Introduction

Ten years have passed since the comprehensive review of scholarship on Greek architecture by Barbara Barletta in the American Journal of Archaeology (2011). Recent years have witnessed rapid change in the interests of archaeologists and architectural historians along with increasing integration of digital technologies in the daily routine of fieldwork and publication, as illustrated by a volume that I recently co-edited on New Directions and Paradigms for the Study of Greek Architecture (Sapirstein and Scahill Reference Sapirstein and Scahill2020). Here, I will offer a more comprehensive review of the scholarship from the last decade.

A fundamental question is what we mean by Greek architecture. The field has been reacting nimbly to institutional and other external pressures by diversifying and reshaping itself as an increasingly interdisciplinary subject. As a result, we should incorporate a broader range of scholarship ‘about’ Greek architecture than we might have a generation ago. How might we define the discipline in its current state?

First and foremost, this review focuses on architectural research that engages seriously with the material remains from the ancient Greek world (see ‘Introduction’ in Sapirstein and Scahill Reference Sapirstein and Scahill2020). Analyses of ancient literature and inscriptions that are concerned with design and building practices are still essential to the discipline, but purely theoretical work will not be systematically examined here.

Second, I depart from other recent syntheses on Greek architecture that concentrate on the Archaic through to the Hellenistic periods (Miles Reference Miles2016) and, in doing so, retain the origins of Greek architecture as a branch of Classical, and specifically text-oriented, archaeology. The materialist emphasis adopted here points to a broader chronological range, extending to Bronze Age architecture, whose ruins still populate the landscape of Greece and profoundly impacted the development of Classical architecture. Placing an ‘end’ to Greek architecture is problematic. In keeping with the usual understanding, I have set the Hellenistic era – more specifically the middle of the first century BC – as a historical cut-off point, even if substantive changes were already underway in Late Classical Greece with the rise of despotic regimes in Caria and Macedonia. Nevertheless, the imperial architecture from late Hellenistic Greece changed significantly after the arrival of new building technologies and types from Rome.

The geographical range is also problematic. The movement of Greeks throughout the first millennium BC has left us with remains of ostensibly Greek monuments in the territories of dozens of modern nations. Since we seldom know the ethnicity of the people who built in this manner, in most cases Greek architecture is defined by the methods of culture-historical archaeologists – i.e., through the characteristics of its design and execution, such as the classification of a block as a triglyph, or of a building complex as a theatre. The limits of this set of architectural approaches and tastes are fluid and expanded over time, eventually to encompass much of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Methodology

In the ensuing narratives, I will focus on the literature published in the past five years (2017 and later), while summarizing trends in scholarship for the whole decade by means of quantitative data. A few words on the methods employed here are important for understanding the sources. At the start, I gathered references from two major library interfaces collecting works on Greek architecture, the ASCSA/BSA consortium and the DAI – the latter invaluable for its indexing of individual articles and chapters. A search for entries with appropriate subject keywords since 2012 yielded more than 11,000 results, although about three-quarters could be discarded immediately as non-architectural or post-Hellenistic.

Several additional cuts were necessary to make this project manageable. First, preliminary field reports and unpublished dissertations were removed with few exceptions. Second, chapters from an edited volume have generally been excluded, leaving just the collected volume itself in the tally. This choice reduced the bibliography by more than a third, at the expense of more multi-vocal collective works in comparison to peer-reviewed monographs and journal articles. Third, and probably the most subjective aspect of this process, was my assessment of the roughly 1,500 remaining publications, which I retained or removed based on the ostensible degree of engagement with Greek architecture as defined by the above terms. Architectural sculpture, wall-painting, rock-cut tombs, surveys of settlement patterns, and other such topics have been retained only when they also engage explicitly with the built environment.

The final list includes 1,005 entries treating Greek architecture published during the past 10 years at a fairly steady annual rate close to 100. This list is certainly incomplete, not just for the aforementioned choices, but also due to the omission of some books and journals that occasionally publish articles relevant to this study but are not indexed by the ASCSA/BSA or DAI – such as publications with an anthropological or scientific subject, e.g., Journal of Anthropological Archaeology or Quaternary International. The Neolithic and Early Bronze Age have thus been underrepresented, as have numerous studies describing digital recording and visualization techniques. Geographically, there is a modest skew in favour of areas with the longest traditions of scholarship and institutional support – Attica (67 entries), the Peloponnese (109), and Crete (92) – and to a lesser degree the Greek apoikiai in Italy (135). Anatolia, despite its immense area, is not as thoroughly treated (128), while Northern Greece, Illyria, and the shores of the Black Sea are underrepresented (73 in total) – the latter attributable to language barriers and the collecting practices of the ASCSA/BSA and DAI libraries, but also to regional interests on topics besides architecture. The eastern Mediterranean is the least substantively covered in this review (35); recent wars and other political obstacles might be cited, along with the definition of ‘Greek’ architecture adopted here that largely restricts this region to the Hellenistic era. Chronologically, if we classify anything before the Archaic period as prehistory and limit the geographical scope to the boundaries of modern Greece, Bronze Age and Classical architectural studies receive 280 and 572 bibliographical entries, respectively.

Given this immense volume of scholarship completed in the last decade, the following narrative will focus on the major works from the last five years, while mentioning earlier scholarship when appropriate.

Domestic architecture

The radically different structuring of urban areas in the Early Bronze Age Aegean, Minoan Crete, Mycenaean Greece, and Classical Greece have tended to partition the research into self-contained areas with limited interaction. I begin with houses, where there is some potential to find common ground (73 of the 1,005 entries) along with villas and palaces (45).

Two encyclopaedic overviews of Greek houses from prehistory to Late Antiquity (Busana Reference Busana2018) and from prehistory to the present (Kokkinos Reference Kokkinos2018) appear to be the only recent attempts at diachronic integration. The recently published Oikos conference stimulated discourse among specialists in the mainland, Aegean islands, and Crete, but it is limited to the second millennium BC (Relaki and Driessen Reference Relaki and Driessen2020); another conference focuses on early Mycenaean Greece (Eder and Zavadil Reference Eder and Zavadil2021). Most of the bibliography on domestic architecture has been dominated by site reports, where architecture primarily serves as the frame for contextual analysis rather than a topic of study in its own right (e.g., Kaza-Papageorgiou and Kardamaki Reference Kaza-Papageorgiou and Kardamaki2017). A notable exception presents the Early Helladic corridor house excavated at Helike (Katsonopoulou and Katsarou Reference Katsonopoulou and Katsarou2017).

Monumental architecture in the Aegean has been more active (Christakis Reference Christakis2020). Monographs have addressed material issues such as building techniques (Shaw Reference Shaw2015) or latrines and the culture of hygiene (Aufschnaiter Reference Aufschnaiter2018), and two published dissertations have approached questions of social hierarchy through general contextual analysis (Adlung Reference Adlung2020) or through a focus on storage facilities (Kessler Reference Kessler2017). Another book adopts a phenomenological and spatial approach to architectural design and ritual (Palyvou Reference Palyvou2018). The edited volumes on Minoan urbanism (Letesson and Knappett Reference Letesson and Knappett2017), the Aegaeum conference on memory (Borgna et al. Reference Borgna, Caloi, Carinci and Laffineur2019), and papers in the Festschrift for Clairy Palyvou (Tzachili, Arakadaki and Athanasiou Reference Tzachili, Arakadaki and Athanasiou2020) provide diverse interpretative lenses linking architecture to society and meaning.

Excavation monographs have also been published on the architecture of the West House at Akrotiri, Thera (Palyvou Reference Palyvou2019), and at Tavşan Adas (Rechta Reference Rechta2020). On Crete, a monograph has been completed for Palaikastro Building 1 (MacGillivray and Sackett Reference MacGillivray and Sackett2019) and The House of the Frescoes at Knossos (Oddo Reference Oddo2022) along with additions to the excavation series for Haghia Triada (Cucuzza Reference Cucuzza2021), Malia (Schmid and Treuil Reference Schmid and Treuil2017; Devolder and Caloi Reference Devolder and Caloi2019), and Phaistos (Baldacci Reference Baldacci2017). For Postpalatial Crete, recent books examine architecture within the context of domestic and ritual activity at Karphi (Wallace Reference Wallace2020), Mirabello (Gaignerot-Driessen Reference Gaignerot-Driessen2016), and Gortyn (Anzalone Reference Anzalone2015) – the latter tracking signals of urbanization into the Classical period. Recent reports on architectural survey and excavation include Anavlochos (ID8499), Khavania (ID8190), and Zominthos (ID5437); elsewhere in the Aegean, architectural finds have been reported on the Koimisis islet of Thera (ID8151) and Keros-Dhaskalio (ID6626).

Returning to the mainland, an extensive account of the domestic architecture accompanies the final publication of the excavations at Tsoungiza (Mersereau Reference Mersereau, Wright and Dabney2020), and a lengthy article examines the latest phases of occupation at the Lower City in Tiryns (Maran and Papadimitriou Reference Maran and Papadimitriou2021). We may anticipate more scholarship on houses in coming years, including the final publication on the planning and construction of the Mycenaean town at Kalamianos (Fig. 7.1 ), to date discussed in preliminary reports (Pullen Reference Pullen and Gyucha2019); the Middle and Late Helladic settlement at Kirrha (ID8604; Orgeolet et al. Reference Orgeolet, Skorda, Zurbach, de Barbarin, Bérard, Chevaux, Hubert, Krapf, Lagia, Lattard, Lefebvre, Maestracci, Mahé, Moutafi and Sedlbauer2017); and a comparative study of Late Helladic through to Protogeometric houses throughout mainland Greece (Jazwa Reference Jazwa, Sapirstein and Scahill2020). Monumental architecture has nonetheless been driving recent scholarship, with a major new monograph offering spatial analysis and comparative study of the Mycenaean palaces in the Peloponnese (Thaler Reference Thaler2018), along with several contributions to a recent Companion on early Greece (Lemos and Kotsonas Reference Lemos and Kotsonas2020). Books on individual sites include the final studies by the Minnesota Pylos Project (Cooper and Fortenberry Reference Cooper and Fortenberry2017), Iklaina (Cosmopoulos et al. Reference Cosmopoulos, Shelmerdine, Thomas, Gulizio and Brecoulaki2018), and the Mycenaean acropolis at Aigeira (Alram-Stern, Börner and Deger-Jalkotzy Reference Alram-Stern, Börner and Deger-Jalkotzy2020). Beyond urban centres, the AROURA project has published its survey and geophysical analysis of Mycenaean water management in the Copaic basin (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Aravantinos, Horsley and Charami2020).

7.1. Mycenaean architecture at Kalamianos, with a detail showing building Complex 9-IV/VI. © P. Sapirstein/Saronic Harbours Archaeological Research Project (SHARP).

In the historical era, there has been a lull in comparison to the work on houses in previous decades (Barletta Reference Barletta2011: 625–26). However, the final study of the Archaic houses and context material in Chalkis Aitolias has been recently published (Houby-Nielsen Reference Houby-Nielsen2020), along with a conference on Archaic domestic architecture in Magna Grecia (Zuchtriegel and Pesando Reference Zuchtriegel and Pesando2020). A dissertation monograph reviews the architecture at several Classical farmsteads and other rural installations (McHugh Reference McHugh2017). In the field, new urban surveys relying extensively on remote sensing together with focused excavation include those at Molyvoti (ID8120), Morgantina (Kay et al. Reference Kay, Trümper, Heinzelmann and Pomar2020), and Olynthos (Nevett et al. Reference Nevett, Tsigarida, Archibald, Stone, Ault, Akamatis, Cuijpers, Donati, García-Granero, Hartenberger, Horsley, Lancelotti, Margaritis, Alcaina-Mateos, Nanoglou, Panti, Papadopoulos, Pecci, Salminen, Sarris, Stallibrass, Tzochev and Valdambrini2020). Others are examining Classical and Hellenistic centres at Dreros (ID17449) and Pheneos (ID5051). Noteworthy for its locale is a study of remains from the colony Rhòde in Béziers, France (Gomez and Ugolini Reference Gomez and Ugolini2020).

Classical cities

Classical and Hellenistic city planning and monumental public architecture has become a central focus of contemporary research (Barletta Reference Barletta2011: 626–28). Including residences and funerary monuments, nearly half of the reviewed bibliography pertains to secular architecture (420 entries). Given the expanse of the topic, recent monographs have tended to employ comparative analysis of selected, well-studied cities in order to frame the inquiry – as was done for centres in mainland Greece and the Aegean (Tombrägel Reference Tombrägel2017) and pairings of Hellenistic cities in the Levant (Ward Reference Ward2020). Two volumes summarizing current knowledge on the cities of Magna Grecia and Sicily supply the groundwork for future regional studies (Guzzo Reference Guzzo2016; Reference Guzzo2020). The number of conference proceedings framed around topics broadly relevant to Classical urbanism indicate the current popularity of the subject (Caliò and des Courtils Reference Caliò and des Courtils2017; Lamboley, Përzhita and Skenderaj Reference Lamboley, Përzhita and Skenderaj2018; Livadiotti et al. Reference Livadiotti, Pasqua, Caliò and Martines2018; Martin-McAuliffe and Millette Reference Martin-McAuliffe and Millette2018; Trümper, Adornato and Lappi Reference Trümper, Adornato and Lappi2019; Bianchi and D’Acunto Reference Bianchi and D’Acunto2020; De Cesare, Portale and Sojc Reference De Cesare, Portale and Sojc2020; Mohr, Rheidt and Arslan Reference Mohr, Rheidt and Arslan2020; Koller, Quatember, and Trinkl Reference Koller, Quatember and Trinkl2021; Poulsen, Pedersen and Lund Reference Poulsen, Pedersen and Lund2021).

Urban development is central to a number of more focused syntheses and fieldwork reports. At Pergamon, a monograph synthesizing current knowledge of the Hellenistic city has been published by Eric Laufer (Reference Laufer2021), following a challenge to the identifications of several key monuments in the Attalid building programme (Coarelli Reference Coarelli2016a). A conference volume presents new findings at Priene (Raeck, Filges and Mert Reference Raeck, Filges and Mert2020), while another concludes research at the agora at Iasos (Masturzo and Bianchi Reference Masturzo and Bianchi2021). In mainland Greece, notable are the latter two volumes of the Topografia di Atene series (Greco Reference Greco2014a; Reference Greco2014b), and a monograph treating public works and sanctuaries in Late Archaic Athens and Attica (Paga Reference Paga2020). In Sicily, a diachronic overview of Megara Hyblaia (Tréziny and Mège Reference Tréziny and Mège2018) has been followed by a focused analysis of its urban design, water management, and housing in the fourth and third centuries BC (Mège Reference Mège2021).

Civic buildings

The agora and its associated public monuments have attracted several recent studies of the ancient city (Sielhorst Reference Sielhorst2015; with 23 other entries). A recent dissertation monograph reviews current knowledge of public works at urban centres of Epirus (Rinaldi Reference Rinaldi2020), along with an article identifying a common design for meeting halls (Rinaldi Reference Rinaldi2021). Monumental stoas are typically integrated within these analyses, although two are treated individually in final volumes from Megalopolis (Lauter-Bufe Reference Lauter-Bufe2014; Reference Lauter-Bufe2020). A compelling study of ‘unoccupied’ space assesses the significance of deliberately exposed bedrock within Ionian cities (Dietrich Reference Dietrich2016).

Theatres have also drawn much interest, as already observed a decade ago (Barletta Reference Barletta2011: 623–24; with 43 new entries). The most important study completed in this area is the multi-volume Antike Theaterbauten on Greek and Roman theatres (Isler Reference Isler2017). Other synthetic overviews include a dissertation monograph (Gybas Reference Gybas2018) and a recent conference volume (Caminneci, Parello and Rizzo Reference Caminneci, Parello and Rizzo2017). Final volumes document the theatres at Ephesos (Krinzinger and Ruggendorfer Reference Krinzinger and Ruggendorfer2017), Megalopolis (Lauter-Bufe Reference Lauter-Bufe2017), and Phoinike (Villicich Reference Villicich2018). Of many recent articles, those identifying the foundations for periaktoi – revolving devices for changing painted backgrounds (Vitruvius 5.6.8) – at the stage building in Kaunos (Varkvanç Reference Varkvanç2015) and discussing the influence of Dionysiac cult on the theatres of Samothrace (Avramidou Reference Avramidou2022) deserve special mention. More publications on theatres may be anticipated from fieldwork at Kalydon (ID2970), Sikyon (ID11119), Thorikos (ID8498), Thouria (ID15910), and Akragas (Caminneci, Caliò and Livadiotti Reference Caminneci, Caliò and Liviadotti2017; Lepore and Caliò Reference Lepore and Caliò2021).

Less has been completed on baths and athletic facilities in the past decade (19 entries), albeit with some notable exceptions. Following a major review by Monika Trümper (Reference Trümper, Lucore and Trümper2013) are several papers in edited volumes on Magna Grecia and Sicily (Lepore and Caliò Reference Lepore and Caliò2021; Parra and Lombardo Reference Parra and Lombardo2021). Gymnasia are the subject of an edited volume (Mania and Trümper Reference Mania and Trümper2018), papers in several other collective works on related topics (Korres et al. Reference Korres, Mamaloukos, Zambas and Mallouxou-Tufano2018; Raeck, Filges and Mert Reference Raeck, Filges and Mert2020; Koller, Quatember and Trinkl Reference Koller, Quatember and Trinkl2021), and an article about Ptolemaic Cyprus (Stavrou Reference Stavrou2020). Gymnasia have been re-examined at Delphi (ID8606), Eretria (ID12993), and Sikyon (ID15912). The problem of locating and reconstructing elements of the hippodrome have been revisited by comparing cues from ancient texts, topography, and geomorphological data at several sites in Greece (Moretti and Valavanis Reference Moretti and Valavanis2019).

Fortifications

Just over a decade ago, Barletta could write that fortifications had ‘generated considerably less interest’ (2011: 626) than scholarship on other types of Greek monuments. The situation has radically changed, with defensive architecture comprising nearly 10% of the last decade of publication (94 entries). Most of this research has returned to known circuits in order to obtain better documentation and chronology, but walls have become as much a locus for creative interpretative research as any other area of Greek architecture.

Both new documentation and methodologies will be found in the dozens of relevant chapters from Focus on Fortification (Frederiksen et al. Reference Frederiksen, Müth, Schneider and Schnelle2016) and the more theoretically oriented Ancient Fortifications (Müth et al. Reference Müth, Schneider, Schnelle and de Staebler2016), with research to that date reviewed in AR (Fachard Reference Fachard2016). Since then, two conferences have been dedicated to Magna Grecia and Sicily (De Vincenzo Reference De Vincenzo2019; Caliò, Gerogiannis and Kopsacheili Reference Caliò, Gerogiannis and Kopsacheili2020). A dissertation monograph provides a comparative perspective on Mycenaean and Hittite fortifications (Maner Reference Maner2019), and no less than four other books survey walls of the Iron Age, including Archaic Greece (Hülden Reference Hülden2020) and Classical–Hellenistic Arcadia (Maher Reference Maher2017), and two wide-ranging discussions of Greek fortifications and society (Caliò Reference Caliò2021a; Reference Caliò2021b).

Numerous studies from fieldwork undertaken at individual or regional fortifications have been completed. Notable for the Bronze Age are a volume on Mycenaean walls at Ephyra (Papadopoulos and Papadopoulou-Chrysikopoulou Reference Papadopoulos and Papadopoulou-Chrysikopoulou2020) and the excavations at Malthi (Worsham, Lindblom and Zikidi Reference Worsham, Lindblom and Zikidi2018). Four monographs offer diachronic studies of walls in Attica (Lohmann Reference Lohmann2021), Athens (Theocharaki Reference Theocharaki2020), and the Sacred and Dipylon Gates at the Kerameikos (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2017; Gruben and Müller Reference Gruben and Müller2018). Architectural studies of Classical and Hellenistic circuits remain the most numerous, including the treatments of Carian Chersonesos (Held Reference Held2019), Iasos (Cornieti Reference Cornieti2018), and Phokaia (Özyigit Reference Özyigit2017) in Anatolia; Phaistos (Longo Reference Longo2017) on Crete; Chalkis (Dietz and Kolonas Reference Dietz and Kolonas2016) in Aetolia; and Eryx (De Vincenzo Reference De Vincenzo2016), Megara Hyblaia (Tréziny and Mège Reference Tréziny and Mège2018), and Syracuse (Mertens and Beste Reference Mertens and Beste2018) in Sicily. Freestanding towers have been treated as a special category (Lambertz and Ohnesorg Reference Lambertz and Ohnesorg2018; Maher and Mowat Reference Maher and Mowat2018; Dakoronia and Kounouklas Reference Dakoronia and Kounouklas2019). Many other studies are underway, such as at Delphi (ID6888), Kastro Kallithea (ID12959), and Vlochos (ID6788).

The flourishing attention to walls has been aided by the increasing availability and quality of aerial imagery and other topographic data. Together with more extensive 3D recording from the ground – a most impressive example of which was created by the team working at Eleutherai (Fachard et al. Reference Fachard, Murray, Knodell and Papangeli2020) (Fig. 7.2 ) – it has supported new analytical approaches. One question has been how polities established defensive networks within their territory, addressed by means of intervisibility analysis from survey data and terrain models integrated with GIS software (Maher and Mowat Reference Maher and Mowat2018). These studies complement the growing literature assessing the efficacy of walls against changing siege tactics (Scholl Reference Scholl2015; Jonasch Reference Jonasch2020; Eisenberg and Khamisy Reference Eisenberg and Khamisy2021). Two additional questions, which will be revisited below, concern the labour costs of building impressive walls and gates (Taşdelen and Baz Reference Taşdelen and Baz2018; Bessac and Müth Reference Bessac, Müth, Heinzelmann and Recko2020; Fachard et al. Reference Fachard, Murray, Knodell and Papangeli2020; Boswinkel Reference Boswinkel2021) as well as the socio-political implications of their patronage and maintenance (Özer and Taşkran Reference Özer and Taşkran2018; Müth Reference Müth, Sapirstein and Scahill2020).

7.2. Drawing and orthorectified photogrammetric elevation of the north side of the fortress at Eleutherai, with a detail showing the outer face. © S. Murray/Mazi Archaeological Project.

Harbours

Another topic of growing interest has been the study of ancient harbours and port cities (Feuser Reference Feuser2020; Ugolini Reference Ugolini2020; Mania Reference Mania2021; and 38 other entries). Recent publications have demonstrated the various ways in which scientific collaborators skilled in geomorphology, sedimentology, coastline reconstruction, and remote sensing complement the more-established methods of historical, archaeological, topographical, and underwater survey. Mentioning but a few examples should emphasize the rising importance of this aspect of urban archaeology: articles treating Assos (Arslan et al. Reference Arslan, Böhlendorf-Arslan, Mohr, Rheidt, Seifert and Ziemer2018), Kerkyra (Finkler et al. Reference Finkler, Baika, Rigakou, Metallinou, Fischer, Hadler, Emde and Vött2018), Miletos (Brückner et al. Reference Brückner, Herda, Müllenhoff, Rabbel and Stümpel2014), and Rhamnous (Blackman, Pakkanen and Bouras Reference Blackman, Pakkanen and Bouras2021); survey volumes on Carian Chersonesos (Held Reference Held2019) and southern Sicily (Felici, Felici and Lanteri Reference Felici, Felici and Lanteri2020); and recent books on discoveries at Lesbos (Theodoulou and Kourtzellis Reference Theodoulou and Kourtzellis2019) and the port of Amathous (Empereur et al. Reference Empereur, Koželj, Picard and Wurch-Koželj2017). Of specific installations at the port, shipsheds have received special interest, most notably in three recently issued volumes from the surveys and excavation in Piraeus conducted under the aegis of the Danish Institute at Athens (Lovén and Sapountzis Reference Lovén and Sapountzis2019; Reference Lovén and Sapountzis2021a; Reference Lovén and Sapountzis2021b). The development of Cretan harbours and the evidence for Bronze Age shipsheds and slipways at Kommos have been recently debated (Shaw Reference Shaw2019; Shaw and Blackman Reference Shaw and Blackman2020; Mourtzas and Kolaiti Reference Mourtzas and Kolaiti2021).

Greek sanctuaries

Classical sanctuaries, in particular the temple, still dominate the literature on Greek architecture (306 entries, of which 110 examine temples), although they have certainly been yielding ground to the other forms of building discussed above (Barletta Reference Barletta2011: 626–28). The origins of the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian systems were treated in relation to other finely crafted votive objects at Greek sanctuaries in an influential monograph by Mark Wilson Jones (Reference Wilson Jones2014), and, although not yet available at the time of writing, a dissertation monograph by Alessandro Pierattini (Reference Pierattini2022) promises to fill a void left for critical developments during the Early Iron Age. Although the first millennium is the heyday of costly monumental temples, another dissertation reviews Mycenaean sanctuaries in their architectural context (Rousioti Reference Rousioti2018).

The monograph by Mary Hollinshead (Reference Hollinshead2015) on the role of monumental staircases in Greek sanctuaries resonates strongly with recent conferences more generally addressing the subject of movement (Friese, Handberg and Kristensen Reference Friese, Handberg and Kristensen2019; Dromain and Dubernet Reference Dromain and Dubernet2021; Huber and Andringa Reference Huber and Andringa2022). Less common are studies of particular architectural components, once a standard framing in the scholarship (Barletta Reference Barletta2011: 621), although a dissertation monograph examines the polygonal column (Emanuelsson-Paulson Reference Emanuelsson-Paulson2020). Of the many Festschrifts published in recent years, that honouring Manolis Korres has more than a dozen papers treating aspects of sacred architecture, from fine-grained analysis of individual members to broad overviews (Zambas et al. Reference Zambas, Lambrinoudakis, Simantoni-Bournia and Ohnesorg2016), and another is similarly engaged with religious architecture (Partida and Schmidt-Dounas Reference Partida and Schmidt-Dounas2019).

These general overviews, however, are dwarfed in number by new findings from excavation and study at particular sites and regions.

Anatolia

The DAI project at Pergamon has been the most actively published in the previous decade. Three volumes have been added to the Altertümer von Pergamon series: one identifies a heroon in the lower city (Bachmann, Radt and Schwarting Reference Bachmann, Radt and Schwarting2017); another addresses the cult on the eastern grottos (Engels Reference Engels2021); and the third treats the structural remains of the famous altar at the site and Berlin (Klinkott Reference Klinkott2020). The study of the sculpted exterior is ongoing. Lothar Haselberger (Reference Haselberger2020) has addressed the same monument, which he relates to the aesthetics found in the monuments by Hermogenes of Magnesia in a richly illustrated new book.

Proceeding from north to south, Fikret Yegül (Reference Yegül2020) has completed the final study of the Hellenistic and later phases of the temple of Artemis at Sardis, complementing the information gleaned from the modern excavations at the sanctuary (Cahill and Greenwalt, Jr Reference Cahill and Greenwalt2016). Aspects of the religious and secular architecture at Priene are treated in a new volume (Raeck, Filges and Mert Reference Raeck, Filges and Mert2020). The archaeological investigations at Mt Mykale have culminated in three volumes, including an overview of the surveyed architecture (Lohmann, Kalaitzoglou, and Lüdorf Reference Lohmann, Kalaitzoglou and Lüdorf2017), and synthetic studies of the terracotta roof (Lohmann, Kalaitzoglou and Lüdorf Reference Lohmann, Kalaitzoglou and Lüdorf2013) and architecture (Hulek Reference Hulek2018) excavated at Çatallar Tepe, which they identify as a temple and dining hall of the Archaic Panionion. Another Archaic Ionian temple, albeit with a distinctively Anatolian character, has also been published at Phokaia (Özyigit Reference Özyigit2020). New monographs treat the Hekatomnid monuments at Iasos (Masturzo Reference Masturzo2016) and Labraunda (Hellström and Blid Reference Hellström and Blid2019) in Caria.

Black Sea

Excavation and research in Greek centres on the Black Sea coast is underrepresented in the libraries underlying this overview, although recent publications have also tended to focus on non-architectural subjects. Nonetheless, essays concerning monuments from Apollonia Pontica resulted from a collaborative exhibition (Musée du Louvre Reference du Louvre2019), and a monumental Doric structure has been recently reconstructed from spolia in Callatis, Romania (Nistor Reference Nistor2018). For Histria, a summary of past research at the site (Angelescu and Avram Reference Angelescu and Avram2014) and a report on recent work on the acropolis (Angelescu Reference Angelescu2020) are germane here. Roof tiles form the basis for a new study of an Archaic temple at Olbia Pontica (Bujskikh Reference Bujskikh2021), following a general report on the southern temenos (Bujskikh Reference Bujskikh2015).

Aegean

The DAI project at Samos has been the most active in the Aegean. Volumes in the Samos series include the definitive analysis of the prehistoric through to the Early Archaic sanctuary (Walter, Clemente and Niemeier Reference Walter, Clemente and Niemeier2019); another study presents finds and rejects the evidence for buildings formerly assumed to have stood in the southeast area (Kyrieleis Reference Kyrieleis2020). Numerous articles address chronological and topographical issues at the sanctuary and beyond (Zambas Reference Zambas2016–2017; Kienast et al. Reference Kienast, Moustaka, Grossschmidt and Kanz2017; Kienast and Furtwängler Reference Kienast and Furtwängler2018; Niemeier Reference Niemeier2021).

Turning to the Cyclades, much has appeared since the last AR review and an edited volume dedicated to its sanctuaries (Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian2013; Reference Mazarakis Ainian2017; see also the work by Alexandridou and Mazarakis Ainian, this volume). A detailed autopsy and reconstruction of the Archaic temple at Sangri, Naxos, is now complete (Lambrinoudakis and Ohnesorg Reference Lambrinoudakis and Ohnesorg2020). The EfA has issued two new volumes in the Délos series on dedications from the Apollo sanctuary (Herbin Reference Herbin2019) and the Artemis temple (Moretti, Fraisse and Llinas Reference Moretti, Fraisse and Llinas2021). A cultural history of the island has also been published by Filippo Coarelli (Reference Coarelli2016b). A summary of the sanctuaries in Kythnos is now available (Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian2019), and final architectural studies are nearing completion at the sanctuary on Despotiko (ID8509).

On Lemnos, excavations have been undertaken at the Hephaisteion (Di Cesare Reference Di Cesare2019), following extensive architectural restudy. Other architectural monographs analyse the eastern approach to the sanctuary on Samothrace (Wescoat Reference Wescoat2017), and – in its peraia – the Classical temple and altar from Zone (Tsatsopoulou-Kaloudi, Brixhe and Pardalidou Reference Tsatsopoulou-Kaloudi, Brixhe and Pardalidou2015). Research in Crete has been dominated by prehistory, but a new dissertation monograph examines the Classical and later roof tiles from Kato Syme (Zarifis Reference Zarifis2020), and Jérémy Lamaze (Reference Lamaze2019) has recently presented compelling arguments that ‘Temple’ A at Prinias should be reinterpreted as a banqueting hall (see also Kotsonas, this volume).

In Euboea, the ESAG is exploring Archaic and later remains, including rich votive deposits inside the temple at Amarynthos (ID12997; Reber et al. Reference Reber, Knoepfler, Karapaschalidou, Krapf, Greger, Ackermann and André2021). Excavations and survey at Plakari have explored architectural remains of a Classical sanctuary and earlier terracing (Crielaard Reference Crielaard2020).

Greek mainland

Attic sanctuaries remain an important focus for architectural research and publication. New insights into architectural practices continue to arise from the ongoing restoration works on the Acropolis (Lambrinou Reference Lambrinou, Sapirstein and Scahill2020; Manidaki Reference Manidaki, Sapirstein and Scahill2020). More research inevitably involves restudy and synthesis, such as books on the construction of the Parthenon (Marginesu Reference Marginesu2020), the late-Archaic building programme (Paga Reference Paga2020), and case studies of architectural reuse (Rous Reference Rous2019). New conference volumes address the Archaic and Classical sanctuaries and city (Graml, Doronzio and Capozzoli Reference Graml, Doronzio and Capozzoli2019; Palagia and Sioumpara Reference Palagia and Sioumpara2019; Gotter and Sioumpara Reference Gotter and Sioumpara2022). At Sounion in Attica, notable are the final studies of the Athena sanctuary (Barletta, Dinsmoor Jr and Thompson Reference Barletta, Dinsmoor and Thompson2017), and the Archaic predecessor to the Poseidon temple (Paga and Miles Reference Paga and Miles2016).

In the Peloponnese, several final publications have been completed, including a dissertation on how Ionic architecture was variously employed in its monuments (Straub Reference Straub2019) and the culmination of extensive architectural research on the temple of Herakles at Kleonai (Mattern Reference Mattern2015). Two excavation volumes present new architectural material from Agios Elias of Asea (Forsén Reference Forsén2021) and Tegea (Nordquist, Voyatzis and Østby Reference Nordquist, Voyatzis and Østby2014). A temple of Demeter Chthonia has emerged within the fabric of a church at Hermione (Blid Reference Blid2021). The recent publication of the Minnesota Pylos Project has tentatively identified a later temple based on architectural terracotta postdating the palatial era (Cooper and Fortenberry Reference Cooper and Fortenberry2017).

Recent discoveries have been concentrated in Achaia, including impressive new Geometric and Archaic remains from the sanctuary at Trapeza (ID15660; Hellner and Gennatou Reference Hellner and Gennatou2015; chapters in Greco and Rizakis Reference Greco and Rizakis2019) and the sanctuary near Aigeira at Marmara (ID17062: Kolia Reference Kolia, Frielinghaus and Stroszeck2017); recent excavations explored Geometric and Archaic levels at Helike (ID8560). Elsewhere, the excavations on Mt Lykaion integrate architectural studies of the monuments in the Lower Sanctuary (Romano and Voyatzis Reference Romano and Voyatzis2015). Other projects are examining sanctuaries at Amyklai (ID15909) and Thouria (ID8563) – the latter together with secular monuments.

At Olympia, Judith Barringer (Reference Barringer2020) has completed a diachronic cultural history that insightfully dissects the immense literature about the sanctuary architecture. A digital project employed 3D recording to challenge the reconstructions of the peristyle of the Heraion (Sapirstein Reference Sapirstein2016), and the early ash altar and Pelopion have been subject to recent reinterpretation (Leonhardt Reference Leonhardt2018; Romano and Voyatzis Reference Romano and Voyatzis2021). A new review of the evidence recontextualizes early stoneworking in monumental buildings in the Corinthia (Scahill Reference Scahill, Hanberg and Gadolou2017).

In Central Greece, excavations at Kalapodi have expanded to areas beyond the core of the sanctuary, while continuing to shed new light on the Archaic and Classical temple architecture (ID6784; Sporn Reference Sporn2016–2017); a new sanctuary has been excavated at Onchestos (ID6616). The excavations at Thermon have most recently attended to the Archaic through Hellenistic architecture (Papapostolou Reference Papapostolou2021). To the northwest at Dodona, a diachronic study addresses the experience of the sanctuary and its monuments (Chapinal-Heras Reference Chapinal-Heras2021). David Hernandez (Reference Hernandez2017) has recently argued for the existence of an Archaic temple of Athena on the acropolis of Bouthrotos.

Italy

At Greek sites of Italy, the preponderance of recent research has addressed urban and private architecture, but many studies are nonetheless focused on its many sanctuaries. A paper on ‘Sacred Houses’ reviews the evidence for cult in residential areas at multiple sites in Magna Grecia as well as Sicily (Serino Reference Serino2021). In southern Italy, the Chora of Metaponto project has issued several final volumes, most recently on the Pantanello sanctuary and architecture (Carter and Swift Reference Carter and Swift2018). Two books have examined the Archaic and later architectural phases of the sanctuary at Punta Stilo, Kaulonia (Giaccone Reference Giaccone2015; Parra Reference Parra2017).

In Sicily, a review examines the patronage of Hieron II at five centres, including sanctuaries (Wolf Reference Wolf2016). The rich architecture at Syracuse has yet to be subject to final publication, but two recent studies recontextualize the building inscription at Apollonion of Syracuse in light of its impressive colonnades (Di Cesare Reference Di Cesare2020; Sapirstein Reference Sapirstein2021a), and another revisits chronology and the Athena sanctuary (Amara Reference Amara and Jonasch2020). At Akragas, multiple new studies of standing temple architecture and excavations have been recently completed (Cavalier et al. Reference Cavalier, Bernier, Cayre, Bernier, Aylward, Ivantchik and Svoyskiy2020; Santoro Reference Santoro2020); and ongoing research, including work on its sanctuaries, has been presented in numerous loosely structured conferences volumes (Caminneci, Caliò and Livadiotti Reference Caminneci, Caliò and Liviadotti2017; Sojc Reference Sojc2017; De Cesare, Portale and Sojc Reference De Cesare, Portale and Sojc2020; Lepore and Caliò Reference Lepore and Caliò2021). At Selinunte, a new monograph in the DAI series examines altars there (Voigts Reference Voigts2017) and ongoing excavations inside Temple R at Selinunte are providing invaluable stratigraphic recording and cult deposits (Marconi and Ward Reference Marconi and Ward2022).

Technological studies

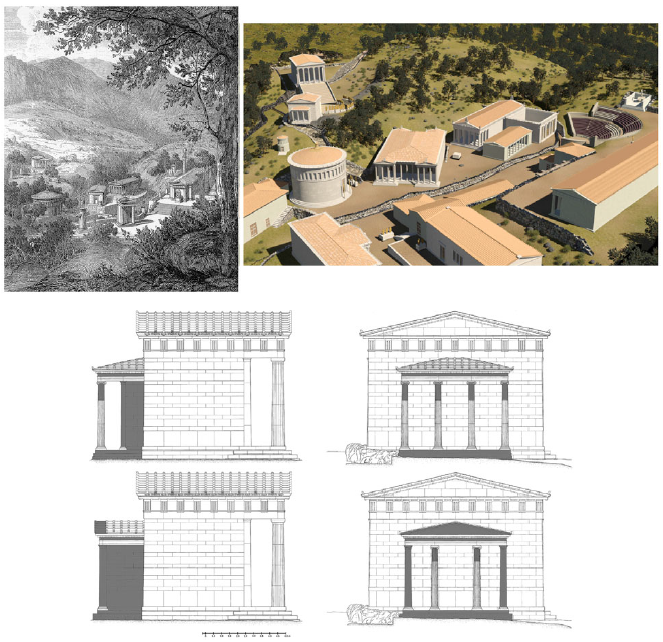

Architectural historians have explored innovative methods for documenting and presenting damaged and lost monuments for more than a century (Vavouranakis Reference Vavouranakis2021). Gaining momentum since the 1990s, one movement has been the computerization of the drawing and reconstruction process. In addition to the reliance on the Total Station in support of field drawings, software has largely replaced the drawing table in the production of illustrations for publication, inviting experiments with 3D software. No longer a niche area, 3D modelling has become commonplace – although certainly not universal – in Greek architectural studies (Parra Reference Parra2017; Pakkanen et al. Reference Pakkanen, Lentini, Sarris, Tikkala and Manataki2019; Santoro Reference Santoro2020; Zarifis Reference Zarifis2020; Part 4 in Sapirstein and Scahill Reference Sapirstein and Scahill2020; Lancaster Reference Lancaster2021). Such models have opened new avenues for research, including the virtual reassembly of fragmentary monuments, modelling aspects of the ancient construction process, and the simulation and navigation of ancient spaces (Fig. 7.3 ).

7.3. Reconstructed views of the sanctuary of the Great Gods, Samothrace, in 1880 and 2017 (above), with two of the viable restorations of the Dedication of Philip III and Alexander IV (below). © American Excavations Samothrace.

A seismic shift has occurred in the area of 3D recording at the site and museum, as the comparatively expensive and bulky equipment for laser-scanning has been eclipsed by automated photogrammetry (Sapirstein and Murray Reference Sapirstein and Murray2017; 17 other entries in the bibliography). Laser scanning has continued to play a role in museum recording, where it is most effective, or in combination with ground and aerial photogrammetric data (Hatzopoulos, Stefanakis and Georgopoulos Reference Hatzopoulos, Stefanakis and Georgopoulos2017; Pakkanen et al. Reference Pakkanen, Lentini, Sarris, Tikkala and Manataki2019; Turner Reference Turner2020). Other recent studies have relied primarily on photogrammetry for the recording and visualization of complex monuments (Sapirstein Reference Sapirstein2016), with remarkable results at the gigantic Thracian tomb of Starosel (Tzochev Reference Tzochev2021) (Fig. 7.4 ). The marked rise of interest in fortifications and other large installations cannot be simply attributed to the rise of 3D recording, but it has certainly been supported by the new availability of the technology (De Vincenzo Reference De Vincenzo2016; Knodell, Fachard and Papangeli Reference Knodell, Fachard and Papangeli2017; Longo Reference Longo2017; Cavalier et al. Reference Cavalier, Bernier, Cayre, Bernier, Aylward, Ivantchik and Svoyskiy2020; Felici, Felici and Lanteri Reference Felici, Felici and Lanteri2020).

7.4. Hypothetical reconstruction of the retaining wall and the propylon of the tomb at Starosel (left), longitudinal section of the interior (right), and unfolded drawing and orthorectified photogrammetric elevation of the tholos (below). © Chavdar Tzochev.

Often complemented by aerial photogrammetric modelling of the topography, remote sensing has also been rapidly gaining ground (Donati et al. Reference Donati, Sarris, Papadopoulos, Kalayc, Simon, Manataki, Moffat and Cuenca-García2017; 27 entries). The results of ground-penetrating radar or magnetometry surveys have been tested by excavation in numerous Greek sites (Sporn Reference Sporn2016–2017; Driessen and Sarris Reference Driessen and Sarris2020), while geophysical data can effectively reveal the plan of waterworks and urban sites (Brückner et al. Reference Brückner, Herda, Müllenhoff, Rabbel and Stümpel2014; Kay et al. Reference Kay, Trümper, Heinzelmann and Pomar2020; Lane et al. Reference Lane, Aravantinos, Horsley and Charami2020; Blackman et al. Reference Blackman, Pakkanen and Bouras2021), individual structures prior to excavation (Malfitana et al. Reference Malfitana, Cacciaguerra, Mazzaglia, Leucci, De Giorgi and Russo2017; Ammerman Reference Ammerman2020), or the interior of massive earthworks such as the Kasta tumulus (Tsokas et al. Reference Tsokas, Tsourlos, Kim, Yi, Vargemezis, Lefantzis, Fikos and Peristeri2018). Of central importance is the management of digital records with GIS software, which several studies have employed to address topographical questions such as site intervisibility (Déderix Reference Déderix2017; Maher and Mowat Reference Maher and Mowat2018).

Materials and provenience analysis

Research on the provenience of stone has been on the rise as well (for example, Russell Reference Russell2016–2017; 34 entries). Despite being dominated by Roman and sculptural material, a good deal of research has examined Greek, in particular Hellenistic, architecture. Recent editions of the Association for the Study of Marble and other Stones in Antiquity (ASMOSIA) conference include papers on Athens, Naxos, Samothrace, Mt Lykaion, and formerly unknown quarries in the southern Mani (Pensabene and Gasparini Reference Pensabene and Gasparini2015; Poljak and Marasović Reference Poljak and Marasović2018).

Significant new findings have arisen through comparison of the petrographic and chemical profiles of local quarries with monuments, revealing when quarries were being exploited by linking them with dated monuments, while distinguishing local from imported stone. The large research programme at Hierapolis has focused on its many Roman remains, but Hellenistic activity has also been clarified in several sites in the region (Tommaso and Scardozzi Reference Tommaso and Scardozzi2016). The combined approach to marble quarries and archaeometry has been effectively employed elsewhere in Anatolia, such as Labraunda (Freccero Reference Freccero2015) and Ephesos (Anevlavi et al. Reference Anevlavi, Bielefeld, Ladstätter, Prochaska and Samitz2020). In Greece, comparisons to known quarry profiles have, for example, suggested a Parian origin for the Eretria temple marbles (Lazzarini, Maniatis and Persano Reference Lazzarini, Maniatis and Persano2019) and identified imported stones at Delos (Vettor et al. Reference Vettor, Sautter, Pont, Harivel, Jolivet, Moretti and Moretti2021) – where an expansive geological study is underway (ID8584).

Another important focus has been on the identification, mapping, and analysis of quarry sites themselves, irrespective of archaeometric sampling. One such project confronted challenging maritime conditions during coastal surveys in Sicily (Felici, Felici and Lanteri Reference Felici, Felici and Lanteri2020); another has documented the methods for stone extraction and block handling at the harbour of Amathous (Empereur et al. Reference Empereur, Koželj, Picard and Wurch-Koželj2017). Routes from the quarry to the site have been underexplored, which makes the recent analysis of a Classical-era track at Delphi a notable contribution to basic knowledge and methodologies (Hansen, Algreen-Ussing and Frederiksen Reference Hansen, Algreen-Ussing and Frederiksen2017).

Other promising avenues for compositional analysis have begun to be explored besides stone (12 entries). First, a pioneering study on the uses and composition of mudbrick walls in palatial Malia identified groupings that appear to correspond to specialized teams of labourers (Devolder and Lorenzon Reference Devolder and Lorenzon2019); preliminary work along these lines has been reported at Kalapodi (Sporn Reference Sporn2016–2017). For fired clays, the research led by Germana Barone on provenience, manufacturing techniques, and artisans who made Archaic architectural terracotta in southeastern Sicily (Barone et al. Reference Barone, Mazzoleni, Raneri, Spagnolo and Santostefano2017; Reference Barone, Mazzoleni, Raneri, Monterosso, Santostefano, Spagnolo and Vasta2018) indicates the rich potential for applying methods – already well-established in ceramology – in a more systematic manner to roof tiles.

Chemical analysis has been central to the past two decades’ work on ancient polychromy, although the focus continues to be on sculpture. Architectural applications, however, include two recent reports on the pigments on blocks of the Parthenon (Aggelakopoulou and Bakalos Reference Aggelakopoulou and Bakolas2022; Aggelakopoulou, Sotiropoulou and Karagiannis Reference Aggelakopoulou, Sotiropoulou and Karagiannis2022), alongside a collected volume expressing the recent interest in studying architectural polychromy through diverse approaches (Saner, Külekçi and Öncü Reference Saner, Külekçi and Öncü2018; Barry Reference Barry2020).

Roofing and architectural terracottas

Studies of architectural terracotta have proliferated notably since the time of Barletta’s review (Reference Barletta2011: 622–23; now 53 entries). The Deliciae Fictiles conference series has continued to foster innovative scholarship on both Greek and non-Greek tiles (Lulof, Manzini and Rescigno Reference Lulof, Manzini and Rescigno2019). Roofs have often been treated in isolation, a traditional division of ceramic from stone that can be found in many of the publications of the sanctuaries surveyed above. Promising are the more holistic approaches to the temples at Çatallar Tepe (Hulek Reference Hulek2018), the plain roof tiles and foundations united by the recent study of Kato Syme (Zarifis Reference Zarifis2020; see also Kotsonas, this volume), a new project re-examining several monuments in Sicilian Naxos (Pakkanen et al. Reference Pakkanen, Lentini, Sarris, Tikkala and Manataki2019), and at Sangri in Cycladic Naxos (Lambrinoudakis and Ohnesorg Reference Lambrinoudakis and Ohnesorg2020) – albeit for a marble roof.

Bronze Age roofing is another dynamic area. An old debate over how Mycenaeans employed fired tiles has been transformed by a rich context excavated in the Kadmeia at Thebes, swiftly published in exemplary detail (Aravantinos, Fappas and Galanakis Reference Aravantinos, Fappas and Galanakis2020). Similar examples have been published from Dimini (Jazwa Reference Jazwa2018–2020), as well as Early Helladic tiles from Mitrou (Jazwa Reference Jazwa2018). On a related front, Joseph Shaw has addressed multistory buildings in Crete (Reference Shaw2016; Reference Shaw2017).

New questions about roofs are being posed beyond their aforementioned potential for compositional analysis. The manufacturing technique has been assessed through macroscopic analysis, with an aim to examine craftspeople through the lens of the chaîne opératoire (Jazwa Reference Jazwa2018; Reference Jazwa2018–2020; Sapirstein Reference Sapirstein and Cooper2021b). The common practice of stamping tiles yields complementary information about workshop organization, as may be observed from recent epigraphical studies in Greece (De Domenico Reference De Domenico2017; Reference De Domenico2021) and a monograph on Selinunte (Conti Reference Conti2018). Others have addressed the meaning of roof decoration from an art historical perspective. In addition to a dissertation monograph on Archaic and Classical acroteria (Reinhardt Reference Reinhardt2018), the symbolism of crowning elements are addressed in diverse contexts from Delphi (Jacquemin and Laroche Reference Jacquemin and Laroche2021) to the Levant (Schmidt-Colinet Reference Schmidt-Colinet2022).

Design, construction, and the life-history of Greek monuments

The issues of design and construction are integral to many of the previous areas of research, cross-cutting era and type – conservatively, 110 of the 1,005 bibliographic entries considered here. However, the traditional focus on architects and monumental temple architecture has been steadily shifting into new areas (Barletta Reference Barletta2011: 628–29; 23 entries). A number of studies engage with architectural writings – two monographs on Vitruvius and Philon of Byzantium should be noted here (Nichols Reference Nichols2017; Santagati Reference Santagati2021) – and related matters of proportion and alignment, building on more than a century of scholarly literature (Kanellopoulos and Petrakis Reference Kanellopoulos and Petrakis2018; Haselberger Reference Haselberger2020; Tanner Reference Tanner, Sapirstein and Scahill2020; Borghini Reference Borghini2021). Inter-site comparison is fundamental to any archaeological analysis, but notable are the number of cross-cultural studies between Greek and non-Greek architectural traditions (Giaccone Reference Giaccone2015; Thaler Reference Thaler2018; Lamaze Reference Lamaze2019; Maner Reference Maner2019; chapters in Lulof, Manzini and Rescigno Reference Lulof, Manzini and Rescigno2019; Trümper, Adornato and Lappi Reference Trümper, Adornato and Lappi2019; Ward Reference Ward2020). Others have applied new methods to old questions concerning the configuration of domestic and palatial architecture (Paliou, Lieberwirth and Polla Reference Paliou, Lieberwirth and Polla2014; Palyvou Reference Palyvou2018; Thaler Reference Thaler2018), the preponderance focusing on social dynamics during the Bronze Age – when a wealth of complex, multi-roomed structures can be analysed and compared in terms of access routes, intervisibility, and related computational approaches to spatial analysis.

What characterizes contemporary research, if anything, is its material turn through scrutiny of architectural members. Such autopsies can reveal the actions of ancient architects and theorists, but they have more to tell us about masons and other common workers at the construction site (39 entries). Recent conferences have invited studies of toolmarks (Kurapkat and Wulf-Rheidt Reference Kurapkat and Wulf-Rheidt2017), ashlar masonry (Devolder and Kreimerman Reference Devolder and Kreimerman2020), repairs (Broeck-Parant and Ismaelli Reference Broeck-Parant and Ismaelli2021), and rough or unfinished workmanship (Papini Reference Papini2019). Similar themes come out from papers in more general collective works (Zambas et al. Reference Zambas, Lambrinoudakis, Simantoni-Bournia and Ohnesorg2016; Frielinghaus and Schattner Reference Frielinghaus and Schattner2018; Sapirstein and Scahill Reference Sapirstein and Scahill2020). Construction diagrams etched into ancient stones reveal an ad hoc approach to construction (Corso Reference Corso2018; Capelle Reference Capelle, Sapirstein and Scahill2020), rather than the execution of a detailed blueprint from the architect’s drafting table. New research has investigated how engineering challenges were solved on site, such as at the Eupalinos tunnel (Zambas Reference Zambas2016–2017), or the geophysical survey and excavations into the foundation platform for the Athena temple at Poseidonia (Ammerman Reference Ammerman2020). Other aspects of the construction process have been gleaned from the unfinished members intended for the Claros temple discovered in the Kzlburun column wreck (Aylward and Carlson Reference Aylward, Carlson, Steadman and McMahon2017), or from the concerted study of an Archaic Ionic capital from Attica (Korres Reference Korres, Kalogeropoulos, Vasilikou, Tivérios and Petrakos2021). Experimental replications have likewise advanced our understanding of the building process: the operation of a Mycenaean saw (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2018), or the handling of Archaic Corinthian blocks (Pierattini Reference Pierattini2019).

Architectural energetics is an important new area occupying researchers of both prehistoric and Classical architecture (Brysbaert et al. Reference Brysbaert, Klinkenberg, Gutiérrez and Vikatou2018; 40 entries). In the past few years, models for estimating labour input have led to new research on: monumental Mycenaean constructions (Turner Reference Turner2020; Boswinkel Reference Boswinkel2021; Pakkanen and Brysbaert Reference Pakkanen and Brysbaert2021); Archaic cities (Fitzsimons Reference Fitzsimons, Rupp and Tomlinson2017) and tiled roofs (Sapirstein Reference Sapirstein and Cooper2021b); and Classical temples (Marginesu Reference Marginesu2020; Patay-Horváth Reference Patay-Horváth, Sapirstein and Scahill2020), quarries (Tommaso and Scardozzi Reference Tommaso and Scardozzi2016), houses (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2021), and fortifications (Bessac and Müth Reference Bessac, Müth, Heinzelmann and Recko2020; Fachard et al. Reference Fachard, Murray, Knodell and Papangeli2020). Epigraphists, too, have contributed to this discourse through the study of building accounts, including chapters in an edited volume (Harter-Uibopuu Reference Harter-Uibopuu2022), a study of seasonality in ancient constructions (Carusi Reference Carusi, Lichtenberger and Raja2021), and reassessments of records at Epidauros (Kritzas and Prignitz Reference Kritzas and Prignitz2020; Lambrinoudakis and Prignitz Reference Lambrinoudakis and Prignitz2020), Didyma (Prignitz Reference Prignitz2019), and Delphi (Lamouille Reference Lamouille2020). Of particular importance to these issues is the study of the walls at Teos and their associated financial texts (Taşdelen and Baz Reference Taşdelen and Baz2018).

We also observe new interest in the changing uses of buildings and the afterlives of their architectural members (Piesker and Wulf-Rheidt Reference Piesker and Wulf-Rheidt2020; 48 entries). Generally consonant with reception studies in the Classics, many studies have assessed the manners of and meanings behind the reuse of Greek monumental architecture. Three dissertation monographs illustrate the range of possibilities: a materially oriented study of the processing of spolia in Late Antique fortifications (Frey Reference Frey2016), the articulation of the theory of upcycling in several cases of Athenian reuse (Rous Reference Rous2019), and an examination of the meaning of destroyed architecture in the text of Pausanias (Schreyer Reference Schreyer2019).

Finally, one of the more intriguing studies on Greek architecture from the last decade is difficult to group due to its intersection with many of the foregoing research areas. Antonis Kotsonas (Reference Kotsonas2018) has offered a cultural history of the Cretan Labyrinth – a monument that never existed except in the imaginations of ancient through to early modern writers.

Concluding thoughts and future directions

Greek architecture is a robust and dynamic field that has engaged hundreds of scholars from a wide range of disciplines. This review’s consideration of all the architectural systems from pre-Roman Greece reveals some important differences in scholarly approach according to the period, region, and type of monument. Most prominent is the longstanding divide between prehistoric and historic archaeologists, in part due to fundamental differences in the kinds of buildings and the training required of specialists in the respective areas, and in part heightened by a tendency to frame collective publications around topics specific to one period at the exclusion of the other. Nonetheless, there is still considerable potential for diachronic study and collaboration through many of the categories of architectural analysis reviewed here, such as the design and uses of houses, cities, fortifications and other territorial defensive networks, or water access and management.

Methodologically, research into Greek architecture of any period or place has become nearly indistinguishable. Current fieldwork routinely integrates remote sensing, 3D recording, digital visualization, and archaeometric analysis in support of architectural and urban studies. The whole discipline shares common interests in cross-cultural comparison, and specialists in prehistoric and Classical archaeology alike are examining ancient construction crews, materials, and technologies with new vigour, employing a wide variety of approaches from the close inspection of worked surfaces to experimental re-enactments and labour estimations. We might expect to see innovative research through additional methodological exchanges among the sub-disciplines, such as applying the approaches to spatial analysis currently popular in Bronze Age architecture to other periods and building types. Likewise, we should encourage more intensive study and inter-site comparison of the monuments in the northern Balkans and Black Sea, Cyprus, and Levant, each of which have great potential to yield new discoveries in comparison to the best-known centres of southern Greece and the Aegean.