Introduction

With a reported prevalence of 6%–25%, penicillin allergy is the most frequently reported drug allergy worldwide. Reference Castells, Khan and Phillips1 However, data suggest that less than 10% of patients with a penicillin allergy label in their medical charts have a true immunoglobulin E-mediated hypersensitivity. Reference Sacco, Bates, Brigham, Imam and Burton2,Reference Macy and Ngor3 Erroneous documentation of penicillin allergy is a public health threat and is associated with receipt of less appropriate alternative antibiotic therapy, increased health care costs, longer hospital stays, development of drug-resistant infections, and increased mortality. Reference MacFadden, LaDelfa and Leen4,Reference Macy and Contreras5 In the United States, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI); the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI); the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have initiated efforts to promote recognition and removal of inaccurate penicillin allergy labels. Several resources are available to assist in the evaluation and removal of penicillin allergy. Reference Shenoy, Macy, Rowe and Blumenthal6,7 In a recent guidance document “Drug allergy: A 2022 practice parameter update,” Reference Khan, Banerji and Blumenthal8 the AAAAI and ACAAI support proactive penicillin allergy delabeling and the use of direct amoxicillin challenge in patients with low-risk penicillin allergy histories (defined as benign cutaneous reactions occurring more than 5 yr ago). Allergy societies outside the United States have endorsed similar approaches, including the important role of non-allergy specialists in delabeling services. Reference Wijnakker, van Maaren and Bode9,Reference Savic, Ardern-Jones and Avery10

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, with approximately 9 million veterans currently enrolled in care. 11 Advancing age and high prevalence of chronic comorbidities increase veterans’ risks of bacterial infections and subsequent need for antibiotic therapy. Reference Richardson, Hill and Smith12 Additionally, the VHA performs over 600,000 surgical procedures annually Reference Rose, Mattingly, Morris, Trickey, Ding and Wren13 for which β-lactams are the preferred prophylactic agents. Reference Blumenthal, Ryan, Li, Lee, Kuhlen and Shenoy14 This magnifies the importance of identifying and removing unverified penicillin allergy labels specifically in the US veteran population.

As infectious diseases practitioners actively involved in penicillin allergy evaluation, the authors conducted a narrative review (methods detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1 and results shown in Tables 1 and 2) on the current state of penicillin allergy within the VHA and addressed ongoing challenges and opportunities for growth.

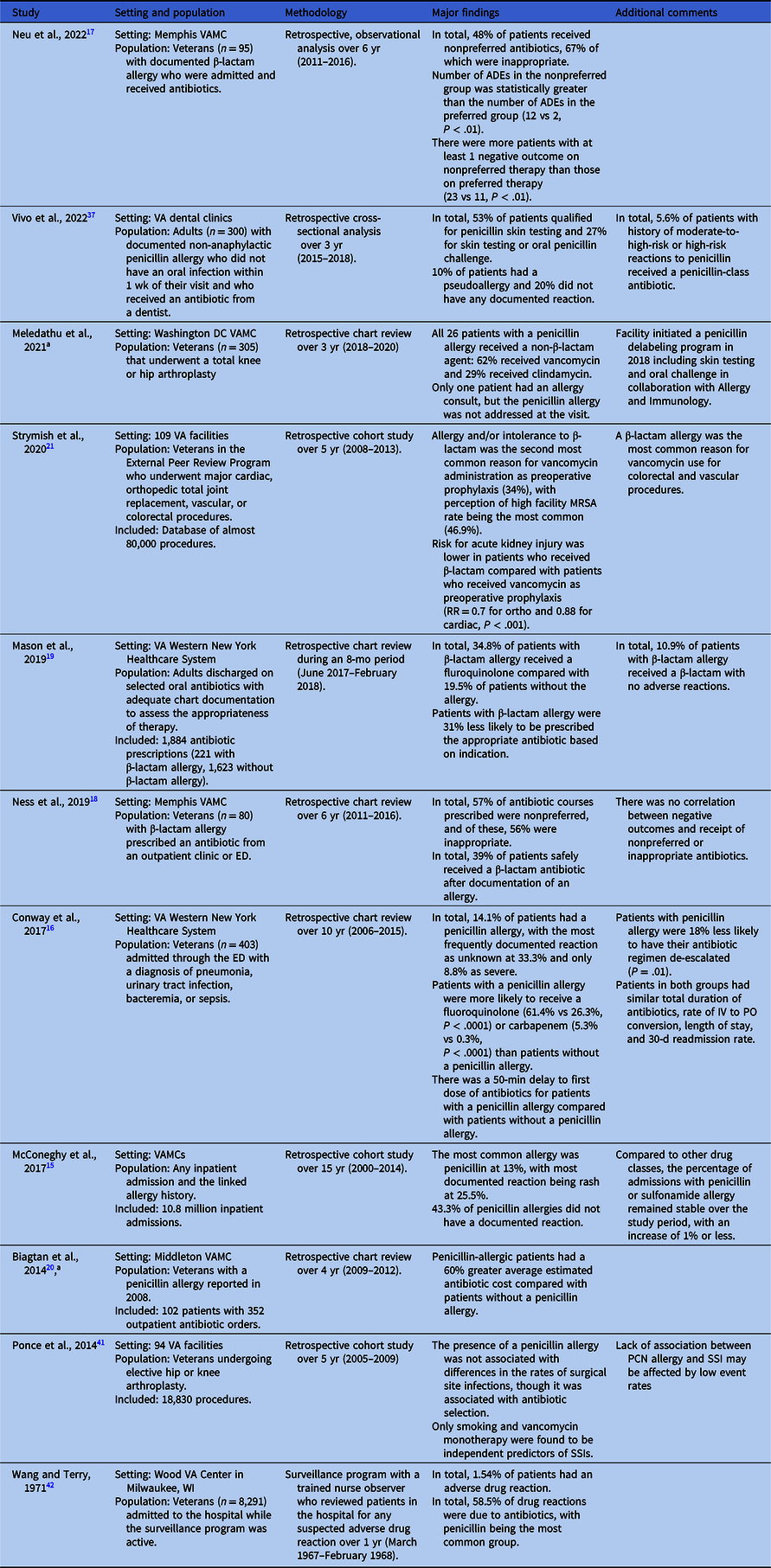

Table 1. Epidemiology of penicillin allergy within VHA

Note. ADE, adverse drug event; ED, emergency department; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; RR, relative risk; VA, Veterans Affairs; VAMC, VA Medical Center.

a Abstract only available.

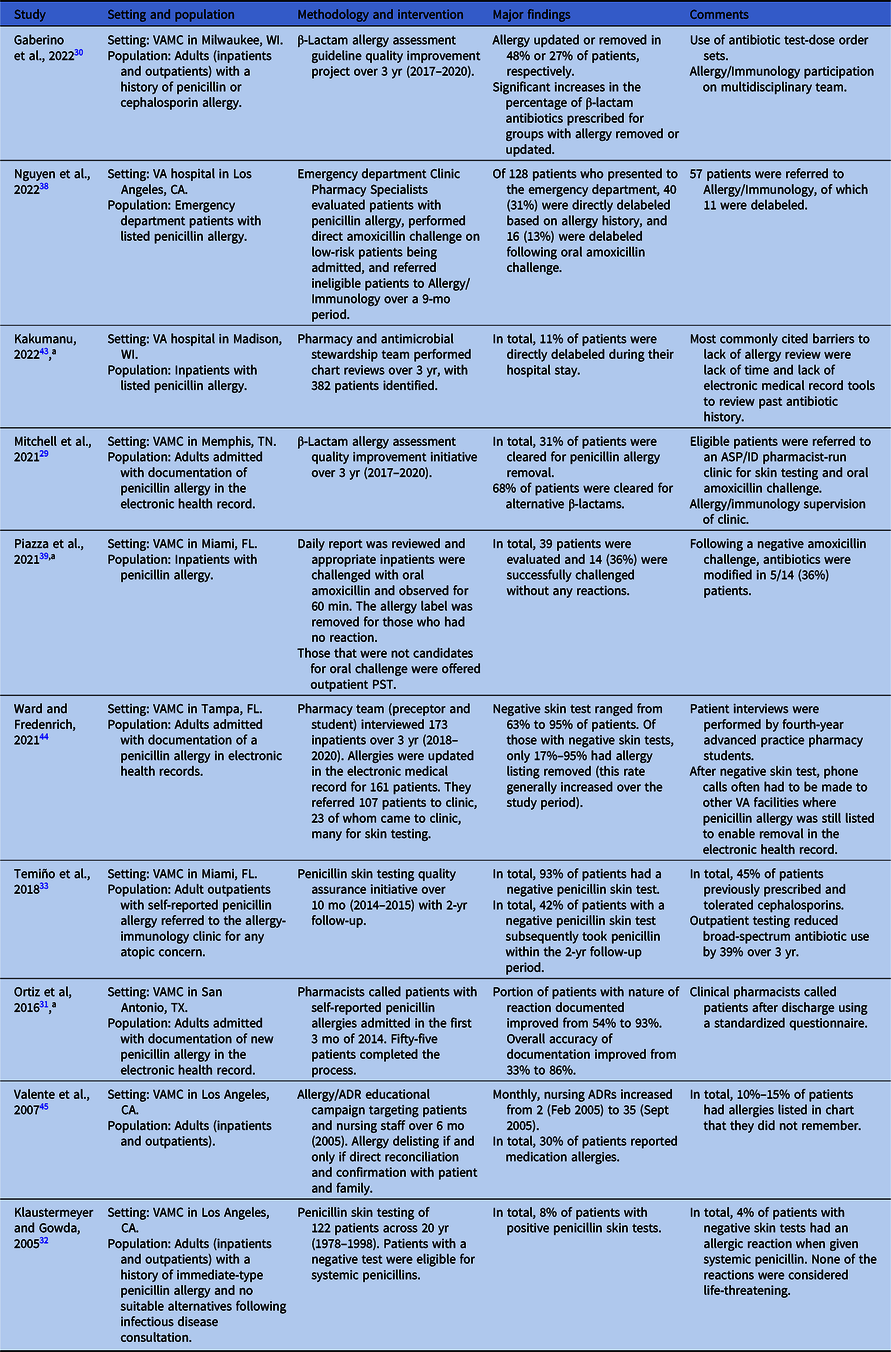

Table 2. Penicillin allergy evaluation within VHA

Note. ADR, adverse drug reaction; ASP/ID, antimicrobial stewardship program/infectious diseases; PST, penicillin skin testing; VA, Veterans Affairs; VAMC, VA Medical Center; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

a Abstract only available.

Prevalence and impact of unverified penicillin allergy labels within the VHA

The prevalence of allergies to penicillin-class antibiotics among inpatients at non-VHA facilities/systems ranges between 9% and 15%, Reference Sacco, Bates, Brigham, Imam and Burton2 and the literature suggests that this is similar within VHA facilities. McConeghy and colleagues evaluated allergy documentation for more than 10 million admissions to any VHA facility between 2000 and 2014, the largest VHA study to date. Reference McConeghy, Caffrey, Morrill, Trivedi and LaPlante15 They found allergy to one or more members of the penicillin-class of antibiotics to be the most frequently reported (13%), followed by opiates (9.1%), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (5.7%), and sulfonamides (5.1%). For patients who were determined to have an allergy to penicillin-class antibiotics, the most frequently documented reactions were rash (25.5%), hives/urticaria (13.8%), and swelling/edema (5.9%). Anaphylaxis was relatively rare, having been reported in just 3.1% of cases. Notably, documentation of the nature of reactions to penicillin-class antibiotics was missing in 43.3% of cases.

Within the VHA, available data on the impact of the penicillin allergy label are limited to single sites. Conway and colleagues performed a retrospective study at the VA Western New York Healthcare System, which included 403 patients admitted between January 2006 and December 2015 with a diagnosis of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, or sepsis. Reference Conway, Lin and Sellick16 The presence of a penicillin allergy label in the medical record was associated with a 50-min delay in the administration of the first dose of antibiotics in the emergency department and significantly higher rates of fluoroquinolone and carbapenem use as initial antibiotic therapy, as compared to those who did not have a penicillin allergy label. Patients with a penicillin allergy label were also significantly less likely than those without such a label to have their antibiotic regimen narrowed. The study authors did not identify any significant differences in total antibiotic duration, length of stay, or 30-d readmission rates between the groups.

Other VA single-site studies have also reported an association between β-lactam allergy (mainly to penicillin-class antibiotics) and suboptimal antibiotic choices both in the outpatient and inpatient settings. Reference Neu, Guidry, Gillion and Pattanaik17–Reference Mason, Kiel and White19 However, no consistent adverse signal on infection outcomes was reported in these studies, potentially attributable to the small sample sizes. A 60% average increased antibiotic cost was reported in veterans with penicillin allergy at one VA facility. Reference Biagtan, Babler, Kakumanu and Mathur20 In a multisite VA facility study, β-lactam allergy was also the most common reason for vancomycin perioperative prophylaxis in colorectal and vascular procedures. Reference Strymish, Oʼ Brien, Itani, Gupta and Branch-Elliman21

Importantly, and in contrast to non-VHA health system studies, Reference Kaminsky, Ghahramani, Hussein and Al-Shaikhly22–Reference Blumenthal, Shenoy and Huang24 we found no multisite VHA facility studies examining the impact of penicillin or β-lactam allergy labels on hospital length of stay, mortality, and adverse outcomes for specific infections (e.g., community-acquired pneumonia, surgical site infections, or Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia) in the veteran population (Table 1). This highlights an important gap in the literature and one which future studies should seek to address.

Advancing evaluation of penicillin allergies and delabeling within VHA

Access to penicillin allergy evaluations

The VHA Antimicrobial Stewardship Task Force conducted an agency-wide survey on antimicrobial stewardship programs in 2020 that revealed heterogeneity of access to penicillin allergy evaluation services. Among 138 respondent facilities, 28 (20%) reported having a formal process for evaluating patients with a penicillin allergy label, with only 17 of these 28 (61%) reporting ready access to penicillin skin testing (PST). Reference Mattison Brown, Roselle, Kelly and Echevarria25 However, 70 of the total 138 facilities (51%) reported the use of ad hoc processes for the evaluation of patients with documented allergies to penicillin-class antibiotics; no further information was reported on the mechanisms of these processes.

Nationally, there is a shortage of board-certified allergists—a well-recognized problem that is only expected to worsen in the coming years. Reference Malick and Meadows26 Although there are no published data that report on staffing levels in the VHA, it is known that many VHA facilities of varying sizes and complexity levels do not have allergy/immunology providers on staff. For those facilities without on-site access to allergy care, access to community (non-VHA) allergy specialists is available through the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Passed in 2018, the VA MISSION Act aimed to expand the services available to veterans by allowing them access to services in the community, primarily when VHA is unable to provide the service directly because of excessive distance from or an extended wait time at a VHA facility. 27 Although veterans with penicillin allergy labels enrolled at the majority of VHA facilities would be eligible for this expanded access to care, the successful utilization of this alternative pathway is contingent upon a number of factors, which include the local availability of contracted allergy providers, awareness on the part of the primary care provider to initiate a referral for penicillin allergy evaluation, the ability of the veteran to travel to the contracted allergy provider, reliable propagation of the results of any allergy evaluation back to VHA, and the subsequent modification of the allergy listing in the veteran’s electronic health record. Based on our review of penicillin allergy evaluation within the VHA (Table 2), we were unable to identify a single study examining the impact of the VA MISSION Act or use of community allergy providers for penicillin allergy evaluations.

Direct delabeling from chart review

Since the 1970s, the VHA has been a pioneer of electronic health records, with all facilities having implemented the VHA’s Computerized Patient Record System by 1999. 28 The presence of a standardized and interconnected record allows providers to view the details of patient records, including medication and allergy histories, from any other VHA facility where a patient received care. This record-keeping goes back decades, which is a considerable advantage when evaluating a patient for direct delabeling based on chart review.

At the Memphis VA Medical Center, Mitchell and colleagues implemented a program in which clinical pharmacy specialists evaluated and interviewed patients admitted with β-lactam allergies and then documented their assessments and recommendations: clearance for alternative β-lactams, avoidance of all β-lactams, direct removal of the allergy label, or (beginning January 2019) referral to a pharmacist-led penicillin allergy clinic for PST. Reference Mitchell, Ness and Bennett29 Of 278 patients screened between November 2017 and February 2020, 62 had their allergy labels removed following this program’s evaluation with an additional 180 eligible for alternative beta-lactams following this program’s evaluation.

Gaberino and colleagues at the VA Medical Center in Milwaukee instituted a multidisciplinary (emergency medicine, allergy, internal medicine, and infectious diseases) guideline in November 2017 to guide antibiotic management and β-lactam allergy relabeling for patients with documented β-lactam allergies. Reference Gaberino, Chiu and Mahatme30 Like Mitchell et al, outcomes included complete allergy label removal, update of the allergy record to support use of other β-lactams, and no change to the label; notably, there was no option for referral to a penicillin allergy clinic. Between November 2017 and February 2020, they identified 79 patients with a β-lactam allergy label (90% penicillins and 10% cephalosporins). Complete removal of the allergy label was feasible for 27% of these patients, resulting in a significant increase in the use of β-lactam antibiotics (44%–77%; P < .001).

Evaluation and clarification of penicillin allergies have also occurred asynchronously without the need for inpatient admission or an outpatient clinic. Ortiz and colleagues led an initiative at the South Texas VA Health Care System in San Antonio that utilized a team of pharmacists to improve the accuracy of recently documented penicillin allergies. Reference Ortiz, Buchanan, Song, Gonzalez and Echevarria31 They identified 229 patients with new penicillin allergies documented between October 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015, 55 (24%) of which were contacted to complete a short questionnaire regarding their allergy history. This process resulted in the documentation of the nature of the reaction in 93% of cases (compared to 54% in a preintervention cohort), and documentation of other key elements (date and timing of the reaction and history of antibiotic use since the reaction) improved to 66% or better from a preintervention rate of less than 2%. Overall, accuracy improved to 86% postintervention compared with 33% prior to the intervention. Of note, this initiative did not include the removal of penicillin allergy labels, and the lack of long-term follow-up on subsequent antibiotic use limits the understanding of the overall impact of the program.

Penicillin skin testing and direct oral amoxicillin challenge

For decades, referral to allergy clinics for PST (with or without subsequent oral amoxicillin challenge) has been the standard approach for evaluating penicillin allergy both outside and within the VHA. In 2005, Klaustermeyer and Gowda reported on the experience of the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center, where PST was performed under a research protocol from September 1978 through May 1998. Reference Klaustermeyer and Gowda32 Patients were identified from both inpatient and outpatient services, and all of those included had a reported history of reaction to a penicillin-class antibiotic within 48 h of exposure. PST was only performed in consultation with infectious diseases and in cases where no suitable alternative agents were available for treatment. Over the study period, 122 patients underwent PST, of which 110 (90.2%) had their allergy labels removed.

More recently, Temiño and colleagues at the Miami VA Medical Center reported on a successful pilot program to offer routine PST to all patients seen in an outpatient allergy clinic for any reason. Reference Temiño, Gauthier and Lichtenberger33 Between May 2014 and March 2015, 40 patients underwent PST and 1 underwent oral amoxicillin challenge without a preceding PST. Of the 40 patients who underwent PST, 38 (93%) had negative reactions and proceeded to oral challenge, only one of whom had a reaction of any sort (fixed drug eruption that developed approximately 10 h following negative PST). Through March 2017, 16 of the 38 patients who had a negative PST received 23 unique courses of penicillin-class antibiotics, a majority of which (57%) were taken by the 10 patients originally referred by the infectious diseases or spinal cord injury services. This program highlights the potential value of targeting efforts to select populations within the VHA who are most likely to need future antibiotic treatments.

In addition to the direct removal of allergy labels following careful evaluation as discussed previously, Mitchell and colleagues also referred select patients to a pharmacist-driven clinic for PST followed by oral amoxicillin challenge. Reference Mitchell, Ness and Bennett29 Of the 32 patients referred, 24 were able to have their allergy labels removed through direct testing. Of the eight patients who could not be delabeled, PST confirmed the allergy in five (62.5%) and was inconclusive in three (37.5%); clearance for alternative β-lactam agents was given and documented in the patients’ charts. At the time of this publication, the authors reported that 147 (80%) of the 184 patients evaluated at the Memphis VA Medical Center who were eligible to be seen in the penicillin allergy clinic were awaiting scheduling for possible PST, highlighting how the use of a clinic-based penicillin evaluation service could create a potential bottleneck.

This model has since been adopted by the VHA’s Innovations Ecosystem (a program to drive forward innovations within the VHA) 34 and has recently resulted in the launch of a voluntary program termed ABLE—Allergy to Beta-Lactam Evaluation—to assist pharmacists in the evaluation and clarification of penicillin allergies. 35 The program benefits from multidisciplinary stakeholder collaboration, leveraging the interconnected nature of the VHA computer systems and standardized electronic health records to facilitate rapid implementation of predeveloped templates, protocols, and documentation tools, with minimal required modifications. However, limitations to this strategy include reliance upon a voluntary physician champion (usually one specializing in allergy/immunology) and a dedicated clinical pharmacist as well as the need for clinic space and support staff if performing outpatient evaluations. These are limited resources at many VHA facilities, and securing them to implement and support a new, nonurgent service among a field of other competing services and programs that serve the needs of veterans can be a challenge.

Direct oral amoxicillin challenge (without preceding PST) has emerged as a safe and effective means of delabelling patients with low-risk allergy histories and is supported by a recent randomized controlled trial. Reference Copaescu, Vogrin and James36 Under this paradigm, patients who are deemed to have low-risk penicillin allergy histories are given a one-time dose of amoxicillin 250–500 mg orally and then observed for 30–60 min; patients who do not have a reaction may then have their penicillin allergy label removed from the chart. A major advantage to this approach is the lower barrier to implementation—in terms of the decreased need for special training in administering PST agents and interpreting the results, the use of a medication product already stocked at most facilities, and a decrease in the time required for each challenge—as compared to PST. Although we are aware of several efforts to implement direct oral amoxicillin challenges within different VHA facilities, including the recently launched ABLE initiative, there are no published, peer-reviewed, VHA system-wide data on the implementation and effectiveness of this approach. Given the endorsement of this approach in the 2022 practice parameter update from AAAAI and ACAAI and the ease of safely implementing this strategy without the need for allergy/immunology specialist oversight, we strongly support this practice and efforts to implement it within the VHA. A sizable proportion of veterans would be eligible for this evaluation, as supported by the literature.

However, penicillin allergy evaluation and direct oral amoxicillin challenge need not be limited to dedicated services, and several efforts have been made to incorporate these activities into pre-existing clinics/services. Using national data from VHA’s Corporate Data Warehouse, Vivo and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of patients with outpatient dental clinic visits at any VHA between 2015 and 2018. Reference Vivo, Durkin and Kale37 They identified 26,236 patients who had a dental visit with an associated antibiotic prescription within 7 d of the visit and who had prior documentation of a non-anaphylactic allergy to penicillin; identified prescriptions were predominantly (98%) for non-cephalosporin antibiotics. After analyzing a geographically stratified random sampling of 100 of those patients who did not receive a cephalosporin antibiotic, the authors determined that over a quarter of these patients would have been eligible for direct oral amoxicillin challenge. We have identified limited single-VA facility reports of the use of direct oral amoxicillin challenge as a means of removing penicillin allergies: one report by Nguyen and colleagues at the VA Greater Los Angeles Health Care System focused on patients in the emergency department Reference Nguyen, Pham, Calub, Yusin and Graber38 and one by Piazza and colleagues at the Miami VA Medical Center detailing their experiences in the inpatient setting. Reference Piazza, Lichtenberger, Bjork, Lazo-Vasquez, Hoang and Temino39 While the available data indicate that these programs appear to be safe, the overall numbers of patients are small, and more data are needed to truly understand the potential impact and feasibility of such a strategy.

Although the above experiences highlight the advantages of using direct oral amoxicillin challenges to delabel patients with low-risk allergy histories, we have found that implementation of this approach also has some challenges. First, a direct challenge requires patient monitoring for 30–60 min after the challenge dose is administered, which can be hindered by staff availability. Additionally, patient, family member, and healthcare worker beliefs regarding the safety of penicillin allergy removal and adjustment of the medical record present barriers, as reported in a recent VHA study by Gillespie and colleagues. Reference Gillespie, Sitter and McConeghy40 These challenges highlight why interdisciplinary collaboration, targeted education, and communication are key to ameliorating concerns regarding patient safety and preventing increased workload burdens among frontline staff.

Discussion

Although much is known about the prevalence of penicillin allergy labels within the VHA, there is a relative paucity of data on the impact of such labels on clinical outcomes for veterans admitted to VHA facilities. Implementation studies within the VHA on either PST or direct amoxicillin challenges have had direct support from internal allergy/immunology providers, which calls into question the scalability of facilities lacking such support. The recent development of a centralized hub of resources to assist pharmacists in penicillin allergy evaluation and removal within the VHA is encouraging, but further prospective studies will be needed to assess its adoption and impact on patient care including cost, length of stay, delays in initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment, and relabeling. Future studies should also give consideration to contextual barriers, the dependability of the VA MISSION Act to utilize non-VHA-allergy/immunology providers, the use of telemedicine in rural VHA facilities, and the unique challenges presented by vulnerable veteran populations with penicillin allergies, including those who have communication barriers, substance use disorder, or are without housing or reliable transportation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2023.448.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Hannappel and the VA North Texas Health Care System Library for their assistance in the literature search. We thank Allison Herrera and Roger Bedimo for their thoughtful input and comments regarding this manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Academy of Medicine or the National Academy of Sciences.

Author contribution

MAK, DFS, and RJA were primarily responsible for drafting the manuscript. DNM, DFS, LY, and JMG were responsible for development of the included tables and figures. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript text. Overall work was supervised by RJA.

Financial support

This publication is supported by the National Academy of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences under award number 20000013468.

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.