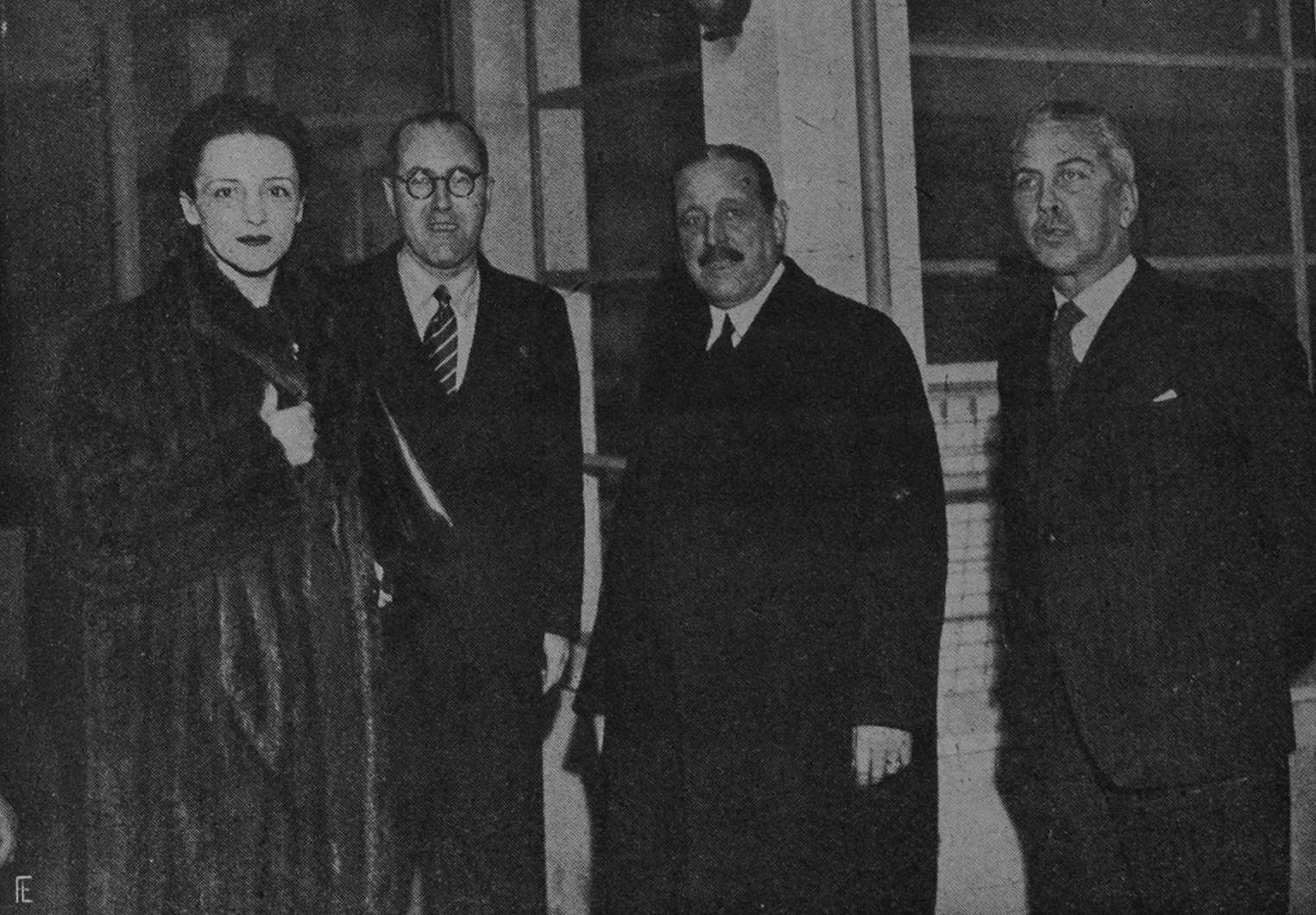

On the second-floor corridor of the Portuguese Oncology Institute (Instituto Português de Oncologia, IPO), multiple objects and photographs are arranged in cabinets to represent the history of the institute since its creation in 1923. Among these, next to a photograph of a ‘roentgentherapheutic’ apparatus, is a picture of a woman and three men. It is the photograph taken on 9 January 1940 showing Francisco Gentil, the IPO's founder and director, and Francisco Bénard Guedes, the IPO's chief radiologist, with Ève Curie, the daughter of Marie and Pierre Curie, and Raymond Warnier, the director of the French Institute in Portugal.Footnote 1 One floor above, the photograph resurfaces in the January 1940 issue of the IPO's bulletin (1934–74) archived at the library. It is the first group portrait ever reproduced in the bulletin.

Figure 1. Ève Curie, Raymond Warnier, Francisco Gentil and Francisco Bénard Guedes at the IPO, from Boletim do Instituto Português de Oncologia (1940) 7(1), p. 1. Photographer: Manuel Barbosa. ©Instituto Português de Oncologia, Lisbon.

As the bulletin recounts, Ève Curie stopped in Lisbon while on her way to the US. On this occasion, she visited the IPO's Radium Pavilion, the first facility created in Europe in order to follow the international guidelines for radioactive containment established at the 1928 International Congress of Radiology held in Stockholm.Footnote 2 There, she was photographed together with two of the IPO's experts, promoting the ‘curie-therapy’ carried out in the institute, as well as illustrating that the IPO's project stemmed from international scientific and political coordination. This started during the scientific progressivism of the First Republic (1910–26), but survived throughout, and was in fact embraced by, the dictatorship of Estado Novo (1933–74) led by António de Oliveira Salazar.Footnote 3 As the minister of finance during the early years of the National Dictatorship Government (1928–33), Salazar arranged the necessary funds to erect a pavilion, in which radium-based cancer treatments could be safely applied.Footnote 4 Mentions of Stockholm and Salazar were often used and promoted by the IPO in the years following the launching of the Radium Pavilion in 1933 – often to secure public funding to further advance cancer research and prevention.

In the photograph at the pavilion, Ève is facing the camera, as if gazing directly at the ‘afterlife’ of the photograph, at its future beholder, welcoming the reader of the IPO's bulletin into the facility. This moment in which the group breaks away from the rest of the crowd in order to gather for the photographer was also captured in film for the newsreel Jornal Português (1938–51). The latter combined a series of episodic ‘actualities’ to be screened at national theatres as complement to feature films; these were commissioned by the Estado Novo's propaganda department – the National Propaganda Secretariat (Secretariado da Propaganda Nacional, SPN) – aiming at educating audiences during commercial screenings. Ève's departure from Lisbon also deserved a mention in the Jornal Português. In promoting the scientific innovation of the regime, through the international expertise of the IPO's project, both media also asserted the non-‘peripheral’ location of Portugal, stressing instead its positioning as a meeting point between the US and Europe, and adding to the country's public image of neutrality during the Second World War.

Figure 2. Ève Curie, Raymond Warnier, Francisco Gentil and Francisco Bénard Guedes posing for the photo op. Frame from Jornal Português, 13 (Chapter: Ève Curie. Visit to Instituto Português de Oncologia), 1940. © Col. Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema, Lisbon.

Figure 3. Ève Curie boarding the liner Vulcania. Frame from Jornal Português, 13 (Chapter: Ève Curie. Visit to Instituto Português de Oncologia), 1940. © Col. Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema, Lisbon.

This public framing of international strategies in order to further develop and strengthen agencies with diplomatic aims is a process traditionally examined in the literature as ‘public diplomacy’.Footnote 5 In an increasingly mediatized society, non-state actors, domestic non-governmental organizations and international institutions, through professional enterprises and personal relationships, public events and offerings, visual and media representations, are also key to the galvanization and administration of international affairs – often considered a form of ‘soft power’ in diplomacy studies.Footnote 6 In what follows, I argue that the visual representations of Ève Curie at the IPO enacted public diplomacy in several ways. They intended to secure international, official and public validation of the IPO's advertising activities. These images also aimed to promote Portuguese modernistic nationalism and ‘neutrality’ during the Second World War, especially through advertising the ties with France and the US that their joint promotion of cancer treatment displayed. That Ève was both photographed and filmed at the Radium Pavilion in 1940 demonstrates the significance of the Curies’ legacy: the images created of her were able to perform visual diplomacy with regard to the promotion of scientific and transnational state relations.

In the first half of the last century, the increasing mediatization of the Curies, and the subsequent mediation of their effect, was integral to the consolidation and management of the transnational fight against cancer uniting the US, France and Portugal. In these three countries, the Curies’ treatment prompted cancer campaigners to persuade public opinion about the merits of radium-based therapy, and in turn these propaganda campaigns informed diplomatic relations between their administrations. The promotion of cancer treatments started to have a diplomatic dimension from in 1921. This was when the two daughters of Marie Curie, Ève and Irène, accompanied their mother to receive a gram of radium at the White House from President Warren Harding. At the time, the American Society for the Control of Cancer (ASCC) tried to damp down the media frenzy which portrayed Marie's enterprise in the US as heralding the ‘end of all cancers’, positioning the Curies’ tour as a wider contribution to scientific expertise and international collaboration.Footnote 7

Unlike her daughters, however, Marie Curie benefits from an extensive and diverse historiographic literature, one that goes far beyond traditional ‘hagiographic’ formats. Particularly, the historians Julie de Jardins and Eva Hemmungs Wirtén have explored the mediatic ‘making’ of Marie Curie that led to her journey to the White House in 1921.Footnote 8 Examining a wide range of sources, they show how Marie Curie came to represent a persona of hardship, devotion and scientific impartiality in a way that did not always correspond to reality. Historian Natalie Pigeard-Micault, working closely with the Musée Curie archives, makes a similar claim.Footnote 9 Scholars addressing the history of radioactivity, such as Maria Rentetzi, Xavier Roqué and Soraya Boudia, observe a different sort of complexity regarding Marie Curie too, in that she was both a scientist and an industrialist. For example, Marie looked forward to the growth of the US radium industries as a means to enhance her own research and laboratories in both France and Warsaw.Footnote 10

As this article shows, Ève carried forward and further galvanized the scientific and international relations that her mother had initiated. Yet, in contrast with the activities of her mother and her sister Irène, Ève's initiatives following Marie's death in 1934 have been overlooked. We know a great deal more about Irène, who continued her mother's research and, in 1935, together with her husband Frédéric Joliot, was rewarded with a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of artificial radioactivity.Footnote 11 Ève was instead responsible for writing the biography of her parents, Madame Curie (1936), which played a role in cancer treatment campaigns internationally. In this way, she played an equally significant but less acknowledged role in international affairs. The 1938 picture of the chargé d'affaires of the French Republic, Jules Henry, demonstrates this, as he was photographed receiving a specially bound edition of Ève's Madame Curie from the Women's Field Army of the ASCC, attesting to the ties uniting the US and France in the fight against cancer. The IPO, furthermore, was a member of the French-based International Union against Cancer, and was very much aligned with the ASCC's model of cancer propaganda.Footnote 12 Both the biography Madame Curie and the (filmed) picture of Ève in Portugal were part of a mediatized public-diplomacy campaign to foster transnational networks in the fight against cancer uniting Portugal, France and the US, whilst simultaneously shaping public perception about the benefits of radium therapy.

This article therefore ties Ève Curie's appeal as a mediatic icon of radioactivity to interwar international relations. It appraises well-known events involving Marie Curie and her daughters through the lens of visual diplomacy of cancer treatments. Particularly, it explores the visual promotion of the Curies’ international campaigns and how they were locally and nationally incorporated, appropriated and represented. The first section of this article examines the events surrounding Marie Curie's 1921 US tour, in the context of the American and French cancer campaigns of the time, with regard to the ways in which these framed both the search for a cure for cancer and the public perceptions of the dangers of radiation exposure. The second section looks at the photograph of Jules Henry in 1938 and the extension of this campaigning to Portugal. Finally, the last section deals with the photograph of Ève at the IPO, also captured on film as a propaganda tool, exploring questions of visibility and invisibility in both media, and in relation to the Estado Novo during the advance of the war.

‘The two greatest republics in the world’

The mass media, particularly newspapers and magazines, but also photography, radio and film, had already widely advertised Marie Curie's radium enterprise in the US by the time her daughter Ève took on the task of furthering this campaigning following her mother's death in 1934. The editor of the New York-based magazine Delineator, Marie Brown Meloney, played a key role in this promotion. Her Radium Fund campaign culminated in the Polish French scientist receiving a gram of radium at the White House from the US president, Warren G. Harding. This represented a public intervention on the part of the ASCC to promote the scientific potential of Curie's work in advancing and perfecting radium-based cancer therapy, an agenda uniting the US and France in the fight against cancer.

After meeting Marie Curie in Paris, during the spring of 1920, Meloney decided to mount a media crusade in Curie's favour. Once back in New York, she wanted the US government to support the radiochemist by supplying more radium to her laboratory in Paris. Confident that her compatriots would support her cause, Meloney founded two committees. One was oriented to laypople with humanitarian aims, such as the ASCC founders, and included women; the other, launched to complement the latter, was composed primarily of medical men and leaders in cancer research.Footnote 13 Together, the two committees launched a nationwide campaign for the Marie Curie Radium Fund. When their target of raising enough money to purchase a gram of radium was met, Marie was asked to accept the gift in person. This was a mutually beneficial act: Curie would be supplied with radium, the fundraisers would be publicly seen to have achieved their aims, and the US administration would also be able to use Curie's image for its own humanitarian and professional aims.Footnote 14

At a time when women had just won national suffrage in the US, radium became ‘a woman's gift to the world’ and a triumph of both ‘faith over hardship and doubting men’ – as advertised in the Delineator.Footnote 15 The Radium Fund campaign prompted public (and often unrealistic) expectations about what it really meant to be a female scientist working with radium. Meloney's main ambition might have been to raise the profile of Curie's enterprise in the US, alerting local industrialists and administrators to her need for more radium. However, through this media campaign, Meloney also turned Curie into a public figure, publicizing the Polish French scientist as a symbol of scientific womanhood and as a heroine of radioactivity in the fight against cancer.

In fact, news that the French government was funding large quantities of radium made several of Meloney's potential donors doubt the value of their generosity.Footnote 16 However, Marie Curie had something else in mind for her US donation. Whereas French radium was reserved for medical use, her American gift would be utilized for pure scientific research which, it was hoped, could eventually lead to a better cure for cancer.Footnote 17 The Delineator's April issue opened with an article entitled ‘That millions shall not die!’, for ‘the greatest woman’ could save a world where ‘millions’ were ‘dying of cancer every year!’Footnote 18 Earlier in March, Carrie Chapman Catt, pacifist and suffrage organizer, had written ‘Helping Madame Curie to help the world’ in the Woman Citizen.Footnote 19 For Catt too, what Marie desired the most was not only radium, but that ‘it should not be used for any ordinary purposes’ and ‘be kept sacredly for experimentation and especially in reference to the cure of cancer’.Footnote 20

Indeed, ballooning support for the Radium Fund suggested to Meloney that one hundred thousand women and a significant number of medical men believed that Curie's cause was their own.Footnote 21 When Marie and her daughters arrived in New York, a crowd of journalists, photographers and cameramen were waiting for her.Footnote 22 In this new world, ‘Mme. Curie’ was ‘to end all cancers’, as the New York Times headline claimed upon their arrival.Footnote 23 But there was more for the media: ‘although visibly ill, the unassuming, motherly-look scientist posed for a battery of twenty-six photographers’.Footnote 24 The symbol of hardship and devotion created by Meloney was now real: the ‘motherly figure’ dressed in ‘black’ had arrived in the USA.Footnote 25 From this moment on, Marie Curie became more than a headline, and more than an image of womanhood, suffering and salvation: she was now the physically frail embodiment of radioactivity.

While the Radium Fund campaign meant to refashion cancer therapy in the context of a successful media campaign, it also reshaped state relations in that the US administration wished both to assist and to benefit from assisting the Curie's activities in France. On 20 May, President Harding finally handed Marie her gift at the White House. The gift comprised a key to open a ‘lead-lined casket specially built to contain the [radium] tubes’, ‘so precious’ that these were left safe in the factory.Footnote 26 Marie was welcomed as a ‘symbol’ of the fight against cancer, whilst being surrounded by diplomats and high officials of the magistracy, army and navy, and representatives of the universities.Footnote 27 A gift is a form of diplomatic consensus building: operating through body language, it implies reciprocity and obligation. Indeed, historian Maria Rentetzi, among others, sees gifts as constituent elements of diplomacy that usually come ‘with strings attached’. If the US was to give Curie a gram, she was to give back salvation to the world.Footnote 28

This gift certainly required complex negotiations between Melony, Curie and the US government. Since radium was cheaper in Europe, Melony would have preferred to give Curie money; Curie, on the other hand, was both unwilling to accept cash and anxious that the radium be designated for her own personal use, not for the University of Paris. While she reversed this position on the very evening of the donation ceremony at the White House, her stance still hindered the US government's attempt to position itself as a global benefactor for radium research. These divergent diplomatic interests meant that the gift-giving had to be carefully staged.Footnote 29

The mediatic making of Marie Curie in 1921 had delicate implications for cancer campaigns too, especially given the ASCC's response to sensational claims regarding treatments. The ASCC started as a small organization in New York in 1913, formed by an elite of medical men and philanthropists committed to raising awareness of the importance of cancer prevention to the medical community and the public, throughout the US and also in Canada.Footnote 30 After the First World War, with the help of a new chief executive experienced in health education campaigns against venereal diseases, the society expanded its outreach activities.Footnote 31 Unlike other diseases, cancer was an unpredictable killer. Thus, by all available means – pamphlets, bulletins, posters, radio broadcasts, exhibitions and film – the ASCC repeatedly stressed that cancer's real cure was prevention and therapy. Through surgery, radium and x-rays, cancer could be defeated if diagnosed in time.

Hence the society needed to reframe the sensationalism over Marie's US tour in order to preach caution. Its response aligned to a nascent transnational network between the US and France aimed at increasing radium research whilst publicly managing expectations of cancer therapy. In June, the ASCC's bulletin ends with a note clarifying their stance regarding ‘MME. CURIE’.Footnote 32 For their part, ‘while some rather sweeping statements regarding radium treatment were attributed to her by overzealous news-writers’, Curie's true position was ‘one of sane, but hopeful conservatism’.Footnote 33 For ‘radium has its limitations’ in the treatment of cancer, but one could have ‘faith’ that pure ‘scientific studies with the gram of radium’ could ‘perfect’ its use in this field of therapeutics.Footnote 34

While for the general press Marie was a symbol of the search for a cure for the disease, to the ASCC she thus embodied scientific expertise, which was also of significance to the US radium industry. The company that produced Marie's gift was one of the most successful radium companies in the USA, the Standard Chemical Company. Radium represented innovation and business, and not only research or therapeutics.Footnote 35 During her tour, Marie took the opportunity to visit the company's facilities in Pittsburgh and Canonsburg, even as she declined several other public invitations due to exhaustion. By visiting the company that had produced her gram, Curie helped to advertise and legitimize US radium industries, in addition to playing the role of (mediatized) figurehead in the campaign against cancer.Footnote 36

This exposure was necessary also because at this stage the press disputed the merits of cancer treatment. In 1921 the New York Times published a chronicle about the ‘story of radium’, casting doubt on radium as ‘panacea’ in the treatment of cancer.Footnote 37 The ASCC's bulletin agreed, therefore, to avoid mentioning Marie's visit to the plants of Pittsburgh and Canonsburg, and mentioned instead ‘the large number of honorary degrees’ offered to Marie on the occasion of her stopovers at numerous universities and colleges across the country, to play down these doubts and play up instead her scientific merits.Footnote 38 If it was true that Marie Curie herself could not ‘end all cancers’, she could portray the fundamental role that expertise was to play in a country that wanted to prioritize and commercialize radium research. Moreover, for the society, this was a visit with diplomatic ambitions, the memory of which would not only remain ‘with her, with her two daughters and with the American public forever’, but also ‘serve as another link binding together the aspirations of the two greatest republics in the world’.Footnote 39

On 30 October 1929, Marie Curie would travel again to accept another ‘gram’ at the White House. This time it would be from President Hoover, and would be intended for Marie's second institute in Warsaw (Poland). However, this time she accepted a $50,000 check instead – a dramatic shift from the symbolic apparatus performed in 1921 to camouflage complex negotiations around questions of exchange value and scientific property. Following the meeting with Hoover, Curie avoided any public appearances, but agreed to attend the ASCC's annual dinner as guest of honour. On this occasion, to raise ‘interest in the early diagnosis and proper treatment of cancer’, Marie prepared a speech that was read by a member of the ASCC's finance committee and subsequently broadcast on radio.Footnote 40 In addition to expressing her gratitude for the ASCC's accomplishments in cancer prevention, the scientist took the opportunity to stress that radium absolutely required expertise, for it was really ‘dangerous in untrained hands’.Footnote 41

Publicly, radioactivity progressively meant more than Curie's image of womanhood and scientific purity. Radium became an element that could save but also kill, and the health impacts of which affected Marie too. She died in 1934 at the Sancellemoz sanatorium, from aplastic anaemia, with her daughter Ève at her bedside. Her ‘bone marrow did not react [to the treatment against anemia], probably because it had been injured by a long accumulation of radiations’, wrote Ève in the chapter of Madame Curie dedicated to her mother's death.Footnote 42 At the time, the New York Times also paid a tribute to the scientist: ‘Mme. Curie is dead; martyr to science’ – ‘end hastened for co-discoverer of radium by the effects of accumulated radiations’.Footnote 43 The New York Times used the exact same words later used by Ève in Madame Curie. Marie's anaemia ‘was hastened by what her physicians termed a long accumulation of radiations’ which affected her reaction to the disease.Footnote 44 Likewise, the biography took the opportunity to explain that Marie was aware that radioactivity was a dangerous presence at work, for she ‘had always severely imposed’ precautions on her pupils – yet she was less vigilant with herself.Footnote 45 Ève's tone was cautious, for the young Curie was well aware of how delicate it was to bring the subject of the perils of radium into the public light. But with her mother's death, Ève and her biography were poised to undertake an enhanced role in mediating cancer campaigns, and also to provide a new visual diplomacy dimension for radium-based treatments, this time extending to Portugal.

Building an international alliance in the fight against cancer through images

On 11 January 1938, the Women's Field Army of the ASCC organized a tribute to the memory of Marie Curie, led by the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the recently re-elected US president. ‘A special bound edition’ of Ève Curie's Madame Curie was given to the chargé d'affaires of France, Jules Henry, at the French embassy.Footnote 46 The event was caught on camera, providing a new visual dimension to the diplomacy of radium, honouring Marie Curie through the symbolic representation of her daughter's biography, (re)presenting the long-lasting state support for the Curie's activities, this time from Eleanor Roosevelt.

Figure 4. A tribute to Marie Curie from a group of distinguished women representing the hundred thousand members of the Women's Field Army of the ASCC who presented a specially bound edition of the biography of Madame Curie to Jules Henry while Mrs Roosevelt, wife of the president, looks on, 1938. Photographer: Harris & Ewing. ©Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Washington DC.

Madame Curie was a curious gift to offer to a French representative, especially one who was about to return to Paris to take over the American Section of the French Foreign Office.Footnote 47 Meloney had persuaded Ève Curie – by then an aspiring writer and journalist – to write just the biography following Marie's death.Footnote 48 Finally published on November 1936, an English translation appeared two years later, which could explain why Henry received a special edition of the book. The gift implied a symbolic exchange in the fight against cancer between the two countries. In return for the gifting of the special book edited by the US government, Henry praised the fight that ‘American women are making against cancer’ on behalf of the French administration, and assured the delegation that the ‘French women would join in the cause you have so well begun’.Footnote 49

Pictured together with representatives of ‘the two greatest republics of the world’, and backgrounded by the activity of the women spreading the message of cancer prevention across the US, the gift reframed the collaboration in the fight against cancer between the US and France that had been initiated with Marie Curie's visit in 1921. It (re)presented state involvement in this fight, this time through the first lady Eleanor Roosevelt – all the more significant given the Roosevelt administration's creation of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1937. Part of the New Deal acts, the NCI was established to support and enhance cancer research. Historian James Patterson argues that its formation was a result of ongoing pressure for public action, including from ASCC representatives.Footnote 50 Also involved was the ASCC's Women's Field Army, created in 1936. Their work accelerated in the months prior to the passing of this legislation, and was featured in popular magazines such as Life and Time.Footnote 51

In 1938, the widely photographed book gift to Jules Henry displayed US awareness of the need for renewed support for international cancer collaboration, especially with France, but also the need for domestic backing at a time when trust in radium-based cancer treatments was at stake. Through the gift of Ève's biography, the ASCC (re)presented Marie Curie as an image of expertise, but one that was now attentive to the risks of radioactive exposure. The French government would follow this cautious agenda, but France was not the only country to combine radium-based treatment with protections against the risks of radioactivity. Portugal also was very much aligned with the ASCC's programme, and a member of the French-based International Union against Cancer. As such, the picture of Jules Henry becomes essential to understanding Ève's next diplomatic journey. The young Curie would act not only as a reminder of Marie's expertise, but also as a symbol of this international cancer cooperation, whose public outreach was to be further enhanced and institutionalized on a national basis.

Along with other fascist regimes that emerged in interwar Europe, the Portuguese dictatorship of the Estado Novo was an authoritarian and repressive state, continuously using control and censorship practices as well as propaganda as tools of governance. Moreover, the regime's nationalism was presented as the alternative to the crisis allegedly caused by the constitutional monarchism and republican liberalism of the past. Despite its traditional conservative outlook, the Estado Novo wished to be perceived nationally and internationally as scientifically and culturally modern.Footnote 52 Nor was it indifferent to international appeals coming from non-authoritarian and modern states, such as France and the US. The visit of Ève Curie to the IPO thus offered an opportunity to present Portugal as a modern state with diplomatic ambitions at the onset of the First World War.

This followed months of campaigning through the IPO's bulletin about the now much safer radioactivity treatments. In the aftermath of Curie's death, researchers on both sides of the Atlantic increasingly found themselves having to manage public concerns about radioactivity. For example, two months after the issue of the bulletin that announced Curie's death, the IPO had to allay fears about the building of the Radium Pavilion where radioactive materials for cancer treatment would be stored.Footnote 53 In other instances, the bulletin addressed these fears in a more general tone. In 1938, a French article, translated into the bulletin as ‘X-Rays – source of life and death’, commented on the way in which the general press described the deaths of radiologists as ‘martyrs of science’.Footnote 54 Following the new measures taken in radioactive manoeuvring, the article contended that these ‘saints’ who died saving others were remnants of past times – times when neither the consequences of radioactive exposure were known, nor proper protective measures were taken.

Marie Curie's death also represented an opportunity to propel the international cancer campaign that French and US authorities had started in the previous decade, and extend it to Portugal, with a renewed awareness of the risks of radioactivity. In response, the IPO's bulletin called attention to national and foreign investments applying new protective measures for medical and patient safety in the use of radium-based cancer treatments. The year 1938 was also marked by the International Week against Cancer, organized by the International Union against Cancer. Established in 1933 by the French physiotherapist Jacques Bandaline and the founder of the French League against Cancer, Justin Godart, the union linked several countries, including the US and Portugal.

In November 1938, the programme of the International Week against Cancer was to celebrate those who had developed the most infallible weapons that, together with surgery, could prevent and treat malignant tumours: Pierre and Marie Curie.Footnote 55 Circulated to its membership, the union's guidelines for potential commemorative events included the participation of state officials of each country, the organising of fundraisers, scientific lectures and radio broadcasts, the display of posters and the screening of films. A Curie Day was one of the programme's highlights.Footnote 56 On this occasion, held in Lisbon on 23 November 1938, the IPO presented the film Romance of Radium, produced by Hollywood's Metro–Goldwyn–Mayer. This event was advertised in the press, and it was later reviewed in the pages of the IPO's bulletin.Footnote 57 This short documentary, directed by Jacques Tourneur, was shown at São Luiz theatre with an introduction by the chemist Charles Lepierre and in the presence of the president of the Portuguese Republic and other officials from the Estado Novo regime, as well as French, German and Polish ministers.Footnote 58 In the documentary's final scene, while the radioactive substance is pictured, the voice-over declares that this ‘precious cargo’, arriving in a ‘custom-built limousine’, is handled ‘with more care than Hollywood's most glamorous movie queen’.Footnote 59

The advance of US film culture in Portugal during the establishment of the Estado Novo is notable here. In the late 1930s, film ‘was the United States’ most widely circulated commodity’ and Portuguese history corroborates this, attesting to a wide array of Hollywood producers and films in the country's theatres, cinemas and magazines, as well as in schools and other educational contexts – such as the International Week against Cancer.Footnote 60 Thus it comes as no surprise that feature films, such as Blonde Venus (1932), made their way into Portuguese cinemas. This film contributed significantly to raising awareness of the drawbacks of radioactivity treatments on the European side of the Atlantic. It stars the celebrated Marlene Dietrich as the wife of commercial chemist Ned Faraday (Herbert Marshall), who suffers from radium poisoning, compelling her to return to cabaret life to finance the expensive treatment that her husband needed.Footnote 61 Two years after the screening of the Romance of Radium in Lisbon, Ève Curie herself arrived in the city as a sort of ‘movie queen’.

The ‘filmed’ picture of Ève Curie at the IPO

On 8 January 1940, Ève Curie featured in the ‘Illustrious traveller’ section of the Portuguese newspaper Diário de Lisboa. She was greeted as ‘someone with the most remarkable scientific inheritance of our time’, but also someone who had published a ‘masterpiece’ about ‘one of the most important chapters of modern science’ – the careers of the Curies.Footnote 62 During her stay, she was invited by Warnier to visit the historical sites of Estoril and Sintra. In the afternoon, after a stop at the Jerónimos Monastery, Ève visited the IPO.Footnote 63 On this occasion, the press explained how she went to see the place which stored ‘the three grams’ of ‘the precious metal discovered by her parents’.Footnote 64

Likewise, the IPO's bulletin announced under Ève's picture that the institute did not want ‘the daughter of the radium discoverers’ to miss the opportunity of visiting ‘the establishment where curie-therapy is a standard method of treatment’ – the Radium Pavilion.Footnote 65 Designed by the modernist architect Carlos Ramos, this was the first European facility created to follow the safety directives established in Stockholm's II International Congress of Radiology of 1928, something Francisco Gentil eagerly advertised in multiple publications. The contribution of Salazar to this assignment was not only frequently publicized but actually emblazoned in the pavilion's atrium, for Salazar had made available the funds to solve this urgent problem.Footnote 66 As Gentil conveyed to Salazar at the time, the health of its staff, especially its chief radiologist, Bénard Guedes, was at high risk if radium-based cancer treatments were to continue without proper protection.Footnote 67 Therefore the Radium Pavilion was launched in 1933 with a lead safe at least five centimetres thick to store radium, and with walls to filter the radiation sources with a structure that combined barite mortar, reinforced concrete, cork and cement plaster. Also, all staff were to wear lead protection for the trunk and limbs when manoeuvring radioactive devices.Footnote 68

The presence of Ève Curie highlighted the international expertise of the Radium Pavilion, for she was both ‘the daughter of the radium discoverers’ and their biographer. In the bulletin, alongside her reproduced photograph, the biography Madame Curie was presented as an ‘exact’ depiction of Marie Curie's devotion to science and to the world. Marie had left something both ‘severe and radiant’ behind: ‘RADIOACTIVITY’ – quoting the very conclusion of Ève's biography.Footnote 69 In the end, the reproduced photograph of Ève at the Radium Pavilion with Warnier, Gentil and Guedes embodied more than the IPO's international expertise and official support. Ève represented a renegotiated picture of radioactivity, in which this ‘severe and radiant’ element was safely contained.

Ève Curie's visit to the Radium Pavilion was an act of public scientific diplomacy, represented and translated across various media, with different but complementary agendas. In the bulletin, the reproduced picture of Ève meant to publicize the IPO's accomplishments in making radium available for treatment while minimizing risk, whilst asserting the non-‘peripheral’ location of Portugal in relation to the international milieu. Promoting these accomplishments had the effect of underlining Salazar's Estado Novo's eager cooperation with other countries in the fight against cancer, attesting to their cordial relations – especially in Jornal Português. The relationship between Salazar and Gentil was one of mutual interest. On the one hand, the IPO was given priority in matters of public sponsorship, even if integrated in a long (Western) tradition of a welfare state mostly dependent on local sources, charity and philanthropy. On the other hand, the IPO's dynamism was used to promote the Portuguese regime's scientific and technological modernism abroad and at home. In 1937, the IPO had been already mentioned in the Portuguese Pavilion at the International Fair of Paris. Some months after the visit of Ève Curie, the IPO launched its 1st Propaganda Exhibition, coinciding with the ASCC's programme as well as the ongoing celebrations of the Estado Novo of 1940, which commemorated two historical dates – the founding of Portugal in 1140, and independence from Spanish rule in 1640.

Indeed, the year 1940 was marked by a boom in state-sponsored advertising activities, organized by the Estado Novo's SPN (National Propaganda Secretariat). These culminated in A Exposição do Mundo Português, a large-scale exhibition monumentalizing the regime's nationalism, modernism and imperialism in Belém (Lisbon), from June to December 1940. Jornal Português was also a major contributor to this agenda. In 1940, the number of features produced for this newsreel increased substantially in comparison to previous years. For the most part, these combined the display of political and cultural events and edifications of national interest with international news – mostly in relation to the course of the Second World War – but also episodes of cultural and scientific interest, such as Ève Curie's visit.

In film, Ève Curie served the nationalistic project of Salazar's Estado Novo, the sponsor of the modernistic edification of the Radium Pavilion. Furthermore, the Jornal Português added a new visual dimension to this diplomatic event by choosing to include in the picture the young Curie's departure from Lisbon. Jornal Português's inclusion of Ève's embarking on the liner Vulcania to the US meant to further advertise, at the conflict's outbreak, Portuguese neutrality, already announced in 1939.Footnote 70 This media coverage contributed to presenting Portugal as a safe gateway for those coming in and out of Europe.Footnote 71

Portuguese historians have repeatedly argued that Portugal's neutrality was essential to the Estado Novo's legitimacy (and survival) in the aftermath of the war, securing historic alliances with Great Britain, Spain and Germany, protecting its economy (e.g. exporting wolframite mostly to Britain, but also to Germany), its sovereignty in the Iberian peninsula, and its colonial empire.Footnote 72 Moreover, the economic and social harm brought by the First World War, during the Republican years, was often put forth by Salazar as reason for its neutral position. In the end, the fact that Marie and Pierre Curie's daughter ended up instrumentalized by this agenda further demonstrates that her visit to the IPO was a successful diplomatic operation. It tied the promotion of the Curies’ radiotherapy with Ève's campaigning for peace during World War II, complementing Salazar's position of neutrality, without compromising the networks built upon the visual diplomacy of cancer therapy.

In fact, after the outbreak of the war, the French information commissioner (commissaire général à l'information), Jean Giraudoux, appointed Ève Curie head of his office's women division. Upon her arrival in New York, Ève progressively incorporated the topic of ‘French women and the war’ into her lectures (initially) about Madame Curie. This topic also featured in Time magazine. One article declared, ‘Peace will not come soon, she said, and it will not come at all while the Hitler regime remains in Germany – because the French are determined that when this war ends there will be no more fighting in Europe for a long time.’Footnote 73 There is still much to learn about Ève's enterprise during the war, which eventually led to her appointment as special adviser to NATO's secretary general in 1952. But also worth further investigation is Ève's positioning with regard to Salazar's regime. The Musée Curie archives show that there was at least an interest on her part in learning more about Salazar following her Lisbon detour.Footnote 74 Her correspondence with the French delegation in Portugal shows that the University of Lisbon scheduled a conference about Madame Curie for her return from the US. She planned for an interview with the Portuguese women's magazine Ève while still in the US, to be followed by a conference concerning ‘French women and the war’ at Lisbon's National Theatre.Footnote 75 She did not chair those scheduled conferences – apparently because she could not leave the US in time.Footnote 76

Conclusion

This article has used two mediatic events to explore different aspects of the visual diplomacy of cancer treatment, showing how the persona of Ève Curie, the heir of her parents, translated across different media, and aimed at multiple agendas – often complementary and codependent. In particular, Ève Curie's 1940 visit to the IPO's Radium Pavilion was meant to publicize Portugal's modernist stance as a means to strengthen its international and domestic relations. In film, Ève's feature in the newsreel Jornal Português, commissioned by the Estado Novo's SPN, was used to disseminate this modernist agenda of the regime across national theatres, whilst asserting the non-‘peripheral’ and neutral position of Portugal after the outbreak of the Second World War, and the ongoing cordial relations with the US and France. She was also photographed with the intention of further reproduction in the IPO's bulletin. Within the latter's cancer prevention strategy, the reproduced picture of Ève embodied the overlap of two agendas: fostering international scientific and official collaboration on cancer research and prevention, and publicly promoting radium-based cancer treatments as effective against cancer, and safe from risk.

I have argued that the visit of Ève Curie to the IPO was an act of public scientific diplomacy, the last act in a series of events that began with Marie Curie receiving a gram of radium at the White House in 1921, followed by the bestowal of a copy of Madame Curie on Jules Henry at the French Embassy in Washington in 1938. As the daughter and biographer of a Nobel Prize-winning duo, Ève had a significant contribution to make to public life. But, in contrast with her mother, this contribution was made mainly through her mediatic image. Ève's personal trajectory as a biographer entered the public realm through new photographic and film-based media channels, and was progressively mediated in international cancer campaigns in order to effectively convey messages about the nature of transnational collaborations.

This progressive mediatization of science, as argued here, strongly impacted the way cancer campaigns came to mediate the Curies’ legacy over the years. Rather than meaning a cure for cancer, the Curie name came to be associated with international cooperation, officially validated and communicated publicly. But as much as this media exposure could instigate diplomatic agendas, it could also obstruct them, leading the public to understand that there is an unpredictable side of science – or of radioactivity, in this case. The impacts of the perils of radium, both inside and outside the realm of science, needed to be treated carefully by ASCC officials in their campaigns. When the French citizen Jules Henry was given a copy of Madame Curie by a committee of American health activists, in a ceremony amply covered by the general press, the ASCC publicly and visually endorsed international collaboration and state support, whilst promoting a book in which the depiction of Marie Curie acknowledged the health impacts of radioactive exposure.

Portugal was a later addition to the international alliance uniting France and the US through images that drove the work to further modernize the fight against cancer. Ève Curie's visit helped the IPO to restore confidence in cancer treatment domestically, at a time when the dangers of radium had received significant media exposure. In particular, her visit worked at various levels to raise awareness about the current work against cancer, as well as the legacy of this work, symbolized by the writing of her mother's biography, and the campaigns associated with its publication. More to the point, the US government's gifting of Curie's biography to a French envoy symbolically worked as a diplomatic tool to strengthen an international partnership against cancer that now extended to Portugal. In this way, multiple agendas, ranging across different media, continuously impacted one another and shaped and reshaped the public picture of radioactivity, photographed and filmed at the IPO's Radium Pavilion in 1940.

Photography and film framed the young Curie simultaneously for different contexts, though mainly to legitimate the IPO's international vitalism as a flagship in the consolidation of the Estado Novo. Moreover, Jornal Português chose to include in this depiction Ève's departure from Lisbon, attesting to the regime's neutral position during the war and promoting Portugal as a safe gateway to Europe. It also opened a channel to the consumer culture advancing from the United States – as argued here in relation to cinema. Finally, Ève's appearance in this newsreel proves that the Curies’ legacy not only was scientific, but also had key political and diplomatic resonance. Their daughter's visit to the Radium Pavilion was a diplomatic operation, visually promoting and shaping public perception about the benefits of radium-therapy, whilst mediating and managing international affairs concerning both Ève's and the Estado Novo's positioning with regard to the Second World War.

In the end, Ève's diplomatic agency rests with the photographs and film stills displaying her and her literary work, as the living token of radium discoverers Marie and Pierre Curie, each aspect of her life mediating the effects of that ‘inheritance’. The impact that Ève's images produced in their beholders resonates with the views of theorist William John Thomas Mitchell, who contends that pictures behave as living things, often embodying anxiety over their own image making. Their ‘ghostliness’ or ‘spectrality’ frames them as agents that allow matter to endure in unpredictable ways.Footnote 77 Exactly like radioactivity, images are unstable, ‘severe and radiant’, validating, shaping and affecting others, conscious and unconsciously, through memory and desire.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ana Simões for her valuable supervision and confidence in my work; BJHS editor in chief Amanda Rees, guest editors Simone Turchetti and Matthew Adamson and the anonymous referees for their precious assistance; and Maria Rentetzi for her crucial feedback on the occasion of my PhD's second-year assessment. I thank the Instituto Português de Oncologia, the Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema for assisting and welcoming me into their archives, and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia for granting me a PhD scholarship in 2020 (UI/BD/150759/2020). Finally, I thank my family and friends, especially João Bragança Gil for his continuous support. This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under research project UIDB/00286/2020.