These verses are part of El fandango de candil (The Candle-Lit Dance Party), a sainete by Ramón de la Cruz (1731–1794) that had its premiere in Madrid in 1768.Footnote 2 Music and dance are central to the plot: the minuet characterizes petimetres (followers of French fashion belonging to middle and upper social strata), while seguidillas and fandangos characterize majos or manolos (members of the ‘underclass’).Footnote 3 In this work, up to twenty-three characters get together in a clandestine party held in a private house in the Lavapiés neighbourhood of Madrid, one of the (then) peripheral areas where majos lived.Footnote 4 Finally, the local authorities break up the gathering, but until they do, moral and social order is subverted in several ways: there is the mixing of members of different social classes, the dancing of folkloric Spanish tunes considered lascivious at the time (such as seguidillas and fandangos) and the enabling of courtship among strangers (such as the young petimetres who dance a minuet together).

El fandango de candil belongs to a long-standing tradition of Spanish comic theatre in which both popular bailes and highbrow danzas Footnote 5 – together with the musical and poetical topics associated with each of them – are employed as markers of identity that signify specific social classes, nationalities and cultural trends.Footnote 6 In this context, the dichotomy of fandango vs minuet is consistently aligned with majo vs petimetre, and to Spanish tradition vs French fashion. In the case of this sainete, musical instruments are also involved in such games of contrasting binaries. In the beginning, the character Conchitas proudly announces, ‘The dance parties held at my cousin's place are famous; they have at least guitar, violin and bandurria, and the room is full of seats’ (‘Es que son bailes de fama los de casa de mi prima: lo menos tienen guitarra, violín, bandurria y toda llena de asientos la sala’).Footnote 7 All three instruments were typically employed for playing dance music in eighteenth-century Spain, but it seems that not all of them were considered equally appropriate for all types of repertory. When the petimetres dance a minuet, it is the violinist Cuchara (‘Spoon’) who is asked to perform, but when the guests wish to dance seguidillas they call on the guitarist Manolo.Footnote 8 Not by chance, the latter's name is not only a standard version of the forename Manuel but also a synonym for majo; in fact, the association of majos with the guitar is commonplace in short theatre works from the second half of the century.Footnote 9 Thus in this sainete the opposition between Spanish tradition and French fashion also seems to be equated with that between guitar and violin.

While satirical theatre tends toward exaggeration in its plots and expression, the association of the violin with pan-European musical trends in this particular work suggests a realistic reflection of its connections to musical cosmopolitanism and modernity. In fact, in the first half of the eighteenth century Madrid witnessed the assimilation of two repertories that expanded the idiomatic vocabulary and functions of the violin dramatically: Italian sonatas and French courtly dances. The composition and performance of solo violin music that followed pan-European trends increased steadily in royal and aristocratic courts, resulting in a relatively high number of printed publications from 1750 onwards. Moreover, the great popularity of the violin stimulated the expansion of the local music market and the exchange of violin music between Madrid and other European capitals.Footnote 10 One may therefore ask: would it have been shocking for Ramón de la Cruz's audience to see a violinist, rather than a guitarist, perform seguidillas or fandangos? Or would it just have been less effective in dramatic terms?

These questions are connected to broader ones regarding not only the functions of the violin in Madrid's musical life, but also the shaping of a ‘Spanish’ musical identity in the second half of the eighteenth century. As is well known, that period witnessed the rise of majismo or casticismo, an aristocratic fashion for imitating the costumes, manners, music and dance of Madrid's underclass. By the 1770s it had been taken up by such painters as Francisco de Goya y Lucientes and Ramón Bayeu y Subías,Footnote 11 by noblewomen who were influential in setting fashion, such as the thirteenth Duchess of Alba (famously portrayed by Goya in maja costume),Footnote 12 and by satirical writers who lampooned French music and dance, including Juan Fernández de Rojas and Juan Antonio de Iza Zamácola.Footnote 13 Historiography has interpreted majismo as a reaction against foreign cultural trends, especially French.Footnote 14 The same opposition is represented through specific characters in the tonadillas from the last third of the eighteenth century.Footnote 15 In the amateur-music market, casticismo resulted in a great increase in the popularity of guitar playing, and the instrument became an unequivocal symbol of national identity.Footnote 16 Between roughly 1770 and 1810, there was a large market in Madrid for chamber compositions based on folkloric music, especially tiranas, seguidillas, boleros and fandangos.Footnote 17

Foreign visitors to Spain were fascinated by this music, and especially by the fandango; they regarded it as the epitome of Spanish cultural identity, which was purportedly passionate and irrational. In travel diaries, correspondence and literary works, the dance is described as lascivious and the music as exotic – that is, non-European.Footnote 18 Well-known accounts include those by James Harris Jr, Giacomo Casanova, Richard Twiss and Pierre-Augustin de Beaumarchais.Footnote 19 Examples of theatrical and operatic works that make use of the fandango include Don Juan by Gluck (1761), Beaumarchais's play La folle journée, ou le mariage de Figaro (1778), and the opera based on that play, Da Ponte and Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro (1786).Footnote 20 There is no doubt that the fandango played a central role in the shaping of musical ‘Spanishness’.

Paradoxically, this dance-song type, emerging around the turn of the eighteenth century, was probably the result of a complex process of hybridization involving not only Iberian elements but also Latin American (and possibly African American) ones. In 1732 the Real Academia Española published the earliest known definition:

Fandango. [1] Baile introducido por los que han estado en los Reinos de las Indias, que se hace al son de un tañido mui alegre y festivo. [2] Por ampliacion se toma por qualquiera funcion de banquete, festejo u holgura à que concurren muchas personas.Footnote 21

Fandango. [1] A dance introduced [to Spain] by those who have been in the kingdoms of the Indies, which is performed to very joyful and festive strumming. [2] In a broader sense, it is understood as any banquet, party or leisure activity attended by many people.

It seems no coincidence that one of the earliest Iberian sources of this music contains a ‘Fandango Indiano’ (Fandango from the [West] Indies).Footnote 22 A plausible theory is that it arrived from the American colonies via the ports of Seville and Cádiz, and once in Andalusia was hybridized with pre-existing musical schemata (such as the jácara, which features a similar harmonic and rhythmic structure).Footnote 23 In 1712 the clergyman Manuel Martí Zaragoza described ‘a dance of Cádiz, which has always been known for its obscenity’: this was probably the fandango.Footnote 24 Over the following decades the dance spread throughout the Iberian Peninsula, to reach a climax of popularity in the second half of the eighteenth century. Nowadays, after over three hundred years of dissemination and transformation, ‘fandango’ is not a single, clearly defined phenomenon, but an umbrella term that refers to a remarkably wide set of musical patterns and dance types in specific social settings.Footnote 25 In part, this is a result of the metonymic relationship between specific social gatherings and the music performed in them,Footnote 26 as already pointed out in the 1732 definition.

To date, scholarship on eighteenth-century instrumental fandangos has focused mainly on the repertory for solo plucked instruments, keyboard and string quintet. Examples include the well-known stylized fandangos attributed to Santiago de Murcia (c1732), Domenico Scarlatti (before 1757), Antonio Soler (before 1783) and Luigi Boccherini (1771, 1788 and 1798).Footnote 27 By way of contrast, the role of solo violin music in the dissemination of this musical pattern and, more broadly, in the shaping of a supposedly ‘Spanish’ musical identity has been overlooked. This article aims to address this lacuna by analysing and putting into context eight different violin fandangos from the period c1731–1775: these are mostly anonymous and include previously unknown pieces. Some of them were conceived as functional dance music, while others were clearly intended as chamber music. As will be shown, this particular musical pattern was mixed with pan-European trends in instrumental music throughout the violin repertory, and such a mixture challenges traditional discourses on the exoticism of eighteenth-century ‘Spanish’ music.

EARLY VIOLIN FANDANGOS: THE CATALONIA SOURCES

Fandango music circulated predominantly via aural transmission and, judging from travellers’ descriptions, its performance was semi-improvised; it did not feature regular, predictable structures, but was instead freely varied to suit the specific dancers taking part in any given performance.Footnote 28 The degree of difference between real-life performances remains within the realm of speculation and is impossible to determine. As is the case with other vernacular dance-song types from before the era of sound recording, the surviving musical sources must be interpreted with caution, for any transcription implies a previous act of interpretation.Footnote 29 Most likely, the vast majority of the known eighteenth-century fandango scores were copied by professional musicians who ‘domesticated’ the irregular dance-song of popular tradition in order to make it understandable to classically trained musicians and easy for amateurs to perform.

Despite this limitation, some general musical features of the eighteenth-century instrumental fandango can be deduced.Footnote 30 It generally consists of a set of variations (diferencias) on an isorhythmic pattern based on a chordal ostinato that alternates between the minor and Phrygian modes, most commonly D minor–A major, D minor–G minor–A major and A minor–E major. The harmonic cycle lasts for six or twelve beats; that is, two or four bars in 3/4 or 6/8 time.Footnote 31 Another common feature is the use of descending-scale melodies; a characteristic head-motif is B♭–A–G–F–E–D (in D minor).Footnote 32 In some cases, there is a central contrasting section in the relative major, often called ‘subida’ (literally ‘ascent’), resulting in an ABA ternary form (fandango–subida–fandango).Footnote 33 Interestingly, doubts remain as to the duple- vs triple-time accentuation of the eighteenth-century fandango. Most chamber-music examples are written in 3/4 time, but several plucked-instrument sources include fandango accompaniments where strumming would suggest 6/8.Footnote 34 Most likely, within a predominantly triple-time structure some duple-time passages would be introduced, resulting in hemiola and even polyrhythm.Footnote 35

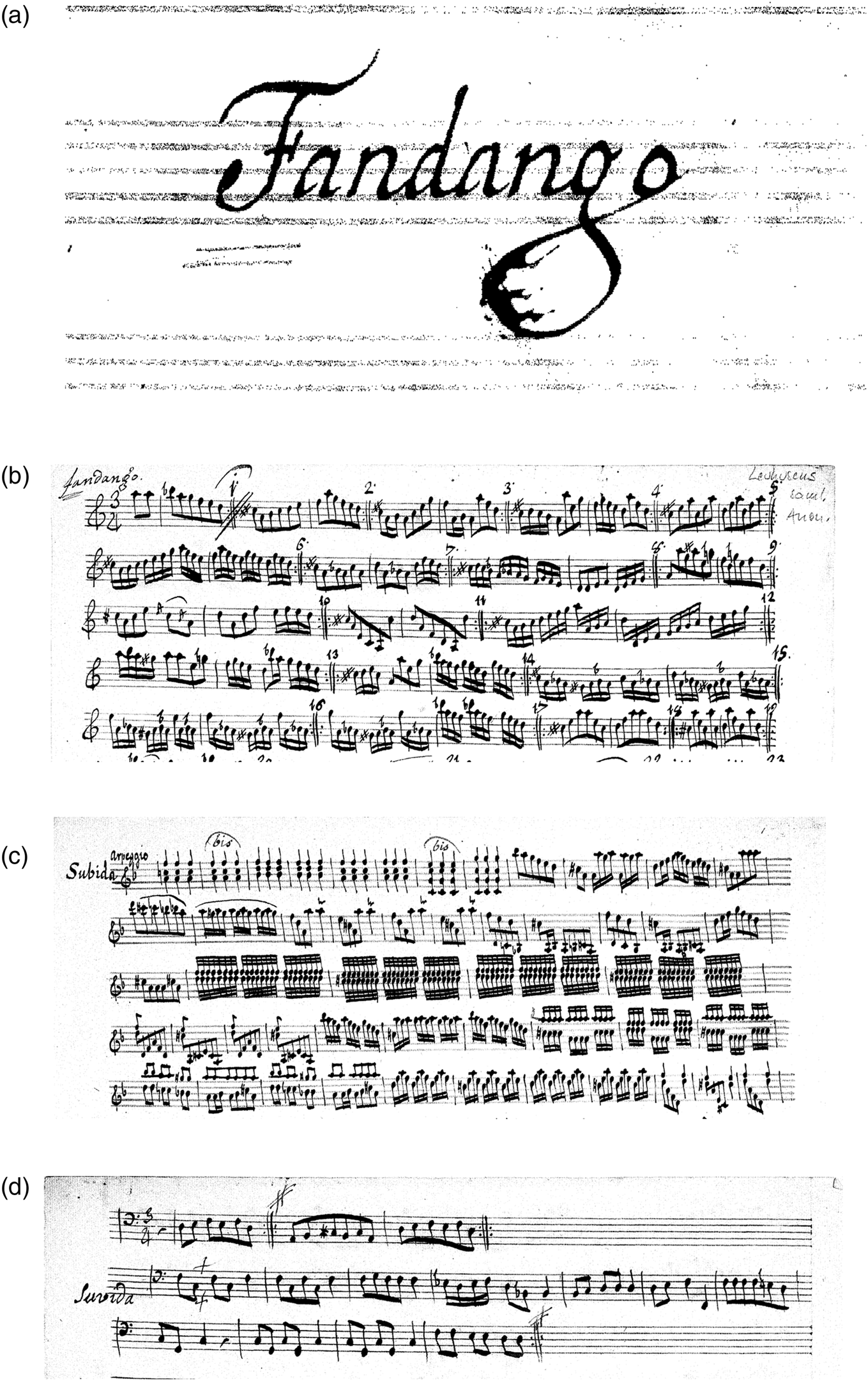

In folkloric and theatrical contexts, fandango music was generally performed by singers and players of plucked instruments, in charge of the melody and the accompaniment respectively; sometimes the same performer sang and played simultaneously.Footnote 36 Other instruments could be used to double the sung melody or indeed simply replace the singer; several musical sources point to the use of the violin for this purpose. To date, the earliest identifiable notations of fandango melodies that are clearly intended for violin are three examples preserved in two different manuscripts in the Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona: ‘Manifestación de relevantes aplausos de la música’ (c1731)Footnote 37 and ‘Folias, Ballets, Sardanas y moltas altras cosas’ (c1731?).Footnote 38 Both are lengthy miscellaneous violin-music compilations of Catalan origin, as is clear from the use of Catalan vocabulary and references to events that took place in Barcelona.

The ‘Manifestación’ manuscript has a didactic function: the prologue discusses fundamentals of music theory, violin tuning and violin scales (fols xi–xii), and the first two sections bear the headings ‘Classe I’ and ‘Classe II’ (Lesson I and Lesson II). This manuscript contains over five hundred violin pieces in the normal treble clef (G2), including dances, marches and diferencias on various patterns, both international (such as minuets) and native Spanish, such as ‘El Fandango’ (fol. 249r, henceforth Catalonia Fandango 1). The other manuscript, possibly copied a few years later, is an anthology of violin repertory that was already becoming old-fashioned at the time it was copied, as its complete title makes clear: ‘Follias, Ballets, Sardanas, Contradansas, Minuets, Balls, Pasapies, y moltas altres cosas de aquell temps vell, que ara son poch usadas; pero ab tot son bonicas y molt alegres’ (Folias, ballets, sardanas, country dances, minuets, balls, passepieds and many other things from the old times that are seldom practised today, but which are still beautiful and very lively). This source contains two fandango melodies: ‘Lo fandango’ (fol. 17r, henceforth Catalonia Fandango 2) and ‘Fandango’ (fol. 60r, henceforth Catalonia Fandango 3).

Transcribing the Catalonia fandangos is problematic, for they do not match naturally the rhythmic-harmonic fandango patterns described above. The scribes, possibly copying from earlier sources, made obvious errors: some bars are too short in No 1, some bars are too long in No. 2, and Nos 1 and 3 contain inconsistent double bars that do not fit into an isometric pattern. Different transcriptions have been proposed by Maurice Esses and Guillermo Castro, but these are not completely convincing, mainly because they do not fit with a fandango bass.Footnote 39 Assuming that each piece is based on a regular isometric pattern over a chordal ostinato, alternative transcriptions can be proposed. As regards accentuation, I have assumed that the pattern of the previous bars is continued; when two options are plausible, this is indicated by ossia.

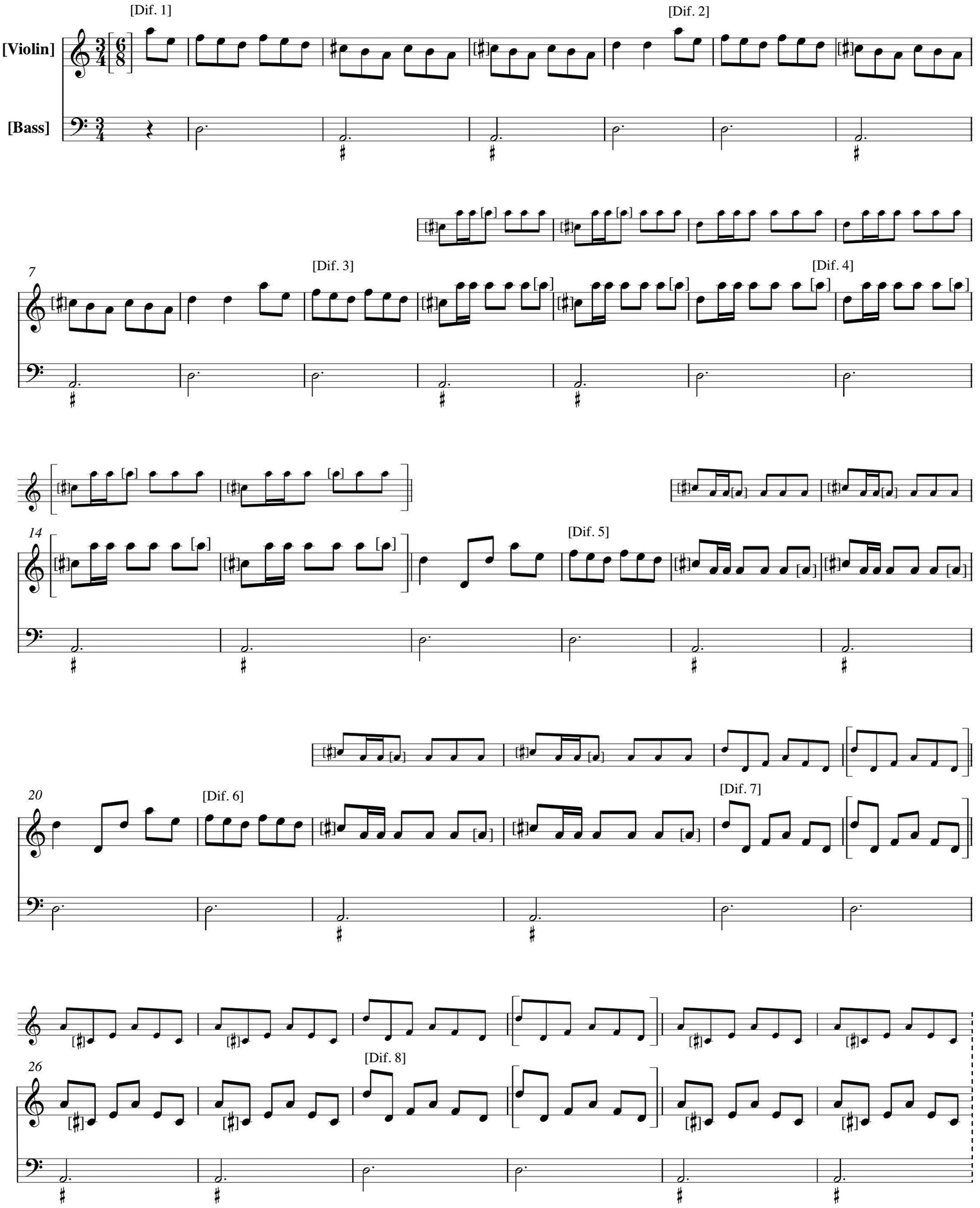

Catalonia Fandango 1, written in 3/4, features the usual D minor–A major harmonic pattern (see Example 1Footnote 40). A natural key signature is used, and the sharp sign for the note C is only indicated in the first instance (bar 2), but can be assumed for the rest of the piece. Judging from the first eight bars, this fandango is made up of four-bar diferencias on an anacrusic D minor–A major–A major–D minor chordal pattern. The beaming suggests that the piece combines binary and ternary accentuation, in bars 1 and 4 respectively. From bar 9 onwards, numerous bars lack half a beat (bars 10–15, 18–19 and 22–23). As regards the beaming, it seems likely that a quaver is lacking in the second or third beat. Two possible solutions can be suggested: a typical seguidilla rhythm (Example 1, main staff) or else a typical jota rhythm (Example 1, ossia); both are also found in eighteenth-century fandangos.Footnote 41

Example 1 Catalonia Fandango 1. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona (E-Bbc), M. 1452, fol. 249r. Critical edition by Ana Lombardía

Catalonia Fandango 2, written in 3/8 and featuring the usual D minor–A major harmonic pattern, is a standard on-the-beat fandango that starts with the typical descending head-motive (Example 2). Interestingly, this is written in a slower tempo than the rest of the piece, with quavers instead of semiquavers, as if to summon the dancers before they actually begin the dance, which presumably occurs at bar 3. A transcription of this piece today is quite straightforward, notwithstanding the rhythmic inaccuracies of the first and last bars.

Example 2 Catalonia Fandango 2. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona (E-Bbc), M. 741/22, fol. 17r. Critical edition by Ana Lombardía

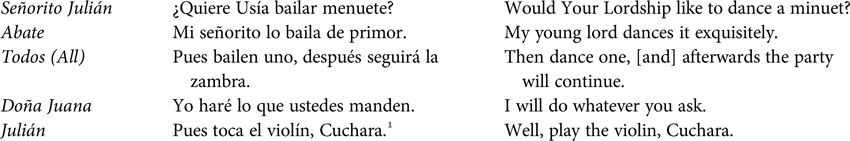

Catalonia Fandango 3, in 3/4, is harmonically more distinct (Example 3). It does not feature a regular chordal ostinato. Diferencia 1 and Diferencia 2 feature an implied A minor–E major–A minor–A minor ostinato (assuming that bar 5 is missing in the source). By contrast, Diferencia 3 and Diferencia 4 feature an implied A minor–D minor–E major–A minor ostinato. G♯ is only notated once (bar 6) but can be assumed in parallel melodic contexts (bar 2). However, it is likely that the scales starting in bar 16 should retain the G natural; that is, it seems that bars 16–19 are not Diferencia 5, but instead a Subida section featuring a hybrid harmonic sonority, between C major and A minor. Diferencia 5 actually starts in bar 20 and features an implied A minor–D minor–E major–E minor bass. By adding half a bar in A minor harmony, this variation can be linked back to the beginning. This example suggests that not all pieces inspired by the fandango were necessarily based on a regular harmonic pattern. Yet the scarcity of contemporaneous melodic sources for the fandango and the idiosyncrasies of this particular scribe – the other two fandangos also contain notational inaccuracies – do not allow for definitive conclusions about this matter.

Example 3 Catalonia Fandango 3. Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona (E-Bbc), M. 741/22, fol. 60r. Critical edition by Ana Lombardía

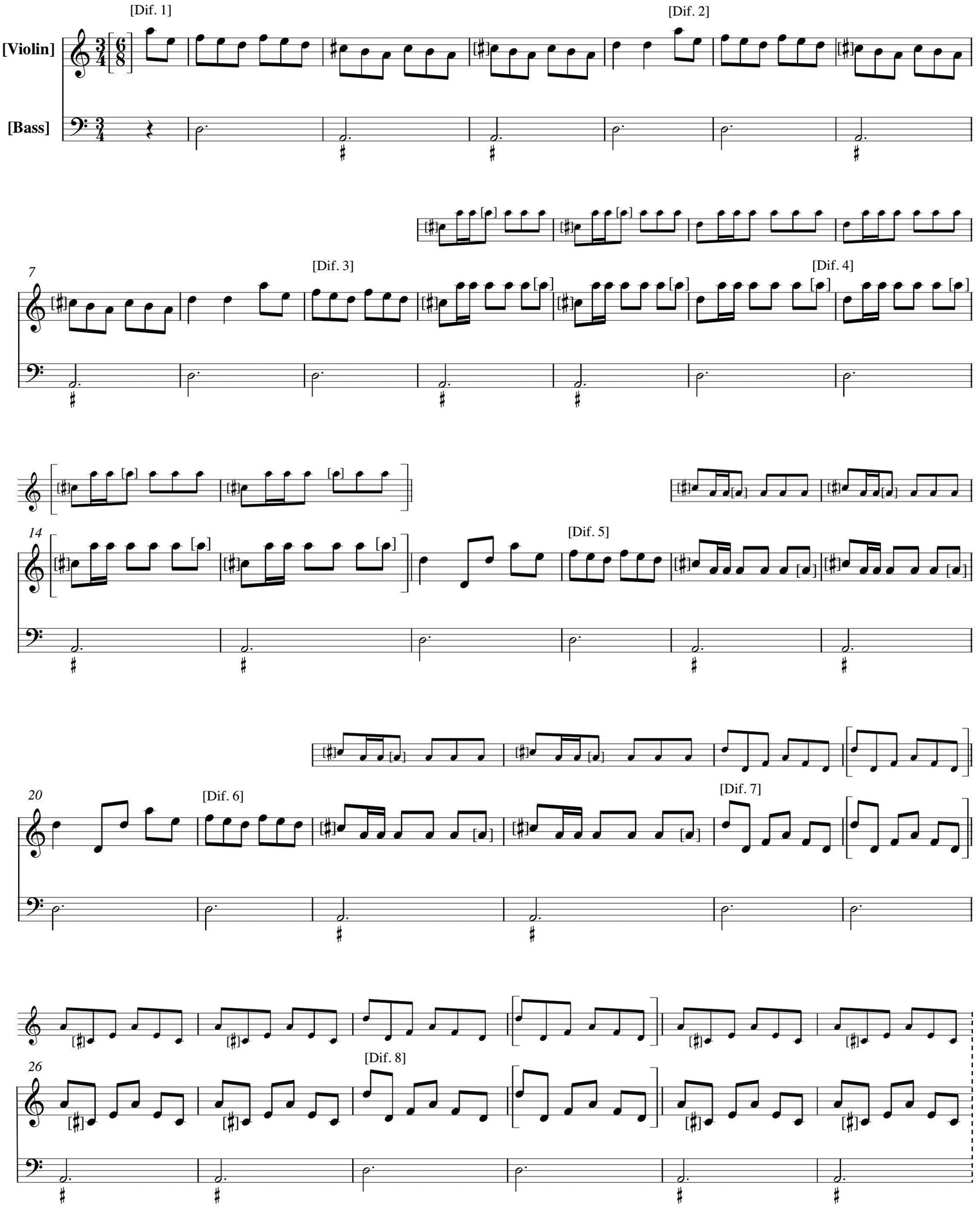

Further analysis shows that these three examples are not exceptional, but that the violin was frequently used to perform dance-orientated and popular-music fandangos. First, it is clear that the usual fandango harmonic patterns are particularly idiomatic for the violin. The D minor, A major, G minor, A minor and E major chords can all be performed with the inclusion of open strings, while two-octave melodies in A minor or D minor are playable using just first to third positions in the left hand. Second, within broader contexts, there are indications in several stage and religious works from the 1730s and 1740s that the fandango is to be performed on the violin. Examples include the sacred Jácara de fandanguillo. Villansico [sic] a 5 de Navidad con violines (manuscript from Málaga, 1733) by Juan Francés de IribarrenFootnote 42 and the seguidilla-fandango ‘Tempestad grande, amigo’ from the zarzuela Vendado es amor, no es ciego by José de Nebra (Madrid, 1744).Footnote 43 Third, it must be remembered that although travellers’ descriptions frequently associate fandangos with the guitar, this does not necessarily discount the possibility of the violin being played in the same performance. In fact, from the mid-seventeenth century the two instruments were used together to perform popular songs and dances; they shared repertory and even notation systems (tablature).Footnote 44 Moreover, several violin and guitar tutors provide instructions on how to tune the two instruments together to play dance music, both Spanish and foreign. For instance, in 1773 Juan Antonio de Vargas y Guzmán explicitly mentioned the performance of ‘minuets, marches, dances, canarios, etc.’ with violin and guitar.Footnote 45 Fourth, some iconographical sources attest to the use of violin and guitar for the performance of ‘Spanish’ music. An example is the title-page of Seis seguidillas voleras [sic] para cantar con acompañamiento de guitarra by José Rodríguez de León (Madrid, 1801). This engraving shows two dancers playing the castanets with arms held open, accompanied by players of violin, flute and guitar, with an audience of a dozen people, some of them wearing majo-style costumes (Figure 1). It is also worth noting that the violin is used in some of the traditional fandango genres currently practised in southern Spain.Footnote 46

Figure 1 José Rodríguez de León, Seis seguidillas voleras [sic] para cantar con acompañamiento de guitarra (Madrid: Imprenta Nueva de Música, 1801). Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid (E-Mn), M/2463(3). Title-page. Used by permission

INTERNATIONAL DISSEMINATION: THE STOCKHOLM SOURCES

Two hitherto unnoticed sets of fandango variations for violin and accompaniment, presumably conceived as listening-oriented chamber works, have been located in Sweden. The manuscript containing both works belongs to the music collection of Baron Carl Leuhusen (1724–1795), part of which is preserved in the Musik- och Teaterbiblioteket, Stockholm (S-Skma). Between 1750 and 1756 Leuhusen worked at the Swedish embassy in Madrid, where he was chargé d'affaires between 1752 and 1755. This polymath diplomat wrote several books on economic issues, sponsored botanical publications and collected a large library on miscellaneous topics.Footnote 47 He was also an avid music-lover. In the Spanish capital he attended opera performances and private musical gatherings, was in touch with the Royal Chapel cellists Domenico Porretti and Juan Orri, visited the latter in his own house and showed interest in buying a cello.Footnote 48 Moreover, the diplomat was interested in local dances, as shown by a letter dated 1752 in which he regrets that, owing to the mourning for the death of Baron Fleming (former chargé d'affaires in Madrid) he was not allowed to attend the balls at which minuets, country dances, seguidillas and fandangos were danced.Footnote 49

Leuhusen collected music manuscripts copied in Madrid and containing chamber works, such as a set of twelve oberturas and sinfonías (c1753) by the Spanish violinist-composer Vicente Basset (fl. 1748–1762), scored for three or four bowed instruments.Footnote 50 He also collected songs based on folkloric music, such as Seguidillas nuevas de Farinelo (1754), attributed to Farinelli (Carlo Broschi).Footnote 51 Leuhusen's collection also contains three of the printed tutors on musical instruments by Pablo Minguet, namely his so-called Reglas (rules) for learning to play the violin, the guitar and the bandurria.Footnote 52 No doubt the diplomat wished to take home some ‘exotic’ musical souvenirs that would have been difficult to obtain outside Spain.

This is also the case with the manuscript entitled ‘Fandango’ (S-Skma, Leuhusens saml. 1930/1768), which, though catalogued in RISM, is still virtually unknown to musical scholarship.Footnote 53 The title-page bears the owner's initials, ‘C. L.’. This undated source contains two works, each copied by a different hand and entitled simply Fandango (henceforth Stockholm Fandango 1 and Stockholm Fandango 2). The manuscript can be tentatively dated to c1755, because of the timing of Leuhusen's stay in Madrid and his personal interest in the fandango, as well as a number of physical similarities between this musical source and specific music manuscripts preserved in the Spanish capital. The format (landscape quarto with ten staves per page) and the calligraphy of both music and text match those of several music manuscripts copied for Madrid's public theatres between 1757 and 1762. All of them contain music by Antonio Guerrero and bear the name of Basset in the violin 1 part.Footnote 54 In those years Basset was a member of María Hidalgo's company orquesta (a small ensemble featuring six to eight string and wind musicians).Footnote 55 In those years, introducing seguidillas and fandangos into theatre music was becoming more and more fashionable. For example, both genres appear in Guerrero's La justa venganza (1757),Footnote 56 and the seguidilla also appears in La hixa de Jepte (1761); the manuscript containing this work is noticeably similar to the one containing the fandangos.Footnote 57 There is not enough evidence to attribute these works to Guerrero or Basset, but it seems plausible that the latter, who was very likely in touch with the Swedish diplomat, obtained this music for him.

In the current state of research, the Stockholm fandangos are the earliest known examples of chamber-music violin fandangos, and some of the earliest chamber-music fandangos in general – only Murcia's and Scarlatti's are dated before 1760. Three facts suggest that these two sets of violin variations were most likely conceived as chamber works rather than functional dance music. First, they belong to the private collection of an amateur who collected other instrumental chamber works in Madrid, probably for performance in his own residence. Second, the violin part is technically demanding, containing devices including multiple stopping, jumps across the strings and fast arpeggios. Third, the second fandango features an unfigured accompaniment in the bass clef – that is, a melodic bass, which is often called ‘bajo solo’ (solo bass) in Spanish sources. This is precisely the same type of bass found in most of the accompanied violin sonatas copied or printed in Madrid between 1750 and 1770. Although the choice of accompanying instruments was very flexible, it seems that the cello, often called ‘violón’ in Spain, was the most common option.Footnote 58 Moreover, it is possible that Leuhusen himself played the accompaniment on the cello, given that he showed interest in the instrument during his stay in Madrid.

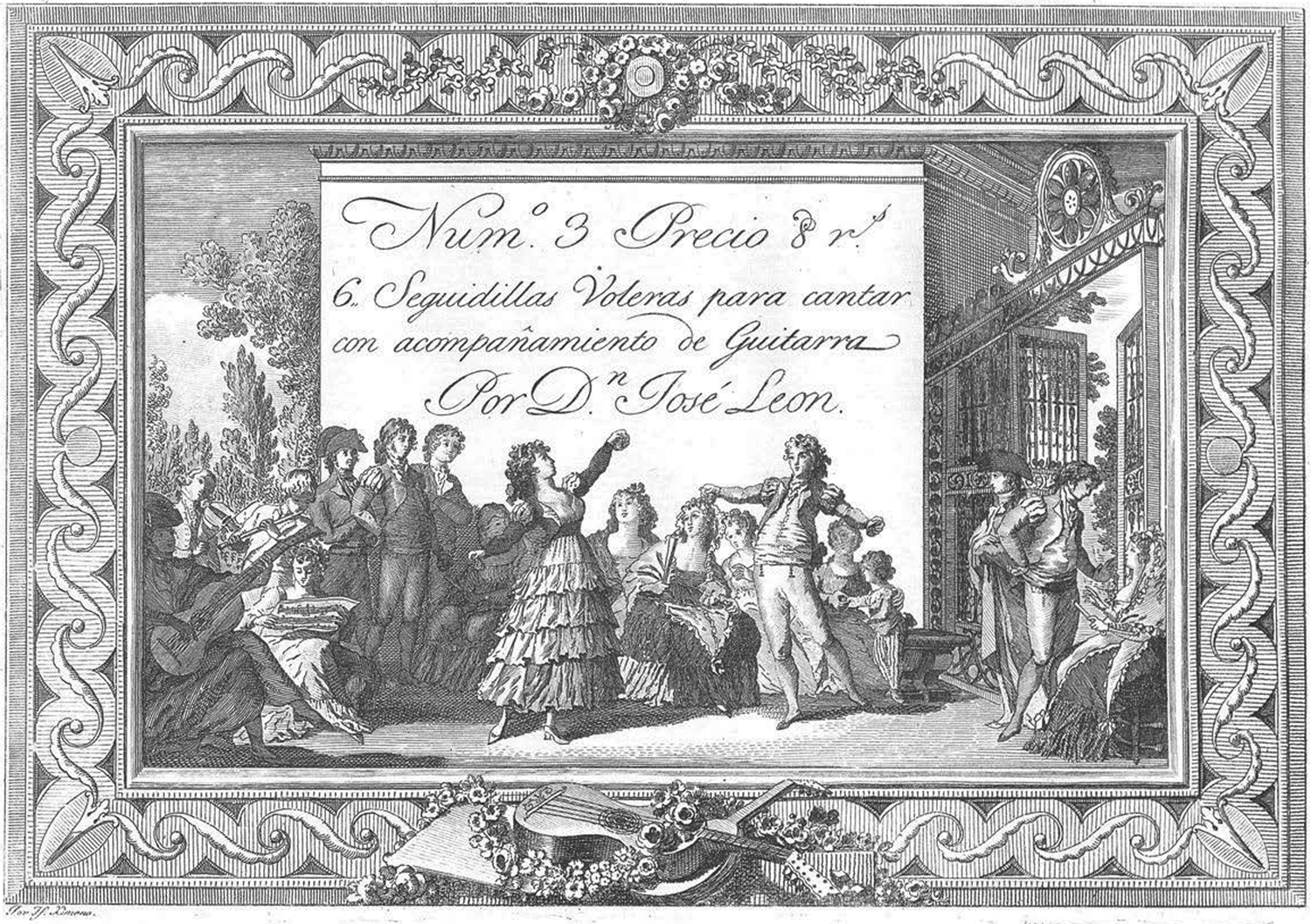

These fandangos are relatively lengthy, technically demanding for the soloist and particularly idiomatic for violin and cello. They are copied over five pages: two for the melodic part of the first fandango, two more for the melodic part of the second fandango, and one for the accompaniment.Footnote 59 The melodic parts are clearly conceived for violin – rather than other treble instruments used in Madrid at the time, such as the oboe and the flute – judging from the use of the treble clef, the range (g–a3) and, above all, the idiomatic instrumental writing. The accompaniment is copied in the bass clef, its range is appropriate for the cello (A–f) and it is unfigured for the most part (save for a big sharp sign indicating A major harmony at the beginning of the ostinato). Both sets of variations are based on the standard D minor–A major chordal ostinato in 3/4, featuring six-beat cycles (Figure 2b and Figure 2c). Their form is identical: typical head-motive (in this case, anacrusic in 3/4 time), variations on the A major–D minor ostinato, a brief subida in the relative major, and more variations. The first fandango is longer than the second, at 183 bars and 135 bars respectively. However, the durations are not fixed, since both copies are open-ended: in the last bar, repetition signs indicate that the music should start again at bar 2, right after the head-motive. Alternatively, one could hypothesize that additional variations may have been improvised. The accompaniment is different in the ‘Subida’ or ‘Suvida’ (No. 1, bars 87–97, and No. 2, bars 91–101; see Figure 2d).Footnote 60

Figure 2 Stockholm Fandangos. Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Stockholm (S-Skma), Leuhusens saml., 1930/1768. Used by permission

a. Title-page, detail

b. Stockholm Fandango 2, Violin, page 1, introduction and variations 1–18

c. Stockholm Fandango 1, Violin, page 2, bars 87–137 (the initial bars of each system are bars 87, 99, 110, 115 and 125)

d. Stockholm Fandango 2, accompaniment

Both solo parts employ a variety of features from the standard vocabulary of eighteenth-century sonatas for solo violin: scales, arpeggios of various kinds, chromatic scales, double stops (thirds, sixths and octaves) and so on. Technical demands are higher in the first fandango, where the range reaches the violin's left-hand fifth position (a3), while it is limited to the first position in the second fandango (b♭2). Neither piece needs complex fingerings, and much of the music can be played with the regular use of open strings, thus facilitating the performance of seemingly flashy technical devices (for example, No. 1, bars 124–126; Figure 2c). Other idiomatic gestures are the use of seeming dialogues between two different registers (No. 1, bars 107–110; Figure 2c), pedal notes, and groups of notes used as a pedal (No. 2, variations 14–17; Figure 2b). All of these resources are part of the lingua franca of eighteenth-century violin music, synthesized and spread through such collections as Corelli's Op. 5, which was known in Spain at least as early as 1709.Footnote 61 In the Stockholm Fandango 1, the technical difficulty increases towards the end (bars 113–183), containing double stops, jumping across strings, arpeggiated chords, fast scales and a final passage in the highest register.

The melodic variations feature great rhythmic variety, and contrasting cells are juxtaposed (for example, triplets and syncopation in No. 2, variations 53–54). The copyists generally use one-beat beaming (for example, four semiquavers, two quavers, and so on), but some bars feature two- or three-beat beaming, or even three-quaver beaming (for example, No. 2, variation 37). This presumably indicates accentuation changes from 3/4 to 6/8, and some hemiolas, as in other eighteenth-century instrumental fandangos. Consecutive variations are often interrelated, in a rhapsodic fashion, as if they were in fact a transcription of an improvised performance. For instance, the scales of variations 11–17 of the Stockholm Fandango 2 are clearly conceived for performance with no breaks or repetitions (Figure 2b).

Although the uninterrupted flow of continuously juxtaposed variations lacks articulating ‘gaps’, the motivic variety of these fandangos resembles that of mid-century violin sonatas in the galant style. Well-known examples include the works of Locatelli and Tartini,Footnote 62 but there were some twenty violinist-composers, roughly half of them Italian and the other half Spanish, composing this kind of sonata in Madrid during the 1750s and 1760s.Footnote 63 Given that the violin vocabulary of these fandangos is highly conventional, it is not possible to propose a specific attribution, but their idiomatic writing points to a violinist-composer. Furthermore, variety focuses mainly on melodic and technical devices, rather than on formal and harmonic strategies (which are more characteristic of keyboardist-composers like Scarlatti and Soler, whose fandangos are more varied in this regard).

For all these reasons, the Stockholm fandangos constitute a unique witness to the merging of irregular fandango structures, the melodic variety of the galant-style accompanied violin sonata and the melodic bass that was typically used for the performance of this kind of sonata in Madrid. Leuhusen left Spain in 1756, taking his music collection to Sweden.Footnote 64 In his property Degarö in Uppland (the province just north of Stockholm), the diplomat collected a large library containing economic, philological, historical and scientific literature.Footnote 65 Most likely the music collection was also taken there, where Leuhusen had a harpsichord in 1768.Footnote 66 Moreover, shortly after the return from Spain, on 3 April 1758, Leuhusen wrote a list of his winter entertainments being held in that property, and music was second on the list (only after literature).Footnote 67 One may speculate that the ‘Spanish’ scores may have been used in private musical gatherings there, perhaps making the ‘exotic’ violin fandangos known to other Swedish music amateurs. Future research on Leuhusen's musical activities may allow this hypothesis to be confirmed. For now, however, these musical sources can be regarded as an early example of the dissemination of this musical pattern in northern Europe.

HYBRIDIZING THE FANDANGO: MIXED COUNTRY DANCES

A different combination of styles is found in another genre that originated in mid-eighteenth-century Spain and involved both the fandango and the violin: the mixed country dance. They can be considered the eighteenth-century equivalent of the nineteenth-century potpourri and the twentieth-century remix: some of the most commercially successful rhythmic-melodic patterns of the time were juxtaposed one after the other. Not only the music but also the steps were mixed, including those of supposedly ‘native’ dances, such as the seguidilla and the fandango, as well as others introduced to Spain from France, such as the minuet, the allemande and the country dance (contradanza in Spanish).

The latter, generally to be considered of English origin, was introduced into Spain from France in the first half of the eighteenth century, and soon Bartolomé Ferriol and Pablo Minguet described it in dance tutors in Spanish. They differentiate between English and French contradanzas, based on choreographic criteria (the English or ‘long’ type was danced by a flexible number of dancers in two rows, while the French or ‘squared’ type was danced by four couples forming a square).Footnote 68 The mixed country dances are documented by the tutors that were written in connection with the public masked balls of the late 1760s and 1770s. Such balls, supported by the Crown as part of a set of innovative political measures, were modelled on those of Paris and became some of the main social events in Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Seville.Footnote 69 Amateurs were eager to learn the new dances, and that stimulated a large demand for tutors, usually published in small format so one could hold the book while dancing. Typically, dance handbooks include choreographic explanations on the right-hand page and the corresponding melodies on the opposite page, written in treble clef.

To date, several studies have paid attention to the dissemination and choreographic practice of mixed country dances,Footnote 70 but their connection to the violin repertory has been overlooked. Such a connection is clear given that violins were used precisely to play the melodies that were copied in the dance tutors, as part of large orchestras of bowed and wind instruments. Tellingly, a handbook related to the 1768 Barcelona balls specifies two orchestras numbering forty-four musicians in total (providing specific musicians’ names). The first orchestra had sixteen violins, four baxos (accompanying instruments, such as the cello and the double bass), two clarines (trumpets) and two obueces (oboes), while the second orchestra had fourteen violins, four baxos, two trompas (horns) and two obueces (oboes).Footnote 71 Although this handbook only gives the violin melodies, it specifies that ‘the rest of the instrumental parts can be found at the house of Joseph Fábregas, composer of the music, Rey Square’ (‘Se hallarán los demás instrumentos à casa de Joseph Fábregas, autor de la música, Plaza del Rey’).Footnote 72

No doubt mixed country dances made up a part of the repertory of professional violinists, and most likely amateur violinists played them as well. By 1771, the violin had become sufficiently popular in Spain to stimulate the publication of four different printed tutors, all of them including music examples in the form of dances, mostly minuets.Footnote 73 The tutor by Manuel de Paz (Madrid, 1767) also includes a country dance, although it is confusingly called ‘Fuga’.Footnote 74 Most likely, the target market for violin tutors overlapped with that for dance tutors: that is, middle- and upper-class amateurs wishing to acquaint themselves with the cosmopolitan musical fashions that had been recently imported from France. In other words, both activities were hobbies of the petimetres. In private rehearsals of country dances, one can imagine that both the music and the dance were performed by amateurs, including the violinists playing the melody.

Two well-known examples of mixed country dances whose music has survived in violin-range staff notation are La miscelánea (The miscellany) and La fandanguera (The fandango dance). Concordances are found in various country-dance compilations from Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia; one of the most complete is the manuscript ‘Varias contradanzas con sus músicas’ (Madrid, c1770).Footnote 75 In such compilations, country dances are divided into the two above-mentioned categories, according to their choreography: contradanzas francesas (French country dances), also called contradanzas de a ocho (eight-people country dances) or contradanzas cuadradas (squared country dances); and contradanzas inglesas (English country dances), also called contradanzas largas (long country dances). Both La miscelánea and La fandanguera are contradanzas de a ocho, as is indicated in Varias contradanzas con sus músicas.

The choreographical explanations given in this source make clear which type of music was performed in each section. La miscelánea is made up of four anacrusic phrases (Example 4): Alemanda (4 + 4 bars), Diferencia (a variation on the Alemanda, 4 + 4 bars), Seguidillas (6 bars) and Fandango (6 bars). There are no key signatures, and accidentals are lacking for the most part, but a D minor tonality is implied, with the exception of the opening gesture of the Diferencia, which is in the relative major (bars 9–12). It is explained that the Fandango section had a particular function, namely to make the dancers ‘go back to their places in fandango steps’.Footnote 76 Here the music is a variant of the typical fandango head-motive, featuring the D minor–A major harmonic pattern.

Example 4 Anonymous, ‘La miscelánea de a ocho’, in Varias contradanzas con sus músicas, No. 7 (Madrid, c1770). Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid (E-Mn), M/918, fol. 7v. (All additions are in square brackets. Section titles are based on the choreographic descriptions in the same manuscript.)

La fandanguera illustrates a different combination of music and dance patterns (Example 5). It is made up of three sections: Country Dance (4 + 4 bars), Minuet (11 bars), Fandango (4 bars) and a final cadence. The two-flat key signature makes clear the use of two main tonalities: G minor in the country dance, B flat major in the minuet, and a G minor–D major pattern in the fandango. This last section is played three times, as indicated in the score (‘tres veces’). It also begins with the usual head-motive, which is briefly developed in a four-bar melody. Again, the dancers are supposed to ‘go back to their places in fandango steps’, but in this case the music ‘concludes’ once they are back in their starting position.Footnote 77

Example 5 Anonymous, ‘La fandanguera de a ocho’, in Varias contradanzas con sus músicas, No. 34 (Madrid, c1770). Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid (E-Mn), M/918, fol. 21v. (All additions are in square brackets. Section titles are based on the choreographic descriptions in the same manuscript.)

The mixed country dances provide additional evidence that the violin was used to perform fandangos and derivations of it. Moreover, they attest to the mixing of ‘Spanish’ music and dance patterns with foreign ones that had been introduced from France, such as the minuet and the country dance. The fact that these ‘remixes’ appear in numerous sources from different Spanish cities reflects the integration of local and international musical practices, thus challenging traditional discourses about the opposition between majismo and cosmopolitanism. In the 1790s satirical writers showed their disgust at the ‘contamination’ of native Spanish traditions,Footnote 78 but in the 1760s and 1770s, music and dance amateurs in Spain had no prejudices against such hybrid cultural products.

AN EXOTIC PIECE: GIARDINI'S FANDANGO

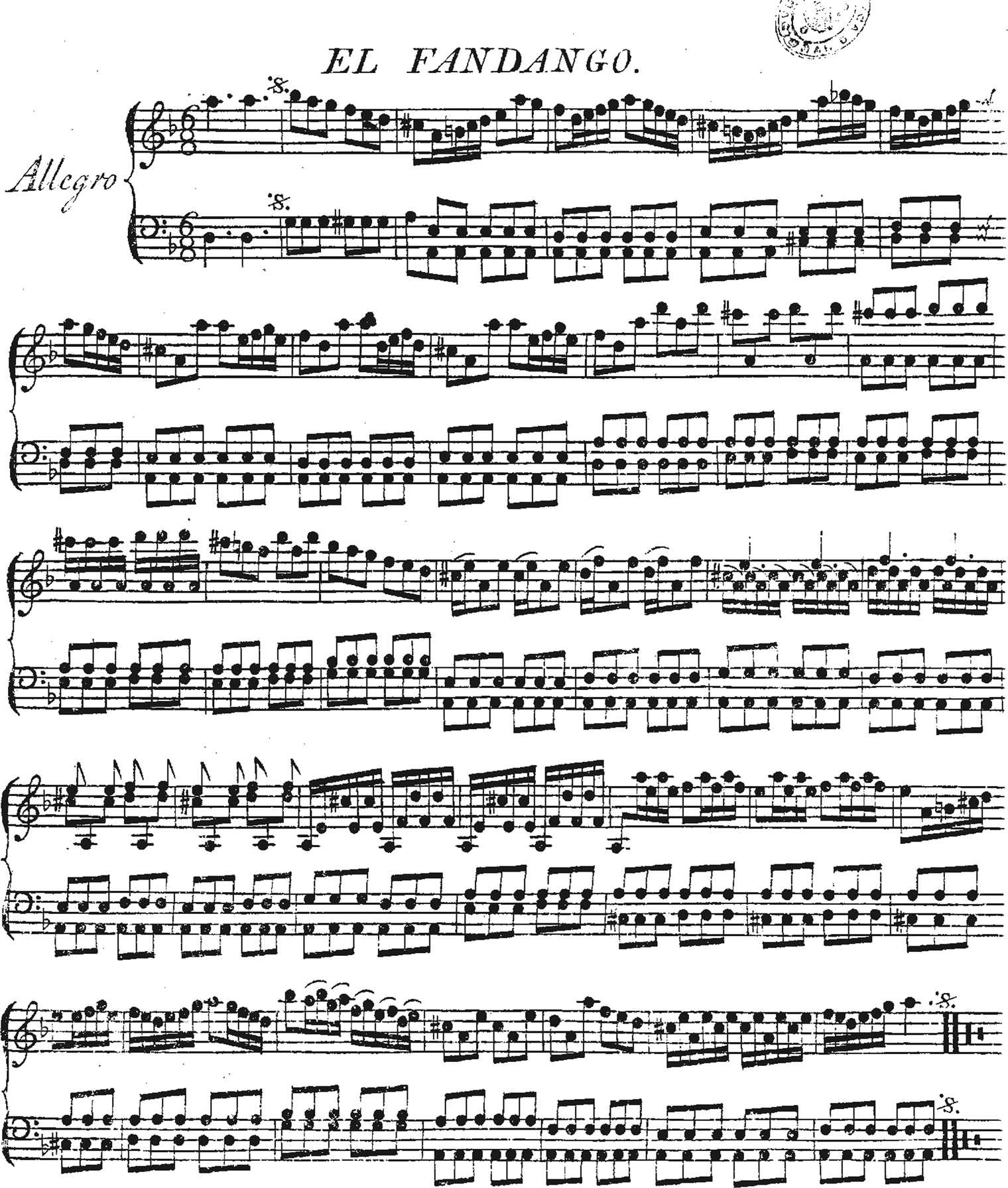

To date, the piece titled ‘El Fandango’ published by Richard Twiss (Figure 3) has been regarded as a primary source for the music actually heard in vernacular fandango performances. It appears next to the author's description of his visit to Madrid. Twiss comments on the great success of the fandango, both in public balls and in private assemblies:

The amphitheatre [Teatro del Príncipe], constructed in 1767, is a plain oval building, with three rows of galleries over each other. During the carnival here are sixteen masquerades exhibited. The other evenings of that season of dissipation, are allotted to dancing fandangos, minuets, and English country-dances. Mr. Baretti gives an account of this edifice, and the fandango, which, though I had no opportunity of seeing in public here, by reason of its being Lent, yet I saw danced in various private assemblies in Madrid, and afterwards in every place I was in. The fury and ardour for dancing with which the Spaniards are possessed on hearing the fandango played, recall to my mind the impatience of the Italian race-horses standing behind the rope . . .

There are two kinds of fandangos, though they are danced to the same tune: the one is the decent dance; the other is gallant, full of expression, and, as a late French author energetically expresses it, ‘est mêlée de certaines attitudes qui offrent un tableau continuel de jouissance’ [is mixed with certain dance positions that offer a vision of continual enjoyment].Footnote 79

Figure 3 Mr Giardini, ‘El Fandango’, in Richard Twiss, Travels through Portugal and Spain in 1772 and 1773 (London, 1775), plate facing page 156. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid (E-Mn), ER/5275. Used by permission (the initial bars of each system are bars 1, 6, 13, 20 and 26)

Twiss goes on to cite a definition from a 1769 Antwerp dictionary that relates the fandango's origin to the ‘Indians’ (people from the (West) Indies) and declares, ‘I know not what foundation there is for this assertion’.Footnote 80 He then compares the music of the folia and the fandango, citing the musician ‘Mr Giardini’:

The modulation of the follia is exactly similar to that of the fandango, and the name farther demonstrates the truth of this assertion.*

[Footnote] *This remark was suggested to me by Mr Giardini, who has likewise been so obliging as to set a bass to the fandango, of which the notes are inserted in the annexed plate.Footnote 81

It has been suggested that Giardini may have been an Italian musician based in Madrid in the early 1770s,Footnote 82 but there is no trace of such a person in the existing studies of the city's musical life.Footnote 83 Alternatively, Twiss may have been referring to the London-based violinist Felice Giardini (1716–1796), who would have been well known enough to Twiss's readership to be called simply ‘Mr Giardini’.Footnote 84 A plausible hypothesis is that Twiss obtained a transcription of a fandango melody in Spain which he gave to Giardini in London, and the latter wrote an arrangement with bass. Indeed, the piece in Twiss's book bears a resemblance to Giardini's compositions for strings, which generally reflect the lingua franca of the galant style and an idiomatic instrumental technique.Footnote 85

More specifically, ‘El Fandango’ is written for a melodic instrument in treble clef and unfigured bass. The range and the instrumental writing are appropriate for violin and cello. The treble part is particularly idiomatic for the violin: the range matches the first three positions of the instrument (a–d3), pedal notes can be played on the lowest string (such as the a of bars 20–24), double stops are simple ones in the first position (c♯2–e2 and d2–f2, bars 20–21) and involve a rapid crossing to the G string between iterations, while arpeggios are easy to perform in static left-hand positions, in the manner of Corelli (as in bars 22–23). This piece, written in 6/8, features the typical fandango head-motive (bars 1–2), after which a standard A major–D minor chordal ostinato begins. This is maintained at a two-bar harmonic rhythm for most of the piece (bars 3–10, 16–19 and 29–32); but it is sped up to a one-bar frequency in bars 11–14 and 20–25, while subdominant harmony is used as a nexus before the return of the ostinato (bars 15 and 28). The repeat sign in bars 2 and 32 indicates that this is an open-ended piece, subject to further variations. However, strictly speaking there is not a regular harmonic pattern throughout the piece, so it is difficult to believe that it was actually a part of the folkloric tradition and that, as Twiss claims, ‘the same tune’ was played all over Spain. Most likely, this is a stylized version of the transcription that reached Giardini.

This was not the first time that a supposedly ‘Spanish’ musical product arrived in London. By the time Twiss's book was published, exoticism had become a key commercial hook in the city's music market.Footnote 86 In the field of instrumental music, the presence of a large number of foreign names in publishers’ catalogues became a sign of distinction.Footnote 87 Spain was not an exception: the collection Eighteen New Spanish Minuets for Two Violins and a Bass was published in London at least twice, first by John Cox (1758)Footnote 88 and also by John Johnson (before 1762).Footnote 89 The title-page announces the names of six allegedly Spanish composers: ‘Errando, Espinosa, Cabar, Camusso, Luna and Narcisso’. Errando and Espinosa are likely to be the violinist José Herrando (c1720–1763) and the oboist Manuel Espinosa (c1730–1810). Both of them worked for Madrid's Royal Chapel and enjoyed some fame in Spain during their lifetime. Moreover, Herrando wrote similar minuets in his violin duets and tutor.Footnote 90 Given that the style of this music is highly conventional, though, it is risky to make attributions.

Since ‘exotic’ instrumental music was commercial in London in the 1770s, the presence of Giardini's fandango in Twiss's book was probably intended to appeal to potential buyers. Interestingly, the piece was later transformed into a piano rondo by Benjamin Carr, who published it as Spanish Fandango in Baltimore around 1797. By then, the fandango's popularity had reached the amateur music market in the United States as well, in such cities as Boston, New York and Philadelphia.Footnote 91

CONCLUSION

The musical examples discussed here demonstrate that the violin was used in the performance of fandangos, whether functional dance pieces or stylized chamber-music variations, well before the rise in popularity of casticismo. This becomes clear from the analysis of evidence pertaining to a wide geographical and chronological context: Catalonia in the 1730s, Madrid in the 1750s, Barcelona and Madrid in the balls of the 1760s and 1770s, and again Madrid (in a London arrangement) in the 1770s. Some of these pieces are of a hybrid nature, merging the fandango with ‘foreign’ dance types (for example, the country dance and the minuet in La fandanguera), genres (the accompanied violin sonata in the Stockholm fandangos) and styles (the galant-style melodic variety and idiomatic violin writing in the Stockholm and London sources). These features demonstrate hitherto overlooked negotiations between highbrow and popular culture in mid-eighteenth-century Spain, as well as the adaptation of supposedly ‘Spanish’ elements for an international and cosmopolitan music market.

Through the medium of violin music, the fandango had reached European countries such as Sweden and England before 1775. The Stockholm fandangos, most likely copied in Madrid during the 1750s, are a particularly important discovery, since they are some of the earliest chamber-music fandangos known so far. Future research may enable us to reconstruct the chamber-music gatherings that Carl Leuhusen attended or organized in Spain and Sweden, where this music could have been performed. As for the fandango published by Richard Twiss, it should no longer be regarded as a primary source, but rather as an arrangement, probably made by Felice Giardini in London. This piece can be now understood as one of the numerous ‘exotic’ musical products that circulated in the British capital during the 1770s.

Furthermore, these eight pieces shed new light on the melodic and rhythmic flexibility of the eighteenth-century fandango. The usual descending head-motive appears in 3/8, 6/8 and 3/4 time in different sources. Moreover, the alternation of binary and ternary accentuation is strongly suggested by beaming in the manuscript containing the Stockholm fandangos. In future research, diachronic analysis of the fandango's rhythmic transformations might be extended through the examination of a broader musical corpus including zarzuelas, villancicos, tonadillas and other genres that incorporate the fandango,Footnote 92 often in the violin part.

From a broader perspective, the pieces examined here contribute to a deeper understanding of the eighteenth-century fandango and challenge traditional discourses on this dance-song type and on the shaping of musical ‘Spanishness’. During the eighteenth century, it was not just plucked instruments but also the violin – paradoxically associated with foreign musical modernity – that took part in this process. In this context, the guitar/violin dichotomy in Ramón de la Cruz's El fandango de candil quoted at the outset of this article can be understood as a literary device; for the audience, hearing a violinist playing the fandango would not have been shocking, but just less effective in that particular dramatic context. This sainete was premiered in 1768, precisely when the popularity of the mixed country dances was reaching its climax. The great success of such hybrid cultural forms shows that the opposition between majismo and Gallicized cultural trends is a historiographical construction; in fact, in Spain's musical life the two currents coexisted and even merged with each other (a later example is the minué afandangado, which was popular in the 1790s).Footnote 93

This notion of historiographical construction recalls W. Dean Sutcliffe's observation that ‘“Spanishness” is what we or a composer construct as being Spanish; it is in the first instance a question of tradition, of cultural determination, rather than one of essence’.Footnote 94 Despite the long-lasting association of the fandango with Spain's cultural essence, its music was transformed and manipulated in various ways from an early date, both within and beyond the country's borders. It is doubtful, even, that this dance-song type originated in mainland Spain, given that the earliest located dictionary definitions and musical sources point to Latin America as the starting point of an open-ended process of hybridization and transformation . . . as open-ended and unpredictable as an improvised set of fandango variations.