1 Introduction

In this Element, we introduce a family of approaches that regard constructions – that is, form–meaning pairs at various levels of abstraction and complexity – as the main units of linguistic knowledge. Traditional approaches to grammar often assume that our knowledge of language consists of two components: the lexicon as a repository of morphemes, words, and a very limited set of idioms, on the one hand, and the grammar as a set of rules for combining the items in the lexicon on the other (see e.g. Reference PinkerPinker 1994; Reference TaylorTaylor 2012). In such approaches, the lexicon is usually kept at a minimum – as Reference Di Sciullo and WilliamsDi Sciullo and Williams (1987: 3) famously put it, “[t]he lexicon is like a prison – it contains only the lawless, and the only thing that its inmates have in common is lawlessness.” Constructionist approaches take a radically different stance. Their starting point is the observation that there is much more idiomaticity in language than is usually assumed. Broadly speaking, idiomatic units are complex constructions whose meaning cannot be fully derived from their constituent parts (but see Reference WulffWulff 2008, Reference Wulff, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013 for a more nuanced treatment of idiomaticity and its relation to compositionality). Consider, for example, the much discussed way-construction, exemplified in (1) (all from the News on the Web corpus, Reference DaviesDavies 2016–).

a. Mr. Musk bluffed his way through the crisis. (October 5, 2018, US, MarketWatch, NOW corpus)

b. Last month Tesla CEO Elon Musk bullied his way to reopening his electric car factory in California ahead of local health officials’ recommendations. (June 11, 2020, KE, nairobiwire.com, NOW corpus)

c. Tesla founder and CEO Elon Musk teased his way through the car’s introduction, showing pictures of the company’s past (April 1, 2016, PK, BusinessRecorder, NOW corpus)

d. Elon Musk tweets his way through his pending Twitter acquisition. (May 21, 2022, US, wral.com, NOW corpus)

As Reference Israel and GoldbergIsrael (1996) points out, one important feature of this construction is that it always entails the subject’s movement (in a literal or metaphorical sense), even if the lexical semantics of the verb do not imply any kind of movement. Thus, the meanings of the sentences in (1) cannot necessarily be derived from the meanings of their constituent parts. In these examples, the whole is more than the sum of its parts – in other words, we are dealing with structures that are not fully compositional. As we will show in Section 2, the insight that noncompositionality is more ubiquitous in language than one might think was one of the main starting points of constructionist approaches. Language, on this view, is highly idiomatic. Constructionist approaches therefore depart from the classic position that words and morphemes are the main “building blocks” of language that are combined via a set of rules, and instead propose a joint format for the representation of meaning-bearing units of varying sizes and at different levels of abstraction: constructions.

Speaking of “constructionist approaches” underlines that Construction Grammar (CxG), which has grown into a large research field over the last decades with a variety of journals, textbooks, and book series dedicated to it, is not a uniform paradigm but has rather developed into a heterogeneous set of “Construction Grammars,” plural (see e.g. Reference Hoffmann and DancygierHoffmann 2017a, Reference Hoffmann and Dancygierb). While different approaches differ substantially in some of the assumptions they make as well as in their goals, Reference Goldberg, Hoffmann and TrousdaleGoldberg (2013) and Reference HoffmannHoffmann (2022: 10–16) summarize four basic assumptions that are common to all “flavors” of Construction Grammar, in addition to the basic concept of linguistic constructions:

They do not assume a strict division between lexicon and grammar but instead postulate a lexicon-syntax continuum.

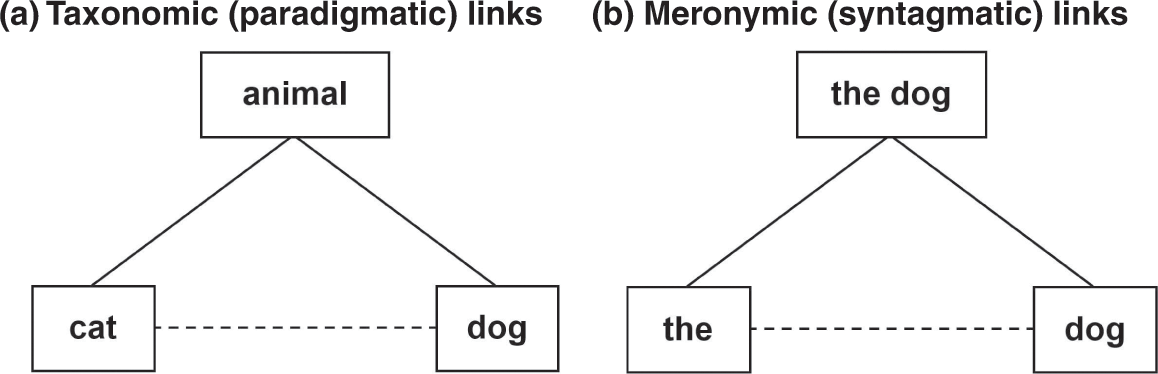

They assume that constructions do not exist in isolation and that our knowledge of constructions should not be conceived of as an unstructured list (as is sometimes the case in conceptualizations of the mental lexicon). Instead, they are organized in a taxonomic network, a construct-i-con. We will deal with the inner workings of this “grammar network” (Reference DiesselDiessel 2019) in Section 4.

They are surface oriented, that is, they do not posit some sort of “deep structure” with abstract syntactic representations and operations. Instead, it is assumed that constructions emerge (historically) and are learned (ontogenetically) via generalizations over concrete instances that language users encounter.

Given this surface orientation, they do not assume a “Universal Grammar” that underlies all human languages but instead expect a considerable amount of cross-linguistic variability. To the extent that there are universals of language (see Reference Evans and LevinsonEvans & Levinson 2009 for a skeptical stance), they are explained as generalizations deriving from domain-general cognitive processes and functional pressures (Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2022: 16).

In the remainder of this text, we will give an overview of the historical development, the current state of the art, and potential future outlooks of constructionist approaches. Of course, many excellent introductions to the framework already exist: for book-length introductions, see Reference HilpertHilpert (2019) and Reference HoffmannHoffmann (2022); for chapter-length summaries, see Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and ÖstmanFried and Östman (2004), Reference Croft and CruseCroft and Cruse (2004: 257–290), Reference Croft, Geeraerts and CuyckensCroft (2007), Reference Diessel, Dąbrowska and DivjakDiessel (2015), Reference Hoffmann and DancygierHoffmann (2017a) and Reference Boas, Wen and TaylorBoas (2021); see also Reference Hoffmann and TrousdaleHoffmann and Trousdale’s (2013) handbook. Compared with these earlier overviews, our focus here will be especially on recent developments in the field, including current research topics as well as ongoing debates that yet need to be resolved.

In Section 2, we provide an overview of the genesis of CxG, before addressing varying definitions of the concept of “construction” and discussing the question of whether morphemes and words should also count as constructions. In Section 3, we compare different constructionist approaches with regard to three parameters: their degree of formalization, their research foci, and the methods they prefer to use. Section 4 focuses on the structure of the construct-i-con, addressing its psychological underpinnings and the different types of links it may contain as well as some open research problems (see also Diessel’s [Reference Diessel2023] contribution to the Elements in Construction Grammar series for an in-depth treatment of constructional networks). Finally, Section 5 discusses some further current developments in CxG, zeroing in on three research topics that have increasingly gained attention in recent years: linguistic creativity, multimodality, and individual differences between language users. Section 6 offers a brief conclusion.

2 Discovering Idiomaticity: The Case for Constructions

2.1 The Early Days of CxG

Historically, the emergence of CxG is closely connected to the endeavor of establishing a counterpart to Chomskyan generative linguistics, which was the dominant paradigm especially in North American linguistics for much of the second half of the twentieth century (see e.g. Reference HarrisHarris 2021).Footnote 1 While the concept of “constructions” in the constructionist sense as well as the term “Construction Grammar” emerged in the 1980s, especially in the works of Reference FillmoreFillmore (1988; Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore, Kay, & O’Connor, 1988) and Reference LakoffLakoff (1987), Reference Boas, Wen and TaylorBoas (2021: 43) points out that the intellectual roots of CxG – and of its “sister theory,” frame semantics – lie in Reference Fillmore, Bach, Harms and FillmoreFillmore’s (1968) seminal paper “The Case for Case.” Specifically, he argues that the idea of “deep cases” foreshadows what later came to be known as semantic roles, which in turn play a key role in the interaction of verbs and constructions in CxG. But while the notion of “construction” already appears in earlier works, Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al.’s (1988) paper on the let alone construction is nowadays usually seen as the key starting point of CxG (see e.g. Reference Boas, Wen and TaylorBoas 2021: 49).

Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al. (1988) argue that idiomaticity is not just an “appendix” to the grammar of the language – instead, idiomatic patterns are themselves productive, highly structured, and worthy of grammatical investigation. In the case of let alone, they argue that neither can its properties be exhaustively derived from its lexical makeup and grammatical structure, nor can it be treated as a fixed expression. At the syntactic level, Fillmore et al. analyze let alone as a coordinating conjunction; at the semantic and pragmatic level, they see it as a paired-focus construction that evokes a certain scale. For example, in (2a), “taking the first step” and “taking the second step” can be interpreted as the contrastively focused elements, and as points on a scale. In (2a), this scale is fairly obvious, as it is in (2b), where approach and equal can be considered classic examples of lexical items that form a so-called Horn scale, that is, a scale where the stronger term entails the weaker one while the weaker term implicates the falsity of the stronger one (e.g. <warm, hot>, <some, many, most, all>; see Reference CumminsCummins 2019: 49).

a. I barely knew what step to take first, let alone what step to take second, let us not talk about the third. (A08, BNC)

b. The old Herring and Addis tools were made with a finesse and temper that modern tools do not approach, let alone equal. (A0X, BNC)

c. [R]eference to its existence, let alone study of its function, has been sedulously avoided. (A69, BNC)

d. I don’t have time to feed the children, let alone prepare my lecture. (Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al. 1988: 531)

In some cases, however, the scales evoked by let alone are more complex, as (2c) and especially Fillmore et al.’s example (2d) illustrate: Here, the conjuncts – reference to its existence and study of its function in (2c), feed the children and prepare my lecture in (2d) – do not belong to the same semantic domain. Thus, the scales evoked by let alone can be strongly context-dependent.

Apart from let alone, Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al. (1988: 510–511) mention a number of other constructions in passing, some of which have been investigated in more detail in later constructionist work; for example, the what with construction (what with the kids and all; see e.g. Reference TrousdaleTrousdale 2012) and the incredulity response construction (Him a doctor?!?; see e.g. Reference Szcześniak and PachołSzcześniak & Pachoł 2015). Fillmore et al.’s article thus spawned a series of further constructionist analyses, starting in the early 1990s – for example Reference KayKay’s (1990) paper on even and Reference MichaelisMichaelis’ (1993) study of the English perfect construction – and growing in number ever since.

In the following, we cannot provide a summary of all the phenomena that have been studied from a constructionist perspective over the last thirty-five years, as there are too many. Instead, we will focus on the key notion of “construction,” exploring how the concept has developed over time in the context of the changes that CxG as a paradigm has undergone. In particular, we will focus on Reference GoldbergGoldberg’s (1995, Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2019) definitions of constructions, as the evolution of the concept in her writing arguably reflects important developments in CxG, which is why the different definitions she has provided over the years are often cited and compared to each other in introductory texts (e.g. Reference HilpertHilpert 2019; Reference Ziem and LaschZiem & Lasch 2013). We will also discuss what kinds of units can be seen as constructions, which naturally depends on the definition of construction that one adopts.

2.2 “Construction”: An Evolving Concept

A major contribution to defining the notion of construction was made by Reference GoldbergGoldberg (1995) in a monograph that also constitutes the first book-length summary of the constructional approach and can therefore be seen as a further milestone in CxG history.Footnote 2 In this book, Goldberg outlines many of the key issues that have been at the heart of constructionist approaches ever since: the important role that aspects of meaning (semantic and pragmatic) play in the analysis of grammar; the interaction between constructional meaning and verb meaning; the notion that constructions motivate each other within a network of stored knowledge (see Section 4); and a usage-based account of the partial productivity of constructions based on learning mechanisms such as indirect negative evidence (see Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2019 for a more recent account of this mechanism in terms of “statistical preemption”).

Crucially, Reference GoldbergGoldberg (1995) also proposes what may be the best-known definition of “construction”:

C is a construction iffdef C is a form-meaning pair <Fi, Si> such that some aspect of Fi or some aspect of Si is not strictly predictable from C’s component parts or from other previously established constructions.

The definition captures two central elements. First, drawing on the traditional concept of a Saussurean sign (Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1995: 6), constructions are regarded as units of form that inherently carry meaning, contrary to their generativist conception in terms of meaningless structural rules. In Goldberg’s approach as well as subsequent work, “meaning” has come to be understood in a broad sense, comprising lexical, semantic, pragmatic, discourse-functional, and social aspects, while “form” is usually taken to include phonological, syntactic, and morphological information (but see e.g. Reference Herbst and UhrigHerbst & Uhrig 2020 for discussion).Footnote 3 Second, Goldberg uses nonpredictability as a criterion for what counts as a construction and what does not: Any pattern that has “unique” properties that go beyond the properties of its subparts and those of other, partially similar, constructions is recognized as a construction in its own right. Nonpredictability is closely linked to the notions of idiomaticity and noncompositionality, which are also often used to argue for the construction status of a pattern (see Reference Pleyer, Lepic and HartmannPleyer et al. 2022 for the multifaceted meanings of “compositionality”). Crucially, however, the nonpredictability criterion applies not only to idiomatic constructions which, in previous generative work, had been relegated to the “periphery” of language (Reference ChomskyChomsky 1981); it also allows for highly frequent and seemingly “regular” or “core” patterns, such as the caused-motion pattern illustrated in (3), to be treated as constructions. The fact that (3b) implies a motion event, even though it contains an intransitive nonmotion verb, suggests that the “caused motion” meaning is associated with the construction itself and is not predictable from the lexical items it contains. As a result, Goldberg’s definition allows for a wide view of “constructions” that covers both broad grammatical generalizations and the many less-frequent idiomatic patterns whose role was emphasized by early CxG work.

a. Pat pushed the piano into the room. (Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1995: 76)

b. Sally sneezed the napkin off the table. (Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1995: 6)

Reference GoldbergGoldberg’s (1995) definition has, however, not remained unchanged over time; rather, it has continued to evolve as subsequent research has brought to light some of its limitations. First, scholars have come to agree that, apart from their nonpredictability, the frequency of linguistic patterns is another major determinant of their status as constructions. Early evidence that speakers track and record frequencies in the linguistic input came from studies showing that more frequent units tend to be phonologically more reduced than less frequent ones (Reference Bybee, Barlow and KemmerBybee 2000; Reference LosiewiczLosiewicz 1992). Moreover, the long-standing research on formulaic patterns in language (Reference BolingerBolinger 1976; Reference Kuiper and HaggoKuiper & Haggo 1984; Reference PawleyPawley 1985) has highlighted that speakers rely heavily on lexically fixed chunks in natural speech. As illustrated in (3) and (4), speakers routinely prefer certain frequent expressions over less frequent alternatives, even when the words they contain have similar meanings and they are both sanctioned by the same abstract construction, such as the noun-phrase construction in (4) and the transitive construction in (5). This suggests that speakers store highly frequent chunks as constructions in their own right, even when they can be predicted from their component parts or based on an abstract template they instantiate.

a. innocent bystanders (preferred)

b. uninvolved people (dispreferred)

a. it boggles my mind (preferred)

b. it giggles my brain (dispreferred)

(all adapted from Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2019: 53)

Apart from these fully lexicalized instances, there is also ample evidence that speakers encode frequency information about partially lexicalized subtypes of more abstract constructions. For example, Reference Gries and StefanowitschGries and Stefanowitsch’s (2004) corpus results indicate that speakers’ use of the ditransitive and the to-dative construction varies depending on the verb: While verbs such as give, tell, and show are more often used with the ditransitive, as illustrated in (6), verbs such as allocate, wish, and accord are preferably used with the to-dative, as in (7). Even though the sentences in (6) and (7) are all instances of more abstract generalizations, the fact that speakers prefer one variant over the other suggests that they associate distinct frequency-based information with each verb-specific pattern.

a. She told the children the story. (preferred)

b. She told the story to the children. (dispreferred)

a. She allocated the seats to the guests. (preferred)

b. She allocated the guests the seats. (dispreferred)

As a result, many researchers have argued for the existence of lexically specific constructions even when their form and meaning seem predictable from the more abstract schemas they instantiate (Reference Booij, Nooteboom, Weerman and WijnenBooij 2002; Reference Bybee and HopperBybee & Hopper 2001; Reference Langacker, Peña Cervel and de Ruiz Mendoza IbáñezLangacker 2005). An often-cited example is I love you (Reference Langacker, Peña Cervel and de Ruiz Mendoza IbáñezLangacker 2005: 140), which, due to its high frequency, is likely to be stored as a separate construction, even though it is fully compositional. Given this evidence, Reference GoldbergGoldberg (2006) proposed a modified definition of constructions, which explicitly incorporates the frequency criterion and which has again been widely used since:

Any linguistic pattern is recognized as a construction as long as some aspect of its form or function is not strictly predictable from its component parts or from other constructions recognized to exist. In addition, patterns are stored as constructions even if they are fully predictable as long as they occur with sufficient frequency.

But the story does not end there, and aspects of the 2006 definition have also come under scrutiny. Reference Zeschel, Evans and PourcelZeschel (2009), for instance, raises doubts about the use of the nonpredictability criterion for delineating constructions. In particular, he takes issue with the categorical nature of the criterion: By regarding patterns as either predictable or nonpredictable, analysts are forced to draw sharp distinctions between the features that set apart one construction from another and the ones that fail to do so. As Reference Zeschel, Evans and PourcelZeschel (2009: 187–188) argues, however, these decisions are often difficult to make because tests for the presence of a certain feature are not always available; because features might vary in their salience depending on the context; and because interindividual variation among speakers means that constructions are not really characterized by strictly necessary properties but rather by statistical tendencies. Similarly, with respect to compositionality, it has been argued that patterns are not either compositional or noncompositional but that compositionality is a matter of degree (Reference LangackerLangacker 2008: 169).

As an alternative to the nonpredictability criterion, Reference Zeschel, Evans and PourcelZeschel (2009) advocates the use of Reference LangackerLangacker’s (1987, Reference Langacker, Peña Cervel and de Ruiz Mendoza Ibáñez2005) entrenchment criterion, according to which a pattern is recognized as a construction if it is sufficiently entrenched, that is, cognitively routinized (on the concept of entrenchment, see e.g. Reference Blumenthal-DraméBlumenthal-Dramé 2012 and Reference SchmidSchmid 2017b). Since entrenchment is naturally a gradient concept, this view entails that the distinction between what is a construction and what is not may be continuous rather than categorical, with higher degrees of entrenchment providing increasingly stronger evidence that a pattern has construction status. Crucially, the entrenchment of a unit is commonly assumed to depend on several factors, among them the frequency and the similarity of its instances: The more instances a pattern comprises, and the more similar these instances are to each other (while being simultaneously dissimilar to instances of other patterns), the more likely speakers are to group them together under a construction (Reference Bybee, Hoffmann and TrousdaleBybee 2013; Reference SchmidSchmid 2020; see also Section 4.3 for discussion). Crucially, the notion of similarity is closely related to the nonpredictability criterion used in Goldberg’s earlier definitions: The more dissimilar a pattern is to already existing units, the less predictable it is. If, instead, a group of instances are highly similar to an extant construction, they can be subsumed under that generalization, thereby further strengthening it, rather than forming a construction in their own right. The entrenchment criterion, grounded in similarity, can therefore be used to identify constructions in a similar way as the nonpredictability criterion, while simultaneously recasting the distinction in gradient rather than in categorical terms (see later in this section for a discussion of this gradient view).

These comments help explain the differences between Goldberg’s earlier accounts and her third and most recent definition of constructions, as stated in her 2019 monograph:

[C]onstructions are understood to be emergent clusters of lossy memory traces that are aligned within our high- (hyper!) dimensional conceptual space on the basis of shared form, function, and contextual dimensions.

As is evident from this quote, Goldberg’s latest definition completely does away with the notion of nonpredictability. Instead, the similarity among instances is used to group them together in “clusters” that correspond to constructions. Moreover, Goldberg couches her view of constructions in more psychological terms than in earlier definitions, relying on the concepts of “memory traces,” “emergent clusters,” “conceptual space,” and “lossiness.” The latter concept is borrowed from computer science and characterizes speakers’ memories as partially abstracted (“stripped-down”) versions of the original input. The strong psychological component of the definition can be related to theoretical and methodological trends in CxG, where more and more emphasis has been placed on the cognitive reality of constructions, rather than on their description alone, and in which psycho- and neurolinguistic paradigms have become ever more important sources of evidence (see e.g. Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2020).

While Reference GoldbergGoldberg’s (2019) definition is the outcome of several decades of constructionist theorizing, it surely will not mark the last attempt to come to terms with the concept of “constructions.” One obvious question raised by the definition, for example, is how much formal, functional or contextual information has to be shared by a group of instances (or memory traces) for them to be classified as a construction. Clearly, determining an adequate threshold for similarity is an important task for future empirical research (see also Section 4.3). Another striking feature of the 2019 definition is that it no longer makes reference to frequency as a necessary or sufficient criterion for construction status, in contrast to Reference GoldbergGoldberg’s 2006 account (see the earlier definition in this section). This omission is, in fact, intentional, as Reference GoldbergGoldberg (2019) identifies a problem with the earlier frequency criterion. According to the 2006 definition, a pattern is only recognized as a construction if speakers have witnessed it with sufficient frequency. The paradox that Reference GoldbergGoldberg (2019: 54) identifies is this: How can speakers accrue experience with a pattern if they only store it once they have already encountered it with sufficient frequency? In other words, if speakers do not retain individual instances of a new pattern, then each newly witnessed instance would seem to be the first of its kind, and speakers would never reach the frequency threshold required for forming a constructional representation. There is, in fact, ample evidence that speakers do store single instances of use, also called “exemplars” (Reference Abbot-Smith and BehrensAbbot-Smith & Behrens 2006; Reference AmbridgeAmbridge 2020; Reference BybeeBybee 2010). The latter are an important feature of the view of grammar as an emergent system (Reference HopperHopper 1987) that many cognitive linguists and Construction Grammarians subscribe to (e.g. Reference Ellis and Larsen-FreemanEllis & Larsen-Freeman 2006; Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2006; Reference MacWhinney, Dąbrowska and DivjakMacWhinney 2019).

Given these arguments, researchers are faced with a potential dilemma: On the one hand, if scholars maintain Reference GoldbergGoldberg’s (2006: 18) well-known claim that “it’s constructions all the way down,” that is, that speakers’ grammatical knowledge in toto consists of constructions, then they need to count a single stored exemplar of a new pattern as a construction. This would undermine the frequency criterion of the 2006 definition discussed earlier in this section and allow a potentially exploding number of constructions into the theory. If, on the other hand, scholars reserve the label “construction” for groups of stored exemplars that have grown sufficiently large, then they seem to give up the claim that grammatical knowledge consists of constructions only, and instead treat constructions as generalizations over more atomic units.

There are several ways to (potentially) resolve this problem. One rather radical approach would be to abandon the notion of constructions entirely and to reconceptualize linguistic knowledge in terms of a network of associations. Reference SchmidSchmid’s (2020) entrenchment-and-conventionalization model goes in this direction, although he retains the notion of construction (however, he abandons the idea of constructions as “nodes” in a network; see Reference Schmid and SchmidSchmid 2017a). A second approach would also be quite radical as it would abandon one of the major tenets of CxG: retaining the concept of construction as a heuristic device but dropping the idea that constructions are cognitively plausible entities. This would, however, entail the question of why the concept of constructions is needed in the first place. A third, and potentially the most promising, approach is to adopt a gradualist notion of constructionhood (see Reference UngererUngerer 2023) – an idea that is also implicit in Goldberg’s latest definition and Langacker’s entrenchment criterion, as discussed earlier in this section. On this view, construction status is not conceived of as a binary concept according to which a linguistic unit either counts as a construction or does not. Instead, this approach assumes a gradient scale of constructionhood, understood as the degree to which a pattern is mentally encoded. This view, of course, entails challenges of its own: For example, the question remains of how degrees of constructionhood can be measured and whether such quantification could be used to define a threshold that patterns have to cross to be included in the constructional inventory of a given analysis (see also Section 4.3). However, there are good arguments in favor of a reconceptualization of constructions in gradualist terms – for instance, diachronic studies show very clearly that the emergence of constructions is usually a gradual process (Reference HartmannHartmann 2021; Reference Traugott and TrousdaleTraugott & Trousdale 2013).

As this discussion has illustrated, the concept of “construction” has undergone a considerable evolution over the last thirty years, and yet researchers are still grappling with its definition and operationalization. The different definitions of the concept have important consequences for the question of which linguistic units can be regarded as constructions – including the question of whether words and morphemes should count as constructions, which is the issue to which we now turn.

2.3 The Lower Boundary: Words and Morphemes as Constructions?

As the preceding sections have shown, Construction Grammarians initially focused on the analysis of idiomatic phrasal constructions such as let alone, before extending their purview to more general clause-level patterns like the ditransitive construction. Subsequent research, however, has also applied CxG principles to the “lower” end of the grammatical system, that is, to the lexical and morphological level. One important question in this context is how far “down” the notion of construction extends: Does it include words or even morphemes? We will address this question in two steps, starting with (bound) morphemes and then discussing the status of lexical items. As we shall see, this topic is another example of a seemingly simple question that has given rise to a complex and still ongoing debate.

Starting with the morphological level, some authors have relatively straightforwardly assumed that morphemes are constructions (e.g. Reference Boas, Hoffmann and TrousdaleBoas 2013; Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2006). This seems to make intuitive sense for free morphemes that form monomorphemic words such as car or about. These units match the definitions of “construction” laid out in the previous section: They combine a linguistic form with a meaning, and they are not predictable from other similar items or from their component parts. The same argument has also been made for bound morphemes like pre- or -ing (Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2006: 5), which are traditionally regarded as carrying lexical or grammatical meaning. This is, however, where Reference BooijBooij (2010) disagrees: He argues that morphemes should not be regarded as constructions “because morphemes are not linguistic signs, i.e. independent pairings of form and meaning” (Reference BooijBooij 2010: 15). In his view, bound morphemes are not meaningful on their own but only when combined with other items, which is why they are best accounted for by frame-and-slot patterns such as [[X]A-ness]N (as in greatness). According to Booij, the latter templates are constructions, but the morphemes that occur in them are not.

Booij’s view is appealing, even though one might wonder whether there is really a fundamental difference between regarding bound morphemes as constructions while stipulating that they cannot occur without a base, and positing a morphological construction that combines the morpheme with its (underspecified) base. Perhaps some scholars intend the former option as a shorthand version of the latter: Reference CroftCroft (2001), for example, states that morphemes can be constructions (p. 25), but he simultaneously illustrates them with constructional frames like [NOUN-s] (p. 17). Another complication is that the “independence” of a unit (whether it is free or bound) is sometimes difficult to assert, and that the distinction between morphemes and free words may rather be a continuum (Reference HaspelmathHaspelmath 2011). This becomes particularly clear if we look at processes of grammaticalization in which affixes arise from lexical items, as in the development of English -dom (e.g. in kingdom) from Old English dom ‘judgment, doom’ (Reference Traugott and TrousdaleTraugott & Trousdale 2013: 170).

Moving on to the lexical level, there is also disagreement about whether words should count as constructions, even though the reasons for this debate are different. On one side of the discussion, some scholars defend a fairly radical version of the lexicon–syntax continuum (see Section 1), according to which words like apple are, in terms of their status as constructions, fundamentally the same as clause-level constructions like the ditransitive and differ from the latter only in their degree of abstraction (Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2022: 10). In contrast, other researchers (e.g. Reference Dąbrowska, Evans and PourcelDąbrowska 2009; Reference Diessel, Dąbrowska and DivjakDiessel 2015) have argued that simple words should not be regarded as constructions, while complex words such as armchair and forgetful should. This is not, however, because these authors do not perceive monomorphemic words as meaningful; rather, they advocate a narrower understanding of the term “construction,” restricting it to “grammatical patterns that involve at least two meaningful elements, e.g., two morphemes, words or phrases” (Reference DiesselDiessel 2019: 11). Meanwhile, on this view, both simple words and constructions (in the narrow sense) are subsumed under the concept of signs in their traditional Saussurean sense as pairings of form and meaning.Footnote 4 This understanding of “sign” therefore corresponds to other scholars’ use of “construction” in its wide sense – as a result, researchers who adopt the latter view (e.g. Reference BooijBooij 2010; Reference Traugott and TrousdaleTraugott & Trousdale 2013) often use both terms interchangeably.

The question of whether “sign” or “construction” should serve as the coverall term for the basic units of language may be partly a terminological issue. As Reference DiesselDiessel (2019: 11) notes, restricting the term “construction” to complex units echoes its use in traditional grammar (see also Reference LangackerLangacker 1987: 83–87). On the other hand, it could be argued that the label “Construction Grammar” implies a wide understanding of the concept, according to which it encompasses the entirety of speakers’ grammatical knowledge (in line with Reference GoldbergGoldberg’s [2006: 18] claim that “it’s constructions all the way down”; see Section 2.2). Terminology aside, however, the deeper underlying question is whether or not there is a fundamental distinction between simple and complex constructions (or, using the alternative terms, between lexical and constructional signs). Reference DiesselDiessel (2019: 11) argues that such a distinction is indeed crucial because “lexemes and constructions are learned and processed in very different ways.” According to his view (Reference DiesselDiessel 2019: 107–111), lexemes are characterized by the fact that they tap directly into speakers’ world knowledge and are embedded in rich semantic networks.Footnote 5 (Complex) constructions, on the other hand, do not tap directly into encyclopedic knowledge; rather, they provide speakers with “processing instructions” for how lexemes should be combined and interpreted together. Diessel’s view also draws support from neurolinguistic evidence suggesting that there are considerable differences in the processing of lexical items compared with units above the word level (Pulvermüller, Cappelle, & Shtyrov 2013).

Nevertheless, the distinction between lexemes and constructions is complicated by several factors. First, the central notion of complexity deserves closer attention. At first glance, a complex construction can be relatively easily defined as a pattern that is composed of multiple discernible units or constituents (comparable to the distinction between simplex and complex words; see e.g. Reference BooijBooij 2012: 7). One question, however, is which features of constructions are at issue: Does complexity concern their form or also their meaning? Reference Dąbrowska, Evans and PourcelDąbrowska (2009: 217), for example, taking a Langackerian Cognitive Grammar perspective, argues that relational words such as verbs qualify as constructions because they are complex at both the semantic and the phonological levels. This view rests on the assumption that the semantics of a verb include representations for the participants involved in the event or action encoded by the verb. For example, Dąbrowska suggests that the lexical representation of trudge contains representations for the walker and the setting, similar to the more abstract intransitive motion construction, which includes representations for the mover and the path.Footnote 6

Another challenge for the distinction between simple and complex linguistic units is that words differ in their degree of analyzability, as has been convincingly demonstrated in the psycholinguistic literature (Reference HayHay 2003; Reference Hay, Baayen, Booij and van MarleHay & Baayen 2002). This has ramifications not only for their production and processing but also for their phonetic realization (Reference Bell, Ben Hedia and PlagBell, Ben Hadia, & Plag 2021) and even for the occurrence of spelling variants (Reference Gahl and PlagGahl & Plag 2019). For instance, a word like discernment can be segmented more readily than a word like government (Reference HayHay 2003: 136). This can be explained by assuming that complex words lead a “double existence” as instances of a (morphological) construction on the one hand and as lexical items in their own right on the other. The same has been argued for phrasal idioms such as pull strings, which seem to be simultaneously analyzed into their component parts and processed holistically (Reference BybeeBybee 1998: 424–425). The fact that expressions can thus be perceived as simple and complex at the same time, and that they may vary in how strongly they lean toward one pole or the other, suggests that the distinction between lexemes and complex constructions may be more gradient than is sometimes assumed.

Summing up, there seem to be arguments both in favor of and against drawing a distinction between simple and complex signs, and consequently between a wide and a narrow use of the term “construction.” While this casts doubt on radical conceptions that do not assume any qualitative differences between lexical and grammatical (or syntactic) constructions, it does not invalidate the idea that lexicon and grammar form opposite ends of a continuum. Regarding the question of what counts as a construction, these findings also support the idea of reconceptualizing constructionhood as a gradient and dynamic notion that can accommodate a range of construction types that behave in potentially dissimilar ways.

2.4 Summary

In this section, we have given a brief historical overview of the evolution of constructionist approaches, focusing on the key concept of construction itself. We have reviewed several definitions of constructions, arguing for a gradient and dynamic notion of constructionhood that is also compatible with the most recent definition of constructions proposed by Reference GoldbergGoldberg (2019). We have also sketched out some ongoing controversies about what types of linguistic units should be seen as constructions. In particular, the jury is still out regarding the question of whether words and morphemes can be considered constructions.

An aspect that we have not yet addressed is to what extent the theoretical disagreements about the definition of constructions affect scholars’ daily research practice. In some cases, the practical ramifications for linguistic analyses may be arguably quite limited: For example, researchers can use similar constructionist principles to account for lexical and morphological processes without agreeing on the exact definitions of terms like “construction” and “sign.” This may also explain why constructionist scholars can have very compatible views of language and still continue to debate the exact nature of these key concepts.

3 From Sign-Based to Radical: “Flavors” of Construction Grammar

The present Element could have been called Construction Grammar. But as CxG has developed into a highly diverse field, it has become quite common to follow, for instance, Reference Goldberg, Hoffmann and TrousdaleGoldberg (2013) in speaking of “constructionist approaches.” It is, of course, not always possible to tell different approaches clearly apart, nor to allocate individual researchers to a specific constructionist framework. After all, CxG is a very dynamic field of research that takes a bottom-up rather than a top-down approach to language, which entails that many details concerning its theoretical foundations are continually in flux. Nevertheless, we can distinguish different types of CxG along some key parameters. Reference Ziem and LaschZiem and Lasch (2013), for example, propose a coarse-grained distinction between formal constructionist approaches, on the one hand, and cognitive, usage-based, and typologically oriented approaches, on the other. Among the formal approaches are Berkeley CxG (Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al. 1988), Sign-Based CxG (Reference Sag, Boas and SagSag 2012), Fluid CxG (Reference Steels and SteelsSteels 2011) and Embodied CxG (Reference Bergen, Chang, Östman and FriedBergen & Chang 2005).Footnote 7 Meanwhile, the main frameworks that fall into the other (less formal) group are Cognitive CxG (e.g. Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1995) and Radical CxG (Reference CroftCroft 2001).Footnote 8 We cannot give an extensive overview of each of those different approaches here – for more in-depth introductions to the individual frameworks, we refer the reader to the excellent summaries that already exist (see e.g. the contributions in Reference Hoffmann and TrousdaleHoffmann & Trousdale 2013 and the further references in Table 1 in Section 3.4). Instead, we will discuss some important commonalities and differences between the six above-mentioned approaches, focusing on three key areas: formalization, research foci and methods. We will address these aspects in turn, considering in particular the more recent developments that have taken place in each framework.

Table 1 Summary of similarities and differences among the six “flavors” of Construction Grammar

| Berkeley CxG | Sign-Based CxG | Fluid CxG | Embodied CxG | Cognitive CxG | Radical CxG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formalization | High degree of formalization, characterized by attribute value matrices (AVMs) and unification | Limited formalization with varying notations (e.g. boxes, brackets) | ||||

| Research foci | Grammatical description, both of idiomatic and “regular” constructions; focus on constructional form | Computational modeling of language comprehension and/or production; language learning and evolution; technological applications | Cognitive and typological dimensions of language use; usage-based orientation; focus on constructional meaning; language change and acquisition | |||

| Methods | Introspective analysis; some empirical (corpus-based) work; constructicography | Introspective analysis; computational modeling (using customized software); psycholinguistic and neurolinguistic evidence | Introspective analysis; extensive corpus-based work; experimental methods | Introspective analysis; (largely qualitative) cross-linguistic comparisons | ||

| Core references | Reference Fillmore, Hoffmann and TrousdaleFillmore (2013); Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al. (1988); Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and ÖstmanFried and Östman (2004) | Reference Boas and SagBoas and Sag (2012); Reference Michaelis, Hoffmann and TrousdaleMichaelis (2013, Reference Michaelis, Heine and Narrog2015) | Reference Steels and SteelsSteels (2011, Reference Steels, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013, Reference Steels2017); Reference Van Trijp, Beuls and Van EeckeVan Trijp et al. (2022) | Reference Bergen, Chang, Östman and FriedBergen and Chang (2005, Reference Bergen, Chang, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013); Reference Feldman, Dodge, Bryant, Heine and NarrogFeldman, Dodge, and Bryant (2015); Reference FeldmanFeldman (2020) | Reference Boas, Hoffmann and TrousdaleBoas (2013); Reference GoldbergGoldberg (1995, Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2019); Reference HilpertHilpert (2019) | Reference CroftCroft (2001, Reference Croft, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013, Reference Croft2020) |

3.1 Formalization

Even though all constructionist approaches employ some degree of formalization, a rough distinction can be drawn between approaches that use more elaborate and strictly defined formal conventions and those that do not. As mentioned at the beginning of Section 3, Berkeley, Sign-Based, Fluid, and Embodied CxG can be counted among the more formal frameworks, while Cognitive and Radical CxG constitute less formal variants.

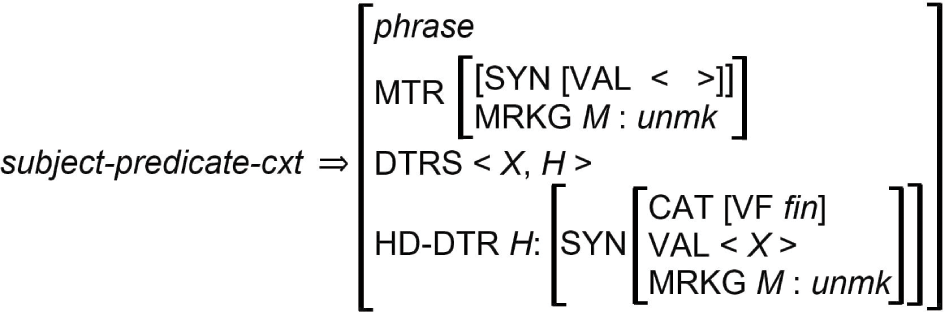

The formal Construction Grammars share two important characteristics. First, they represent constructions in the form of feature structures, and more specifically as attribute-value matrices (AVMs). Each construction is characterized by a number of syntactic attributes, for example syntactic category and valence, and semantic attributes, such as reference and thematic roles; each of these attributes is assigned a unique value. This is illustrated in Figure 1 with a Sign-Based CxG analysis of the subject–predicate construction, which licenses basic declarative clauses (Reference Michaelis, Hoffmann and TrousdaleMichaelis 2013). As the diagram shows, the construction specifies two daughters that combine into a mother node. The head daughter H, in this case the verb, is defined by several syntactic features: its category (finite verb), its valents (the other daughter X, here the subject), and its marking (i.e. the absence of a grammatical marker such as the complementizer that). The mother node is similarly unmarked, and has an empty valence list because it selects no further arguments. Naturally, specific frameworks vary somewhat in terms of the attributes they use and how flexibly they handle them. Especially the computationally oriented approaches, Fluid CxG and Embodied CxG, tend to be relatively agnostic regarding what specific features should be included in the representations, as long as they improve the performance of the models (Reference SteelsSteels 2017: 188).

Figure 1 Sign-Based CxG formalism: a feature-based analysis of the subject–predicate construction

The second hallmark of formal Construction Grammars concerns the specific mechanism they use to combine feature structures: unification. This operation has played a long-standing role in constraint-based theories such as Reference Gazdar, Klein, Pullum and SagGazdar et al.’s (1985) Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar (GPSG) and Reference Pollard and SagPollard and Sag’s (1987) Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG), both of which heavily inspired Sign-Based CxG (see Reference Michaelis, Heine and NarrogMichaelis 2015: 151). Unification is defined as an operation by which two structures that have matching feature values combine into a new structure that “contains no more and no less than what is contained in its component AVMs” (Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and ÖstmanFried & Östman 2004: 33; see also Reference ShieberShieber 1986). For example, returning to the example in Figure 1, the verb unifies with an argument that matches its valence specification in order to form a subject–predicate phrase.

In contrast to the aforementioned approaches, the less formal Construction Grammars – Cognitive CxG and Radical CxG – use neither AVM-style feature structures nor unification. The lack of formalism in these approaches is intentional, as Reference Goldberg, Hoffmann and TrousdaleGoldberg (2013: 29) highlights: “I have avoided using all but the most minimal formalization in my own work because I believe the necessary use of features that formalism requires misleads researchers into believing that there might be a finite list of features or that many or most of the features are valid in cross-linguistic work. The facts belie this implication.”

Reference GoldbergGoldberg (2006: 216–217) provides several further arguments against the use of AVMs for representing constructions. For example, she remarks that formalist approaches often do not account for the rich frame semantics of constructions and instead describe their semantic features in terms of simple “constants.” Moreover, she argues that formal analyses tend to overemphasize syntactic features over semantic ones, and that the formalisms are usually too unwieldy to capture the amount and complexity of speakers’ constructional knowledge. Finally, the aforementioned quote from Reference Goldberg, Hoffmann and TrousdaleGoldberg (2013) also questions the typological validity of the features used in formal approaches, a theme that is particularly prominent in Croft’s Radical CxG. Reference CroftCroft (2001, Reference Croft2020) argues against the universality of grammatical categories such as word classes (e.g. noun, adjective) and syntactic relations (e.g. subject, object). Based on evidence from typologically distant languages, he shows that both the syntactic environments that define word classes and the linking mechanisms between verbs and their arguments vary considerably across languages. As a result, he suggests that word classes are characterized by language-specific constructions and that syntactic relations can be derived from underlying semantic relations (again, in construction-specific ways).

It is debatable whether Goldberg’s and Croft’s criticisms – also considering that some of them were stated a while ago – still paint an accurate picture of formal Construction Grammars, and if so, how the problems they identify could be resolved. For one, some of the authors’ remarks have been accommodated by the formal approaches: Features, for example, can have complex values, so the semantic attributes of AVMs can be filled by rich semantic frames, a practice that has been adopted in recent formal work (Reference Sag, Boas and SagSag 2012; Reference SteelsSteels 2017). It also seems feasible that the features posited by these frameworks could be defined in language-specific ways rather than via universal primitives, thus accounting for typological variability in their realization (see e.g. Reference Fried, Östman, Fried and ÖstmanFried & Östman 2004: 77).

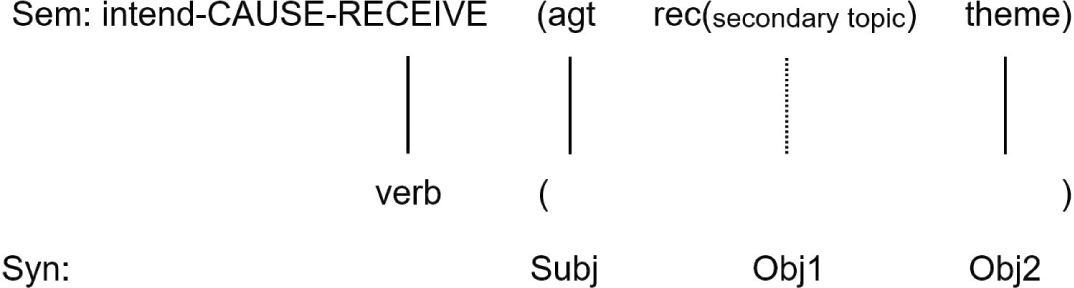

Another question is whether the less formal varieties of CxG deal more successfully with the challenges identified by Goldberg and Croft. While nonformal Construction Grammars typically do not rely on elaborate feature structures, they nevertheless characterize constructions in terms of their salient properties. Compare Figure 2, which reproduces a Cognitive CxG analysis of the ditransitive construction (Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2006; see Section 2.2 for examples). The upper half of the diagram outlines the semantic properties of the construction (its overall meaning and the thematic roles it comprises), while the lower half specifies its syntactic functions. Other researchers working in nonformal Construction Grammars have used even more abbreviated representations, such as the bracketed notation in (8). Nevertheless, both these representations comprise the same features that could also be listed as part of an AVM (e.g. as a valence list or within a semantic frame). It is also worth noting that Figure 2 makes use of the same grammatical categories (e.g. syntactic functions) that Croft (2000, 2021) criticizes for their lack of crosslinguistic validity. While these categories may not be crosslinguistically stable, it appears that, for the purposes of a language-specific analysis, they provide a useful and ultimately indispensable way of capturing generalizations.

(8) [[SUBJ V OBJ1 OBJ2] ↔ [X CAUSE Y to RECEIVE Z]] (Reference Traugott and TrousdaleTraugott & Trousdale 2013: 59)

Figure 2 Cognitive CxG analysis of the ditransitive construction

All things considered, there may be no principled reasons why Construction Grammars should or should not rely on a certain degree of formalization. Rather, it seems that the differences between frameworks are largely a result of their specific research goals (which will be discussed in more detail in the next section). For example, a primary goal of Sign-Based CxG and related formal approaches is to account for “the licensing of word strings by rules of syntactic and semantic composition” (Reference Michaelis, Heine and NarrogMichaelis 2015: 151) – an enterprise that these frameworks share with traditional generative grammar. For this purpose, it seems feasible to employ a rigorous unification-based formalism that captures how well-formed structures arise from feature matching among their component parts. Moreover, unification lends itself to computational implementation (Reference KnightKnight 1989); and the algorithms are not affected by how detailed and potentially “unwieldy” the AVMs are. For the less formal Construction Grammars, on the other hand, the readability of the representations is an important consideration, and researchers tend to highlight only those features of constructions that are relevant for their respective analyses. For the purposes of the latter – which focus on the mental representation of constructions and their use in naturalistic speech – the use of precise formalisms may thus be less important.

3.2 Research Foci

As hinted at in Section 3.1, the different “flavors” of CxG are not only distinguished by their degree of formalization, but they also differ in terms of the research questions they tend to emphasize. Broadly, three subgroups can be distinguished in this context, characterized by their respective focus on (i) grammatical description; (ii) computational modeling; or (iii) the cognitive and typological dimensions of language use.

Starting with the first group, Berkeley CxG and its successor framework, Sign-Based CxG, have primarily been concerned with providing detailed descriptions of grammatical phenomena, using the formal tools discussed in the previous section. As outlined in Section 2.1, the early work by the Berkeley group focused particularly on analyses of partially filled idioms, such as let alone (Reference Fillmore, Kay and O’ConnorFillmore et al. 1988) and the What’s X doing Y? construction (Reference Kay and FillmoreKay & Fillmore 1999). This interest was soon extended to constructions in other languages that carry specific syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic properties, such as right-detached comme in French, as in C’est cher, comme appareil, ça ‘That’s an expensive camera’ (Reference Lambrecht, Fried and ÖstmanLambrecht 2004). Moreover, proponents of the framework have also investigated more general, nonidiomatic phenomena, such as extraposition (Reference Michaelis and LambrechtMichaelis & Lambrecht 1996) and different verb-complementation patterns (Reference Fillmore, Hoffmann and TrousdaleFillmore 2013).

This line of research has been carried on by Sign-Based CxG, which was partially developed by proponents of the earlier Berkeley approach. In his detailed overview of the paradigm, Reference Sag, Boas and SagSag (2012) provides Sign-Based analyses of a broad range of construction types, including lexical classes (e.g. the main verb construction), inflectional morphology (e.g. the preterite construction), phrasal structure (e.g. the head-complement construction), and argument structure (e.g. the ditransitive). It has been suggested that Sign-Based CxG tends to focus more on the formal-syntactic rather than the semantic aspects of constructions (e.g. Reference FeldmanFeldman 2020: 151). For example, to account for filler-gap phenomena such as wh-interrogatives and topicalization, Reference SagSag (2010) posits an overarching construction that only has formal specifications but no meaning. This contrasts with other views, primarily by proponents of Cognitive CxG, who have called the existence of meaningless schemas into question, arguing instead that every construction must have a meaning, even if only a highly abstract one (Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2006: 166–182; Reference HilpertHilpert 2019: 50–74; Reference DiesselSommerer and Baumann 2021: 125–126).

Moving on to the second group of theories that share an overall research goal, Fluid CxG and Embodied CxG aim primarily at constructing computational models of language processing. As a result, the two frameworks focus particularly on the practical challenges involved in creating functional CxG implementations. Still, the two approaches differ somewhat in terms of their backgrounds and research foci. Fluid CxG has been under development at computer science labs in Paris and Brussels since the late 1990s. Its main goal is to create a construction-based architecture for language production and comprehension (Reference SteelsSteels 2017). In doing so, the proponents of the framework “do not make any claims about biological realism or cognitive relevance” (Reference SteelsSteels 2017: 181), focusing instead on maximizing the descriptive coverage of their models. Recent analyses have addressed a range of constructions, including English auxiliaries (Reference Van TrijpVan Trijp 2017) and long-distance dependencies (Reference Van TrijpVan Trijp 2014), Dutch word order (Reference Van EeckeVan Eecke 2017), and Spanish verb conjugation (Reference BeulsBeuls 2017). Moreover, the approach has been used to model aspects of language evolution (Reference SteelsSteels 2012; Reference Steels and SzathmárySteels & Szathmáry 2016). In parallel to these research contributions, Fluid CxG has generated a number of real-world applications, among them a model for visual question answering (i.e. answering text questions about images; Reference Nevens, Eecke and BeulsNevens, Eecke, & Beuls 2019) and a platform for analyzing opinions on social media (Reference Willaert, Van Eecke, Beuls and SteelsWillaert et al. 2020).

Embodied CxG, on the other hand, developed out of the Neural Theory of Language project (Reference FeldmanFeldman 2006) at the University of California, Berkeley. As a result, its proponents aim to model speakers’ grammatical processing specifically in relation to its neural underpinnings. In contrast to the other formally oriented Construction Grammars, Embodied CxG emphasizes the analysis of meaning, and of embodied meaning in particular (Reference FeldmanFeldman 2020: 151). As Reference Bergen, Chang, Hoffmann and TrousdaleBergen and Chang (2013) outline, the framework aims to account for the role of embodied simulation in language processing, that is, speakers’ tendency to activate perceptual and motor systems in the brain that recreate experiences similar to the ones that arise during actual perception or movement (Reference BarsalouBarsalou 1999). Previous studies have used Embodied CxG to analyze phenomena such as the English caused-motion construction (Reference Dodge, Petruck, Artzi, Kwiatkowski and BerantDodge & Petruck 2014) and Hebrew verbal morphology (Reference Ungerer and HartmannSchneider 2010), and to model aspects of grammatical parsing (Reference BryantBryant 2008) and acquisition (Reference MokMok 2009). Recent work, meanwhile, has somewhat moved away from linguistic analysis and instead focused on technological applications in natural language understanding, including verbal control of robots (Reference Eppe, Trott, Raghuram, Feldman, Janin, Benzmüller, Sutcliffe and RojasEppe et al. 2016) and a system for providing health advice (Reference FeldmanFeldman 2020).

Finally, as a third group that is characterized by similar research goals, Cognitive CxG and Radical CxG focus on the cognitive, typological, and contextual factors that underlie and shape speakers’ grammatical knowledge. In contrast to the above-mentioned frameworks, these approaches identify themselves as “usage-based” (see e.g. Reference Barlow and KemmerBarlow & Kemmer 2000; Reference Langacker and Rudzka-OstynLangacker 1988; Reference TomaselloTomasello 2003), devoting their attention to how “experience with language creates and impacts the cognitive representations for language” (Reference Bybee, Hoffmann and TrousdaleBybee 2013: 49). As a result, the frameworks are sometimes grouped under the broader label of “Usage-Based CxG” (e.g. Reference Diessel, Dąbrowska and DivjakDiessel 2015).Footnote 9 Compared with the other approaches discussed above, proponents of usage-based Construction Grammars tend to focus less on the form side of constructions and more on characterizing their rich meanings in psychologically plausible ways, using concepts such as construal (Reference Langacker, Dąbrowska and DivjakLangacker 2019), conceptual blending (Reference Turner, Dąbrowska and DivjakTurner 2019), and semantic maps for cross-linguistic comparisons (Reference CroftCroft 2022).

Despite their similarities, Cognitive and Radical CxG also differ in terms of their research questions. Proponents of Cognitive CxG are particularly concerned with how constructions motivate each other in virtue of their mutual similarities and associative relations (Reference Booij, Gisborne and HippisleyBooij 2017; Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1995; Reference LakoffLakoff 1987), a notion that is captured by positing networks of constructions (see Section 4 for a detailed discussion). In addition, they often study how speakers’ linguistic behavior is shaped by domain-general cognitive processes such as attention, categorization, analogy, and social cognition (e.g. Reference Bybee, Hoffmann and TrousdaleBybee 2013; Reference DiesselDiessel 2019; Reference GoldbergGoldberg 2019). As what is probably the largest strand of CxG to date, Cognitive CxG has spawned an extensive body of work. While the paradigm became initially known particularly for its analyses of argument-structure constructions (e.g. Reference BoasBoas 2003; Reference GoldbergGoldberg 1995; Reference PerekPerek 2015), its proponents have since tackled a wide range of other phenomena, including (but not limited to) complex clauses (Reference HoffmannHoffmann 2011), information structure (Reference Goldberg, Östman and FriedGoldberg 2005), discourse organization (Reference TraugottTraugott 2022), tense and modality (Reference BergsBergs 2010; Reference Cappelle and DepraetereCappelle & Depraetere 2016), and phrase-internal structure (Reference SommererSommerer 2018), as well as inflectional and derivational morphology (Reference BooijBooij 2010). The framework is also often extended to diachrony, with many proponents of “Diachronic Construction Grammar” (Reference Coussé, Andersson and OlofssonCoussé, Andersson, & Olofsson 2018; Reference Ungerer and HartmannSommerer & Smirnova 2020; Reference Traugott and TrousdaleTraugott & Trousdale 2013) situating their work broadly within Goldbergian usage-based CxG (see Section 4.1 for an explanation of key diachronic concepts such as “constructionalization”). Moreover, there has been considerable research on language acquisition, focusing in particular on children’s early item-based constructions (e.g. ___ gone, as in Cherry gone; Reference TomaselloTomasello 1992), the emergence of abstract constructions, and the acquisition of complex sentences (for overviews, see Reference BehrensBehrens 2021; Reference Diessel, Hoffmann and TrousdaleDiessel 2013; Reference TomaselloTomasello 2003).

Radical CxG, on the other hand, relies on a smaller body of work, most of it created by William Croft (e.g. Reference Croft2001; Reference Croft2020). The framework has a strong typological focus, centering on the question of which aspects of speakers’ grammatical knowledge are language- and construction-specific, and which ones may be universal. In his work, Croft discusses many grammatical core phenomena, including word classes, argument structure, syntactic roles, and grammatical categories like voice, aspect, and tense. Further applications have extended the framework to aspects of grammar acquisition (Reference Deuchar and VihmanDeuchar and Vihman 2005) and template-based phonology (Reference Vihman and CroftVihman & Croft 2007) as well as modal and discourse particles (Reference Fischer, Alm, Degand, Cornillie and PietrandreaFischer & Alm 2013).

3.3 Methods

Across the different constructionist approaches, there is a broad consensus that in order to understand the nature and use of constructions, we need evidence from a wide variety of sources – more technically, we have to triangulate evidence from different methodological approaches (Reference Baker and EgbertBaker & Egbert 2016). Still, we can draw some broad generalizations in terms of which methods the different approaches are most closely connected to.

First, it should be acknowledged that all types of CxG rely to some extent on the “introspective” method, that is, researchers’ use of their own intuitive judgments to analyze selected examples and develop theoretical accounts (but see Reference WillemsWillems 2012 for potential differences between introspection and intuition). Introspection plays a crucial role in all theoretical and descriptive approaches to grammar: As Reference Janda and JandaJanda (2013: 6) points out, “[i]ntrospection is irreplaceable in the descriptive documentation of language” (see also Reference Talmy, Gonzales-Marquez, Mittelberg, Coulson and SpiveyTalmy 2007). While many Construction Grammarians, especially proponents of the more usage-based varieties, are skeptical of introspection, perceiving it perhaps as a hallmark of more traditional (generative) analyses (Reference WillemsWillems 2012: 665), the method nevertheless serves an important role in hypothesis generation, theory building, and the interpretation of results.

Beyond that, most Construction Grammarians agree that introspection needs to be combined with other sources of evidence, but specific approaches differ in terms of what methods they use and the extent to which they apply them. Naturally, the choice of methods is closely related to the research goals of the different frameworks. As such, Berkeley and Sign-Based CxG tend to rely relatively strongly on fine-grained theoretical analyses, in line with their goal of providing a formally rigorous account of the grammatical system. Nevertheless, work in these areas has also been partially assisted by corpus methods – see, for example, Reference Brenier and MichaelisBrenier and Michaelis (2005) for a corpus-based study of copula doubling in the context of formal CxG.

Especially Cognitive CxG has developed a broad inventory of empirical methods to study the synchronic and diachronic use of constructions and draw inferences about their representation in speakers’ minds. In particular, proponents of the framework draw on an ever-expanding set of corpus-based methods. These approaches are guided by the usage-based assumption that linguistic knowledge is experience-based: Children learn language by detecting patterns in the input they receive, thus building up a dynamic network of constructions that is subject to lifelong reorganization (Reference Ambridge and LievenAmbridge & Lieven 2011; Reference TaylorTaylor 2012; Reference TomaselloTomasello 2003). In line with this, constructionist corpus analyses aim at gauging language users’ linguistic knowledge on the basis of frequency and distribution data from authentic usage. They draw primarily on measures of frequency, dispersion, and association (Reference DivjakDivjak 2019; Reference GriesGries 2008), distributional semantic methods (Reference PerekHilpert & Perek 2015; Reference DiesselPerek 2016), and (most recently) artificial neural networks (Reference BudtsBudts 2022; Reference Budts, Petré, Sommerer and SmirnovaBudts & Petré 2020).

One particularly widespread corpus-based method in constructionist work is collostructional analysis (Reference Gries and StefanowitschGries & Stefanowitsch 2004; Reference Ungerer and HartmannStefanowitsch & Gries 2003, Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2005). Following a long tradition of corpus-linguistic approaches that investigate collocations, that is, words that occur together, collostructional analysis focuses on the interaction between words and constructions. Consider, for instance, the into-causative construction, as in They talked us into writing this Element: Using the simplest version of collostructional analysis, simple collexeme analysis, Reference Ungerer and HartmannStefanowitsch and Gries (2003: 225) show that words like trick, fool, and coerce occur at above-chance level in the first verb slot of this construction, when compared to their total corpus frequency. Using covarying collexeme analysis, which focuses on the co-occurrence of items in a construction with two open slots, Reference Stefanowitsch and GriesStefanowitsch and Gries (2005: 13) furthermore show that fool and thinking are most likely to occur together in the construction, while other verb pairs like force into thinking or provoke into accepting are much less likely to co-occur. Importantly, collostructional techniques are also subject to constant refinement, as their methodological rationale and cognitive underpinnings have been controversially, and sometimes heatedly, debated (Reference GriesGries 2015; Reference Küchenhoff and SchmidKüchenhoff & Schmid 2015; Reference DiesselSchmid & Küchenhoff 2013).

These corpus approaches have come to be increasingly complemented by experimental paradigms, which are used especially by proponents of Cognitive CxG but also inform research in other frameworks such as Fluid and Embodied CxG (e.g. Reference Bergen, Gonzalez-Marquez, Mittelberg, Coulson and SpiveyBergen 2007; Reference FeldmanFeldman 2006). Commonly used methods include acceptability judgments (Reference DąbrowskaDąbrowska 2008; Reference Gries and WulffGries & Wulff 2009), sorting tasks (Reference Bencini and GoldbergBencini & Goldberg 2000; Reference PerekPerek 2012), artificial language learning (Reference Casenhiser and GoldbergCasenhiser & Goldberg 2005; Reference Ungerer and HartmannPerek & Goldberg 2015), priming (Reference Busso, Perek and LenciBusso, Perek, & Lenci, 2021; Reference UngererUngerer 2021, Reference Ungerer2022), and a number of other techniques, such as sentence repetition (Reference Diessel and TomaselloDiessel & Tomasello 2005) and sentence completion (Reference PerekPerek 2015). Experimental approaches are needed because many aspects related to the processing, storage, and acquisition of constructions cannot be satisfactorily answered on the basis of corpus data alone. Among other things, experimental studies have lent support to the cognitive reality of “constructions” as meaningful elements of speakers’ linguistic knowledge. Reference Bencini and GoldbergBencini and Goldberg (2000), for example, presented speakers with a list of sentences that differed either in terms of the verb they contained or the construction they instantiated, and asked participants to sort the sentences into categories. Interestingly, the authors found that participants were more likely to group instances of the same construction into a category than sentences with the same verb. This suggests that constructions are psychologically real units that play an important role for the way speakers categorize the linguistic input.

Meanwhile, artificial language-learning experiments can shed light on how the input shapes speakers’ acquisition of new constructions. In Reference Ungerer and HartmannPerek and Goldberg’s (2015) study, for example, participants were exposed to made-up verbs (e.g. moop) that occurred in novel constructions (featuring non-English word orders). Depending on whether the verbs combined with different constructions or always with the same construction during the training phase, participants used them either more “liberally” or more “conservatively” in a subsequent productive task, suggesting that the input determined what constructional generalizations speakers formed. Finally, priming studies are particularly informative about relations between constructions in speakers’ mental networks. This follows from the assumption that the degree to which one construction primes, that is, affects the processing of, another construction functions as an indicator of how similar speakers’ representations of the two patterns are (Reference UngererUngerer 2022; see Section 4.1 for details).

While constructionist research has thus drawn on a variety of experimental methods, the paradigm could further benefit from other techniques used in the wider context of cognitive linguistics, especially in experimental semantics (Reference Matlock, Winter, Heine and NarrogMatlock & Winter 2015) and experimental semiotics (Reference Nölle, Galantucci, García and IbáñezNölle & Galantucci 2023). Research in the former field, which investigates the meaning not only of individual words but also of constructions, has obvious implications for constructionist work. For example, using a mouse-tracking paradigm, Reference Anderson, Matlock and SpiveyAnderson, Matlock, and Spivery (2013) found interesting differences between sentences with varying aspectual construal (progressive vs. nonprogressive), thus supporting the cognitive-linguistic hypothesis that distinct grammatical constructions yield differences in semantic construal. Experimental semiotics, meanwhile, addresses the question of how symbolic systems come about by conducting laboratory studies that involve novel communication systems. For instance, Reference Goldin-Meadow, So, Ozyurek and MylanderGoldin-Meadow et al. (2008) and Reference Christensen, Fusaroli and TylénChristensen, Fusaroli and Tylén (2016) used silent-gesture paradigms to account for the emergence and cognitive underpinnings of cross-linguistically well-attested word-order preferences. Especially for usage-based CxG, which sees language as a highly dynamic system, the results of these studies are particularly relevant because they can help explain common pathways of language change and grammaticalization (or “constructionalization”; see Section 4.1).

Returning to other methods used in CxG, constructionist work in the Berkeley tradition has given rise to a research strand that we have not addressed so far and which uses lexicographic methods to build large-scale repositories of constructions. Researchers working in this area, which has become known as “constructicography” (Reference Lyngfelt, Borin, Ohara and TorrentLyngfelt et al. 2018), create construction entries that are then linked up with semantic frames from FrameNet (Reference Fillmore, Lee-Goldman, Rhomieux, Boas and SagFillmore et al. 2012). A semantic frame is here defined as “any system of concepts related in such a way that to understand any one concept it is necessary to understand the entire system” (Reference Petruck, Verschueren and ÖstmanPetruck 2022: 592). Constructional inventories, or “construct-i-cons” (see Section 4), are currently being built for several languages, including English (Reference Perek and PattenPerek & Patten 2019), German (Reference Ziem, Flick and SandkühlerZiem, Flick, & Sandkühler 2019), Russian (Reference Janda, Lyashevskaya, Nesset, Rakhilina, Typers, Lyngfelt, Borin, Ohara and TorrentJanda et al. 2018), and Brazilian Portuguese (Reference Torrent, da Silva Matos, Lage, Lyngfelt, Borin, Ohara and TorrentTorrent et al. 2018). While such constructional inventories can form the basis for cross-linguistic comparisons, the strand of CxG that has most strongly focused on comparative methods is arguably Radical CxG. Notably, proponents of this paradigm often rely on qualitative analyses rather than quantitative tools (but see e.g. Reference Deuchar and VihmanDeuchar & Vihman 2005 for quantitative case studies of language acquisition from a Radical CxG perspective).

Finally, the methods discussed so far are complemented by computational approaches, which are used in particular by Fluid and Embodied CxG to model aspects of language comprehension and/or production. Fluid CxG provides what is arguably the most advanced computational implementation of CxG to date. The use of this formalism has been recently facilitated by the release of the FCG Editor (Reference Van Trijp, Beuls and Van EeckeVan Trijp, Beuls, & Van Eecke 2022), an open-source development tool with which researchers can customize their own grammars for sentence parsing and production. Proponents of Fluid CxG have also created models of language learning and evolution using autonomous robots that play language games (Reference Steels and HildSteels & Hild 2012). Embodied CxG, meanwhile, has developed its own development platform, the ECG workbench (Reference Eppe, Trott, Raghuram, Feldman, Janin, Benzmüller, Sutcliffe and RojasEppe et al. 2016), even though the latter seems to have more limited functionality than its Fluid CxG counterpart (Reference Van Trijp, Beuls and Van EeckeVan Trijp et al. 2022: 6–7).

3.4 Summary