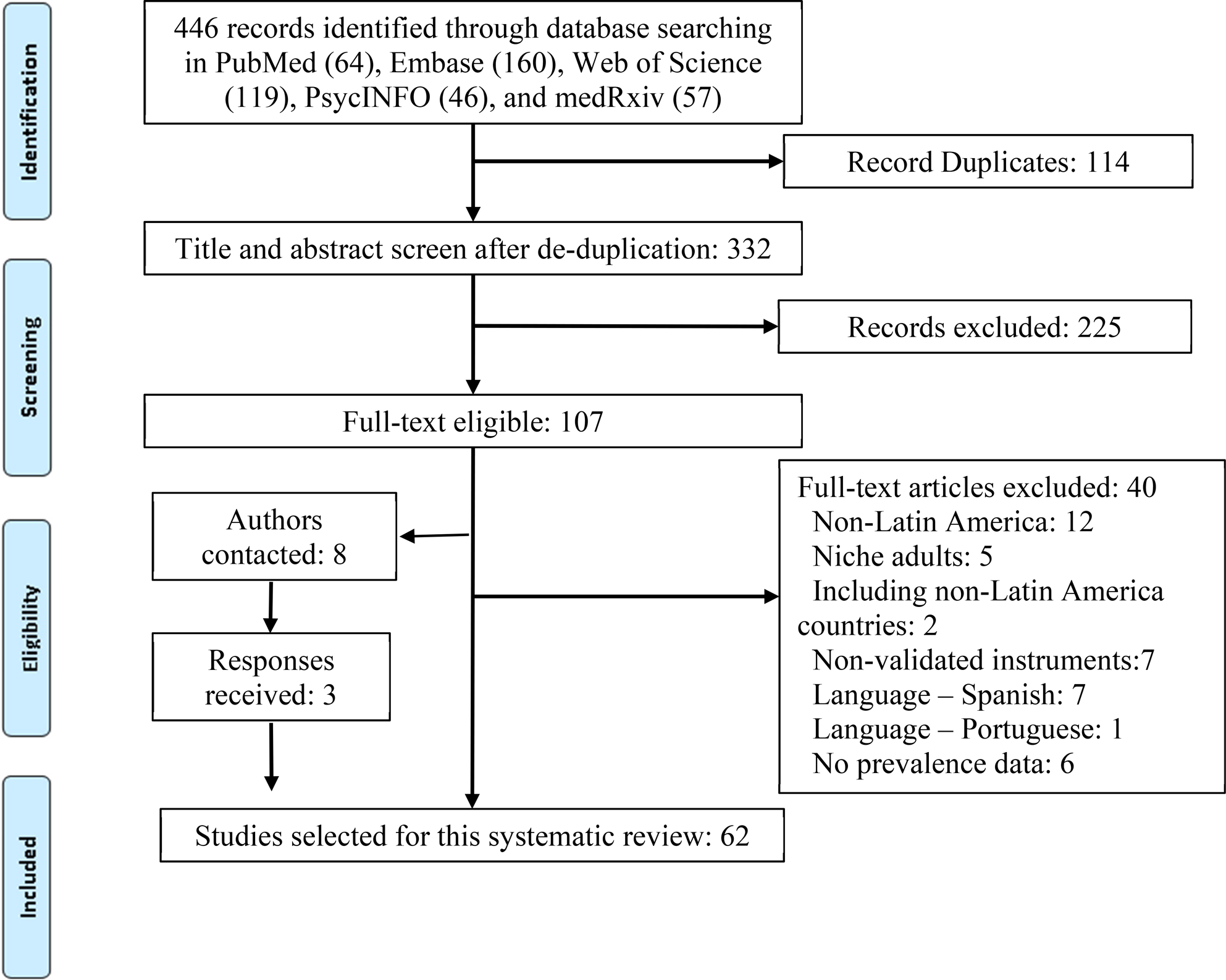

In Latin America, 56 samples from 54 studies reported the prevalence of anxiety symptoms among 128 060 participants (Badellino et al., Reference Badellino, Gobbo, Torres and Aschieri2020; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, Marôco, Saadiq and Ruano2020, Reference Campos, Campos, Bueno and Martins2021a, Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, de Fátima Valadão-Dias and Marôco2021b; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Ibarra2020; Civantos et al., Reference Civantos, Bertelli, Gonçalves, Getzen, Chang, Long and Rajasekaran2020; Cortés-Álvarez et al., Reference Cortés-Álvarez, Pineiro-Lamas and Vuelvas-Olmos2020; Dal'Bosco et al., Reference Dal'Bosco, Floriano, Skupien, Arcaro, Martins and Anselmo2020; De Boni et al., Reference De Boni, Balanzá-Martínez, Mota, Cardoso, Ballester, Atienza-Carbonell, Bastos and Kapczinski2020; Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri and Pedreira2020; Malgor et al., Reference Malgor, Sobreira, Mouawad, Johnson, Wohlauer, Coogan, Cuff, Coleman, Sheahan and Woo2020; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Silva, Morigi, Zucoloto, Silva, Joaquim, Dall'Agnol, Galdino, Martinez and Silva2020; Medeiros et al., Reference Medeiros, Vieira, Silva, Rezende, Santos and Tabata2020; Mier-Bolio et al., Reference Mier-Bolio, Arroyo-González, Baques-Guillén, Valdez-Lopez, Torre-García, Rodríguez-Rodríguez and Rivera-Arroyo2020; Monterrosa-Castro et al., Reference Monterrosa-Castro, Redondo-Mendoza and Mercado-Lara2020; Mora-Magaña et al., Reference Mora-Magaña, Lee, Maldonado-Castellanos, Jiménez-Gutierrez, Mendez-Venegas, Maya-Del-Moral, Rosas-Munive, Mathis and Jobe2020; Passos et al., Reference Passos, Prazeres, Teixeira and Martins2020; Paz et al., Reference Paz, Mascialino, Adana-Díaz, Rodríguez-Lorenzana, Simbaña-Rivera, Gómez-Barreno, Troya, Páez, Cardenas and Gerstner2020; Samaniego et al., Reference Samaniego, Urzúa, Buenahora and Vera-Villarroel2020; Schuch et al., Reference Schuch, Bulzing, Meyer, Vancampfort, Firth, Stubbs, Grabovac, Willeit, Tavares and Calegaro2020; Yáñez et al., Reference Yáñez, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Li and Zhang2020; Boluarte-Carbajal et al., Reference Boluarte-Carbajal, Navarro-Flores and Villarreal-Zegarra2021; Cayo-Rojas et al., Reference Cayo-Rojas, Castro-Mena, Agramonte-Rosell, Aliaga-Mariñas, Ladera-Castañeda, Cervantes-Ganoza and Cervantes-Liñán2021; Cénat et al., Reference Cénat, Dalexis, Guerrier, Noorishad, Derivois, Bukaka, Birangui, Adansikou, Clorméus and Kokou-Kpolou2021; Dantas et al., Reference Dantas, Araújo Filho, Silva, Silveira, Dantas and Meira2021; de Oliveira Andrade et al., Reference de Oliveira Andrade, Correia Silva Azambuja, Carvalho Reis Martins, Manoel Seixas and Moretti Luchesi2021; Espinosa-Guerra et al., Reference Espinosa-Guerra, Rodríguez-Barría, Donnelly and Carrera2021; Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Vieira, Silva, Cardoso, Bielavski, Rakovski and Silva2021; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Lopes-Silva, Siquara, Manfroi and de Freitas2021; Feter et al., Reference Feter, Caputo, Doring, Leite, Cassuriaga, Reichert, da Silva, Coombes and Rombaldi2021; Flores-Torres et al., Reference Flores-Torres, Murchland, Espinosa-Tamez, Jaen, Brochier, Bautista-Arredondo, Lamadrid-Figueroa, Lajous and Koenen2021; García-Espinosa et al., Reference García-Espinosa, Ortiz-Jiménez, Botello-Hernández, Aguayo-Samaniego, Leija-Herrera and Góngora-Rivera2021; Giardino et al., Reference Giardino, Huck-Iriart, Riddick and Garay2020; Goularte et al., Reference Goularte, Serafim, Colombo, Hogg, Caldieraro and Rosa2021; Landaeta-Díaz et al., Reference Landaeta-Díaz, González-Medina and Agüero2021; Loret de Mola et al., Reference Loret de Mola, Blumenberg, Martins, Martins-Silva, Carpena, Del-Ponte, Pearson, Soares and Cesar2021; Mautong et al., Reference Mautong, Gallardo-Rumbea, Alvarado-Villa, Fernández-Cadena, Andrade-Molina, Orellana-Román and Cherrez-Ojeda2021; Mendonca et al., Reference Mendonca, Steil and Gois2021; Nayak et al., Reference Nayak, Sahu, Ramsaroop, Maharaj, Mootoo, Khan and Extravour2021; Puccinelli et al., Reference Puccinelli, Costa, Seffrin, de Lira, Vancini, Knechtle, Nikolaidis and Andrade2021; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lessa, Delmolin and Santos2021; Serafim et al., Reference Serafim, Durães, Rocca, Gonçalves, Saffi, Cappellozza, Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos and Brites2021; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Souza, Souza, Cordeiro, Praciano, Alves, Santos, Silva Junior and Souza2021; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Manes and Cetkovich2021a, Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Vázquez, Manes and Cetkovich2021b; Vitorino et al., Reference Vitorino, Yoshinari, Gonzaga, Dias, Pereira, Ribeiro, Franca, Al-Zaben, Koenig and Trzesniak2021; Werneck et al., Reference Werneck, Silva, Malta, Souza-Júnior, Azevedo, Barros and Szwarcwald2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Patty-Tito2021a, Reference Zhang, Huang, Li, Antonelli-Ponti, Paiva and Silva2021b; Caycho-Rodriguez et al., Reference Caycho-Rodriguez, Tomas, Vilca, Garcia, Rojas-Jara, White and Pena-Calero2022;; da Silva Júnior et al., Reference da Silva Júnior, de Lima Macena, de Oliveira, Praxedes, de Oliveira Maranhão Pureza and Bueno2021; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodríguez, Vega-Ramírez, Álvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chainé, Astudillo, Real-Ramírez and Medina-Mora2021). Among all the anxiety survey tools used, the Generalised Anxiety Symptoms 7-items scale (GAD-7) was the most common (51.85%), followed by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items (DASS-21) (18.52%), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (9.26%), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (3.70%) and nine others (each 1.85%). The cut-off values to determine the overall prevalence as well as severe anxiety varied across studies. In the random-effects model, the pooled prevalence of anxiety was 35% (95% CI: 31–38%) in the 54 studies (Fig. 2a). This finding suggests that, on average, 35% of the adults in Latin America had anxiety symptoms during COVID-19. Based on a normal distribution, its prediction internal is 5−75%, and the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in any comparable study will fall in this range.

Fig. 2. The square markers indicate the prevalence of insomnia symptoms among population groups of interest. The diamonds represent the pooled estimates. (a) Forest plot indicating the pooled prevalence of anxiety among included studies. (b) Forest plot indicating the pooled prevalence of depression among included studies. (c) Forest plot indicating the pooled prevalence of distress among included studies. (d) Forest plot indicating the pooled prevalence of insomnia among included studies.

A total of 49 samples from 46 studies reported the prevalence of depression among 139 559 respondents (Badellino et al., Reference Badellino, Gobbo, Torres and Aschieri2020, Reference Badellino, Gobbo, Torres, Aschieri, Biotti, Alvarez, Gigante and Cachiarelli2022; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Martins, Campos, Marôco, Saadiq and Ruano2020; Civantos et al., Reference Civantos, Bertelli, Gonçalves, Getzen, Chang, Long and Rajasekaran2020; Cortés-Álvarez et al., Reference Cortés-Álvarez, Pineiro-Lamas and Vuelvas-Olmos2020; Dal'Bosco et al., Reference Dal'Bosco, Floriano, Skupien, Arcaro, Martins and Anselmo2020; De Boni et al., Reference De Boni, Balanzá-Martínez, Mota, Cardoso, Ballester, Atienza-Carbonell, Bastos and Kapczinski2020; Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri and Pedreira2020; Giardino et al., Reference Giardino, Huck-Iriart, Riddick and Garay2020; Guiroy et al., Reference Guiroy, Gagliardi, Coombes, Landriel, Zanardi, Camino Willhuber, Guyot and Valacco2020; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Silva, Morigi, Zucoloto, Silva, Joaquim, Dall'Agnol, Galdino, Martinez and Silva2020; Medeiros et al., Reference Medeiros, Vieira, Silva, Rezende, Santos and Tabata2020; Mora-Magaña et al., Reference Mora-Magaña, Lee, Maldonado-Castellanos, Jiménez-Gutierrez, Mendez-Venegas, Maya-Del-Moral, Rosas-Munive, Mathis and Jobe2020; Passos et al., Reference Passos, Prazeres, Teixeira and Martins2020; Paz et al., Reference Paz, Mascialino, Adana-Díaz, Rodríguez-Lorenzana, Simbaña-Rivera, Gómez-Barreno, Troya, Páez, Cardenas and Gerstner2020; Samaniego et al., Reference Samaniego, Urzúa, Buenahora and Vera-Villarroel2020; Schuch et al., Reference Schuch, Bulzing, Meyer, Vancampfort, Firth, Stubbs, Grabovac, Willeit, Tavares and Calegaro2020; Antiporta et al., Reference Antiporta, Cutipe, Mendoza, Celentano, Stuart and Bruni2021; Boluarte-Carbajal et al., Reference Boluarte-Carbajal, Navarro-Flores and Villarreal-Zegarra2021; de Oliveira Andrade et al., Reference de Oliveira Andrade, Correia Silva Azambuja, Carvalho Reis Martins, Manoel Seixas and Moretti Luchesi2021; Espinosa-Guerra et al., Reference Espinosa-Guerra, Rodríguez-Barría, Donnelly and Carrera2021; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Lopes-Silva, Siquara, Manfroi and de Freitas2021; Feter et al., Reference Feter, Caputo, Doring, Leite, Cassuriaga, Reichert, da Silva, Coombes and Rombaldi2021; García-Espinosa et al., Reference García-Espinosa, Ortiz-Jiménez, Botello-Hernández, Aguayo-Samaniego, Leija-Herrera and Góngora-Rivera2021; Goularte et al., Reference Goularte, Serafim, Colombo, Hogg, Caldieraro and Rosa2021; Loret de Mola et al., Reference Loret de Mola, Blumenberg, Martins, Martins-Silva, Carpena, Del-Ponte, Pearson, Soares and Cesar2021; Mautong et al., Reference Mautong, Gallardo-Rumbea, Alvarado-Villa, Fernández-Cadena, Andrade-Molina, Orellana-Román and Cherrez-Ojeda2021; Mendonca et al., Reference Mendonca, Steil and Gois2021; Nayak et al., Reference Nayak, Sahu, Ramsaroop, Maharaj, Mootoo, Khan and Extravour2021; Puccinelli et al., Reference Puccinelli, Costa, Seffrin, de Lira, Vancini, Knechtle, Nikolaidis and Andrade2021; Ribeiro et al., Reference Ribeiro, Lessa, Delmolin and Santos2021; Schmitt Jr et al., Reference Schmitt, Brenner, Primo de Carvalho Alves, Claudino, Fleck and Rocha2021; Serafim et al., Reference Serafim, Durães, Rocca, Gonçalves, Saffi, Cappellozza, Paulino, Dumas-Diniz, Brissos and Brites2021; Souza et al., Reference Souza, Souza, Souza, Cordeiro, Praciano, Alves, Santos, Silva Junior and Souza2021; Torrente et al., Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Manes and Cetkovich2021a, Reference Torrente, Yoris, Low, Lopez, Bekinschtein, Vázquez, Manes and Cetkovich2021b; Villela et al., Reference Villela, da Cunha, Fodjo, Obimpeh, Colebunders and Van Hees2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Patty-Tito2021a, Reference Zhang, Huang, Li, Antonelli-Ponti, Paiva and Silva2021b; Caycho-Rodriguez et al., Reference Caycho-Rodriguez, Tomas, Vilca, Garcia, Rojas-Jara, White and Pena-Calero2022; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodríguez, Vega-Ramírez, Álvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chainé, Astudillo, Real-Ramírez and Medina-Mora2021). Among all the depression survey tools, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 was the most frequently used (50%), followed by DASS-21 (21.74), HADS (10.87%), the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) (4.35%) and six others (each 2.17%). Analysing the random-effects model, the pooled prevalence of depression was 35% (95% CI: 31−39%) among the 46 studies (Fig. 2b). This finding suggests that, on average, 35% of the adults in Latin America had depression symptoms during COVID-19. Its prediction internal is 7−71%.

Thirteen studies studied mental distress among 10 335 participants (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Dai, Li and Ibarra2020; Civantos et al., Reference Civantos, Bertelli, Gonçalves, Getzen, Chang, Long and Rajasekaran2020; Cortés-Álvarez et al., Reference Cortés-Álvarez, Pineiro-Lamas and Vuelvas-Olmos2020; Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Crivelli, Guimet, Allegri and Pedreira2020; Reidy, Reference Reidy2020; Samaniego et al., Reference Samaniego, Urzúa, Buenahora and Vera-Villarroel2020; Yáñez et al., Reference Yáñez, Jahanshahi, Alvarez-Risco, Li and Zhang2020; Boluarte-Carbajal et al., Reference Boluarte-Carbajal, Navarro-Flores and Villarreal-Zegarra2021; Espinosa-Guerra et al., Reference Espinosa-Guerra, Rodríguez-Barría, Donnelly and Carrera2021; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Lopes-Silva, Siquara, Manfroi and de Freitas2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Jahanshahi, Li and Schmitt2021c). Among all the distress survey tools, DASS-21 was the most frequently used (30.77%), followed by COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index (CPDI), Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES) and K6 (15.38% each) and three others (7.69% each). In the random-effects model, the pooled prevalence of distress was 32% (95% CI: 25–40%) (Fig. 2c). This finding suggests that, on average, 32% of the adults in Latin America had distress symptoms during COVID-19. Its prediction interval is 1–79%.

Nine samples from seven studies (Giardino et al., Reference Giardino, Huck-Iriart, Riddick and Garay2020; Samaniego et al., Reference Samaniego, Urzúa, Buenahora and Vera-Villarroel2020; Brito-Marques et al., Reference Brito-Marques, Franco, de Brito-Marques, Martinez and do Prado2021; Goularte et al., Reference Goularte, Serafim, Colombo, Hogg, Caldieraro and Rosa2021; Mota et al., Reference Mota, Oliveira Sobrinho, Morais and Dantas2021; Scotta et al., Reference Scotta, Cortez and Miranda2021; Robles et al., Reference Robles, Rodríguez, Vega-Ramírez, Álvarez-Icaza, Madrigal, Durand, Morales-Chainé, Astudillo, Real-Ramírez and Medina-Mora2021) studied insomnia among 12 134 respondents. The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (71.43%) was used most often, followed by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (28.57). In the random-effects model, the pooled prevalence of insomnia was 35% (95% CI: 25–46%) (Fig. 2d). Its prediction interval is 1–86%. The finding suggests that, on average, 35% of the adults in Latin America had insomnia symptoms during COVID-19 and the prevalence of insomnia symptoms in any comparable study will fall in this range.

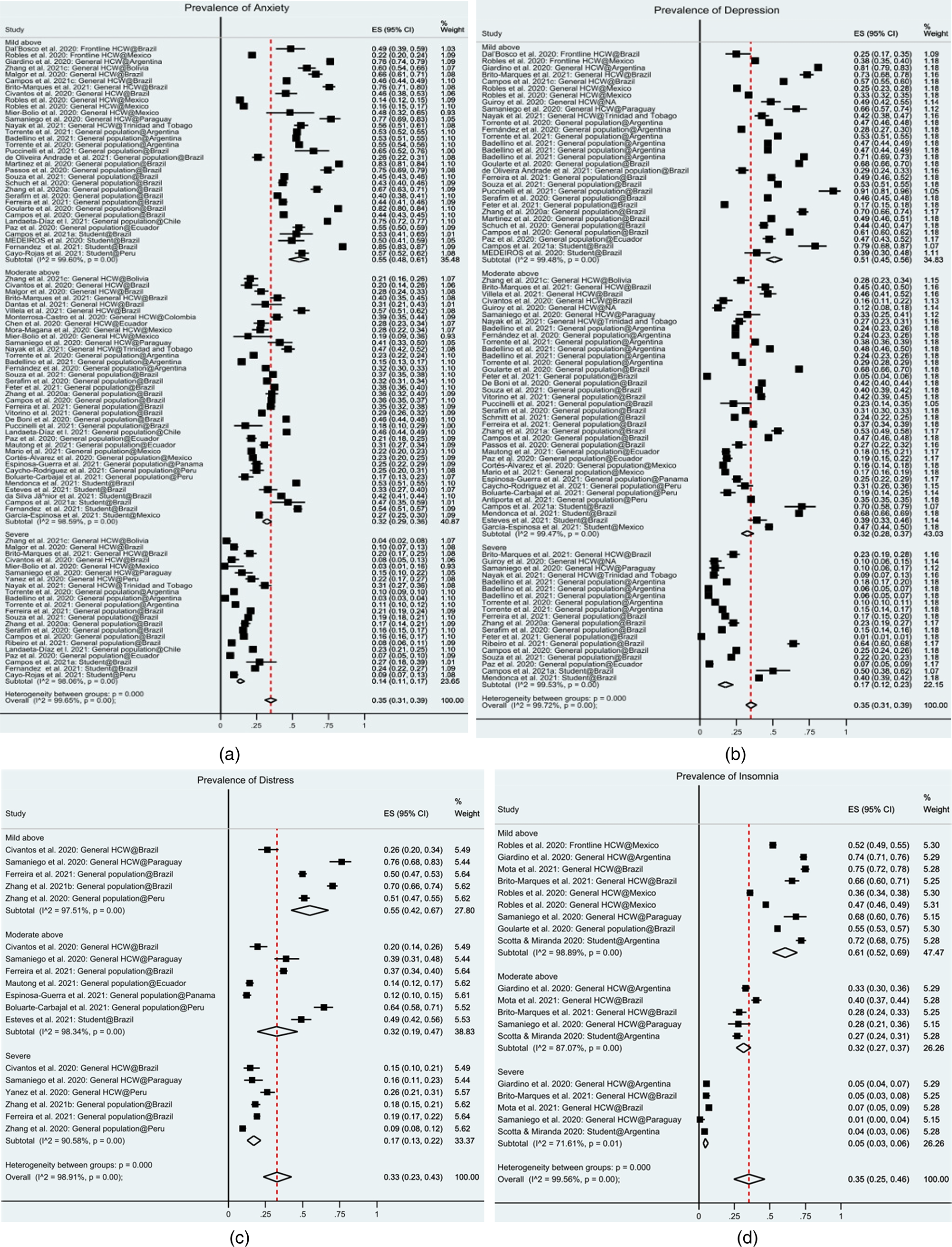

The overall prevalence of mental health symptoms in frontline healthcare workers, general healthcare workers, the general population and students in Latin America was 37%, 34%, 33% and 45%, respectively. The overall prevalence rates of mental health symptoms that exceeded the cut-off values of mild, moderate and severe symptoms were 54%, 32% and 14%, respectively (Table 2). The pooled prevalence rates of mental health symptoms in South America, Central America, countries speaking Spanish and countries speaking Portuguese were 36%, 28%, 30% and 40%, respectively (Table 2). Subgroup analyses results on the anxiety, depression, distress and insomnia by population, severity, region and instrument are reported in Table 3.

Table 2. Pooled prevalence estimates of mental health symptoms by outcome, population, severity and region subgroups during the COVID-19 pandemic

CI, confidence interval.

Table 3. Subgroup analyses of the prevalence of anxiety, depression and insomnia symptoms

CI, confidence interval.

Quality of the studies

Of all studies, 30 studies (48.39%) were of high quality, and 32 studies (51.61%) were of medium quality (Table 1). The subgroup analysis suggests the high-quality studies reported a higher prevalence of mental health symptoms in Latin America (42%) than those of medium quality (31%) (Table 2).

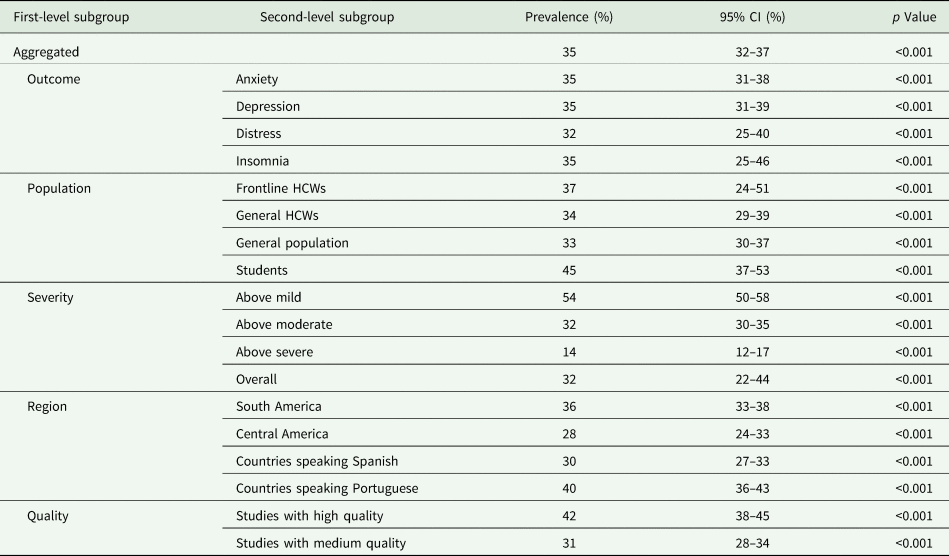

Detection of publication bias

The Doi plot and Luis Furuya–Kanamori index were used to quantify publication bias rather than the funnel plot and Egger's statistics (Furuya-Kanamori et al., Reference Furuya-Kanamori, Barendregt and Doi2018; Kounou et al., Reference Kounou, Guédénon, Foli and Gnassounou-Akpa2020). The symmetrical, hill-shaped Doi plot and a Luis Furuya–Kanamori (LFK) index of −0.81 indicated ‘no asymmetry’ and a lower likelihood of publication bias (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The Doi plot and the Luis Furuya–Kanamori (LFK) index for publication bias. ES, effect size.

Discussion

The analysis of 62 studies with 196 950 participants from Latin America generated pooled prevalence of anxiety, depression, distress and insomnia of 35%, 35%, 32% and 35%, respectively. Notably, this meta-analysis is the first to investigate the prevalence of mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 crisis in Latin America. The anxiety levels in Latin America were significantly higher than other regions, such as China (25%; p < 0.001 (We compared the prevalence between two regions using t-test https://www.medcalc.org/calc/comparison_of_proportions.php)) (Ren et al., Reference Ren, Huang, Pan, Huang, Wang and Ma2020) and Spain (20%; p < 0.001) (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Xu, Yin, Dong, Chen, Delios, McIntyre, Miller and Wan2021b). Latin America has a long-standing history of scarce resources to deal with mental health symptoms (Alarcón, Reference Alarcón2003), which could explain the higher prevalence of mental health symptoms among Latin Americans as revealed by this meta-analysis. Notably, the pooled prevalence of mental health symptoms was lower in Latin America than in Africa and South Asia, as reported by other meta-analyses (Hossain et al., Reference Hossain, Purohit, Sultan, Ma, Lisako, McKyer and Ahmed2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Farah, Dong, Chen, Xu, Yin, Chen, Delios, Miller, Wan and Zhang2021a). These cross-region differences may be due to multiple reasons, including heterogeneity in COVID-19 infection rate and mortality rate, variations in and timing of containment strategies adopted by countries across regions (Middelburg and Rosendaal, Reference Middelburg and Rosendaal2020), and the varying degrees of resources available, including personal protective equipment (PPE), to address mental health symptoms (Batra et al., Reference Batra, Singh, Sharma, Batra and Schvaneveldt2020).

The prevalence of mental health symptoms was higher in South America than Central America (36% v. 28%; p < 0.001). This difference might be attributed to variations across these countries in the evolution of the pandemic (e.g. some countries such as Peru and Brazil started out well but deteriorated rapidly) (We appreciate a reviewer raising this point of discussion.), the provision and availability of PPE, healthcare facilities and capacities, the stringency of the COVID-19 responses and the political climate (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Alarcón, Bayer, Buss, Guerra, Ribeiro, Rojas, Saenz, Snyder, Solimano, Torres, Tobar, Tuesca, Vargas and Atun2020). Previous research noted that South America generally has a high degree of political polarisation, which resulted in conflicting information being conveyed to the public that could increase the burden of COVID-19 and its associated psychological corollaries (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Alarcón, Bayer, Buss, Guerra, Ribeiro, Rojas, Saenz, Snyder, Solimano, Torres, Tobar, Tuesca, Vargas and Atun2020). In addition, public health actions or decisions were made mostly at municipal and state levels rather than at central government levels, and the lack of central coordination posed several challenges in the control of the pandemic, contributing to an increased psychological burden (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Alarcón, Bayer, Buss, Guerra, Ribeiro, Rojas, Saenz, Snyder, Solimano, Torres, Tobar, Tuesca, Vargas and Atun2020).

Based on the evidence of individual studies, our study found a higher prevalence of mental health symptoms among frontline HCWs (37%, p < 0.001) and university students (45%, p < 0.001) than the general population and general HCWs (Batra et al., Reference Batra, Singh, Sharma, Batra and Schvaneveldt2020; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Guo, Yu, Jiang and Wang2020; Pappa et al., Reference Pappa, Ntella, Giannakas, Giannakoulis, Papoutsi and Katsaounou2020). The vulnerabilities of frontline healthcare workers are often attributed to a higher risk of infection, burnout, the more direct exposure to suffering or dying patients, fear of COVID-19 transmission to their family members and job loss (Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Yang, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Cheung and Ng2020; Bhandari et al., Reference Bhandari, Batra, Upadhyay and Cochran2021). The greater prevalence of mental health symptoms among university students can be explained by the uncertainties surrounding the course of the pandemic and the sudden transition to online education (Adedoyin and Soykan, Reference Adedoyin and Soykan2020; Batra et al., Reference Batra, Sharma, Batra, Singh and Schvaneveldt2021). Moreover, many businesses scaled down their recruitment efforts, leading to limited employment opportunities for students and more competition in the graduate labour market (Reidy, Reference Reidy2020). These challenges added to the mental health burden among university students.

Study limitations

There are a few limitations that merit discussion. First our analysis reveals substantial heterogeneities across studies in the type of survey instruments used and the cut-off scores, both of which may affect the interpretation of the findings. Second, not all Latin American countries have been well-studied, therefore our results may have limited generalisability for the less studied nations. Third, a majority of the included studies were cross-sectional, which provides no information on the prevalence over time during the pandemic. In addition, studies included in this meta-analysis relied on self-reported data of psychological symptoms by the participants and hence do not constitute mental health diagnosis from clinicians. Fourth, other outcomes, such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicidal ideation and burnout, were not studied in this meta-analysis, leaving opportunities for prospective studies. Last, a language bias is expected because of the language restriction (only English) applied in this study. The systematic search uncovered eight papers (7.5%) that were not included for language reasons out of 107 eligible papers.

Practical implications

First, our systematic review and meta-analysis support evidence-based medicine by revealing a high proportion of mental health symptoms among the general population and healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America. However, our systematic review also reveals there is a lack of evidence in many Latin American countries to guide the relevant practice of evidence-based medicine on this topic. Only 12 of the 33 Latin American countries have been studied, leaving 21 countries without any studies to assist the practice of evidence-based healthcare. For instance, no relevant research has been done in Venezuela, the fifth-biggest South American country with a population of 28 million, in Chile, the sixth biggest South American country with a population of 18 million, nor in Guatemala (18 million population), Cuba (11 million population) and the Dominican Republic (11 million population), respectively the second, fourth and fifth most populous countries in Central America. In practice, healthcare organisations in those unstudied countries may use our results in the same region as approximate evidence before direct evidence in those countries emerges.

Our findings that the prevalence of mental health symptoms was higher in South America than Central America (36% v. 28%; p < 0.001) provide evidence for international healthcare organisations, such as the World Psychiatric Association, on their assistance and resource allocation efforts. Our findings of a higher prevalence of mental health symptoms among frontline healthcare workers (37%, p < 0.001) and university students (45%, p < 0.001) than the general population (33%) and general healthcare workers (34%) suggest psychiatric and healthcare organisations should prioritise frontline healthcare workers and university students in Latin America.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis, to our knowledge, provides the first pooled estimates of mental health symptoms among key demographic groups during the COVID-19 crisis in Latin America. The meta-analytical findings of this study underscore the high prevalence of mental health symptoms in Latin Americans during the COVID-19 crisis. Hence, we call for more research to identify people vulnerable to mental health symptoms to enable evidence-based medicine during the pandemic.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000767

Data

The meta-analysis does not use primary data. All the secondary data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J. C., upon request.

Author contributions

S. X. Z.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. K. B.: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. W. X.: Investigation (Data). T. L.: Investigation (Data). R. K. D.: Investigation (Data). AY: Investigation (Data). A. D.: Investigation (Data), Writing – review & editing. B. Z. C.: Investigation (Data). R. Z. C.: Investigation (Data). S. M.: Investigation (Data). X. W.: Investigation (Data). W. Y.: Investigation. Resources J. C.: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Visualisation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Financial support

Jiyao Chen has received research support from the College of Business, Oregon State University.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.

Transparency declaration

The corresponding author affirms this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported. No important aspects of the study have been omitted and any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Patient and public involvement

No patient or public was involved in this systematic review and meta-analysis.