Wer auff einen vollstimmigen Instrumente ex tempore zu præludiren sich unterstehet, der muß schon viel Music im Kopffe haben, i. e. er muß mit einem Worte ein erfahrner, und geübter Musicus seyn. Weil sich aber dieser Gradus parnassi nicht in einem Jahre ersteigen lässet, zumahl wenn alles auff eigene Erfahrung allein ankommen soll: so fraget sich, ob man ungeübten keine sichern præcepta oder Anleitung geben könne, wie sie nach und nach selbst eine eigene Harmonie auff ihren Instrumente zu wege bringen, oder mit einem Worte præludieren lernen sollen? Antwort: Ungeübten Musicis allhier die vielerley Arthen der præludien nach allen Fundamentis beyzubringen, ist so unmöglich, als dazu nothwendig ein ganzer Tractat, und nicht wenige Zeilen eines Capitels erfodert würden: die prima fundamenta aber zum præludiren hier zu entwerffen, solches gehet wohl an, und das wollen wir so kurz als möglich auff folgende Arth bewerckstelligen.Footnote 1

Whoever ventures to play a prelude ex tempore on a polyphonic [literally, full-voiced] instrument must already have much music in his head: he must, in short, be an experienced, practised, musician. But because these Steps to Parnassus cannot be scaled in a year, particularly if everything is to depend on one's own experience, the question arises: are there no sure principles or instructions that could be given to the inexperienced so that they, little by little, could bring forth their own harmony on their instrument, or put another way, so they could learn to play a prelude? Answer: to teach the inexperienced the numerous ways of preluding according to all the foundations is so difficult that it would require an entire treatise, not a few lines of one chapter. But we only wish to discuss the first foundation of preluding; this is our concern, and we would like to manage this as briefly as possible in the following way.

Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729) is certainly to be counted among the most perceptive and articulate of baroque theorists. Yet his one-thousand-page magnum opus, Der General-Bass in der Composition (Dresden: author, 1728), a dramatic expansion of his Neu erfundene und Gründliche Anweisung (Hamburg: Benjamin Schiller, 1711), has been perpetually overshadowed in historical accounts by two works published in the same decade: Jean-Philippe Rameau's Traité de l'Harmonie (Paris: Ballard, 1722) and J. J. Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum (Vienna: Johann Peter van Ghelen, 1725). One of the goals of the present article is thus to elevate Heinichen from the rank of mere ‘thoroughbass pedagogue’ to the status of bona fide ‘theorist’, worthy of standing beside Rameau and Fux. To do so by no means diminishes the significance of Rameau's and Fux's contributions, for indeed, both authors established enduring theoretical and pedagogical legacies, each in his own way. The retrospective Fux, with his (in)famous five species, codified the stile antico within a moralizing nostalgia aimed at a largely fictional ‘Palestrina style’. In contrast, Rameau the progressive sought a rational-empiricist explanation for harmonic generation and progression, codifying the two within his theories of son fondamentale and basse fondamentale respectively. Each author's choice of language is telling. Unsurprisingly, Fux's conservative treatise was originally published in Latin, while Rameau penned his in French, the international scientific language of the day.

In contrast, Heinichen's treatise struggled to reach an audience outside Germany, only went through one edition and has until now never been translated.Footnote 2 In fact, it was largely through David Kellner's Treulicher Unterricht im General-Bass (Hamburg: Christian Herold, 1732) that Heinichen's ideas reached a wider audience in Germany, if only indirectly. While Heinichen's 1728 treatise is the longest and most detailed study of thoroughbass ever written, Kellner's much shorter treatise, which encompasses a mere one hundred pages, was the most popular work on the subject in the eighteenth century, if not of all time.Footnote 3 The extensive circulation of Kellner's treatise is significant because his work is in essence a digest of Heinichen (an influence Kellner openly admits). Moreover, Kellner's treatise has recently been shown to have strong connections to J. S. Bach. For these reasons, Robin A. Leaver and I have undertaken the first English translation of Kellner's publication.Footnote 4 Unlike Kellner's enormously popular work, the geographically limited initial dissemination of Heinichen's 1728 treatise set the trend for the work's limited impact in subsequent centuries, with the result that the influence of Heinichen's theories is hardly felt today outside German-speaking countries, apart from the work of George Buelow in the 1960s.Footnote 5 And even in German scholarship, the attention paid to Rameau and Fux far outweighs that devoted to Heinichen as a theorist.Footnote 6

Notwithstanding the intimidating dimensions of Heinichen's treatise and its correspondingly high cost, one senses that this discrepancy can be attributed primarily to two factors.Footnote 7 First, although Heinichen was a progressive in many regards, the overarching ambition of his theoretical project – the rationalization of the modern Italian recitative style as an extension of the prima pratica – remained merely a continuation of seventeenth-century endeavours. That is, Heinichen's theories still defined style in terms of norms and deviations, even if he admitted more liberal deviations than his predecessors. As a result, Heinichen's stylistic modernism paled next to Rameau's methodological modernism, which drew from recent scientific developments in acoustics and mathematics, particularly in his later publications. A second reason why Heinichen's treatise failed to achieve greater popularity is that it lacked an overarching reductive pedagogical framework that could rival Fux's species or Rameau's basse fondamentale in simplicity and appeal. Heinichen's theoretical outlook was far too complex and heterogeneous, owing in part to his nuanced and dynamic responsiveness to the vagaries of musical practice.Footnote 8 The result of these two factors was that, in the course of the eighteenth century and beyond, progressives flocked to Rameau while conservatives clung to Fux, with Heinichen seemingly forgotten in limbo between the two.Footnote 9

Yet, in truth, there are worlds to discover in Heinichen's writings – far more than is generally known. Where else can one find such subtle, detailed and extensive discussions of topics as varied as chord formation and progression, dissonance treatment, accompaniment, contrapuntal licences, ornamentation, modulation, style and aesthetics? Indeed, writing in 1758, Jacob Adlung (1699–1762) still had high praise for Heinichen's 1728 treatise, writing that ‘This is one of the best books we have on thoroughbass’ (‘Dieses ist eins von unsern besten Büchern, welche wir vom Generalbaß haben’).Footnote 10 In fact, buried within the thousand-odd pages of Heinichen's 1728 treatise is at least one section that does offer a pedagogical method of eminent simplicity and practicality on a par with both Fux and Rameau: a four-step method of improvising a prelude at the keyboard. Yet, surprisingly, Heinichen's method seems to be completely unknown today. A further goal of this article is to explicate both Heinichen's method and its historical significance. I argue that his four steps are no mere propaedeutic for the novice improviser. Rather, they represent a compelling model of eighteenth-century compositional pedagogy – a model that has important ramifications both for historically oriented analysis and for keyboard instruction today.

Heinichen stands out among his German contemporaries in the extent to which he holds thoroughbass improvisation and composition not merely to be related, but to be two sides of the same conceptual coin. Indeed, this equivalence is made explicit in the very title of his 1728 treatise: ‘Thoroughbass in Composition’ (Der General-Bass in der Composition), the true sense of which is more like ‘Thoroughbass as Composition’. Of course, Heinichen was not the first to equate the two entities. The earliest authors to do so explicitly in German-speaking lands were Andreas Werckmeister (1645–1706) and Friedrich Erhard Niedt (1674–1717), the latter of whom also put forth his own method of teaching keyboard improvisation, a method that shares important similarities with Heinichen's. (Though there is no direct evidence that Heinichen knew Niedt's work, it seems likely.)Footnote 11 For both Heinichen and Niedt, preluding on a thoroughbass and composing are both expressions of the same underlying music-theoretical principles – one improvised, the other notated.Footnote 12 Significantly, J. S. Bach held a similar position, since he once wrote a testimonial for his student Friedrich Gottlieb Wild (1700–1762) in which he attested that Wild ‘has taken special instruction from me in clavier, thoroughbass and the fundamental principles of composition that are derived from them’ (‘Wild [habe] sich bey mir gar speciell in Clavier, General-Bass und denen daraus fließenden Fundamental-Regeln der Composition informieren laßen’).Footnote 13 This correspondence regarding the significance of thoroughbass in compositional instruction may be part of the reason Bach was willing to act as an agent for Heinichen's 1728 treatise, selling it on commission out of his home in Leipzig.Footnote 14

Of course, the last decade of research into the teaching methods of eighteenth-century Italian conservatories has revealed that neither Heinichen nor Bach were unique among their European contemporaries in equating thoroughbass with composition. Italian instruction during this time often revolved around partimento, a pedagogical genre in which a brief figured or unfigured bass line is realized at the keyboard as a polyphonic composition. Through regular practice beginning at a young age, pupils at Italian conservatories eventually became highly proficient in improvising their partimento realizations, thus providing ideal training for becoming composers and music directors on the international stage. The current ‘partimento renaissance’ has brought welcome attention to this uniquely Italian practice.Footnote 15 Yet the theoretical basis of partimento – thoroughbass – is nothing new, nor is it exclusively Italian. As Felix Diergarten has argued, it seems that thoroughbass has undergone a sort of rebranding in the last decade.Footnote 16 German Generalbass, which sometimes has connotations of being tedious and proscriptive, has suddenly gained a new lightness when reframed as a creative Italian art. But the principles of Generalbass and basso continuo are in essence identical. Thus the time has come to widen the scope of the current ‘partimento renaissance’ to become a true ‘thoroughbass renaissance’. As such, our purview should be expanded to include thoroughbass sources stemming from all over Europe, not just south of the Alps.Footnote 17 To be sure, much energy has been devoted to examining the dissemination of Italian methods throughout Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 18 But to limit ourselves to Italian sources would be to underestimate the significance of the growing scholarly consensus that thoroughbass is the foundation of eighteenth-century music-making in all its sundry aspects. That is, the story of Italian methods and their dissemination is merely one facet of a larger historical turn taking place in English-language music theory at present.Footnote 19 Heinichen's Der General-Bass is a prime candidate for re-examination within this broader historicizing trend, since his 1728 publication is certainly the most comprehensive and sophisticated thoroughbass treatise ever published, mixing erudition and wit in a manner surpassed only by Heinichen's sharp-tongued friend, Johann Mattheson (1681–1764).Footnote 20 Heinichen's improvisation method not only provides a valuable window onto the pedagogy of one of eighteenth-century Europe's leading theorists, but is also eminently practical, such that one could implement it directly in keyboard instruction today. His four-step method affords an opportunity to combine historiography, theory and performance practice in a mutually supportive and desirable way.

Heinichen's four Steps towards Parnassus are as follows:

1. conjunct bass line with consonant chords

2. disjunct bass line with consonant chords

3. conjunct bass line with dissonant chords

4. disjunct bass line with dissonant chords.

As in any journey, the first step is the hardest. Fortunately, those that follow will require far less explanation. Something that should be noted at the outset, however, and which may surprise the reader, is that Heinichen's method only ever gives a figured bass line, leaving open the question of its realization. On the one hand, the entire treatise can be understood as instruction in how to realize these basses. On the other hand, the fact that Heinichen only gives figured bass lines is in itself a valuable indication of his pedagogical priorities. For Heinichen, the prima fundamenta of preluding involve first and foremost the establishment of a consonant basis upon which dissonances are later added at will.Footnote 21 In this way, the four-step method represents a conceptual scaffolding as much as a practical one. This, I argue, is the underlying value of his method – that it provides a window onto the pedagogical method of a leading baroque composer and theorist. Whether this method manifests itself in improvisation or composition is secondary, for the two are founded on the same principles.

STEP ONE: CONJUNCT BASS LINE WITH CONSONANT CHORDS

Step One is to restrict one's playing to stepwise bass motion with exclusively consonant harmonies. Here the player relies on Heinichen's concept of Ambitus Modi (Example 1), which has two possible meanings. It can refer either to the octave species (arrangement of half-steps and whole steps) for major and minor modes, or to the available closely related keys for modulation (those major and minor keys within one accidental of the main key). Both of these meanings are operative in Heinichen's method, as we shall see. This double function is the reason Heinichen attributes such significance to the Ambitus Modi – it defines both the available key areas and their respective pitch content in a recursive manner. As an aside, it is perhaps worth noting that music theorists throughout history have very often shown a preference for recursion. An example is the traditional predilection for harmonic proportion (6:4:3, where the proportion between the two differences (2:1) is equal to the proportion between the outer terms (6:3)). Recursion is also present in the harmony, wherein an octave and a fifth are each divided harmonically (as in c, e, g, c1). To name one last example, recursive unity is the reason Zarlino reordered the modes as c, d, e, f, g and a – in this form, modal ordering mirrors the natural hexachord. Heinichen's recursive logic is, of course, flawed: neither the seventh degree in the major mode nor the second degree in the minor mode can operate as the tonic of a related key, since the fifth in both cases is diminished.

Example 1 J. D. Heinichen's illustrations of the two meanings of Ambitus Modi, Der General-Bass in der Composition (Dresden: author, 1728), 739 and 899

The first meaning of the Ambitus as octave species is extended into what is undoubtedly the central theoretical conceit of Heinichen's treatise: the Schemata Modorum (Example 2, and see Example 3 for a hypothetical realization in four parts, the standard number of voices in both Heinichen's and J. S. Bach's pedagogy).Footnote 22 The Schemata takes the Ambitus as a collection of bass pitches and adds a consonant harmony – that is, a 5/3 chord or a 6/3 chord – to each bass pitch.Footnote 23 Heinichen considers all other harmonies to be dissonant. The crucial point is that, in a dissonant harmony, one or more pitches must be prepared and resolved down by step, though numerous exceptions existed depending on the contrapuntal situation at hand and the overall stylistic parameters – either church (stylus gravis), chamber or theatre (the modern Italian recitative style). As already mentioned, the orderly classification of such licences, particularly with regard to the theatrical style, was Heinichen's overriding objective as a theorist. His aim was to develop new means of contrapuntal rationalization by which he could extend previous aesthetic boundaries to incorporate recent stylistic developments.

Example 2 Heinichen's Schemata Modorum, or consonant harmonization of the Ambitus modi for major and minor keys, Der General-Bass in der Composition, 746. The figures ‘5 6’ over degrees two and six in major are not to be played consecutively, but represent two separate chordal options. Bracketed figures indicate consonant chords that Heinichen omitted from the Schemata. Bass-degree analysis in this and all following examples is editorial

Example 3 Hypothetical realization of Heinichen's Schemata Modorum from Example 2. Where Heinichen provides two alternative figures I have chosen the option most appropriate to the voice leading of the realization

Yet the Schemata Modorum contains three inconsistencies. First, Heinichen admits one dissonant harmony into the Schema – a 6/4/2 chord – on the descending fourth degree in both major and minor. In this instance, the bass acts as a dissonant passing note (a transitus in Heinichen's terminology) against the upper voices. Second, Heinichen does not include a 6/3 chord on the ascending fourth degree, even though this would be a consonant harmony. Heinichen's rationale, though not stated explicitly, may be his General Rule Four, which states that when the bass of a 6/3 chord with minor sixth (as the third degree in a major mode) ascends by half-step, the second note takes a 5/3 chord. The General Rules and Special Rules provide guidance when accompanying from an unfigured bass in that they help the player infer the correct harmony (always in consultation with the solo voice, Heinichen is sure to emphasize). The General Rules, which derive from the older Klangschrittlehre tradition, operate on exclusively intervallic principles; in contrast, the Special Rules rely on the newer, tonal principle of scale degree, specifically of the bass.Footnote 24 Yet General Rule Four does not apply to the third degree in a minor mode, since the 6/3 chord here has a major sixth and ascends a whole step to degree four. Why did Heinichen not simply allow both 5/3 chords and 6/3 chords on the ascending fourth degree, as he does for the second and sixth degrees in the major mode? Ultimately, his reasoning remains unclear, since his statement that the 6/3 chord and 6/5 chord on the fourth degree represent exceptions clearly does not correspond to standard baroque practice:

Die übrigen Harmonie aber der 4te modi maj. und min. betreffend, so hat sie am allernatürlichsten den ordinairen Accord (Die 6. oder 6/5 seynd ausserordentliche Fälle.).Footnote 25

Regarding the remaining harmonies on the fourth degree in the major and minor modes, this degree most naturally takes the ordinary chord [8/5/3] (the 6/3 chord and 6/5 chord are exceptions).

The third and final inconsistency in the Schemata is the omission of the 5/3 chord on the descending second degree in major. For Heinichen, the second degree may take a 5/3 chord or a 6/3 chord, both ascending and descending. I have added ‘6’ and ‘5’ in brackets at the relevant points in Examples 2, 3 and 5 to account for the second and third of these inconsistencies. This last point leads us to the most important facet of the Schemata – that it is not intended to be played as a chord progression.

This is the main point of difference between Heinichen's Schemata Modorum and the so-called Rule of the Octave (RO; see Example 4), that object of so much attention in recent partimento scholarship.Footnote 26 Heinichen recognizes the features shared between his Schemata and formulations of the RO given by Francesco Gasparini (1661–1727) and Rameau, but he believes his presentation of the topic to be ‘better and more useful’, citing three points.Footnote 27 First, Heinichen places the Semitonium modi (seventh degree) at the beginning of the Schemata in order to avoid the augmented second between the lowered sixth degree and raised seventh degree in the minor mode, and to make his Schemata more concise and clear for beginners. Second, Heinichen states that his Schemata is more useful than Gasparini's and Rameau's RO because the Schemata is made ‘more universal and applicable’ through the omission of ‘special figures’. ‘Special figures’ means anything other than 5/3 chords or 6/3 chords, thus referring to Gasparini and Rameau's use of dissonant harmonies.Footnote 28 As mentioned already, these dissonant special figures contain pitches restricted by their need for resolution. This limits the ordering in which the figures can be employed, as Heinichen emphasizes:

Da hingegen die Schemata beyder Autorum viel speciale Signaturen angeben, die nicht länger gelten, als die Noten fein in der Ordnung marchiren, wie sie hingeschrieben worden.Footnote 29

In contrast, the Schemata [RO] of both authors [Gasparini and Rameau] contain many special figures that are only valid so long as the notes march nicely along in the order in which they were written.

Thus no dissonant chord is totally free in its continuation – the dissonance limits what kind of chord may follow. Instead, Heinichen uses exclusively consonant 5/3 and 6/3 chords, which provides a distinct advantage:

Haben wir unsere Schemata theils durch gänzliche Hinweglassung einiger Ziffern, theils durch die in Modi maj. neben einander stehenden 5. 6. viel universaler und applicabler gemacht, so daß man die natürliche Harmonie in allen Casibus richtig finden kan, die Bass-Claves mögen in der Ordnung wechseln, wie sie wollen.Footnote 30

By completely omitting certain [special] figures, and by allowing for both 5/3 and 6/3 chords [on degrees two and six] in the major mode, we have made our Schemata much more universal and practicable, such that one can find the natural harmony correctly in all cases, regardless of whether the bass notes are placed in a different order.

This is the central difference between the Schemata and the RO: with the exception of the descending fourth degree, all pitches of the Schemata may be rearranged freely. That is, unlike the RO, it is not limited to being played as a chord progression. In Heinichen's method of improvising a prelude, one of the player's most important tasks, as we shall see, is to be aware of whether the chord being played at the moment contains restricted pitches.

Example 4 David Kellner's Schemata (actually the Rule of the Octave) with hypothetical realization. Treulicher Unterricht im General-Bass, second edition (Hamburg: Christian Herold, 1737), 31 and 34. Annotations refer to Heinichen's theory of dissonance treatment

Heinichen's third point of difference with the RO is that, unlike the versions offered by Gasparini and Rameau, the Schemata omits the chord of the major sixth from the descending sixth degree in a major mode (compare the chords indicated by the pointing hands in Examples 3 and 4). Heinichen says that this chord is confusing to the beginner because the accidental it employs does not belong to the main mode:

Denn wenn z. E. unsere Autores im g dur die aus der 8ve in die 5te herabsteigende Claves also beziffern, {[5,] 6, ♯6, ♯ [over bass notes] g, fis, e, d} so ist dieses schon eine halbe Cadenz und Ausschweiffung in das D. dur, womit das g dur nichts zu thun hat. Zugeschweigen, daß wenn man es auch unter dem g dur passieren liesse, so wäre es doch ein special Casus, der nicht länger gilt, als diese Noten just so in der Ordnung bleiben.Footnote 31

When, for example, our authors [Gasparini and Rameau] figure the first scale degree descending by step to the fifth degree in G major {[bass notes] g, f♯, e, d} with {[figures][5,] 6, ♯6, ♯}, this is already a half cadence and tonicization of D major, which has nothing to do with G major, to say nothing of the fact that if one were to allow this in G major, it would represent a special case that only applies so long as the [bass] notes remain in exactly the same ordering.

Thus tonal consistency and freedom of progression are of paramount importance in Heinichen's pedagogy. That he considered the preservation of a unified, diatonic Ambitus Modorum important enough to exclude ficta from his Schemata is an important marker in the emergence of the modern tonal system, a point already emphasized by Ludwig Holtmeier in relationship to the RO.Footnote 32

Since the RO has received so much attention in recent literature, and since the Schemata is so central to Heinichen's method, it is worth treating Heinichen's critique of the RO in greater detail. To do so, we will examine David Kellner's previously mentioned Treulicher Unterricht im General-Bass. Although Kellner's 1732 tract is largely a digest of Heinichen's 1728 treatise, Kellner chooses not to adopt Heinichen's Schemata. Instead, he offers the RO with the same figuring as Rameau (without citation), though he still calls it the Schemata (Example 4). Given this similarity, a comparison of Kellner's RO and Heinichen's Schemata will help to illustrate Heinichen's critique of the RO. The bracketed editorial annotations in Example 4 refer to Heinichen's understanding of dissonance as explicated elsewhere in his treatise.Footnote 33 In a nutshell, Heinichen only recognizes two types of dissonance: syncopatio (suspensions) and transitus (passing and neighbour notes), though both categories admit many licences. Kellner's RO uses three ‘special’ dissonant figures – 6/4/3, 6/5 and 6/4/2 – which we shall examine in turn in the light of Heinichen's theories.

Heinichen would define the 6/4/3 chord in all cases as a 4-irregularis. This fourth is deemed irregular because it is not treated in the normal fashion (prepared and resolved down by step). But in fact the name irregularis is misleading, because there is nothing irregular about this particular contrapuntal event. The fourth above the bass is merely sustained as an upper-voice pedal point against a double transitus in the other voices, which are marked in black editorially, a point Heinichen emphasizes.Footnote 34 Six such cases are shown in Example 4. The second special figure in Kellner's RO is the 6/5 chord, which occurs in two contrapuntal contexts. On the ascending fourth degree, there is a consonant perfect fifth against the bass, which Heinichen cautions must be treated as a dissonance because of the simultaneous presence of the sixth above the bass:

Diese resolutio indispensabilis aber ist wohl das allersicherste Kennzeichen einer wahren Dissonanz: dahero der gemeine Einwurff, welchen man sonst auch der unschuldigen 4te zu machen pfleget: daß nehmlich die 5ta perfecta bey der 6te sich gleichfals als eine Dissonanz aufführe, und doch eine Consonanz sey; gar nichts darwider beweiset. Denn wer zwinget doch die 5t. perfect dazu, wenn sie sich freywillig in die Sclaverey neben der 6te begiebet? sie kan ja vor sich alleine gegen den Bass-Clavem. iederzeit ohne Fessel, als eine Consonanz erscheinen, und brauchet sodenn keiner resolution: Die 5ta min. hingegen darff sich so wenig ohne darauf folgende resolution gebrauchen lassen, als andere unstreitige Dissonantien der 2de, 7me, 9ne &c. Wahr ist es, daß sie nicht iederzeit muß præpariret werden, oder vorhero liegen; allein das machet sie zu keiner Consonanz, weil solches auch der 4te und 7me gemein ist, welche manche doch beide vor unstreitige Dissonantien halten.Footnote 35

The necessity of resolution is certainly the surest indicator of a true dissonance. Thus arises the common accusation (which one usually makes to the innocent fourth) that the perfect fifth next to the sixth [in a 6/5 chord] behaves as a dissonance, and yet it is a consonance – nothing can disprove this. For who forces the perfect fifth to proceed freely into slavery next to the sixth? The perfect fifth can appear at any time alone, unchained, as a consonance against the bass, requiring no resolution. The diminished fifth, however, may no less be used without a subsequent resolution than any of the other indisputable dissonances of the second, seventh, ninth, etc. It is true that the diminished fifth must not always be prepared, or have already sounded, but that alone does not make it into a consonance, because this [optional preparation] is true of the fourth and seventh as well.

In contrast, the fifth in the 6/5 chord on the ascending seventh degree is already a dissonant diminished fifth, and therefore already in need of resolution, even without the sixth in its 6/5 chord. Regardless of the quality of the fifth, Heinichen refers to the restricted pitch in this special chord as a 5-syncopatio because it is made to act like a suspension, even when it is consonant. Third and finally, I have already mentioned that the 6/4/2 chord on the descending fourth degree, which also features in Heinichen's Schemata, is a bass transitus.Footnote 36 The key point is that these dissonant harmonies – 6/4/3, 6/5 and 6/4/2 – contain pitches that are restricted in their motion, thus limiting the improviser's freedom to progress from any chord in the Schemata to any other. Step One in Heinichen's method avoids this limitation by omitting all special figures (except 6/4/2).

Example 5 shows Heinichen's illustration of Step One – a conjunct bass line with exclusively consonant chords. The novice improviser should select any key at will; Heinichen arbitrarily chooses F major. Next, one arranges the Schemata of all the neighbouring keys one after another. This (and Step Three below) are the only instances in Heinichen's entire treatise where the Schemata is conceived as a progression. As already noted, the primary advantage of the Schemata over the RO in the context of improvising is that it allows for the free ordering of notes, as we shall see in Step Two. But first we must briefly discuss the selection and ordering of keys.

Example 5 Step One: conjunct bass line with consonant chords. ‘The first rudiments’ of a prelude consisting of the Schemata of each closely related key, starting in F major. Heinichen, Der General-Bass in der Composition, 903–904. The black noteheads, which are original, indicate either restricted transitus notes with a 6/4/2 chord that must descend by step or the chromatically flexible sixth and seventh degrees in minor

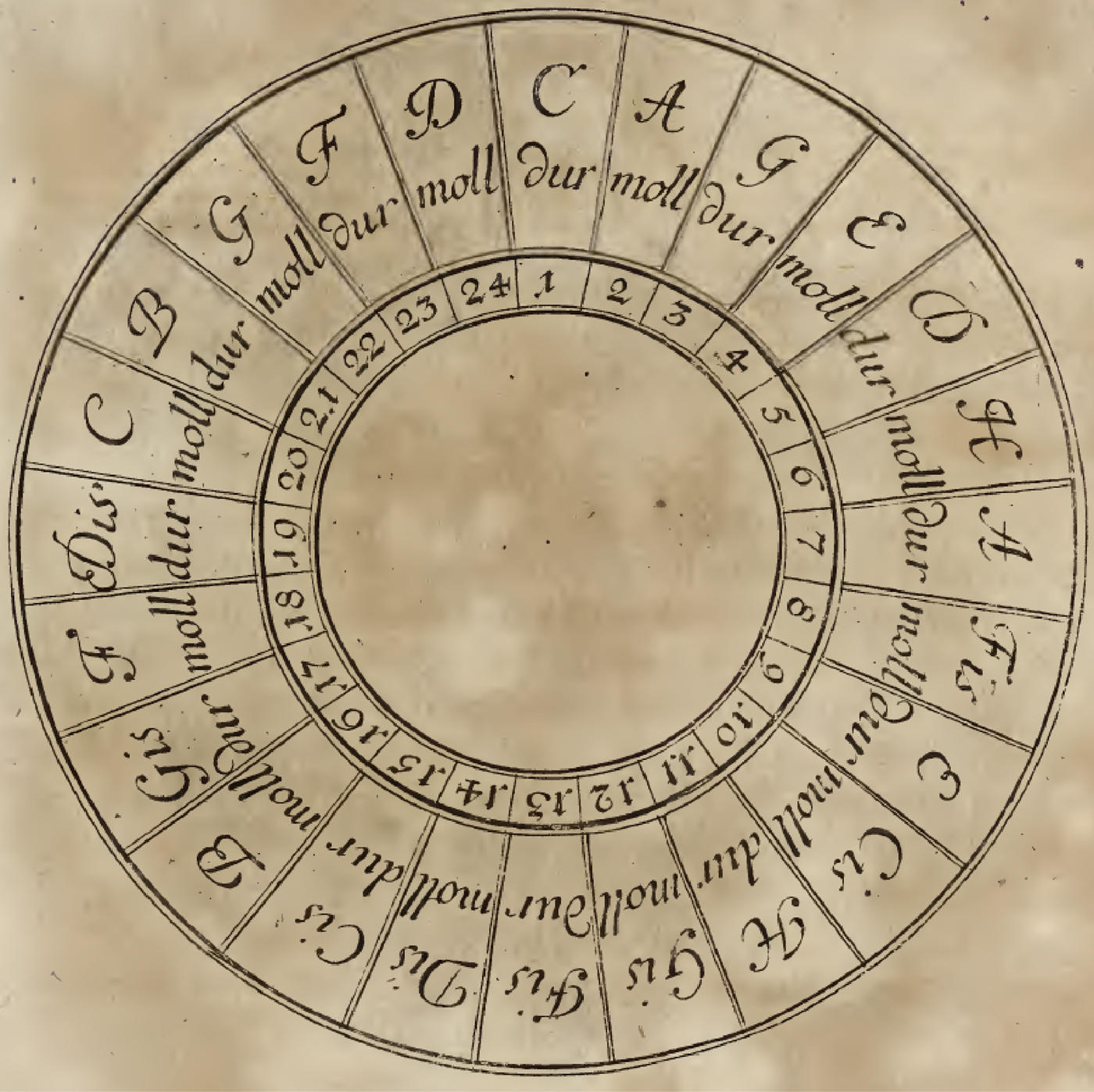

Key selection is easy enough – there are always five available neighbouring keys, each a single accidental removed from the main one. To assist the student in ordering the keys properly, Heinichen offers his famous circle (Figure 1).Footnote 37 Unlike the circle of fifths, Heinichen's circle proceeds by minor third and whole step, always alternating major and minor keys. Beginning with F major, we find the available five neighbouring keys three spaces clockwise (D minor, C major and A minor) and two spaces counterclockwise (G minor and B flat major). One is permitted to modulate to adjacent keys or to skip over a maximum of one key at a time. This second prescription seems to be intended merely for beginners, since it eliminates the option of modulating directly from F major to the neighbouring key of A minor (or the reverse) – a fairly common key relationship in the Baroque. Though Heinichen does not mention any particular ordering as the preferred one, the sequence he chooses in Example 5 – F major, C major, A minor, D minor, G minor, B flat major, F major – is surely one of the most conventional, since it begins with the dominant (C major) and ends with the subdominant (B flat major). In fact, if one begins with the dominant and touches upon all five neighbouring keys once, there is no other modulatory path available than the one in Example 5, given Heinichen's restriction of not skipping more than one key at a time. Thus, Heinichen's circle guarantees that the tonal plan of the improvisation corresponds closely with standard baroque practice. With the conjunct, consonant foundation of Step One in place, we can now proceed with the subsequent steps. Taken together, the goal of the remaining steps is to alleviate the two faults (‘Haupt-Fehler’) in Example 5: the absence of leaps and the absence of dissonance.

Figure 1 J. D. Heinichen's musical circle, Der General-Bass in der Composition (Dresden, 1728), 837. The suffixes ‘-s’ and ‘-es’ mean ‘sharp’ and ‘flat’ respectively, while ‘moll’ and ‘dur’ mean ‘minor’ and ‘major’

STEP TWO: DISJUNCT BASS LINE WITH CONSONANT CHORDS

The next step is to allow leaps in the bass while maintaining the exclusively consonant harmonies. Heinichen's illustration of this is shown in Example 6. To save space, he only demonstrates two key areas – F major and D minor – but it is assumed that the prelude would include all the keys shown in Example 5. Since the Schemata is restricted to consonant harmonies, one is free to leap from any bass degree to any other, remaining in a given key as long as one wishes.Footnote 38 This freedom of progression goes against the oft-repeated adage in historical scholarship today that a 6/3 chord must be continued stepwise. For instance, Holtmeier writes that

The triad [5/3] represents perfect consonance, the persistent ‘cadential’ sonority of repose, the initial and goal chord of a harmonic progression. By contrast, the chord of the sixth [6/3] represents imperfect consonance, the sonority of motion, which demands a stepwise continuation.Footnote 39

Surely Holtmeier is correct regarding the tendency for 5/3 chords to begin and end phrases and for 6/3 chords to be used in the middle of phrases. However, in Heinichen's theory, a 6/3 chord by no means ‘demands’ stepwise continuation. Of the forty instances of 6/3 chords in Example 6, sixty-three per cent move by step, whereas thirty-seven per cent move by leap.Footnote 40 Instead it would be more accurate to formulate the difference between 5/3 and 6/3 thus: all consonant harmonies may leap, but a 5/3 chord tends not to proceed by half-step in the bass to another 5/3 chord (though it may proceed by whole step). Indeed, this is how Heinichen seems to conceive of the difference between 5/3 and 6/3. He considers consecutive 5/3 chords on bass notes a half-step apart to be ‘unnatural’ and characteristic of an older style. By contrast, he writes, the moderne Gusto usually assigns a 6/3 chord on one or both notes located a half-step apart, though Heinichen identifies one exception apparently used especially often by Italians (essentially a minor-mode ‘deceptive’ cadence, or what would be roman numerals V–VI):

In antiquen Sachen findet man folgende unnatürliche Säze zweyer neben einander liegenden halben Tone alle Augenblick (5/3, 5/3, 5/3, 5/3 [these figures placed over the bass notes:] e f f e). Der moderne Gusto aber richtet sie besser nach seinen modis ein, und vermischet sie auff unterschiedene Arth mit der 6te, wie folgende 3. ersten Exempel zeigen. Das 4te Exempel aber kommet schon seltener vor, ob gleich der antique Gusto durch eine über die erste Note gesezte 3. maj. corrigiret wird.Footnote 41

In ancient works one constantly finds the following unnatural progression containing two adjacent semitones ([figures] 5/3, 5/3, 5/3, 5/3 [over the bass notes:] E F F E). But the modern style adapts this [progression] better according to its key and mixes in a 6/3 chord, as the first three of the following examples show [in Example 7]. The fourth example, however, occurs less often, even though the ancient style is corrected via the addition of a major third over the first note.

Example 6 Step Two: disjunct bass line with consonant chords. Heinichen, Der General-Bass in der Composition, 905–906. Black noteheads indicate restricted fourth degrees that must continue down by step. ‘5 6’ indicates that a given degree may take either 5/3 or 6/3. Other annotations are editorial

Example 7 Heinichen's examples of how the modern style requires a sixth over one or both bass notes a semitone apart. Der General-Bass in der Composition, 742, note k

However, the reader who is already familiar with Heinichen's treatise may point, for example, to Heinichen's Special Rule Five as evidence to the contrary – that 6/3 chords do indeed demand stepwise continuation. Special Rule Five states that the second degree in the major mode may take 5/3 or 6/3, depending on the context:

Wegen des modi maj. aber ist besonders zu mercken, daß weil seine 2da modi allerdings eine 5te perfect. in ambitu hat, so stehet auch frey, ob man über besagter 2da modi die 5te oder die 6te gebrauchen will. Natürlicher lautet die 6. wenn man gradatim in die 3e auf oder rückwerts gehet, wie folgende 2. ersten Exempel ausweisen. Kömt aber die 2da modi mitten im Sprunge zu stehen, so fället die 5te natürlicher aus, wie folgende 2. lezten Exempel zeigen.Footnote 42

In the major mode it should especially be noted that, since the second degree has a perfect fifth in its Ambitus, one has the freedom to use either the fifth or the sixth. The sixth sounds more natural if one ascends to or descends from the third degree by step, as the following first two examples show [in Example 8]. But if the second degree occurs amidst a leap, then the fifth is more natural, as the last two examples show.

Indeed, this does reveal a preference for a 6/3 chord on the second degree when ascending stepwise to the third degree. But, as with all the Special Rules, this advice is intended to aid in determining the appropriate chords for an unfigured bass. This is why the Special Rules can be framed in terms of both approach to and continuation of a given note. In contrast, in improvisation, it would be useless to play a chord and then use the previous bass note to decide which chord one should have played. No: the conceptual framework must accommodate the fact that the improviser's attention is directed forwards in time. Heinichen, cognisant of this, frames his improvisation method in terms of ‘how to decide which chord should follow’.

Example 8 Heinichen's four illustrations of how the second degree takes a sixth in a stepwise context, but a fifth in a leaping context. Der General-Bass in der Composition, 743

Thus far we have seen how, in Step Two, the player is exempt from any limitation regarding the progression of the bass, so long as all harmonies are derived from the Schemata, which ensures they will be consonant (except the 6/4/2 chord on the descending fourth degree). This freedom would seem to imply that all progressions would appear with equal frequency, but this is not the case. Example 9 provides a tally of all two-note progressions found in Example 6. The vertical y-axis shows the first note, while the horizontal x-axis shows its destination. The intersection of two degrees gives the frequency of their progression.Footnote 43 Of course, there are dangers in drawing broad conclusions from such a small data set (n = 120), but one can nevertheless infer some general patterns beyond those intervallic sequences that are plainly evident without statistical analysis (see annotations to Example 6). Examining the summed table in Example 9, one will not be surprised to see that bass motion involving ![]() $\hat5$–

$\hat5$–![]() $\hat1$ predominates (eleven instances), followed closely by

$\hat1$ predominates (eleven instances), followed closely by ![]() $\hat4$–

$\hat4$–![]() $\hat5$ (ten instances). The next most common progressions are

$\hat5$ (ten instances). The next most common progressions are ![]() $\hat5$–

$\hat5$–![]() $\hat3$ (nine instances), which is a common means of avoiding a

$\hat3$ (nine instances), which is a common means of avoiding a ![]() $\hat5$–

$\hat5$–![]() $\hat1$ cadence in the Baroque, and so on to the less frequent progressions. The gaps in Example 9 (that is, those progressions that never occur) are also revealing. For instance,

$\hat1$ cadence in the Baroque, and so on to the less frequent progressions. The gaps in Example 9 (that is, those progressions that never occur) are also revealing. For instance, ![]() $\hat7$ is only ever approached by

$\hat7$ is only ever approached by ![]() $\hat1$ or

$\hat1$ or ![]() $\hat2$; and

$\hat2$; and ![]() $\hat7$ then only moves to

$\hat7$ then only moves to ![]() $\hat1$ or

$\hat1$ or ![]() $\hat5$. Finally, one could observe even without doing a tally that Heinichen prefers motion by second and third (that is, by smaller intervals). Yet, as stated already, one should be cautious about reading too much into such a brief exercise as Example 6. In closing, it should be noted that Heinichen makes no mention of how to handle the transitions between key areas. Judging by Example 6, it would appear one simply makes a cadence (with bass

$\hat5$. Finally, one could observe even without doing a tally that Heinichen prefers motion by second and third (that is, by smaller intervals). Yet, as stated already, one should be cautious about reading too much into such a brief exercise as Example 6. In closing, it should be noted that Heinichen makes no mention of how to handle the transitions between key areas. Judging by Example 6, it would appear one simply makes a cadence (with bass ![]() $\hat5$–

$\hat5$–![]() $\hat1$) and then proceeds to the next key. Having introduced leaps in Step Two, Heinichen now retreats back to the conjunct motion of the Schemata in order to make the introduction of dissonance pedagogically more manageable in Step Three.

$\hat1$) and then proceeds to the next key. Having introduced leaps in Step Two, Heinichen now retreats back to the conjunct motion of the Schemata in order to make the introduction of dissonance pedagogically more manageable in Step Three.

Example 9 Frequency of progressions from a given bass degree (y-axis) to another (x-axis) in Example 6. Arrows next to degrees six and seven refer to chromatic alterations in the minor mode

STEP THREE: CONJUNCT BASS LINE WITH DISSONANT CHORDS

The Haupt-Principium of employing dissonance is

Daß bey natürlich fortgehender Harmonie, niemahls weder ein ordinairer, noch extraordinairer Accord könne angeschlagen werden, davon nicht wenigstens eine einzige Stimme (wo nicht mehr) in dem folgenden Saze könte liegen bleiben i. e. legaliter binden, und nachmahls resolviren, ohne den Ambitum modi in geringsten zu beleidigen.Footnote 44

That in a naturally proceeding harmony, no ordinary [8/5/3] or extra-ordinary [dissonant] chord may be used if at least one voice (if not more) cannot be tied over, that is, properly suspended, into the following chord and afterwards resolved without in any way infringing upon the Ambitum modi.

Put another way, ‘Never play a chord that does not allow the suspension of at least one note into the following chord’. In context, this is achieved in one of the following ways:Footnote 45

1. 6 is suspended by 7

2. the ‘ordinary chord’ (8/5/3) is suspended with 4, 9 or both

3. a bass note descending by step to a 6/3 chord can be syncopated by means of a 6/4/2

4. the diminished fifth is added to the 6/3 chord on the seventh degree

5. the 9 is added to the 6 on the third degree in D minor.

We could rephrase these rules to say that any upper-voice consonance may be suspended as the dissonance a step above it: 3 by 4, 6 by 7 and 8 by 9, plus the bass may be suspended by the note a second above (by 2). Or put even more simply: any time a voice descends by step it may be delayed to make a syncopatio. Note, however, that suspending 5 as 6 does not result in a dissonant syncopatio, since the latter interval is consonant. (As mentioned already, the 5 – or any other consonance – may only be made to act as a syncopatio dissonance by the addition of the note one step above it in the same chord: 4/3, 6/5 or, exceptionally, 9/8.) Through the addition of such dissonances to our consonant framework, the Ambitus is not ‘offended’ in the least, but, rather, ‘made more harmonic’.Footnote 46 All the dissonances are ‘nothing other than pure suspensions of the following ordinary consonances’.Footnote 47 Example 10 shows Heinichen's two models of the above principle applied to the Schemata of F major and D minor. The rhythmic structure of the suspensions necessitates the introduction of a time signature, which is to be understood flexibly (more on this in Step Four). Example 11 provides a hypothetical realization of Example 10. For convenience, ties in Example 11 identify the location of syncopatio dissonances (recall that the bass too may be suspended). Considering Examples 10 and 11, it is unclear why Heinichen singles out the fifth point in the above list regarding the addition of a ninth to the 6/3 chord in minor, for he only does this once (marked by the pointing hand in Examples 10 and 11).

Example 10 Step Three: conjunct bass line with dissonant chords. Heinichen, Der General-Bass in der Composition, 907–909

Example 11 Hypothetical realization of Example 10. Arrows identify the only consonant harmonies. The boxes indicate 6/4 chords with unprepared sixths. The pointing hand marks the only 9/6 chord over the third degree in minor

Curiously, there are two chords in Examples 10b and 11b that neither contain a suspension nor form a resolution of the same. That is, they do not adhere, strictly speaking, to Heinichen's above Haupt-Principium, even though in both cases it would have been possible to suspend a pitch as a syncopatio from the previous chord. These two chords are marked with arrows. Two other voice-leading anomalies deserve mention. These are boxed in Example 11b. In both instances, Heinichen approaches a 6/4 chord in such a way that the 6 cannot be prepared, resulting in quite awkward voice leading. It seems unlikely that Heinichen would expect the player to improvise a solution to such a complex problem, though this could be the case. Regardless, the main point Heinichen wishes to make in giving two models for Step Three is that the Haupt-Principium may be applied to the Schemata in various ways.Footnote 48 That is, the improviser may introduce as many or as few dissonances as desired, so long as they are resolved properly. Nevertheless, as Heinichen is keen to point out, no prelude is restricted exclusively to stepwise motion in the bass. One step remains in our pedagogical and conceptual journey: the simultaneous use of dissonance and leaps.

STEP FOUR: DISJUNCT BASS LINE WITH DISSONANT CHORDS

Heinichen achieves the final step in his method by adding syncopatio dissonances to the same bass line used in Step Two (Example 6).Footnote 49 To conserve space, his model of Step Four (only a figured bass) is shown here in combination with an editorial solution in Example 12. As in Step Three, the student-improviser is to apply this strategy to all key areas in Step One (Example 2), resulting in an ‘extensive harmonic prelude’.Footnote 50 As before, one is free to add more or less dissonance. And Heinichen even mentions that one may return to previous key areas in order to make the prelude as long as desired. Two voice-leading details deserve mention. First, for greater clarity, I have marked with arrows those instances where a dissonance resolves over a change of bass note. That is, while the bass moves consistently in semibreves, some of the syncopatio resolutions occur at the minim, while others are suspended for two or more bars. Secondly, four bars from the end (marked by a pointing hand) one is required to extend the number of voices to five in order to prepare the following seventh. Although Heinichen makes no mention of this, he allows for it elsewhere in his treatise.Footnote 51

Example 12 Step Four: disjunct bass line with dissonant chords. Heinichen, Der General-Bass in der Composition, 910–911. A hypothetical realization is provided. Arrows indicate syncopatio dissonances whose resolution is delayed until the following bar. The pointing hand indicates an instance where five voices are necessary

According to Heinichen, those who are more practised should regard the bass notes of Example 12 merely as the ‘foundation of their prelude’:

Denenjenigen aber, die in der Music etwas mehr geübet, und sich im praeludiren auch ausser dem Alla breve wollen hören lassen, kan man noch diesen Rath ertheilen, daß sie die verwechselten Bass-Noten der zusammen gestossenen Schematum eines Haupt-Modi, nur als das blosse Fundament ihres praeludii ansehen, und darüber mit Verlängerung und Verkürzung gedachter Bass-Noten, allerhand Variationes und Fantasien nach eigenen Einfällen erdencken können, ohne die geringste Gefahr, sich weder in denen Tonen zu verliehren, noch wieder den Ambitum Modi zu pecciren.Footnote 52

But those who are more practised in music and who would like to hear something other than an alla breve in preluding can be advised to regard the mixed-up bass notes of the linked Schemata of a main key as a mere foundation for their prelude, above which they can invent all kinds of variations and fantasies as desired while also lengthening and shortening the bass notes, without the slightest danger of either getting lost in the keys or offending the Ambitus.

Curiously, Heinichen advises that when playing such variations, one can omit the dissonances, relying instead on the Schemata in its original, consonant form as given in Example 6.Footnote 53 Although he gives no models, this statement implies that ‘variation and fantasies’ refers to more or less single-line passagework, which is easier to construct within a purely consonant framework. And finally, Heinichen concludes his discussion of improvised preluding with what is undoubtedly the most important statement of the whole method, and perhaps of his entire treatise:

Wer nun unsern ganzen praeludien-Discurs von §. 24. biß hieher vernünfftig überleget, der wird finden, daß dieses eine überaus vortheilhafftige Methode sey, einen Anfänger nicht allein zum praeludiren, sondern auch zum componiren selbst glücklich anzuführen.Footnote 54

Whoever has fairly considered our whole discourse on preluding from §. 24 to this point [that is, Steps One to Four] will find that this is an extremely advantageous method of successfully instructing a beginner not only in preluding, but in composition itself.

It would be easy to overlook the significance of this statement. Indeed, for a treatise entitled ‘Thoroughbass in Composition’, it is somewhat disappointing that Heinichen never provides direct instruction in how to compose a piece. Only this once, after extensive discussion of how to improvise a prelude, does Heinichen reveal that the improvisation method is actually how he begins instruction in composition as well.

Having reached the final step in our journey, the reader is surely wondering: does Example 12 represent a true musical Parnassus? Certainly not as it currently stands, given such a modest, unornamented realization. Yet Heinichen never claimed that his four-step method would carry us to the summit of musical knowledge. Indeed, to be able to improvise a prelude of even modest calibre requires prolonged, extensive training – in Heinichen's words, ‘these Steps to Parnassus cannot be scaled in a year’. So what have we achieved? Much that contributes to our understanding of early eighteenth-century music, I would argue. We have learned that there are only two modes – major and minor (the Ambitus Modi). We have learned how to determine related key areas and arrange these in a suitable order. We have learned how to distinguish between consonant (5/3 and 6/3) and dissonant harmonies (everything else). We have learned which consonant harmonies are associated with which bass degrees (the Schemata Modorum). We have learned that dissonant harmonies contain one or more transitus or syncopatio pitches that are restricted in their motion. We have learned that dissonance is essential to a composition, but that its need for resolution requires special contrapuntal attention. And most importantly, I believe, we have learned that thoroughbass is the basic theoretical framework for conceptualizing music in this period. All this, according to Heinichen, constitutes the prima fundamenta, not only of improvisation, but of composition as well. It is as if improvisation and composition were two brothers apprenticed to the same master. After taking their first steps together, the journeymen eventually part ways in their journey towards Parnassus. Yet whenever their paths cross, the brothers embrace and, eager to learn from one another, exchange stories.