INTRODUCTION

In 2011, Canada had a foreign-born population of approximately 6,775,800. They represented 20.6% of the total population, the highest proportion amongst the G8 countries. With an annual influx of 240,000,Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 this cohort is expected to continue to grow. Lower socioeconomic status (SES),Reference Brar, Tang and Drummond 2 – Reference Dunlop, Coyte and McIsaac 5 immigrant health, and unemployment all reduce primary care use.Reference McDonald and Kennedy 6 Immigrants are defined as an at-risk population due to their unique characteristics that reduce their use of primary care.Reference Sanmartin and Ross 7 – Reference Muggah, Dahrouge and Hogg 9

Data regarding immigrants’ tendency to access emergency health care are conflicting. Several studies have found increased emergency department use among immigrant populations,Reference Hjern, Persson and Roen 10 – Reference Rué, Soler-González and Bosch 14 whereas others have found decreased use.Reference Wen and Williams 15 – Reference Buron, Garcia and Vall 18 Across the general population, a lack of primary care physician seems to increase the likelihood of emergency department use.Reference Mian and Pong 13

The lack of health care use has been correlated with poor health outcomes.Reference Wu, Penning and Schimmele 19 Given the already lower SES among immigrant populations in Canada,Reference Dunn and Dyck 20 – Reference Ng, Wilkins and Gendron 22 it is important to understand the factors that impact both primary and emergency department care use in this group in order to guide the adaptation of our health care system to accommodate these factors and thus ensure equitable health care use.

The objective of this paper was to assess whether immigrants lacking primary care would demonstrate reduced likelihood of using the emergency department as a regular care access point compared to Canadian-born patients similarly lacking primary care. Our secondary objective was to assess whether commonly reported factors reducing use of primary care would impact the emergency department tendencies studied here.

METHODS

Study population

The analyses for this study were based on data from the 2007-2008 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). This is a cross-sectional survey collecting information from those ages 12 years and older living in private dwellings in Canada. Excluded from the study population were individuals who lived on First Nations reserves or crown lands, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, people in institutions, homeless people, and people living in remote regions. The CCHS covers approximately 98% of the Canadian population ages 12 and over.

A multistage, stratified sampling design was used, with each dwelling as the final sampling unit. Demographic data were obtained for 144,836 households, and one or two people per household were asked to complete an in-depth interview. From this sample, 134,073 individual responses were obtained, giving a national response rate of 93%. The survey included questions related to health status, health care use, and health determinants.

From the survey database, we identified people who reported having no primary care physician (n=15,554). We did not use any age or province restrictions. In the health care utilization module, respondents were asked whether they had a primary care physician; if they said no, they were asked whether they had a regular place that they attended for care. If they answered yes, they were asked where this place was, and those responding to this question defined our study population.

Exposure and outcome variables

Our outcome variable was defined as use of the emergency department as the primary access point for health care. We dichotomized the possible answers to the CCHS question, “Where is your usual place for health care?” into emergency department versus other. Exposure variables were education, self-reported health status, and employment. Covariates were previously reported factors that altered emergency department use: age, region, income, chronic disease, gender, self-reported mental heath status, and difficulty attending medical appointments (defined as a mobility issue). Education was dichotomized into those with an education above or below the secondary school level. Income was dichotomized into above or below $20,000. Health status and mental health status were both self-reported on a scale of 1 to 5; these were collapsed into poor (< 3) or good health.Reference Reitmanova and Gustafson 3 – Reference Dunlop, Coyte and McIsaac 5 Employment status was dichotomized into employed and unemployed. Age was collapsed into four categories: <18; 18-45; 46-65; and > 65. Immigrant status was self-reported as yes or no. Chronic disease was a composite variable, and yes was defined as any respondent reporting a history of asthma, arthritis, mood or anxiety disorder, diabetes, heart disease, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic bronchitis. For the mobility issue covariate, yes was defined as difficulty attending a medical appointment.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each variable were calculated. Weighted logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate the importance of individual risk factors and their interactions after adjustment for relevant covariates. Model parameters were estimated by the method of maximum likelihood, and the Wald statistic was used to test the significance of individual variables or interaction terms in relation to emergency department choice. To model the effect of covariates and independent variable (immigrant status) on the emergency department as a regular place to seek care, we constructed a model with regular place of care as the dependent variable. To describe the variation in impact of covariates on describing the emergency department as a regular point of access for care, we split our sample into immigrant and non-immigrant populations and then analysed our model with covariates now as independent variables and immigrant status not included.

The CCHS 2007-2008 data were based on a complex survey design incorporating stratification, multiple stages of selection, and unequal probabilities of selection for respondents. Therefore, standard statistical methods may not be appropriate for the analysis of these data. The CCHS microdata documentation provides guidelines stating that population sample weights (expansion weights) must be used to produce correct population estimates. This weighting takes into account the patterns of missing data and the oversampling of some strata. The CCHS 2007-2008 public release data file provides these population weights. In our models, records that contained missing data for any of the explanatory covariates were deleted if they compromised greater than 10% of the available data.

RESULTS

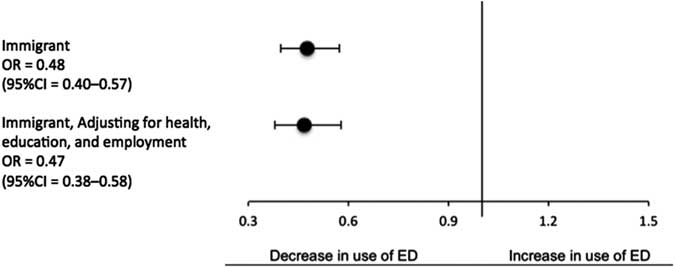

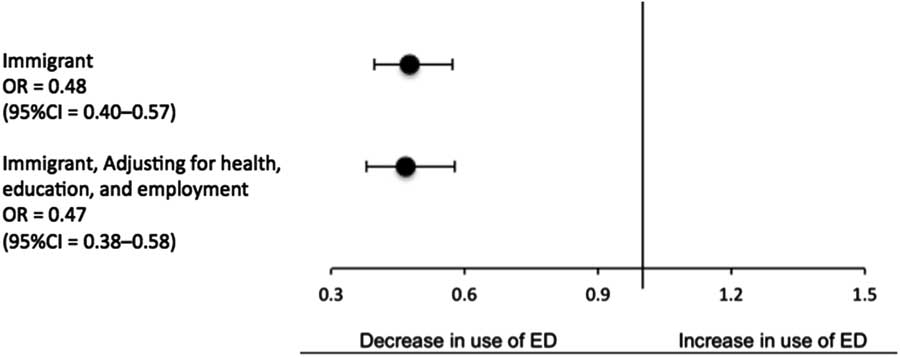

The study population included 15,554 survey respondents (immigrants n=1,767) from across Canada who did not have a primary care physician but did have a regular place to go for health care. The emergency department was the primary access point for 2,750 (18.7%) respondents, a weighted representation of 456,656 Canadian residents. The sample comprised 57.3% males. The response rates across individual provinces varied from 78.5% to 87.0%. In our study, immigrants without a primary care provider were less likely to report that they use the emergency department as a regular point of care access than Canadian-born respondents similarly lacking primary care (odds ratio [OR]=0.48 [95% CI 0.40 – 0.57]). Adjusting for health, education, or employment had no effect on this reduced access (OR=0.47 [95% CI 0.38 – 0.58]) (Tables 1–4; Figure 1). The presence of a chronic condition, greater age, less than secondary school education, and male respondents had an increased use of the emergency department in a non-immigrant population but had no effect in an immigrant population. Income was not used in our model because > 20% of data was missing.

Figure 1 Unadjusted and adjusted odds of using the emergency department for regular health care (adjusting for education, employment, and health status) among an immigrant population versus a non-immigrant population.

Table 1 Characteristics of a study population, respondents without a primary care provider who have a regular place they seek care, compared across immigrant status

Table 2 Comparison of reported factors affecting likelihood of using the emergency department for regular health care between an immigrant and non-immigrant population

* denotes statistical significance.

Table 3 Comparison of the odds of an immigrant population using the emergency department for regular health care, unadjusted versus adjusted (employment, health, and education)

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Our study has several limitations. One important limitation is that all of the data collected were self-reported and thus subject to recall bias – namely, the self-reported tendency for emergency departments as a regular point of health care access because it was our primary outcome. The variable education was collapsed into two categories. This could potentially lead to misclassification bias; however, in analysing the maximum likelihood test, the larger number of categories did not add significantly to the model. The CCHS is from 2008, and thus trends may have since shifted. Finally, unmeasured variables that may have impacted emergency department use (health literacy, cultural preferences, and language) were not reported in the CCHS data and therefore could not be controlled for in the regression analysis.

Strengths of our study include a large sample size giving us power to detect smaller effects. Our sampling error is reduced with our large sampling size with a complex survey and a high response rate. Our results are also generalizable across Canada given that our source data were a national survey.

DISCUSSION

The 1984 Canada Health Act (CHA) sets out the primary objective of health care: “to protect, promote, and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers.”Reference Canada 23

Immigrants without a primary care physician are less likely to report the emergency department as a regular point of health care access, and thus may receive different care than non-immigrants. Previously reported factors leading to reduced use of primary care do not account for the reduced tendency to use the emergency department by an immigrant population seen in this study.

Literature on immigrant use of the emergency department is conflicting. Several studies have found increased emergency department use among immigrant populations,Reference Hjern, Persson and Roen 10 – Reference Rué, Soler-González and Bosch 14 whereas others have found decreased use.Reference Wen and Williams 15 – Reference Buron, Garcia and Vall 18 These studies tended to define immigrants as a homogeneous population and did not take into account patient access to a primary care provider or potentially confounding factors such as SES, the healthy immigrant effect, education, and legal issues surrounding immigration.

Even after controlling for health status, education level, and employment, immigrants were less likely to report using the emergency department as the regular place they sought care. Ahmed et al. (2015) discuss cultural barriers to accessing primary care that exist outside of education and SES.Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 There may also be difficulties understanding a new health care system in a different language.Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 , Reference Fiscella, Doescher and Saver 24 , Reference Ng 25 Additionally, there may be confusion or frustration with the Canadian system with respect to specialist referrals and management of patient information, which differs from the private systems in other countries.Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 , Reference Ng 25 , Reference Liu and Quan 26 Furthermore, differences in cultural norms may become apparent in the context of emergency department care, such as preferred physician gender, sharing hospital rooms, discussing sensitive issues, or views of what health problems warrant seeking medical care.Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 , Reference Ng 25 These factors, considered together, seem to represent features of health literacy, which would be understandably lower in those who are new to the Canadian system. As our results suggest, they may be acting independently of employment, health status, and education and impacting emergency department use among immigrants.

Another potential explanation for the reduced likelihood of emergency department use for regular care is that the immigrant population is healthier, as described by the healthy immigrant effect.Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 However, this effect has been shown to be not only temporary but also reversed over time,Reference Ahmed, Rumana and Barron 1 and because our immigrant population was defined as foreign-born and thus not limited by the duration of time lived in Canada, the health status of recent and less-recent immigrants was likely homogeneous. As a future direction, the effect of health status on health care use would be interesting to study with narrower population definitions.

We have shown that immigrants without a primary care physician are less likely than Canadian-born individuals to regularly seek care in the emergency department. In a universally funded health system where inequalities in care delivery continue to exist, we need to further evaluate whether this reduced use equates to reduced access.

CONCLUSION

The provision of health care to an immigrant population is a complex, diverse, and ever-changing process. Canadian immigrants without a primary care physician are less likely than non-immigrants to use the emergency department as for their regular health care. Factors that impede Canadian immigrants’ use of primary care do not adequately account for this decreased tendency. With an ever increasing number of immigrants becoming new Canadians, we must further elucidate the factors that impact their health care use so as to ensure that our system is as equitable as possible.

Table 4 Comparison of regular places for health care between immigrants and non-immigrants without a primary care physician

Competing interests: None declared.