Introduction

Whilst it is undeniable that the United Kingdom's (UK) population is ageing, there has been some disagreement as to whether improvements in longevity have been matched with improvements in, what the European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit terms, ‘healthy life years’. Kingston et al. (Reference Kingston, Wohland, Wittenberg, Robinson, Brayne, Matthews and Jagger2017) note that a transformation in life expectancy has brought with it two somewhat disparate shifts, whereby a greater number of people are remaining independent for longer but, also, a greater number of people are experiencing care needs and for a longer period of time. Concerns have been expressed about the decline in capability and independence brought on by an expansion of the older population (Marengoni et al., Reference Marengoni, Angleman, Melis, Mangialasche, Karp, Garmen, Meinow and Fratiglioni2011) which is, in turn, resulting in increased demand for (already under-resourced) care and support services. The expansion of the older population has led to an increase in the number of older people with diverse housing, care and support needs. Indeed, debates about the provision and affordability of both housing and care for those over the age of 65 have become key features of social policy internationally (Pynoos, Reference Pynoos2018).

It is within this context that, in the UK and elsewhere, there has been heightened interest in housing with care models amongst social care professionals, policy makers and older people themselves (Tinker, Reference Tinker2002; Copeman and Porteus, Reference Copeman and Porteus2017). In particular, this interest has centred on the intended role of housing with care in reducing the need for residential care as well as in facilitating the maintenance of independence (Croucher et al., Reference Croucher, Hicks and Jackson2006). In terms of provision, such interest has resulted in an increase in the number of housing with care schemes which ‘conform neither to pure sheltered housing nor pure residential care’ (Oldman, cited in Croucher et al., Reference Croucher, Hicks and Jackson2006).

Extra-care housing (ECH) is a form of housing with care provision for older people which has gradually grown in popularity since the early 1990s, with approximately 1,600 schemes available by 2016 (LaingBuisson, 2016). Though there is some disagreement about how ECH is best defined, researchers tend to agree that three key factors make it is a distinct alternative to other forms of housing and care provision (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Atkinson, Darton, Cameron, Netten, Smith and Porteus2017). They are: its focus on ‘supporting independent living in self-contained accommodation for rent, shared ownership or sale’ (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Atkinson, Darton, Cameron, Netten, Smith and Porteus2017: 20); its emphasis on the provision of communal facilities, such as lounges, restaurants, launderettes, gardens and/or social activities; and its provision of 24-hour care on-site (Evans and Vallelly, Reference Evans and Vallelly2007). A key feature of this care is that it should be responsive and flexible, adapting to the changing needs of older people on a permanent or temporary basis. The provision of care in ECH therefore constitutes an ‘extra’ service that residents can draw upon as and when it is required. There has been growing interest in ECH across the United States of America, Australasia and Europe, where it has been variously named ‘assisted living’, ‘senior housing’, ‘service housing’ or otherwise (Howe et al., Reference Howe, Jones and Tilse2013; Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Evans, Darton, Cameron, Porteus and Smith2014).

In this paper, we explore the perspectives of older people living in four different ECH schemes in England, focusing on how ageing is experienced, negotiated and managed by these individuals within the context of the environments where they live.

The third and fourth ages

It was the expansion of the population aged over 65 that led Laslett (Reference Laslett1987) to outline his theory of the third age, which endorsed later life as a time of agentic self-fulfilment, consumption and active engagement. Although Laslett's work is contested and not universally applicable, it is useful for considering how older people (as third agers, at least) are able to maintain their functioning and dignity. Third agers, however, were distinguished from fourth agers, who were regarded as having little agency, dignity or independence (Baltes and Smith, Reference Baltes and Smith2003; Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010). In light of the suggestion by Kingston et al. (Reference Kingston, Wohland, Wittenberg, Robinson, Brayne, Matthews and Jagger2017) that later life is now made up of a longer period of independence and a longer period spent with care needs, we might conclude that there has been an elongation of both the third age (young old) and the fourth age (oldest old) (Baltes and Smith, Reference Baltes and Smith2003; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Doblhammer, Rau and Vaupel2009).

Though there is some agreement that one's movement from the third age into the fourth age does not directly relate to one's chronological age (Laslett, Reference Laslett1987, Reference Laslett1991; Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010), there is disagreement about how each age (and the fourth age, in particular) should be conceptualised, how each age relates to the other, and how clear-cut and impermeable the boundary is between the third age and fourth age.

Whilst the third age has been trumpeted as a leisurely, active and autonomous period of life, less academic attention has been given to understanding how dependencies are experienced in the so-called fourth age (Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014). Attention has been placed on the care of older people, but this has mostly (and disproportionately) been from the perspective of service providers and tends to focus on the management of decline rather than on understanding an individual's experience of dependencies. In response to the lack of conceptual clarity concerning the fourth age, there has been some recent focus on pinpointing when the fourth age begins and on identifying its key characteristics. In this paper, we use the concepts of the third and fourth age to explore findings from our study, rather than treating each as a clear-cut category into which older people themselves can be neatly classified.

The boundary between the third and fourth age

Gilleard and Higgs’ (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010) assumption is that the institutionalisation of older, infirm persons into social care environments functions to propel those persons into the fourth age. For Gilleard and Higgs, it is when an individual is deemed by professionals (care workers, medical practitioners, care assessors) to have lost their ability for self-care that they cross the ‘event horizon’ into the fourth age, where ‘choice, autonomy, self-expression, and pleasure collapse into silent negativity’ (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 126). Other researchers have drawn attention to the difficulty of conceptualising and identifying the characteristic features of the fourth age (Twigg, Reference Twigg2006; Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014; Lloyd, Reference Lloyd, Twigg and Martin2015). Such difficulties arise, not least, because sanguine narratives of the third age often rely upon a rejection of the negative discourses associated with more traditional accounts of ageing: dependency, deterioration and disengagement. In attempting to rescue the fourth age from gloomy depictions of a period lived without agency, choice or social connections, researchers have examined how will, self-determination and control may be exercised by individuals despite bodily decline or dependency (Heikkinen, Reference Heikkinen2000).

Lloyd et al. (Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014) use the term ‘perseverance’ to describe how, whilst the older people in their study were aware that decline was inevitable, they had not given up on the exercise of will or self-determination. This was not a resistance to and denial of the fourth age like that described by Gilleard and Higgs, but neither was it an acquiescence or acceptance of decline. For the older people in the study by Lloyd et al. (Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014), experiencing bodily decline, poor mobility and ill-health did not prevent them from being engaged in decisions about their care as well as in relationships with others which were not completely dependent.

The boundary between the third age and the fourth age remains a domain of ‘unresolved tension’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 121) in academic research (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd, Twigg and Martin2015). The accounts of the participants in the study by Lloyd et al. (Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014) raise further questions about how the third and fourth ages, and particularly the boundary between them, is best conceptualised. We might suggest, for example, that entry into the fourth age is marked not by a ‘cliff edge’ but by a complex period of transition or liminality. Recovery and remission from illness during later life, for example, undermines the assumption that the fourth age presents a ‘void’ from which older people cannot return (Grenier, Reference Grenier2012; Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014).

Equally, we might argue that the fourth age is a less gloomy place than many have envisioned. Since transition across this boundary involves a change in the status of the individual, we would expect it to be marked by a period of liminality; that is, a period in which the individual is neither of the third age nor of the fourth age but, instead, is between the two. Researchers have explored several ways in which people may experience liminality as they age. Here, focus has been placed on older people's experiences of the unsettled status and identity resulting from transitions into residential or nursing homes (Diamond, Reference Diamond1992; Frank, Reference Frank2002) or into hospitals or hospices (Froggatt, Reference Froggatt1997; Hirst, Reference Hirst2002; McKechnie et al., Reference McKechnie, Jaye and MacLeod2011). Indeed, care environments may increase vulnerability and other features associated with the fourth age rather than functioning as a response to them (Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Lloyd and Phillipson2017). More recently, it has been recognised that periods of liminality associated with transition between the third and fourth age might follow the uptake of care at home (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Hale and Gauld2012) or the onset of failing health or frailty (Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Meyer, Flatley, Holman and Lowton2012; Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014), regardless of whether one moves into a formal care environment.

West et al. (Reference West, Shaw, Hagger and Holland2017) explore the sense of persistent liminality experienced by older people living in ECH. Unlike the institutional care environments alluded to by Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010), ECH schemes tend to be marketed as third age, rather than fourth age, spaces. A core emphasis of ECH, however, is the ability for residents to age in place and, in some instances, to treat ECH as a ‘home for life’. These somewhat competing discourses make clear how ECH residents might find themselves in a liminal state; neither securely of the third age nor of the fourth age, neither independent nor dependent, and both living in a care environment and in their own home. ECH, in this sense, presents an interesting case for further analysis into how older people might manage their changing care needs as they age.

ECH: housing for the third age?

Since resistance towards the social categorisation of old age has been considered a key feature of the third age habitus (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010), it is perhaps unsurprising that such resistance is often cultivated and sustained by marketing for social care services. This is more the case for ECH, which has been hailed as an alternative to, or even as a replacement for, more traditional forms of social care provision in that it promotes independence and choice (Department of Health, 2004).

Others, however, have argued that, whilst ECH offers a viable alternative to residential care for some older people, it should not be viewed as negating the need for residential care environments (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Croucher, Fry and Jasinska2013). The Personal Social Services Research Unit's evaluation of 19 ECH schemes, for example, found that ECH residents were less dependent and less physically and cognitively impaired than care home residents (Darton et al., Reference Darton, Bäumker, Callaghan, Holder, Netten and Towers2012). It has been suggested elsewhere that ECH cannot easily support the same population as that served by care homes (Croucher et al., Reference Croucher, Hicks, Bevan and Sanderson2007).

In the late 1990s, Robson et al. (Reference Robson, Nicholson and Barker1997) drew this distinction between ECH and care homes when they titled their design guide for extra care Homes for the Third Age. There is, however, growing evidence that the population served by ECH is moving away from this third age cohort. Skills for Care's (2017) recent research, for example, indicates that local authorities’ funding provision for ECH residents is increasingly limited to individuals who have high care needs. It is not clear whether the same shift in population can be observed in those ECH schemes that cater predominantly for people who fund their own care. However, concerns have been expressed that a shift towards resident populations with higher care needs overall may discourage more active prospective residents from moving into ECH schemes (Croucher and Bevan, Reference Croucher and Bevan2010; Darton et al., Reference Darton, Bäumker, Callaghan, Holder, Netten and Towers2012). Alongside a shift in the demographic of older people entering ECH – who have higher care needs than those who moved into ECH in the past – existing residents are ageing in place. This has resulted both in a reduction of ECH residents’ ‘mix’ of abilities and an expansion of the number of ECH residents who are undergoing a period of liminality between the third and fourth ages (Skills for Care, 2017; West et al., Reference West, Shaw, Hagger and Holland2017).

Indeed, the research of West et al. (Reference West, Shaw, Hagger and Holland2017), alongside that of others (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Bartlam, Sim and Biggs2007; Croucher et al., Reference Croucher, Hicks and Jackson2006), drew attention to how the dialectic between the third and fourth age can be alleviated or amplified by the discursive practices of ECH schemes. In this paper, we extend the analysis of West et al. (Reference West, Shaw, Hagger and Holland2017) by focusing on how operational practices within four ECH schemes shaped residents’ management of their own liminality at the boundary between the third and fourth ages. Our focus here is not on how liminality is experienced amongst ECH residents as a group, but on how individual residents were able to exert agency and control (or not) as they aged within the context of ECH. Indeed, the focus of this paper is not on establishing how best to categorise the experiences of older people who are ageing in ECH (e.g. of the third age or the fourth age) but, instead, to consider how these individuals might negotiate and experience their ageing in the context of ECH. For this reason, drawing upon the longitudinal data gathered in the study, we emphasise the lived experiences of ageing persons in ECH and, in particular, the impact that normal routines and everyday practices within ECH schemes – admissions criteria for funded residents, philosophy, facilities, design, sense of community, organisation of care – have upon these residents’ ability to express agency or exert control over their changing care needs.

The ECHO project: an empirical study

The longitudinal data upon which this paper draws are from a recently completed National Institute for Health Research, School for Social Care Research-funded study titled ‘The Provision of Social Care in Extra Care Housing’. The study examined the experiences of 51 older people living across four ECH schemes, as well as examining the perspectives of 20 care workers and seven managers who worked in these ECH schemes, and three local housing and care commissioners. The overarching aim of the study was to explore how care is negotiated and delivered within ECH settings and, in particular, how changes in residents’ care needs were responded to both individually and institutionally. The research focused on four key research questions:

(1) How do residents in ECH schemes make decisions about the changing nature of their care needs and how do they negotiate these with care providers?

(2) How do providers of care negotiate changes to the provision of care, both at an organisational and individual level?

(3) How do front-line staff mediate, and respond to, the changing needs of residents and the constraints faced by managers of extra-care schemes?

(4) How do commissioners of extra-care housing and social care negotiate changes in care with providers?

In this paper, we focus on answering the first research question by drawing upon data gathered in longitudinal interviews with residents. We consider how older people living in ECH schemes make decisions about their changing care needs, establishing how they manage and negotiate the liminal state of being betwixt and between the third age and the fourth age. The project was a longitudinal study, an approach that is used increasingly in social policy research as it offers the opportunity to explore processes of change over time (Corden and Millar, Reference Corden and Millar2007). A qualitative longitudinal approach enabled us to consider how residents of ECH negotiated and managed the uncertainties and ambiguities brought on by changes in their care needs. Ethical approval was obtained from the National Social Care Research Ethics Committee (reference number 15/IEC08/0047).

Methods

The study involved visiting four ECH schemes, which were located in two distinct geographical areas, four times over the course of 20 months. Methods used included: semi-structured interviews (with residents, care staff and managers at each scheme, as well as commissioners of housing and care); analysis of documents; and unstructured observations. Since the focus of this paper is on how residents managed their changing care needs within the context of ECH, we draw upon the in-depth, longitudinal interviews which were carried out with ECH residents on four occasions over the 20 months during which we visited the four schemes. A longitudinal approach was chosen due to our interest in the changes experienced by residents over time, and particularly on individual and organisational responses to these changes. Adopting a longitudinal approach also provided us with an opportunity to establish relationships with the resident interviewees which, in turn, gave us a deeper understanding of the opportunities and challenges which they faced.

Each phase of interviews undertaken with residents was distinct. The first interview covered biographical details including age, relationship status and the length of time that they had lived in ECH. Introductory interviews also explored residents’ reasons for moving in, participation in social activities, social contact, health status, whether they received direct care, changes in care over time and experiences of care. Subsequent interviews (rounds 2–4) explored whether there had been any changes in the resident's care, in their experiences of care or in their health. In addition, subsequent interview rounds included a focus on different themes such as friendships and hobbies, both before and after moving into ECH, and loneliness and isolation. These additional themes emerged inductively during the initial analysis of data gathered in previous rounds of interviews and aided us in understanding the impact of changes in care needs on the lives of individual residents.

The schemes

We recruited four ECH schemes as sites for data collection. One of these provided specialist support to people with dementia. The sites were based in two areas. Sites A and B were located in Area 1 and Sites C (the specialist dementia scheme) and D in Area 2. Area 1 was a unitary authority, experiencing pressure on land with plans for large-scale investment in ECH. Area 2 was a county council, two-tier authority, which struggled to fill those places in the schemes that were designated for local authority-supported people.

All four schemes conformed to general definitions of ECH. They provided self-contained accommodation (in the form of apartments) to adults aged over 55, had communal spaces such as lounges and restaurants, and had care and support available on-site. There were, however, many differences between the four schemes in terms of resident type (care needs; funding arrangements), activities programmes, available facilities, and layout and material environment. Some of these differences between the schemes are presented in Table 1. The impact of such differences upon residents’ abilities to manage their changing care needs is explored in more detail later in the paper.

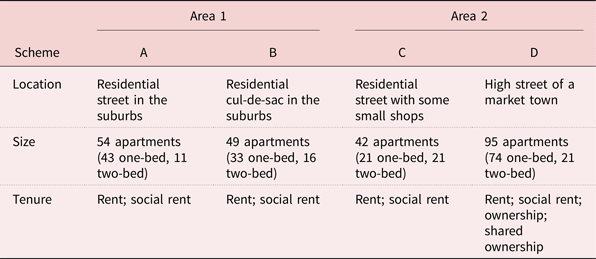

Table 1. Research sites

The process of assessing and placing prospective ECH residents varied between Area 1 and Area 2. In both areas, access to ECH for publicly funded residents was via the local authority's nominations process and residents were assessed either prior to entering ECH or when their care needs were thought to have changed. In Area 1, however, the authority's allocation policy was revised during the study to focus on the presence of care needs, as opposed to housing needs. For self-funded residents in both areas, the admissions process usually entailed older people and/or their families visiting the scheme before applying to move in. Differences between the four schemes were reflected in the sample of participants interviewed at each.

The participants

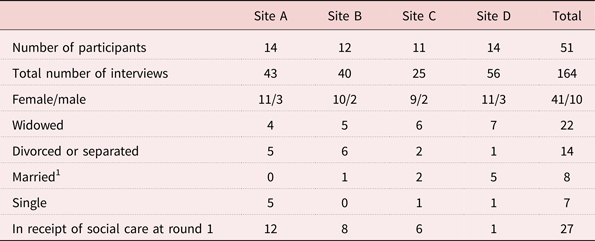

Our intention was to recruit ten residents at each scheme and interview them four times over 20 months so that we could understand how care needs change and how they are responded to by older people, care workers and managers. With the potential for high attrition rates in mind, we decided to recruit between 12 and 15 residents at each site during our first round of interviews. A total of 51 residents took part in the study, 12 of whom were recruited during our second round of interviews. Upon the completion of fieldwork, ten participants had withdrawn from the study (three had lost capacity, two chose to withdraw, two had moved to nursing homes and three had died). In total, we undertook 164 interviews across the four rounds. Table 2 provides further detail regarding the nature of our sample at each site. Several residents whom we spoke to were not aware of how their housing and/or care was paid for – that is, whether they were self-funded or local authority-funded – and, for this reason, information pertaining to funding sources is not included here.

Table 2. Participant details (extra-care housing residents)

Note: 1. All participants who were married lived with their spouses.

Although we wanted to include the experiences of people with dementia living in ECH, we took the decision to include only people who had capacity to consent. To enable us to include people with dementia who had capacity to consent, we used a process consent method (Dewing, Reference Dewing2007) to check ongoing capacity on each occasion that we interviewed residents. Written informed consent to be interviewed was obtained from participants at each stage of the research and all participants had the capacity to consent.

Analysis

All interviews with residents were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Initially, a sample of eight transcripts from the first round of resident interviews were read and independently coded by three members of the research team. Discussion of these transcripts led to the development of an initial coding frame which was used to code the first wave of resident interviews thematically using NVivo software. The coding frame was supplemented with additional themes as they emerged, both during coding and following each subsequent round of interviews. In this paper, we focus on themes related to residents’ changing care needs, transitions, ageing, health, and choice, autonomy and independence.

Findings

The findings discussed below are drawn from data obtained through interviews with residents in the four ECH schemes that participated in the ECHO project. Our focus here is on answering the first of the ECHO project's four research questions. That is, how do residents in ECH schemes make decisions about the changing nature of their care needs and how do they negotiate these with care providers? We outline four key ways in which residents living in the four schemes endeavoured to plan for, eschew or manage their changing care needs. Such endeavours were not always successful. For some residents, the onset of illness, reduced mobility or disability drove them, albeit unwillingly, into a state of dependence and disengagement which we might associate with the fourth age. For others, however, it was the context of ECH itself which impeded their attempts to exert choice and control over their changing care needs. In what follows, we discuss our findings under four sub-headings, broadly reflecting distinct yet interrelated topics: (a) preparing for the future; (b) avoiding decline; (c) resisting dependency; and (d) managing care provision. Data are presented using pseudonyms.

Preparing for the future

A key focus of our initial interviews with residents was their transition into ECH and, in many cases, residents spoke at length about their previous circumstances, their reasons for moving and who had been involved in the decision.

Pre-emptive

For some residents, moving into ECH was framed as a form of future-proofing. This was particularly the case at Site D, where the majority of residents whom we spoke to did not have a current need for care. For example, when asked about her main reason for moving into ECH, Cynthia, from Site D, said:

Well I knew that … I haven't any near family. Rather short on family actually, I have a brother but we were orphaned quite young and grew up in different families … So I realised if I was ill or anything I'd be in trouble. And I mean, for years told people you can't rely on all your neighbours, you'll wear them out, you know?

Marjorie, who lived at Site D with her husband, described their decision to move into ECH as not only preparatory but also timely:

The reason we moved we were in a bungalow in [place], which … was large, the garden was large, transport was, public transport was getting worse and my husband no longer drives, therefore we felt it was about time we moved and care needs could be coming up as they have actually and it was the best thing we did moving here.

It is perhaps unsurprising that some older people whom we spoke to described their decision to move into ECH as one based on an anticipated future need for care. In their analysis of data gathered in 31 ECH schemes, Kneale and Smith (Reference Kneale and Smith2013: 282) similarly concluded that the decision to enter ECH is, for many, ‘likely to be a pre-emptive move in anticipation of deterioration in health, a lifestyle choice, or, in the case of couples, may reflect the health of the partner’. This is reaffirmed in the findings of other studies of the decision-making and characteristics of those moving into ECH (Bäumker et al., Reference Bäumker, Callaghan, Darton, Holder, Netten and Towers2012; Darton et al., Reference Darton, Bäumker, Callaghan, Holder, Netten and Towers2012).

Such a pre-emptive move undoubtedly requires that the older person foresees a future change in their care needs. Nonetheless, much like participants in the study by Lloyd et al. (Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014), this consciousness that decline was inevitable did not cause residents in our study to give up on the exercise of self-determination. Instead, it was an awareness of one's ageing that allowed participants to exert control over the provision of their future care. This awareness spurred participants to make preparations which would allow them to avoid being ‘in trouble’ (Cynthia, Site D) should they become unwell and, particularly in the case of Site D, to avoid long waiting lists for an ECH place if/when a need for care did arise.

Proactive

For other residents, whilst the move into ECH followed rather than preceded a change in care needs, this move was the result of a proactive decision made by the resident. At Site C, the specialist dementia site, for example, Patricia spoke about how her decision to move into ECH came as a surprise to her family, with whom she was living at the time:

The reason [for moving] really was I was lonely, and also I knew that my legs were getting worse and not being able to get out and I just felt that it was the time … I think they [my family] were a bit surprised at first. Like me. I was a bit surprised that it was happening so soon. I said ‘I'm lonely, I'm very lonely’, I said ‘I can't stop here’. So that was that really. I'd made the decision.

Older residents of ECH envisioning their own future needs for care might be read as evidence of their fear of (or concern about) transitioning into the fourth age. What is distinct about these accounts, however, is that they frame the decision to move into ECH not as an attempt to ‘steer clear of’ or ‘put off’ the fourth age ‘for as long as possible’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 127; Laslett, Reference Laslett1987: 154), but as a rational, preparatory decision to secure quality care provision and quality of life in the fourth age. This aligns with previous accounts of the move into ECH as being something that is more often planned in anticipation of needs rather than a response to a crisis or immediate need (Bäumker et al., Reference Bäumker, Callaghan, Darton, Holder, Netten and Towers2012; Darton et al., Reference Darton, Bäumker, Callaghan, Holder, Netten and Towers2012).

Whilst the marketing of some ECH schemes rests upon the social imaginary of the third age, it was the provision of care within ECH – just as much as the lifestyle options which it presented – which encouraged these older people to make the move. There may be an argument here that residents are conforming to prescribed roles, that is, that they would be regarded as self-determining and assuming the position of expectations of moving into the fourth age. However, in our study, we argue that the residents’ claims, instead, depart from conceptualisations of the transition into a care environment as an ‘event horizon’ which is regulated by professionals and beyond which lies the social death of the subject (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010).

Reactive

For other residents whom we spoke to, the decision to move into ECH was more reactive and, in some cases, residents did not feel that they had been involved in the decision-making process. We were unable to collect data regarding how every resident's care was funded because many were either not aware of or could not remember this information. It did appear, however, that publicly funded, as opposed to self-funded, residents were more likely to feel that they had been left out of decisions about moving into ECH. The accounts of these residents often referred to the role of family members or professionals in arranging their transition into ECH. At Site A, for example, Phillipa said:

Well there used to be a woman here that used to be the manageress, and she came to my bungalow where I lived, and the doctor said I was falling down a lot, so she came, and that's how I came in here. She told me about this place, and she brought me in, and I've been here ever since.

For other residents, it was a housing need, rather than a care need, that had spurred the move into ECH. Residents referred to how their local council had ‘run out of room’ to accommodate them elsewhere (Sally, Site B) or spoke about how their move into ECH had been arranged because of previous landlords wanting to ‘get rid’ of them (Harry, Site B), due to problems with previous neighbours, or due to unsuitable or inaccessible accommodation. Interestingly, this included residents in Area 1 who had moved into ECH after a change in the allocation policy, which required that it was care needs, rather than housing needs, that were the focus of assessments and placement decisions.

Those residents who described their move into ECH as a reactive one (where decisions were often made by others) were more typically of the fourth age in Gilleard and Higgs’ terms, since they did not control the move. Many of these residents relied on local authority funding for their housing and/or care. Since funding is dependent on both financial eligibility and eligibility in terms of need, the move of funded residents into ECH is almost always a reactive, rather than pre-emptive, one. This explains differences in our sample between sites, where the site which had the lowest proportion of funded residents and which offered accommodation for purchase – Site D – was also the site where our sample population had the fewest care needs.

Avoiding decline

Residents across all four sites spoke about their attempts to delay their need for care or, in some cases, to avoid increasing the amount of care which they received. These attempts involved a variety of strategies, but key amongst these was keeping busy, both physically and mentally.

Keeping busy

Keeping busy was viewed by many residents as a way to prevent physical or mental decline; as one resident, Esther, at Site A said, ‘if you don't use it, you lose it (laughs)’. For Esther, who defined this phrase as her ‘motto’, keeping busy entailed her organising group activities, assembling Christmas boxes for a charity appeal, and getting out and about every day. In our first interview with Esther, she said:

I do mostly all my own food. I go down the dining room once a week maybe, you know … I think it gives you something to do and it keeps your mind occupied … Because I was – my moles were – I've had cancer twice but that's not a problem. Alzheimer's, I'm scared stiff of Alzheimer's … So, I went to my doctor and asked his advice. He said keep busy. That's why I go out every day … just go out just for a little while.

Several other residents at Sites A and B stressed the importance of ‘not sitting … and waiting for God’ (Esther). Here, keeping mentally active and socially engaged was framed by residents as a way to avoid isolation and boredom and, in turn, mental and physical decline. Pauline, a resident who organised activities at Site B, for example, said, ‘how on earth can you stay in 24/7 … that would drive me nuts’ and her fellow resident, Janice, described how she would knit clothing for care workers’ babies as a way to ‘keep occupied’.

Whilst for Esther and other residents at Sites A and B, keeping busy required self-organisation, good mobility and links to the external community, for residents whom we spoke to at Site D, being busy was seen as an inevitable consequence of living in the ECH scheme. Indeed, several residents at Site D joked about their need for a ‘day off’ from the scheme's constant stream of activities and events. Nigel said that he was yet to unpack all his possessions after living at Site D for eight months because there was ‘so much going on’ at the scheme. Likewise, when asked if there was enough to do at Site D, Gladys joked: ‘Oh, plenty. They have to make an appointment. My grandson will say “I can never get hold of you Nan, I shall have to make an appointment!”’. Exercise was also discussed by residents at Site D who, for the earlier part of our study, had access to an on-site gym and fitness instructor.

Kept idle

Keeping busy and certainly partaking in exercise, however, was not always possible for the residents whom we spoke to in all four of the schemes. In some cases, this was due to issues of mobility, disability or illness. For other residents, attempts to keep busy were hindered by the context in which they lived, either due to a lack of activities, a lack of care or support provision or changes to the way that support was funded, or the layout and design of the scheme. Residents at Sites A, B and C, for example, spoke about the impact which a lack of activities had on their feelings of boredom, loneliness and quality of life.

Residents across the four sites also referred to how the design and materiality of ECH could impact upon their ability to socialise and keep busy. Yvonne, at Site A, for example, spoke about how the heavy door to her flat had become a barrier to her ability to engage in activities and social events at Site A. In other cases, residents found it difficult (or impossible) to access certain areas. Several residents at Site D, for example, spoke about their long walk to communal areas and a large flight of stairs to one external exit. During our fourth visit to Site B, a broken lift meant that some residents were unable to leave their flats for several days. The study by Barnes et al. (Reference Barnes, Torrington, Darton, Holder, Lewis, McKee, Netten and Orrell2012) of the physical design of ECH has similarly drawn attention to how the built environment of ECH – heavy fire doors, inadequate storage and a lack of handrails, among other things – can present barriers to independence.

In recent years, there has been increased recognition of the importance of creating spaces where materiality and design facilitate, rather than hinder, the mobility and sociability of those residing in care environments (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Barnes, McKee, Morgan, Torrington and Tregenza2004; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Nettleton, Buse, Prior and Twigg2015; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Imrie and Kullman2016; Martin, Reference Martin, Bates, Imrie and Kullman2016). As these instances demonstrate, however, more needs to be done to translate this recognition into practice, bringing older ECH facilities in line with current developments.

Importantly, for residents in our study, keeping busy and engaging in activities was considered to be a way to avoid physical decline and, in turn, to prevent or delay the need for care or assistance. Whilst ECH sometimes facilitated these strategies (e.g. through the provision of activities), this facilitation was not consistent across the four schemes, across the four waves of our study or for all residents living in each scheme.

Resisting dependency

A third way in which some residents in our study exerted control over their changing care needs was by avoiding the purchasing of formal care until absolutely necessary. These residents either had an illness, disability or infirmity which restricted their ability to carry out certain tasks at the beginning of the study or developed one during the course of the research. Nonetheless, they took measures to prevent such infirmities from necessitating the uptake (or increase) of formal care provision. Whilst formal care assessments may have concluded that these residents had a need for care, the residents took steps to either prevent or reduce the impact which this need had upon their requirements for formal care provision. This happened in two key ways: adaptation and informal care arrangements.

Adaptation

There were examples of the first strategy, adaptation, across the four sites. Such adaptation was often employed to prevent the need for support with shopping or cleaning and often involved technological solutions or aids: Julie from Site B, for example, had reduced her hours of support provision after teaching herself how to shop for groceries online; some residents at Sites A, B and D purchased electronic scooters during the study; and residents at Sites B, C and D arranged the delivery of frozen meals when they were unable to cook. Joseph, at Site D, for example, said:

I cook for myself … Well I say cook for myself, I get most of them from Iceland. Meals for one. Beautiful, I can fill the freezer full of five or six meals and it's only about seven quid …The food [in the restaurant here] was great. I have no problem with the food it is just the fact that I like my one bit of independence that's getting my own meal when I want it.

Many residents who made adaptations in order to avoid formal care drew upon a similar discourse, and indeed were often the same individuals as those who stressed the importance of ‘keeping busy’. Sally, a resident at Site B who had chronic leg pain and mobility problems, was one of these individuals. She said:

I don't have any carer here, no. I try and persist to do things myself. Keep me going. ’Cause I think if you just stop, that's it isn't it? And I think, you must. I know it's a bit hard sometimes but you've got to do it because otherwise you just crack up and I don't want that.

For many residents, avoiding formal care was therefore viewed as a way to keep active and maintain independence. Interestingly, however, residents did not always frame receiving care and support from friends or family members in the ‘dependent’ way that they framed formal care.

Informal care arrangements

Across the four sites, many residents drew upon the informal care and (more often) support from family members or from other residents as an alternative to receiving formal care. Often, this took the form of grocery shopping, cleaning and household tasks, assistance with finances, and transportation. Sally, mentioned in the quote above, for example, explained that, whilst living in ECH meant that she was ‘not dependent on [her children] … as much’, her daughters also enabled her to ‘persist’ with doing things herself rather than drawing upon formal care provision:

My daughters take me shopping. Or else I would have problems there. They take me or if I can't go they get it [groceries] for me. But I try and go [out] if I can just to be out for a few hours. So I got no problems there, my daughters are very, very good and I just get on with it.

When asked if they received any care or assistance, many residents explained that they did not but that, on occasions where they did require assistance, they would ‘only have to pick up the phone’ and a family member would ‘be [t]here’ (Alison, Site D). Similarly, Nancy, from Site D, explained:

At the moment I can do everything myself, I mean things are getting more difficult … I can see the day coming when I will have to ask for some help … if I want anything done my brother-in-law, or one of my relatives would come and do it for me you see rather than me, but I know I can ask them and the staff here are super.

Whilst some residents spoke about their desire to resist becoming dependent on their families and expressed that they did not want to ‘pester’ (Barry, Site B) or ‘impose on’ (Eileen, Site D) them, more often, residents expressed a preference for drawing upon familial networks for support before drawing upon formal care provision.

Other ECH residents resisted drawing upon the informal care and support of family members or formal care provision by depending on each other. For example, Norma at Site B picked up shopping for other residents and visited one resident after a stay in hospital, while Mabel at Site D helped another resident with opening jars and removing her jumper each night. More formally, some residents at Site D became official volunteers for the site's care provider, assisting other residents with activities and outings. For many residents at the four schemes, support from other residents came during times of ill-health. June, who lived at Site B, for example, said:

Do you know a lady in my little flats, Thursday, she brought me round a cream rice pudding, she knew I weren't eating and she said ‘try this’ … I know they're always pleased to see me [in the lounge] and if I don't go down there I get phone calls to see if I'm alright and the lady in that flat up there said that I could ring her at night or day it doesn't matter what time, now there's not many people that say that is there?

For others, ECH impeded, rather than enabled, their attempts to resist dependency by avoiding formal care provision. This was particularly the case at Site B where, in accordance with the local authority policy in Area 1, new funded residents were only accommodated if they required five hours of formal care provision per week. Iris, from Site B, described these criteria to us in her first interview:

She [care assessor] said, ‘the only thing is you've got to have five hours care a week’. I said, ‘Five hours care.’ I said, ‘I don't need care.’ I said, ‘I can look after myself.’ Well she said, ‘Well that's the new ruling that has been brought in, so there's no option, you know.’ Oh well, I said, ‘If that's the case what am I going to have care on?’ So of course she explained. She said, ‘Well you can have the carers come in on a morning … On a Wednesday you can have a bath, so that's an hour there, they allow for that, so that was three hours. An hour they take to come in and do the cleaning and then they allow an hour for the laundry … I mean it don't take an hour, but that's what they allow the hour for. So that was the five hours, so that was what I had to do.

It is not clear why Iris was accommodated at Site B if she did not meet the assessment criteria in terms of her care needs, but this does draw attention to the difficulty of assigning specific amounts of time for particular care tasks, without taking account of individual variation or preferences.

Managing care provision

For other residents at the four schemes, accepting a need for care did not signify a sacrificing of all control. Indeed, whilst an individual's need for care may result from their loss of control over ‘body’ or ‘self’, the provision of care can bring new possibilities for control with it. Such control was visible in instances where residents had a say in specifying the timing and content of their care. Iris, who was mentioned in the previous paragraph, for example, spoke at length about how whilst she accepted that she was required to receive five hours of care per week at Site B, she also carefully adapted the content of these five hours of care when her needs changed:

Well they don't do the laundry now … I've had to start wearing these elastic stockings. And they come in on a night, because I cannot take them off … It takes them about five minutes, but the least time they can charge is a quarter of an hour. So of course, that was put down. Well I went to [manager] and I said, ‘well fair enough, if I've got to have it, I've got to pay for it.’ But I said, ‘I don't want to pay more than the five hours a week, can that be taken off of something else?’ So, it was worked out, they'd take out the laundry, they don't do the laundry now. Instead of getting an hour cleaning I get three-quarters of an hour. And, oh quarter of an hour for a bath, instead of an hour. So, they've cut it down, it's still five hours.

Other residents, across the four schemes, spoke about how they were able to reduce the hours of care which they received, alter which tasks were carried out by care workers and alter the timing of their care. In contrast to Gilleard and Higgs’ (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010) assertion that a loss of one's ability for self-care leads one to transition into the fourth age, some participants in our study were at once both unable to carry out all activities without assistance from others and able to exert control and self-determination when it came to planning and managing their care.

This ability to maintain control despite an inability for self-care was a positive aspect of ECH which appeared to be dependent on whether residents’ particular needs or preferences could be accommodated within care workers’ scheduled hours of work. For example, at Site B, there was sufficient room to manoeuvre the timing of Iris's care to accommodate a 15-minute appointment during the evening. This extends existing claims that for older people receiving care, asserting ‘control’ can move beyond self-management and include delegating their care and responsibilities elsewhere and deciding when support is delivered (Bamford and Bruce, Reference Bamford and Bruce2000; Gabriel and Bowling, Reference Gabriel and Bowling2004; Callaghan and Towers, Reference Callaghan and Towers2013; Lloyd et al., Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014).

For other residents, however, the provision of care in ECH was not flexible enough to meet their requirements. This was particularly the case when it came to care in the evenings or at night, when a lack of staff meant that the timing of care did not align with residents’ preferences or needs. At Site C, for example, Patricia said: ‘they come in at eight o'clock to get me into my night clothes ready for bed. I don't go to bed at that time but that's my time and I'm sitting watching television by then’. At Site C, and the three other sites, the provision of care was organised into what care workers and managers at three sites termed ‘runs’. Across all four sites the approach to the organisation of care was ‘time-and-task based’ (Garwood, Reference Garwood2010), which severely impacted upon the control that residents could exercise over both when their care was to be carried out and what tasks would be undertaken.

The experiences of these residents may appear to provide evidence of the institution's role in propelling individuals into the fourth age. Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010) describe the institution as a key propeller of the individual's progression into the fourth age, suggesting that it is health and care professionals who determine whether someone is of the fourth age. That ECH is claimed as a potential solution to some of the problems associated with more traditional care environments, such as nursing and residential homes, presents it as a possible form of housing with care that does not automatically cause residents to enter the fourth age. What we see in some of these examples, however, is that the self-management of care envisioned by proponents of ECH is not always realised and, instead, an inflexible organisation of care into ‘runs’ takes away residents’ ability to make choices or remain independent.

Conclusions

Carrying out in-depth, qualitative interviews with older people over the course of 20 months made clear the mutable nature of resistance and resilience in later life. For the older people in this study, feelings of control and independence were not static states which receded at a clear border between the third and fourth age. Like Grenier's (Reference Grenier2012: 177, 170) participants, residents’ accounts of later life in ECH were ‘layered with complexity’ and troubled the ‘polarisation of the third and fourth age’ which has been presented in previous literatures. In the context of ECH, our findings show how several organisational factors can work together to either facilitate or impede older people's attempts to avoid decline, resist dependency or manage their care provision.

Our study reaffirms that, rather than propelling older people into the fourth age, moving into ECH can be the product of an agentic decision, which is made as an attempt to plan for the future and maintain independence (Bäumker et al., Reference Bäumker, Callaghan, Darton, Holder, Netten and Towers2012; Darton et al., Reference Darton, Bäumker, Callaghan, Holder, Netten and Towers2012). Moving into ECH in an agentic manner, however, was not possible for all residents across the four schemes. Two related factors which mitigated residents from expressing agency in this way were the funding criteria of the schemes and, in turn, their means of recruiting residents. Whereas, at Site D, many self-funding residents had attended scheme open days and signed a waiting list way in advance of moving in, many individuals moving into Sites A, B and C were reliant on meeting their local authorities’ funding criteria. For residents at Sites A, B and C, the move into ECH was therefore more likely to be a reactive one in which they were given less choice. This reaffirms that there is a disparity of experiences between older people who are tenants living in ECH schemes which act as providers of social housing and older people who are able to actively choose to become outright owners of apartments in luxury ECH schemes (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Darton, Cameron, Johnson, Lloyd, Evans, Atkinson and Porteus2017).

Providing further evidence that the barrier between the third and fourth ages is not an unmalleable ‘cliff edge’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010), many residents in the study described their successful attempts to keep physically active and to avoid social isolation despite their ailments. Impacting upon both of these things, however, was the availability of social activities and the materiality and architecture of the schemes, such as long corridors, heavy doors and a lack of exercise facilities. This demonstrates a clear need for researchers and care planners to continue to attend to the materiality and design of care environments, which impact heavily upon older people's capacity to resist decline and dependency (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Nettleton, Buse, Prior and Twigg2015; Bates et al., Reference Bates, Imrie and Kullman2016; Martin, Reference Martin, Bates, Imrie and Kullman2016).

Moreover, many residents in this study – perhaps in an attempt to distance themselves from notions of dependency (Grenier, Reference Grenier2012) – avoided formal care provision until it was considered absolutely necessary. This shows how, for some older people, it is not the existence of care needs, but the receipt of care provision, which is associated with dependency and decline. Likewise, when residents in our study were no longer able to solely self-care or receive support from family or friends and, instead, were required to draw upon formal care provision, this did not mean a withdrawal of all agency. In fact, for some residents, the receipt of formal care provision created an interdependence that provided an opportunity for more agency. This stands in contrast to previous suggestions that it is the receipt of formal care provision which characterises an older person as of the fourth age. Growing old in ECH is not a straightforward tale of decline or a lack of agency; indeed, agency and choice – for the residents in this study, at least – were not simply luxuries reserved for the healthy. If ECH is to facilitate residents’ expression of agency in this way, then care provision must be flexible enough to respond to residents’ needs and choices.

In this paper, then, we have recognised the role of personal agency in ECH, which is influenced or mitigated at different moments depending on the intersected factors outlined above. For participants in this study, growing older did not amount to a ‘cliff edge’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010). Instead, residents were able to exert agentic choice at different moments, although the range and degree of such choice varied from resident to resident and from scheme to scheme. Ensuring greater equity in this respect will require: making ECH a viable option for all older people in order to reduce reactive placements; attending seriously to the materiality and architecture of ECH settings; offering opportunities to ‘keep busy’; and ensuring that we give older people as much control as possible to manage how and when their care is provided.

These proposals, though, are threatened by a context which is hostile towards older people. Whilst organisational practices in ECH schemes can aid residents’ attempts to manage their changing care needs, these facilitating practices are threatened by external pressures, such as funding changes, which result in a more time- and task-oriented approach to service provision. The many challenges identified throughout this paper are significantly related to the degree and source of ECH schemes’ funding. Austerity policies – including service cutbacks and reduced social care funding – have a cumulative impact on the ability of older ECH residents to hold and enact agency. This flags up the issue of lifetime inequities and cumulative disadvantage among the older population (Grenier, Reference Grenier2012), which deserves more attention than it has been afforded here. Nonetheless, what this study makes clear is that, whilst ECH may prevent some older people from transitioning into the fourth age without agency, it requires both adequate resourcing and a policy environment which is aligned with its goals if it is to live up to this promise.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, School for Social Care Research (grant number CO88/CM/UBDA-P73). Financial sponsors played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing of the study.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Social Care Research Ethics Committee (reference number 15/IEC08/0047).