Two hundred and fifty years ago, on 3 January 1766, Peter Ludwig Rahier, Prince Nicolaus Esterházy's estates director, informed the administrators of the Esterházy tenures throughout Hungary that the ‘castle near Süttör’ had been renamed ‘Eszterház near Süttör’ by the prince. Thereby the name Eszterháza became official.Footnote 1

I first visited Eszterháza – or, as it was consistently referred to at the time, the Esterházy palace of Fertőd – in the late spring of 1964 on a school trip. I clearly remember the guide referring to the hall adjacent to the first-floor ceremonial hall on the inner courtyard side, approachable both via the staircase inside the building and via the external ceremonial staircase and terrace, as the ‘music hall’ (Figure 1); this sounded peculiar because everyone knew and considered it natural that the venue for the palace concerts would have been the splendid ceremonial hall itself (Figure 2). In fact, in recent times the ‘music hall’ has been officially referred to as ‘the Haydn hall’. Eszterháza has undergone numerous changes since my school trip; however, on my most recent guided tour, in 2013, the guide not only described this hall in the same way but was even more explicit: ‘this is the hall where Joseph Haydn and his musicians made music’.

Figure 1 Photograph of first-floor dining hall, c1940, taken by Károly Diebold. The doors of the ceremonial hall are situated behind the photographer. Soproni Múzeum (Sopron Museum). Used by permission

Figure 2 Photograph of ceremonial hall, 1935, taken by Károly Diebold. The glass door to the left of the corner opens into the dining hall. Soproni Múzeum. Used by permission

Trouble is, there is no reference to the hall as a music hall in the eighteenth century, either in the extensive archives or in contemporary descriptions. As we shall demonstrate, during the lifetime of Prince Nicolaus Esterházy I (‘The Magnificent’; 1714–1790) and Haydn, the hall was chiefly used for dining. In the well-known illustrated description of the palace and the Eszterháza estate, Beschreibung des Hochfürstlichen Schlosses Esterháß im Königreiche Ungern, published in Preßburg, the ceremonial hall is referred to as ‘Paradesaal’ and the adjacent hall simply as ‘Vorsaal’ (entrance hall, antechamber).Footnote 2 Gottfried von Rotenstein, author of the most thorough account,Footnote 3 also calls them ‘Paradesaal’ and ‘Vorsaal’ in both the 1783 and 1793 editions of his book; both texts use the adjective ‘prächtig’ (splendid).Footnote 4 However, in his travel book of 1782 Heinrich Sander labels them as ‘Gesellschaftssaal’ (social or party hall) and ‘Speisesaal’ (dining hall) respectively.Footnote 5 Johann Matthias Korabinsky, editor of the Preßburger Zeitung, refers only to ‘großer Saal’ (great hall) in his almanac of 1778, but in his 1786 lexicon of Hungary names both halls, calling the ceremonial hall ‘Prachtsaal’ (state hall) and the adjacent space, similarly to Sander but apparently independently of him, ‘Speisesaal’.Footnote 6 The internal financial documentsFootnote 7 and the great palace inventory of 1832Footnote 8 call the ceremonial hall simply ‘Grosser Saal’ (big hall) and the other one ‘Vorsaal’ or ‘Oberer [upper] Vorsaal’ to distinguish it from the hall directly below it that gives on to the ceremonial courtyard; in a list of the palace rooms it is plain ‘Vorzimmer’ (anteroom). Three well-known French accounts only mention the ceremonial hall – as ‘grand sal(l)on’, and, occasionally, as ‘salon d'enhaut’ or ‘salon du haut’ – to differentiate it from the hall on the ground floor.Footnote 9

Since some of the contemporary descriptions take the ground floor as their point of reference, and because we have begun referring to palace documents, it would seem useful to consider the names given to the two large ground-floor spaces as well. As we shall see, the functions of the two floors are inseparable; hence we will be able to survey the entire corps de logis of the palace.

The ground-floor hall with its arches (Figure 3), opening onto the parterre and overlooking Lés wood, is called ‘Sala Terrena’ in the German descriptions, in several versions of Italian and French spelling; the Beschreibung also calls it ‘Unterer [lower] Saal’.Footnote 10 The names used for the adjacent room (Figure 4), overlooking the ceremonial courtyard, just like those of the smaller hall above, include references to function: what Rotenstein labels simply as ‘Vorsaal’, the Beschreibung, the most ‘authoritative’ source, denotes, somewhat awkwardly, ‘Vor- und Sommerspeisesaal’ (entrance and summer dining hall). Sander does not write about the ground floor; in 1778 Korabinsky mentions the ‘Sala Terena’ only, but in 1786 the ‘Vorsaal’ as well.Footnote 11

Figure 3 Photograph of Sala Terrena, c1894, taken by an unknown photographer. Behind the glass door is the summer dining room. Iparművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Applied Arts), Budapest. After a reproduction published in Művészi Ipar 9 (1894), 159

Figure 4 Photograph of the summer dining room in 2015, taken by János Mácsai. Behind the glass door is the Sala Terrena. The puppets on show have no historic relevance. Used by permission

In the estate-management documents the ground-floor spaces are always called ‘Sala Terrena’ and ‘Vorsaal (zur Sala Terrena)’ respectively. Of the three French accounts, Excursion à Esterhaz en Hongrie en mai 1784 does not discuss the ground floor; the Relation des fêtes données à sa Majesté l'Imperatrice par S. A. Mgr le Prince d'Esterhazy dans son Château d'Esterhaz le 1r & 2e 7bre 1773 and the memoirs of Zorn de Bulach are unaware of the Sala Terrena label: they call it ‘salon d'enbas’ (lower hall) and ‘salon du rez-de-chaussée’ (ground-floor hall) respectively, without mentioning the antechamber, similarly to their descriptions of the first floor.Footnote 12

The survey above does not encompass all contemporary sources known to me, but any reference to a ‘music room’ or similar is absent in all the other sources as well. Figure 5 is a floor plan showing all namings of the four spaces in question quoted above.

Figure 5 A schematic floor plan of the four large spaces of the corps de logis of Eszterháza Palace, showing their various names as found in contemporary sources. The bigger room on the first floor is the ceremonial hall. Drawing by architect Gergely Patak

The matter gets more complex, however, if we take into account the contemporary references to music-making. In respect of the four big central halls we have two specific references to venue from Nicolaus the Magnificent's time. The earlier one is found in Relation, revealing that on the occasion of Maria Theresia's famous visit in 1773 the serving of grand meals alternated between the ground floor and first floor ‘salon(s)’ – that is, assuming the description is accurate, not their antechambers, even though the primary function of these latter spaces was as dining halls. What is more, on the second day of the sovereign's visit, in the course of the first lunch, served on the first floor for thirty-five covers, some kind of mealtime music-makingFootnote 13 is said to have taken place: ‘Pendant le diner, plusieurs musiciens du Prince, chacun excellent dans son genre, ont eu l'honneur d’être entendus de S. M. I. & d'en mériter des applaudissemens’ (During lunchFootnote 14 a few of the prince's musicians, each excellent in his own field, had the honour of being listened to and rewarded with applause by Her Imperial Majesty).Footnote 15 This event was also recorded, considerably later, by Rotenstein in 1793, but he did not specify the venue; according to him, the ‘herrliches musikalisches Conzert’ (superb musical concert) included a solo played on a ‘Pandorino’ (probably pandurina or mandolin).Footnote 16 It is difficult, if not impossible, to establish from this description where precisely the musicians were placed; my acoustic experience of the venue suggests it is unlikely that the musicians would have been playing in the antechamber for the diners in the ceremonial hall. What is without doubt is that this contemporary description, uniquely, draws a connection between the entrance/dining hall, referred to these days as ‘music hall’, and music-making.

The other piece of information relating to music-making in the central part of the palace originates from Rotenstein and appears in slightly differing versions in the 1783 and 1793 editions of his book. In 1783 Rotenstein concludes his description of the Sala Terrena with an abrupt switch to its anteroom: ‘Im Vorsaal ist alsdann Musik von 36 Musicis: so stark is die Kapelle des Fürsten’ (In the antechamber thirty-six musicians play: this is how large the prince's orchestra is).Footnote 17 In the 1793 version Rotenstein moves from Sala Terrena to antechamber in mid-sentence: ‘Hier [in the Sala Terrena] wird im Sommer gespieltFootnote 18 und im Vorsaale eine Musik von 36 fürstlichen Tonkünstlern unterhalten’ (This is where they play in summer and in the anteroom thirty-six princely musicians provide music).Footnote 19 Being originally familiar with the earlier version only, I started suspecting the veracity of this description a long time ago, because the anteroom (Figure 4) that looks out onto the ceremonial courtyard would have provided an extremely confined space for thirty-six musicians, no matter how ‘period’ their instruments were, not so much because of its limited floor space as its low ceiling; not to mention the fact that the number of musicians in the ‘Kapelle’ – officially named ‘Cammer-Music’ – not counting the singers, never exceeded twenty-four. On the occasion of the visit to KittseeFootnote 20 by Maria Theresia and Joseph II in July 1770, effectively a dress rehearsal for the later Eszterháza festivities, Rotenstein tells us that a thirty-six-member ‘Musikchor’, ranged on the staircase, awaited the dignitaries.Footnote 21 Yet a bill referring to the same occasion confirms that at the time the Cammer-Music only had sixteen instrumentalists.Footnote 22 If we further consider the fact that at a 1763 ball in Eisenstadt twenty-four ‘Ballgeiger’ (ball fiddlers) were paid,Footnote 23 even though the prince's own ensemble consisted of precisely half that number at the time,Footnote 24 the picture that emerges is that for occasional entertainment purposes – ‘unterhalten’ as Rotenstein calls it – the ensemble was regularly enlarged to two or three dozen by employing extra musicians. If these musicians only played mealtime entertainment and dance music, then the acoustic expectations would not have been highly sophisticated. Besides, the adverb ‘im Sommer’ of the second version could well refer to the music-making as well as to dining, further strengthening the ad hoc character of the thirty-six-strong ensemble. (There is mention of the thirty-six musicians in the summer dining room in Korabinsky's 1786 text as well.Footnote 25 )

Yet more considerations arise from the fact that in contemporary accounts another, less central, area of the palace is mentioned as a concert venue. One source is the traveller Sander. He does not refer to music at all in relation to the central spaces, but when listing Eszterháza's twenty-six most notable attractions, in second place he says this: ‘Ein Sommermusiksaal ganz mit Gemälden behangen, unter welchen besonders zwei sehr rar und schön seyn sollen; – schöne Aussichten auf den Neusiedler See hinaus hat man hier auch’ (A summer music hall full of paintings, two of which are supposed to be particularly rare and beautiful; from here there is also a good view of the NeusiedlerseeFootnote 26 ).Footnote 27 A hall full of paintings and with a view of the lake can only be the picture gallery, which protrudes at length from the western wing; from the central section of the palace, naturally with the exception of the belvedere, there is no view of the lake at all, since its windows either face south, the opposite direction to the lake, or else open onto the ceremonial courtyard. The winter garden affords some view in a north to north-westerly direction, but it definitely did not house a multiplicity of paintings (refer to Figure 6).

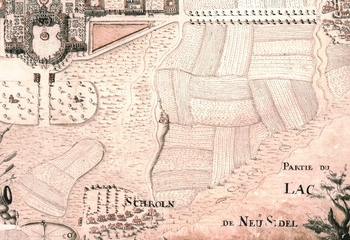

Figure 6 Detail of the ‘Sienna plan’ of Eszterháza by Nicolas Jacoby, c1768–1772. Some buildings shown here were actually finished later. On the plan west is to the right and south is upward, and so the Neusiedlersee is to be found in the lower right-hand corner. The figure shows clearly that the northern windows of the picture gallery (the right-side horizontal protrusion of the palace) offer the best view onto the lake (except for the rooms in the arched wing closest to the gallery, housing the library). MTA BTK Művészettörténeti Kutatóintézetének Fotótára (Photo Collection of the Institute of Art History of the Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences). Used by permission

Thus, relatively far from the central part of the palace an authentic, though seasonal, music venue has been found, even if only mentioned in passing by one visitor. This piece of information from 1782 corresponds with the following assertion by H. C. Robbins Landon: ‘On 30 May [1781], during one of the visits of Duke Albert of Sachsen-Teschen and his wife, Archduchess Marie Christine, to Eszterháza, there was an extraordinary concert held in, of all places, the picture gallery.’Footnote 28 Unfortunately, Landon does not offer a reference. Of the newspapers that might normally have provided such information, the 30 May issue of the Preßburger Zeitung only mentions the plan of the ducal couple's visit to Eszterháza;Footnote 29 the Wiener Zeitung of 2 June, however, informs us that the couple had travelled from Vienna to Preßburg on 26 May and, having stopped there overnight, travelled on to Altenburg (today's Mosonmagyaróvár), arriving back in Vienna on 30 May.Footnote 30 These details put a possible Eszterháza visit somewhere around 28 to 30 May, confirmed by the information, again without reference, available in the itinerary of the prince,Footnote 31 according to which the Sachsen-Teschens spent 29 and 30 May 1781 at Eszterháza. Although the source of the information relating to the musical occasion remains unclear, the agreement between the data makes it likely that Landon drew on a reliable source. Finally, Az eszter-házi vígasságok (The Merriments of Eszterháza), a famous poem by György Bessenyei that was published in 1772, reserves its most lyrical passages for the description of music-making, although the poem says nothing about the venue or any detail about the music played.Footnote 32

In summary, the accounts mention three parts of the central building as musical venues of some kind: the ceremonial hall (or its anteroom) on the single occasion of Maria Theresia's 1773 visit; the antechamber to the Sala Terrena or the summer dining room, as a general venue for summer music; and the picture gallery as another summer music venue, but also the venue for a specific concert at the end of May 1781 – almost a summer date.

All this leads us to conclude that if one of the fundamental function(s) of the ceremonial hall, or its antechamber, had been the hosting of musical performances, this might have been reflected in the names by which the rooms were known. However, there are no such indications.

The only kind of music-making discussed thus far has involved occasional programmes: the entertainment of high-ranking visitors, mealtime music and summer music – possibly outdoor in nature. Could these have been the accademies for which Haydn composed his symphonies and concertos, aiming to satisfy Prince Nicolaus's sophisticated tastes? This is hardly likely: it should suffice to remind ourselves of the mandolin solo performed at Maria Theresia's lunch, with the mandolin being associated with lighter musical styles. Where, then, did the real accademies take place?Footnote 33

Landon offers a ready answer: in the ceremonial hall. His ‘evidence’ is based on his way with words: he ‘translates’ the German names of the ceremonial hall he quotes without hesitation as ‘concert-room’Footnote 34 and thus appears to solve, or render non-existent, the problem of the venue. In contrast with Landon and with the general consensus, Georg Feder wrote in 2002:

Haydn's concerts (with his orchestra or with a smaller ensemble), despite today's opinion, probably rarely took place in the ceremonial room on the first floor of the palace. Rather, according to witness reports, in the Sala Terrena on the ground floor, in the picture gallery, where on the afternoon of 30 May 1781 a concert took place in the presence of Duke Albert of Sachsen-Teschen and his spouse, Archduchess Christine, in the opera house and, according to a register from the year 1778 (C. F. Pohl 1882, pages 367ff., see Lit. G.), in the apartment of the prince (Academia musica nell’ Appartamento).Footnote 35

The goal of this article is partly to substantiate Feder's statement (which refers to just one document), and partly to refine it on the basis of more archival sources. (In fact, the only major correction I can add to his statements is the replacement of the Sala Terrena by its anteroom.)

As far as Landon is concerned, he, too, ought to have been aware that the situation was far from that simple, since he was forced to acknowledge the problem when discussing the overall programme of the 1778 season by Philipp Georg Bader, also mentioned by Feder. (Bader, princely librarian since 1774 or 1775, assumed the directorship of the opera house and marionette theatre once founding director Carl von Pauerspach left after the 1777 season.) The complete title of this document is ‘Verzeichniß der Opern, Academien, Marionetten und Schauspiele welche von 23n. Januarii bis Xbris 1778. auf den Hochfürstliche [sic] Bühnen in Esterhatz gegeben worden sind’ (List of Operas, Academien, Puppet Shows and Plays Performed from 23 January until December 1778 at the Princely Theatres of Eszterháza).Footnote 36 This annual list of events includes six concerts, even providing a rough programme for two of them. In connection with the first orchestral ‘Academie’ Landon writes: ‘Jan. 30: “Academie” (concert), held in the great hall, one presumes’.Footnote 37 This facile ‘one presumes’ has, however, a rickety foundation: if the consistently meticulous Bader mentions that three of these ‘Academia musica’ occasions – most probably chamber-music recitals – took place in the prince's private quarters (that is, at a venue that is different from those listed in the document's title), it is most likely that he would have also indicated a specific venue for the two orchestral ‘Academies’ if they had been given somewhere other than the theatre; not to mention the question that if the theatres did not host concerts of any kind, what possible reason could there be for the accademies to appear on the title page of the document?Footnote 38

Is it possible that the explanation resides in the somewhat fussy title of Bader's list? I think the answer is yes, all the more so because this is not an isolated piece of evidence: it is supported by several other available documents from which, hitherto, no one has drawn the readiest conclusions.

The 1778 theatre-management regulation, quoted by several scholars and published in its entirety both in Mátyás Horányi's The Magnificence of Eszterháza and later by Landon,Footnote 39 reads: ‘9no: Wird eine Stunde nach jeder Oper, Comedie, und Akademie gleichfahls zur Vorbeügung aller Gefahr, der Wache habende Corporal der Grenadier Zimmerman, und ein Trabanth das Theater visitiren, worüber Unser Unter Lieutenant den Befehl erhalten wird’ (9. One hour after each opera, play or concert [Akademie], the corporal on duty together with Grenadier Zimmermann and a guardsman will inspect the theatre premises, with a view to preventing all possible dangers. Our Sub-Lieutenant will receive the appropriate instructions).Footnote 40 This document proves beyond doubt that ‘Akademien’, too, took place in the (first) opera building: the text explicitly discusses the security arrangements following theatrical performances, and the mention here of ‘Akademie’ would make no sense if the venue for the concerts had been a different part of the palace.

However, an objection could be raised along the following lines: since these instructions pertain to the concerts put on in the theatre only, the possibility of part, or even the majority, of concerts being performed elsewhere cannot be ruled out. This objection can be dealt with by referring to another, not altogether unfamiliar but less well-known document (Figure 7).Footnote 41 The facsimile shows the third page of a three-page document whose first page contains the following heading: ‘Zimmer Tag Werk in Verrichtung des Hochfürst. schloß Esterhas dan andern nothwentigen Reparation in Monath Marty 776’ (Carpentry day-rates completed in the Eszterháza princely palace and other necessary repairs in the month of March 1776). Such documents were created throughout the year at fortnightly intervals; in the theatrical season the overtime (‘Extra Stunden’) that the carpenters had completed in the theatre was accounted for in this manner. The third page of the document gives details of precisely such work, including the description of the types of events taking place there day by day; this is the kind of detail, sadly, not recorded either before or after this period in this type of document. Below we give the transcription of the page:

Extra stunden in denen Cometihäusern

N: Bey denen accademien hat kein zimmerman Etwas zu Thun in Theatro, mithin sollen auch keine stunden Eingerechnet werden, sondern der Pollier oder Ein ander zimmerman wird künftig vor der Music die luster anzünden, vor 8 uhr sodan die lampen in der Allée, und nach der Music außlöschen.

Anton Kühnel MP

Bausch.Footnote 42

Figure 7 An account for carpentry work completed in the palace between 11 and 23 March 1776. Esterházy Privatstiftung Archiv, BC 1776, Bau Cassa Rechnungen N 16. Used by permission

(The notes that follow the list translate as follows: ‘NB: With respect to the accademies none of the carpenters have any jobs in the theatre, therefore overtime cannot be charged, but henceforth the foreman or another carpenter will light the candelabra before the beginning of the music, and before 8 o'clock also the lamps in the alley, and after the music he puts them out.’)

This account points a narrow but focused beam into the obscurity that surrounds the precise dating of various cultural events at the palace (for the moment disregarding the year 1776 and opera performances in general) at a time of exceptional significance: the note ‘opera grosse’ for 21 March almost certainly refers to the first performance of Gluck's Orfeo, ed Euridice Footnote 43 – that is, to the beginning of the fifteen-year period of the ‘opera factory’ – while the day before apparently saw the first performance of Haydn's marionette opera Dido.

Apart from Bader's list mentioned earlier, this is the only known document that lists every event, regardless of type, taking place over a certain period – in this case, a fortnight. Kühnel's notes are important not only because of the large number of the accademies – six concerts over a fortnight, the same number as over the whole year of 1778 – but also as a confirmation of the venue. Although one might wonder why ‘with respect to the accademies none of the carpenters have any jobs in the theatre’ – is it because the concerts didn't require any technical preparation of the stage, or perhaps they were not, after all, held in the theatre? – the job that the chief carpenter or one of his workmates was required to do before and after every concert provides a decisive argument for the theatre as the venue for them. There were, or there could have been, candelabraFootnote 44 at every conceivable concert venue in the palace, but if the concerts had been held in the ceremonial hall or in another hall of the corps de logis, or in the picture gallery or, indeed, at any other point of the main building, there would have been no need to light any avenues of trees after the concert (see Figure 8). It is quite obvious that the lamps the foreman was expected to attend to were the ones along the avenue of trees that runs from the privy garden on the western, right-hand side to, and beyond, the entrance to the theatre from the garden; thus the audience could make its way back to the palace safely in the descending darkness. The avenue with a double alley and a pergolaFootnote 45 running alongside would also have provided a safe, well-lit tunnel for those leaving the building.Footnote 46

Figure 8 Another detail from the ‘Sienna plan’. The building in the upper right-hand corner is the complex of the first opera house, a water tower and the Chinese ball-room or ‘Redouten-Saal’ (from left to right). Below this on the right-hand side of the picture, at mid-height, is the ‘Herrschafts-Gebäu’, the guesthouse of the noblemen (for middle-rank aristocrats). The arrows added to the image show how the public, having walked along the illuminated alley, could then turn right and return to the main building, or they could turn left, leave the parterre and then either enter the guesthouse through its main gate, which is clearly visible on the plan, walk to a nearby place or take a vehicle to more distant destinations

The monotonous regularity of the alternating accademies and theatrical performances – put on, as we have concluded, in the theatre – in the first ten days of the highlighted fortnight suggests that this was the normal pattern (note that tragedies were also labelled as ‘Comoedie’ most of the time, sometimes as ‘Trauerspiel’, very rarely ‘Tragoedie’). Concerts outside the theatre – other than those involving chamber music – seem to have been the exception.

All this does not mean, however, that before 1776 Eszterháza would have had a concert performance every other day of the season. Nicolaus the Magnificent had a horror vacui, leading him to make arrangements to have something to do every single day whenever he was staying at Eszterháza. However, it was not possible to achieve this all the time; for instance, according to the overtime accounts, the previous fortnight featured a two-day pause.Footnote 47 It is even more important to bear in mind that over the ten-day period under discussion there was no marionette performance – probably because of rehearsals for the premiere of Dido – even though the marionette theatre had been regarded as one of the favourite kinds of entertainment over the previous three years; similarly, there were no pantomime or ballet performances either. All these types of production, together with – even if not with the same regularity as – opera, had been appearing in the programmes for a considerable time,Footnote 48 therefore it is unlikely that as many as half of the dates would have been available for concerts before 1776.

The inception of the opera seasons on 21 March 1776 – a turning-point – inevitably reduced the relative weight of the accademies, not least because of the sudden significant increase in Haydn's work commitments. Change came on the day of the first performance of Dido: marionette performance, followed by opera the day after, then marionette performance again, and when the next concert finally took place, it had already been five days since the previous one. It is likely that over the week beginning on 24 MarchFootnote 49 there were no concerts at all, because there is not a single date with carpenters’ overtime of six or fewer hours recorded.Footnote 50 However, over the following months this happens frequently: after totting it all up, the likely number of concerts between 28 February and 24 September is fifty-one – naturally discounting any concerts that might have taken place in the prince's residence.Footnote 51 (It seems that in 1776 there were no concerts in the theatre after 24 September.) Since by this time opera performances fairly consistently took up two days a week, Sunday and Thursday, and this was the liveliest year for the marionette theatre,Footnote 52 this number of concert fixtures is probably lower than that of previous years, in respect of which there are no records on which to base such estimates.

Nevertheless, it would be unwise to view Bader's list as a live report of the final decline of concert performances at Eszterháza. There are gaps in the opera schedules later on, too, and specific references to concerts do not cease altogether. For example, Márton Dallos's 1781 rhyming report from Eszterháza mentions music-making a number of times, with special emphasis on the theatre. Stanzas 53 and 54 end with a draft list of the different art forms performed in the theatre, the crowning glory being ‘masterful Music’, in other words concert (and possibly also opera) performances. These stanzas from Dallos, who visited Eszterháza on more than one occasion,Footnote 53 offer further convincing evidence for the accademies’ taking place in the theatre:

Let me just add two much more indirect data to these direct and clear indications. These are rather like the shadows on the wall of Plato's cave if compared with the preceding palpable arguments. However, they are interesting. The first detail in question is found in Nicolas-Étienne Framery's famously unreliable little book on Haydn of 1810, Notice sur Joseph Haydn, which leans on his acquaintance with Pleyel. The relevant story tells of how Haydn presented a new symphony to Prince Nicolaus during one of the prince's not infrequent depressive episodes, hoping, on the strength of previous instances, to bring the prince out of his melancholy with the music. However, the situation was worse than usual, and Haydn's attempt failed: ‘Haydn. . . se tourne vers la loge du prince. . . L'infortuné n'ose plus l'espérer;. . . le prince,. . . toujours silencieux, loin de paraître donner aucune attention à ce qu'on exécute pour lui, affecte de se retirer au fond de sa loge’ (Haydn. . . turns towards the prince's box. The unfortunate man dare not hope;. . . the prince,. . . still silent, without appearing to pay the slightest attention to those who are playing for him, withdraws to the back of his box).Footnote 55 Is it possible that the only true detail of this story is the box, meaning that the concert took place in the theatre?

The other shadow on the wall is, however, the only datum I know of suggesting that a particular famous concert took place in the main building. It certainly comes from a somewhat more reliable source. It is a sentence in Dies's book on Haydn: having finished the performance of the ‘Farewell’ Symphony, ‘Die Virtuosen hatten sich indessen im Vorzimmer versammelt, wo sie der Fürst fand, und lächelnd sagte: “Haydn, ich habe es verstanden. . .”’ (In the meantime, the virtuosos had assembled in the antechamber, where the prince found them and said with a smile ‘Haydn, I've got the point’).Footnote 56 Here the word ‘Vorzimmer’ (anteroom) can certainly be much more easily associated with the main building than with the opera house (unless the musicians were waiting for the prince in the vestibule).

However, the relevance of this evidence may be limited. First, we should note the words of Sigismund Neukomm: ‘Ich bemerke hier daß alle Mittheilungen die ich persönlich von Haydn [habe] (größtenteils aus unseren tête à tête – Tischgesprächen) in frühere Zeit fielen, als die Besuche meines Freundes Dies, in eine Zeit in welcher H. noch kräftig genug um sein Riesenwerk “die Jahreszeiten” zu schaffen.’ (I ought to remark here that all these communications which I received personally from Haydn (mostly from our tête-à-tête conversations at table) occurred in a period earlier than the visits of my friend Dies, in a period when Haydn was strong enough to create his huge work The Seasons.)Footnote 57 In other words, Neukomm tactfully reminds the reader of Haydn's limited capacities during his last years, when Dies was interviewing him. Secondly, Dies's reliability has just suffered a major blow a few lines earlier, when he explains that the ‘Farewell’ Symphony ends with a solo by the last violin player – a mistake Haydn can hardly have committed even in his worst shape. Thirdly, the antechamber motif does not return in any other account of the ‘Farewell’ Symphony, by any author who might have been talking to either Haydn or other witnesses; namely in the accounts by Gregor August Griesinger, Giuseppe Carpani, Carl Ferdinand Pohl,Footnote 58 Framery or by the author of the anecdote published in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung and referred to by Dies in a footnote.Footnote 59

Putting on concerts in a theatre was certainly a practice that Prince Nicolaus experienced in Vienna. Mary Sue Morrow's fascinating monograph Concert Life in Haydn's Vienna suggests that ‘By far the most desirable [concert] locations were the theaters, both in comfort and acoustics’.Footnote 60 (Of course, there were important concerts taking place at other locations, too.) We know for certain that the prince attended concerts held in Viennese theatres, at the very least the Kärtnerthor-Theater (or ‘German theatre’), on the evidence of an invoice for his tickets (see Figure 9);Footnote 61 concert tickets cost one gulden and three-quarters (1 gulden 45 kreutzer), while those for opera performances cost four gulden. Many aristocrats had at their disposal ceremonial halls that could be and often were used as venues for domestic concerts, but private theatres that could emulate the conditions of the best Viennese concerts were rare.

Figure 9 Invoice for the boxes used in the Kärtnerthor-Theater in 1764. Esterházy Privatstiftung Archiv, GC 1764, R 8 F 7 N 37. Used by permission

In fact, the ceremonial hall, today's ‘Haydn-Saal’, in Eisenstadt was not the typical venue for concerts either, at least in the 1760s. We know this because of the Werner–Haydn affair of 1765. In a report accusing his successor of neglectful behaviour, and in order to force Haydn into a more regular pattern of work, Gregor Joseph Werner recommends the restoration of a practice followed during the lifetime of Prince Paul Anton. This involved the musicians giving a twice-weekly (Tuesday and Thursday) accademie during the prince's absence in the officers’ (or clerks’) dining room, a ground-floor space in the remote northern part of the north-eastern tower of the Eisenstadt palace.Footnote 62 However, this was a room modestly furnished for the meals of the higher-rank employees; it may well have been used as the venue for (public?) rehearsals, but was by no means a place to be visited by aristocrats. References to the ceremonial hall as a venue for balls and banquets abound, whereas any unambiguous evidence of its use of a concert hall is missing, and furthermore the great hall is far too big for a group of fourteen musicians, which would have been the maximum strength of the (instrumental) ‘chamber music’ in those days,Footnote 63 and so we are forced to look elsewhere for the genuine Eisenstadt location of Haydn's accademies. The most plausible candidate is the first-floor drawing-room with a balcony in the middle of the southern façade, called the mirror-room today, with – alas, later – stuccos representing musical instruments.

Let us now return to Bader's list of the 1778 performances. He lists six concert dates: 30 January (‘Academie’ with programme), 3 February (‘Academia musica’), 11 February (‘Academie’ with programme), 22 February (‘Academia musica nell’ Appartamento’), 24 and 26 February. (The character of the last two is indicated only by a ‘ditto’ mark that refers to 22 February.) A transcript of this list was published in Pohl's Haydn monograph as an appendix to the second volume, in Gothic script, with (often faulty) added information; it was also published in the German and Hungarian editions of Horányi's Magnificence of Eszterháza, with several mistakes; in English translation it appeared in Landon's book, with some small mistakes, as well as in the English version of Horányi's book, also with mistakes.Footnote 64 Therefore it would seem useful to republish the two concert programmes recorded by Bader, with generous spacing for greater clarity:

d: 30. do [Jan:] Academie,

Synfonia,

Aria v[on]. Me Poschwa,

Concert von Mr Hirsch,

Aria v. Mr. Dichtler,

Sonata v. Mr Luigi [Tomasini],

Synfonia v. Vanhall,

Aria v. M. [Mademoiselle] Prandtner,

d[ett]o v. M. Bianchi,

Synf.

d: 11n ij.Footnote 65 Academie,

Sinfonia,

Aria M. Bianchi,

Conc: M: Rosetti,

Divert: v. M. Pichl,

Aria v. M. Dichtler,

Conc tino v. Pichl,

Aria v. M. Bianchi,

Sinf: von Mr. Hayden.

As we can see, during the two accademies nine and eight pieces were performed respectively, almost half of which were symphonies and concertos; less than half the programmes consisted of arias; and there were also a few instrumental pieces, of the character of chamber music, one (violin) sonata and a divertimento. The names of the singers and instrumental soloists are always listed – Zacharias Hirsch played the flute and Antonio Rosetti the violin – but the names of the composers of the symphonies, Wanhal and Haydn, only appear twice out of five occasions; it is possible, of course, that the other three symphonies were also by Haydn. Bader also gives the name of composer Wenzel (Václav) Pichl with reference to a divertimento and a concertino.

After six concerts held over three and a half weeks, the series came to an abrupt finish at the end of February. In the meantime, similarly to the start of the following (year's) season, the opera season began on 1 February but was interrupted on 5 February, resuming five weeks later on 12 March. Although there was a ten-day break in performances in February and a fortnight's pause over February and March (probably because of the absence of the prince), the overall impression is that the six concerts and two pantomime performances – the latter also being absent as a genre over the rest of the year – fitted into the schedule in the early part of the year because the ‘opera factory’ was not yet in full swing. Later, however, the schedule became very full, in spite of the prince's numerous brief absences. Suffice it to mention that over the eighty-nine days – or nearly thirteen weeks, or a quarter of a year – between 20 April and 17 July there was a performance every single day: plays, operas and (only two) marionette shows. For accademies at whatever venue, even including the prince's private quarters, there was simply no time, since (as we have seen) the performances took up the entire evening: they were unequivocally evening events, as the foreman's lighting instructions prove, and lasted at least two hours, as illustrated by the surviving programme listings.

In this respect it pays to review the activities of Johann Schellinger (or Schilling or Schillinger: he himself spelled his name in different ways), theatrical prompt and opera copyist, since he did much more than copy out operas. It has been known for quite a while that the summaries of his copyist activities over the decade and a half of regular opera performances have largely survived. In these documents Schellinger lists the work he has completed according to the titles of the operas or according to the genre of the pieces. Luckily for us, on top of his modest basic salary, Schellinger was paid for the copies piece by piece, and so there is documentation of his work; by contrast, the three copyists by the name of Elßler, father and two sons, who worked not for the director of the opera house but for the composer Haydn as his trusted collaborators, were paid a fixed monthly sum for copying.Footnote 66 On the occasions when Haydn commissioned copying for his private use he probably paid them himself, without paperwork, and therefore the extent of their copying activities can only be surveyed in terms of the music we recognize as copied by them or, rather, of the surviving portion of these copies.

Table 1 is a summary of the sheet music copied by Schellinger that does not belong directly to any opera, puppet show, ballet, play or pantomime performance (the right-hand column has the number of completed ‘sheets’ (‘Bögen’) or four-page booklets).

Table 1 Non-theatrical music copied by Johann Schellinger

Notes:

a ‘Atre’ is being used as a noun, meaning a trio (‘a tre’); my thanks to Balázs Mikusi for solving the riddle.

b This gap of three and a half years is hard to explain, since this kind of discontinuity of information is quite rare in the relevant archival material. For example, the bills relating to the duties (during the opera performances) of the ladies’ and the gentlemen's tailor and of the hairdresser have been preserved completely from the spring of 1777 until 1790; the accounts for supernumeraries (called ‘Stabenen-Ausweis’) are also preserved in their entirety from the beginning, in October 1779, and amount to several hundred documents. As to Schellinger, Landon (Haydn at Eszterháza, 67) makes a mention of a contract from 1780 (EPA, ED N 1299 (5 October 1780)), though he fails to mention his source; nevertheless, Schellinger already appears in various lists of allotments in kind and payments, first as ‘Copist’ and then with his full name, from 1776. The contract just mentioned was definitely made with him in his capacity of prompter, as this is the first document where he is mentioned as ‘Souffleur’ (compare, among others, EPA, Schafferey Süttör Rechnung (SS) 1776 N 51, Acta Varia (AV) F 291a, GC Handbuch 1778 f. 97–98, Rent Amt Süttör Rechnung (RS) 1779 N 117). In fact, we know of a bill for copying of instrumental music that was completed during this three-year period: EPA, GC 1780 F 9 R 17 N 55½ tells us that the cellist Anton Kraft has copied twelve trios and six quartets, adding up to eighty-nine sheets, though the exact purpose of the copying is not clear.

c The title of this document highlights especially clearly that operas and symphonies were connected to the same venue: ‘Was für den hochfürstlich. Theat: an opern und Sinfonien ist copiret worden von 1 Juny bis 12 Decemb. 782’ (What has been copied for the High Princely Theatre from among operas and symphonies between 1 June and 12 December 1782).

d Symphonies by various authors.

e That is to say, over the years 1784–1790 Schellinger no longer copied either instrumental pieces or arias.

EPA = Esterházy Privatstiftung Archiv, Burg Forchtenstein

RA = Rentamt Eisenstadt

GC = General-Cassa

A. M. = Acta Musicalia

BC = Bau Cassa Süttör

Note that in the case of those documents that were removed from the Forchtenstein archives between the two World Wars ‘Esterházy-Archiv’ is used, as when they were still being held there the name ‘Esterházy Privatstiftung Archiv’ did not yet exist.

We can see that symphonies and (concert) arias dominate; other than these, there are pieces for baryton (up till 1777) and a series of minuets by Haydn, which may have had various uses. It seems reasonable to conclude that what we are witnessing here is the production of sheet music for the accademies, confirmed by the actual wordings of the list: ‘Sinfonie(n)’ is mostly accompanied by ‘pro/per/di T(h)eatro; and ‘Arie’ is followed in every case by ‘di accadem[ique]’. So far, so good: we showed earlier that the venue for the ‘Accademien’ was the ‘Teatro’.

But what might be the explanation for Schellinger's consistent, and somewhat disconcerting, habit of referring to the theatre – and never to concerts – in connection with the symphonies, even though he does refer to concerts in relation to arias? Surely, symphonies would have dominated the programmes of the accademies. We find the explanation in a hitherto-overlooked sentence of the oft-quoted Excursion, describing an opera production: ‘à l'instant que le Prince paroit dans sa loge, le coup d'archet se donne & aprés une Simphonie dans le dernier goût, on est enchanté par le spectacle’ (the moment the prince appears in his box, the bows hit the strings, and after a symphony in the latest fashion all are enchanted by the performance).Footnote 67 This suggests that the opera performances (or at least part of them) were preceded by the performance of a symphony played either before or instead of the operatic overture.

The authenticity of this description is beyond reasonable doubt because it reflects the common Viennese practice of the time, and the practices in Vienna constituted a natural model both for Haydn and for Prince Nicolaus. We know that the practice of playing symphonies in the intervals of singspiel performances existed in 1781, when a German traveller reported: ‘Ich bin sehr aufmerksam gewesen, nicht allein in Singspielen, sondern auch auf die Symphonien zwischen den Akten, auf welche die Zuhörer gewöhnlicherweise so wenig Acht zu geben pflegen. Es fügte sich, daß ich verschiedene Symphonien von Haydn und Vanhall hörte, die ich in Berlin oft gehört. . . hatte.’ (I was very attentive, not only in the Singspiele, but also to the symphonies between the acts, which the audience normally pays so little attention to. It so happened that I heard various symphonies by Haydn and Wanhal that I had often heard in Berlin.)Footnote 68 It is worth noting that this account names, yet again side by side, the two known composers of symphonies played at Eszterháza accademies. Further, Morrow treats this practice as self-evident with respect to operas proper.Footnote 69 A similar practice still seemed to exist a decade and a half later in 1797 at the Freyhaus Theater an der Wien. Between the acts of Haydn's Armida, a genuine opera which was being given a concert performance for a charitable cause, a symphony by Mozart was heard: ‘Im Zwischenakt eine Symphonie von Mozart’ (In the intermission a symphony by Mozart).Footnote 70 But it seems that fine distinctions between different genres were not made: in her book Morrow writes, without specific reference: ‘Symphonies were very much in demand since each virtuoso concert included two or three and every oratorio generally opened with one, not to mention the countless works that served as intermission fillers in the theaters.’Footnote 71 (Actually, the snapshot of the Excursion might also have described the events of an intermission in the theatre.)

We also have data about a symphony in a Viennese theatre directly connected with Haydn, even if at a somewhat later date. On 21 September 1795, not long after Haydn's return from his second London sojourn and obviously with his approval, one of his final London symphonies was performed in Vienna. It took place in the Burgtheater as part of an evening consisting of spoken plays, as Count Zinzendorf's well-known diary informs us: ‘Au spectacle. Der Jurist und Bauer. Symphonie de Hayden de Londres avec les tambours.’ (At the theatre. The Lawyer and the Peasant. London symphony by Haydn with drums.)Footnote 72

The information given by the Excursion also looks convincing because we have here two pieces of evidence, in themselves of doubtful meaning and value, shedding light on one another, so they possess a considerably more precise meaning and more cogency together than they used to have separately. For what firm conclusions could be drawn from the music copyist's consistent references to the theatre when describing symphonies he copied, which have connections both with theatre and with concerts? Not much. But if we know of the practice of performing symphonies before opera performances, his choice of words takes on a different significance: in this context the 1,300 sheets, some 5,000 pages’ worth of copy, proves the existence of an established practice rather than a one-off occasion in 1784. All this increases the weight and validity of the Excursion reference. The quantity of the copied material also dispels any lingering questions, perhaps generated by the ambiguity of the term ‘sinfonia’, about the music in question being nothing more than ‘normal’ operatic overtures.Footnote 73 It is not possible for this to be the case because, just for example, the 493 sheets, nearly 2,000 pages, of music copied in the period between November 1776 and May 1777 exceeds several times over the combined length of the overtures of the ten or so operas that were performed at the time. The likelihood of producing copies of overtures in such quantity is cast into further doubt by findings in the Esterházy sheet-music inventory of 1858:Footnote 74 only thirty-four separate operatic overtures are listed, including those of Singspiele and of music accompanying plays; in any case, most of this material dates from a later period and only two or three of the pieces can be connected with performances at Eszterháza. One should also not assume that copies of overtures have disappeared from the library in large quantities: most of the full scores and the parts of the overtures needed for the opera productions are to be found together with the rest of the performing material.

We can also rule out the possibility that these ‘Sinfonien vor d. Theater’ might have served as incidental music to (spoken) plays and would be equivalent to the category of ‘theater symphonies’ proposed by Elaine Sisman. In fact, ‘theater symphonies’ and ‘Sinfonien vor d. Theater’ are two strikingly similar terms with entirely different meanings. Sisman's ‘theater symphonies’ relate to a very limited number of symphonies by Haydn, written not later than 1774, in which musical material that might have been specifically composed for the stage appears. By contrast, Schellinger's term refers to a large number of symphonies by various composersFootnote 75 covering some 5,000 pages and copied between about 1775 and 1783. Beyond the realization that such a large quantity of sheet music is likely to account for the entire set of symphonies over the period – in other words, all symphonies are ‘appropriate for the theatre’ – the decisive argument is to be found in Schellinger's second invoice of 1777 (Figure 10).Footnote 76 As well as 284 sheets of symphony copies, this invoice lists the musical material of a dozen theatrical pieces of different kinds, including those of four German plays. This makes it clear that the very notion of ‘Sinfonie vor d. Theater’ does not include any kind of incidental music for the theatre. This leaves only one role for the symphonies: that of being performed as introductions (and possibly also as intermission entertainment, according to the Viennese custom) to opera performances as independent pieces, as reported in the Excursion.

Figure 10 Schellinger's second invoice from 1777. Esterházy Privatstiftung Archiv, GC 1777 F 14 R 20 N 21. Used by permission

A tally of copied sheets reveals an order-of-magnitude difference between the lengthier symphonies and the naturally shorter arias. It also becomes clear that after the three-and-a-half-year-long hiatus from autumn 1777 to spring 1781 Schellinger no longer copied arias; in fact, this was already the case in the middle of 1777. Vocal music must by then have disappeared from the programme of the accademies. (It is possible that, starting in 1777–1778, the ‘theatre symphonies’ gradually took over the function of the accademies, thus the performing of symphonies became part of the opera performances, a hypothesis reinforced by the evidence of Bader's list, reflecting the decline of the accademies proper.) From 1781 on, copying of symphonies continued for another three years, even if at a third to a fifth of the productivity of 1776–1777. Schellinger's swansong as a copyist of instrumental music was the nineteen sheets of music – probably the material of a single symphony – in 1783, suggesting that the performing of symphonies at Eszterháza, whether at concerts or in connection with operas, had reached its final stage around this time. (It is therefore surprising to have an explicit mention of a symphony in connection with an opera performance precisely in the year 1784, by which time the stream of performing material must have ceased. Could it be that by then theatre symphonies were performed on rare occasions only, using existing copies of music? Or did they use ready-bought copies of music? Future scholarship will, hopefully, provide answers.)

If we cast a glance at the 1783 accounts for supernumeraries,Footnote 77 we will not find the decline of the accademies astonishing. As well as the operas, the accounts for 1782 to 1785 include all theatrical productions that required staging – that is, stagehands and supernumeraries – but nothing else. Hence, in contrast to Bader's summary of 1778, which does not deal with money matters, there is no mention of accademies. Nevertheless, the two documents give the same impression: opera and spoken theatre seem to have squeezed out all other genres of entertainment.

It is also quite improbable that accademies took place and were simply left off the list: weeks with three nights of opera and with four of spoken theatre follow each other, sometimes filling up a full month like March (after the beginning of the season) or October 1783. During the whole season – apart from the obvious interruption between 12 and 20 April, including Holy Week, and the probable programme break between 12 and 15 September – there occurred only ten (maybe eleven) ‘empty’ days. Some or all of these may easily represent accademies, but even if that were so, the concerts would have represented at most four per cent of the season's performances. Later, from 1786, the dates of performances other than opera disappear from the accounts of the theatrical supernumeraries, and so we don't know how full the diary was; but it seems clear that by then a practice of regular concerts no longer existed.

All this is in agreement with our understanding that around this time Haydn stops composing symphonies for local use. Symphony No. 73, ‘La chasse’ (composed at the latest in 1782, but probably in 1781),Footnote 78 is followed by the series of Nos 76, 77 and 78. According to the generally accepted hypothesis, it is these pieces that Haydn refers to in his letter of 15 July 1783, mentioning three symphonies composed in the previous year and connected with his planned visit to England.Footnote 79 The following three symphonies, Nos 81, 80 and 79 (in the probable order of their composition) also form a unit; Haydn may well have started composing them in 1783, completing the last of the three in the autumn of 1784. Both sets were published in several places, both singly and in their entirety. Of course, there is no reason for these symphonies not to have been performed at Eszterháza if, and as long as, accademies were still taking place, as the scoring certainly permits this. However, these compositions no longer substantiate the existence of such concerts: the intent of publishing them and the possibility of their performances as ‘theatre symphonies’ – perhaps even on the occasion immortalized in the Excursion – is reason enough for their creation.

Sonja Gerlach, the editor of the volume containing these six symphonies in the Joseph Haydn Werke complete edition, is of a different opinion. In the Introduction she emphasizes that Haydn would have been considering publication from the start:

The grouping into two series arises from the transmission itself. Haydn disseminated the new symphonies himself, in the first place in the usual grouping of three works at a time, and sold them to specific publishers.

Subsequently, however, she states:

Nevertheless, it is out of the question that Haydn should have composed the six symphonies specifically for publication. His main task remained the entertaining of his employer Prince Nicolaus Esterházy with new music. His symphonies had to comply with the prevalent composition of the court orchestra and had to be suitable for an orchestra of 25 to 30 instrumentalists.Footnote 80

At the end of 1784 and the beginning of 1785 the number of instrumentalists in the Eszterháza orchestra was at most twenty-four.Footnote 81 Therefore if these symphonies required at least twenty-five musicians, then they were not adjusted to the conditions of the orchestra, which should raise serious doubts about the assertion that in 1784 Haydn's ‘main task’ should still have been ‘to entertain’ the prince ‘with new music’.Footnote 82 It is enough to cast a cursory glance over the dense programming of 1782 to 1784, including the first performances of Orlando paladino in December 1782 and of Armida in February 1784, to realize that the real question is whether by this time Haydn was obliged to compose anything other than operas for the court. The plausible answer to the question is no. This finds an echo in Haydn's second contract – dated 1 January 1779 – in which the prince effectively relinquishes his rights over Haydn's compositions.Footnote 83 Moreover, Armida marks the end of his Eszterháza opera compositions: afterwards Haydn only composes insertion arias for domestic use.

All this is, however, no more than a storm in a teacup: the six symphonies we have been discussing are followed by the six ‘Paris’ Symphonies, composed unequivocally in response to external commissioning, and thus the more than two decades of writing symphonies for Eszterháza's in-house entertainment comes to a definite end.Footnote 84 If we inspect the contemporary concertos as well, we find that the D major cello concerto (hVIIb:2), written for Anton Kraft and therefore meant for Eszterháza, was composed in 1783; the lost concerto for two horns (hVIId:2) probably dates from no later than 1784, and the last keyboard concerto, the popular D major one (hXVIII:11), cannot have been composed later than 1784. Therefore we have to conclude that Haydn's last compositions for the Eszterháza accademies were written in 1783 or, at the latest, in 1784. Considering how clearly the ‘Paris’ Symphonies were intended for publication and that we can only be certain of the copying of one symphony and the composing of one concerto in 1783, I would venture that the last accademies are most likely to have taken place in 1783.

To complete the list of the instances of music-making known to us, let me just briefly refer to Haydn's widely known letter written to Marianne von Genzinger on 14 March 1790, making mention of a very specific and intimate musical event. In this letter Haydn describes how he and his musicians tried to console the afflicted Nicolaus just a couple of days after his wife's death:

der dodtfall Seiner verstorbenen gemahlin drückte dem Fürsten dergestalt darnieder, daß wür alle unsere Kräften anspanen musten, Hochdenselben aus dieser schwermuth herauszureissen. . . Der arme Fürst verfiel aber bey Anhörung der Ersten Music über mein Favorit adagio in D in eine so tiefe Melancoley, daß ich zu thun hatte, Ihm dieselbe durch andere stücke wider zu benehmen.

The death of his wife so crushed the Prince that we had to use every means in our power to pull his Highness out of this depression. . . but the poor Prince became so depressed when he heard my favourite Adagio in D that we had quite a time to brighten his mood with the other pieces.Footnote 85

Alas, any reference to the location is missing here; we cannot even try to guess it, as the size and composition of the ensemble are also unclear.Footnote 86

By way of an acknowledgement that this paper may not have clarified, once and for all, the questions surrounding the venues for the Eszterháza concerts and the time-span over which they took place, I will finally quote from a surprising, even disconcerting, document. Since the word ‘accademie’ disappears altogether after 1779, including accounts concerning theatrical supernumeraries, it is very surprising to encounter the Stabenen-Ausweis dating from April 1789,Footnote 87 the penultimate year of Eszterháza's golden age (Figure 11). It records three accademies taking place on three consecutive days, as if references to the accademies had never disappeared from the records. However, the situation is, in fact, even more peculiar than it seems to be at first sight: 9, 10 and 11 April fell on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Saturday of Holy Week in that year. Palace observance did, indeed, lose a great deal of its initial piety over the years: while in the first years the entire Holy Week, including Easter Sunday, was spent without programmes (as we have seen for 1776), from 1784 – four years after the introduction of three regular opera performances (Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays) per weekFootnote 88 – Tuesday of Holy Week and Easter Sunday found their way into the opera schedule.Footnote 89 We have to presume that the Roman Catholic prince's household did not eschew religious tradition to such an extent as to perform symphonies, sonatas or even secular arias instead of the lamentations intended specifically for these three days of the year. But if we further presume that the accademies contained devotional music, where would they have taken place? Were they put on in the theatre, whose acoustics are nothing like that of a church, in a move verging on blasphemy? Or in the tiny chapel, which did have a small positive organFootnote 90 but had never featured in any document relating to music-making? Or in the more appropriate venue of the Eisenstadt palace chapel, whose expenses had never appeared in the Eszterháza Bau Cassa? In any case, why is there mention of it in the supernumeraries’ accounts if there are no associated costs? Finally, if there is a record of these accademies, why is there no mention in the same place of the concerts which we are inclined to think were put on in 1782 and 1783? Is it possible that Holy Week lamentations were a regular custom at Eszterháza, but that – as with other, secular accademies – they were left unmentioned? Or maybe, quite the other way round, this piece of information from 1789 could be used to prove that – in contrast with what has been said and thought before – separate accademies were no longer put on in 1782–1783, as they would have appeared in the accounts for supernumeraries? To be sure, this might also mean that the concertos composed in those years must have been performed in the course of the opera performances – which, in fact, would not be at all unprecedented.Footnote 91 (As we have seen, the concert arias had very probably disappeared by then anyway.) I have to admit that, for the moment, I have no answer to these questions.

Figure 11 Detail from the accounts for theatrical supernumeraries, April 1789. Esterházy Privatstiftung Archiv, BC 1789 N 444. Used by permission

In summary, our virtual tour, in space and time, of the Eszterháza palace during its golden age may have helped us understand the logic of the use of various venues, as well as revealing to us the custom of starting an opera performance with a symphony – a practice that may well have taken over the role of the gradually declining accademies.

Several accounts confirm that not only were the theatre and operas (and almost certainly the concerts as well) put on by Nicolaus the Magnificent free to attend, but also that any- and everybody was admitted – provided, presumably, that they were appropriately attired. (In another part of his poem, stanza 55, Dallos mentions ‘the Peasant . . . with his Mate’ among the visitors to the theatre.) This does not mean that there was no separation between the areas for the general public, those reserved for visiting aristocrats and the prince's (and his lady's) private space. It is well known that the two theatres, the parterre and the pleasure garden were public spaces. But it is most likely that the main building, and especially its central section, was not open to just any visitor, and members of the public would not have been allowed to attend the feast put on for Maria Theresia. It seems sensible to assume that musical entertainment for the higher ranks was provided in the main building – as we have shown, probably mostly in the summer dining hall on the ground floor and in the picture gallery. However, the regular and free-to-attend accademies could not possibly have been held there: their obvious venue was the opera house and the marionette theatre – ‘die beyden Comoedien-Hauser’ – open to the public and hosting a whole range of cultural and entertainment programmes.Footnote 92 For intimate chamber music, especially pieces involving the baryton (and Prince Nicolaus as its player), the prince's private quarters provided a natural setting.Footnote 93 In other words, in the different spaces of the Eszterháza palace, just as in the auditorium of a theatre of the time, all those present had their appropriate place, reflecting their social status; the same must have applied to the different occasions of music-making.

(English translation by Sara Liptai and David Ennever)