Under the entry ‘Pronunzia’ in the Vocabolario Cateriniano of 1717, a dictionary by the librettist Girolamo Gigli (1660–1722) based on language used by Saint Catherine of Siena, Gigli voices some of his many complaints about current academic Tuscan usage:

Per mancanza di stamperie si trascurò dalle nazioni toscane (trattane Lucca) la coltura dell'idiotismo loro, che colla pubblicazione di varie buone scritture sarebbe potuta mantenersi. … Intanto i Fiorentini faceano caminar più torcoli che macine … empierono tutta Italia de' libri presso loro stampati, bandirono nuove leggi d'ortografia, ora sbandendo l'H, ora chiamando la Z a fare l'uffizio del T, ora processando per inutile il Q, ora mutilando tal parola di sillabe, ora tal sillaba di lettere, ora disapostrofando un articolo, ora disaccentando un pronome, ora stirando a due tempi un dittongo, ora mascolinando una voce femmina, ora castrandone e indonnandone una maschia; si veramente che l'alfabeto, dove bastonato, dove scarnito, dove menomato di membri, avesse bisogno che qualche città toscana fondasse per carità uno spedale per li caratteri ormai fatti invalidi nelle scritture fiorentine.Footnote 1

Because of a lack of publishers, the culture of their idiocy is hidden from the Tuscan peoples (except in Lucca), a culture which could have been supported with the publication of various choice writings … While the Florentines fill all of Italy with their books, they announce new laws of orthography, now banishing the H, now calling the Z into the service of the T, now putting the Q on trial for being useless, now mutilating one word of syllables while mutilating another syllable of letters, now disenfranchising an article, now de-emphasizing a pronoun, now stretching a diphthong into two syllables, now masculinizing a feminine word, now castrating and feminizing a masculine word, such that the alphabet, where beaten, where scorned, where maimed of its limbs, would need some Tuscan city to found a charitable hospital for the characters made invalid in Florentine writing.

The masculinization of the feminine and the feminization of the masculine that Gigli so sarcastically describes also serves as a metaphor for the process of gender subversion in his mock-heroic opera L'Anagilda, ovvero La fede ne' tradimenti of 1711. Gigli created L'Anagilda by revising his earlier libretto, La fede ne' tradimenti (Siena, 1689). The original La fede ne' tradimenti was among twenty librettos and plays composed by Gigli for the Collegio Tolomei, a Jesuit school in Siena. After being repeated in Siena, it was performed in various other cities prior to the Roman premiere under its new name. The subsequent performances took place in Siena (1689), Bologna (1690), Lodi (1695), Florence (1696), Mantua (1697, 1699), Luxembourg (1701), Verona (1703) and Venice (1705). Each of these productions was revised by a different author, often not named in the libretto. Gigli was involved in only the original 1689 Siena libretto and the revised 1711 L'Anagilda.Footnote 2

Gigli's revisions are striking because L'Anagilda was commissioned by Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli, an important patron, member and host of the Arcadian Academy. This society, which was founded in 1690 to improve Italian literature, believed that modern opera ought to imitate ancient Greek tragedy. Although it is likely that L'Anagilda was performed for an Arcadian audience, Gigli's revisions contradict the Academy's aesthetics. Instead of following Arcadian prescriptions for reform, Gigli adds comic material to L'Anagilda and intensifies the mock-heroic elements already present in the original La fede ne' tradimenti.

In L'Anagilda the parodic treatment of the protagonist's heroic values subverts his traditional gendered position in relation to two strong female characters, who ultimately usurp the heroic role. Such characteristics mark the opera as part of a literary genre known as the mock heroic, a genre that simultaneously invokes and satirizes heroic ideals. In the case of L'Anagilda, Gigli uses the satirical mode of the mock heroic to flout yet, paradoxically, to illuminate problematic elements of Arcadian reform. Furthermore, Gigli's use of the mock heroic in this opera represents a taste for satire that spanned his entire career. His sardonic approach to literature, theatre and opera, combined with his insistence on criticizing current trends in the Tuscan language, preferring instead to promote his native Sienese dialect, eventually placed Gigli in a serious political conflict with three of the prevailing literary academies with which he was associated – the Intronati, the Cruscanti and the Arcadians – and caused him to lose his professorship at the University of Siena.

This article will trace a brief history and description of the mock-heroic genre, in order to demonstrate Gigli's use of the genre's characteristics in L'Anagilda, and will establish the mock heroic as Gigli's satirical way both to condemn Arcadian reform and to highlight paradoxical tendencies with Arcadia itself. Finally, this essay will show how the new score for L'Anagilda, composed by Antonio Caldara, enhanced the opera's verisimilitude.

I

The goal of the Arcadian Academy was to refine Italian literature by eliminating the excesses of the seventeenth century as exemplified by Marino and mannerism and thereby to return to the ‘pure’, ‘natural’ style of Dante and Petrarch. United with this agenda was a desire to reconnect with Italy's classical heritage. As Gianvincenzo Gravina wrote in his first treatise on verisimilitude and literary aesthetics:

quel che i greci filosofi hanno avvertito e ridotto a vere cagioni, caduto nelle mani d'alcuni retori, sofisti, grammatici e critici scarsi di disegno e di animo digiuno ed angusto, è stato da loro contaminato e guasto.Footnote 3

That which the Greek philosophers have advised and reduced to true causes, having fallen into the hands of some rhetors, sophists, grammarians and critics deprived of creativity and possessing a starved and narrow intellect, has been [subsequently] contaminated and destroyed by them.

By returning to Italy's classical past and renaissance humanism and by reacting against the most recent trends in Italian literature, the Arcadians sought to promote ‘good taste’ in the arts and sciences. Although there was no single, united approach among the Arcadian theorists, much of the early Arcadian criticism advocated a neo-Aristotelian approach to serious drama, involving the elimination of supernatural influences and effects, a reduction in arias that distract from dramatic narrative, a focus on verisimilitude and, finally, the strict adherence to one genre, typically either pastoral or tragic.

At first glance L'Anagilda seems to have the pedigree of a true Arcadian opera: its librettist, composer, patron and performance setting were all within the realm of the Academy. Gigli, as I have mentioned, was a member of the Arcadian Academy. Antonio Caldara, though not an official member of the Arcadian Academy, collaborated with Arcadian librettists for much of his career – later, in Vienna, he worked almost exclusively with Apostolo Zeno and Zeno's successor Pietro Metastasio, both renowned for their structural reform of the libretto. However, it was as maestro di cappella (1709–1716) to Francesco Maria Ruspoli that Caldara first came into contact with Arcadian ideals. In 1711 L'Anagilda was performed at Ruspoli's palazzo, which had been established in 1707 as one of the Academy's weekly meeting places for concerts and literary discussions – its bosco Parrasio, or Parrhasian grove.Footnote 4 From conception to realization, this work should have reflected the values of the Arcadian Academy's literary reform programme.

Upon closer inspection, however, one realizes that the text of this seemingly Arcadian work conflicts with the aesthetics of the society in several respects. Gigli includes a surprising array of non-Arcadian plot elements: the libretto's capricious twists and turns, deceits, transvestite posturing, comic interludes and fantastic intermezzos represent virtually all of the elements despised by the Arcadians. In his Preface to L'Anagilda, Gigli explains that the opera has been performed in many other Italian cities, but he has made several changes for its appearance in Rome. A comparison of Gigli's Prefaces from the 1689 and 1711 versions of the libretto will demonstrate how he viewed the restructuring process, and the new work's relationship to contemporaneous Arcadian ideals.

Although the earliest version of the libretto, La fede ne' tradimenti (Siena, 1689), does not incorporate either comic scenes or intermezzos, Gigli clearly regretted the lack of humorous frivolity. He apologized for this lacuna in his 1689 Preface, blaming his negligence on insufficient time:

questo mio Dramma è parto di poche settimane. Se poi leggendo questi poveri fogli ti paresse, che una Storia di maggiori accidenti apparisca quasi un aborto, mentre l'ho ristretta a quattro soli Personaggi, sappi; è stata necessità non elezione. E l'istessa ragione m'ha proibito di dar luogo fra questi pochi soggetti al ridicolo; per fine ti prego a compatirmi, come hai fatto per l'addietro.Footnote 5

My drama is the product of a few weeks. If then in reading these poor leaves it should seem that a story of greater incident appears almost aborted, while I have restricted it to only four characters, know that it was out of necessity rather than choice. And the same reason prevented me from making room among these few characters for the comic; in the end, I pray that you will sympathize with me, as you have done in the past.

Gigli's contemporaries agreed that the libretto needed comic action: at least five of the subsequent versions of the libretto (the Florentine, both Mantuan, the Veronese and the Venetian productions) each added two comic characters, with each version representing new material. It is not surprising that in 1689, one year before the founding of the Arcadian Academy, Gigli would address this issue in the Preface to La fede ne' tradimenti. His comments in the 1711 version of L'Anagilda are completely out of keeping with the Arcadian agenda.

In the 1711 libretto Gigli explains the changes he has made for the opera's appearance in Rome. He has included new arias in order to ‘better adapt [the text] to modern usage’, and, at Ruspoli's request, he has added intermezzos for the two buffo servants drawn from the primary cast of characters, in adherence to what Gigli calls the ‘Venetian tradition’:

Quest'Opera, che tante volte è comparsa in diversi Teatri d'Italia, si fa vedere adesso in Roma con qualche piccola mutazione, e giunta di Ariette, colle quali ha stimato di ravvivarla, e meglio adattarla all'uso d'oggidì il suo medesimo primo Autore. Egli, per comandamento del Generoso Personaggio, che la fa rappresentare, ed a cui si fa pregio di servire attualmente, ci ha tramezzate due Parti ridicole affatto sciolte dal nodo del Dramma (siccome oggi si pratica nelle Scene di Venezia, ed altrove) colle quali s'intrecciano gli stessi intermedj, di piacevoli invenzioni di danze, e comparse, al maggior divertimento composti.Footnote 6

This work, which has appeared many times in various Italian theatres, is now shown in Rome with some minor alterations and additional arias with which the original author has sought to enliven it and better adapt it to today's usage. The author, by request of the generous personage who is bringing it to the stage, and whom it is a privilege to serve, has inserted two comic characters pulled from the narrative thread (as now is done on the Venetian stages and elsewhere), around whom the intermezzos themselves, composed of delightful dance inventions and apparitions for greater entertainment, are woven.

It is surprising that these non-Arcadian elements would have arisen at the specific request of Ruspoli, the patron of an Arcadian bosco.Footnote 7 Furthermore, Gigli's use of the mock heroic, a genre not supported by the Arcadian Academy, ultimately subverts the group's literary reform principles for an audience that holds those principles as both its highest value and its patriotic duty.Footnote 8

Much of what Gigli has added to L'Anagilda reflects the trajectory and interests of his career. Gigli was one of three important comedic dramatists who worked in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Tuscany, the others being Giovan Battista Fagiuoli and Jacopo Angelo Nelli. As a result of the repressive censorship of Cosimo III de' Medici, these creative dramatists were mostly restricted to the smaller theatrical spheres sponsored by academies and private patrons.Footnote 9 Although Gigli was certainly very knowledgeable about the resurgence of classical thought pervading the academies to which he belonged and was highly educated in classical literature, he never entered the field of serious or tragic drama based on classical models, nor did he aspire to do so. Gigli's career, strictly rooted in comic traditions, was bifurcated according to the influences he received: the first half was primarily influenced by Spanish theatre, comedy and literature, while the second half was primarily influenced by French comedy, especially by the works of Molière. Gigli's comments in the preface to L'Anagilda seem to reflect the somewhat specific range of his usual target audiences and his intense interest in the comic tradition.

Gigli's comments about his new arias and intermezzos – his intention to please modern audiences and to adhere to the ‘Venetian tradition’ – testify to his concern first and foremost to entertain and, secondarily, to interact with traditions outside of the narrowly defined Roman, Arcadian sphere.Footnote 10 We can see in the revised libretto Gigli's desire to modernize and broaden his dramatic usage: he added new arias to flesh out characterizations and strengthen the drama, though he kept most of these within the limits of the early eighteenth-century reform libretto structure, and he maintained a formal boundary between the purely fantastical intermezzos and the drama per se. As my argument unfolds, we shall see how Gigli's new arias create greater realism, providing an alternative path to verisimilitude, and how he turned to the mock heroic as a literary tradition that could proclaim classical values just as well as the pastoral and tragic traditions officially supported by the Arcadians.

II

The genre of the mock heroic openly flouts Arcadian ideals. The mixture of the serious and comic in one work, a distinct narrative implausibility and a perceived lack of good taste all made Arcadians look down on the genre.Footnote 11 The Arcadian Academy dismissed all forms of satirical fiction and, because of its experimental nature and its departure from the classical style, specifically rejected the idea of the mock heroic.Footnote 12 Giovanni Maria Crescimbeni and Gravina in particular were vocal in their distaste for the genre. Crescimbeni discusses the mock-heroic style in his Commentarii intorno all'istoria della volgar poesia.Footnote 13 He makes little distinction between various types of comic writing, such as the novel, satire, parody or the mock heroic, but considers them all to belong to a single burlesque type with sixteenth-century origins.Footnote 14 Gravina takes an even stricter position in his Della ragion poetica of 1708, considering the mock epic a base form of the novel that deserves neither the appellation ‘epic’ nor ‘narrative’.Footnote 15

Despite their agreement on the mock heroic, these two prominent scholars diverged regarding their visions for Arcadia. Their heated and very public argument ultimately led to the Arcadian schism of 1711. When all reconciliation seemed impossible, Gravina and his followers founded a new academy, at first called La Nuova Arcadia, later the Accademia dei Quirini. Although their primary disagreement ostensibly stemmed from a dispute over the authorship and procedures of the Arcadian constitution, the leges Arcadum, other factors may have been in play. For example, some scholars have suggested that while Crescimbeni advocated the Petrarchism, pastoralism, sonnets, lighter-themed works and improvisatory practices that were common in Arcadia, Gravina increasingly became convinced that Arcadia's greatness would lie in its replication of ancient Greek tragedy.Footnote 16 Another scholar has suggested that Gravina's negative perception of frivolity within Arcadia may have been representative, at least in part, of his seeming discontent concerning the admission of women and dilettantes.Footnote 17 In either case the year 1711 certainly provided a fragile context for the kind of satirical writing that Gigli offered. At a time when the core of the institution and the direction it should take were being hotly contested, Gigli's promotion of the mock heroic seems aimed at deepening the rift, or, at least, at adding a performative critique to the mix. In this light, Gigli's use of the genre for an intimate Arcadian audience seems quite controversial and provocative.

In order to understand Gigli's unusual and innovative use of the mock heroic in L'Anagilda, let us look briefly at earlier precedents and sources of inspiration. The combination of comic and serious elements characterizes a long line of renaissance Italian poems. They are sometimes called medley epics or serio-comic romances, use epic language to describe trivial or everyday events and are considered precursors to the seventeenth-century tradition of the mock heroic. Some examples of this renaissance tradition are: Luigi Pulci, Morgante Maggiore (1460–1483), Matteo Maria Boiardo, Orlando Innamorato (1472–1495), and Lodovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso (1516–1532).Footnote 18

Of seventeenth-century works, three have emerged as prototypes and masterpieces of the mock-heroic genre, two of which preceded Gigli's opera: Alessandro Tassoni's La Secchia rapita (1622), Nicolas Boileau's Le Lutrin (1674–83) and Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (1712–1714). Each of these authors claimed that he had founded a brand new genre. For example, Tassoni considered his work a new invention that mixed the serious with the burlesque, while Boileau considered his work a new type of burlesque in which ordinary people use the language of Dido and Aeneas, unlike earlier burlesques in which heroic characters use the ‘low’ language of the everyday.Footnote 19 Modern scholars often treat Boileau's Le Lutrin as the most influential work in the ‘new’ mock-heroic genre, since it had a direct influence on Pope's The Rape of the Lock, which itself spurred a number of direct imitations.Footnote 20 These works share two common elements: an inflation of seemingly trivial subject matter to the language and proportions of classical epic poetry, and a plot that is at least partially based on historic or recent events, but whose reality is masked by its overblown treatment.Footnote 21

Another important seventeenth-century precedent displaying the mock-heroic mode is Cervantes's Don Quixote (two parts, 1605 and 1615); while most scholars of the seventeenth-century mock-heroic genre have focused on the aforementioned authors, Cervantes also had a lasting effect on European comic traditions. The tradition of Don Quixote as a mock-heroic figure differs significantly from the others mentioned above. Rather than create an epic out of trivial events, Cervantes trivializes epic events through parody and satire. Don Quixote becomes mock heroic because of the incompatibility of his character with his environment, and because his heroic idealism is so severely inconsistent with the reality of the narrative:

The world of the Cervantine mock-hero is unamenable, sometimes positively hostile to his aspirations, not hostile as in tragedy, where fate must inevitably and finally thwart the endlessly aspiring will, but hostile or indifferent to the very idea of the heroic, providing no real medium for its complete and authentic expression.Footnote 22

A severe disjunction between the realities of the protagonist and those of the narrative, resulting in various forms of madness and transformation, constitutes what several scholars describe as the rhetorical essence of all mock-heroic poetry.Footnote 23 Three linguistic and narrative figures contribute to the rhetoric of disjunction, madness and transformation found in the mock heroic: oxymoron, paradox and periphrasis. Oxymoron and paradox both juxtapose two irreconcilable concepts, whether on a small or a large scale: grand and trivial, real and implausible, or heroic and un-heroic may stand side by side.Footnote 24 Similarly, periphrasis may occur at either a grammatical or a narrative level.Footnote 25 At the grandest level, it provides a metaphor for the way in which the mock heroic functions – the narrative trajectory mirrors the protagonist's confused thoughts, leading the reader through various expectations which are never fulfilled. Extended narrative prevention of real heroic deeds causes the reader to question and redefine the nature of the heroic mode itself. As one literary critic describes it, narrative periphrasis in the mock heroic ‘alters perception’ and ‘transmutes thought’:

It takes a trifle and leads large words around it, over and again, in a never-ceasing refusal to name directly … It seizes an unlikely world … in the continuity of its inflationary and circumlocutional language, so as to recreate it in comedy and in a new dimension.Footnote 26

III

In order to perceive the mock-heroic narrative characteristics of L'Anagilda, we must explore the relationship of this work to the epic tradition. Only in comparison to the epic can any work be described as mock heroic, since all forms of comic epic ultimately satirize or parody their serious counterpart in some way. Certain qualities are inherent in the epic: historical characters and events, a peripatetic hero, a series of heroic tasks, difficult conflicts or battles that confront good and evil, and the completion of a grand and noble quest. Without these basic elements a long poem does not qualify as an epic, and without allusion to or distortion of these elements, a comic work does not qualify as a mock epic. In Gigli's L'Anagilda these qualities create an epic frame of reference, but the characters and sequence of events fall short of the heroic plane.

Like earlier writers of mock-heroic works, Gigli bases his libretto on historic events and mixes elements of comedy and fantasy into his plot. As he explains the events that precede and set up the drama in the Introduction to the libretto, Count Fernando and King Sancio had been bitter enemies. After deciding to let fate determine the final outcome of their disagreements, they met on the battlefield one last time. In this battle Sancio was defeated.Footnote 27 When he turns, in the opera itself, to the subsequent amorous intrigues between Count Fernando and Anagilda (daughter of the now deceased King Sancio), Gigli focuses on a small aspect of a real event. Through his narrative and through the language with which the characters speak he inflates trivial actions to disproportionate grandeur. Through parody and satire he deflates heroic ideals to triviality. Although Gigli could have chosen the serious background events he describes in his Introduction (the epic conflict and battle between Fernando and his nemesis King Sancio), he instead chose the love intrigues, which show none of the characters in their best light.

The opera's plot is easily summarized. Fernando's epic quest requires him to travel to the land of his former rival and claim the prize of his newly formed political treaty – marriage to Anagilda, daughter of the deceased King Sancio and sister of the vengeful Garzia. Before he even sets out, Fernando's own sister, Elvira, reveals a deep-seated fear for his safety (Act 1 Scene 1). After this inauspicious beginning, many obstacles block Fernando's path. First Garzia imprisons him to await execution (Act 1 Scene 10). Then Anagilda, after rescuing him from prison, discovers a note written to Fernando by another woman (Act 3 Scene 5); not realizing the letter was from Fernando's own sister, she abandons him, still in chains, in the countryside. Fernando, our hero, unable to act or defend himself, is forcefully confronted with his plight in Act 3 Scene 6.

Fernando is therefore entirely robbed of his motivations for heroic action until Act 3. By the next time we encounter the couple together, in Act 3 Scene 11, we are told that a shepherd has released Fernando from his chains and told the truth to Anagilda. In the meantime they have deduced that Garzia must have imprisoned Elvira (during her own attempt to rescue Fernando), and now Fernando must rescue his sister in order to fulfil an ancient prophecy. Disguised as a warrior, he confronts Garzia in Act 3 Scene 16 to save his sister according to this prophecy. This is Fernando's one heroic act of the opera, but the arrival of Anagilda, also disguised as a warrior, thwarts its realization in the final scene. Anagilda, the only true ‘hero’ of the opera, forces reconciliation between her brother and her new husband. She thus emerges as the ultimate hero of this opera by saving everyone from destruction.

The heroic parody at work throughout the opera can be seen through a close analysis of a few scenes. These scenes will demonstrate certain important elements of the mock heroic: Fernando's demonstration of his supposedly ideal virtue is continually thwarted by the immediate reality that he faces. The resulting ‘disjunction’ between imagination and context leads to his psychological self-imprisonment in his own overly strict yet also antiquated value system, which in turn fuels his madness. Finally, comic events, including the ultimate usurpation of his own gendered role by Elvira and Anagilda, further belittle his own sense of heroism.

Fernando's language reveals his idealized gallantry and romanticized notions. At the outset of the opera Fernando speaks of glory, love, hope, reason, holy laws and heaven. Perhaps the most telling moment occurs when Fernando reveals his blind trust in fate in the very first scene of the opera: ‘And what misfortunes can heaven prepare for me if the beautiful Anagilda is my destiny?’ (‘E quai sventure / Può prepararmi il Cielo / Se la bella Anagilda è il mio destino?’, Act 1 Scene 1). After Fernando has recognized Garzia's deception, his language changes to noble outrage, now promising retribution, justice and death. To Anagilda, he expresses a willingness to die in order to quench her family's thirst for revenge: ‘And even though today you conspire to betray me, Fernando would die for you, most happy that you can accomplish yet another beautiful betrayal’ (‘E se pure a tradirmi oggi congiuri, / Più contento per te Fernando muora, / Che puoi far bello un tradimento ancora.’ Act 1 Scene 9).Footnote 28 This heroic self-sacrifice is, however, thwarted by Anagilda's conscience. In spite of her hatred for Fernando, she will not kill him, for she does not wish to make her unfortunate situation worse through an additional murder.

The extreme incompatibility of Fernando's ideals with his reality leads him towards madness. Fernando's madness initially surfaces in a sort of naiveté and refusal to consider or recognize the reality of his political situation and the danger to his life. His more practical and sensible sister provides a counter example through her warnings. In the strange episode in which he communicates with a statue of the dead King Sancio (Act I Scene 8) one wonders whether he is entirely sane.Footnote 29 Upon seizing Fernando and surrounding him with prison guards, Garzia forces him to confront a statue of the former king. While the statue is meant simply to confront Fernando with the reality of his past actions, Fernando uses the statue as a means of his own redemption. He places his own sword into the statue's grasp and creates a prophecy: if he is guilty of deception, the statue can enact revenge; if not, the statue must render the sword to Fernando's defender:

[recitative] Sancio, I grant you my sword; if I have ever betrayed you, in the name of Justice, if Justice is sacred in heaven, I invite your stone hand to commit vengeance against my heart, but if I am innocent, render this sword to a faithful hand that will defend me.Footnote 30 (Act 1 Scene 8)

Here the statue represents Fernando's blind acceptance of overly narrow concepts of heroism, justice and vengeance. Although Fernando had killed King Sancio, he refuses to understand why he is unwelcome at Garzia's court. He has followed strictly his own precepts. But he also expects the statue itself to exact retribution. These are forms of madness: not only are Fernando's precepts born of irrationality, but now he attributes agency to a stone replica of his former enemy. He relives his conflict with Sancio as though with an animate being, because he cannot face the reality that his previous conflict now has been transferred, through Sancio's death, to both Garzia and Anagilda. In the world of Arcadian verisimilitude and rationalism, the statue represents insanity, lack of reason and improbability.

The use of madness as a literary device resonates particularly well with the tradition of the mock heroic established by Cervantes's Don Quixote. Gigli had even used the character Don ChisciotteFootnote 31 in several of his opera librettos – Lodovico Pio (1687), Amor fra gl'impossibili (1689) and L'Atalipa (c1701) – and also in a non-musical comedy entitled Don Chisciotte, ovvero un pazzo guarisce l'altro (1698). For Gigli, Don Chisciotte is a recurring character, who remains virtually unchanged from one drama to the next: he is metatheatrical, taking on a life of his own outside of each individual drama, constantly reappearing under new circumstances but with similar motivations. In each work, Gigli's Don Chisciotte emulates but consistently falls short of the actions and ideals of Orlando from L'Orlando furioso.Footnote 32

In Lodovico Pio, for example, Gigli uses the contrast between aggrandized ideals and frivolous action to emphasize the alienation from reality that Don Chisciotte suffers. In this opera he places serious heroic speeches from Tasso and Ariosto into the mouth of the comic Don Chisciotte, creating a disparity between the heroic and the ridiculous. The author describes this incongruity in the Preface to the libretto:

Troverete che Don Chisciotte usa tal volta versi presi dal Tasso e dall'Ariosto. Non mi crediate sì temerario che io pretenda mettere in burla due autori da me riveriti e stimati come Maestri della Poesia; ho solamente voluto esprimere i pensieri del Personaggio co' i versi di que' degni Poeti, per far nascere il ridicolo dal contraposto, facendo servire una grande autorità ad una gran follia.Footnote 33

You will find that sometimes Don Chisciotte uses verses taken from Tasso and Ariosto. Do not believe me so bold that I would presume to ridicule two authors revered and esteemed by me as masters of poetry; I only wanted to express the character's thoughts with the verses of those worthy poets to give birth to the ridiculous through its opposite, making a great authority serve great folly.

Don Chisciotte is heroic by reference, but (like the original Don Quixote) suffers from the disparity between his imagination and the reality in which he finds himself. In L'Anagilda, Gigli models Fernando after his earlier character Don Chisciotte, creating a specific situational reference to the previous librettos through plot elements that highlight Fernando's inability to reconcile his ideals with his environment.

Fernando even mocks himself through comic situations that minimize his position as hero. While imprisoned in Act 2 he dwells upon his future reputation as a heroic figure in epic storytelling, though he has as yet committed no heroic act: ‘A fortunate time will come when the horrible fate of Fernando will be remembered’ (‘Verrà un tempo fortunato / In cui forse rammentato / Di Fernando il caso orribile.’ Act 2 Scene 5). Fernando's views of himself are simultaneously self-aggrandizing and self-deprecating; after first marking himself as the hero of a future epic tale, he then continues by marking himself as a victim: ‘It will be said that such fierce cruelty is not possible.’ (‘Si dirà; non è possibile / Così fiera crudeltà.’) Fernando's choice of words also projects future disbelief of the tale (‘non è possibile’); thus he will be memorialized in a future epic narrative, in which he is portrayed as a victim, but the circumstances of his plight will lack credibility. Fernando's language mocks his own heroic self-image.

The sequence of comic events that leads up to Fernando's rescue from Garzia's prison further trivializes his heroic role. Elvira, who has gained access to Garzia's court by disguising herself as a Moor and a magician, first throws a sword into his prison cell. To the sword is attached a note reading ‘Fight and hope’ (‘Combatti e spera’). Fernando does not read the remainder of the note, which would have revealed Elvira's intention to rescue him, but picks up the sword and uses it to injure an intruder, thinking that he is following the directions represented. In fact, he has injured Anagilda, who also has disguised herself to gain entry to the prison and remove Fernando without detection. Throughout the scene, Fernando's language indicates his overblown heroism and romanticism. First, he wants to inflict injury on himself in retribution for the injuries he has inflicted on Anagilda: ‘And you, cruel right hand that has erred so severely, will correct this mistake with the same sword, since my grief alone is not sufficient to punish it’ (‘E tu destra crudel, che tanto errasti / Col ferro istesso emederai l'errore, / Quando a punirlo il mio dolor non basti.’ Act 2 Scene 14). Then, he cannot bear to tread across Anagilda's blood, which has dripped on the floor: ‘Oh, that my devoted foot, so as not to tread upon the blood that drips from such a beautiful hand, may move with uncertain step across the ground’ (‘Ahi che il divoto piede, / Per non calcar quel sangue, / Che dalla bella man stillar si vede, / Nel suol macchiato il dubbio passo muove’). While Fernando delays with his heroic speeches, Anagilda has to remind him no fewer than seven times that they must leave immediately or risk their lives.

This scene accomplishes two things. First, it contributes to the portrayal of Fernando as ridiculous. Through his insistence Fernando becomes incapable of action; he is stuck between his imagined heroic ideals and the reality that he faces, unable to reconcile the two. Second, the scene as a whole directly opposes Arcadian theories of verisimilitude. It mirrors exactly the conflicts that Lodovico Antonio Muratori railed against in Della perfetta poesia italiana of 1706, conflicts between the inner, subjective time of the character's self-expression and the narrative time experienced by the audience in the theatre. As Muratori wrote,

troppo sconcio inverisimile è il voler contraffare, e imitar veri personaggi, e poi interrompere i lor colloqui più seri, e affacendati con simiglianti Ariette, dovendo intanto l'altro Attore starsene ozioso, e mutolo, ascoltando la bella melodia dell'altro, quando la natura della faccenda, e del parlar civile, chiede ch'egli continui il ragionamento preso. E chi vide mai persona, che nel famigliar discorso andasse ripetendo e cantando più volte la medesima parola, il medesimo sentimento, come avvien nelle Ariette? Ma che più ridicola cosa ci è di quel mirar due persone, che fanno un duello cantando? che si preparono alla morte, o piangono qualche fiera disgrazia con una soave, e tranquillissima Arietta? che si fermano tanto tempo a replicar la Musica, e le parole d'una di queste Canzonette, allorché il soggetto porta necessità di partirsi in fretta, e di non perdere tempo in ciarle?Footnote 34

Inverisimilitude is the desire to dress up and imitate real people, and then interrupt their most serious conversations with arias, while the other actor must remain idle and silent, listening to the beautiful melody of the first, even though the nature of the affair, and of civil speech, requires that he continue the argument at hand. And who has ever seen a person repeat himself, singing the same words and sentiment many times during a conversation, as occurs in arias? And what can be more ridiculous than watching two people who sing while duelling? Who prepare themselves for death, or lament some shameful disgrace, with a gentle or calm aria? Who stop to repeat the music and words of a song, when the situation requires a hasty departure, rather than wasting time in idle chatter?

While Muratori complained first and foremost about how the time necessary to perform arias created inverisimilitude within the dramatic context, each of the situations to which he refers also invokes startling stubbornness or idleness when haste is required. In L'Anagilda Fernando's intentional ignorance of his impending peril is not simply imposed on the drama by its musical form but is already inherent in his text, creating an exaggeration that could not fail to impress the audience.

The scene parodies not only Fernando's role as hero, but also subtly the very idea of Arcadian reform. While an Arcadian audience might interpret this scene as an inside joke, an intentionally overblown reference to stock anti-Arcadian elements in order to expose and ridicule them, there is another possible interpretation, for Gigli spent considerable energy lampooning the strict antiquarian programmes of the Cruscanti and even the narrow-minded pastoralism of the Arcadians. As a stubborn literary and political satirist and an extremely independent critic of current linguistic programmes, Gigli must have intended this scene as an intentional condemnation of reform ideas – ideas which it is likely that he interpreted as limiting poetic and dramatic creativity.

Later in the libretto we find the climax of Fernando's recurring frustrations. When we encounter Fernando bound in chains in the countryside, suddenly abandoned by Anagilda, impatient to act but unable to move, we find the epitome of the mock-heroic figure. This scene also shows how Gigli carved the 1711 L'Anagilda out of pre-existing material from the 1689 La fede ne' tradimenti and added new material to heighten Fernando's mock-heroic characterization.Footnote 35 Since this scene furnished Caldara with a weighty new aria, we will also see one example of the way in which Caldara's setting of the opera emphasizes Fernando's plight.

In the 1689 libretto Anagilda hurriedly departs after reading Elvira's letter, which she mistakenly interprets as a love letter from a rival for Fernando's affections (Act 3 Scene 4 in the 1689 version, Act 3 Scene 5 in the 1711 one). Then the scene concludes with three lines of recitative in which Fernando reveals his own discovery that his sister is the author of the letter. In revising the libretto for the 1711 performance, Gigli ends the scene at Anagilda's hasty departure, then creates a new scene with Fernando's recitative, followed by a new aria (‘Catene del piè’):

[aria] Chains, now you are my painful burden. You weigh on me heavily. Help! Mercy! You hold my impatient foot. Break!

This simple change conforms to the modern convention of defining scenes by the entrance or exit of a character, and it provides an additional exit aria for Fernando. Yet through both text and music this new aria also offers one of the most salient examples in the opera of Fernando's conflict between inward expression of heroism and outward physical incapacity.

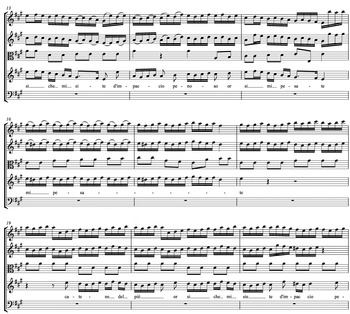

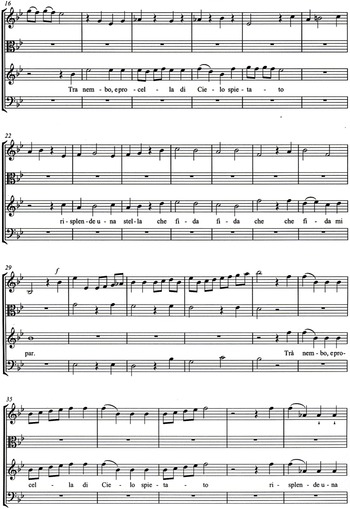

Caldara's setting of this text reveals Fernando's hurried frustration (see Example 1).Footnote 36 By creating a vocal display of bravura, Caldara emphasizes the distinct disparity between Fernando's emotions and their expression, between his intentions and his actions, or lack thereof. Caldara also emphasizes Fernando's inability to fulfil his heroic role; the headlong rushing of the aria setting clashes with his immobility. While Fernando remains musically heroic in the face of his adversity, his physical imprisonment prevents him from accomplishing his designated part in the drama. Both librettist and composer thus satirize the role of the hero. Through his text Gigli creates a pathetic figure, robbed of his heroic stature. Through his music Caldara taunts Fernando with the action that he is unable to accomplish.

Example 1

‘Catene nel piè’, bars 10–21, L'Anagilda, Act 3 Scene 6 (all examples are my transcriptions from the Diözesanbibliothek (Münster) manuscript SANT Hs 801 I.II.III., and are used by permission)

Measured against the heroic standards of serious epic literature, Gigli's Fernando consistently falls short of the mark. Yet those standards are apparent even as they are negated. Fernando is peripatetic, first setting out on his amorous conquest, then escaping from prison through the agency of Anagilda and wandering with her in the pastoral wilderness and, finally, returning to avenge and rescue his sister Elvira. Yet only in the first and last of these instances does Fernando act of his own accord, and in the last his action is thwarted by Anagilda's intervention.

Fernando also faces serious conflicts and moral challenges, but he never solves any of these. The contrast between his language and his actions creates a tragicomic effect; the disparity between his inner bravura and his outward immobility is a parody of his own heroism. It is true that the prehistory to the opera would define him as heroic – he had challenged his rival to a duel and emerged victorious – but his behaviour in the opera itself quickly belies any expectations.

Finally, it is perhaps this opera's use of incongruity and narrative periphrasis, the constant frustration and subversion of Fernando's heroic actions and the masculinization of the two female characters (which resonates with Gigli's discussion of Tuscan language in the Vocabolario Cateriniano) that strike at the core defining elements of the work in its adherence to mock-heroic principles. Whereas Gigli complains of the grammatical changes in gender espoused by the Accademia della Crusca, in L'Anagilda he uses gender subversion to criticize the Arcadian concept of the hero. In both instances, Gigli uses the example of gender to attack narrow and rigid reform agendas and to question the academies' methods for determining linguistic and literary correctness. Gigli's original title for the 1689 libretto, La fede ne' tradimenti (Faith among Betrayals), which became the subtitle of the 1711 libretto, further highlights the paradoxical nature of his opera: only Anagilda's firm faith in the face of the deceptive machinations of her brother and the perceived deceptions of Fernando allows her to save herself from the ultimate despair of losing either her brother or her husband.

IV

So what was Gigli's aim in his use of the mock heroic in L'Anagilda? I contend the following: 1) Gigli created his own brand of controversial neoclassicism, using the same retrospective, classical methods as the Arcadians but intentionally focusing on genres and sources not embraced by their aesthetic ideals; 2) Gigli turned his own form of neoclassicism into an alternative path towards Arcadian aesthetic goals through the mock heroic; and 3) such a parody was motivated equally by the contentious events surrounding the Arcadian schism in 1711 – the same year as the opera's performance in Ruspoli's bosco Parrasio – and by Gigli's own career-long personal taste for satire.

In spite of Arcadian condescension towards the genre, the mock heroic bears a literary history parallel to other forms favoured by the group. The mock-heroic genre, although opposed by the strict neoclassicists of the Arcadian Academy, does in fact have classical roots. As a mode it was used by many ancient Roman satirists, Ennius, Lucilius, Horace and Juvenal among them.Footnote 37 Other satirical and parodistic modes also have classical origins in Menippus and Lucian and were further imitated in the Italian Renaissance by authors such as Pietro Aretino.

Although Gigli may not have subscribed to the exact brand of neoclassicism promoted by the Arcadian Academy, his works often have their own classical genealogy. Gigli's interest in Pier Jacopo Martello's Il piato dell'H as an appendix to his own Vocabolario Cateriniano provides one example of the classicist traces of both authors' uses of satirical genres.Footnote 38 Martello's Il piato dell'H is modelled on a satirical work by Lucian in which one letter (sigma) draws up a court proceeding against another letter (tau) for having stolen all of his words.Footnote 39 Martello's work is a perfect companion for Gigli's polemical arguments against the linguistic censorship of the Accademia della Crusca. Furthermore, as Gigli notes in the Vocabolario, Martello's imitation of Lucian occurs indirectly, by using a French author as a model.Footnote 40 This is the same process by which many Arcadians imitated Greek tragedy, using as models intermediary works by French authors, such as Corneille and Racine, who were themselves imitating classical tragedy. It seems particularly ironic that Gigli's polemical and satirical writings on issues pertaining to the imitation of classic authors should have been the impetus for his expulsion from the literary academies charged with institutionalizing and preserving Italian language and literature according to Italy's classical Greek and Latin heritage.

Gigli's criticisms of literary reform in his Vocabolario Cateriniano were not restricted to the Accademia della Crusca, but extended also to the Arcadians. Under the entry for ‘Presta’, he includes a jab at the pastoral metaphors used by the Arcadians:

non trovandosi nel bosco parrasio un leccio, o un frassino intaccato per segno di confine delle ragioni di un Pastore; ma solo lecci intaccati di versi amorosi d'Irene, di Fidalma, e d'Aglauro. Ne meno veggonsi fosse divisorie, ma solo fosse … per lo scolo delle piogge, e del fonte Aganippe, ai ritorni del quale si abbeverano le gregge virtuose, che belano in metro particolare, e belano in rima, a differenza delle pecore ignoranti degli altri paesi, che belano senza badare alle sillabe, ne ad alcuna poetica armonia.Footnote 41

nowhere in the bosco Parrasio is there an oak or an ash engraved to show the bounds of a[n Arcadian] shepherd's reasoning, but only oaks notched with the amorous verses of Irene, of Fidalma and of Aglauro. Nor are there to be seen any dividing gullies … but only ditches for draining the rains and the spring Aganippe, at whose sources the virtuous herds drink, who bleat in distinct metre and in verse, unlike the ignorant sheep of other countries, which bleat without paying attention to the syllables or to any poetic harmony.

If one considers Gigli's tendencies towards nonconformism with respect to current literary trends, his subversive attitude towards strict literary reform programmes and his individualistic interest in the classical heritage, one does not have to look far for a motive in his use of the mock heroic in L'Anagilda. In using the mock heroic, subverting the values of classic epic poetry, Gigli ultimately blasphemes the literary practices for which the Arcadian Academy stands. L'Anagilda is, therefore, an intentional literary parody of Arcadian reform.

This parody, however, is not random, but is rather systematically applied according to the fundamental symbolism inherent in Arcadian iconography. In classical literature Arcadia is often represented as a paradoxical realm. On the one hand, it represents the goodness and bounty of pastoral otium, a safe haven for the realm of the natural. On the other hand, it is also a place where danger lurks, where the potential for destruction casts its shadow. One need only look to Ovid's Metamorphoses to discover pastoral images that quickly disintegrate into tales of ruin and pathos. Or to the first poem of Vergil's Eclogues, to discover that the pastoral goodness bestowed upon Tityrus derives from Meliboeus's reversal of fortune.Footnote 42 Or to Tasso's Aminta, a seminal work for the emulation of Arcadian pastoral values, to discover the devastating near rape of the nymph Silvia in a landscape that replicates the simplicity and goodness of the Golden Age. The art historian Vernon Hyde Minor recognizes similar paradoxical iconographies in the architecture of the bosco Parrasio, the official Arcadian garden on the Janiculum hill in Rome. As he writes:

the garden and the Arcadian experience were – in ways that strike one as antithetical to Muratori's philosophizing about good taste – caught up in dissimulation, suppression, obfuscation, reticence, and – at times – deceit. The ragione del gusto could, in its application, be irragionevole.Footnote 43

Gigli's message in using the mock heroic is to emphasize both the hypocrisy of the overly narrow definition of classicism within the Arcadian reform programme and the incongruous nature of emulating pastoral values in order to represent heroic virtù.

Gigli was not the only person in 1711 to use the mock heroic to criticize members of the Arcadian Academy. In this year of the Arcadian schism, a follower of Gravina wrote Il Giammario, ovvero l'arcadia liberata, which lampooned Crescimbeni. By 1711 satire as a form of debate and protest already had a long history within the group. In 1696, despite the prohibitions against satire published in the leges Arcadum in that very year, Lodovico Sergardi collected together a series of satirical attacks against Gravina titled Satyrae. Begun as early as 1692–1694,Footnote 44 these poems were a direct response to Gravina's own attacks against the Jesuits in the Hydra mystica (1691). In addition, the Arcadian caricaturist Pier Leone Ghezzi used visual satire to lampoon his subjects, while Martello, colleague and friend to Gigli, was a career satirist who none the less maintained a secure place within the Arcadian Academy.

V

Despite L'Anagilda's inherent unconventionalities, many elements of the revised 1711 libretto and score create greater levels of verisimilitude than the original seventeenth-century version of the opera. However, Gigli does not achieve such verisimilitude by such traditional neoclassical methods as the elimination of comic scenes and distracting subplots, or the streamlining of the drama by the deletion of arias and the greater reliance on recitative for narrative delivery. Instead, Gigli adds new arias and even whole scenes, not to mention the two new comic characters and several intermezzos. By creating a new depth and consistency of characterization, Gigli's work tells the Arcadians that there is more than one path towards accomplishing their dramatic goals.

A comparison of the original 1689 libretto with the revised 1711 version will demonstrate Gigli's tactics, and an analysis of the music created for the new material by Caldara will demonstrate how the opera in its complete form enhanced the drama's verisimilitude and perhaps even softened its paradox.

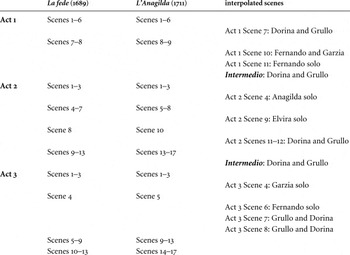

Surprisingly, although separated from the original La fede ne' tradimenti by twenty-two years, L'Anagilda's seventeenth-century roots are clear. Little of the libretto's original fabric has been altered to create the 1711 adaptation set by Caldara. Rather, as one can see in Table 1, the principal large-scale structural modifications are the insertions of new scenes. Besides the intermezzos and interludes added for the new comic characters Dorina and Grullo, Gigli also interpolates six new scenes for the primary characters.

Table 1 Structural comparison of La fede ne' tradimenti (1689) and L'Anagilda (1711)

Although the basic structure of the 1689 opera still exists within the 1711 version, Gigli has made many smaller-scale revisions within the individual scenes to modernize the drama. In the scenes taken from La fede ne' tradimenti Gigli has deleted twelve arias. Of these, four occur at the beginning of a scene, eight occur in the middle of a scene, and none are exit arias. (See Table 2.) Gigli also strategically deleted recitative passages at the end of two scenes in order to create exit arias out of mid-scene arias in Act 1 Scene 4 and Act 1 Scene 6. In addition, he marked many passages in the 1711 text with virgole to indicate cuts that could be made to shorten the opera.Footnote 45 These passages were not set by Caldara in his score. Through these additional, optional deletions, he allowed for the potential elimination of eight more opening and mid-scene arias (see Table 3). Finally, Gigli added nine new exit arias (Table 4). These revisions demonstrate an inclination towards exit arias, as became common in the eighteenth century, at the expense of entrance and mid-scene arias. On the one hand, pushing the aria to the end of the scene allows the narrative to proceed with less interruption and satisfies one of the structural requirements of Arcadian verisimilitude. On the other hand, exit arias also satisfy the audience's demand for theatricality. Hence, a delicate balance had to be maintained, as was noted by Gigli's satirical colleague Martello in his humorous description of impresarios, composers, librettists and singers in his Della tragedia antica e moderna (1714):

Entrance arias are sung when a character comes on stage, and are particularly suited to soliloquies … However, you are to make use of them sparingly. The mid-scene arias should be used with equal parsimony, as they have a lifeless effect each time singers who are silent are obliged to remain standing in the middle of a scene while listening to someone else singing unhurriedly … The exit arias must close each scene, and a singer ought never leave the stage without an ornamented canzonetta. Whether or not this accords with verisimilitude is of little importance, as hearing a scene ended spiritedly and with liveliness is all too exciting.Footnote 46

Despite his humour and satire, Martello leaves it clear that mid-scene arias imposed too much on dramatic continuity, while the lack of verisimilitude in exit arias could be excused. Martello, like Gigli, also comments on the conflict between Arcadian theory and practice.

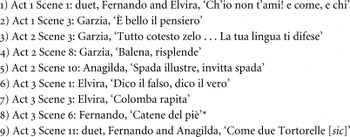

Table 2 Arias deleted from La fede ne' tradimenti (1689) to create L'Anagilda (1711)

Table 3 Arias marked for deletion in L'Anagilda (not set to music by Caldara)

* Since eight preceding lines of recitative, which in turn are preceded by another aria, are also deleted, the scene still ends with an exit aria, Garzia's ‘Caro sì, ma non venne dal core’. Thus, even though an exit aria is deleted, another takes its place.

Table 4 New exit arias added for L'Anagilda in 1711

* This entire scene is newly added to the 1711 libretto; see Table 1 above.

In addition to providing new opportunities for solo arias, Gigli's new scenes for L'Anagilda expand the characters' personalities. I will first examine the two new scenes that close Act 1, which provide definitive characterizations of the main players in the drama. The first, Act 1 Scene 10, occurs after Garzia's deceitful imprisonment of Fernando. After Anagilda exits, having answered Fernando's prayer to Sancio's statue in the previous scene, Garzia and Fernando remain on stage. Fernando requests an immediate end to his own suffering, but Garzia reveals his cruelty in a passage that expresses his torturous bloodthirstiness:

[recitative] No, you will die when I am satisfied. [aria] I have long thirsted for your death in my heart. I intend to extend your torment for my own delight and to drink, drop by drop, your tears and your blood as it pours from your veins.

This gruesome text shows the full extent of Garzia's brutality, which in turn creates a more striking contrast with his subsequent amorous feelings for Elvira. In the 1689 libretto, which lacks this number, Garzia is deceptive and vengeful but not so malicious.

Immediately following this scene, after Garzia's departure, Fernando remains alone to ponder his fate and the possibility that Anagilda might experience a change of heart:

[recitative] Sancio, father more just and compassionate than your fierce offspring, shorten the span of my painful life, I pray: ah no, you armed Anagilda with my sword, and you intend her to be the beautiful Astraea of my innocence. [aria] Amid the hail and tempest of a pitiless Heaven a faithful star seems to shine. Even she radiates wrath, although it seems that she wishes to calm her fury.

This passage, in spite of the stock text in the A section of the aria, creates a more sympathetic, compassionate character. Fernando is given the opportunity to reveal his respect for Sancio and his regret for his warring past. Furthermore, he reinforces the foreshadowing of Anagilda's ensuing sympathy towards him in Act 2.

These two new scenes, together with the new exit aria for Anagilda added at the end of Act 1 Scene 9, provide a less abrupt ending to the act. In Gigli's conclusion to Act 1, three of the four characters show their thoughts through their exit arias: Anagilda's ambivalence towards Fernando (Act 1 Scene 9, ‘Cara man del Padre esangue’), Garzia's brutality (Act 1 Scene 10, ‘Lunga sete ebbi nel petto’) and Fernando's hope for pity (Act 1 Scene 11, ‘Tra nembo e procella’). Although these additional arias do not enhance the dramatic logic of the narrative per se, as we might reasonably expect from revisions made for an Arcadian production, they do help round out the characters' personalities and provide a broader perspective for interpreting their forthcoming actions and interactions on stage. Overall, these changes create a chiaroscuro effect that enhances the contrast between the characters' emotional states at the beginning and conclusion of the opera and also creates a more striking denouement. Gravina endorsed such methods in his 1691 Discorso sopra L'Endimione, a work which outlines the myriad facets of verisimilitude, when he praised an author's use of surprise when brought about by a character's unexpected change of heart.Footnote 47 Interestingly, Fernando's character is the only one in Gigli's libretto that never changes; his stasis indicates that he is not heroic and minimizes his effect on the drama's unfolding.

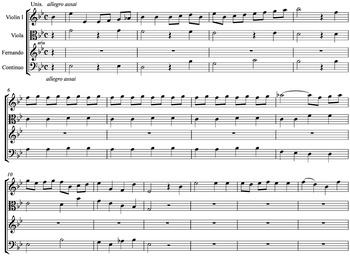

Example 2

‘Cara man del Padre esangue’, bars 1–24, L'Anagilda, Act 1 Scene 9

The music for these new scenes illustrates the greater depth that they add to the drama and establishes a musical closure that complements Gigli's new dramatic scheme. The arias further define and identify the personalities and motivations of the characters, which in turn clarify the dramatic narrative by explaining, in musical terms, the basis for their future actions on stage. We will look at the music of these new arias for the two main characters, Anagilda and Fernando.

Caldara's setting of Anagilda's aria ‘Cara man’ exemplifies the duality of her emotional state (see Example 2). The orchestral introduction reflects her anger at Fernando, while her initial vocal entrance mirrors the pain of her father's demise. The contrasting adagio and presto tempos in the vocal line accentuate her conflicting emotions. The extensive and vocally demanding melismas that first appear in bars 12–14 and return later in bars 20–22 and after bar 27 particularly highlight her anger. These vocal outbursts grow out of the orchestral introduction, where the motive first appears in the violin in bars 2–3. It continues to be echoed in the orchestra, punctuating and providing contrast to the more lyrical aspects of the vocal line. Furthermore, Anagilda's emotional struggle in the A section parallels her conflicting feelings for Fernando exposed in the B section:

[aria] Beloved hand of my lifeless father, give me strength for vengeance. While I grasp this sword two emotions hold me at bay: one desire that seeks blood, one desire that cries, ‘wait’.

This contrast between Anagilda's anguish and her pleas for the strength and capacity to enact revenge, as depicted in both text and music, creates a character that is complex and multi-faceted, whose conscience ultimately determines her future heroic course of action. Anagilda's temperament seems more realistic and human in her weakness and turmoil. Unlike Fernando, she is able to defeat her primary flaw – indecision – by following the path of honesty and clemency. Her dilemma therefore becomes more personal, humane and genuine, and her role in the drama is augmented with respect to that of Fernando.Footnote 48

The final new aria of Act 1, ‘Tra nembo e procella’, highlights Fernando's predicament, especially the characteristic sense of imprisonment and helplessness discussed above, by textually and musically representing his emotional turmoil and his physical helplessness. The musical affect derives from the hail and thunderstorms mentioned in the text rather than from the shining star embodied by Anagilda (see Example 3). By concluding the act with a musical representation of Fernando's stormy frustration, Caldara defines the primary subject matter of the opera: the stereotypical ‘hero’ is powerless to fight against the obstacles that beset him. The sparse accompaniment to the vocal line, consisting only of the violins either in thirds or in unison, further illustrates his helplessness: he cannot muster the full support of the orchestra to punctuate his rage. Instead of raining down his vengeance on his opponent, as in the typical rage aria, he must be content with expressing this emotion in his physical and psychological imprisonment. His supposed role is subverted and granted instead to the prima donna.

Example 3

‘Tra nembo e procella’, bars 1–39, L'Anagilda, Act 1 Scene 11

VI

Although L'Anagilda may not provoke today, it did in its own time, as did many of the works produced by Gigli. He had a penchant for satire throughout his career and was ever controversial. For example, when La fede ne' tradimenti was performed in Milan in 1700, though with extensive cuts and a less controversial title (L'innocenza difesa), it was terminated because of its patron's religious objections.Footnote 49 Gigli persistently mocked influential persons who exhibited characteristics that he disliked (hypocrisy, bigotry and prejudice) and often confronted censorship in various guises – the Florentine Inquisition under the rule of Cosimo III de' Medici, the narrow linguistic precepts of the Accademia della Crusca, and the Jesuits, for whom Gigli wrote many librettos at the Collegio Tolomei in Siena – all of whom only succeeded in inflaming further his attacks against them. Gigli therefore not only amused his audience with his wit and satire but also intended to push what he perceived as severe limitations on artistic expression. Indeed, many of his most popular works were also his most controversial, and he suffered greatly from the harsh judgments and censorship of his critics.Footnote 50

Gigli's acts of satire were not limited to published works. When he acted in his own Il Don Pilone he played the role of the main character, a hypocrite, and in his portrayal impersonated a well-known Jesuit priest, Father Feliciati (who was later imprisoned by the Sienese Inquisition for corruption in 1714). In spite of audience acclaim for the first two productions (1707 and 1709), the Jesuits applied to Cosimo III to revoke Gigli's position at the University of Siena and to prevent the play's publication (which did not occur until 1711). As a result, Gigli was forced to move to Rome. Much of the most damaging material in Don Pilone never appeared in the published version but was depicted graphically on stage, and can only be surmised based on eyewitness accounts. Most of the material involved insinuations that the Jesuits were in partnership with the devil and participated in sexually explicit acts.

After returning to Siena in 1712, Gigli further provoked his attackers by writing the sequel to Don Pilone. It was entitled La sorellina di Don Pilone o sia l'Avarizia più onorata nella serva che nella padrona and was published forthwith in 1712. In a companion skit done during Carnival – a sort of ‘performance art’ piece – Gigli dressed up as Don Pilone, sat in a papal chair and, hiding his face, used tongs to distribute a witty madrigal text to the ladies in the crowd. The skit referred to a scene from La sorellina di Don Pilone in which a servant bathes her master using tongs, all the while averting her face. In the case of La sorellina di Don Pilone, the subject of Gigli's criticism was not the Jesuits, but severe avarice, as exemplified and personified by his own wife, Laurenzia Perfetti. Gigli maligned her in writing in two satirical sonnets and in the Vocabolario Cateriniano, among other texts. The Preface to La sorellina di Don Pilone was so damaging in its characterization of his wife that her family sought the assistance of Salvatore Tonci, the head of the Accademia de' Rozzi, which had originally supported the play. They succeeded in having the play banned from both performance and publication. In retribution, Gigli later published his satirical novel Il Collegio Petroniano delle balie latine under Tonci's name (manuscript 1717, published 1719).

In several works Gigli clothed fantastical events in the illusion of reality to create political satire. Il gazzettino is a novel comprising a series of fantastic and surreal travel letters written in Rome and sent to several friends in Siena, including a Dominican priest. Although this work circulated only in manuscript during Gigli's lifetime, it was later published in Milan in 1861. Among the real people satirized were Cosimo III, his ambassador to the Holy See (Count Fede), Crescimbeni and Antonio Magliabecchi. The topics included false piety, hypocritical conversion of people in the New World, linguistic elitism and trivial academic topics discussed ad nauseam but with full seriousness and in overblown language, much as one finds in the mock heroic. All of the episodes are framed by the main event, the arrival in Tuscany of Amazonian ambassadors from the court of the Chinese emperor. By referring to real people in the letters and imitating the popular genre of travel diaries, Gigli not only added credibility to the narrative but also personalized the underlying attacks, drawing even more animosity upon himself (though Pope Clement XI was said to have enjoyed the novel). Il gazzettino, like L'Anagilda, satirizes a very real literary genre.

Gigli's exaggeration extended to portrayals of religion and education in the Collegio Petroniano (manuscript 1717, published 1719), which is an extreme satire of Gigli's former employer, the Collegio Tolomei. Under the pretense of announcing a new school in which children would attain perfect Latin literacy thanks to Sienese wet nurses who spoke the language fluently, this work parodies Jesuit education, portraying the Jesuits as ignorant in Latin and Greek, thus necessitating a hospital for injured grammar. To top it off, Gigli's fictitious school was the result of a three-hundred-year delay of the realization of a real cardinal's will (Cardinal Petroni) because of Jesuit mismanagement of funds. Supposedly the hoax was so believable that foreign tourists arrived in Siena to visit the imaginary school.

Gigli used experimental techniques in his stage works, including using several stock characters which reappear across multiple operas as metatheatrical figures. They interrupt the drama to make extraneous comments and often represent Gigli's own political views or rail against censorship. For example,Squotemondo, who appears in La Geneviefa (1685) and La forza del sangue e della pietà (1686), comments that Gigli must be mad for attempting to compose opera librettos for the Jesuits.Footnote 51 Similar characters are Amaranto (one of Gigli's own academic pseudonyms) and Don Chisciotte, discussed above. If characters such as these insert Gigli's own voice into his dramas, then we must wonder in what manner Fernando represents Gigli's criticisms of the Arcadian Academy. If Fernando emulates Cervantes's Don Quixote, whose madness results from the way the heroic ideal continually eludes him, he also represents the reincarnation of Gigli's Don Chisciotte, whose discrepancy between his words and actions emphasizes his own ridiculousness. The combination of Don Quixote and Don Chisciotte within Fernando creates a subtle critique of the Academy: just as Fernando portrays himself as an unheroic hero, he serves as a metaphor for a literary critic unable to enact reform principles in his own poetry and for an academic society crippled by its own idealism.

Gigli's imaginative unconventionality extended even to the authors he chose to emulate. He consistently used literary sources, including Boccaccio, Molière and Cervantes, whose comedic impulses were considered inappropriate and immoral by many contemporaries. To provide just one example, Muratori believed that the works of both Boccaccio and Molière espoused irreverent principles and were thus dangerous to public and civic morality. Beyond such general comments on both authors, Muratori also considered Molière flawed because he ignored the precepts of Aristotle, striving only to please his audience but not to follow the time-honoured, lofty traditions of the classical canon. In Muratori's view the purpose of comedy was to ridicule vices, thereby demonstrating social decorum and propriety through negative examples. Molière, he believed, encouraged such vices and a libertinism contrary to the Gospel texts.Footnote 52 Gigli's use of these kinds of materials in many of his works amounts to a literary rebellion comparable to that found in the Vocabolario and, as I have argued in this essay, in L'Anagilda.

Gigli's innovations ultimately led to his demise. His scathing criticisms of the Accademia della Crusca's strict linguistic programme in his Vocabolario Cateriniano of 1717 proved to be the last straw for his foes. Gigli apparently had worn out his welcome at every institution with which he had been associated, and even his powerful acquaintances and protectors were powerless to mitigate the backlash. Retribution happened swiftly: the Academy asked its patron, Cosimo III, to exile Gigli from Siena, and Cosimo complied. Cosimo, in turn, pressed Pope Clement XI, an ally of Gigli's who had enjoyed the earlier Gazzettino, to exile him from Rome. The pope complied on 19 August 1717. During this same period, Gigli refused the title of Cesarean poet at the Viennese court, a position later held by Zeno and Metastasio, in spite of the fact that it would have provided a solution to his situation.Footnote 53 His Vocabolario was prohibited in Rome (21 August) and in Florence (1 September), where it was burned publicly by order of the Florentine Inquisition, and he was expelled from the Crusca (2 September). Later he was also expelled from the Arcadian Academy.Footnote 54 All of this happened within a few short weeks in 1717. Gigli retreated to Viterbo, where he concentrated his efforts on writing retractions and trying to revoke his exile so he could return to his beloved Siena.Footnote 55 He was finally allowed to return to Rome in 1718 and to Siena in 1721. One work in a career devoted to controversial literary and political satire, L'Anagilda embodies a smaller and perhaps less controversial step on Gigli's path towards political banishment.

L'Anagilda teaches us many things about Arcadia and its reform programme, and provides a broader conception of the group's artistic creations. Gigli's satire not only showed the Arcadians that there were multiple paths to their own goals – to instill good taste while promoting Italian literature and to unite a fragmented Italy into one ‘Republic of Letters’ – but also demonstrates to modern scholars of music that the Arcadians were a more diverse group than has been acknowledged. Gigli recognized the hypocritical nature of the Arcadian agenda and that tragedy was not the only kind of classical drama; by combining alternative classical sources with modern Spanish and French influences and by experimenting with new modes and techniques of expression, he pushed the limits of theatrical representation. Although this case study has been narrowly defined, focusing on one librettist, one composer and one opera, it is my hope that it will revitalize interest in the musical repertory associated with the Arcadian Academy and stimulate new analytical methods for exploring it.

While much attention has been given to the mock heroic in the literary world of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, more needs to be done with this genre in operatic contexts. Similarly, while there has been much focus on the structural aspects of the reform libretto, Gigli's creative revisions, in concert with Caldara's setting, show that modern scholarship has really only scratched the surface of the possibilities regarding Arcadian opera. Some recent work has been done on gender and neo-Platonism within Arcadia,Footnote 56 but much more research is needed to set Arcadian aesthetics within its broader intellectual, literary and cultural contexts.

Although scholars have focused primarily on tragedy and the pastoral in Arcadia, satire was not dead. On the contrary, satire was used to voice dissent, provide constructive criticism and air grievances. L'Anagilda helps us to see that perhaps Arcadia was not as perfectly utopian as its pastoral Golden Age symbolism would lead us to believe. The democratic principles established by the leges Arcadum, which at least in theory provided for the equality of all members, regardless of class, gender or status in the church hierarchy, also left a tacit opening for the creative voicing of alternative opinions.

If the classical pastoral paradigm itself was cracked, allowing for conflict, disjunction, displacement and horror, then why not also the Arcadia of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries? A genre such as the mock heroic mirrors the tensions within Arcadia as the principal players hurled themselves towards the famous fracturing of the group. What better way to comment on literary reform than to hold up a mirror reflecting its internal inconsistencies? Gigli's penchant for amusement and entertainment highlights another inherent problem: how to follow the strict designs of the literary theorists while still providing viable performances. By striking a delicate balance between subversion, humour, satire, commentary and a novel form of verisimilitude, Gigli and Caldara turn erudition into comedy, performance into critique and artifice into art.