Georg Philipp Telemann, Johann Sebastian Bach and their German contemporaries were among the first to write polonaises with any regularity, and the dance tended to appear in keyboard and orchestral suites as an extra ‘galanterie’ adding local colour to the selection of dances.Footnote 1 This raised interest in the polonaise during the eighteenth century was apparently due to composers’ desire to cultivate Polish patrons and to provide exotic dances to audiences more familiar with the French, Italian and German styles.Footnote 2 Recent studies of the adoption and assimilation of the Polish style in the instrumental music of Telemann and in the vocal music of J. S. Bach have highlighted rhythmic and melodic features associated with this ‘barbaric’ idiom as well as illuminating its broader cultural implications.Footnote 3 Telemann's interest in the music of Poland came initially from his first-hand encounters with Polish music while Kapellmeister in Sorau (1705–1708). In the case of Bach, the stimulus was the importance of the Polish style at the Dresden electoral court. The Elector of Saxony (also King of Poland) encouraged the performance of Polish music at court in Warsaw and Dresden, and by the mid-eighteenth century the dance, known as the danse aux lumières, had a particular place in Dresden courtly and civic life. Charles Burney was moved to write in 1772 that ‘Musical airs, known by the name of Polonaises, are very much in vogue at Dresden, as well as in many other parts of Saxony; it is probable, that this was brought about during the long intercourse between Poles and Saxons, during the reigns of Augustus the Second and Third.’Footnote 4 Szymon Paczkowski has not only established the use of polonaise rhythms and cadences in movements of the B minor Mass, but has also pointed out the pragmatic reasons why Bach incorporated elements of this style in music accompanying his application for the position of Dresden court composer in 1733, and why he included arias in polonaise style in cantatas dedicated to high-ranking appointees of the Saxon Elector, such as the City Governor of Leipzig.Footnote 5 However, as Peter Wollny has pointed out, the early history of the dance remains largely unexplored.Footnote 6

The principal contexts for the polonaise in eighteenth-century Dresden were courtly entertainment and masked balls (Redouten). While the processional polonaise was apparently part of courtly life in Dresden by the turn of the eighteenth century, the earliest detailed report of such a procession comes from the wedding of Prince Friedrich August (the future August III) and Maria Josepha von Habsburg on 4 September 1719:

The King . . . with the Queen opened the ball to the strains of magnificent music, to which a Polish dance was performed, dames and cavaliers[,] couple after couple[,] following the King. In front of the King walked four Marshals with their staffs, and since this took half an hour, the royal personages and their ladies round about sat down again; after this the Electoral Prince invited his bride to dance a minuet. . . . There were also English and German dances.Footnote 7

Such was the popularity of the dance, right up to the end of the Saxon monarchy in 1918, that ceremonial balls at the Dresden court usually commenced with a polonaise.Footnote 8 The polonaise was also popular in civic life at the fashionable Redouten, which appear to have been important features of the Dresden social calendar from the 1720s to the 1770s. Commercially produced manuscript sets of orchestral minuets and polonaises, created for use in specific years in the Redoutensäle, were advertised by the Breitkopf firm between 1761 and 1780 (Table 1).

Table 1 Collections of Redouten performed in Dresden, 1749–1779

Notes

a Verzeichniss Musicalischer Werke, allein zur Praxis, sowohl zum Singen, als für alle Instrumente, second edition (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1764). Here and below, ‘NT’ indicates a non-thematic catalogue.

b Johann Baptiste Georg Neruda (1711–1776) was a Czech composer and violinist. In 1741–1742 he entered the service of Count Rutowski in Dresden and then from 1750 to 1772 was Konzertmeister of the Dresden Court Orchestra. While there is no reference to the Redoute in the title of Becker III.8.56, the date in the title, unusual in manuscripts of the period, indicates an association of these ‘balli’ with an annual event. In addition, this set of dances appears to be an arrangement of orchestral works and is is preserved amongst other arrangements of Redoutentänze, such as those for the following year by Roellig and Knechtel.

c The same copyists are responsible for the Neruda, Roellig and Klipfel collections in D-LEm, and these manuscripts all originated at the Breitkopf firm (my thanks to Peter Wollny for confirmation of this point).

d Little is known of Johann Georg Knechtel (born c1710). In about 1734 he succeeded Johann Adam Schindler as first horn in the Dresden court orchestra, remaining in this position until 1756, when he transferred to cello and continued performing until 1773. In addition to sets of minuets and polonaises in Schwerin and Leipzig, twenty-five polonaises were published in London by Cox (RISM A/I K980).

e The source, anonymous and tentatively dated 1770–1800 in RISM, has been ascribed to Georg Gebel (1709–1753), presumably since the previous items in the bound collection, consisting of some minuets and polonaises ascribed to Gebel, are in the same copying hand. However, the 1755 polonaises are on different paper and postdate Gebel's death. Thus the attribution to him must be deemed doubtful, and the dances will be referred to below as the ‘Gebel’ set.

f Johann Adam (c1705–1779) was a Jagdpfeifer (hunt-piper) at the Dresden court from 1736, then a violist in the Hofkapelle. From c1740 he was ‘ballet-compositeur’ of the court opera and composer and director of the French theatre (1763–1769). He composed ballet music for Hasse operas and in 1756 published a Recueil d'airs à danser executés sur le Théâtre du Roi à Dresde, arranged for harpsichord. He is the probable author of the orchestral and chamber works attributed to ‘Adam’ in the Breitkopf catalogues.

g Simonetti may be J. A. Simonetti or, more likely, Johann Wilhelm Simonetti, who composed a violin concerto preserved in Dresden and Frankfurt.

h Supplemento II. Dei Catalogi della Sinfonie, Partite, Overture, Soli, Duetti, Trii, Quatri e Concerti per il Violino, Flauto Traverso, Cembalo ed altri Stromenti (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1767). This and other Breitkopf thematic catalogues are reprinted in The Breitkopf Thematic Catalogue: The Six Parts and Sixteen Supplements, 1762–1787, ed. Barry S. Brook (New York: Dover, 1966).

i Verzeichniss Musicalischer Werke, allein zur Praxis, sowohl zum Singen, als für alle Instrumente, third edition (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1770).

j Music is lost. A movement from this set might well be the ‘Fackeltanz’ in Berlin copied in 1886: ‘Fackeltanz | a | due Corni | due Oboe | due Violini et | Basso | Del Sig: Adam | ist bey der Vermählung des | Königs Friedrich August als Curfürst | Anno 1769 von den König Camer | Musici gespielt worden’.

k Hennig may be Christian Friedrich Hennig, Kapellmeister at Sorau (fl. c1760–1775) and composer of divertimenti preserved in Dresden and Leipzig.

l Verzeichniss Musicalischer Werke, allein zur Praxis, sowohl zum Singen, als für all Instrumente, fourth edition (Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1780).

m Possibly Johann Christoph Richter (1700–1785), organist and composer based in Dresden. He was appointed court organist at seventeen and served as the court's cantor from 1751 to 1785. He learned to play the pantaleon from Pantaleon Hebenstreit.

There were four other contexts in which instrumental polonaises were composed.Footnote 9 First, there are collections of keyboard polonaises by Johann Gottlieb Goldberg (also attributed to Johann Gottfried Ziegler) and Wilhelm Friedemann Bach designed to be performed in concert or private contexts during the period c1754–1770.Footnote 10 In collections such as these, composers often use the polonaise to explore a spectrum of affects and keys in a systematic way, in the manner of earlier preludes and fugues.Footnote 11 Works such as Friedemann's Twelve Polonaises, Fk12, written in Halle c1763, not only require an advanced technique, but are sophisticated works far removed from the polonaise's folk origins, a point to which I will return.Footnote 12 There were also compilations of pre-existing single works garnered from various sources for domestic performance, often in a simpler style suitable for amateurs.Footnote 13 Among these are manuscript compilations of single movements by multiple composers, many anonymous and often copied from larger multi-movement works, preserved in the Becker collection in the Leipzig Stadtbibliothek.Footnote 14 Similarly, Princess Maria Anna Sophia of Saxony (1728–1797), daughter of Augustus III, collected over 350 polonaises.Footnote 15 Second, polonaises often appear in pedagogical collections, such as J. S. Bach's 1725 Clavier-Büchlein and the various volumes published by Breitkopf as ‘Kleine Stücke aufs Clavier für Anfänger’.Footnote 16 Third, polonaises or alla polacca movements appear in symphonies that precede homage cantatas for members of the Wettin family, such as those composed by Johann Christian Roellig and performed by the Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum.Footnote 17 Finally, concluding polonaises defined a subgenre of ensemble partita that was extremely popular in Dresden in the 1740s to 1760s and closely associated with the Kapelle of Count von Brühl. The most prolific composer of the ‘Dresden partita’ was Roellig, who composed over sixty examples in a variety of instrumentations from solo keyboard to orchestra.Footnote 18

Roellig, whose older brother Johann Georg was organist at the court of Anhalt-Zerbst, was born in 1716 in Berggieshübel and attended the Dresden Kreuzschule. Thereafter, little is known of the composer other than that he appears to have been an itinerant freelance musician in the Dresden–Meissen area before moving in about 1763 to Hamburg, where he was associated first with the Ackerman opera company as co-repetiteur (from 1764 to 1773) and then as Kapellmeister to Graf Ernst von Schimmelmann, a post he very probably maintained to the end of his life (c1780). He was befriended by the amateur musician and collector Carl Jacob Christian Klipfel (1727–1802), a Meissen porcelain artist and later co-director of the Berlin Porcelain Factory (Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur), who commissioned numerous musical works for the Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum. Over 160 works by Roellig, representing ninety-five per cent of his extant oeuvre, are preserved in the Klipfel collection, which was amalgamated into the holdings of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin around 1810.Footnote 19 Roellig was a prolific composer of symphonies and partitas, and his music epitomizes the mid-century galant idiom prevalent in Dresden, particularly in slow movements. Influence of the emerging Viennese classical style is also apparent in later works.

Roellig's music provides the largest surviving repertory of Dresden polonaises by a single composer, encompassing dances in at least three collections for Redouten, in partitas and divertimenti composed c1740–1763 and in symphonies preceding homage cantatas. This repertory is notable for its formal variety and also for the inclusion of the mazur (mazurka), an early use of this dance type in music by a German composer. In what follows, I examine the social contexts of the mid-century polonaise in Dresden before turning to the style and structure of Roellig's examples in particular.

THE DRESDEN REDOUTEN: CONTEXT AND REPERTOIRE

Dancing was a popular pastime in Dresden in the eighteenth century. Whereas outdoor concerts (Gartenkonzerte) were popular in the summer months, on winter evenings the dance culture thrived, ‘since the local sprightly folk do not despise Terpsichore's pleasure, so there are many dance halls, dance rooms and dance parlours [in Dresden]. . . . Of the halls, the most visited is Perini's, and the most beautiful is the Hotel de Pologne’ (‘Da das hiesige muntre Völkchen Terpsichore's Freuden keineswegs verachtet, so giebt es auch ein Menge Tanzsäle und Tanzzimmer, und Tanzstübchen. . . . Von den Sälen ist der besuchteste, der bei Perini; der schönste im Hotel de Pologne’).Footnote 20 Redouten were first established in the electoral palace in the early eighteenth century, and commercially organized balls had become popular in the city by mid-century. In 1744 the balls took place in a house in the Pirnische Gasse, while by 1750 they were promoted at both the Hotel de Saxe and the Hotel de Pologne, as well as at private functions. Between mid-January and Shrove Tuesday, during the carnival season, as many as twenty-six balls would take place.Footnote 21 By 1729 masked balls occurred weekly on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays, and then nightly in the final week leading up to Shrove Tuesday.Footnote 22 Redouten continued unabated through the Seven Years War (1756–1763), and in 1761 masks were dispensed with for the first time.Footnote 23

Music at the earliest balls consisted of ‘Menueen und teutsche auch Engl[ische] Tänze mit Violine’ (Menuets, Teutsche and English dances with violin),Footnote 24 but the stately processional polonaise customarily heard at the beginning and end of courtly balls also became one of the main features of civic Redouten. The main purpose of the courtly polonaise was to offer an opportunity to the lady in whose honour the ball was given to greet guests and invite them to participate in the entertainment. Thus the sequence of multiple polonaises provided a ritual entrance or, when it was performed at the end of the evening, an exit to the proceedings, when farewells replaced greetings. The couples progressed in line, with gliding steps accented by bending the knees slightly on every third step (on the final beat of the bar), waiting to be presented to the host.Footnote 25 Clearly a single binary dance would not provide enough music for such a ritual, and so composers provided a chain of dances in a collection.

There was a formality to the dancing of the polonaise: ‘Two bows were usually done, each taking up one bar of the music, with the first to the public, the second to the lady, much in the same manner as the minuet.’ Then ‘the general carriage of the body should be stretched and pulled up with the sternum lifted, thereby creating a pigeon-chested effect’.Footnote 26 The only detailed description of the eighteenth-century polonaise and its step, the pas de polonaise, is found in Christoph Gottlieb Hänsel's 1755 ballroom manual Allerneueste Anweisung zur aeusserlichen Moral.Footnote 27 Couples promenaded around the ballroom led by the male partner to the left, the lady with her hand (in the ‘Polish style’) placed on her partner's right palm, which was stretched in front of him, moving with steps described by Hänsel as a bourrée tombeé. Footnote 28 Hänsel, according to Donna Greenberg, comments that ‘when the Germans dance, the gentlemen often let the lady's hand go, so that the separated couple could perform different variations in the figure, with one in front, or behind the other, for example, arranged in a straight line or in a serpentine manner, in the manner of a hey; the men could then dance from the bottom to the top of the line[,] weaving in and out until each dancer reaches his lady again. Then they might dance around in a circle, and then the ladies could do the same as the men’.Footnote 29

There appears to have been a marked difference in the manner of the dance as perceived by native Poles and as executed by the dancing public in Germany. Hänsel explicitly remarks upon the lack of consensus in movement amongst German dancers: ‘The true polonaise is indeed something splendid, especially when the step is executed in a regular and precise manner to the music, at a moderate speed and with gentle bearing. Indeed it is, as I have given it here, but it is to be lamented that taste differs so greatly. . . . One comes across ballroom dancers who all fancy that they know how to do the pas de polonaise correctly, but they are for the most part charlatans, and it is not our intention to enter into a quarrel with them.’Footnote 30 The processional Polish dance was marked by a certain gravity, and in Hamburg in 1783 it was described as a ‘proud walk’ consisting of

lauter majestätischen Schritten, drey auf einem Tact; mit unter kommen dann kleine Krümmungen, wo der Mann einen Augenblick wie ein Sclave kriecht. (Das Weib aber[,] das überhaupt in Polen edlerer besserer Natur zu seyn scheint, auch wirklich da regiert) das geht ihren stolzen Gang fort. Nun aber kömmt mit einemmale der Schluß eben so unvorbereitet wie in der Music; mitten in einem Schritt hält der Tänzer ein, und macht einen Bückling bis an die Erde.

nothing but majestic steps, three to a bar. At times there come small bendings over, wherein the man crawls along for a moment like a slave (the woman, however, who on the whole appears to be of a higher, nobler nature in Poland, in fact even governs there); this continues their proud walk. And then all of a sudden, it ends just as unexpectedly as the music; in the middle of a step the dancer stops and does a bow to the floor.Footnote 31

Writing at the Stockholm court in around 1720, Sven Lagergring bemoans the failure of other Europeans to grasp the appropriate style: ‘Polish dances were much in fashion, caused by the many Poles who came. However, there was a big difference between the Poles’ own movements and the Polish dances as translated into Swedish because the Polish women sailed forward like swimming statues, but the fellows, on the other hand, made continuous swingings and noise with their iron heels, which truly looked brisk and light.’Footnote 32

The composers who provided the music for civic events (and much of the instrumental music performed in the city) were members of the royal or aristocratic Dresden Kapellen, such as Johann Baptist Georg Neruda, Johann Georg Knechtel and Johann Adam, or freelance composer-performers, as in the case of Roellig. Numerous sets of Redoutentänze consisting of minuets and polonaises were composed between the 1740s and the 1770s, and many of these were published by the Breitkopf firm. Works that may be connected to the Dresden Redoutensäle with varying degrees of certainty have been listed in Table 1. Other sets of dances possibly intended for Dresden, but not listed in the table, include the orchestral minuets advertised in the Breitkopf catalogues by Johann Erhard Steinmetz and keyboard arrangements of sets of minuets and polonaises by Georg Gebel, (Christian Friedrich?) Horn and Johann Christian Fischer, as well as two sets of polonaises and one set of Styrian dances (steierische Tänze; from the Styria area of Austria) and mazurkas (mazurische Tänze) for two violins and bass by anonymous composers.Footnote 33 A manuscript collection of seven minuets and three polonaises in Marburg by (Johann?) Adam is also very likely to have been intended for Dresden Redouten, though the date is frustratingly left blank in the source: Menuets / et Polonoises / a / Corno Primo. / Corno Secondo. / Flauto Primo et Oboe. / Flauto Secondo et Oboe. / Violino Primo / Violino Secondo. / et Basso. / del / Sig. Adam / Redoute / de l'annee [ . . . ].Footnote 34 Breitkopf also offered sets of dance music by a number of composers associated with cities outside of Saxony, some as far afield as Vienna, attesting to the popularity of the polonaise and its distribution around Europe.Footnote 35

Breitkopf still found it commercially viable to advertise sets of dances from the 1740s and 1750s in its first thematic catalogues of 1761.Footnote 36 However, in later catalogues Breitkopf advertised material that was much more current, as with the Redoutenmusik by ‘Simonetti’ for 1767 and 1768, and occasionally offered music intended for the following season (as in 1768/1769 and 1771/1772). It is clear, therefore, that the firm continued to view such music as a lucrative commercial enterprise. While Roellig, Knechtel and Neruda were fashionable in the 1750s, by the 1760s and 1770s it was to the music of Adam, (Christian Friedrich?) Hennig and ‘Simonetti’ that Dresden danced. Two markets were served by these sets of Redoutentänze: courtly or public events requiring an orchestra to provide an appropriate volume of sound for a large hall, and domestic situations in which music was provided by a solo keyboard. Thus collections by Roellig, Knechtel, Neruda and Adam were offered in both orchestral and keyboard versions. In addition to his polonaises in Redoutenmusik, Roellig composed additional examples of the dance listed in Table 2. The collections in ensemble scorings are also likely to have been destined for the dance hall, but the keyboard set (item 3) and three single keyboard pieces (arrangements of movements from instrumental partitas) are more likely to have been collected by amateur keyboard players.

Table 2 Other sets of polonaises by Johann Christian Roellig

a From a collection of thirty-eight items entitled Clavierbuch | vor | Florentine Tugendreich | Seidelin. | Lauban | 1774. | den 1ten Febr that also includes a minuet and a polonaise from the 1755 collection of Leipzig Redoutenmusik by Knechtel.

The richness of the repertoire for the Dresden Redouten indicates not only a lively interest in new music to support both court and public events, but also a wider market for private performance in the home. That the Breitkopf firm in Leipzig offered many of these dance collections, originally composed by Dresden-based musicians for consumption in that city, indicates the music's broad appeal. It is also likely that music associated with the Redouten acted as a crucible for compositional formulae that Roellig, Gebel, Knechtel, Neruda and others would explore in other genres such as the partita, symphony and homage cantata.

STYLE AND PHRASE STRUCTURE IN ROELLIG'S POLONAISES AND MAZURKAS

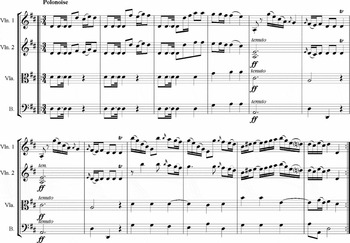

A study of the polonaise within the context of eighteenth-century German music must address the issue of ‘echt’ (authentic) versus ‘unecht’ (inauthentic), complicated by the fact that most surviving examples were not intended as dance music, but rather as characteristic dances or stylized galanteries in suites for keyboard or instrumental ensemble. The distinction between German (‘unecht’) and ‘echt’ polonaises is described in detail in an extended essay published in Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg's Kritische Briefe über die Tonkunst by Christian Friedrich Schale, who claims that many pieces ‘resemble the Polish style only vaguely’.Footnote 37 Daniel Gottlieb Türk highlights the ‘Germanization’ of the genre, but does not identify the features that might be considered authentic: ‘In general, few polonaises written by German composers and danced to in Germany have the character of an authentic polonaise’ (‘Ueberhaupt haben nur wenige Polonoisen, welche von deutschen Komponisten geschrieben und in Deutschland getanzt werden, den Charakter einer ächten Polonoise’).Footnote 38 A similar lack of distinction is found in contemporaneous and modern commentaries. David Schulenberg states that the eighteenth-century keyboard polonaise ‘was a modest dance type whose music originally resembled that of a minuet’, and in Gerber's personal copy of the J. S. Bach's French Suite in E major, bwv817, the polonaise movement is even labelled a ‘Polish minuet’ (minuet polinese [sic]).Footnote 39 These are puzzling remarks when one considers that sets of minuets and polonaises are found in the same collections, and that the dance types have such distinct musical characteristics. Yet they are more understandable if one focuses on the music of J. S. Bach, and in particular on the polonaise in bwv817, where the boldness of the typical Polish rhythms and texture has been dissipated by the even tread of left-hand quavers. Peter Wollny points out that ‘the countless polonaises composed in North and Central Germany during the 1750s and 1760s form a separate tradition that had deviated considerably from the original model’.Footnote 40 This is certainly true of the keyboard polonaises by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, which are sophisticated ‘abstract’ pieces rather than functional dances. In these, phrase structure and modulatory patterns are more akin to those found in minuets than those outlined below. The writing in both hands is often much more florid than in polonaises intended for dancing, as in Example 1. Apart from the stately triple metre and bold rhythmic character, there are few pointers to the polonaise style.

Example 1 Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Polonaise in D major, Fk12/3, bars 1–5, ed. TobisNoten-archiv <www.imslp.org>. Used by permission

A further example of the ornate type of keyboard polonaise composed by musicians in northern Germany is the set of six works published by Friedrich Gottlob Fleischer (1722–1806) in 1769.Footnote 41 This set of dances is preceded by a set of variations, of which the last is also a polonaise. Stereotypical Polish features here include lengthy tonic pedals, typical cadential formulas and rhythmic constructions (discussed below) and a ‘Fine’ indicated at the end of the first repeated section, requiring a dal segno of the first six bars. On top of these characteristic features, Fleischer adds frequent demisemiquaver runs and occasional chromatic scales. Less abstract and stylized than W. F. Bach's Fk12, but nevertheless belonging to the German tradition, are the Johann Gottlieb Goldberg (or Johann Gottfried Ziegler) sets of twenty-four polonaises, each of which is in a different key and explores a different affect.Footnote 42 These generally commence in a simple style, often with hands in octaves capturing the boldness associated with Polish dances, but soon explore more idiomatic keyboard patterns (Example 2). Similar in style are the six polonaises by Bernhard Breitkopf, published in 1769.Footnote 43

Example 2 Johann Gottfried Ziegler, Polonaise No. 6 from 24 Polonoises pour le Clavecin (Berlin, 1764), ed. Maxim Serebrennikov <www.earlymusica.org>. Used by permission

By contrast, the polonaises of composers closely associated with the Brühl Kapelle, which frequently travelled to Warsaw, indicate that Dresden examples of the dance were generally simpler and more ‘orchestral’, and very probably closer to the ‘echt’ polonaise than to the more elaborate ‘Germanized’ one. Much less ornate than some of the examples mentioned above are the keyboard transcriptions of Redoutentänze by Roellig, Neruda and Gebel, which are notable for their simple, bold rhythms and nearly universal two-part texture that render the dances accessible to amateur players (Example 3). In orchestral versions, the two-part texture (with violins mainly in unison) is rendered effective by the instruments’ sustained tone (see Examples 6 and 9 below). Head-motives played in octaves make a bold effect, while the simplicity of the harmonic palette is emphasized by pedal points.

Example 3 Johann Georg Knechtel, Polonaise in D major from Minuets et Polonoises de la Redoute 1755, transcribed from D-Lem, Becker III.8.53

Unlike the minuet, in which phrases are usually constructed in two-bar (six-beat) units that build up into four- and eight-bar periods, the pas de polonaise is a one-bar pattern, allowing for greater flexibility of phrase structure and the creation of five-, six- and ten-bar phrase units.Footnote 44 Frequently, a two-bar cadential phrase will follow a four-bar unit, to create a six-bar phrase. Thus, while on the surface the music will often fall into four-bar phrases, a division into two-bar units tends to predominate. Not unexpectedly, the overall duration of polonaises and disparities in length between the first and second repeating sections tend to be more varied in concert works (final movements of partitas) than in functional dances. To highlight this variety in the following analyses, an upper-case letter denotes a four-bar phrase, a lower-case letter denotes a two-bar phrase and a lower-case letter in brackets indicates a single-bar unit. Thus a six-bar repeated section, a common feature in polonaises and mazurs, might be analysed either as ||: A+b :|| (a four-bar phrase followed by a cadential two-bar phrase), or ||: a+a, b :|| (a four-bar phrase with repetition of the same two-bar melodic unit followed by a cadential two-bar phrase) or ||: abc :|| (three two-bar phrases with contrasting material, the most common pattern in Roellig's dances).

The German polonaise tradition referred to above also left its mark on the dance's tonal plan. In contrast to French and German binary dances in baroque suites, in which there is typically an imperfect cadence or a modulation to a new key at the end of the first repeated section, Dresden polonaises designed for dancing do not modulate.Footnote 45 Instead, the first section remains in the tonic and concludes with a perfect or, less frequently, imperfect cadence. The reason may be seen in the concluding bars of the dance, where there is generally an end rhyme of the final two, four or six bars from the first half. This is most often a verbatim repeat in the tonic, indicated by a dal segno or da capo marking (as in Example 4), and it imposes a severe restriction on the dance's tonal scheme.

Example 4 Johann Christian Roellig, Polonaise from Partita in G major, bars 1–4, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 3228

A lack of surviving indigenous polonaises from the eighteenth century suggests that the dance in popular culture belonged to an oral tradition, making it difficult to know what might constitute its ‘authentic’ characteristics. Limited help is provided by contemporary theorists who highlight several melodic and rhythmic features that ‘define’ the polonaise. As described by Marpurg in 1763, the ‘authentic’ (eigentlich) version always begins on the first beat of the bar, while the German variety may be preceded by an anacrusis and then tends to fall into two-bar phrases.Footnote 46 Indeed, in 1739 Mattheson described the lack of an anacrusis as a particular feature of the dance: ‘The beginning of the polonaise, taken in the strict sense, has something peculiar, in that it begins neither with the half note in upbeat, as the gavotte; nor even with the last quarter of the bar, as a bourrée, but straightaway quite blunt and as the French say, sans façon, commences confidently on the downbeat’ (‘Der Anfang einer Polonoise, in genauem Verstande genommen, hat darin was eigenes, daß sie weder mit dem halben Schlage im Aufheben des Tacts, wie die Gavot; noch auch mit dem letzten Viertel der Zeitmaasse eintritt, wie die Bouree; sondern geradezu ohne allen Umschweif, und wie die Frantzosen sagen, sans façon, mit dem Niederschlage in beiden Arten getrost anhebet’).Footnote 47 This kind of polonaise was the norm in Dresden: an anacrusis is lacking in all of the examples found among the Roellig, Knechtel and Gebel Redoutentänze, and in all but one of the polonaises in Roellig's partitas. Daniel Gottlieb Türk indicates that ‘the polonaise . . . has a solemn and serious character. The movement of true polonaises, of which few fall into two or three parts, is quicker than we usually assume’ (‘Die Polonoise . . . von feyerlich gravitätischem Charakter. Die Bewegung der wahren Polonoisen, worin nur wenige Zwey und Dreyßigtheile [sic] vorkommen, ist geschwinder, als wir sie gewöhnlich nehmen’).Footnote 48 Kirnberger suggests that the basic tempo of the polonaise is somewhere between that of the sarabande and that of the minuet. The more elaborate semiquaver movement in many of the Roellig and Knechtel polonaises would suggest a typical basic tempo of crotchet = 90 for these dances. As was the norm in copies of music for dancing, tempo is never indicated in sources of works by the Dresden composers within this survey. In contrast, the presence of a variety of tempo markings from adagio, through poco adagio, andante, allegretto and molto moderato to allegro moderato is yet another unusual feature of the W. F. Bach polonaises of Fk12, indicating, in the slower tempos, music that is ‘for the ear rather than the foot’. Cramer also comments upon ‘the many syncopated notes, the often free and fast melodic passages, the frequent strong accents that make a really striking contrast with the fast and frequent alternations between forte and piano, and with the unprepared short pauses on the second so-called weak beat of the bar’ (‘die vielen syncopirten Noten, der oft freye und schnelle melodische Gang, die häufigen starken Accente, all’ das macht einen gar auffallenden Contrast mit dem schnell und oft abwechselnden Forte und Piano, und mit dem unvorbereiteten kurzen Schlußfällen auf den zweyten sogenannten schlechten Tacttheil des Tacts’).Footnote 49

Zygmunt Szweykowski suggests that during the eighteenth century, it was the ‘intensive infiltration’ of characteristic rhythms into what had for two centuries been labelled ‘Polish dance’ in Western Europe that defined the ‘polonaise’, a musical term which came to mean the same thing in both Poland and abroad.Footnote 50 He further notes that at the same time as these polonaise rhythms crystallized, the dance's melodic character underwent a change from a predominantly vocal type (prevalent in the seventeenth century) to a type that was essentially instrumental in character, clearly identifiable in Examples 4–6. Several melodic and rhythmic features are typical of the Dresden polonaise:

-

1 An underlying iambic rhythm placing stresses on the second beat

-

2 A rhythmic pattern

,Footnote

51

most commonly set triadically, that later develops into the ‘signature’ rhythm

,Footnote

51

most commonly set triadically, that later develops into the ‘signature’ rhythm

associated with the music of Chopin (see Example 4)

associated with the music of Chopin (see Example 4) -

3 Syncopated patterns set triadically, very commonly employed in opening or middle phrases (see Example 2, bar 1)

-

4 Repetitions of rhythmic cells, particularly in middle phrases

-

5 A cadential phrase of running semiquavers in the penultimate bar leading to the ‘signature’ cadential formula, as described by Marpurg: a melodic resolution in the final bar onto the tonic note featuring four semiquavers leading to a minim or two crotchets, usually ornamented by an appoggiatura (see the final bars of Examples 4 and 5).Footnote 52

Example 5 Roellig, Polonaise from Partita in E flat major, bars 1–6, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 2347

Example 6 Roellig, Polonaise from Partita in D major, bars 1–12, transcribed from D-Bds, SA 2321

The first repeating section in Example 5 features three two-bar units in a typical ‘abc’ pattern, consisting of an opening phrase with a syncopated triadic motive, a central phrase featuring repetition of the ‘signature’ rhythmic pattern, and a cadential phrase featuring the syncopated motive and the most common cadential formula. Other ‘Polish’ characteristics identified by Steven Zohn in the music of Telemann that are also present in Roellig's polonaises include frequent tonic pedal points, reiterative pitches, and unison and octave writing (particularly in the head-motive).Footnote 53 The polonaise from Roellig's Partita in D major (D-Bsa, SA 2321; c1748–1754) provides a striking example of these characteristics (Example 6). Here the strong one-bar motivic repetition in bars 1–3 (presumably based on the one-bar pas de polonaise), frequent unisons, pedal points, simple harmonies, triadic melodic material and sudden dynamic contrasts (implied in bars 5 and 7) all serve to capture the pomp and processional nature of the polonaise. It is the cumulative effect of these musical features that defines the Dresden polonaise style in the period 1740–1760.

FORM IN DRESDEN REDOUTENTÄNZE

Collections of Redoutentänze by Roellig, Knechtel, Neruda, Adam and Gebel may have been performed as continuous sequences, providing a period of uninterrupted dancing to minuets (about twenty minutes) and polonaises (about ten minutes). Such sequences were an important feature of serious and majestic processional dances like the polonaise, which only ended when all the guests had been presented. Unlike the common tonal centre of dances in suites, or the ascending pattern through all twenty-four keys found in the Goldberg (or Ziegler) collections, the sequences of dances in collections of Redoutenmusik underscore the functional nature of the music. Apparently to gain extra length, minuets are often paired into ‘Alternat’ and ‘Trio’ groupings that require a da capo of the first dance, and the sequence of keys indicates that these da capos are integral to the performance of the collection. Similar groupings, though less frequent, can be found in polonaise sequences. Clearly, there was no requirement to end the sequence of dances in the original key. Common to all the surviving Dresden Redoutenmusik by Hiller, Neruda, Gebel, Knechtel and Roellig from the period 1754–1756 is the opening key of D major, no doubt reflecting the scoring of strings with horns. However, the key of the final dance is always closely related to that of the first dance, probably to enable a smooth segue if the sequence were to be repeated.Footnote 54 In the set of parts for 1756 in Schwerin, Roellig's music is interlinked with Knechtel's, suggesting that at least two sets of polonaises and minuets apiece were required for a full evening of music at the Redoute. Footnote 55 Although it is possible that these collections were simply repositories of unrelated single dances that could be combined at will into ‘suites’, the smooth segue of keys between the majority of the items, particularly between the framing movements of the polonaises, strongly suggests a performance in which the players continued for as long as was required, stopping at the end of any particular dance and moving, on cue, to the next required dance. Indeed, the instrumentation of the dances of Roellig's 1756 set of polonaises (for strings, plus pairs of horns and trumpets) tends to support this hypothesis (Table 3). There is no sense of finale in No. 12, which is the only dance in minor mode and is scored for strings only. Horns appear only in Nos 1, 2, and 9, while trumpets are used only in No. 7. Thus the musicians may have played through all twelve dances and then repeated the first seven.

Table 3 Tonalities and brass instruments in the polonaises of Roellig's 1756 Redoutenmusik

In formal terms, Redoutenpolonaisen by Roellig, Knechtel and Gebel employ a restricted number of variants. Most common in the Knechtel and Gebel sets are eight-bar 4:||:4 and, especially, twenty-bar 8:||:12 patterns. The 4:||:4 pattern is favoured in the polonaises of Roellig, who also writes second sections that are considerably longer than first sections (4:||:10, 4:||:12 or 4:||:14), providing relief from the often rigid predictability of musical structures. Only in the longest dances of the 1755 collection by Roellig (8:||:14 and 10:||:14) does he include dal segno structures. Noteworthy is a dance in Knechtel's 1755 collection with an uneven number of bars in the second half (8:||:7).

THE POLONAISE IN ROELLIG'S HOMAGE CANTATAS

Another locus of the polonaise style was instrumental and vocal music written in honour of the electoral throne of Saxony. As noted earlier, Paczkowski has argued that when J. S. Bach wished to allude to the secular power, majesty and might of rulers in works such as the B minor Mass and in occasional music that honoured a representative of the Elector, he sometimes turned to the polonaise or polonaise rhythms to refer directly to the political situation in Dresden. He adds that ‘in the context of Polish-Saxon courtly ceremonies, the polonaise . . . should be understood as a “royal dance”, equally suited to be used as a symbol of royal power in a secular or religious context’.Footnote 56 This also holds true for the four homage cantatas that Roellig composed for the Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum in 1753–1754 to honour the birthdays of members of the Wettin family.Footnote 57 Each cantata is preceded by a symphony that deviates from the normal three-movement plan in replacing the slow and quiet central movement with a stately polonaise or ‘alla Polacca’. The symphonies of three of the four homage cantatas also exist separately as concert works (Table 4).Footnote 58 For these three works, dedicated to minor members of the royal family, the inclusion of horns may allude to hunting, a favourite royal pastime. Of all possible topoi in the mid-eighteenth century, ‘perhaps none held as deep resonance for Dresden as the hunt, which accompanied many of the social and political activities involving the Elector of Saxony’.Footnote 59

Table 4 Polonaise movements in Roellig's symphonies

Roellig was not unique in including polonaise and alla polacca movements in symphonies dedicated to the Saxon royal family. Gottlob Harrer (1703–1755), Kapellmeister to Count von Brühl, included an alla polacca as the central movement of his Sinfonia in D major (1747) and a polonaise as the final of nine movements in the Sinfonia in G major (1737).Footnote 60 Both symphonies were performed for the royal party at the hunting lodge at Hubertusburg following a vigorous day in the saddle, and are scored for three horns, woodwind and strings, featuring movements in compound time imbued with hunting calls in the horns.Footnote 61 Stanilaus Poniatowski describes a typical day of hunting and lavish entertainment at Hubertusburg starting with an opulent breakfast served from the king's carriages on the hunting grounds. The hunt would then move into the forest, followed by courtiers and staff in livery and by twenty-four carriages, some carrying ladies of the court. Following a lunch, served again from carriages, the hunt would continue into the afternoon. After some free time to freshen up and change clothes, activities moved to the theatre, where there was hunt music (‘Jagdmusik aufspielte’) and an opera.Footnote 62 An example of the latter is Hasse's La Didone abbandonata, performed at Hubertusburg in 1742, in which the sinfonia's central movement is an alla polacca scored for strings and a pair of horns.Footnote 63 The musical entertainment was then followed by dinner at the king's table and finally conversation in private chambers. As Poniatowski notes, the hunt concluded not with the killing of the deer, but only following the entertainment and evening meal.

Compared with his Redoutentänze, Roellig's symphony polonaises adopt more stylized formal structures, such as rhyming two-phrase micro-structures or rondo-like structures. In these works, rhyming is created not only by the use of the same melodic material in the closing bars of each repeated section (often a verbatim repetition of the first repeated section's concluding phrase through a dal segno indication), but also by a three-phase periodic repetition of material throughout the movement. In its simplest form, as found in the Symphony in C major (D-Bsa, SA 2300), this repetition involves two phrases that are repeated with harmonic variation: ||: AB :||: A1B, A2B :||. Repetition is also a feature of the micro-structure: common to both the ‘A’ and ‘B’ phrases is the recurrence of the initial one-bar motive in each phrase (Example 7).

Example 7 Roellig, Polonaise from Symphony in C major, violin 1 part, transcribed from D-Bds, SA 2300

A variant of the two-phrase structure occurs when new material is introduced at the beginning of the second repeated section, as seen in the Symphony in D major (D-Bsa, SA 2301). Here the second section echoes the first through returns of ‘B’ material: ||: A+B :||: C+B1, A1+B :||. In the polonaise movement of his Symphony in B flat major (D-Bsa, SA 3213) Roellig goes one step further by establishing a rhyming two-phrase structure that creates a rondo–binary hybrid form: ||: AB :||: CB, DB :||. A similar structure can be seen in the six-bar phrases (bb, c) of the polonaise in the Symphony in B flat major (D-Bds, SA 3206), where new material (‘D’ and ‘E’) is heard in place of ‘A’ during the dance's second half (Example 8):Footnote 64

Example 8 Roellig, Polonaise from Symphony in B flat major, violin 1 part, transcribed from D-Bds, SA 3206

Bars 11–14 (‘D’) display a feature common to many polonaises: a sequential phrase consisting of three statements of a one-bar pattern, concluding with a cadential bar. The effect of this strophic micro-structure, and of the dal segno, is not only a restricted harmonic scheme, but also a breaking-down of the binary structure that is so prevalent in dances of the baroque suite.

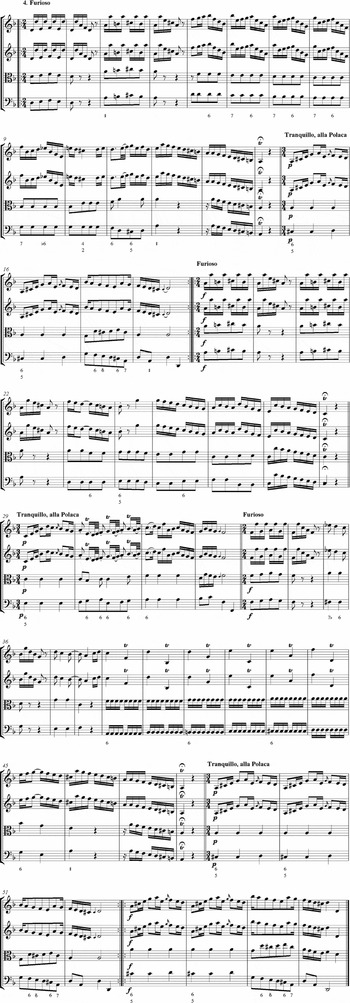

POLONAISE MOVEMENTS IN DRESDEN PARTITAS

The Dresden partita was cultivated principally in the 1740s and 1750s by composers who lived and worked in the Dresden area.Footnote 65 Their remarkably consistent use of the minuet and polonaise as final movements elevated the latter dance from an occasional movement in contemporary suites to a pivotal feature of the partita; very few of Roellig's partitas do not conclude with a polonaise or an alla polacca movement. Apart from one partita in six movements and a few more in three, Roellig's partitas fall into two main groups: those with four movements (the majority) and those with five. All movements, except for the occasional introductory adagio, are in some type of binary form, with some opening movements in sonata form. Most partitas conclude with a single binary polonaise ranging from eight to thirty-two bars in length. But there are also polonaises with trio sections or sets of variations, polonaises alternating with contrasting dances such as the musette and mazur, and movements featuring contrasting Furioso and Tranquillo, alla Polaca sections. Roellig cultivated each of these movement types during specific periods: polonaises with trios were composed only up to c1752, variation movements only appear in a cluster of works from 1756 to 1760, and the movements contrasting Furioso and Tranquillo, alla Polaca sections conclude three partitas (which also exist in arrangements for flute or violin with keyboard entitled divertimento) composed c1758.Footnote 66 In these last movements, Roellig adopted a novel approach to form: within an overall binary structure that includes a coda, they alternate four-bar Tranquillo, alla Polaca sections with Furioso sections varying in length and material. Note in Example 9 that each Furioso section ends with an imperfect cadence and fermata (bars 14, 28 and 48). In keeping with the polonaise structures discussed above, the rhyming four-bar Tranquillo, alla Polaca sections that conclude each of the two binary halves (bars 15–18 and bars 49–52) provide identical endings in the tonic. The medial Tranquillo, alla Polaca in the second repeating section (bars 29–32) is varied and in the relative major, whereas the coda (bars 53–56) reproduces the tonic statements an octave higher.Footnote 67

Example 9 Roellig, Finale of Partita in D minor, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 2318

There are echoes in the striking juxtapositions between the quiet Tranquillo, alla Polaca sections and loud, energetic Furioso sections of ‘die lustige polnische Ernsthaftigkeit’ (the comic Polish seriousness) identified by Telemann.Footnote 68 This characterization is expanded upon by Johann Adolph Scheibe, who remarks that the Polish style ‘is quite comic, but nevertheless of great seriousness. One may very easily employ it for satirical purposes. It seems to almost mock itself: in particular it befits a really serious and bitter satire’ (‘Insgemein ist diese Schreibart zwar lustig, dennoch aber von großer Ernsthaftigkeit. Man kann sich auch derselben zu satyrischen Sachen sehr bequem bedienen. Sie scheint fast von sich selbst zu spotten: insonderheit wird sie sich zu einer recht ernsthaften und bittern Satire schicken’).Footnote 69 While Roellig might not have been seeking to engender a comic effect in his music, it is not difficult to hear echoes of the comic–serious dichotomy echoed in his furious–tranquil alternations. More significant, in any case, is the association of tranquillity with the alla polacca style, implying an inherent stateliness to the polonaise.

FORM IN PARTITA POLONAISES

The proportional length of the two halves in Roellig's partita polonaises demonstrates the variety of structure among his sixty-four examples of the dance. While there is greater variety in the partitas than the Redoutentänze, the proportions 4:||:4 (twelve examples) and 8:||:12 (nine examples) are the most common in both genres.Footnote 70 Of particular interest are partita polonaises with odd numbers of bars in one or both halves (5:||:8, 5:||:13 and 6:||:11), and one with a shorter second half (8:||:6).Footnote 71 These asymmetrical structures suggest that the music is for the ear rather than for the foot. Usual in this repertory is a first repeated section ending with a perfect cadence in the tonic key and a second repeated section that is longer than the first (only one polonaise has a first section longer than the second). Most dances feature some kind of rhyming of the final bars in each half, but, as Table 5 shows, the amount and nature of repeated material varies. Of the fifty partita polonaises longer than ten bars, no two have an identical structure. But shorter movements are more uniform: all but one of the eight-bar dances have an ab:||:cd form, while the ten-bar (4+6) examples have an ab:||:ccb form. All but one of the dozen eight-bar polonaises in the partitas have a non-rhyming ||: ab :||: cd :|| structure, and these fall into two chronological subgroups (c1748–1754 and c1756–1757).Footnote 72 Seven dances in the later subgroup include a set of three variations followed by a da capo of the polonaise, the only use of variation technique in Roellig's entire oeuvre.Footnote 73 Variations either follow a passacaglia model, in which the bass line (a viola bassetto) is more or less intact during each variation (SA 2342 and 3233), or adopt a concertato texture in which violin 1, violin 2 and cello are assigned solos in successive variations (SA 2352, 2355/2366 and 2356/1).

Table 5 Rhyming in Roellig's partita polonaises

Thematic materials can be very restricted: in some examples no new material is presented in the second repeating section, such the movement in the Suite in B flat major, which has the structure ||: ab :||: a1a1| b1b :||.Footnote 74 Many four-bar phrases consists of a one-bar pattern stated three times, often sequentially, followed by a cadential bar, as in the second polonaise of the Partita in B flat major (D-Bsa, SA 2410). In this instance, no new material is presented in the second half of the dance: ||: Abc :||: Abc1, b1c2, bc :|| (Example 10).Footnote 75 In the second polonaise Roellig appears to be exploring a different Polish dance style, as there is no syncopation and the initial rhythmic repetition (bars 1–4) and following motive (bars 5–6) are characteristic of the mazur.

Example 10 Roellig, Polonaise 2 from Partita in B flat major, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 2410

Among dances with five-bar units, the first polonaise of the Partita in B flat major (D-Bsa, SA 2410) includes an ‘extra’ bar between the sequential music of bars 7–10 and the reprise of first-half music in bars 12–17, creating the structure ||: abc :||: dd(e) | abc :|| (Example 11). Featuring a dotted rhythm derived from ‘c’, bar 11 provides a link back to the head-motive. In two examples, the single bar is the opening bar (head-motive) of the dance. The five-bar section of the polonaise from the Partita in A major (SA 2392 / SA 3224) is constructed from a single bar (‘a’) followed by a two-bar unit (‘b’) and a two-bar cadential phrase (‘c’), the last two segments restated verbatim at the end of the second section: ||: (a)bc :||: dd | bc :|| (Example 12). A similar 1+2+2 structure can be perceived in the Partita in C major (SA 2394), which is divided ||:5:||:13:||. A da capo repetition of the first half creates an overall structure of ||: (a)bc :|| de ff | (a)bc || (Example 13).

Example 11 Roellig, Polonaise 1 from Partita in B flat major, bars 7–17, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 2410

Example 12 Roellig, Polonaise from Partita in A major, bars 1–5, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 2392/3224

Example 13 Roellig, Polonaise from Partita in C major, transcribed from D-Bsa, SA 2394

Some of the lengthier polonaises have a more complicated internal organization, such as the rondo-like dance in the Partita in C minor (D-Bsa, 2421), which divides into three ten-bar units: ||: ab, ccd :||: ab1, ccd | E, ccd :||. Similarly, in a thirty-bar dance in the Partita in C major (SA 2413/3229), the last four bars of the first half return to punctuate two sets of new material in the second half: ||: aa1, bb 1, cd :||: b2e, cd1 | gg, cd :||.

POLONAISE AND TRIO, MUSETTE AND MAZUR

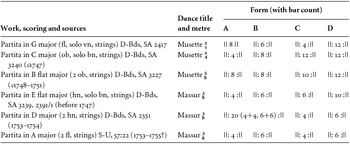

In several of Roellig's partitas from the period c1747–1752 there are instances in which a polonaise is followed by another movement acting as a trio, requiring a da capo repetition of the polonaise.Footnote 76 Only in three movements is the second dance another polonaise.Footnote 77 Elsewhere, the second dance is another rustic type featuring drones. Of the three entitled ‘musette’, two are in duple time and another in triple time is a mazur in all but name. In three other movements, the second dance is labelled ‘massur’. Common to all movements with musettes or mazurs, which are listed in Table 6, is a scoring for two obbligato instruments in addition to strings.

Table 6 Musette and mazur movements in Roellig's partitas

Roellig's mazurs, which he normally identifies as such, are among the earliest instances of the dance in mid-eighteenth-century German concert music. No other examples dating from before c1770 appear in RISM, while the first to be advertised by Breitkopf are those by Simonetti for the 1768 Dresden Redouten (see Table 1). There is little indication of how the mazur was danced, but it appears to have been introduced into German courts by Friedrich Augustus II (1697–1733), who was fond of it.Footnote 78 In any case, the dance was known to mid-eighteenth-century German musicians, since Joseph Riepel (who lived in Dresden from 1739 to 1745) mentions the term ‘massur’ in 1752.Footnote 79

For both the musettes and mazur, Roellig adopts a four-part double-binary form, a structure associated with the ethnic mazur.Footnote 80 In the D major mazur (Bds, SA 2351), the repeats in the A and B sections are written out and the whole A+B complex is repeated. The G major musette (SA 2417) shares its 8+6 structure with the example of a mazur given by Marpurg, while the 4+4, 6+6 structure of the A and B sections is common to all three mazurs listed in Table 6.Footnote 81 All three examples of the dance lack the irregular accents on the second and third beats of the bar that are a typical feature of this type, but they include drones that allude to the dudy, a rustic bagpipe associated with the performance of mazurs in Poland. They also feature the aabb and aaab phrase structures associated with the folk dance.Footnote 82

As is typical in rustic mazurs, Roellig repeats the rhythmic motive in the first four bars of the A major mazur, while the motive in bar 21 dominates the second half of the dance. Rustic features in this dance include strong second beats (bars 1–4, 6 and 9), lively dotted rhythms, and persistent tonic and dominant pedals evoking the drones of the dudy. In contrast to the musettes described above, the form includes no rhyming and has a simple melodic construction based on mainly two-bar units: ||: A :||: bb, c :|| ||: dd :||: dd, e :|| ( Example 14). The B flat major ‘musette’ is essentially a mazur and shares features with the D major dance, most notably a tonic pedal for the duration of the first two repeated sections and a metrical shift effected by displacing the initial anacrusis to the downbeat in subsequent phrases, a further characteristic of the dance (Example 15). Similar alternations of phrases with and without an anacrusis continue in the second half of SA 3227, where there are phrases with and without an anacrusis in a ||: dEF :||: GEF :|| rhyming structure supported by alternating tonic and dominant harmonies (Example 16).

Example 14 Roellig, ‘Massur’ from Partita in A major, bars 11–30, transcribed from S-U, 57:22

Example 15 Roellig, ‘Massur’ from Partita in B flat major, bars 1–8, transcribed from B-Bsa, SA 3227

Example 16 Roellig, ‘Massur’ from Partita in B flat major, bars 17–38, transcribed from B-Bsa, SA 3227

Just as the minuet became established as an essential movement type in late eighteenth-century Viennese string quartets and symphonies, the polonaise found a home as the final movement of the Dresden partita. Ultimately, however, it failed to survive the end of the Seven Years War and the political changes following the deaths of Count von Brühl and Augustus III in 1763. The few post-1763 Dresden partitas including polonaises are mostly the work of composers based in Leipzig, such as Johann Gottlieb Wiedner, Georg Simon Löhlein and Christian Gottlob Neefe. Although it is not easy to gauge how ‘Germanized’ the polonaise became during the eighteenth century, a clear division is apparent between stylized examples and the more simply constructed examples found in the Dresden dance repertory. If there was an understandable tendency to add ‘order’ to rustic dances in the process of making them palatable to courtly tastes, then the Dresden repertory is at least mostly free of the lampooning or satirical quality observed in polonaises by some eighteenth-century commentators.Footnote 83 Many Dresden musicians enjoyed first-hand knowledge of the Polish style as a result of their regular visits to Warsaw, and they appear to have preserved something of the folk roots of the polonaise and mazur though bold melodic material, strong rhythms, textural clarity and varied formal plans.

As this study has shown, functional dances produced for the Redouten display less formal variety than dances in concert works such as partitas and symphonies, where one finds more complex phrase structures and rondo-like or through-composed forms. In some later partitas and divertimenti by Roellig, the polonaise is subject to abstraction and modification through the application of variation technique and alternations of Tranquillo, alla Polaca and Furioso sections. The sheer quantity of dances produced by Roellig, together with the formal variety outlined above, provides not only valuable insights into the style and construction of polonaises and mazurs in Dresden, but also useful a reference point for studying examples by other eighteenth-century composers.