The Department of Health first outlined its plan for the implementation of activity-based funding in 2002 (Department of Health 2002). This was a radical move from previous ‘block contract’ arrangements where hospitals were given fixed amounts of money irrespective of their level of activity. Some of the advantages and disadvantages of the two systems are highlighted in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Block contracts and activity-based contracts

Payment by results (PbR) is part of the National Health Service (NHS) modernisation in England. It is a new way of paying both hospital- and community-based health services, with payments based on the amount of work done in line with a national tariff. To gain a better understanding of PbR, it is useful to discuss its three components (Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health 2004).

-

1 Activity-based funding: providers will be paid according to the volume of work done. Thus, a greater workload leads to a greater income and vice versa. This replaces the block contract system where there was no link between volume of work and income.

-

2 Healthcare resource groups (HRGs) and diagnosis-related groups (DRGs): HRGs categorise patient events that have been judged to consume a similar level of resources. For example, there are a number of different hip-related procedures that all require similar levels of resource which may all be assigned to one HRG. These groups cluster together related health conditions based on diagnosis (in which case they are termed DRGs) and/or needs, and allow for complexity of the condition and the care required. For every acute provider hospital spell (a period of care from admission to discharge), the patient is assigned an HRG code using a software called the Grouper.

-

3 Payment according to a national tariff: all providers (including those from the NHS, independent and third sectors) will be commissioned according to a national tariff which will introduce uniformity and will also be advantageous for commissioners as they will not need to ‘haggle’ over costs, but concentrate on the quality of services provided instead. However, other costs from activities such as teaching, training and research (which happen in most NHS trusts) are not considered.

The aim of PbR is to provide a transparent, rules-based system which rewards efficiency, supports patient choice and diversity, encourages activity for sustainable waiting time reductions, is linked to activity and is adjusted for case mix.

The international context and evidence

Payment according to DRGs was first used in the USA for acute in-patient services paid for by Medicare (a government-financed health insurance mainly for elderly people). The system has also been used in various ways in 15 other countries. A review of PbR showed improved cost-efficiencies by reducing the duration of in-patient stays and increasing the use of day surgeries and out-patient care. It also decreased waiting times significantly when compared with services commissioned through block contracts (Reference Docteur and OxleyDocteur 2003).

Potential risks

The advantages outlined above are not foolproof and one must consider the risks associated with implementation of the scheme in NHS services. The most obvious are:

-

• ‘cream skimming’ – providers may decide to treat patients with conditions that are ‘straightforward’ to manage and have fewer associated complications;

-

• ‘quicker and sicker’ – the duration of in-patient stays may have been reduced considerably with the implementation of PbR, but the question as to whether patients were prematurely discharged has not been investigated;

-

• ‘DRG creep’ – there is a possibility that providers may falsely assign DRG codes that allow them to charge more for their services;

-

• ‘cost spiralling’ – with income linked to volume of work, providers might be tempted to increase their activity levels, which would result in difficulties in paying for the work done because of increased costs.

The above risks can be circumvented with appropriate safety systems in place such as protocols to regulate admissions and the quality of care provided, independent audits of coding data, and risk-sharing agreements between commissioners and providers. To prevent inappropriate and excessive DRG coding, on occasions commissioners put a ceiling on the level of a particular high-cost hospital activity.

Payment by results in mental health

There are many difficulties in applying PbR in mental health services (Box 1). For example, not every patient seen in secondary mental health services will fit naturally into a clinical cluster. Interventions used in mental health services may not all fall within an established category of interventions. There is significant variability in service provision, resulting in difficulties in arriving at a national tariff for mental healthcare delivery. Furthermore, investment in IT systems has been patchy across the NHS in England and Wales, causing significant difficulties in gathering meaningful data.

BOX 1 Difficulties in applying PbR for mental healthcare

-

• Differing presentations of the same illness in different individuals

-

• The chronic relapsing and remitting nature of certain mental illnesses

-

• Variations in treatment practices among clinicians

-

• Variations in service provisions in different regions

-

• The relationships between interventions and outcomes are not clear

-

• Difficulty in costing the community element of care, which in most circumstances may be multi-agency

-

• A lack of minimum data-sets for case-mix development

Despite these complications, it is imperative to develop PbR for mental health. Not progressing in this direction could result in further reduction in resources for mental health services. There is anecdotal evidence that mental health funding has already been squeezed to accommodate payments in the acute sector (Reference FairbairnFairbairn 2007).

Payment by results in mental healthcare needs a more pragmatic approach than the statistical methods used to develop HRGs. The mental health PbR system is based on the Care Pathways and Packages approach, developed by clinicians in South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust as part of a service redesign to improve efficiency.

There are currently six mental health trusts in England piloting PbR. They have identified 21 empirically derived care groups/clusters. A modified version of the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales – HoNOS-PbR – is used as a clustering tool to allocate individuals to different clusters. Tariffs are derived from the respective cluster, weighting on the complexity or severity of the condition and duration of treatment. The tool has been modified throughout this process and is now called the Mental Health Clustering Tool.

The Department of Health (2010) recently published an implementation plan for PbR in mental health as outlined in Box 2. The application of PbR will start with mental health services for working-age adults and older people; only those children who are receiving care within a specialist adult mental health service such as early intervention services will be included (Department of Health 2010). Other mental health services such as child and adolescent mental health services and learning disability services are not currently included in the PbR mental health pilot programme.

BOX 2 The revised time line for implementing PbR in mental health

2010/2011 – Clusters will be available for use and reference costings

2011/2012 – All service users accessing mental healthcare to be allocated to a cluster

2012/2013 – Local cost for clusters to be established

2013/2014 – The earliest possible date for a national tariff for mental health (if evidence from the use of a national currency presents a compelling case for a national price)

Payment by results in learning disability services

The application of the PbR model in learning disability services is likely to be even more complex than in other mental health services (Box 3). The high prevalence of mental health problems/challenging behaviours, comorbid physical health problems, communication problems and sensory impairments (Reference SmileySmiley 2005), as well as environmental issues, pose real challenges for developing meaningful clinical clusters in this population. The atypical presentations, along with lack of standardised diagnostic criteria, make the diagnosis of mental health problems in this population particularly difficult.

BOX 3 Difficulties in applying PbR to learning disability services

-

• Significant variations in presentation and the course of illness

-

• There are no acceptable outcome measures

-

• Nature of interventions required and the outcome are influenced by the complex interplay of physical health, mental health and social factors

-

• Interventions are often not standardised or clearly defined. Professional opinion on the nature of intervention required can vary significantly

-

• Treatment is provided in many settings, which affects the cost

-

• Considerable variations in the service models exist across the country

-

• Problems are often chronic or episodic

-

• Clinical information is not gathered in a standardised manner

-

• Not all activity is related to mental health needs

Historically, specialist learning disability services have been commissioned through block contracts. There are variations in the nature of service provision and the professional roles between services (Reference Cooper and BaileyCooper 1998), which make the development of a national tariff particularly difficult. This variation is reflective of the historical evolution of learning disability services and demonstrates the lack of a national steer for a service provision model. Depending on the host organisations, learning disability service provisions have developed in different ways. Although some services are part of mental health trusts, others are managed within primary care trusts or as part of local authorities.

The PbR pilot project

The Department of Health has set up two pilot sites for the application of the PbR model in learning disability services (Leicester and Birmingham). In response to this, the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Faculty of the Psychiatry of Learning Disability established a national steering group, the membership of which includes interested clinicians and representatives from the two pilot sites. Through a process of focus group (clinicians, commissioners and finance staff) discussions and mapping of service users’ conditions and needs, eight clinical clusters have been established within which the majority of patients accessing learning disability services can be placed (Box 4). Care pathways have been developed for the eight clinical clusters.

BOX 4 Eight clinical clusters for learning disability services

-

1 Severe mental health problems

-

2 Common mental health problems

-

3 Behaviour problems (includes autism-spectrum disorders)

-

4 Personality disorder and offending

-

5 Degenerative conditions/dementia

-

6 Neurological conditions (including epilepsy)

-

7 Disability-related health problems

-

8 General health problems

However, it was felt that within these clinical clusters there would be a significant variation in the level of need. It was agreed through consensus that needs should be added as a second dimension to the clusters. Through a process of further discussion, the focus group established provisional criteria for two categories within each cluster based on clinical needs (high and low) (Box 5). A good level of interrater reliability was achieved among different professional groups on consistency of how to rate needs.

BOX 5 Criteria for different level of need

High

-

• Contact at least once a fortnight

-

• Multiprofessional involvement

-

• Enhanced level of care programme approach

-

• Mental Health Act status

-

• Significant risk to self or others

-

• Disengagement from service

-

• Non-adherence to medications

-

• Need for out-of-hours support

-

• Need for in-patient admission

Low

-

• Less frequent contact

-

• Not on care programme approach

-

• Score low on risk assessment

-

• Engaged and cooperative with care

-

• Can be managed in the community without needing multiprofessional involvement

Estimating the reference cost

A baseline evaluation of reference cost (cost per activity by different professional groups) based on the current service-commissioning model (the block contract) was undertaken (Reference Bhaumik, Devapriam and HiremathBhaumik 2009). The findings revealed significant variability in cost per activity across different professional groups, thereby indicating differing pay structures and variability in performance. This model was applied to both high- and low-need groups in all clusters.

In a prospective piece of work (Reference Bhaumik, Devapriam and HiremathBhaumik 2009), patients were allocated to the eight clinical clusters based on their diagnosis and level of need in accordance with the criteria in Box 5. The activity figures were measured and the costing model was applied, which showed significant variability in treatment costs, especially in high and low needs for all clinical clusters, with the exception of the cluster for general health problems.

Care pathways

To develop valid currencies (DRG codes) as well as tariffs in learning disability, service provision would need to be based on care pathways. Pathways based on a stepped care model would ensure the right interventions in a timely manner by the right professionals, thereby reducing the long waiting time and duplication of work.

A care pathway specifies the interventions and care required, with a clear time frame and standards to reduce unnecessary variations in the delivery of care, to achieve the best outcome for the patient. It can be an effective vehicle to implement evidence-based/consensus guidelines in everyday practice. All professionals within a service as well as all services within an area can be given a clear expectation of what needs to be delivered as part of the care pathway, avoiding gaps within or between services. Care pathways aim to:

-

• minimise inconsistencies in care and improve the overall quality of care received

-

• reduce gaps in service provision

-

• improve efficiency by using a stepped care model approach.

Limitations include:

-

• if interpreted rigidly, care pathways may reduce the flexibility of treatment approaches and thereby may not be conducive to person-centred care

-

• it may not address the multiple complex needs of service users who could fit into more than one care pathway

-

• an over-idealistic care pathway may be difficult to implement.

Stepped care model

Where there is a significant difference between demand and availability of services such as psychological therapies and care of long-term conditions, stepped care models have been proposed as a way forward (Reference Bower and GilbodyBower 2005). In stepped care, service provision starts with the least intensive intervention, reducing the demand for more intensive care. The advantages of this for long-term conditions are the focus on early interventions that minimise complications and disability, involvement of patients and carers through self-guided care and the potential for getting greatest benefits from the limited resources available.

Tiered care model

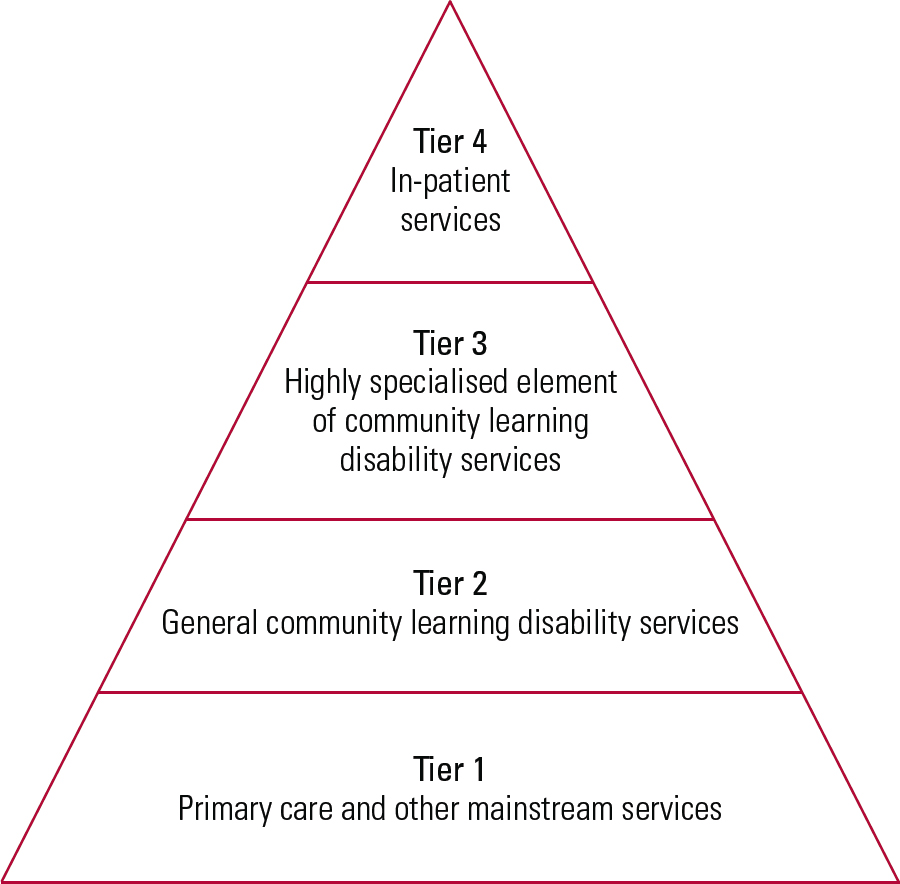

A tiered care model is often used to describe the organisational change required to implement the stepped care model. Tiered service provision can be described as a pyramid: making less intensive interventions widely available to all and progressively reducing the number of people who would need more specialised services as you progress up the tiers.

FIG 1 Tiered care model (Faculty of the Psychiatry of Learning Disability 2011).

Figure 1 shows the tiered care model that was developed initially in Leicester and subsequently modified and incorporated into the Faculty of the Psychiatry of Learning Disability’s report (2011).

Tier 1

Includes primary care and other mainstream services and is the tier of service provision that serves the general health, social care and educational needs of people with intellectual disability and their families. The community learning disability team and the psychiatrist have limited direct clinical contact in this tier, but are involved in activities such as training and support of professionals in primary care and other mainstream secondary care services.

Tier 2

Tier 2 is general community learning disability services. At this level the person with intellectual disability starts to use specialist services. Most specialist services are provided jointly between health and social services, or are moving towards such a model.

Tier 3

This is the highly specialised element of community learning disability services and includes areas such as epilepsy, dementia, challenging behaviour and out-patient forensic services.

Tier 4

Includes all specialist in-patient services for people with intellectual disability, ranging from local assessment and treatment services to high secure forensic services.

Conclusions and the way forward

For learning disability services, the overlap between physical healthcare, mental healthcare, psychological and social factors poses significant difficulty for the development of meaningful clinical clusters for the successful implementation of PbR. Clusters that have been developed are based on clinical consensus. Although the focus is primarily on diagnostic groupings and not on needs, the variation of needs within each cluster is captured using high- and low-need categorisation. In addition, it is recognised that many service users will fit more than one cluster at any given time (e.g. challenging behaviour, epilepsy).

The successful application of the PbR model in learning disability services would require a clustering tool. Currently, the validity of HoNOS for people with intellectual disability as a clustering tool is being explored. However, early indications are that this may prove to be more difficult than the use of HoNOS-PbR for mental health.

The nature of learning disability service provision is such that many individuals remain active within the service for a long period and therefore discharge back to primary care is not a routine practice in many places. This also partly reflects the reluctance of primary care services to take on the responsibilities for patients with intellectual disability and mental health needs. Fortunately, the situation is changing, with increasing awareness of learning disability issues among primary care clinicians following the publication of Healthcare for All (Reference MichaelMichael 2008). Another significant issue in applying the PbR model for learning disability services is the overlap between health and social care elements in some areas. Hence, clearly identifying health and social care costs separately may prove to be difficult.

In addition, models for provision of specialist learning disability health services vary widely and applicability of a PbR model may result in differing outcomes depending on where services are hosted, catchment populations (urban v. rural) and whether trusts are teaching or non-teaching. The inherent risk of applicability of the PbR model lies with the fact that many resource-starved services may be further deprived if commissioners use this model to reduce resources even more rather than to improve service provision. Therefore, the main impetus of this model should be on quality, activities and outcomes, not primarily on efficiency savings.

In our opinion, the way forward is to move towards a care pathway-based service delivery along with a single-point-of-access system for all referrals, and a core business model that has patient experience and outcome in the heart of its vision and strategy.

The financial model applied to determine the reference cost in the pilot centres in Leicester and Birmingham is rather primitive at this stage and needs further refinement to reflect the range of service provision in different parts of England and Wales. Overhead costs in the NHS are quite high owing to several factors including corporate overheads, estates and teaching and training. This puts services at a disadvantage in a competitive market where commissioning is based on a tendering process. However, there may be other reasons for the high reference costs, including inadequate recording of activities or of time spent indirectly on patient contact (such as travel, telephone calls, attendance at case conferences and giving informal advice). In addition, this might also reflect inefficiency within the services. All these factors imply that a good IT system and clinicians’ awareness of recording activities is absolutely essential for applying the PbR model.

We believe that a campaign for ‘log it or lose it’ should be a central thrust for each trust to get closer to true activity monitoring.

The pilot centres have now managed to combine the care pathway-based service provision with that of the PbR model and the next stage of the pilot work involves prospectively applying the PbR model with costing for geographical areas where care pathways are currently piloted. We plan to monitor this prospectively for the next 6 months and arrive at a reference cost for patients’ journeys through care pathways. This will also help us to identify whether the PbR model in learning disability services will lead to any efficiency savings for services.

Ultimately, the quality of the clinical care and the relationship between the clinician and the patient is paramount in making a treatment a success or a failure. We wish to highlight the fact that the PbR model is not the solution for all existing problems.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Payment by results (PbR) may be expected to:

-

a encourage multidisciplinary working

-

b be conditional to positive clinical outcomes

-

c result in longer waiting times

-

d establish a care pathway-based approach to assessment and treatment

-

e be based on local costs.

-

-

2 The aim of PbR is to provide a transparent, rules-based system which:

-

a rewards efficiency

-

b facilitates research

-

c encourages teaching and training of professionals

-

d promotes a return of surplus income

-

e creates opportunities for local employment.

-

-

3 The most obvious risks of the PbR model are:

-

a compromise in patient safety

-

b longer in-patient stays to improve incomes

-

c manipulation of diagnosis-related group (DRG) coding to charge more for services.

-

d cost-sharing with service users

-

e compromise in the autonomy of front-line medical staff.

-

-

4 Difficulties in applying PbR in learning disability services include:

-

a shared budgets with local authorities

-

b variations in clinical practice and service provision

-

c lack of accessible information to service users and carers

-

d many patients with intellectual disability live in residential care run by private providers

-

e preferential funding to mental health problems over complex needs.

-

-

5 Care pathways:

-

a are prescriptive and rigid in nature

-

b are an important aspect of clinical governance

-

c incorporate quality maintenance and improvement measures

-

d are unique to the specific healthcare group and do not interact with other care pathways

-

e are based on a national framework.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | a | 3 | c | 4 | b | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.