Stories of Oduduwa’s arrival at Ile-Ife, and his children’s subsequent migration into new territories (Atanda Reference Atanda1980:2; Johnson Reference Johnson1921), mark the beginning of Yoruba history studies, from Ajayi Crowther and Samuel Johnson onwards. One origin legend, claiming that the Yoruba had inhabited their territory from time immemorial, begins with Olodumare (God) sending Oduduwa from heaven to create the solid earth and the human race (Atanda Reference Atanda1980:1–2). In the legend, Oduduwa descends to earth on a long chain and lands at Ile-Ife, where he establishes solid ground and plants the first seed (Akintoye Reference Akintoye, Lawal, Sadiku and Dopamu2004:4–5). This tradition establishes Ile-Ife as the cradle of the Yoruba, and Oduduwa as the Yoruba’s progenitor, or first ancestor. Oduduwa was considered the founder of the first Yoruba kingdom, situated in Ile-Ife, beginning the Yoruba kingship.

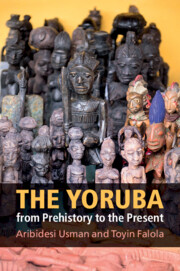

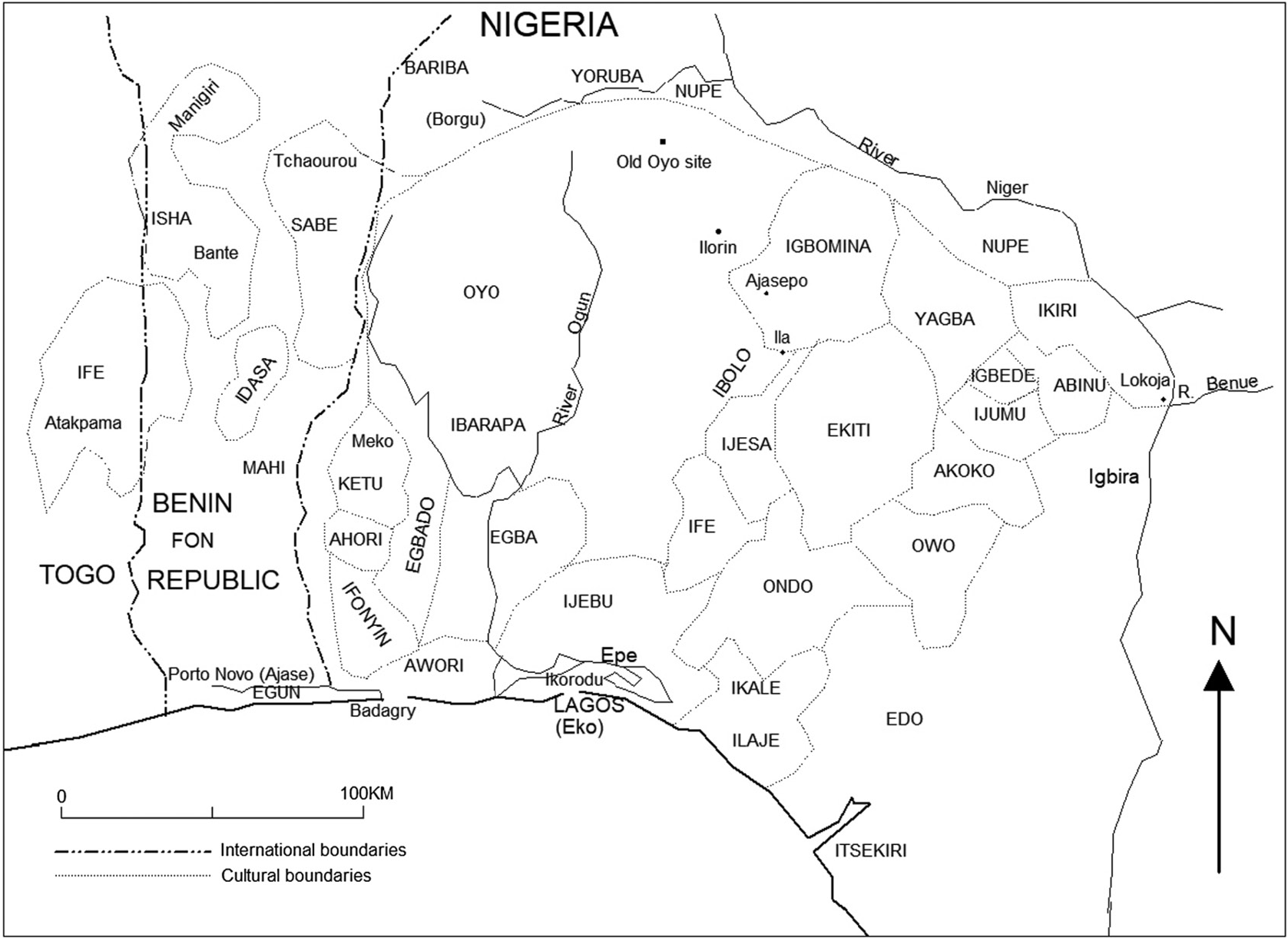

Another version of the origin myth, detailing later developments, claims that Oduduwa led the Yoruba to their present location after migrating from the east. The story claims that the migration was caused by political disturbances accompanying the expansion of Islam (Atanda Reference Atanda1980), but the exact location of the legend’s “east” is not definite. A third claim, divergent from the above traditions, asserts that Ile-Ife was already inhabited when Oduduwa arrived. This introduces the story of Agbonmiregun, whom Oduduwa met at Ile-Ife (Atanda Reference Atanda1980). Despite their differences, these accounts all feature Oduduwa as the main character (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Yoruba culture area

Early archaeological work at Ile-Ife and its immediate environs tended to support the theory of indigenous origin. Excavated material indicated a wealthy, sophisticated society with an established monarchy (Willett Reference Willett1967). Radiocarbon dating places the “classical” period of Ife art at about AD 1000–1400, which is also the period covered by the king-lists of large polities like Oyo, Ketu, Benin, and Ijebu (Eades Reference Eades1980). Many of these polities were established between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries (Smith Reference Smith1969), with the founders claiming to have migrated from Ile-Ife at some point (Eades Reference Eades1980).

Increasing archaeological and linguistic evidence has fueled growing skepticism about some of the origin claims from Yoruba oral traditions. Archaeological work carried out in the last century at Iwo Eleru, near Akure in eastern Yorubaland and at Iffe-Ijumu in northern Yorubaland, points to the presence of Late Stone Age human settlements in Yorubaland as early as 9000 BC (Oyelaran Reference Oyelaran1991, Reference Oyelaran1998; Shaw Reference Shaw and Megaw1980a). This indicates that people have lived for millennia in the area that would become the Yoruba region.

Linguistic evidence has weakened the theory of Oduduwa’s migration from Mecca or the Nile Valley. Adetugbo (Reference Adetugbo and Biobaku1973:203) has argued that the genetic similarities between the Yoruba language and other Kwa-family language groups such as Edo, Igala, Nupe, Igbo, Idoma, Ijo, Efik, Fon, Ga, and Twi mean that the speakers of these languages must have shared a common origin. Considering the time needed for differentiation to occur among these languages, the speakers must have had a close relationship in prehistoric times. Using their resemblance and the similar designations for local plants and animals, Adetugbo asserts that these languages were acquired by the Yoruba within tropical Africa, not outside the region. This undermines theories of migration that trace the original home of the Yoruba to the Middle East or North Africa.

Scholars have examined Yoruba settlement centers outside Ile-Ife, in other parts of Yorubaland. In the Ado kingdom in Ekiti, Ilesun is regarded as the oldest habitation in the area, and the Elesun, ruler of Ilesun, is still highly revered. According to traditions, the people of Ilesun never came from elsewhere, emerging at the foot of the Olota Rock (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:14). Some legends suggest that the Ilesun people were later joined by other settlements from the nearby forests, who came to enjoy the protection of the spirit of the Olota Rock (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). In the Owo kingdom, in the southeastern forests, Idasin was the earliest settlement in the area (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:15). Alale was the ruler of Idasin and high priest of the Ogho spirit, the protector of the area, using his power over other settlements that came after Idasin (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). Oba Ile, near Akure, is recognized in oral tradition as the oldest settlement in the Yoruba region (Atanda Reference Atanda1980:3). Oba Ile was revered and feared by the surrounding settlements because it possessed the shrine of the strongest ancient spirits inhabiting the depths of the earth (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:15).

The Yoruba language of the northeast, in the Okun subgroup’s area, presents greater internal diversity in its dialects than other Yoruba areas (Obayemi Reference Obayemi and Ikime1980:148). This supports the theory that the “area of the greatest linguistic diversity is significant for determining the source of population dispersal” (Oyelaran Reference Oyelaran1998:67). Because of this diversity, Obayemi (Reference Obayemi and Ikime1980:148) asserted that northeast Yorubaland’s present population is indigenous to the area; they are not migrants from Ile-Ife or Oyo. Similarly, oral traditions from Igbomina suggest early settlements that correspond with the Ile-Ife period. A tradition of Ọbà-Isin claimed that the generic oriki (cognomen) of the Ọba people, “ọmọ ẹrẹ,” meaning “offspring of the mud,” describes the possibility of autochthonous origin (Aleru Reference Aleru1998; Raji Reference Raji1997:44). Yoruba settlements existed outside Ile-Ife either before, or simultaneously with, the advent of Oduduwa. This suggests a period of Yoruba history before Oduduwa – a period about which much is still unknown.

Historians and other scholars today focus less on the origins and careers of Oduduwa’s sons, focusing more on the region’s general development of social and political complexity. Linguistic and archaeological evidence suggests that social and cultural differentiation had occurred before the period described in the present ruling dynasties’ origin myths (Obayemi Reference Obayemi, Ajayi and Crowder1976:201).

In the beginning, it appears there was no general name for the Yoruba as a whole. People referred to themselves by the name of their subgroup, particular settlement, or geographic area – the Yoruba-speaking groups in the Republic of Benin and Togo still address themselves as “Ife” rather than as “Yoruba” (Eades Reference Eades1980:4). The name “Yoruba” was originally given to the Oyo people by the Fulani or the Hausa; it is interpreted to mean “cunning” (Bascom Reference Bascom1969:5).

The word “Yoruba,” used to describe a group of people speaking a common language, was already in use in the interior of the Bight of Benin, probably before the sixteenth century. Yarabawa is the plural form for reference to Yoruba, and the singular is Bayarabe. In 1613, Ahmed Baba employed the term or a similar term to Yoruba to describe an ethnic group that had long existed (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy, Falola and Childs2004:41). At the time, the term was not used for any particular subgroup of Yoruba such as Oyo; the Oyo polity was still relatively unknown. Some scholars used “Yoruba” for the Oyo group (Clapperton Reference Clapperton1829:4; Law Reference Law1977), but the term “Yarabawa” or “Yariba” was found among Muslims (i.e., Hausa, Songhai), and also in Arabic very early and long before the rise of Oyo, more as a reference to a whole group than to a specific polity (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy, Falola and Childs2004:41). Some other names or nomenclatures used before the general term, “Yoruba,” discussed in Chapter 9, include Nago as in Brazil, and Lucumi in Cuba and other Spanish colonies in the Americas, as well as in French colonies. In Sierra Leone, they were referred to as “Aku.” “Terranova,” a Portuguese term which referred to slaves taken west of Benin’s territory, was also an early term for Yoruba that fell out of use in Spanish America in the seventeenth century (Lovejoy and Ojo Reference Lovejoy and Ojo2015:358–359).

All these terms (e.g., Lucumi, Terranova, Aku, Nago) can reveal patterns of identity formation of people currently known as Yoruba. They were variously employed by “non-Yoruba” peoples as labels to describe “the other,” which the latter did not use to describe themselves (Lovejoy and Ojo Reference Lovejoy and Ojo2015). The use of these appellations may be based on certain habits, characteristics, origin, location, or other special things that the “non-Yoruba” groups observed in “the other” group. A “Yoruba” identity is important only where other ethnic groups such as Tiv, Hausa, or Nupe are involved (Eades Reference Eades1980:4). However, the conceptualization of the Yoruba as a collective identity dates back to the nineteenth century, through the Christian missionaries and the early Yoruba elite (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006b:30). By the 1890s, when Samuel Johnson (Reference Johnson1921) completed his book, “Yoruba” had been widely used among the early Christian elite to define the land, people, and language (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006b). It seems, then, that the only thing we know about the origin of the word “Yoruba” is that its usage began to spread in the nineteenth century.

Geographical Location and the Yoruba Culture Area

The Yoruba cultural and geographical spaces have adjusted over time, due to migrations within West Africa and beyond. Yoruba people have moved, like many other African groups, and they are continually moving to new areas. The modern map, placing Yoruba mostly in southwestern Nigeria, is a product of the nineteenth century – it does not accurately represent the settlement and migration patterns of the Yoruba before that time.

The war in the mid-nineteenth century significantly altered the Yoruba geographic space (Ojo Reference Ojo1966). The changing rulership of Yoruba-speaking people also changed their landscape. During the height of Oyo’s territorial expansion, Yoruba territory extended as far as Ketu, Idassa, Shabe, Kilibo, and beyond, into the Republic of Benin and Togo, and to the north around the banks of the Niger River (Clapperton Reference Clapperton1829:56; Ojo Reference Ojo1966:18). The creation of international, regional, and provincial boundaries altered and reshaped Yorubaland further, realigning its peoples. In 1889, the Anglo-French international border divided part of western Yoruba. Afterwards, the Yoruba in Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin) lived with other ethnic groups in that area (Ojo Reference Ojo1966:18).

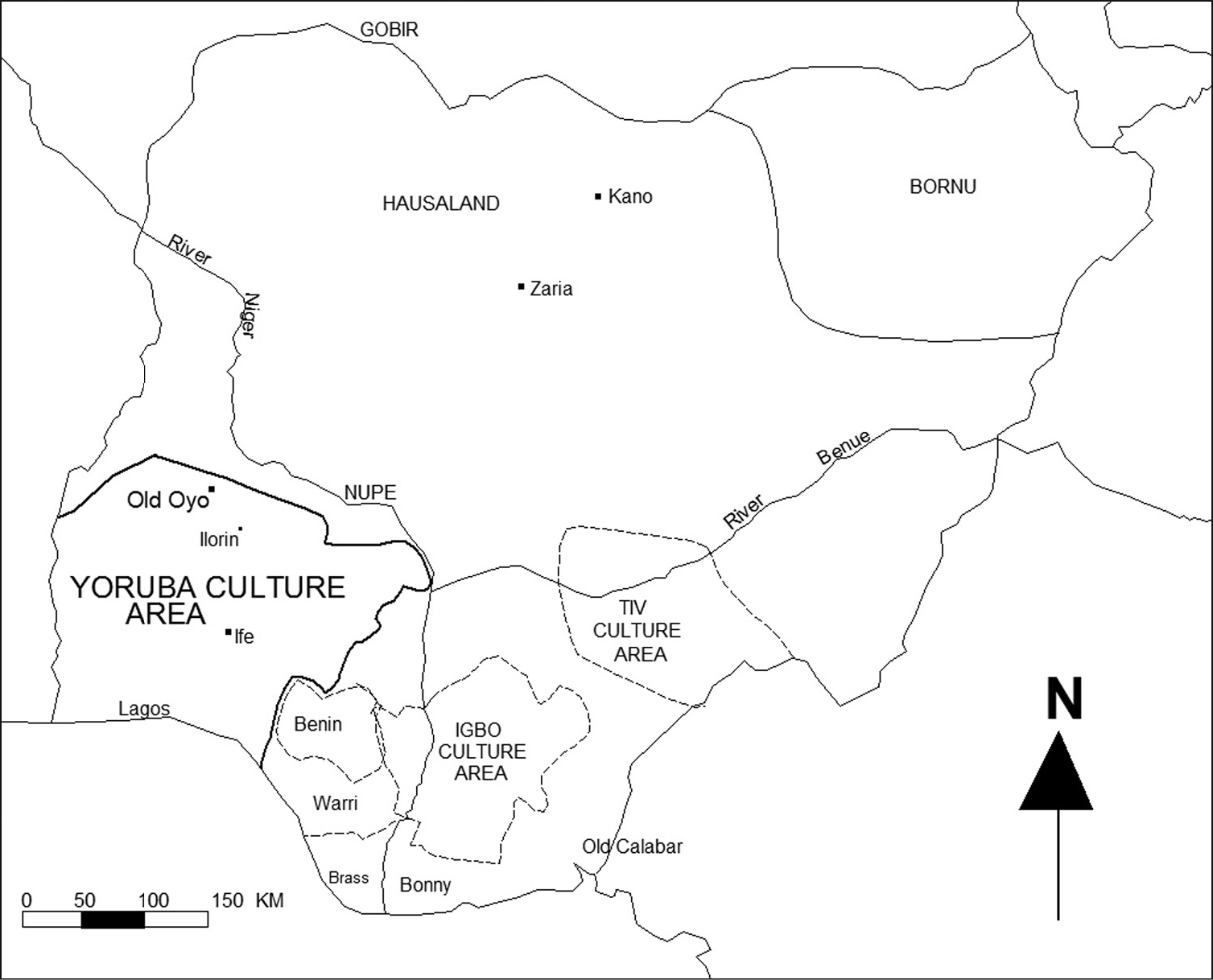

The bulk of the Yoruba currently live in southwest Nigeria, in six states: Ekiti, Ogun, Oyo, Osun, Ondo, and Lagos (Figure 1.2). Large populations of Yoruba people are also in the Kwara and Kogi states in north-central Nigeria. The Yoruba people in Kwara are the most abundant population in their state, but they have become a minority among other Yoruba groups. They are often addressed as northerners by those from the southwest, while northerners do not accept or recognize them as belonging to the north. Nevertheless, the traditional homeland of the Yoruba people is represented by southwest and north-central Nigeria, mainly by parts of Kwara and Kogi states.

Figure 1.2 Postcolonial Nigeria Yoruba states

Some Yoruba are in the Edo and Delta states, as well as other West African countries, such as the Republic of Benin, Togo, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Outside Africa, Yoruba are present in Cuba, Brazil, Haiti, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and the United States of America. Nigerian census figures are often inaccurate, and there are no accurate figures on the total population of Yoruba in Nigeria or elsewhere. However, the total number of Yoruba people in West Africa is estimated to be about 40 million, making the Yoruba one of the largest groups in sub-Saharan Africa (Abimbola Reference Abimbola2006).

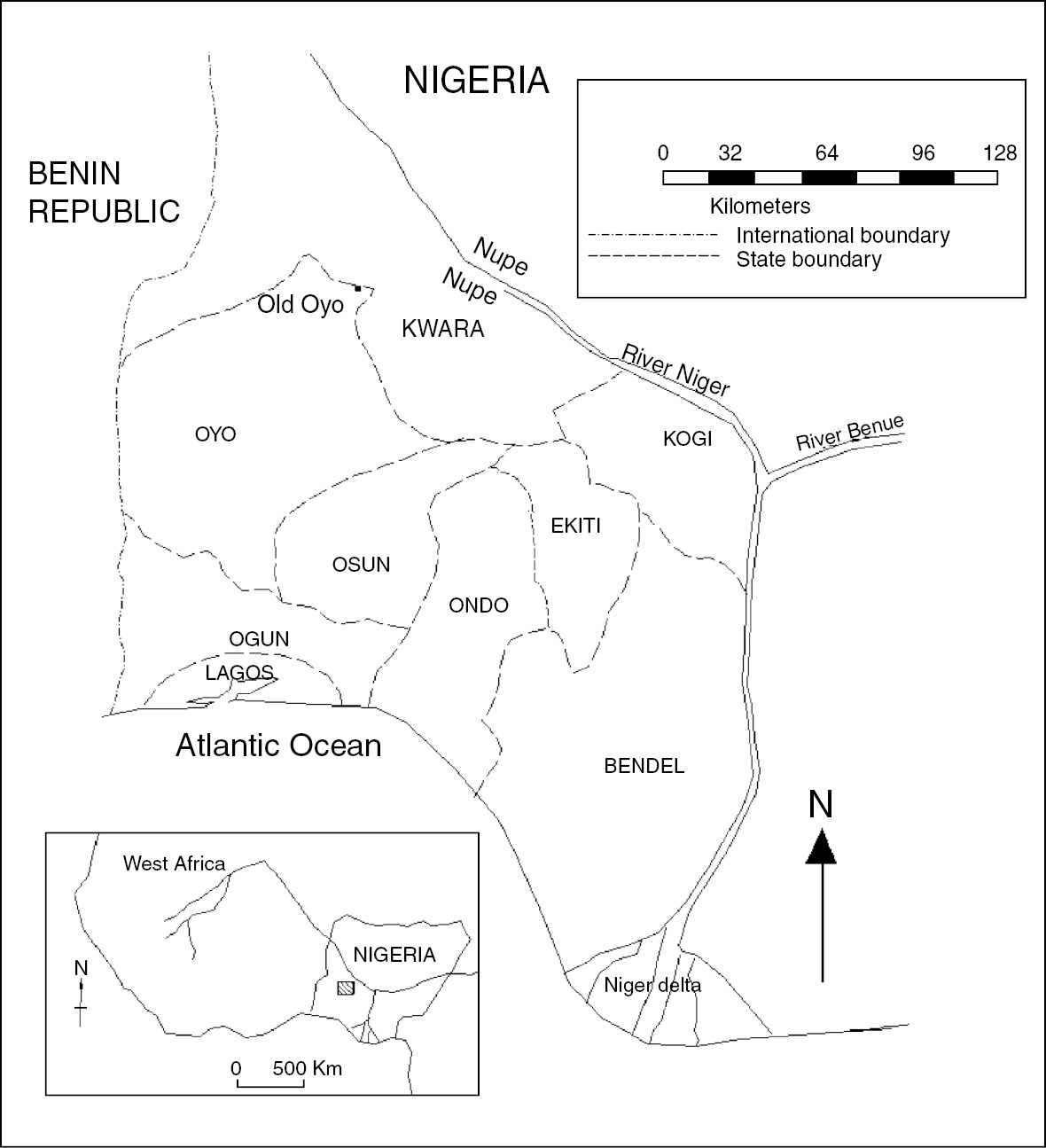

Yorubaland lies roughly between latitudes 6º 0’ and 9º 0’ N and longitudes 2º 30’ and 6º 30’ E, with an estimated area of about 181,300 square kilometers. It falls within three distinct ecological zones (Atanda Reference Atanda1980:1; Buchanan and Pugh Reference Buchanan and Pugh1955:13). The first zone is narrow lowland, going east to west and extending, on average, about 300 kilometers from the coast. It is fewer than 30 meters above sea level. The coast consists of mangrove swamps, lagoons, creeks, and sandbanks, and it forms the southern border of Lagos State and parts of the boundaries of Ogun and Ondo states. North of the coastal area is the second zone, the forest region. It narrows in the west and widens in the east, where it extends as far north as Iwo and Osogbo. The thick forest stretches up to southern Ondo State and Edo State to the east. Deciduous forest in the northwest continues from Abeokuta to Ondo and Owo in the east of Yoruba. Third, and farther north, is the derived savanna zone that extends into the Guinea savanna in the northwest. The area is characterized by rocky surfaces and hills with heights from 300 to more than 900 meters (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Nigeria’s environmental zones

Yorubaland is dominated by north-to-south flowing rivers. The rivers flow into the Niger River, known in Yoruba as Odo Ọya or River Ọya (Bascom Reference Bascom1969:4). Most of the large rivers flow south, such as the Yewa, Ogun, Ọsun, Sasa, Ọmi, Ọni, and Oluwa, emptying into the lagoon (Ojo Reference Ojo1966). This inlet extends eastward from the Republic of Benin to the Benin River, where it links with the Niger Delta creeks. It provides an inland route for canoes as well as an east–west trade route (Bascom Reference Bascom1969; Ojo Reference Ojo1966:23).

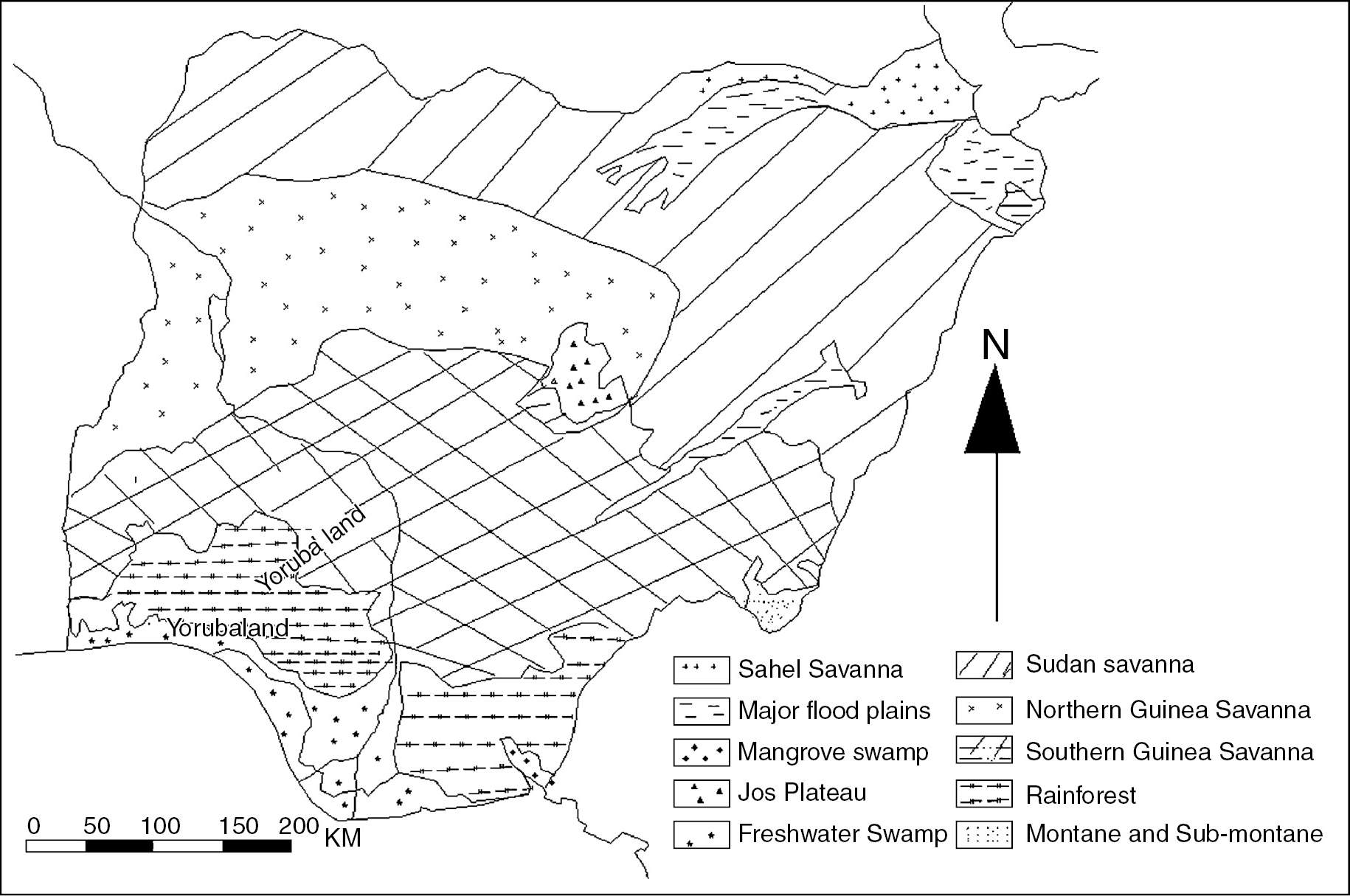

Yorubaland’s temperatures are consistently high, due to its location between about 6º 0’ and 9º 0’ north of the equator (Ojo Reference Ojo1966). Winds blow inland from the Gulf of Guinea in the rainy season, from April to October, and dusty harmattan winds blow southward from the Sahara to bring cooler temperatures in the dry season, from November to February (Bascom Reference Bascom1969). Moisture accumulates in the air from rainfall, dew, rivers, underground water, lagoons, creeks, and coastal water (Ojo Reference Ojo1966). Rainfall levels decrease moving inland from the coast. It rains heavily from June to September, raining along the coast for almost the entire year and raining in the north for at least half the year (Ojo Reference Ojo1966:24–5) (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Nigeria – rainfall distribution

Vegetation in Yorubaland reflects the rainfall distribution, becoming sparser inland. A narrow tract of swamp forest runs along the coastal area, among the creeks and freshwater lagoons. The high forest, located in the southwest, is dry, open, and deciduous. An evergreen rainforest is in the southeast, between the swamp forest and the high forest (Ojo Reference Ojo1966). Derived and Guinea savanna vegetation is in the northern part of Yorubaland. The soil types in Yorubaland are diverse – for example, swamp soils are typical in the swamp forest near the coast, dark mud and clays are in the south, and sand occurs in some other places (Ojo Reference Ojo1966:26).

Yoruba Subgroups, Language, and Dialects

The Yoruba subgroups are the Oyo, Awori, Owo, Ijebu, Ekiti, Ijesa, Ifẹ, Ondo, and Akoko. Others are Egbado, Ibarapa, Egba, Itsekiri, Ilaje, Ketu, Sabe, Idaisa, Ife (or Ana, found today in the Republic of Togo), Mahi, Igbomina, Ibolo, Okun, and others (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:8) (Figure 1.5). Each Yoruba subgroup inhabits a particular region. The Okun Yoruba subgroup inhabits the grassland region in the north, particularly near the Niger–Benue confluence. The Okun is divided into Owe, Oworo, Igbede, Ijumu, Ikiri, Bunu, and Yagba village units.

Figure 1.5 Yoruba subgroups

The Igbomina subgroup occupies territory west of Okun (made up of Yagba, Igbede, Ijumu, Abinu), in the Yoruba northern belt. The Ibolo subgroup is southwest of the Igbomina. The Oyo subgroup, one of the largest, is located west of Igbomina. The territory of the Oyo subgroup extends from the border with the Igbomina in the east to the boundary with the Ketu in the west (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:8).

Located to the south of Okun are the Ekiti and Akoko subgroups, inhabiting the hilliest region of Yorubaland (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). West of the Ekiti is the Ijesa subgroup, and west of the Ijesa are the Ife of central Yorubaland. The Egba subgroup is located west of Ife, and to the north of Egba is the Ibarapa subgroup. This area is the middle belt of Yorubaland, and it is mostly tropical forest, with the grasslands extending into the Ekiti and Akoko territories (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010).

The Owo subgroup is also south of the Ekiti and Akoko subgroups, and west of the Owo is the Ondo, Ijebu, and Awori subgroups. They inhabit the center of the thickly forested part of Yoruba territory (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). The Ijebu and Awori extend farther south to the coast, inhabiting a significant portion of the lagoon.

The Itsekiri, the easternmost Yoruba subgroup, occupy the Atlantic coastland, surrounded by mangrove swamps, creeks, and lagoons. The Ilaje are next to the Itsekiri, and immediately north of the Ilaje is the Ikale subgroup, which occupies a narrow territory that is partly forests and partly swamps. To the west of the Ilaje and Ikale subgroups is the coastal Ijebu subgroup, and west of the Ijebu is the coastal Awori. The coastal Ijebu subgroup occupies the southernmost tip of the large Ijebu subgroup’s territory (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010).

Westernmost Yorubaland, including the middle and south of the Republic of Benin and the western provinces of the Republic of Togo, is home to several small Yoruba subgroups. These are the Ketu, Idasa, Sabe, Ahori, Mahi, Isha, and Western Ife (or Ana) (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). These Yoruba subgroups coexist and closely interact with the Adja (Aja). The Adja’s small population was greatly influenced by the larger Yoruba population. Ultimately, Yoruba and Adja became one cultural area, with the Yoruba language used as the dominant language for the two groups (Akinjogbin Reference Akinjogbin, Ajayi and Crowder1985).

Linguistic evidence suggests that the Yoruba, Igala, Edo, Idoma, Ebira, Nupe, Kakanda, Gbagyi, and Igbo belonged to a cluster of languages, now called the Kwa subgroup, in a broader classification known as the Niger–Congo (or Nigritic) family of languages. The small group was concentrated around the Niger–Benue confluence (Obayemi Reference Obayemi, Ajayi and Crowder1976:200). Glottochronological evidence suggests that these languages slowly separated between 2,000 and 10,000 years ago (Armstrong Reference Armstrong, Vansina, Mauny and Thomas1964), developing distinctive characteristics. The last language groups to separate were the Igala and Yoruba (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:7). The proto-Yoruba and proto-Nupe language subfamilies are said to have migrated up the Niger toward the confluence, and subsequently became differentiated from their mother language group (Obayemi Reference Obayemi, Ajayi and Crowder1976).

Each Yoruba subgroup speaks its dialect of the common Yoruba language. According to Adetugbo (Reference Adetugbo and Biobaku1973:184–185), local Yoruba dialects are divided into three main families: 1) Northwestern Yoruba, spoken in the Oyo, Osun, Ibadan, and Egba areas; 2) Southeastern Yoruba, expressed in the Ondo, Owo, Ikale, and Ijebu areas; and 3) Central Yoruba, spoken in Ife, Ijesa, Ekiti, and Igbomina. These distinct Yoruba dialects mark the internal differentiation among today’s Yoruba subgroups (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010).

Some neighboring subgroups understand one another better. An Ilorin Yoruba would find it difficult to comprehend an Ekiti, while the same Ilorin would merely consider that an Igbomina speaks with a different accent. Similarly, the Igbomina and Okun Yoruba may find it harder to understand each other’s dialect, but an Igbomina would view Ibolo and Ilorin dialects as much easier to understand.

Each subgroup’s dialect is not entirely homogeneous, and local variations exist within all Yoruba dialects. For example, while the entire Igbomina subgroup speaks a Yoruba dialect called Igboona, the various localities of Igbomina, including Ipo, Ilere, Esisa, and Erese, differ slightly in their intonation and pronunciation of specific words. Based on these differences, the Igbomina people have been grouped into Igbomina “Mó yè” and Igbomina “Mó sàn.” The Igbomina “Mó yè” includes Igbomina in Esisa, Esa, Ilere, and Iyangba village groups, while the “Mó sàn” is made of Erese, Ipo, Isin, Ekumesan-Oro, Esie, Share, and Ila village groups (Dada Reference Dada1985:27).

Within the Akoko group, variations in dialects are found from village to village (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). Among members of the Ijebu subgroup, differences in dialect have given rise to four provinces, each identified by a variant of the subgroup’s primary dialect. These four regions are western Ijebu (known as Remo), central Ijebu (around Ijebu-Ode), coastal Ijebu, and northeastern Ijebu (around Ijebu-Igbo) (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:10).

The Ekiti, who occupy rugged hills, had sixteen dialects, translating as the “sixteen heads of Ekiti” (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). The Oyo subgroup’s dialect was homogeneous, though the area is roughly divided into two provinces: the northern and central Oyo territory, and the Epo province to the south (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:11). The Ondo subgroup had four dialects: one spoken by those in eastern Ondo’s area of the Idanre Rock; one used by the northeastern group, around Ile-Oluji; another used among the inhabitants of the deep southern Ondo forests near Ikale and Ilaje; and a final dialect spoken by populations in the rest of the Ondo forests, around Ode-Ondo (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010). Finally, the Egba subgroup has three dialects: Egba Agbeyin; Gbagura, spoken in northern Egba; and Egba Oke-Ona (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:11).

Despite differences in Yoruba dialects, the subgroups share essential cultural characteristics. Tunde Akinwunmi (Reference Akinwunmi, Olukoju, Apata and Akinwumi2003:85) and Asiwaju (Reference Asiwaju and Olusanya1983:28) have suggested eleven features or cultural traits for the core definition of the Yoruba:

i) They claim that their ancestor was Oduduwa.

ii) They regard Ile-Ife as their cradle, or point of first origin.

iii) They all have praise songs, cognomens, or oriki about themselves.

iv) Their greetings commence with “E ku,” “Aku,” or “Okun o.”

v) They were traditionally agrarian.

vi) They form monarchical governments.

vii) They are highly urbanized people.

viii) They believe in Ifa and Ogun deities and the concept of destiny, or órí.

ix) They dress differently from other, non-Yoruba-speaking people.

x) They practice customs specific to the Yoruba people, such as the way they greet elders by prostration and kneeling and the way they conduct weddings and burials.

xi) The lands occupied by the different Yoruba-speaking groups are geographically contiguous.

Neighboring Groups

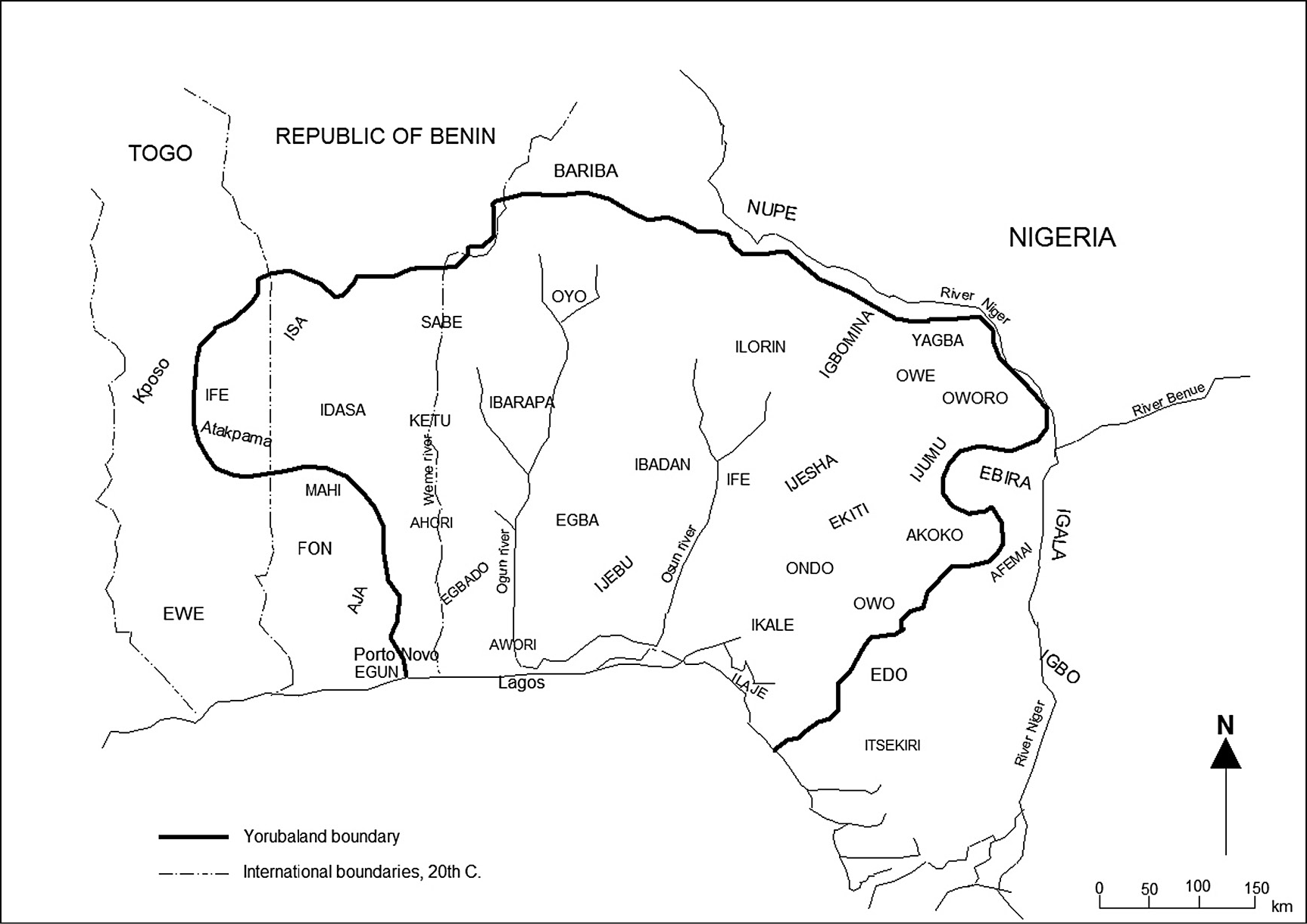

The strategic location of the Yoruba’s cultural area promoted many interactions, first with non-Yoruba neighbors and later with non-African people, mainly the Europeans (Asiwaju Reference Asiwaju and Olusanya1983:28). The Yoruba culture’s strong affinity with neighboring groups, such as the Bariba, the Nupe, the Edo, and the Adja, suggest that they interacted very closely in the past (Figure 1.6). To the west, the Yoruba share territory with the Fon, Mahi, Egun, and other Ewe-speaking groups.

Figure 1.6 Yoruba and its neighbors

Settlements of the Yoruba and Adja overlapped from early times, leading to intense cultural affinity long before the emergence of the great kingdoms of the Yoruba (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:205). The Aja kingdoms included Savi, Weme, Allada (or Ardra), and Dahomey. In addition to the Yoruba’s strong external influence, the Savi kingdoms contained large Yoruba populations.

Dahomey, the kingdom of the Fon people founded in 1625, was a mixture of Adja and Yoruba populations (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:206). By the late seventeenth century, the expansion of the Dahomey kingdom threatened the neighboring Yoruba and Aja. Starting in the late eighteenth century, the decline of Yoruba’s Oyo kingdom provided the opportunity for Dahomey to become the dominant power among all kingdoms of western Yorubaland by the nineteenth century (Akinjogbin Reference Akinjogbin, Ajayi and Crowder1976).

On the northern frontier, the Yoruba share boundaries with the Tapa (Nupe), Bariba, Ebira (Igbira), and Igala. This border does not feature any critical physical barriers such as mountain ranges or large rivers, and the territory of the Yoruba is terminated by a landscape feature at only two locations: the Niger River near Jebba and Lokoja (Obayemi Reference Obayemi and Olusanya1983:77). As a result, the resources, subsistence, patterns of movement, and climatic condition are considered similar on either side of the boundary.

Oral traditions provide evidence of cultural interactions. The Oyo Yoruba and the Bariba occupied the same villages in the western parts of the Middle Niger valley, while the Oyo and Igbomina Yoruba inhabited some of the same communities with the Nupe in eastern parts of the valley (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:206). The Igbomina are said to have adopted the Nupe’s Igunnu masquerade from the Nupe who settled among them, while the Nupe borrowed the Ifa divination from the Igbomina (Babalola Reference Babalola1998:15; Smith Reference Smith1965). The Nupe divination system known as Eba is similar in technique to the Ifa practiced by the Igbomina. Also, Sango, an important god in the Yoruba pantheon, is sometimes linked with the Nupe deity Soko, fixing the emergence of Sango in Oyo-Nupe relations (Law Reference Law1977).

There were also frictions between the Yoruba and these northern neighbors. Nupe intrusions in Igbomina are significant features of the oral traditions, and the narratives indicate that alliances were formed to counter external aggressions. In the sixteenth century, Oyo developed into a dominant, expansionist polity in a process that divided the sociopolitical and economic landscape of northern Yorubaland into a core and a periphery, even as it maintained an ideology of imperial oneness (Usman et al. Reference Usman, Aleru and Alabi2005a). The Nupe, who shared similar ambitions, were a considerable threat to Old Oyo’s expansionist agenda. Oyo needed to defend itself and protect the edges of its newly established domain from intermittent Nupe incursions, especially in northern Yorubaland.

In the Jebba–Mokwa area, the main corridor of Oyo Yoruba and Nupe, evidence shows that Yoruba or Yoruba-related communities were pursued to the bank of the Niger River by the Nupe. Some were “Nupe-ized” as Gbedegi communities (Obayemi Reference Obayemi and Olusanya1983:79). Nupe invasions of Offa, an Ibolo town, forced it to change locations at different times during its early foundation (Obayemi Reference Obayemi and Olusanya1983:79). Today, the Igbomina is a mixture of Fulani, Nupe, and Yoruba, especially in the Ilorin, Igbaja, Idofian, Sare, and Oke-Ode districts (Usman Reference Usman2012). Individuals who claim Bariba, Tapa (Nupe) or other ancestry have settled in northern Yoruba. For example, the entire Ilafe section of Oro-Ago in Igbomina is descended from the Nupe, while a part of the Odo Oko ward of Oko town that practice Igunnu, a Nupe masquerade, is inhabited by descendants of Nupe immigrants (Babalola Reference Babalola1998:15).

The Okun Yoruba subgroup in the northeast occupies the Niger–Benue confluence with other groups, such as Ebira, Kakanda, Afenmai, and Igala, located along the western banks of the Lower Niger. These non-Yoruba societies have interacted with the Yoruba throughout history, resulting in significant similarities in language and other cultural practices. The dialects of the Yoruba subgroups in these areas, notably the Okun Yoruba and Akoko, show the influence of their non-Yoruba neighbors, while those neighbors all speak Yoruba as a second language.

There are remarkable similarities, and occasional differences, in their divination systems. The word for divination among the entire Yoruba is ifa, as well as among the Igala and Ebira (Bascom Reference Bascom1969:70; Boston Reference Boston1968). However, the names for the diviners are different from one linguistic group to the next. For example, the Yoruba refer to the diviner as Babalawo/Abalao, “father of the secret pacts” or Awo, “the knowledgeable one” (Boston Reference Boston1968). Among the Nupe it is Ebasaci, “one who casts the Eba”; and among the Igala the diviner is called Ohiuga, “royal diviner” or “divination specialist” (Boston Reference Boston1968; Nadel Reference Nadel1954).

Linguistically, the northern Yoruba and their non-Yoruba neighbors share a close resemblance in their words for the masquerade. The Yoruba refer to masquerade as egungun or egun. It is called eku among the Ebira, gugu among the Nupe, and egwu among the Igala. In Yoruba terminology, the word eku has the same meaning as ebira eku (Adinoyi-Ojo Reference Adinoyi-Ojo1996). In towns north of Oyo, such as Saki, the word èkú refers to the costume that the masqueraders wear. Frederick Nadel’s study of the Nupe religion has shown that the Nupe word gugu was derived from the Yoruba egungun, even though the Nupe possessed their indigenous masquerade tradition (Nadel Reference Nadel1954).

The diffusion of the masquerade cult into the confluence area, mainly through the Igala, Ebira, and Nupe, brought the need for textiles of varying colors for masquerade costumes. Red cloth, or ododo, was highly valued among the Igala masquerade cult members. It was the exclusive preserve of adult males and royalty (Miachi Reference Miachi1991:345). The Okun Yoruba of Abinu (Bunu) and Ikiri improvised the Igala ododo for their own Yoruba masquerade, weaving the cloth on a large scale (Temple Reference Temple1965:71). The improvised ododo was called upo by the Okun (T. Akinwunmi Reference Akinwunmi, Olukoju, Apata and Akinwumi2003:91). There is also a long Yoruba Ifa tradition that proscribes the use of red fabric as grave clothes (Abimbola Reference Abimbola1977:73–74). The diffusion of masquerade tradition, including elements of the Igala burial system, influenced the Okun Yoruba, and they substituted the pan-Yoruba burial practice with an Igala tradition that supported the use of red cloth (T. Akinwunmi Reference Akinwunmi, Olukoju, Apata and Akinwumi2003). In the Okun region, the introduction of the Igala masquerade tradition came from the Ebira people located close to the Abinu and Ikiri Okun-Yoruba. It then diffused through Obelli and neighboring Abinu villages to the Kabba district (Kenneth Reference Kenneth1931; Obayemi Reference Obayemi and Ikime1980:162).

As early as the sixteenth century, even before the full political consolidation of the Igala kingdom, Igala’s influence through trade had extended to the Niger–Benue confluence area, such as the Okun areas, particularly through the Oworo group (Ukwedeh Reference Ukwedeh2003:194–198). The Igala controlled trade and collected tribute from the Kakanda, Ebira, and Oworo groups, and one impact of these relationships can be found in the traditions of the Oworo people – they suggest that the institution of kingship came from Idah, the Igala political center (Mohammed Reference Mohammed2011:36).

The Ebira settlements of Igu and Opanda, later called Koton Karifi, were the primary trading centers. Jukun traders came along the Benue River to the confluence area, while Igala traders went to the area from the Lower Niger. The Nupe living on the northern and southern banks of the Niger controlled who crossed the river (Mohammed Reference Mohammed2011). Virtually from the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Yoruba were trading with the Nupe to the north and the Igala to the east. This trade exchanged ideas, traditions, and customs. Some of these traditions and customs were incorporated into the cultural practices of the Yoruba.

In the thickly forested southeast region, intensive ethnic interactions have led to mixed populations, related languages, intermarriages, trade, and migrations. Here, the Yoruba share boundaries with the Edo and other associated groups, like the Akoko-Edo, Afenmai, and Esan. The southern half of this frontier was home to the kingdoms of the Owo forests, while the hilly northern territory, with lighter vegetation, was home to the Akoko kingdoms.

Owo territory is separated from the primary centers of the Edo population, and from Benin, by about 80 kilometers, but the Owo and the Edo still influenced each other’s culture. Such influence can be seen in the Owo’s Yoruba dialect, which in turn had a substantial impact on the Edo language (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:211). Some of southern Yorubaland’s oldest and busiest trade routes run through the Yoruba-Edo southern corridor, drawing traders from all parts of Yorubaland. Owo was the principal center of this frontier region, known for its artistic transmission between ancient Ife and Benin. Archaeological evidence suggests that Owo, a major bronze-casting center, benefited from the old Ife and Benin traditions of bronze casting (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:211).

The Yoruba and Edo political institutions and royal regalia share common characteristics, notably their preference for beads. The Owo, Akoko, and most Ekiti kingdoms borrowed some Edo traditions, royal festivals, chieftaincy titles, and styles of palace architecture. Historically, the Owo, Akoko, and southern Ekiti people looked east toward Benin kingdom for inspiration as well as west toward the primary centers of Yoruba polities (Akintoye Reference Akintoye2010:212).

Social and Political Organization

Anthropologists from African and European backgrounds, along with sociologists, historians, and others, have written extensively on Yoruba social organization (e.g., Bascom Reference Bascom1944; Eades Reference Eades1980; Fadipe Reference Fadipe1970; Forde Reference Forde1969; Johnson Reference Johnson1921; Lloyd Reference Lloyd1955). This chapter mostly analyzes the past, covering a period up to the middle of the twentieth century. Some social practices are still observed in our day, and many have changed. For a better evaluation of Yoruba kinship, Eades (Reference Eades1980:51) has presented four general propositions. First, the Yoruba kinship system is bilateral in all areas of Yorubaland. Second, Yoruba kinship in practice has a patrilineal emphasis in most areas. Third, considering co-residence, rather than genealogy, may be crucial for understanding some aspects of social structure (e.g., Fadipe Reference Fadipe1970; Johnson Reference Johnson1921). Lastly, the Yoruba society is dynamic and constantly changing; differences in social organization in different areas are the consequence of historical processes, as well as a response to political and economic forces.

The basic kin terms of the Yoruba include father, bàbá; mother, ìyá; senior sibling, ẹgbọn; junior sibling, àburo; husband, ọkọ; wife, iyawo or áyá; affine (in-law), àna; child, ọmọ; and others. These terms specify relationships precisely, and they are frequently used to include distant kin, or even non-kin (Eades Reference Eades1980:51). The Yoruba also borrowed some English kin terms such as mama, dadi, buroda (“senior brother”) and anti (derived from “aunt,” but meaning “senior sister”).

Yoruba terminology related to lineage or descent group varies by areas or Yoruba subgroup, but they have the same meaning. For example, the Oyo Yoruba term for descent group is idile, which means the “stem” or “root” of a house (Eades Reference Eades1980:52). In Osogbo, Ekiti, and Ijebu, descent groups are called ebi (Lloyd Reference Lloyd1962). In Oyo, this term, which is derived from bi, “to give birth,” could be used to describe a kin group. In Ondo, an idile is a part of a larger ebi (Bender Reference Bender1970:76). A critical Yoruba kinship term, associated with inheritance and succession, is omoiya, a group of children sharing a mother (Eades Reference Eades1980:52). In a practice that is now obsolete, a deceased man’s property would be divided into equal shares between each group of omoiya, irrespective of the number of individuals in each group.

The Yoruba social organization formed a peculiar architecture: many families, all members of a lineage, would live together in large homes. Each lineage home or extended family home was called a lineage compound, or agbo-ile. The compound was a single sprawling building in which apartments inhabited by the idile (descent groups or the extended family) and some strangers (alejo) were placed around open courtyards. Each nuclear family occupied one apartment, but all the children were raised as a group within the compound.

Due to the strong patrilineal focus of Yoruba kinship, residence after marriage would be patrilocal – young men brought their wives to live with them in their lineage home after marriage. A woman would frequently remain in her husband’s compound after his death, marrying a member of his kin group or staying on with her children. In the past, most women married husbands from the same village or town. This allowed them to maintain close ties with their family compounds, retaining their rights of inheritance there (Eades Reference Eades1980:52). Each lineage was very protective of its name and honor, regularly imploring its members to conduct themselves appropriately.

Seniority was, and still is, very important in the Yoruba social structure. Rank among members of a compound is generally determined by birth order. However, a woman’s position in her parents’ compound would be defined by birth order, and then her position in her husband’s compound would be defined by rule of marriage (Eades Reference Eades1980:53). A woman would be junior in rank, and submissive in the compound, to all women who married before her and to all children born before her arrival (Bascom Reference Bascom1942; Eades Reference Eades1980). Junior members of the compound were required to use the correct forms of address for senior relatives, and, in the case of wives, to co-wives and affines.

The leading authority within a Yoruba compound or descent group rested with the elders, often with the oldest male member. In some areas, the compound’s head is known by the title bale (a formation from baba ile, father of the ile; sometimes also addressed as olori ile, head of the ile), and in other places as the olori ebi (head of the ebi). The bale traditionally exercised authority over matters such as discipline; settling disputes; allocating living space, work, and land; and arranging marriages (Eades Reference Eades1980:53). If the bale was in declining health, his role was performed by the next most senior. In some cases, the bale was a link between the compound, the wards (various compounds), and the political authorities in the town.

The general rule of inheritance in Yorubaland was that property only passed between blood relatives. In the past, families had rights over the siblings and children of the deceased (Lloyd Reference Lloyd1962). In the nineteenth century, a wealthy man’s wives and children would have been considered part of his property, and they would be inherited by his full siblings (Eades Reference Eades1980:55). In the present day, a man’s property acquired through his labor is passed to his children, while his inherited estate would go to his siblings. Women frequently earned their wealth through trade. And while a wealthy man’s property would usually be divided between multiple children who could have different mothers, a woman would pass most of her estate on to her children alone (Eades Reference Eades1980:56).

Marriage is prohibited between partners who are related by blood, no matter how distant (Fadipe Reference Fadipe1970:70; Lloyd Reference Lloyd1966a:488). In the past, average ages of marriage were between 25 and 30 for men, and between about 17 and 25 for women (Eades Reference Eades1980:57). Although there are variations in marriage customs across Yorubaland, a broad measure of commonality can also be found. First marriages used to be arranged by parents, and lengthy inquiries were made by relatives – investigating to avoid partners whose families were known for dishonesty, debt, hereditary diseases, witchcraft, and other vices. When the relatives’ inquiries were satisfied, the man’s family would approach through an intermediary, and the Ifa oracle would be consulted.

The usual way of rejecting a suitor was by claiming that the Ifa did not approve or “say well” (Fadipe Reference Fadipe1970). If the relatives’ request was granted or favorable, a marriage presentation ceremony, called isihun, would follow to establish contractual obligations between the groups (Fadipe Reference Fadipe1970:72). The final presentation, usually called idan, was made before the transfer of the bride to her husband’s house (Eades Reference Eades1980:57). Today, marriage ceremonies are often occasions for conspicuous consumption, or to show off one’s strength – or the strength of the relatives – with substantial money spent on food, drink, clothing, and entertainment.

In the precolonial period, and probably up to the 1970s, divorce in Yorubaland was uncommon. The continued involvement of relatives in the married couple’s life meant that they would quickly intervene to help resolve differences (Fadipe Reference Fadipe1970:90). Common reasons provided by women seeking divorce included financial neglect, problems with co-wives, issues with in-laws, and barrenness, although claims of infertility were often due to pressure from the husband’s relatives. If the husband was impotent, the descent group could find a substitute. During the colonial period, divorce applications were approved almost automatically after repayment of the husband’s marriage expenses. Today, Yoruba men rarely take their wives to court for a divorce; a man who wants to divorce his wife will just stop caring for her.

The age sets, title associations, and traditional religious cults have mostly declined or disappeared in most parts of Yorubaland. Replacing them are other forms of social organizations based on age, religion, and occupation. The most popular type of association is the ẹgbẹ, which is found in nearly every town. An ẹgbẹ usually begins as a small, informal group of friends from the same ward or neighborhood, of the same age, gender, and religion. The ẹgbẹ holds regular meetings, contributes money, arranges dances, and chooses the cloth used for its uniform (asọ ẹgbẹ) during religious festivals (Eades Reference Eades1980:61).

In larger towns, there are occupational ẹgbẹ, extending to market trades and crafts. They range from tailors’ and photographers’ associations to cloth sellers and local soap makers, each with its officials and regular meetings (Eades Reference Eades1980). Some of the occupational ẹgbẹ attempt to regulate prices and control quality, while the traders’ ẹgbẹ pressure the government to improve market amenities or to reduce taxes and license fees. Many occupational ẹgbẹ run esusu, rotating credit associations that settle disputes in the market or assist members with some expenses, such as naming ceremonies or funerals (Eades Reference Eades1980:61).

Many Yoruba villages and towns have parapọ, or town-improvement associations. Membership is open to all indigenes, whether they live inside or outside the town. These town unions, which developed in the 1920s and 1930s, were first organized by educated migrants in Lagos and other large towns before spreading to virtually all areas of Yorubaland (Eades Reference Eades1980:62). The associations have elected officials and constitutions. Sometimes, delegates from each branch or chapter return home during festivals for an annual general meeting. The unions make monetary contributions or payments toward development projects at home, such as a new church or mosque, a town hall, a health center, a new market site, or a school renovation, or they donate materials to schools and health centers in the town.

The parapọ unions are directly related to unequal levels of development in different areas and the government’s dwindling allocation of amenities. A parapọ’s members often pressure or lobby the town’s indigenes in high positions in the civil service or army, emphasizing the need for specific projects or developments in their town. In the 1930s, the town associations started to participate in local politics, and some of their members, representing the new commercial and educated elite, were later elected as councilors, legislators, or party officials (Eades Reference Eades1980:62).

The institution of chieftaincy is an age-old cultural heritage of the Yoruba. One cannot say precisely when it started, but politics is associated with the formation of rules and regulations to benefit society. The emergence of Yoruba societies created the need for power, status, and influence.

Before the nineteenth century, chieftaincy institutions in Yorubaland seem to have varied with the nature of the families or lineages that made up the society in question. For example, where the rule was over traditional landowners and immigrants, chiefs were usually recruited from one or more of these lineages (Usman Reference Usman2012:69). This followed the “principle of the first arrival” (Oguntomisin Reference Oguntomisin, Andah and Okpoko1988), with seniority claimed by the family that was first to arrive or settle in the area. The leader of the founding lineage, the first settler, usually took the leadership position of the settlement. Leaders of families arriving later were ranked in seniority beneath the founder. In some situations, a chief was recruited from one of the later-arriving lineages, while landowners retained specific political and ritual duties and obligations (Obayemi Reference Obayemi, Ajayi and Crowder1976:207–8). All leaders acquired a title that became hereditary to their families.

According to Falola (Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006a:163), at least two forms of power structure emerged among the Yoruba. First were the town polities that shared several common characteristics. Here, the overall head was the ọba alade (a crowned king), or an uncrowned ruler, the baalẹ, the olu, or the ọlọja, who controlled subordinate villages. Every ọba, baalẹ, olu, or ọlọja had a council of chiefs, chosen from the dynastic lineages that constituted the core of the town or village. Representatives from other groups in the community, such as women or trade guilds, were included in the council whenever needed. The town or village was divided into different quarters, each with a chief (the ijoye adugbo). A quarter or ward comprised many compounds of extended families.

After town polities, the second form of government was the centralized administration, which operated in kingdoms or states, notably in Ile-Ife, Ijebu, Ijesa, Ondo, Oyo, and Ila. A kingdom is made up of a capital or metropolis along with several subordinate settlements. Non-centralized polities were also present among Yoruba groups such as the Ekiti, Igbomina, Ondo, Owo, and Awori (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006a:163). In most of these, their towns or villages represented the highest level of political organization.

Irrespective of the polity’s structure, the ọba, baalẹ, olu, ọlọja, and other political functionaries exercised power and enjoyed privileges. The ọba is the highest rank in the traditional Yoruba political structure, and the ọba lived in the capital or head town with his chiefs, where they carried out the executive, legislative, and judicial functions of the kingdom. The ọba held absolute power – to his people, he was both the king of the living world and a companion of the deities. Indeed, some ọbas were treated like gods, or deified after their mysterious death and worshipped as gods, as in the case of Owanise of Ilesa or Sango of Oyo (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006a:163).

The ọba was considered semi-divine and regarded by the people as alase ekeji orisa, the commander and companion of deities, set apart from his subjects by the spiritual powers he acquired at his installation (Eades Reference Eades1980:95; Johnson Reference Johnson1921). In the past, the ọba was rarely seen in public, and when he was, his face was hidden by the ade with its beaded fringe. The right to wear the ade is a privilege among the Yoruba rulers (Asiwaju Reference Asiwaju1976a).

The king is also known as kabiyesi, a condensed form of the expression “ki a bi nyin ko si,” or “Nobody questioning your authority” (Afe and Adubuola Reference Afe and Adubuola2009:117). In Yorubaland in general, people accorded the highest respect to the kings and their office, often believing that to treat them otherwise disobeyed the wish of the gods, risking the gods’ wrath (Afe and Adubuola Reference Afe and Adubuola2009). In theory, the ọba possessed the power of life and death over his subjects, but he was more of a constitutional monarch in practice. The council of chiefs, who represented the major lineages of the town, acted as checks on a king’s actions and activities. A tyrannical ọba would face sanctions, which varied from one society to another. In Oyo, the Oyomesi (the seven hereditary non-royal lineage chiefs) served as checks to the power of the alaafin (king). In other parts of Yorubaland, such as Akure, the deji was required to rule with some groups of chiefs that included the Iare, Ikomo, Ejua, Ogbe, and Owose (Afe and Adubuola Reference Afe and Adubuola2009:118).

The ọba’s political administration of the kingdom was supported by the baalẹ, olu, or ọlọja, who headed small-scale or subordinate polities in the periphery or provinces. They were almost independent, but they had no power over external relations. These authorities were required to pay tributes to the ọba, and they occasionally needed to contribute soldiers when the kingdom was attacked.

Ward chiefs and compound heads enjoyed a degree of power as well. The compound head, watching over the welfare of his compound’s members, was responsible for supervising his people while they engaged in collective work. He also assisted ward chiefs by sending people for communal labor. The ọba and baalẹ made laws, but the implementation was done in association with the ward chiefs and compound heads.

There were different courts: the court of the compound head, the court of the ward chief, and the court of the ọba or baalẹ. The compound head settled disputes between the members of his compound. An appeal could be made to the court of the ward chief, where inter-compound disputes were also resolved. In most Yoruba societies, the ọba’s court was the final place for appeal. However, among the Egba and Ijebu, the Osugbo and Ogboni societies played similar leading roles in judicial matters (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006a:164).

The chiefs’ power extended to the economy, making laws on prices of commodities, maintaining trade routes and markets, and performing other functions. For effective monitoring, most markets were located near the residences of the rulers and chiefs. The chiefs derived wealth from their farms’ production, and their farms were usually the largest in the settlement due to their monopoly over labor (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006a:164). Chiefs also had access to gifts, fines, tributes, tolls, and profits from trade. All chiefs had opportunities to acquire these payments, but the ọba was usually the richest and received the lion’s share of the fines, tributes, and tolls (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006a). A portion of the wealth collected by the chiefs and the ọba was redistributed back to the people through rituals to the gods and feasts held during annual religious festivals.

Elaborate rituals took place whenever a new ọba ascended the throne – the ọba went into seclusion to undergo initiation and instruction for his new role. In Yorubaland, the succession of kings differed from place to place. Usually, the royal family split into several “ruling houses,” each occupying the throne in turn. Often, more than one candidate was presented or indicated interest in the throne. The elders of royal descent would make a preliminary selection, and the senior chiefs, in consultation with the Ifa oracle, would make the final choice. In Oyo, primogeniture was the usual succession rule until about 1730. Afterwards, the Aremo, or the alaafin’s eldest son, would be expected to die with his father; that practice came to an end in 1859 (Eades Reference Eades1980:95).

To summarize some of the main points of this chapter: the Oduduwa legend at Ile-Ife marks the central point of Yoruba history. Ile-Ife is considered the cradle of the Yoruba, and Oduduwa the progenitor of the Yoruba. Genetic similarities between the Yoruba language and other Kwa-family language groups suggest that the speakers of these languages must have shared a common origin. These similarities cast doubt on theories placing the original home of the Yoruba people outside their present geographic region. Researchers have considered other centers of Yoruba settlement outside Ile-Ife, and these settlements existed before or correspond with the advent of Oduduwa. Therefore, there is a period of Yoruba history before Oduduwa about which much is still to be known. However, the conceptualization of the Yoruba as a collective identity dates back to the nineteenth century, through the Christian missionaries and the early Yoruba elite (Falola Reference Falola, Falola and Genova2006b:30).

The Yoruba are divided into subgroups, and each speaks its own dialect of the common Yoruba language. The dialects are distinct from one another, and they indicate internal differentiation among today’s Yoruba subgroups. The location of the Yoruba culture area promoted interactions, not only between the Yoruba groups but with non-Yoruba neighbors, other African groups, and Europeans. The Yoruba society is dynamic and continually changing, and differences in social organization in different areas are the consequence of historical processes, and a response to political and economic forces.