If Milton had written in Italian he would have been, in my opinion, the most perfect poet in modern languages; for his own strength of thought would have condensed and hardened that speech to a proper degree.

Horace WalpoleFootnote 1Winton Dean described Handel's L'Allegro, il Penseroso, ed il Moderato of 1740, hwv55, as ‘perhaps the profoundest tribute Handel ever paid to the land of his adoption’.Footnote 2 Its first two parts were comprised exclusively of texts from the paired odes L'Allegro and Il Penseroso written in 1645 by John Milton, ‘England's national poet’,Footnote 3 while the third part, Il Moderato, was an original contribution by Handel's librettist Charles Jennens. Ruth Smith has noted that it is Handel's ‘only full-length setting of English words that derive from no continental European text, either biblical or classical’, and it was premiered in a season, 1739–1740, that consisted solely of English-texted works.Footnote 4 The first revival of L'Allegro in the following season was promoted on 31 January 1741 in the Daily Advertiser as having ‘several new Additions’,Footnote 5 and a surviving copy of the wordbook from this January revival (Figure 1) confirms that Handel, somewhat surprisingly, included in this quintessentially English piece five arias and two accompagnati with Italian texts.

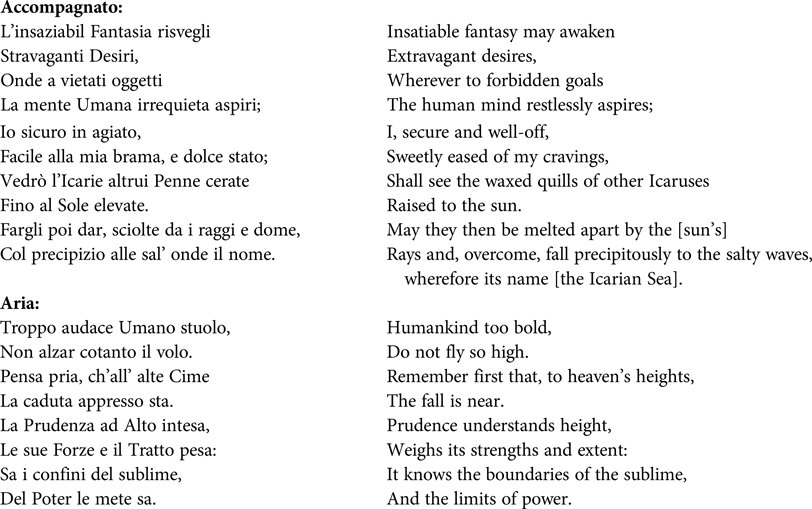

Figure 1 Italian texts in the January 1741 L'Allegro wordbook. L'Allegro, Il Penseroso, ed Il Moderato. In Three Parts. Set to Musick by Mr. Handel (London: J. and R. Tonson, 1741). Manchester Public Lirary, BR310.1 Hd578. Used by permission of the Manchester Public Library

As in many of Handel's macaronic oratorio revivals from 1732 onwards, the initial motivation for this was pragmatic: providing for a cast that included Italian singers who performed awkwardly, if at all, in English. We are fortunate to have a first-hand account of Handel's accommodation of his Italian singers for this first revival of L'Allegro. Charles Jennens describes the situation to James Harris, who arranged Milton's texts, in a letter of December 1740:

I know you will wish some of [the additional musical numbers] had been in chorus; but [Handel] was positive against more chorus's, having three new singers to provide for, Andrioni, Sigra Monsa, and Miss Edwards. I am afraid this entertainment will not appear in the most advantageous light, by reason of the mixture of languages: for though he has set Milton's English words, some of ’em must be translated by Rolli into Italian for Andrioni: Monsa will sing in English as well as she can.Footnote 6

The evidence from the performing scoreFootnote 7 clearly confirms Jennens's account: Handel first composed most of the ‘additions’ to the January 1741 L'Allegro to Milton's English texts, and only later pencilled the parodied Italian texts for the soprano castrato Giovanni Battista Andreoni's numbers into the performing score above the staff.

Jennens's letter is useful not only in confirming the reason and relative timeline for Handel's revisions to L'Allegro, but also the identity of the otherwise anonymous author of the Italian texts: Paolo Rolli. Rolli was an artistically appropriate choice for the task for several reasons. Having recently renewed his professional collaboration with Handel in the wake of the collapse of the Middlesex opera company, he had just provided the composer with a libretto for Deidamia, which Handel premiered only a few weeks before this bilingual revival of L'Allegro, so Rolli was presumably an available and a proven collaborator. Rolli was also recognized by his literary contemporaries, even his erstwhile rival Metastasio, as a particularly skilled ‘improvvisatore’ or spontaneous improviser of sung verse,Footnote 8 just as Handel was known for his musical improvisations at the harpsichord and organ.

Perhaps most importantly, Rolli also happened to be an internationally recognized translator of Milton, at a time of increasing Continental interest in the poet, especially his epic Paradise Lost. Translations of Paradise Lost had already appeared in Dutch in 1728 (Jakob van Zanten), in French in 1729 (Nicolas-François Dupré de Saint-Maur) and in German in 1732 (Johann Jacob Bodmer).Footnote 9 In 1728, Voltaire's 1727 Essay on Epick Poetry, in which he ranked Milton amongst the great epic poets, was subsequently released in France in a translation by Desfontaines, followed by Voltaire's own translation in 1733. Rolli's own translation of Paradise Lost, the first to be published in Italian and a labour of love for the poet,Footnote 10 was begun in 1717 and finally printed serially between 1729 and 1735 in London and Verona, and complete in Paris in 1740.Footnote 11

A portrait of Rolli (Figure 2) holding and pointing to a Jan Van der Gucht engraving of Milton, which featured as a frontispiece on all publications of Rolli's translations of Paradise Lost, further testifies to the high regard Rolli had for both Milton and his own translation in the context of his life's work. Franca Sinopoli notes the important role of Rolli's Paradise Lost translation, as well his defence of Milton against Voltaire's occasional criticisms in his Remarks upon M. Voltaire's Essay on the Epick Poetry of the European nations (1728),Footnote 12 in forming Rolli's identity as a ‘polyvalent’ and ‘transnational’ figure actively participating in the continuing and active ‘literaria Respublica’ in the first half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 13 One could therefore speculate that, in December 1740, Rolli might have welcomed the unexpected invitation from Handel to prepare Italian parody texts of excerpts from Milton's twin lyrical poems of 1645, L'Allegro and Il Penseroso.

Figure 2 Portrait of Paolo Rolli pointing to an engraving of Milton, attributed to Domenico Pentini. Istituto Tecnico Agrario Ciuffelli, Todi, Italy

While Handel's adaptation of his English-texted vocal lines to Rolli's new Italian texts is worthy of a study in itself, this article will instead focus on a particularly serendipitous product of Handel's use of new Italian-texted material in this first revival of L'Allegro: a completely new accompagnato and aria for Andreoni that features original Italian texts by Rolli on the subject of the flight and fall of Icarus. In a number of ways, this quasi-operatic mini-scena can be viewed as a career retrospective and artistic manifesto on fame and freedom for both composer and librettist.

‘TROPPO AUDACE’: THE TEXT

While no longer found in the performing score, the Icarus scena is extant in both an autograph and a secondary source.Footnote 14 According to the wordbook, the accompagnato–da capo aria sequence – in effect a mini-operatic scena – was performed by Andreoni near the very end of the oratorio, directly before the final chorus, No. 40, ‘Thy pleasures, moderation give’. The wordbook prints Rolli's Italian textFootnote 15 as below, without any English translation, but I give my own translation opposite:

The Icarus myth referred to by Rolli is, of course, Ovid's treatment in book 8, lines 223–234 of the Metamorphoses, given here below in Latin, then in a 1717 translation by Samuel Croxall (a member of the Kit-Kat club, which included Dryden, Gay and Congreve, all of whom had had texts set by Handel and who jointly contributed to this translation):

Rolli refers to Ovid's account in several ways. The first lines of Andreoni's aria (‘Troppo audace Umano stuolo, / Non alzar cotanto il volo’) echo Ovid's line 223 (‘cum puer audaci coepit gaudere volatu’) (my italics), and Rolli has, like Horace, chosen to describe Icarus’ wings metonymically as ‘penne’ (Latin ‘pennas’ = quills or feathers) rather than ‘ali’ (Latin ‘alas’ = wings). Rolli's closing reference in the recitative to the etymology for the Icarian sea is a final nod to Ovid's own ending of the story.

Rolli's choice of Icarus’ tragic rejection of moderation for his new L'Allegro text not only adheres to Jennens's theme of moderation in the third part, but has the additional virtue of presenting a colourful narrative just where it may have been needed, given the somewhat mixed reception Il Moderato received on its premiere the previous season. In a February 1742 letter to Edward Holdsworth, Charles Jennens himself relates that

a little piece I wrote at Mr. Handel's request to be subjoyn'd to Milton's Allegro & Penseroso, to which He gave the Name of Il Moderato, & which united those two independent Poems in one Moral Design, met with smart censures from I don't know who. I overheard one in the Theatre saying it was Moderato indeed, & the Wits at Tom's Coffee-house honour'd it with the Name of Moderatissimo. But the Opinion of many others, who signify'd their approbation of it in Print as well as in Conversation, together with the account Mr. Handel sends me of its Reception in Ireland, have made me ample amends for those random expressions of Contempt, if I wanted any amends.Footnote 18

Handel had indeed earlier reassured his friend Jennens from Dublin, writing on 29 December 1741 that ‘I opened with the Allegro, Penseroso, & Moderato, and I assure you that the Words of the Moderato are vastly admired’.Footnote 19 While Ruth Smith has argued convincingly in several articlesFootnote 20 that the text of Il Moderato resonated with mid-eighteenth-century sentiments and thus found favour with many in Handel's audience, she has also called Handel's kind words to Jennens ‘possibly the politest sentence that Handel ever wrote’.Footnote 21

Before these Dublin performances of L'Allegro, and only two months after inserting the Italian-texted numbers, Handel had revived the work again in London, removing Jennens's Il Moderato entirely and replacing it with his earlier 1739 Song for St. Cecilia's Day (hwv76), with its text by Dryden. After again restoring Il Moderato for the Dublin performances in December 1741 and March 1742, Handel replaced it once more with the Song for St. Cecilia's Day for all subsequent revivals (1743, 1754 and 1755). This series of changes suggests that Handel was of two minds about Il Moderato, and certainly the fact remains that Handel's settled version of L'Allegro eliminated the Jennens-texted original third part, despite any personal feelings he may have had for its music and text or for his friend Jennens. Might we discern in hindsight, in this new Italian scena inserted near the very end of a possibly weaker (or at least less appreciated) last third of the ode in its first revival, an attempt by Handel, with the help of Rolli, to invoke greater interest in a largely ‘Moderatissimo’, non-Miltonic final portion of the oratorio?

Smith observes that Jennens's text for Il Moderato is a classic eighteenth-century example of imitatio, in which poets simultaneously imitate and improve upon older literary forms. She notes that ‘readers were expected to recognise the model that was being imitated and to have it in their minds while they were reading’.Footnote 22 This would have been even more explicit for the listener-readers of Handel's L'Allegro, since Jennens's Il Moderato was not only an imitatio of Miltonian and Horatian odes, but also an intertextual imitatio of Parts One and Two of the musical work itself.Footnote 23 Rolli's new Italian texts build on this intertextuality, generating an even more intriguing web of literary associations, both biographical and historical, including an equally complex case of imitatio, since they recall multiple poetic precursors that are themselves part of a chain of poetic echo and allusion.

As noted above, Rolli's most obvious model is Ovid. However, the Icarus myth had over the centuries acquired a rich history as a literary topos, in classical (Ovid, Horace, Lucretius, Virgil), medieval (Chaucer, Dante, BoccaccioFootnote 24) and Renaissance (Petrarch, Shakespeare, Marlowe, Petrarch, Tasso, Ariosto, Guarini, Spenser, Dryden and Milton and others) drama and poetry.Footnote 25 The works of most if not all of these authors would have been known to Rolli. While never translating the Aeneid, he published a translation of Virgil's Eclogues in London in 1742, a year after the L'Allegro texts,Footnote 26 so he may have had Virgil in his ear. He had previously edited an Italian translation of Lucretius’ De rerum natura (1717), and had written dedications and annotations for several editions of Boccaccio's Decamerone (1725) and Guarini's Il pastor fido (1737).Footnote 27 Tasso, Spenser and Milton are discussed and defended liberally in Rolli's 1728 Remarks upon M. Voltaire's Essay, while he provided annotations for a frequently reprinted edition of the Satire e Rime of Ariosto in 1732.Footnote 28 Rolli's synthesis of literary traditions evident in the Remarks, as well as citations from Shakespeare, Petrarch, Chaucer and Boccaccio within the same paragraph in his 1729 ‘Vita di Giovanni Milton’,Footnote 29 strongly suggest that Rolli saw himself within this transnational, pan-European poetic lineage.

More specifically, however, it is Rolli's quite detailed and robust defence of Milton in the Remarks, grounded in his long-term project of producing a faithful yet poetic line-by-line translation of Paradise Lost, that is perhaps most pertinent to his contribution to the bilingual revival of L'Allegro. David Quint details Milton's use of Icarian imagery in his description of Satan's flight in book 2, lines 927–938, demonstrating how Milton's ‘poetic memory’ inspired his oblique references to Virgil's Aeneid and Lucretius’ De rerum natura.Footnote 30 The most famous Miltonian reference to Icarus’ flight may be found in the very first lines of the epic. In the invocation of his poetic Muse, Milton identifies Icarus not with Satan, but with himself (book 1, lines 12–16):

This audacious claim by Milton was obviously known to Rolli as translator of Paradise Lost. As Neil Forsyth notes, ‘Things unattempted yet in Prose or Rhyme’ is a literal translation of a line from Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, which itself is a clear reference to the first lines of Horace's Ode 3.1,Footnote 32 and is a link in a chain of less moralistic and more ambivalent allusions to Icarus in the Renaissance, not only by Ariosto and Milton but also by Tasso, Ariosto, Guarini, Sanazzaro, Tansillo and Garcilaso. Undoubtedly inspired, as Horace was, by the double meaning of ‘penne’ first used by Ovid for Icarus’ wings – which in both Latin and Italian signifies not only feather quills but also the writing pens fashioned from them – Icarus’ flight becomes a suitable allegory for the writer's attempt to channel either epic or amorous aspirations. While writers such as Christopher Marlowe (in Doctor Faustus) may have continued to use Icarus more traditionally as a prototype of demonic overreach, the myth was also reinterpreted by other poets as a necessary Promethean challenge, not only to the Gods but, perhaps more pointedly, to their human literary precursors. Milton's own invocation to his Muse suggests that the potential for failure in poetry lies not in the full-hearted pursuit of excellence but rather in its equally risky Daedalian opposite: an artistic ‘middle flight’ that is certainly competent, but half-hearted or unadventurous. In self-referentially glorifying or justifying not only their own poetic aspirations but man's artistic creations in general, Milton and others in this somewhat proto-romantic treatment of the Icarus myth simultaneously acknowledged their debt to an august literary pantheon and placed themselves within it.Footnote 33

In contrast, Rolli's Icarian texts for L'Allegro adhere to the more straightforward cautionary reading of the myth – if anything, they warn against the Horatian poetic daring of his more immediate model, Milton. His first-person narrator maintains that those poets whose pens (‘penne’) have more modest aims are the wiser, and that he himself is content to watch other poets (and perhaps musicians?) elevate (‘elevare’) themselves too high and fail. This projected poetic humility certainly accorded with the via media theme of Jennens's Il Moderato, and Rolli may have been merely following a brief by keeping to the overall theme of moderation.

Yet there is a distinct autobiographical resonance in the sentiments of his first-person narrator, for Rolli spent most of his career in the shadow of two recognizably greater poets. One was, of course, John Milton, the seventeenth-century poet still considered Britain's greatest throughout the eighteenth, called in 1734 ‘the favourite poet of this nation’,Footnote 34 in 1750 ‘the divine, the immortal Milton, the prince of English poets’Footnote 35 and in 1796 ‘the great English author’.Footnote 36 Rolli's own esteem for Milton was equally explicit and generous: he referred to Milton twice as Britain's ‘Homer’.Footnote 37 As previously mentioned, he spent seventeen years translating Milton's Paradise Lost, and also wrote the libretto for the operatic pasticcio Sabrina, based on Milton's Comus, performed by the Opera of the Nobility in April 1737 at Lincoln's Inn Fields.

The second creative shadow in Rolli's life was a fellow Italian: Pietro Metastasio. A direct contemporary of Rolli's, Metastasio was the most prolific and renowned Italian opera librettist of the eighteenth century. Responsible for hundreds of opera librettos and their variants, he became the Caesarean Poet of the Habsburg imperial court in 1729. Metastasio was perhaps unique at the time in overcoming a perception, even amongst poets, that the versification of opera librettos was unworthy, a view particularly strongly held outside the great Continental operatic centres. Giuseppe Riva, a Modenese diplomat and member of the Italian circle in London in the early 1720s, writes that ‘the operas performed in England, beautiful though they are musically and vocally, are otherwise mangled (‘storpiate’) in their poetry’.Footnote 38 Rolli himself thought the work of a librettist in London was beneath him, at one point referring to his opera librettos for Handel as mere ‘dramatic skeletons’ (‘dramatici scheletri’).Footnote 39 George Dorris suggests that Rolli ‘undoubtedly envied his former colleague [Metastasio] the position of Caesarian Poet . . . the position, wealth, and influence of Metastasio were never to be his, and this knowledge must have galled Rolli's proud nature’.Footnote 40 Dorris further describes Rolli, in his last years in London, as ‘tired and discouraged’, his lyric output reduced to a trickle and his only income derived from librettos for the Middlesex opera and occasional translations, before semi-retiring to Italy in 1744.Footnote 41

However, the text of ‘L'insaziabil fantasia’, if its first-person poetic persona can be read as a projection of Rolli himself, would suggest otherwise. The poet appears to be saying that, after a twenty-seven-year career in both Rome and London, he had not only come to terms with his poetic legacy but saw some virtue in its modesty. Rolli's ‘penna’, although not fated, like Milton's or Metastasio's, to ‘soar above the Aonian Mount’, at least provided him with a secure and comfortable living (‘sicuro in agiato’), even if it included relatively menial tasks such as providing parody texts for Handel at short notice. One could view this brief new Italian text for Handel as an attempt by Rolli to recast his career as ‘skeletal’ opera librettist and translator into a noble, skilled and moderate one, more Daedalian/Ovidian than Icarian/Horatian.

However autobiographical this may have been, Rolli's temperate outlook as expressed in the text also adhered to the tone and message of the rest of Il Moderato. Take, for example, Jennens's text for the first air in Part Three:

Come, with native Lustre shine,

Moderation, Grace Divine;

Whom the wise God of Nature gave

Mad Mortal from themselves to save.

Keep, as of old, the Middle-way,

Nor deeply sad, nor idly gay;

But still the same in Look and Gaite,

Easy, cheerful, and sedate.

While Rolli and Jennens display the expected spirit of moderation in the Augustan Age, there were also contemporary writers who instead followed Milton's lead in tracing the parallel, contradictory strain also found in Horace, which saw Icarus’ flight as a figure for artistic ambition. In the same year as the L'Allegro revivals, David Watson published a translation of Horace's Odes with annotations that give a more spirited defence of artistic pretension. Watson gives the following translation and then a commentary (what he describes as ‘The Key’) to the first fourteen lines of Ode 2.20, one of several in which Horace compares himself to Icarus:

Maecanus, I being transformed into a Swan, shall be carried through the Air on a Wing neither common nor weak; nor will I stay longer on the Earth; but, being above Envy, I will leave the Towns. Tho’ descended of poor Parents, I shall not die; I, whom you are pleased to call your dear Horace, shall never be imprisoned by the Stygian Lake . . . Swifter than Icarus, the Son of Daedalus, I will visit the Shores of the sounding Bosphorus.

The KEY:

Love of Praise is one of the strongest planted in Mankind, and Poets must be allowed a larger Share of it, as their Works are intended to last forever. If withal we consider them in the Character of Prophets singing of Futurity, they must be permitted to speak of themselves with an Air of greater Confidence and Assurance than the Generality of Writers. If the Event correspond with their Predictions, we must acknowledge that their Vanity is so much the more justifiable. Their high prophetick Character intitles them to go out of the common Road, what in others would pass for Arrogance and Self-conceit, is in them a noble Confidence in their own Abilities, or of a Talent that will bear them in their highest Pretensions.Footnote 42

If Watson is referring here to Horace as an artist ‘out of the common road’, he may as well have been referring to the third figure shadowing Rolli's career: Handel himself. The author (probably Robert Price) of the ‘Observations’ appended to John Mainwaring's Life of Handel (1760) sounds like Watson and even refers obliquely to Icarus when placing Handel in a similar category to

those who have an inventive genius [who] will depart from the common rules, and please us the more by such deviations. These must of course be considered as bold strokes, or daring flights of fancy. Such [musical] passages are not founded on rules, but are themselves the foundation of new rules.Footnote 43

It may be argued that the canonization of Handel not only closely followed the composer's death in 1759, but also the publication of Edmund Burke's watershed work on the sublime, his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), in which Burke argues that ‘the opposite extremes operate equally in favour of the sublime, which in all things abhors mediocrity’.Footnote 44 However, both Todd Gilman and Claudia Johnson have observed that Handel was referred to as a ‘sublime’ composer whilst he was still alive.Footnote 45 Johnson argues further that ‘in England, it is in the arena of Handelian commentary that the very notion of the musical sublime emerges for the first time’.Footnote 46

Gilman and Johnson also cite the satirical pamphlet Harmony in an Uproar, which predates the 1760 Observations in portraying a Handel who ‘scorn[s] to be subservient to, or ty'd up by Rules, or to have [his] Genius cramp'd’ and contrasts him with the Daedalian ‘ingenius Carpenter[s]’ who may succeed better in mere ‘Composition’. There is even a faint echo of Milton's ‘things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme’ when the pamphleteer wonders at a composer who has ‘made such Music, as never Man did before you, nor, I believe, never will be thought of again, when [he's] gone’.Footnote 47 In 1738 a statue of Handel – the first ever of a living composer – was commissioned from Louis François Roubiliac by Jonathan Tyers and erected in Vauxhall Gardens, prompting John Lockman's verses ‘High as thy genius, on the wings of fame, / Around the world spreads thy all-tuneful name’.Footnote 48

One can certainly pair a growing cult of Handel with an already established cult of Milton. Just as there was what Joshua Scodel describes as a ‘growing cult of the sublime from the mid-seventeenth century onward, exemplified in georgic and erotic literature . . . [which] provides an early instance of the now common association of great literature with imaginative extremes’,Footnote 49 Handel, according to Claudia Johnson (quoting William Hayes's 1751 Art of Composing Music), was ‘a “Man-Mountain”, and as such he towered over other composers just as Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden tower over other poets’.Footnote 50

Rolli's text for ‘Troppo audace’ does mention the sublime, but it is a sublime that has prescribed limits for the prudent (‘La Prudenza . . . Sa i confini del sublime, / Del Poter le mete sa’). However, as the concept of the sublime philosophically evolved into a category which by its very nature was ‘boundless’, examples of sublimity became a potential source of anxiety in this age of moderation. In his own overt imitatio – the Imitations of Horace (1738) – Alexander Pope characterizes a current of ambivalence in this period towards artistic daring when he criticizes the ‘people's voice’ that fails to recognize the ‘greater faults’ and ‘greater virtues’ of Spenser, Sidney, Shakespeare and, most famously, of Milton's ‘strong pinion’ that dares to elevate Satan (and level God) in Paradise Lost (book 1, lines 93–103):

In 1753 Charles Avison discussed Handel's exceptional nature in a vein of ambivalence similar to Pope's, paying Handel a backhanded compliment and again using the metaphor of flight:

Mr. HANDEL is, in Music, what his own DRYDEN was in poetry;Footnote 52 nervous, exalted, and harmonious; but voluminous, and, consequently, not always correct. Their abilities equal to every thing; their execution frequently inferior. Born with genius capable of soaring the boldest flights, they have sometimes, to suit the vitiated taste of the age they lived in, descended to the lowest. Yet, as both their excellencies are infinitely more numerous than their deficiencies, so both their characters will devolve to latest posterity, not as models of perfection, yet glorious examples of those amazing powers that actuate the human soul.Footnote 53

While Avison's partial critique of Handel's ‘incorrect’ execution, like Pope's of Milton, serves as preamble to a defence, there are other contemporary examples of praise for Handel's genius being simultaneously accompanied by accusations of overreach, in personal, artistic and commercial terms. This is consistent with much earlier reactions to Handel and his music: in April 1733 a satirical tirade against Handel appeared in The Craftsman, attributed to Rolli but most likely written by opposition politician Lord Bolingbroke. It describes the immoderate growth in an ‘insolent’ Handel's ‘Power and Fortune’, accompanied by an ‘imperious and extravagant Will . . . without the least Controul’.Footnote 54 While the real target for Bolingbroke's elaborate allegory was the overreaching first minister Robert Walpole,Footnote 55 the pretext – Handel's doubling of ticket prices for the premiere of Deborah – was still an unpopular financial decision. According to Viscountess Irvine, Handel's decision provoked a small rebellion by aristocratic silver-ticket holders who were refused admission but then ‘forced [their way] into the House . . . and carried their point’.Footnote 56

While Rolli was unlikely to have been the author of this tirade, it would have been believable, for it was common knowledge at the time that, despite Rolli's admiration for Handel, the librettist and composer had a complicated relationship. Rolli had previously become estranged from Handel as early as 1729,Footnote 57 and by the summer of 1733, the poet was instead engaged to write librettos for the rival Opera of the Nobility, formed by a group of nobleman supported by the Prince of Wales, who resented the ‘Dominion of Mr. Handel’.Footnote 58 They managed to convince not only Rolli but also Senesino and a number of other Italian singers to leave Handel's company and join theirs, on the alleged grounds of his high-handed treatment of everyone (‘Handel is become so arbitrary a prince, that the Town murmurs’Footnote 59).

In 1735, as it became clear that London could not sustain two opera companies, Sir Henry Liddell blamed the poor quality of the Opera of the Nobility's offerings on a ‘proud and saucy’ Handel who refused at that point to cut his losses and unite with them.Footnote 60 Despite a brief reconciliation of sorts after the two companies either consolidated or at least cooperated for the 1737–1738 season, Handel would soon yet again face criticism and competition from disaffected noble patrons. Margaret Cecil, Lady Brown, a fervent supporter of Italian opera in London and a patron of the Middlesex company, became involved in an organized opposition to Handel as early as 1739, when Handel had put himself in direct competition with Lord Middlesex's rival fledgling opera company by presenting a season consisting solely of oratorios.Footnote 61

The story of Handel's move from opera to oratorio in the 1730s and early 1740s, and the resistance to this move from some in his audience as he realized the new genre's artistic and economic potential, has already been detailed by numerous scholars.Footnote 62 It is precisely in the these years surrounding the L'Allegro performances that Handel's attempts to extricate himself from the influence of certain aristocratic opera patrons met with a particularly intense level of opposition and criticism. A letter in the London Daily Post on 4 April 1741 (four days before the last L'Allegro performance of the season) mentions a ‘single Disgust . . . a faux pas’ which Handel committed against certain ‘Gentlemen who have taken Offense’. The writer then makes excuses for Handel's unknown misstep as ‘the natural Foible of the Great Genius’.Footnote 63 Noting Pope's remark in the fourth book of the Dunciad, published in 1742, that Handel ‘was obliged to move his music to Ireland’ because of the aesthetic rejection of his bombastic ‘manly’ oratorio style by ‘the fine Gentleman’,Footnote 64 Carole Taylor suggests, with an apt choice of metaphor, that Handel ‘flew in the face of a gentleman's preconceived notions of how a man of his station ought to act . . . His acknowledged genius and emerging status as a cult figure confused the issue and led to attempts, groping yet often painful, to keep him in his place by means both more and less effectual’.Footnote 65

Handel himself criticized the Middlesex faction in September 1742 as ‘the gentlemen who have undertaken to middle with Harmony’.Footnote 66 An obvious pun on Middlesex and ‘meddle’, Handel's use of ‘middle’ in this context also works literally: a Miltonian critique of the ‘middle’ or mediocre way of music-making by the Middlesex opera composers. Handel's musical risk-taking can also be paired in this period with his relatively precarious financial state: Ellen Harris notes that between March 1739 and May 1743 Handel had neither a bank nor a stock account, this period being a ‘time of many changes and difficulties for Handel’.Footnote 67 Handel's entrepreneurial oratorio seasons only began to bear fruit in Dublin in the spring and summer of 1742 and subsequently in fuller oratorio seasons in London from February 1743 onwards, at which point it became increasingly clear to the ‘Quality’ that, save perhaps for the loaning of his score of Alessandro (arranged by Lampugnani as Rossane by the Middlesex opera in 1743), Handel was not willing to write new operas for Middlesex or be involved in the new opera company in any significant way. Led by Lady Brown and Lord Middlesex, aristocratic opposition to and criticism of Handel would steadily increase over the next few years, culminating in 1744 with Lady Brown organizing events to take place on the same nights as Handel's performances, and the Prince of Wales temporarily boycotting Handel's performances after the composer rejected the Prince's personal plea to write for the Middlesex company.Footnote 68

Throughout his struggle with the opera faction, it is important to note that Handel continued to receive unambivalent praise from his supporters. One defender of Handel, in an anonymous poem published around the time of Handel's 1739 performances of Israel in Egypt, portrays the composer as an oppressed genius, using biblical imagery that invites a faint, if inverted, echo of the Icarus myth. Handel is Daedalian if, like Moses, he delivers his Israelite audience through the desert via a ‘flying Muse’ (God's ‘pillar of cloud’ in Exodus 13:21). In contrast, his critics are more Icarian if, like Pharaoh's army, they are ‘quickly drown'd, / Their own dull Weight shall sink ‘em in the vast Profound’.Footnote 69 An equally glowing poem in April 1744 in The London Magazine praises Handel's setting of Milton's Samson Agonistes Footnote 70 in his oratorio Samson in terms which echo the opening to Paradise Lost: ‘Rais'd by his [Handel's] subject, Milton nobly flew, / And all Parnassus open'd to our view’.Footnote 71

Keeping in mind Handel's professional situation at the time of the January 1741 revival of L'Allegro, an examination of his music for Rolli's new texts gives ample evidence that the composer, like Milton, may have identified more with his ‘audacious’ Icarian protagonist than with Rolli's ‘secure’ and more ‘moderato’ narrator.

‘TROPPO AUDACE’: THE MUSIC

The scena opens with an accompagnato, ‘L'insaziabil fantasia’ (Example 1) that begins in G major with a descending arpeggiated seven-semiquaver figure passed from first violins to seconds to violas and bass, obviously foreshadowing Icarus’ fall. With a third-inversion B major seventh chord instead of the expected B minor in bar 5, the activity in strings and bass leads to a rapid but now expected harmonic move to E major in bar 9, followed by a calmer A minor/D major passage in bars 9–14, during which the poet/singer describes his own secure and comfortable state, accompanied by tied semibreves in the strings. However, instead of the expected circle-of-fifths progression to G major, the rising vocal line on ‘vedrò l'Icarie altrui penne cerate fino al sole elevate’ (shall see the waxed quills of other Icaruses raised to the sun) is answered in bar 16 by a leap in the first violins of a major seventh to c♯3, over a first-inversion F sharp major chord, reaching B minor in bar 18. The string lines fall first slowly in slurred quavers, then more precipitously in bars 18–19, using the opening falling-semiquaver motive, the first violins descending to a g♯ in bar 20 as Icarus falls into the ‘salty waves’ on ‘sal'onde’,Footnote 72 to finish with a slightly unstable cadence on a first inversion chord of B major in bar 21.

Example 1 Handel, accompagnato ‘L'insaziabil fantasia’, January 1741 L'Allegro, Il Penseroso, ed Il Moderato. In Three Parts. Set to Musick by Mr. Handel (London: J. and R. Tonson, 1741). GB-Lbl R.M.20.f.11, 1r–2r, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

In the next section (bars 21–30), Handel begins resetting Rolli's second quatrain, as if he (or Icarus) has had a second bout of inspiration. The singer's line rises again on the text ‘vedrò l'Icarie altrui penne cerate fino al sole elevate’ in bars 21–23, this time in E major, with violins surging upwards more insistently with dotted quavers on an arpeggiated E major seventh chord in bars 23–24. The vocal line also becomes more active, with an octave leap on ‘fino al sole elevate’, briefly reaching the expected A major in bar 25. The slurred quavers in the strings in the same bar – more conjunct than their first appearance in bar 16 – suggest that Icarus’ daring may have succeeded, and that he is temporarily enjoying his flight. However, a diminished-seventh chord over a bass A♯ in bar 26 again forecasts the imminent danger of the melting sun's rays (‘sciolte dai raggi’) and interrupts the expected circle-of-fifths progression.

Falling semiquavers in the strings return even more persistently in bar 27, the first violins falling below both seconds and violas to a low A, with a pictorial octave plunge in the vocal line on ‘precipizio’ (precipice) in bar 28. Under this, the chromatic progression in the bass in bars 23–30 (G♯–A–A♯–B–B♯–C♯) drives the rapid if troubled harmonic sequence from A major to B minor and to a final cadence, via a tonicized C sharp major chord, in F sharp minor, the mediant minor of the following aria (‘Troppo audace’, D major). The accompagnato is pictorially and harmonically exciting, and ends a world away, geographically and tonally, from the earthbound G major tonality with which it began.

Winton Dean suggested that one feature of Handel's experimental tendencies during his transitional period from opera seria to oratorio in the late 1730s and early 1740s was an avoidance of da capo arias, noting that L'Allegro has only two, both of which are ‘unorthodox examples of the technique’.Footnote 73 The first is the soprano air ‘Sweet bird’ in Part One, and the second the aria-accompagnato-da capo sequence ‘Straight mine eye / Mountains on whose barren breast’, newly written for the January 1741 revival with an English text but performed instead in Italian by Andreoni as ‘Dilettoso sol tu sei / Alte montagne’ (delightful are thee only, / high mountains), and most certainly not originally intended as a da capo. Dean was perhaps unaware of the temporary third da capo in this L'Allegro revival: ‘Troppo audace’ (Example 2), which followed the accompagnato ‘L'insaziabil fantasia’. A 6/8 Allegro in D major, it is the expected coloratura tour de force for the soprano castrato, with running semiquavers in the voice and violin which alternate between conjunct and disjunct movement, simulating Icarus’ audacious and wind-borne flight. Even when the vocal line judders (bars 37–40, 50–52) or descends slowly by step (bars 25–27, 54–55) on the text ‘la caduta appresso sta’ (the fall is near), perhaps simulating Icarus’ difficulties, the unison violins continue to soar. In a contrasting B section, Handel has made the extremely unusual choice of a change in both key and time signatures: from a two-sharp 6/8 to a one-flat 4/4.Footnote 74 Opening on a D minor chord and cadencing in A major, this contrasting section switches to four-part string writing, opening serenely and piano on the text ‘La prudenza’ (prudence). However, at the mention of ‘limits’ (‘mete’) in bar 74, the continuo begins to bristle with figures as the harmonic complexity increases, soon wrenching both sharpwards and flatwards with a series of third-inversion dominant-seventh chords. While this section appears to veer into greater harmonic extremes than either accompagnato or A section, the juxtaposition of D minor, B flat major and E major harmonies can be seen on a larger scale as minor subdominant, Neapolitan and dominant inflections of a conventional cadence in A major, preparing the da capo. Is this Handel, as happened in the accompagnato, enacting Icarus’ dangerous flight even while confidently displaying his harmonic control, ironically testing the surety of a text that extols prudence and an awareness of limits? Or is this B section instead a display of Daedalian control, testing the limits of harmony but not breaking them? This is, of course, a matter of interpretation, but I would suggest that Moderation's counsel in this B section, whether ironically undercut by the music or not, is certainly undermined by the return to an A section in a da capo in which Andreoni, with his flight of even more embellished Icarian coloratura, presents a challenge to, if not outright subversion of, Jennens's and Rolli's central message of moderation over audacity in these January 1741 performances.

Example 2 Handel, aria ‘Troppo audace’, January 1741 L'Allegro. GB-Lbl R.M.20.f.11: fols 2v–4v, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

This potential dissonance between music and text – and perhaps between librettist and composer – may be the result of the contrasting temperaments and life stories of these two ‘transnational’ artists. The image that Rolli projected as a modest poet and translator vis-à-vis both Milton and Metastasio has already been discussed, as has Handel's disdain for the ‘middling’ efforts of the Middlesex opera in the winter of 1740–1741. However, there is further textual and musical evidence to suggest that Handel's musical depiction of this Icarus scena in L'Allegro may not only be a reflection of recent events in his professional life but also a kind of retrospective – echoing, perhaps unconsciously, a musical treatment of the Icarus myth at the very beginning of his career.

The soprano cantata Tra le fiamme (hwv170) was copied in July 1707 for one of Handel's principal Italian patrons, the Marquis Ruspoli, and it most likely served as Handel's contribution to a weekly ‘quota’ of music furnished for Ruspoli in return for hospitality during his multiple stays in Rome between 1707 and 1710. The first aria of this richly scored cantata, bearing the alternative title Il consiglio, warns of the dangers of the heart's attraction to ‘fair beauty’ (‘vaga beltà’), using the commonplace metaphor of moths or butterflies burning themselves in the flame of a candle. In the succeeding recitatives and arias, the author of the text, Cardinal Pamphilj, naturally switches to the related topos of self-immolation through imprudence: the Icarus myth. Using language quite similar to that in the A section of ‘Troppo audace’, the singer warns his listener that, for those not born as birds, the ‘too bold flight’ (‘volo . . . troppo ardito’) is exhilarating but foolish, and falling is customary (‘Per chi non nacque augello il volare è portento, / il cader è costume’).Footnote 75 Both Ursula Kirkendale and Ellen HarrisFootnote 76 have suggested that this was a thinly veiled warning to Handel by Pamphilj, given rumours circulating at the time of a romance or at least attraction between Handel and Vittoria Tarquini, a soprano for whom he most likely wrote the cantata Un alma inamorata (hwv173) and who was a married mistress of Prince Ferdinando de Medici, another powerful patron of Handel's during his Italian sojourn.Footnote 77

Judith Peraino discusses a potential homoerotic reading of this particular cantata, complicating the objective moral stance of poet in relation to composer by seeing something more transgressive in Pamphilj's ‘consiglio’ or advice, especially when mapped against the Icarus story.Footnote 78 Pamphilj's admiration for the young German composer was well known and effusive, and Handel in later years told Charles Jennens that Pamphilj was an ‘old Fool’ who ‘flatter'd’ him,Footnote 79 and he perhaps needed to fend off more than mere flattery from the Cardinal during his time in Rome. For Peraino, it is the older Pamphilj rather than Handel who is in danger as an Icarus, and whose ‘dangerous attraction’ could only enjoy a ‘phoenix-like’ rejuvenation through the ‘middle-way’ sublimation of Handel's erotically charged music (Pamphilj's Arcadian nickname was Fenice Larisseo). In a musical reading of Tra le fiamme similar to mine for ‘Troppo audace’, Peraino suggests that, in the unusual indication by Handel of a return at the very end of the cantata to the initial aria depicting moths dying in erotic flames, Handel creates a ‘large-scale da capo form’ through which he ‘resurrects artist and audience and sends them on infinite flights of fancy and hubris’.Footnote 80 In responding to Peraino's reading, Ellen Harris acknowledges the potential homoerotic subtext but reinforces her earlier biographical reading by inverting Peraino's mapping, seeing Pamphilj instead as a Daedalus who, unlike the inexperienced Icarean Handel, is ‘able to return safely from any amorous liaison’.Footnote 81

Certainly, both erotic interpretations are valid, and such hermeneutical freedom is not only particularly Arcadian, but perhaps here amplified by the ambivalent status of the Icarus myth within the early eighteenth-century literary tradition already discussed above. However, explicitly erotic readings can easily distract from one that is more literal, and equally Arcadian as well as biographical. In a self-aware metaturn in the second half of the text, Pamphilj suggests that flying poetic thoughts are more sublime than the metonymic ‘feathers’ (‘piume’) of the writer's (or composer's) pen that produced them:

Pamphilj here taps into the same Horatian double meaning of ‘piume’ (feather or writing quill), as do Rolli and Milton (who uses the Latinate ‘penns’ and ‘pennons’ in Paradise Lost for feathers or wingsFootnote 83). Like Milton (but unlike Rolli), Pamphilj subscribes to the Horatian reading of the myth and suggests that high flying is indeed possible, but perhaps only through the God-given gifts of poetry and music.

Despite these textual resonances, it must be admitted that there is very little musical resemblance between Handel's earlier treatment of the Icarus myth in Tra le fiamme circa 1707 and his later 1741 Icarus scena for L'Allegro. First, there is an overall difference in tone: Pamphilj's witty text in 1707 is preponderantly amorous and is given a correspondingly lighter treatment, with a first aria that delights in the flight of moths in a lilting 3/8 scored for flutes and viola da gamba as well as strings, its delicate, amorous soundworld ironically flouting the violent imagery of self-immolation. Handel reused the opening bars in Partenope (1730, revival 1737) for the bittersweet closing number of Act 2, ‘Qual farfalletta’, in which the queen Partenope admits her conflicted love for Arsace using a similar moth-to-the-flame metaphor.

Similarly, Icarus’ doomed journey itself is only briefly described musically in the cantata using simple word-painting in the first secco recitative, with short bars of ascending running quavers for his ascent on ‘volare’ (flying) and descending dotted quavers for his descent on ‘cadere’ (falling), while the second aria, ‘Pien di nuove’, is also light, even jocose, depicting Icarus’ flight and the murmuring sea beneath him with inégal dotted quavers and triplets. The third and last aria in Tra le fiamme, ‘Voli per l'aria’, again bears a textual affinity to ‘Troppo audace’, but any musical borrowing may have been avoided by Handel as he had already put this material to new use in a reworked aria for bass, ‘Nel mondo e nell'abisso’, in Riccardo Primo (1727) and then in Tamerlano (1731).

There is, however, one kernel of musical resemblance between Tra le fiamme and the 1741 L'Allegro scena that is surprisingly fruitful. In the first aria of the cantata, Handel employs a hemiolic gesture of conjunct ascending semiquavers grouped 3 + 3 within 3/8 bars (Example 3) that also features prominently in both string and vocal writing in ‘Troppo audace’, but integrated into a compound 6/8 metre (compare Example 2, bars 1–10, 30–31 and 67–68).

Example 3 Handel, ‘Tra le fiamme’, Tra le fiamme, hwv170, bars 42–51. GB-Lbl R.M.20.d.13, fol. 2v, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

The musical resemblance between these two passages accords with the pictorial: in ‘Tra le fiamme’, the coloratura occurs on ‘bel-TÀ’, perhaps depicting the flames of beauty which deceive and lead moths to their death, while in ‘Troppo audace’ Handel sets it to either ‘au-DA-ce’ or ‘al-ZAR’, enacting Icarus’ audacious and dangerous flight. It is worth comparing this with Handel's use of an almost identical motive in ‘Non le scherzate’, the first aria from Udite mio consiglio (hwv172), another early Italian cantata probably written around the same time as Tra le fiamme (Example 4).

Example 4 Handel, ‘Non le scherzate’, Udite il mio consiglio, hwv172, bars 9–30. GB-Lbl R.M.20.d.12, fol. 2v, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

One of Handel's earliest, it was recopied for the Marquis Ruspoli in May 1707, and, like Tra le fiamme, it features a narrator who warns those shepherds who are ‘inexperienced in love’ (‘inesperti d'amor pastori’) of the seductive qualities of a particular little shepherdess (‘picciola pastorella’) who is as cruel as she is false and sly (‘È al par di lei cruda fallace e scaltra’). Comparisons with ‘Troppo audace’ become even more interesting in the B section of ‘Non le scherzate’, which, like ‘Troppo audace’, changes to 4/4 time and also opens rather unusually on a parallel-minor chord before some similar harmonic wandering takes place. Could Handel, in consulting his copy of Tra le fiamme when he was composing the L'Allegro scena in late 1740, have also come across (and been inspired by) this other early ‘consiglio’ cantata?

Handel used such triple-metre hemiolic gestures in various permutations throughout his vocal writing – for example in an Act 2 aria for Unulfo in his 1725 opera Rodelinda (‘Fra tempeste’), two arias from Deidamia (‘Si, m'appaga’ and ‘Come all'urto’) that premiered only weeks before this revival of L'Allegro, and an alto aria from Messiah (‘O thou that tellest’), written the following summer (Examples 5–8).Footnote 84 Of these four, only ‘Si, m'appaga’ from Deidamia has potentially pejorative connotations. Achilles pretends to reject the pursuit of love in favour of the hunt, the hemiola figure enacting the broken promises of women (‘ch'ei promette e poi non dà’), but given the generally lighter tone of Deidamia, it could be construed as being delivered in an equally light-hearted, ironic vein. The other three arias that use this figure, however (‘Come all'urto’, ‘Fra tempeste’ and ‘O thou that tellest’), are unequivocally positive, and, like the Icarus scena, use water metaphors (torrents, storms) and height or upward movement (ascending a hill or mountain, a star breaking through clouds) to refer respectively to a military triumph, the optimistic resolution of a crisis and the arrival of the Messiah.

Example 5 Handel, ‘Fra tempeste’, Rodelinda, hwv19, Act 2, bars 88–99. GB-Lbl R.M.20.c.4, fols 48v–49r, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

Example 6 Handel, ‘Si, m'appaga’, Deidamia, hwv42, Act 2, bars 90–97. GB-Lbl R.M.20.a.11, fol. 55r, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

Example 7 Handel, ‘Come all'urto agressor’, Deidamia, hwv42, Act 3, bars 94–101. GB-Lbl R.M.20.a.11, fol. 67r, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

Example 8 Handel, ‘O thou that tellest’, Messiah, hwv56, Part One, bars 3–12. GB-Lbl R.M.20.f.2, fol. 22v, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

There are further striking similarities between the Messiah aria ‘O thou that tellest’ and ‘Troppo audace’, despite a difference in tempo markings (a difference arguably negligible in actual performance). They share not only the hemiola figure in both string and vocal writing but also a D major key, a 6/8 metre and a descending scale of quavers in the voice from b1 to a held c♮1. Most interesting is a shared flirtation with the subdominant via its dominant seventh over a pedal d/D in the bass under upper-string harmonies outlining a dominant-seventh chord, which in both cases only briefly resolves to G major before returning to the tonic D major (Examples 9a and 9b).

Example 9 (a) ‘Troppo audace’, bars 54–57; (b) ‘O thou that tellest’, bars 90–93. GB-Lbl R.M.20.f.2, fol. 24r–24v, transcription Lawrence Zazzo

In ‘Troppo audace’, Handel sets this gesture to the ominous text ‘la caduta appresso stà’ (the fall is near), but in the Messiah aria it is the triumphant ‘glory of the Lord’. This stark contrast between texts is either a case of Handel redeeming profane material in L'Allegro for sacred use in Messiah, or, as argued here, the reverse: if we read the exultant jubilant energy of ‘O thou that tellest’ back into ‘Troppo audace’, it strengthens a case that Handel's musical rejoicing in Icarus’ flight indicates at the very least some dissonance with Rolli's cautionary Icarian text.

When suggesting links between such potentially generic figures, used not only by Handel but other composers of the period, one must proceed with caution. However, I would like to suggest that this chain of musical resemblances between c1705 and 1741, goal-posted by two similar Icarian texts as well as significant events in the composer's life, may not be merely accidental, but a musical representation, however unconscious, of a current in Handel's professional and personal lives. The composer appears to have followed Pamphilj's advice, and that of the unknown writer of Udite il mio consiglio, on both romantic and artistic fronts. He never married, and there is no record after Vittoria Tarquini of any romantic relationships, despite continuing curiosity and speculation on the part of Handel scholars. Whatever relationships Handel had, if any, were remarkably discreet. In terms of patronage, when Handel left Italy he also left behind his weekly musical ‘quota’ for the Marquis of Ruspoli, who is curiously never mentioned by Handel, or by Mainwaring, Handel's earliest biographer. Instead, Mainwaring remarks on Handel's ‘noble spirit of independency, which possessed him almost from his childhood . . . never known to forsake him, not even in the most distressful seasons of his life’.Footnote 85 Handel did find in England the ideal royal patrons – first Queen Anne and then the two Hanoverian Georges and their families – who combined generous financial subsidies with enthusiastic artistic support and, in the case of the princesses, even mutual affection. Awarded a series of pensions and salaries which amounted to £600 per year from 1723,Footnote 86 his positions as Music Master to the royal children and Composer of Musick were relatively light-touch posts that simultaneously gave Handel some measure of financial stability (Rolli's ‘sicuro in agiato’) whilst allowing him to exercise his ‘noble spirit of independency’ in pursuing his adventurous and often loss-making operatic and oratorio seasons in London.

CONCLUSION

Handel and Rolli's brief Italian scena for Andreoni in the January 1741 revival of L'Allegro serves as a fascinating intersection of the biographical, the literary and the musical for both composer and librettist, while also serving as a snapshot of mid-eighteenth-century attitudes towards Milton. Despite setting a number of Milton's texts, including not only L'Allegro but also Samson Agonistes (Samson, 1743) and some of the poet's Psalm paraphrases in the Occasional Oratorio (1746),Footnote 87 Handel never took up the obvious opportunity to write an oratorio based on Milton's most famous work, Paradise Lost, despite numerous opportunities.Footnote 88 Instead, in these ephemeral Italian texts and music written for the first and only bilingual revival of L'Allegro, one cannot help but see both Handel and Rolli enacting their own brief but clear imitatio of Paradise Lost. If Rolli here humbly pays homage not only to ‘il britanno Omero’ – Milton – but also to Milton's greatest musical interpreter, ‘il caro Handellino’, Handel's musical setting remarkably manages simultaneously to fulfil yet Miltonically challenge the moderating warning of Rolli's text.

‘Troppo audace’ was almost certainly the last text for new music that Rolli would provide for Handel and – while he may not have realized it at the time – it was also Handel's last new Italian-texted composition for solo voice.Footnote 89 While Handel was entering what were arguably his golden years of English music drama, Rolli would only a few years later retire to his inherited ancestral home of Todi, living a quiet and financially comfortable (‘sicuro in agiato’) twenty more years until his death in 1765. Other than a translation of Racine's Athalie,Footnote 90 his one last large publication was a collected edition of the opera librettos he had written earlier for Handel, Porpora and others during his London years.Footnote 91

Given the lack of an English translation in the wordbook and its removal from subsequent performances, Rolli and Handel's original contribution to the January 1741 L'Allegro was most likely lost on most of the oratorio public at the time. Born out of a need to accommodate a castrato's linguistic limitations and perhaps rescue a too-moderate Il Moderato, its ephemeral nature has also possibly contributed to its relative neglect by Handel scholarship until this study. Yet the ‘Troppo audace’ scena is not only a fitting farewell by Rolli to both Milton and Handel and a snapshot of their respective situations c1741, but also a career manifesto, in quite different ways, for composer and versifier. In a Handel making a transition from his already sublime achievements in opera to the Icarian ‘daring flights of fancy’ of oratorio, and in a Rolli making his slow Daedalian descent after a varied but still successful career as member of the transnational European republic of belle lettere, we see these two artists here briefly play out an intersection of the complementary contradictions of moderation, ambition, imitation and freedom in music and poetry in the middle (but not ‘middling’) eighteenth century.