Christoph Gluck (1714–1787) is hailed as the ‘first truly international opera composer’.Footnote 1 His musico-geographical biography alone is enough to justify this label, for Gluck was ‘born in Germany, raised in Bohemia, learned his trade in Milan, absorbed lessons in simplicity from Handel in London, collaborated with like-minded reformers in Vienna, and created his finest works for Paris’.Footnote 2 As Eve Barsham has noted, the ever-widening area in which Gluck's Orfeo (and his Orphée) was performed in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, extending ‘from Spain to Stockholm and from Dublin to Budapest’, is remarkable.Footnote 3 Gluck is also considered international in linguistic terms: he spoke Czech, possibly as a native speaker, though his primary language was German; he was also conversant with, if not fully fluent in, French and Italian (the principal languages of his librettos), and he displayed a solid grasp of the prosody of both.Footnote 4 At the same time that Gluck championed the cause of French-language opera, he claimed, paradoxically, to be seeking a musical language ‘propre à toutes les Nations’ (fit for all nations) that would ‘faire disparoître la ridicule distinction des musiques nationales’ (banish the ridiculous distinctions between national musical styles).Footnote 5 This of course made particular reference to the ongoing debate over the respective merits of opera in Italian and opera in French; and, as critics have observed, Gluck's claim is somewhat misleading, particularly in light of the lengths to which he went in order to transform his Italian Orfeo into a French Orphée. Nonetheless, his allusion to an international style, combined with his international profile, suggests that he may have aspired to something more far-reaching.Footnote 6

Yet the scope of Gluck's internationalism has been consistently understood in strictly European terms. Here I would like to suggest that Gluck's international profile stretched beyond Europe even during his lifetime, and specifically into the French colonial Caribbean, where his work reached both the Greater and Lesser Antilles (see Figure 1). Most significantly, three of Gluck's serious French operas that had premiered in Paris in the 1770s were performed in the 1780s in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), in the Greater Antilles. These were Iphigénie en Aulide (premiered at the Académie Royale de Musique on 19 April 1774), Orphée et Eurydice (premiered in Iphigénie’s wake at the Académie Royale on 2 August 1774)Footnote 7 and Iphigénie en Tauride (premiered at the Académie Royale on 18 May 1779).Footnote 8 These three works form the focus of the present article. Orphée et Eurydice and Iphigénie en Aulide were performed in both Cap-Français (known as Le Cap, and in the modern day as Cap-Haïtien), the island's economic capital in the north and principal port of the French Antilles, and in the newer town of Port-au-Prince in the southwest and the island's administrative capital from 1770. We know of only one performance of Iphigénie en Tauride, which was in Cap-Français. Intriguingly, however, Iphigénie en Tauride reached the audience in Port-au-Prince rather more obliquely, in the form of its operatic parody, Les Rêveries renouvellées des Grecs. Meanwhile, Orphée et Eurydice was performed on at least one occasion during the 1780s in the French colony of Martinique, in the Lesser Antilles. Its one documented performance there was in the town of Saint-Pierre, whose impressive and elegant theatre was described by a Danish eyewitness as surpassing its European equivalents in grandeur and good taste (‘qui surpasse pour la grandeur & le goût les bâtimens en ce genre les plus renommés en Europe’).Footnote 9

Figure 1 The Greater and Lesser Antilles during the late eighteenth century

The primary aim of this article is to establish that three of Gluck's Paris operas were produced in the French Caribbean in the 1780s and to present what can be uncovered about the performances of each of them. The principal source of information about theatre in Saint-Domingue is to be found in the local newspapers, the Affiches Américaines (AA) and the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines (SAA), and their many variants, on which the researcher must heavily rely;Footnote 10 this information is supplemented here by additional sources on the few occasions that these are extant. The second aim of the article is to insist on the significance of these performances of serious opera in the context of the Saint-Dominguan repertoire, which, though diverse, excluded entirely the tragédies en musique of Lully and Rameau, preferring instead the opéras comiques and lighter musical works by figures such as Monsigny (including On ne s'avise jamais de tout, La Belle Arsène and Le Déserteur) and especially Grétry (Isabelle et Gertrude, Silvain, Zémire et Azor, La Fausse magie and others). Each of the three operas – and their different performance locations – tells a slightly different story about how Gluck fared in the French colonial Caribbean, and they are examined here in turn so as to reveal these differences (and to enable individuals with a particular interest in a particular opera to find the relevant information). The article is thus intended first as a contribution to Gluck scholarship, but it also seeks to set out some ways in which the rich but still under-researched theatrical tradition of the French Caribbean might be opened up further.Footnote 11

THEATRE IN THE FRENCH COLONIAL CARIBBEAN

Despite the considerable financial and practical difficulties involved in setting up and, especially, maintaining theatres in the Caribbean during this period, theatre enjoyed remarkable success in the French colonial Antilles during the late eighteenth century, right up until the slave revolts of 1791 (with occasional performances after this), and Saint-Domingue boasted the most vibrant theatrical tradition of any of the Caribbean colonies. In addition to more sporadic and less well-documented theatrical endeavours in other smaller towns (Léogane, Les Cayes, Saint-Marc and Jérémie), the French part of the island enjoyed two principal theatrical centres in the 1770s and 1780s, with separate troupes and audiences, each with custom-made buildings: the first in Cap-Français and the second in Port-au-Prince. In its entry on Cap-Français and the colonies, the Almanach général de tous les spectacles de Paris et des provinces pour l'année 1791 highlights the widespread enthusiasm in the French Caribbean for theatre at the same time that it calls into question its theatrical standards:

On n'est pas difficile dans nos Colonies en fait de spectacle; et les habitans du Cap sont tellement avides de comédie, que, pourvu qu'ils aient des comédiens quelconques sous les yeux, ils leur font grace du reste, parce qu'il faut se contenter de ce que l'on a, faute de mieux.Footnote 12

When it comes to theatre, they are not picky in the colonies, and the inhabitants of Le Cap are so hungry for drama that as long as they have some actors in front of them, they forgive them everything else, because they have to make do with what they've got in the absence of anything better.

While it is true that, unsurprisingly, the colonies struggled to attract the most successful performers from France, it would be wrong to assume that theatrical standards were always poor in the French Caribbean at this time. Some talented actors from Europe did come to the West Indies, and the islands also developed talent of their own. Indeed, it was not unusual for European visitors to express their surprise at how good the performances were. Alfred de Laujon, for instance, who visited the theatre in Port-au-Prince in the 1780s, reported ‘j'entendis plusieurs voix qui me surprirent et je ne trouvai pas que la pièce fût mal représentée’ (I heard several voices that surprised me and I thought the work wasn't badly performed).Footnote 13

In the French Caribbean, opera and spoken drama were performed in the same theatre, by the same troupe. While some individuals were recognized as specialists in a particular theatrical genre, they were usually expected to participate in a wide variety of genres, and people who might in France have been recognized as opera singers were here given the more generic label of actor. This conflation of resources for spoken drama and opera may account in part for the priority given to opéra comique, with its mixture of spoken dialogue and sung arias. A performance was often advertised in the press as being ‘orné de tout son spectacle’ (decorated with all its spectacle) – a generic formulation that was vague enough to indicate anything from the use of costumes and stage sets to the inclusion of all the danced elements. A typical evening at the theatre in Saint-Domingue comprised a double bill, with a musical interlude in the middle and a dance at the end, and similarities with previous productions of the same works in France were emphasized. At their peak, troupes in Port-au-Prince and Le Cap gave up to three regular subscription performances per week plus occasional, though not infrequent, benefit performances organized by, and for the financial benefit of, one of the troupe members.Footnote 14

Theatre troupes were usually engaged by the season, and were comprised mostly of French performers who had moved to Saint-Domingue or who were committed to staying there for several years (itinerant troupes or individuals also visited occasionally). The great chronicler of life in late eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue, Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry, tells us in his Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l'isle Saint-Domingue that the troupe in Port-au-Prince comprised sixteen actors (eight men and eight women) and an orchestra of eleven musicians.Footnote 15 By way of contrast, Patricia Howard speculates that the orchestra for the Paris premiere of Orphée consisted of twenty-eight violins, six violas, twelve cellos, five double basses, two flutes, four oboes, two clarinets, four bassoons, two horns, three trumpets, three trombones and timpani, plus a harp (a far larger orchestra than was required for the earlier, Italian version of the work and a slightly larger orchestra than is called for in the 1774 score).Footnote 16 Clearly, Saint-Domingue could not aspire to reproduce anything like the scale of the Paris performances, though additional performers were brought in on an ad hoc basis. The acting troupe in Le Cap typically comprised twenty actors (twelve men and eight women), while the number of musicians is not given.Footnote 17 Although Moreau de Saint-Méry makes no mention of this fact, slaves made a significant contribution to the theatre orchestras in Saint-Domingue. Indeed, Bernard Camier has calculated that of the 130 or so known instrumentalists in Saint-Domingue, approximately 70 were slaves, the great majority of them violinists.Footnote 18 It is significant that this information comes to us not from any documents detailing local theatre productions, but rather from advertisements for the sale of slaves (slaves with a special talent could command higher prices) and for the return of runaway slaves.

With respect to the audience, Moreau de Saint-Méry notes that in the period that concerns us, the theatre in Port-au-Prince could accommodate approximately 750 spectators, while the theatre in Le Cap had a capacity of 1,500.Footnote 19 The theatre audience was quite diverse and included French-born colonials, members of the French military, whites born on the island (known as créoles) and a modest but significant number of free people of colour – a group that included a small number of black people as well as people of mixed race. Segregation was a feature of the theatres in Saint-Domingue (as in Martinique), all of which permitted a disproportionately small number of free people of colour to attend performances: in 1780s Port-au-Prince, all the free people of colour sat together in fifteen second-tier boxes (seven on either side of the auditorium and one at the back), while in Le Cap, the people of colour sat in the upper boxes at the back of the auditorium with free black women, who had only recently been admitted to the theatre, sitting in separate boxes from mulatto spectators. Nonetheless, it is remarkable in the context of pre-revolutionary Saint-Domingue, and at a time of increasing anxiety about race relations and when increasing measures were being taken to curb the prominence and influence of the free people of colour – exemplified by the sumptuary laws of 1779 that forbade them to wear the clothing and accessories traditionally associated with the white population – that Gluck's work should have reached all these groups simultaneously and in the same building.

It is perhaps remarkable that Gluck's Paris operas reached the French Caribbean at all, for the particular practical difficulties posed by producing large-scale opera in the colonies were noted in the press on several occasions. In the Affiches Américaines of 3 February 1787, for instance, we read that ‘exécuter un grand Opéra sur un Théâtre de Colonie, est une entreprise qui paraît d'abord téméraire’ (58) (producing a large-scale opera in a theatre in the colonies is an undertaking that at first glance seems foolhardy).Footnote 20 The absence of a regular opera chorus in the theatre companies of Saint-Domingue posed a particular problem, and no doubt goes some way towards explaining the complete absence, with the notable exception of Gluck, of productions of serious French opera on the island.Footnote 21 Serious drama was not unknown in Saint-Domingue, and Voltaire's spoken tragedies were undeniably popular, but performances of serious opera were rare indeed. I have found no evidence of any of Lully's tragédies en musique having been performed in Saint-Domingue, nor those of Rameau. Of course Gluck had the advantage of novelty and contemporaneity – something that we know the Saint-Dominguans, whose audience pool and turnover were much more limited than in the metropole, craved.Footnote 22 Whatever the reasons, the absence of Lully and Rameau left Gluck as sole representative on the island of serious French opera in that tradition. Without doubt, then, Gluck occupies a significant position in the history of opera in France's Caribbean colonies.

It is unclear whether the opéra comique Le Cadi dupé, performed many times in Saint-Domingue, was given with Gluck's music or that of Monsigny. Given the popularity on the island of other works with music by Monsigny, the latter seems more likely. Another opéra comique, Le Diable à quatre, was also performed in Saint-Domingue on a number of occasions, and on one of these, in Le Cap, Gluck is explicitly named as the composer of some of the music performed. In the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines for 31 December 1774 we read of an upcoming performance featuring Le Diable à quatre with additional ariettas by M. Gluck (622). While this does not necessarily mean that all the other performances used Gluck's music,Footnote 23 it would appear to be the first recorded mention of Gluck's music reaching audiences in Saint-Domingue. It is possible that an excerpt from a Gluck opera also reached the ears of the Saint-Dominguan audience in Cap-Français on Saturday 18 November 1777. The Supplément aux Affiches Américaines announced that, between Acts 3 and 4 of Grétry's comic opera Zémire et Azor, the orchestra would play the overture to Iphigénie (15 November 1777, 549). This may well have been the overture to Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide, which, as will be seen below, would be performed in Saint-Domingue as a stand-alone piece on several occasions in the 1780s.

Orphée et Eurydice

The information regarding the first documented performance in Saint-Domingue of Gluck's overture to Orphée et Eurydice, however, is much clearer. The Supplément aux Affiches Américaines announced an upcoming concert in Port-au-Prince on 3 June 1779 that would begin with the overture to Orphée et Eurydice, a ‘grand opéra’ by M. Gluck (1 June 1779, 182).Footnote 24 The opera was not performed in its entirety until March 1782. In the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines for 2 March that year it was announced that the local troupe would give the first performance of Orphée et Eurydice, a ‘grand opéra’ in three acts by M. Chevalier Gluck (2 March 1782, 81–82); further details were promised to follow in due course. The level of detail provided a week later is remarkable and merits citation at length:

Le premier acte sera orné d'une décoration nouvelle, représentant le tombeau d'Euridice au milieu d'une allée de cyprès & de lauriers, sur lequel s'appuie l'Hymen avec son flambeau éteint, que des Bergers & Bergères couvrent de fleurs, pendant qu'Orphée est tristement appuyé sur un arbre, où il a pendu son casque & sa lyre. Le second acte sera aussi orné d'une décoration nouvelle, représentant des rochers arides & escarpés, & l'entrée des Enfers gardée par Cerbère; à laquelle succédera une autre décoration, représentant les Enfers, où Orphée se précipite, après avoir touché les larves & les spectres qui lui en empêchaient l'entrée, & qui s'y précipitent avec lui. Un morceau de Musique, analogue à la descente d'Orphée aux Enfers, amène à un autre changement à vue, qui représente les Champs Elisées: on y voit, à travers un fond de gase [sic], des berceaux couverts de fleurs, des bosquets, des fontaines & des tapis de verdure, sur lesquels se reposent les ombres heureuses, qui terminent le second acte par un chœur. L'acte troisième représente une caverne obscure & inhabitée, qui forme un labyrinthe tortueux & qui conduit aux Enfers par des sentiers entrecoupés: on y voit des masses de rochers entassés & couverts de ronces & de plantes sauvages. Orphée tenant Euridice par la main & sans la regarder, paraît dans l’éloignement, & à l'instant où il veut se poignarder, il en est empêché par l'Amour. Le Théâtre change à vue, & représente un Temple dédié à ce Dieu. (9 March 1782, 91)

The first act will feature a new set depicting Eurydice's tomb in the middle of an avenue of cypress and bay trees, with Hymen, his torch extinguished, leaning against it, and which shepherds and shepherdesses cover with flowers, while Orpheus leans sadly against a tree on which he has hung his helmet and his lyre. The second act will also be enhanced by a new set, depicting steep, arid rocks and the entrance to the underworld, guarded by Cerberus. This will be followed by another set depicting the underworld, into which Orpheus throws himself, having touched the tortured ghosts and spectres who tried to prevent him from entering and who follow him in. A piece of music appropriate for Orpheus's descent into hell leads to another transformation, which depicts the Elysian fields. There the audience can see, through a gauze backdrop, arbours covered in flowers, groves, fountains and carpets of green on which the blessed spirits take their rest and who end the second act with a chorus. The third act features a dark, uninhabited cave in the form of a tortuous labyrinth that leads to the underworld by a series of intersecting paths. In the labyrinth there are piles of rocks covered in brambles and wild plants. Orpheus, holding Eurydice by the hand and without looking at her, appears in the distance, and at the moment when he wants to stab himself, he is prevented from doing so by Cupid. The set changes and shows a temple dedicated to Cupid.

The fact that a significant portion of the wording is lifted directly from the stage directions provided in the libretto would suggest that the team were aiming to provide as faithful and complete a performance of the work as possible.

Readers also learned that the role of Eurydice would be performed by Mlle Noël and that of Cupid by ‘la jeune Personne’ (the young person) (91). Mlle Noël was a distinguished French performer based in Port-au-Prince whose repertoire included tragedy as well as comedy and opéra comique. But it is the ‘young person’ who is of particular interest, owing to her exceptional status as a singer-actor of colour. Born in Port-au-Prince, the ‘young person’, later identified in the press as ‘Minette’, had a mixed-race African-European mother and a European father.Footnote 25 A libre de couleur (free person of colour), Minette was the first of a very small number of non-white actors to appear on the public stage in Saint-Domingue.Footnote 26 The fact that she had initially been referred to rather coyly in the press as ‘une jeune personne’ (and then, as she achieved greater prominence, ‘la jeune Personne’) speaks of a degree of discomfort among journalists, who were unsure how to respond to this novelty. Yet her continued presence on stage testifies to her success. The singer-actor was at last called ‘Dlle [i.e. Demoiselle] Minette’ in an article on 4 December 1784, a title usually reserved for white people. This suggests that, in the context of the theatre at least, Minette's African ancestry had become subordinate to her talent as a singer-actor.Footnote 27

Moreau de Saint-Méry commented on Minette's first public appearance in the following terms:

Le 13 Février 1781, M. Saint-Martin, alors directeur, consentit à voir mettre le préjugé aux prises avec le plaisir, en laissant débuter sur ce théâtre, pour la première fois, une jeune personne de 14 ans, créole du Port-au-Prince, dans le rôle d’Isabelle, de l'opéra d'Isabelle et Gertrude. Ses talens et son zèle, auxquels on accorde encore chaque jour de justes applaudissemens, la soutinrent dès son entrée dans la carrière, contre des préventions coloniales, dont tout être sensible et juste est charmé qu'elle ait triomphé.Footnote 28

On 13 February 1781 M. Saint-Martin, then director [of the theatre in Port-au-Prince], agreed to put prejudice head to head with pleasure by letting, for the first time, a young person, a fourteen-year-old creole from Port-au-Prince, debut in the role of Isabelle in the opera Isabelle and Gertrude. Her talent and her enthusiasm, which are rightly applauded on a daily basis, sustained her beginnings in this career, despite the prevailing colonial prejudices, which anyone who is sensitive and fair is delighted to have seen her overcome.

Minette appears to have had certain preferences within the operatic repertoire. She was reluctant to perform local or parochial works, preferring instead to establish a reputation as a ‘French’ actor.Footnote 29 It is possible that Minette aspired to travel to France one day and perform there. Although this would have been exceptional, the success in Paris of a Caribbean musician of mixed racial origins was not unthinkable in the wake of the virtuoso violinist and composer Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745–1799). Born in Guadeloupe to a French planter and a Senegalese slave, Saint-Georges was a musician (and fencer) of considerable distinction, whose compositions were performed in concerts in Paris (where he spent most of his career), Saint-Domingue (a place that he would only visit in the mid-1790s) and elsewhere. Minette may also have heard that Saint-Georges had been passed over as music director of the Paris Opéra in 1776 owing partly to the racial prejudices of some of the singers.Footnote 30 Whatever the exact nature of Minette's aspirations and anxieties, she achieved a degree of agency in the advance publicity for her benefit performance featuring Framery's L'Infante de Zamora, in which she made the following observation:

Ce n'est pas un[e] de ses productions éphémères qui abâtardissent, dégradent pour ainsi dire depuis quelque temps la scène lyrique, qui ne sont que locales, & qui très-souvent ne tiennent qu'aux événemens journaliers de la société privée; c'est un Opéra approuvé du bon goût, & les Amateurs du beau le reverront toujours avec plaisir.Footnote 31

It is not one of these ephemeral productions that have for a while been bastardizing and even degrading the lyric stage, and which are merely local and are very frequently concerned only with the daily events that take place in private society. It's an opera that has met with the approval of those with good taste, and people who appreciate what is beautiful will always take pleasure in seeing it again.

Although she did not take the soprano lead in Orphée et Eurydice (she was only fifteen years old in 1782 and therefore more suited to the role of Cupid), it is significant that Minette should have performed in a genuinely serious work such as Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice at all. More significant still, for our purposes, is the fact that this is surely the first recorded instance of a singer of colour performing in a Gluck opera.

In marked contrast to the Mercure de France’s review of the first performance in Paris, which barely mentions the sets but focuses on the music,Footnote 32 the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines, in an unusually detailed account of the upcoming performance, gives priority to the décor. Each set (décoration) is described individually, including one depicting the entrance to the underworld guarded by Cerberus, and hell itself, complete with tortured ghosts (larves) and spectres, as well as a fiendish labyrinth. The promise of Sieur Fligre, the orchestra's director, playing the harp (evoking Orpheus's lyre) is the final inducement to attend. As it turned out, the premiere of Orphée et Eurydice was postponed until Tuesday 19 March owing to the ill-health of the (unnamed) singer who was to play the male lead (see SAA 16 March 1782, 101).

The fact that the special Christmas Day concert that year in Port-au-Prince (which featured, among others, ‘la jeune Personne’) included ‘le grand chœur d’Orphée & Euridice dans lequel le Sieur Fligue accompagnera de la harpe tous les Solo’Footnote 33 (the big chorus from Orpheus and Eurydice for which Sieur Fligue will accompany all the solos on his harp) would suggest that the performance of the opera had met with some success. This is confirmed by the fact that it was performed again (with all its spectacle) in Port-au-Prince the following year, on Sunday 3 August (SAA 26 July 1783, 420). We know of two further performances of Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice in Port-au-Prince during the colonial period. The first was a benefit performance of the work (organized by Sieur Saint-Léger) with a new set for the hell scenes (AA 4 January 1787, 1). As before, then, one of the principal attractions of the work lay in its elaborate underworld décor. The names of three singers are given for the three principal roles: ‘Demoiselles Sainte-Foix, Minette et le Sieur Saint-Léger’, which we may assume correspond to Eurydice, Cupid and Orpheus respectively. Minette's appearance in the role of Cupid provides an important element of continuity between the earlier performances and this revival (both Mlle Sainte-Foix and Saint-Léger having moved from the theatre in Le Cap to Port-au-Prince the previous year). We do not know if Saint-Léger was capable of singing his role at the original French pitch, written for Joseph Le Gros, who was famous for his ability to sing above the range even of the high tenor or haute-contre, but given that the original version is beyond the range of most high tenors, some judicious rewriting within the designated keys may have offered a more viable option than transposition.Footnote 34

The final performance of Orphée et Eurydice in Port-au-Prince in our period was organized by the actress Mme La Fage, who had only recently joined the troupe. It is somewhat misleadingly billed as a premiere. The Gazette de Saint-Domingue Footnote 35 announced that on 14 February 1791 Orphée et Eurydice, by the famous composer Gluck, would be performed featuring Sieur Ringard, formerly of the Académie Royale de Musique, as Orpheus. This time there is no mention of any décor, but we are told that Sieur Tessier will perform ‘les différens combats des démons avec les costumes analogues aux différentes situations’ (the various demons’ fights, each with costumes appropriate to the situation). Since there are no demons in the Paris version of the opera, this may be a reference to the Furies who block Orpheus's way.Footnote 36

Meanwhile, Orphée et Eurydice was to have received its first performance in the town of Cap-Français on 6 November 1784 (see SAA 27 October 1784, 690), though this was postponed by a week for the simple reason that ‘les décorations, les machines, les ballets, & tous les préparatifs qu'il faut pour monter ce grand Opéra’ (all the sets, machinery, ballets and other provisions that are needed to put on this large-scale opera)Footnote 37 were not ready. Clearly, this was a big undertaking. Mme Marsan, who was widely recognized as the leading actress on the island, and indeed in the French Antilles more generally,Footnote 38 played the role of Eurydice, while Mme Clairville (whose name seems to have been particularly prone to orthographic variants) played Cupid.Footnote 39 The role of Orpheus was taken by M. Larue. In the press, new sets are announced for both hell and the Elysian fields, and the machinist, Bert[h]elet, is mentioned by name. Emphasis is also given to the Dance of the Furies, to be performed by an unnamed amateur and some male acrobats (sauteurs), who appear to have replaced the customary danseurs grotesques. We are told that the chorus would feature the whole company plus some amateur singers. Additional singers were crucial given that, as we have seen, there was no established opera chorus in Saint-Domingue and bearing in mind that the original chorus, according to the libretto, had comprised twenty women and twenty-seven men.Footnote 40 If it was impossible to match the scale of the Parisian performances, the overall impression created is still of an unusually large-scale and lively production.Footnote 41 Interestingly, the event was a benefit performance, organized not by a singer, dancer or designer, but by a member of the orchestra called Sieur Bocquet.

Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice was certainly performed again in Le Cap, although it is difficult to determine the exact number of performances. On 15 February 1786 the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines announced an upcoming performance five days later, featuring Mme Marsan and M. Julien (pensionnaire du roi) in the title roles and organized by the actor Durville. The work in question is Orphée et Eurydice, ‘grand Opéra en trois Actes, Musique de M. Grétry’ (80). Since Grétry did not write such an opera, it is reasonable to suppose that the name Grétry was substituted for Gluck by mistake. Similarly, the announcement on 22 February 1786 of a performance of Orphée et Eurydice the following day, once again featuring M. Julien as Orpheus, would appear to refer to Gluck's opera, although no composer is named, and it is also possible (though not stated) that this was in fact a performance delayed from the previous week rather than a repeat.Footnote 42 On 17 February 1787Footnote 43 the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines included a detailed announcement of an upcoming performance of Orphée et Eurydice:

Les Comédiens du Cap donneront, samedi 31 du courant,Footnote 44 au bénéfice du Sr Quesnet, une représentation d'ORPHÉE ET EURIDICE, grand opéra, dans lequel le rôle d’Euridice sera rempli par Madame Marsan; celui de l'Amour, par Madame Clairville; & celui d’Orphée, par le sieur Delarue. Cette pièce sera ornée de ses ballets des Furies & des Ombres; dans celui des Furies, qui aura lieu à l'acte des Enfers, le Sieur Neveu, amateur, qui a dansé plusieurs fois avec agrément sur ce Théâtre, remplira les principales Entrées sous le costume de l'Envie; le sieur Quesnet, de son côté, dansera à la tête de douze Figurants qu[e] composeront les b[a]llets; dans celui des Ombres, qui aura lieu à l'acte des Champs elisés, Madame Dutilleul & le sieur Quesnet feront une action de pantomime qui se terminera par plusieurs Pas de deux, & Pas seuls. Son jeune Elève y dansera aussi des Entrées.Footnote 45

The actors of Le Cap will perform on Saturday the thirty-first of this month, for the benefit of M. Quesnet, the large-scale opera Orphée et Eurydice, in which the role of Eurydice will be played by Mme Marsan, that of Cupid by Mme Clairville and that of Orpheus by M. Delarue. The performance will include the Dance of the Furies and the Dance of the Blessed Spirits; in the Furies’ dance, which will take place in the act featuring hell, M. Neveu, an amateur who has danced successfully several times on our stage, will perform in the main entries dressed as [an allegory of] Envy. M. Quesnet, for his part, will lead a group of twelve dancers who will perform the ballets. In the Spirits’ dance, which will feature in the act with the Elysian fields, Mme Dutilleul and M. Quesnet will perform a pantomime which will end with several pas de deux and solos. His young student will also dance in the entries.

We note in particular that the dancing master Quesnet has assembled an impressive twelve dancers for the event.

Our final reference to Orphée in Le Cap is refreshingly unambiguous: on 10 January 1789 the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines announced that on Saturday 17 January the company would perform ‘Orphée et Euridice, grand opéra en trois actes, musique du célèbre Gluck’ in a double bill featuring the premiere of an opéra-bouffon, Jérome porteur de chaises, by Jacques Marie Boutet, with music by Sacchini and Galuppi (723). The performance was arranged by the actor Donis, who was clearly something of a Gluck admirer as he had previously organized a benefit performance of Iphigénie en Aulide (see below). Some details are provided in relation to the Gluck production and, as we might expect, the emphasis is on décor and also dance. We are told that there will be three set changes and that a certain Cicery has prepared a new set for the hell scenes in Act 2. The third act will end with a short ballet performed by four young students of the dancing instructor Quesnet (who, we remember, had performed in and put together the 1787 production of the work).

We know very little about the production of Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice in Martinique in summer 1787, but we do have a rare eyewitness account of the performance written by a Danish visitor to the island, Paul Erdman Isert. The new theatre in Saint-Pierre was inaugurated in December 1786 and had a capacity of around eight hundred spectators. The fourth tier of boxes (the ‘paradis’) was reserved for people of colour. More precisely, Isert noted that ‘là sont relégués tous ceux qui ne peuvent pas prouver leur descendance de Parens Européens. On voit souvent ici des Christises, dont la peau est incomparablement plus blanche que celle de nos habitans du Nord de l'Europe’ (all those who cannot prove their European ancestry are relegated to this section. Christises, whose skin is infinitely whiter than that of the inhabitants of Northern Europe, are frequently seen sitting there).Footnote 46 While Isert is no doubt exaggerating the paleness of the skin of certain audience members sitting in the paradis, he offers an important reminder of the fact that racial ancestry and skin colour (and the correspondence between the two) were very slippery categories indeed. Having underlined the local predilection for opera and works filled with singing (as opposed to spoken drama), Isert wrote of his trip to the theatre in Saint-Pierre:

J'assistai à Orphée & Euridice, qui fut assez bien rendu. Mais le Public me parut beaucoup plus content que je ne l’étois moi-même, car avant que la pièce fut finie, on jetta à Orphée une couronne de myrthe, des loges sur le théâtre, à quoi le Parterre applaudit extraordinairement.Footnote 47

I went to see Orphée et Eurydice, which was quite well done. But the audience seemed much more pleased with it than I was myself, since before the work had even finished, somebody in the gallery threw a myrtle crown down to Orpheus on the stage, which provoked rapturous applause from the auditorium.

Although Isert did not quite share the keen enthusiasm of the local audience, this seemingly lukewarm praise should not be dismissed from a writer who was far more interested in flora and fauna than in opera.

Iphigénie en Aulide

A concert took place in Port-au-Prince on 11 April 1784 featuring ‘une ouverture nouvelle, de Gluck; une scene nouvelle à l'Italienne, de Gluck, chantée par le Sieur Durand’ (a new overture by Gluck; a new Italianate scene by Gluck, sung by M. Durand).Footnote 48 These may well have been excerpts from Iphigénie en Aulide. An explicit reference to the opera is first made on 15 January 1785, when the Affiches Américaines announced that the entertainment on 18 January in Port-au-Prince would feature, between the premiere of La Cacophonie (a one-act prose comedy) and a performance of Favart's La Fée Urgelle, a duet from the ‘grand opéra’ Iphigénie, performed by Sieur Durand and the Demoiselle Minette (AA 15 January 1785, 23); the evening would close with an air from Iphigénie, sung by Sieur Durand and an anglaise danced by Sieur Acquaire.Footnote 49 Later in the same year, the Affiches Américaines announced that Gluck's overture to Iphigénie en Aulide would feature between the second and third acts of Beaumarchais's Le Mariage de Figaro (AA 22 October 1785, 467). The duet from Iphigénie was clearly popular as a concert piece, since it featured at the end of a big musico-theatrical event in Port-au-Prince that also included the overture to the same opera, on 4 August 1788 (AA 31 July 1788, 376), sung by Mme Caillé and the Sieur Saint-Léger. The duet was performed again by request in a concert in the same town on 31 January 1789, sung by Mme Caillé and an amateur. It also featured on a concert programme in Le Cap, sung by Mlle Buron and an amateur, on 6 July 1789.

Meanwhile, news of Gluck's death in November 1787 reached readers of the Affiches Américaines on 23 February 1788. The notice included the following report, which is a rare reference in the local press to the fight between the Gluckists and the Piccinnists, and which no doubt served the future performances of Iphigénie en Aulide well:

La perte de ce célèbre Musicien cause des regrets à toute l'Europe. J. J. Rousseau a soutenu que nous n'aurions jamais de musique dramatique sous des paroles françoises: il se retracta après avoir entendu Iphigénie en Aulide.Footnote 50

The loss of this famous musician is a source of regret to the whole of Europe. J. J. Rousseau claimed that dramatic music was impossible with French words: he retracted this after hearing Iphigénie en Aulide.

The premiere of the complete opera in Port-au-Prince did not take place until 5 September 1789. The announcement in the Affiches Américaines on 29 August explicitly indicates that the idea of putting on the whole opera followed on from the success of the two excerpts sung at the Caillé concert the previous year. More significant is the suggestion that it is particularly challenging to put on such a work in Saint-Domingue. We read that the musician Sieur Simon (the beneficiary and organizer of the soirée) ‘n'a rien négligé pour que l'exécution réponde au désir qu'il a que cet Opéra soit rendu aussi bien que les circonstances locales le permettent’ (has made every effort to fulfil his wish that the performance of this opera be as good as local circumstances permit). While this formulation, which betrays an element of false modesty, is not unheard of in such announcements, it is also clear that Gluck's ‘grands opéras’ posed particular challenges to theatre companies more accustomed to performing and producing lighter works with no chorus. The point is underlined further in the same article as we read that ‘les répétitions multipliées qu'il en a fait faire depuis deux mois, lui donnent lieu d'espérer que son attente ne sera pas vaine’ (the additional rehearsals that he has organized over the last two months give him good reason to hope that his expectations will be met).Footnote 51 The second performance of the work over a year later, also organized by Sieur Simon, likewise required extra rehearsals (see AA 4 December 1790, 620, and AA 9 December 1790, 623–624) and, as will be seen, performances of the same work were also delayed in Cap-Français. The Port-au-Prince performance, originally scheduled for 11 December 1790, appears to have been postponed by a week, for in the Affiches Américaines of 11 December 1790 a performance is announced with otherwise identical wording for 18 December (632).Footnote 52

It is particularly interesting to speculate how the character of the female slave and in particular the ‘air pour les esclaves’ in Act 2 were received in this slave colony. There is ample evidence that the white population of the colonial Caribbean was both fearful of and fascinated by the dances that slaves regularly performed as a form of recreation and, as the colonials rightly suspected, also as a form of resistance.Footnote 53 Slave dance was, then, a recognized phenomenon among the theatre audience in Saint-Domingue. However, it is not certain that the audience would have made any connection between on the one hand Gluck's rendering of slave music, which, despite being composed in the exotic style,Footnote 54 is distinctly European, and on the other the music used to accompany the slaves’ dances that many of them will have heard on their plantations. The same argument may apply to the dance movements, although these would have been easier to change. It is possible that Gluck's slaves offered the Caribbean audience a rare opportunity to savour their superiority in matters of slave culture over the metropolitan audience that they otherwise sought to emulate; it is also possible that Gluck's slaves offered a fleeting reminder of the unwelcome reality of slave gatherings and the potential threats that these posed. It is possible too – and perhaps more likely – that these operatic slaves passed by unnoticed even as the debates about the future of France and its colonies raged on in the background.Footnote 55 In the absence of any written testimony, we cannot know for certain.

Turning now to Le Cap, as had been the case in Port-au-Prince, Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide first reached the audience in the form of excerpts. On 31 May 1786, the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines announced a ‘Grand concert’ on Saturday 3 June, organized by Mme Caillé, who, we remember, would perform the same duet in another big concert in Port-au-Prince in August 1788.Footnote 56 The concert began with the overture to Iphigénie en Aulide and featured, among other pieces, ‘une ariette d'Iphigenie en Aulide, grand Opéra, chantée par un Amateur’, and ended with ‘le Duo d'Iphigenie en Aulide, chanté par Madame Caillé & un Amateur’ (281). Presumably the arietta and the duet were the same as had been performed in Port-au-Prince in January 1785. The first performance in Le Cap of the whole opera would not take place for another eighteen months (a somewhat longer interval between the concert featuring excerpts and the full work than in Port-au-Prince). The Le Cap premiere of Iphigénie en Aulide, organized by the actor Donis, was originally scheduled for 29 December 1787 (see SAA 22 December 1787), but this was in fact postponed until 12 January 1788. The announcement on 22 December 1787 praises the work and its composer in the highest terms: ‘cette pièce est au dessus de la première classe des chef-d’œuvres: comme son Auteur est distingué dans le nombre des célèbres Musiciens, tout éloge est au dessous de sa réputation’ (983) (this work is better than the greatest masterpieces; as its author is distinguished even by the standards of the most famous composers, any praise is beneath his reputation). This is followed by an interesting account of the extraordinary power of Gluck's music, which is described as being in competition with its visual power: ‘la musique qui remue les cœurs à son gré, qui peint et inspire toutes les passions, ne peut laisser des regrets qu’à l’œil avide des Spectateurs’ (the music, which moves people's hearts at will, which paints and inspires all the passions, can leave only the keen eyes of the spectators wanting). The suggestion is that while local spectators are as a rule moved principally by the visual effects of opera, the particular qualities of Gluck's music are equally moving. If opera, and particularly opéra comique, has become mere spectacle, this one (a ‘grand opéra’) reasserts the primacy of music.

The visual appeal of the opera is not, however, overlooked. We read that

le Sieur Donis a suppléé à ce vide par la décoration nouvelle qui représente le Camp des Grecs, les costumes, la quantité d'assistants, & toute la pompe que peut permettre le local; il ose se flatter qu’à l'exception des ballets, le Théâtre de cette Ville pourra, ce jour-là, soutenir la rivalité avec les premières Villes de France. (983)

Mr Donis has filled this gap with a new set that represents the Greek camp, with the costumes and the number of assistants and all the pomp that the setting allows; he dares to flatter himself that, with the exception of the ballets, the theatre of this town will, on that day, be able to rival the great cities of France.

The comparison with performances in France was both an aspiration of French Caribbean theatre and a means of attracting an audience. Given that ‘grand opéra’ was not the preferred genre of the Saint-Dominguan audience, it was perhaps particularly important to stress the similarity with performances in the metropole in this instance. As it happens, the review of the Parisian premiere of Iphigénie en Aulide in Le Mercure de France had praised the work highly but complained precisely about the failure to portray adequately the customs, costume and games of the Greeks in the musical interludes.Footnote 57 Indeed, it would seem that Gluck's original vision of how these should have been portrayed was replaced at the Parisian premiere with ‘unrelated subjects’.Footnote 58 With regard to the dances in Cap-Français, it is not absolutely clear whether or not these are simply to be omitted (undanced) or performed on a significantly smaller scale than in France.

On 5 January 1788 the Supplément aux Affiches Américaines made the following, rather less upbeat, announcement: ‘Les marches, les chœurs et la quantité de répétitions nécessaires pour l'opéra d'IPHIGENIE EN AULIDE, en ont retardé la première représentation’ (693) (the marches, choruses and number of rehearsals required for the opera Iphigénie en Aulide have put back the first performance). The performance, readers are told, will now take place on Saturday 12 January, barring any insurmountable obstacles.

Iphigénie en Tauride

There is only a single documented performance in Saint-Domingue of Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride, ‘grand Opéra en 4 Actes, musique du celèbre Gluck, orné de tout son spectacle’, organized by Sieur Romanville in Le Cap on 8 October 1785 (see SAA 28 September 1785, 430). Although I have found no evidence of excerpts from the work being performed in concerts prior to the operatic premiere, the advance publicity suggests that the work is well known to the Saint-Dominguan public: ‘on se croit dispensé de faire la description de la Piece, vu que les Amateurs la reconnoissent comme un de ses Chef-d’œuvres’ (430) (we believe that we may refrain from describing the work, as it is well known to devotees as one of his masterpieces). It is conceivable that one or two members of the audience in Le Cap might have seen the opera in France, but the publicist seems to be relying above all on Gluck's reputation as a composer having reached Saint-Domingue by other means. Attentive readers of the Affiches Américaines might have recalled reading about the performance in summer 1781 of Iphigénie en Tauride at the Trianon in honour of Emperor Joseph II (25 December 1781, 501). A more reliable collective memory was probably the success of the performance, featuring Mme Marsan, of Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice in Le Cap the previous year. There is mention of ‘les soins que les Acteurs & Actrices ont porté pour la réussite de son éxécution’ (the care that the actors and actresses have taken to ensure a successful performance), and readers are told that Mme Marsan would perform the role of Iphigénie (430), but no appeal is made, for instance, to the visual attractions of the upcoming performance or to any new or special décor.

Although there is no evidence that Iphigénie en Tauride was ever performed in Port-au-Prince during the colonial period, we do read in the Affiches Américaines of several performances of Les Rêveries renouvellées des Grecs, an opéra-bouffon, subtitled La Parodie d'Iphigénie. This is the operatic parody with a text by Charles-Simon Favart and music, mainly in vaudevilles, by F. J. Prot, and first performed at the Comédie Italienne in Paris on 26 June 1779, just over a month after the premiere of the opera on which it was (partly) based. The work is described in the Mercure de France as a ‘parodie des deux Iphigénies en Tauride [those by Gluck and Claude Guimond De La Touche], en trois Actes & en vers, mêlés de Vaudevilles’ (a parody of both Iphigénies en Tauride in three acts and in verse, interspersed with vaudevilles), and its similarity to Favart's Petite Iphigénie (1757) is underlined.Footnote 59 The island premiere of the work featured on a double bill with a comedy called La triste journée. It is described in the Affiches Américaines simply as a ‘parodie d’Iphigénie en Tauride, Opéra en 2 [sic] actes, Musique de M. Prot’ (a parody of Iphigénie en Tauride, an opera in two [sic] acts, with music by M. Prot).Footnote 60 We learn too that between the two works M. Texier and Mme Tessière would perform a pas de deux related to the opera, just as it was performed in Paris. Further documented performances of Les Rêveries renouvellées in Port-au-Prince took place in February and March 1786, January and March 1787 and March 1788. We know that the performance(s) in January 1787 featured Mlle Sainte-Foix as Iphigénie and M. Saint-Léger as Pylades (AA 4 January 1787, 1 and AA 11 January 1787, 13). Given that Sainte-Foix and Saint-Léger were members of the troupe at Le Cap when it gave its performance of Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride, coupled with the fact that the Port-au-Prince troupe was also preparing a performance of Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice at this time (featuring Sainte-Foix and Saint-Léger alongside Minette, as we have seen), it is possible that this performance of Les Rêveries renouvellées drew more obviously on Gluck's opera than earlier performances. Meanwhile, the fact that Gluck's ‘grand opéra’ reached Port-au-Prince only in this light-hearted form is another reminder of the local theatrical preference for lighter works.Footnote 61

CONCLUSION

It has been seen that in the context of eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue, Gluck was the undisputed representative of serious French opera. We have examined the three Paris operas that were performed on the island (and in one instance also in Martinique) in turn in an attempt to understand how each of them fared when translated to this new context. It is clear that Orphée et Eurydice was the most popular of the three by a considerable margin, and that the opportunities it offered for interesting stage scenery formed a significant part of the work's appeal. Clearly Orphée, with its extended hell scenes, appealed to the Saint-Dominguan audience's predilection for visual interest. While it is tempting to speculate that the reason Iphigénie en Tauride seems to have received only a single performance on the island might have been the potentially uncomfortable theme of tensions between different nations and the looming threat of a popular revolt, it is more likely that other factors came into play, notably the absence of a love plot – an absence noted in the Journal de Paris’s review of the Paris premiere.Footnote 62 In chronological terms, the Appendix below confirms that at least one performance of a Gluck opera was given every year in Saint-Domingue between 1782 and 1791 – a remarkable statistic by any standard, and particularly in a theatrical context that required constant novelty and boasted fewer resources than were available in France's major cities, which meant that there was no regular opera chorus. Moreover, Gluck's operas attracted the particular attention of a host of individual troupe members – singers, actors, musicians and one dancer – who elected to put on these more demanding works at their own risk. We have seen that Gluck's operas drew on the talents of the leading performers on the island, and that his Cupid was performed by a woman of colour in a time and place where the presence of a non-white actor on stage was still extraordinary. Gluck's music was also performed by slave musicians in the theatre orchestras. It is hoped, then, that this survey of performances of Gluck's operas in the French colonial Caribbean has added an important dimension to our understanding of the extraordinary scope of his internationalism and of the different social groups who were exposed to his work. The research method that has been applied here to Gluck could usefully be applied to other composers and playwrights whose works were performed in Saint-Domingue, including a small number of local playwrights and composers who together created a rich culture that overlapped with – but was also distinct from – that of metropolitan France.

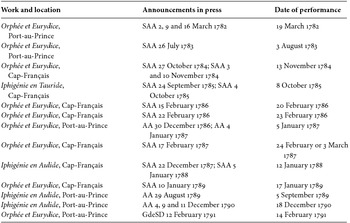

APPENDIX

Complete performances of Gluck's Paris operas in Saint-Domingue