Sermons, Plays and Note-Takers: Hamlet Q1 as a ‘Noted’ Text

The Actor-Pirate

In the eighteenth century, when Shakespeare editors first came into being, only two texts of Hamlet were known, one printed in 1604 in quarto (now called Q2), and one in the Folio of 1623 (F). But in 1823 Sir Henry Bunbury discovered a third version of Hamlet ‘in a closet at Barton’.1 Dated 1603, it was the first and earliest printed text of the play (now known as Q1). It was also, as shocked scholars realized, the ‘worst’. As one of the earliest commentators on the text, Ambrose Gunthio (probably J. P. Collier) asked, ‘Can any one for a moment believe that Shakspeare penned this unconnected, unintelligible jargon?’2 Since then, critics have repeatedly drawn attention to Hamlet Q1's incoherence, inconsistencies, ellipses, reworkings and loose ends, generally concluding, with G. R. Hibbard, that ‘the text itself,…is a completely illegitimate and unreliable one’. So how did such a text come about – and why?3

Finding an answer is difficult, partly because the text is not equally ‘bad’ – or even ‘bad’ in the same way – throughout. Running at about 2200 lines (the other texts are Q2 c.3800 lines, F c.3570 lines) Hamlet Q1 is more filled with gaps and summaries than the other texts. Yet its earliest pages are fairly true to Q2 and F, while some later sections are quite accurately represented, including speeches by the Ghost and Horatio. Though some passages reflect their Hamlet counterparts almost line-by-line, even if full of synonyms and rephrasings, others are partially, and some entirely, ‘new’.

Early explanations for Hamlet Q1 included the notion that it combines Shakespeare's Hamlet with bits of the lost earlier text on which it was based, the ‘Ur’ Hamlet; or that it is Shakespeare's rough draft. Yet Hamlet Q1 contains textual moments from Hamlet Q2, thought to be a pre-performance text, and F, thought to be a post-performance text – meaning that, in chronological terms, it seems to be the middle text of the three. Another early explanation was offered by ‘Gunthio’: that Hamlet Q1 must have been ‘taken down piecemeal in the theatre, by a blundering scribe’.4

There were good reasons for believing that Hamlet Q1 had been constructed by scribes in the audience. Several sermons of the 1580s and ’90s had been published not from authorial texts, but from notes taken down by the congregation in ‘charactery’, an early form of shorthand; if sermons could be ‘taken’ in this way, why not plays? Anthony Tyrrell's A Fruitfull Sermon of 1589, for instance, broadcasts on its title‐page that it has been ‘Taken by Characterye’; Stephen Egerton's Ordinary Lecture (1589) is, says its title‐page, ‘taken as it was uttered by characterie’. Henry Smith's Sermon of the Benefite of Contentation (1590) is also ‘Taken by characterie’; while his Fruit[full] Sermon (1591) ‘being taken by characterie, is now published for the benefite of the faithfull’. So usual did it become to publish sermons from audience's shorthand ‘characterical’ notes in the 1590s that ‘L.S.’ had to explain, when he provided his own sermon text in 1593, that in this instance ‘Taken it was not from the Preachers mouth by any fond or new found Characterisme’.5

It was the evidence of these sermons that led W. Matthews, in the 1930s, to learn ‘charactery’ in order to determine whether it really could be used to capture Shakespeare. He recorded his conclusions in a series of articles: that charactery has too few words – 550 (if particles are included) – to record a literary text; that it is too difficult a system to be used at speed; and that, using pictorial symbols to represent words – in principal it could be ‘read’ by a foreigner – it is anti-literary, recording only the meaning, not the sound, of any text.6 He and other scholars then worked on the two further shorthands published before Hamlet Q1: brachygraphy (1590), which was also pictorial; and stenography (1602), the first phonetic shorthand. They found inadequacies in all of them, and dismissed the entire notion of scribes in the audience.

In 1941, G. I. Duthie, in The ‘Bad’ Quarto of ‘Hamlet’, accepted Matthews's rejection of shorthand, adding that a shorthand writer, confronted with a word he did not know, would be brought to a standstill, and suggesting that visible note-takers in the audience would, anyway, have been caught and removed. He then offered his preferred explanation for the origin of Hamlet Q1. Summarizing ideas promoted by Dover Wilson, but originating with Tycho Mommsen in 1857, Duthie argued that Hamlet Q1 had been stolen by a traitor-actor who had been involved in the play's production. As Duthie saw it, the hireling who had played Marcellus and Lucianus ‘stole’ the text of Hamlet, reproducing his own part(s) and memorizing what he could of the others. Hence the reason, he said, that Marcellus's part was ‘good’. Since Duthie, most scholars have accepted the idea that Hamlet was taken by a traitor-actor; in 1992 Kathleen Irace furthered it with her computer-based analysis of the part of Marcellus: she suggested, however, that the Marcellus player was reconstructing an adapted form of Hamlet from memory.7 As Hamlet Q1 had long been said to be a ‘pirate’ text, ‘pirate’ meaning, bibliographically, a work belonging to another which has been reproduced without authority, the actor-thief was said to have been a ‘pirate’ – picking up on a joke first made by Alfred Pollard in his Shakespeare's Fight with the Pirates (London, 1917). Over time, however, the joke has been forgotten, and the player of ‘Marcellus’ has come to be called the ‘actor-pirate’, despite the fact that a ‘pirate’ is a plunderer of ships, not a land thief.

The glamorous word ‘pirate’, and the confused notions that it accrued, may have kept alive the theory of the actor-thief. No longer was Hamlet Q1 a disappointingly inaccurate text; it was now an enthralling record of insubordination inside Shakespeare's very playhouse, run, or masterminded, by a rogue ‘pirate’ actor. Yet the actor-pirate theory is inherently problematic. Even in 1.1, Marcellus, as well as Horatio and Bernardo, ‘make mistakes’ and ‘have recourse to synonyms’.8 More damning still for an actor-based theory is the fact that ‘Marcellus’ misremembers his own cues. An actor's ‘part’ for Marcellus – the script that an actor would receive, consisting of his lines and cues – made from Q2/F would look like this, with the words ‘desperate with imagination’ cueing ‘Let's follow’:

But in Q1, Marcellus's part would look like this – with ‘desperate with imagination’ cuing ‘something is rotten’ and ‘will this sort’ cuing ‘Lets follow’ – meaning that the cues are reversed and misremembered:

Marcellus also does not remember to give out his cues to his fellow actor. Q2/F has

But Q1 has instead ‘And leegemen to the Dane, / O farewell honest souldier’, meaning that Marcellus neglects to stop at his cue for Francisco.9 It is unfortunate for the actor-pirate theory that it does not take acting into account.

There are further problems with the actor-pirate explanation. All of the early pages of Hamlet Q1, not just Marcellus's part, are relatively ‘good’, but the more the play progresses, the more is sense, rather than word, recorded. This demands an actor who begins the play with verbal recall, but who, over time, becomes more retentive of sense than sound: a change particularly unlikely for an actor, who usually remembers sound over meaning. Moreover, though in Act 1 the text is sometimes better when Marcellus is on stage, that notion falls apart later in the play, as Paul Werstine points out. Not only are lines surrounding the putative actor-pirate often as bad as lines elsewhere, but also, conversely, sometimes ‘Q1…provides us with a better version of some Q2/F dialogue when the putative reporters are off than it…does when they are on.’10 Attempts to explain this have resulted in casting the ‘pirate’ in ever more roles. Though on the one hand said to be a temporary, hireling actor, with no qualms about stealing the playhouse's property, the actor-pirate has, on the other, been said to have played Marcellus, Voltemand (‘Voltemar’), Lucianus, Prologue, Second Gravedigger, Churlish Priest, an English Ambassador and a scattered selection of mutes – thus becoming one of the most continuously staged players in Hamlet.

The question of actor-piracy, moreover, depends on fusing two different ideas together: that actors might be textual thieves (for which there is no evidence); and that people with very good memories were able to steal plays (for which there is plenty of evidence). In Spain, there are records of men who could hold entire plays in their heads. Luís Remírez, in 1615, was said to be able to reproduce a comedia having heard it three times; while Lope de Vega in 1620 inveighs against audience-members who make their money ‘by stealing the comedias…saying that they are able to memorize them only by hearing them’.11 Maguire points out, however, ‘in neither case are actors involved in the reconstruction’.12 Both instances in fact bolster the argument for locating textual theft amongst the spectators. Moreover, the Spanish memorizers are praised, or blamed, for being unusual: not anyone could perform such feats of memory, and these men are said to have trained with textual theft in mind.

Recently, the more general idea that Hamlet Q1 comes directly from a single actor at all has been implicitly questioned by the work of Paul Menzer, who shows the text to be, because of its poor cues, unstageable; while Lene B. Petersen indicates that Hamlet Q1 is not simply ‘memorial’: its features of repetition and simplification, though reminiscent of folktales and ballads, render it neither fully authorial nor fully ‘oral’.13

Given problems with the ‘actor-pirate’ theory, this article will return to the explanation for which there is historical evidence: audience notation. This is an idea that has been revisited with respect to King Lear in P. W. K. Stone's excellent The Textual History of King Lear (London, 1980), which argues that King Lear Q1 is a reported, but not a shorthand, text, and Adele Davidson's Shakespeare in Shorthand (Newark, 2009), which argues conversely that King Lear Q1 is a shorthand text, and that it was copied from manuscript, not from an audience report. Both books deserve to be better known than they are, but both saddle themselves with a quarto that is particularly receptive to other explanations, and further limit themselves by insisting on one notation, shorthand or otherwise, for bringing the play about.

This article, changing the terms in which Matthews and Duthie originally asked and rejected the shorthand option for Hamlet Q1, will investigate not whether one person, using one form of shorthand, on one occasion, copied Q1 Hamlet, but whether some people, using any form of handwriting they liked, on any number of occasions, could have penned Hamlet Q1. It considers evidence that plays, like sermons, were noted during performance; it looks at what might constitute ‘note traces’ in the text of Hamlet and asks why watchers might want to capture in notes – and then publish – the uttered performances that they heard.

Noters at Churches and Playhouses

As there is detailed evidence about the way congregations rendered the sermons they heard into written texts, this section will start by examining church practice; it will then turn to other oral performances captured in text – parliamentary speeches – before looking, finally, at plays. Did theatrical audiences sometimes transcribe what they heard?

Just as contemporary students are expected to take notes in lectures to facilitate their memorizing and learning, so congregations in early modern England were expected to take notes at sermons ‘for the helping of their owne memories’ while listening, and ‘for their owne private helpe and edification’ afterwards.14 As Lady Hatton wrote to her son Christopher in Cambridge, ‘Heare sermonns’, enjoining him to ‘strive to take notes that you may meditate on them’.15 John Brinsley, in his educational treatise Ludus Literarius (1612), recommends instilling the note-taking habit in children as early as possible. In order to ‘cause every one to learn something at the sermons’ he suggests that young children, if they can write at all, ‘take notes’. The distinction between partial ‘notes’ and whole sermons, however, was permeable; Brinsley goes on to suggest that children in the highest forms at school should ‘set downe the substance exactly’.16

As literacy increased over time, churches became so full of noters as to resemble schoolrooms. In 1641 ‘boys’ at sermons are castigated for turning the communion tables into a surface on which to write, ‘fouling and spotting the linnen’ in the process.17 By 1644, Robert Baillie, participating in the Westminster Assembly, recorded that in England ‘most of all the assembly write, as all the people almost, men, women, and children, write at preaching’; by 1651 Lodewijck Huygens went to church in Covent Garden and found ‘In the box next to ours three or four ladies…writing down the entire sermon, and more than 50 other persons throughout the whole church…doing the same’.18

Preachers from the 1590s onwards had to decide what to think about the sea of ‘noters’ that confronted them. Stephen Egerton concluded, carefully, in 1592, that

I do not mislike the noting at Sermons, but rather wish it were more used then it is, so it were used to keepe the minde more attentive in the time of hearing, to helpe the memorie after hearing, that men might be more able afterwards to meditate by themselves, and to conferre with others.19

He may have been affected by the fact that the popularity of preachers could be measured by the number of noters they attracted.

Naturally, notes of sermons by popular preachers had a tendency to make their way to the press. Sermons that are described as having been ‘gathered’, ‘taken’, or ‘received’ from ‘the mouth’ of a preacher, advertise that they are printed from notes and are not directly ‘authorial’. John Dod's The Bright Star claims, on its title page, to have been ‘gathered from the mouth of a faithfull pastor by a gracious young man’ (1603); William Crashaw printed sermons by William Perkins, ‘taken with this hand of mine, from his owne mouth’ (1605); while Robert Rollock's Scots Certaine Sermons (1599) were likewise printed from a text ‘we / fand in the hand of sum of his Schollers quha wrait at his mouth’.20 Such texts draw attention to the two body parts they manifest, mouth and hand, highlighting their inscripted orality, rather than their literary features.

One ramification of the noting habit was that notebooks needed to be created capable, in size terms, of recording about an hour's worth of preaching (sermons at the time being measured by the hour‐glass).21 Rather than taking to church the pens, ink, sand, knives, paper and blotting-paper that permanent text required, congregations seem often to have opted for ‘tablebooks’ – small notebooks that could be written on with graphite pencils or soft-metal pens. In 1625, Hall refers to the man who ‘in the middest of the Sermon puls out his Tables in haste, as if he feared to leese that note’ (in fact all he actually records is ‘his forgotten errand, or nothing’): tablebooks were a stylish accoutrement, and some people wanted to draw attention to the fact that they had them.22 Those who hoped to be ‘noted’ (‘seen’), flourishing the writing implements that advertised their literacy and their piety, were the subject of a weak pun repeatedly used. The playwright Thomas Heywood, in a 1636 text he himself noted from utterance (it is ‘taken’ from the ‘mouthes’ of two phoney-prophets), depicts a religious hypocrite as one who, ‘In the time of the Sermon…drawes out his tables to take the Notes,…still noting who observes him to take them’.23

Tablebooks had several advantages: they encouraged continuous writing, as they were not reliant on dipping a pen in ink; they were portable – surviving examples are 16mos in 8s; and they were economical, as they could be wiped clean with damp bread or a wet sponge once their notes had been transcribed onto a permanent medium.24 Daniel Featley depicts, using the well-worn pun, the ‘noted noters of sermons’, as they prepare to attend a church: they ‘cleanse their table-books, especially before your fast sermons’.25

A second ramification of the noting habit, especially for those who wished to take an entire sermon, was that speedy writing became a goal: the more swiftly one could write, the more sermon one could gather. As early as 1569, John Hart's Orthographie had recommended using italic rather than secretary hand when taking notes, and avoiding unsounded or unnecessary letters; in effect, he had created the first shorthand, though his was still reliant on the alphabet. From then on, ever more pictorial shorthands came into being, as ‘by the benefite of speedy writing, the whole body of the Lecture, and sermon might be registred’ while otherwise ‘no more remaineth after the hower passed, then so much as the frailtie of memory carieth away’.26 By the time charactery made its way into print in 1588, several other forms of shorthand were already extant, though ‘none’ of them, maintained charactery's inventor Timothie Bright, was ‘comparable’ with his own.27 As Bright also patented his own system, ensuring no one could teach, print or publish any new form of ‘character’ for the next fifteen years,28 other systems were forced underground. Edmond Willis, whose shorthand was not printed until 1618, for instance, had been using it for the previous twenty years; it was the method employed to note the sermons of Nicholas Felton between 1599 and 1602, as a surviving manuscript attests.29 By the time Willis printed his Abreviation of Writing by Character, London was crammed not so much with shorthand books as with shorthand teachers who had ‘with their Bills…be-sprinkled the posts and walls of this Citie’.30

Some shorthands never made it into print. Most, after Orthographie, whether logographic or phonetic, were reliant on new symbols, which meant that publication was expensive: the new characters needed to be carved onto special types, or engraved onto plates, or, as was the case with John Willis's Stenographie, which could be bought ‘charactered’ or ‘uncharactered’, inked in by hand on every page. So though by 1641 ‘short-hand writing’ was ‘usuall for any common Mechanick both to write and invent’, it is impossible to tell how many systems there were at any particular period, and how they related to one another.31 What can be said is that at least the following different shorthands were being discussed by name – each name representing a different ‘brand’ – in London by the 1650s: brachygraphy, brachyography, cryptography, polygraphy, radiography, semigraphy, semography, steganography, stenography, tachygraphy, zeiglography.

As Arnold Hunt in his brilliant Art of Hearing makes clear, however, texts that claim to have been taken by shorthand often contain mistakes traceable to longhand; shorthand involved longhand when that was necessary, and the shorthand-longhand distinction is not entirely useful.32 Besides, as Richard Knowles reminds us, longhand itself also remained popular for notes:33 shorthand, after all, comes after the desire to note, and is a consequence of that desire, not a cause. Oliver Heywood, writing about the 1650s, records that his wife would take, at sermons, ‘the heads and proofes fully and a considerable part of the inlargement’; she, he observes, ‘writ long-hand and not characters’, making clear that longhand might be sufficient – and that both long- and shorthand were ‘usual’ for sermon notes at the time.34 Many were committed to the shorthand cause, however. In 1634, Samuel Hartlib, in an excess of zeal, proposed sending volunteer shorthand writers to every single sermon preached in London, with the aim of preserving all of them.35

Whether notes were gathered in longhand or shorthand, or a mix, they tended to end up in longhand. Notes taken during sermons were helps towards remembering an entire sermon later, and were often rewritten at home. Margaret Hoby, for instance, went to the popular ‘Egertons sermons’ in 1600, afterwards ‘setting downe’ – writing in a permanent medium – ‘some notes I had Colected’; Gilbert Freville made a longhand commonplace book in 1604 from ‘the notes, taken…at sev[er]all sermons of Mr. Stephen Egertons preached at Black friers’, his texts extending to up to two thousand words.36 John Manningham's longhand surviving sermon records are fuller still: consisting of texts that are up to four thousand words long, they roughly match the length of the sermon itself.37 Given the habit of rewriting sermon notes at home in order to free a tablebook for reuse, to expand shorthand for other readers, or to create the fullest aide memoire, the process of note-taking in whatever form easily became (re)writing. A final, written up, sermon might well come to seem the possession of the note-taker – for its gaps had been filled by the note-taker's words, and it had been inscribed, and reinscribed, in the note-taker's hand.

Perhaps this accounts not just for the regularity with which noters then published the sermons they had gathered but for their habit of boasting about it. Edward Philips's Certaine Godly and Learned Sermons proclaim on their title‐page that they are provided ‘as they were…taken by the pen of H. Yelverton of Grayes Inne Gentleman, 1605’; William Perkins's A Cloud of Faithfull Witnesses, brags on its title‐page that it is ‘published…by Will. Crashawe, and Tho. Pierson…who heard him preach it, and wrote it from his mouth’ (1608). Publishers too, were ready to reveal that the sermons they were issuing were published against the will of the preacher; this gave purchasers the delightful frisson of acquiring something that was morally improving and, as it was not designed for them, illicit. Of Henry Smith's Sermon of the Benefite, ‘Taken by characterie’, ‘it were not the authors minde or consent that it shoulde come foorth thus’ (1590); the doctrines in Dod's The Bright Star ‘were received from his mouth, but neither penned nor perused by himselfe, nor published with his consent or knowledge’ (1603).38

Though some preachers printed their own sermons, others, who suddenly discovered their sermons in print, were outraged, publishing correctives to ‘bring this boate to land, which the owner never meant should see the shore’.39 It is often only the correctives that reveal that the earlier texts were ‘stolen’ in the first place: ‘Some (I know not who)…have presumed to printe the Meane in Mourning, altogether without true judgement, or calling me to counsell therein’ writes Playfere at the front of his revamped Pathway to Perfection (1596); in front of his new Meane in Mourning he records that ‘this sermon hath been twise printed already without my procurement or privitie any manner of way. Yea to my very great griefe and trouble’ (1596).40 Preachers who did not mind their sermons being published never reveal the theft – meaning that probably more printed sermons of the period are ‘taken’ than is known about.

What is noticeable, however, is that Playfere's correctives, like those of his fellow preachers’, are not hugely different in substance from the ‘bad’ texts that preceded them. Partly this is because preachers did not write entire texts before preaching, but spoke from notes of their own; the published ‘bad’ texts were the most complete records available of what had been preached.41 But partly this is because the substance was fairly well represented – it was the verbal texture that had been lost. What is corrected the second time round by preachers is not so much content as style, which some think of as too full of flourishes, and others as not having flourishes enough – the point being, either way, that the text does not sound ‘authorial’. Though Dod's Plaine and Familiar Exposition was first published ‘By noters hand’, explains ‘E.C.’, it is now revised by the author, and appears ‘In grave and sober modest weede, not garishly bedeckt’.42 Playfere is particularly explicit on the subject: the two previous, noted, editions of The Meane in Mourning ‘were but wooden sheathes. Or if there were any mettall in them, yet it had not an yvorie but a dudgin haft, being blunt and dull, without any point or edge’, an explanation that illustrates, in its very phrasing, the importance to him of the striking ‘literary’ image his sermons had lost.43

Naturally, Londoners, habituated to noting by education and church, responded not only to preachers but to other speakers by inscribing them: public utterance tended to lead to text. Note-takers filled parliament, relying on tablebooks to create records they would afterwards write up – William Holt, on 13 March 1607, attended parliament with ‘tables in his hand, and was seen to write diligently’; Sir Francis Bacon, reporting on a conference he had attended about Scotland, ‘professeth to omit some answers by reason that his tables failed him’.44

It will come as no surprise that spectators went to playhouses, too, with notebooks in their hands. Often, like the congregation show-offs, they were interested in waving their books around while collecting tiny snippets of text – which may explain why playwrights of the period so often wrote in sententiae and instantly quotable passages (‘soundbites’ in today's parlance). ‘Gulls’ in the theatre are described who ‘will not let a merriment slip, but they will trusse it up for their owne provision’:45 they gather jokes from plays to repeat later as their own. Lawyers, too, in their most carefully designed choleric rants, were said to be making use of ‘shreds and scraps dropt from some Stage-Poet, at the Globe or Cock-pit, which they have carefully bookt up’.46 Many went to plays to gather the newest word into their tables, as Shakespeare parodies, when Holofernes in Love's Labour's Lost uses the word ‘peregrinat’ and the fascinated Nathaniel ‘Draw[s] out his Table-booke’ to record it (TLN 1752–5).47 What was collected at plays might include staging details, as well as dialogue, for these could function, like a theatre programme today, as a token or memento of performance. The playwright Cyril Tourneur writes about a man who saw an entertainment without writing equipment: ‘Many…pretty Figures there were expressing the meaning of these Maskers’, mourns the man, ‘which, for lack of a note booke, are suddainlie slipt out of my memorie’.48 But playwright Thomas Dekker writes of plays that were comprehensively gathered. Describing the accession of King James as a play, he declares: ‘it were able to fill a hundred paire of writing-tables with notes, but to see the parts plaid…on the stage of this new-found world.’49

There was, then, nothing covert or hidden about noters in the audience; confident playwrights, like confident preachers, assumed the practice of noting reflected the worth of the play. Fletcher and Massinger, for instance

Playwrights did, however, fear malicious noters in a way that preachers did not. Several refer to spectators who gather passages because they dislike them, or intend to misinterpret them later out of context: ‘if there bee any lurking amongst you in corners, with Table bookes…to feede his ——— mallice on, let them claspe them up, and slinke away, or stay and be converted’ suggests Beaumont.51 Cordatus, spokesman for Ben Jonson, defensively turns upon the audience members he calls ‘decipherers’: ‘(where e're they sit conceald) let them know, the Authour defies them, and their writing-Tables’.52 As noted passages, favourable and otherwise, would also have to be retranscribed at home to clear tablebooks, extant theatrical commonplace books are generally in longhand, though that reveals nothing about the gathering process.53

Early performances of Hamlet were, it seems, attended by noters, as a surviving passage suggests. In 1623 William Basse republished his popular book A Helpe to Discourse. Designed for the conversationally inadequate, the book provided a series of questions or riddles with their ideal answers. One of its new ‘ideal’ exchanges includes the following question (Q) and the perfect answer for it (A):

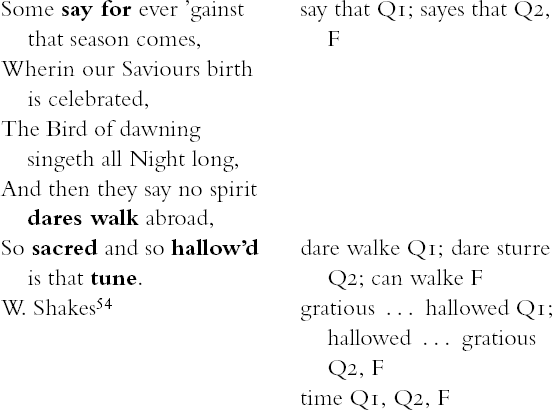

Basse's passage differs verbally from all three printed Hamlet editions (they also all differ from one another, though the lines are spoken by the putative actor-pirate Marcellus); Basse also neglects to print altogether a couple of lines found, in some form, in all three texts: ‘The nights are wholsome, then no plannets strike, / No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charme’ (Q2). Most telling, though, is the fact that Basse's version declares that it is the bird's ‘sacred and hallow'd…tune’ that prevents spirits walking, rather than the ‘hallowed and gracious…time’, Christmas, that keeps the spirits at bay. As ‘tune’ and ‘time’ are unlikely to be misheard, but are quite easy, through minim error, to be misread, Basse is almost certainly printing notes originally written at the theatre (the error is unlikely to be compositorial, as it is retained in subsequent reprintings of the book).55 If so, his notes may have been in longhand, as ‘un’/‘im’ is an alphabetical error.

People did, though, also take notes using shorthand in the theatre – particularly when they were trying to capture a whole text. In a passage published in 1615, George Buc, Master of the Revels since 1610 (and granted its reversion in 1603), recorded of brachygraphy that ‘by the means and helpe therof (they which know it) can readily take a Sermon, Oration, Play, or any long speech, as they are spoken, dictated, acted, & uttered in the instant’.56 George Buc's profession will have made him particularly conscious of the way plays (and he specifies a ‘play’ rather than a ‘passage’ of play) were ‘taken’ in the theatre; he may too have seen the print consequences of brachygraphy, as, from 1606 onwards, he had been the licenser of playbooks for publication. He is joined by playwright Thomas Heywood who, in 1637, published a prologue that puffed the revival of his play If You Know Not Me, You Know Nobody. Heywood reminded the spectators that the version of the play that they had bought – first published in 1605 – had come about disingenuously: ‘some’, he charged, ‘by Stenography drew / The plot: put it in print: (scarce one word trew:)’.57 Heywood's new prologue assumes an audience that ‘knows’ that ‘stealing’ plays – or, it is here suggested, their scenarios, to be filled with ‘untrue’ text later – through shorthand was possible in 1605; a ‘noter’ himself, as this article has shown, Heywood is likely to be particularly conscious of other note-takers. He had, in 1608, recorded that several of his plays had ‘(unknown to me, and without any of my direction) accidentally come into the Printers handes,…(coppied onely by the eare)’:58 these were plays taken, as sermons had been, against their author's will and, as Heywood emphasizes, not from any kind of written text, but from heard performance.

Other playwrights articulated in more roundabout ways their fear that what started as (shorthand) notes might end up as illegitimate printed text. John Webster writes a dialogue exchange concerning note-taking at court in The Devils Law-Case. ‘You must take speciall care, that you let in / No Brachigraphy men, to take notes’, says Sanitonella, explaining that the result will be ‘scurvy pamphlets, and lewd Ballets’; his notion was that shorthand led to distasteful publication.59

Printed plays, however, do not habitually articulate the varying processes that brought them to the press, as sermons do, so it is harder to identify noted texts amongst them. This is partly because a company, rather than a playwright, was likely to ‘own’ a play manuscript – meaning that playbooks generally reached the press without authorial paratexts; they were, as one 1607 writer put it, usually ‘published without Inscriptions unto particular Patrons (contrary to Custome in divulging other Bookes)’.60 Nevertheless ‘corrected’ playtexts were sometimes released, presumably by companies, in the wake of errant ones: Romeo and Juliet Q2 explains on its title‐page that it is ‘newly corrected, augmented, and amended’ (1599), thus casting aspersions on the previous text – a practice that also worked well as advertising: I Henry IV used it even though simply reprinting the earlier edition. Such printed title‐pages are reminiscent of that for Henry Smith's rectified [The] Affinitie of the Faithfull, ‘Nowe the second time Imprinted, corrected, and augmented’ (1591). Hamlet Q2 is similarly ‘Newly imprinted and enlarg'd to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect Copy’ (1604), strongly suggesting that Hamlet Q1 is defective, and not directly authorial. As to why a company might release a correct text when an incorrect one was doing the rounds – the answer is probably pragmatic: once a text was being sold anyway, it might as well be sold in its most accurate form. Besides, as playhouses were also sites where playbooks (and sermons) were offered for sale, there was some logic in being able to market, to the sitting audience, texts that advertised and promoted the theatre.61

The vocabulary used by sermons for illegitimate texts is matched by that adopted by some playtexts – suggesting a similar process is responsible for both. So sermons printed poorly from notes are often depicted as wounded bodies: they are ‘maimed copie[s]’, texts printed ‘with intollerable mutilations’, ‘lame and unjoynted’ or, taking the metaphor further, with ‘whole lims cut off at once’.62 Playtexts employ the same language. Beaumont's ‘Philaster, and Arethusa’ had been ‘mained [sic] and deformed’, and then ‘laine… long a bleeding, by reason of some dangerous and gaping wounds,…in the first Impression’.63 Heminges and Condell, introducing Shakespeare's Folio, even adopt the ‘limbless’ metaphor when describing the earlier quartos (including Hamlet Q1, though they appear to extend their blame to all previous publications): ‘(before) you were abus'd with…copies, maimed, and deformed by the frauds and stealthes of injurious impostors,…those, are now offer'd to your view cur'd, and perfect of their limbes’.64 As this vocabulary makes clear, the errant sermons and plays are damaged (‘wounded’) versions of the whole works with which they are compared – they are, then, not described as preparatory drafts by authors, or direct transcriptions, but poor descendants of better, complete texts.

How such mangled texts reached the printer is also much more clearly addressed in sermons than in plays – though, again, shared vocabulary gestures towards a shared process. John White was forced into print when he learned his sermons were in danger of ‘stealing out at a back dore’, his comment playing on the double meaning of ‘stealing’ – surreptitiously creeping and being pilfered.65 Later in time, friends of the Archbishop of Canterbury were outspoken on the subject: they fronted his sermons with a warning against versions published ‘surreptitiously’ and explained their origins:

Whereas several Sermons of His Grace JOHN late Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, Imperfectly taken from Him in Short-hand, may be surreptitiously Printed: This is to give Notice, That there is nothing of His Grace's design'd for the Press at present.66

It is that same vocabulary that is used, most famously, for Shakespeare's First Folio. There Heminges and Condell compare the ‘cured’ texts they are printing with the ‘diverse stolne, and surreptitious copies’ that have preceded them.67 Though this passage is still variously interpreted – Heminges and Condell are at the very least exaggerating for publication purposes, as they actually use some of the preceding quartos as copy – they are nevertheless assuming a process of ‘stealing’ plays with which the reader will identify. Humphrey Mosley, the publisher, does likewise. In his edition of Beaumont and Fletcher's Comedies and Tragedies, he draws a distinction between the ‘Spurious or impos'd’ preceding texts and what he is now printing, ‘Originalls’, which ‘I had…from…the Authours themselves’.68 Other plays claim to have been printed in a rush to forestall the publication of poor-quality stolen texts. The 1655 tragedy Imperiale was put in print ‘chiefely to prevent a surreptitious publication intended from an erroneous Copy’ – ‘erroneous’ again suggesting lack of authority in the circulating text.69 The 1620 comedy The Merry Milkmaids, meanwhile, had not been intended for a readership at all. ‘Had not false Copies travail'd abroad’, explains its introduction, ‘this had kept in’; the play itself had been designed ‘more for the Eye, then the Eare; lesse for the Hand, then eyther’, the ‘hand’ berated here seemingly, as with sermons, that of the person who rendered performance into text.70

Theatres and churches were both sites of ‘entertainment’ for which entrance fees could be charged. Huygens describes a 1650s church in Covent Garden ‘divided into boxes, just like a place where comedies are performed’ for which ‘Before one enters…one must pay a fee according to the position of the seat’, and John Hurlebutt was given the right to charge entrance fees to Paul's Cross ‘due…by use and ancient Custome’. Thus it would not be surprising if the noting that both encouraged led to publication too.71 A congregation/audience, attending an entertainment it had paid for, may have felt it had purchased its experience, and had a right to ‘take’ it.

Given the longhand and shorthand notes taken in churches and theatres, seemingly in similar fashion and for similar reasons, it is worth exploring whether Hamlet Q1 might have its origins in a ‘noted’ text.

Note traces in Hamlet Q1

How can ‘note-taking’ be recognized in a printed text? Scholars who look for a particular form of shorthand in Shakespeare's plays are often unconvincing: they have to spot shorthand behind a printed, longhand word, and become loyal to a single brand of shorthand, ignoring the fact that longhand, or shorthands that no longer exist, may have been used by the audience. So this section will eschew shorthand itself, though its presence in a noted text is likely. Instead, it will look for the techniques taught around shorthand: ‘swift writing’. These include methods for taking orations verbatim, and methods for taking them by contraction or summary. Comparison will, again, be made with ‘noted’ sermons. Can ‘swift writing’ be found in Hamlet Q1?

For catching words ‘swiftly’ as they were spoken ‘verbatim’, every manual advised noting by synonyms. Indeed, some early shorthand forms, like charactery and brachygraphy, depended on synonyms: in those systems, the noter learned a general symbol that stood for a noun – say, ‘air’ – and then placed a letter by that symbol to describe what variety it took: so ‘air’ plus ‘b’ would be ‘breath’, and ‘air’ plus ‘m’ would be ‘mist’. Alternatively, as Bales put it, one was simply to ‘take such a word in your [brachygraphy] Table as your selfe shall thinke to come…neere unto it …which words of like sense are called Synonimies’.72 Other, later, systems, which were phonetic, and thus more directly related to longhand, still encouraged synonyms. W. Folkingham, for instance, thought there was ‘good purpose’ in substituting short words for long, recommending that instead of ‘assistance, renowne, unadvised, communication’ the noter opt for the shorter words ‘ayde, fame, rash, talke’.73

Hamlet Q1 is known for its synonyms; commentators are often puzzled to see one word quite needlessly replaced by another. Q2/F's ‘did sometimes march’ is Q1's ‘did sometimes / Walke’, Q2/F's ‘this marvile to you’ is Q1's ‘this wonder to you’, Q2/F's ‘a clout uppon that head’ is Q1's ‘a kercher on that head’. Sometimes almost every word is matched by a synonym, as when Q2/F's ‘the first rowe of the pious chanson / will showe you more’ is Q1's ‘the first verse of the godly Ballet / Wil tel you all’. Synonyms, necessary for charactery and brachygraphy, and recommended by subsequent systems, would explain this habit of replacing words, and would explain, too, why the poetic flourishes of Q2/F are often reduced or simplified by synonyms – as when Q2/F's ‘My pulse, as yours, doth temperatly keepe time’ is, in Q1, ‘my pulse doth beate like yours’. For an actor-pirate, trained to remember a text by sound and rhythm, a synonym is less obvious than the correct word; for a note-taker, however, synonyms are a habit of thought long learned and regularly advised in swift-writing systems.

Another aid to writing ‘verbatim’ was to note only so much of a word as was necessary to recall the whole. Bales suggests, ‘take the two first letters of everie name, and so commit the rest to memorie’.74 Again, one of the striking features of Hamlet Q1 is that, aside from entirely different names (‘Corambis’ and ‘Montano’ are covered in the conclusion to this article), many of its names recall the ones in Q2/F but are slightly different – Q2/F's Cornelius is Cornelia, its Voltemand is Voltemar, its Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Rossencraft and Guilderstone; where, in Q2/F ‘Sceneca cannot be too heavy, nor Plautus too light’, in Q1 it is ‘Plato’ who cannot be ‘too light’, despite the fact that Plato was not a playwright. Of course, names at the time admitted of fluid spellings. Nevertheless, if an actor-pirate was playing Voltemand, it is surprising that, in addition to misrecalling his entrance in the last scene, he also cannot remember his name.

Another trick to help with verbatim writing was to ‘rest’ while rhyme was spoken. John Willis, in 1602, reminded the noter that he could omit ‘the ende of a line answering in sound the end of some other line’.75 That was because the rhyme itself would prompt and recall the other, matching, half. Again, Hamlet Q1 seems to bear traces of this: it is striking how often in that text one half of a rhyming couplet is presented with relative accuracy, while the other half differs entirely. Examples include the King's rhyming couplet that in Q2/F describes his inability to pray: as his guilt remains unexpiated, only the sound, not the content, of his words can reach heaven.

In Q1, however, the King is unable to pray because God has taken against him:

The rhyme, entirely against the tenor of the rest of the King's prayer, is preceded by the only semi-accurate line of the whole supplication (‘My wordes fly up …’); it appears to have been collected in a different fashion from its surrounding dialogue, and rules for noting might explain why. Likewise Hamlet's lines in Q2/F refer to the Herculean task of restraining Laertes (while perhaps metatheatrically gesturing towards the Globe, the sign of which was Hercules shouldering the world):

In Q1 these are recorded as:

As Laertes is already standing, and as it is Hamlet who then sweeps out, ‘stand away’ seems to have been brought about to fit the rhyme rather than for its meaning. (The capture of the second line here may reflect the fact that only the rhyme revealed with certainty that a couplet was being spoken.)

Note-taking, too, is suggested by aural errors in Hamlet Q1, for it would be surprising if an actor-pirate, shrewd enough about sense to recall synonyms, is also ignorant enough about sense to recall entirely wrong words that sound similar – whereas, as Willis warns, a noter might easily ‘write one word instead of another, & take one word for another’, particularly as it can be hard to think while capturing text verbatim.76 Obvious aural errors include the fact that ‘Norway’ who in Q2/F is ‘impotent and bedred’, is in Q1 ‘impudent / And bed-rid’; in Q2/F ‘The Gloworme shewes the matine to be neere’, while in Q1 ‘the Glo-worme shewes the Martin To be neere’; in Q2/F ‘Who this had seene, with tongue in venom steept’, while in Q1 ‘Who this had seene with tongue invenom'd speech’. Amongst further examples that might be aural error are Q2/F's ‘we did thinke it writ downe in our dutie / To let you knowe of it’ which in Q1 is ‘wee did thinke it right done, / In our dutie to let you know it’; J. P. Collier, however, himself a shorthand writer, pointed out that ‘rt dn’ would be alphabetic shorthand for both – it was, indeed, this instance that led him to conclude that Hamlet Q1 was a shorthand text.77

Sometimes in Hamlet Q1 there seem to be traces of memorial corruption. That, too, can be ascribed to note-taking, however, for when a speaker was ‘very swift of deliverie’, the noter was advised to ‘write only the…Wordes essentiall to the speech delivered, reserving a space for the rest…to be supplied with Penne immediately after the speech is ended’.78 There is no suggestion, then, that noting precludes memory – and, indeed, John Willis, as well as inventing stenography, also wrote a text on The Art of Memory (1621); for him stenography was memorialization in note form.

Often, in Hamlet Q1, a correct word is in the correct place in the play – but its meaning is different, as though it has been recorded ‘verbatim’, but the space surrounding it has been completed using inadequate memory later. Thus, there is the moment where ‘course’ in Q2/F means ‘corpse’, while in Q1 it means ‘route’ or ‘movement forward’, suggesting the word was marooned and a context has later been invented to house it:

Likewise, there is the section of Q2/F in which ‘grave’ means ‘serious’, and its matching section in Q1, where ‘grave’ remains in situ though context now renders it ‘sepulchre’ (here it is equally possible, of course, that the word ‘grave’ was ‘correctly’ guessed at through rhyme):

In the famously muddled text of ‘To be or not to be’, meanwhile, though in Q2/F Hamlet fears ‘The undiscover'd country, from whose borne [frontier/terminus] / No travailer returnes’; in Hamlet Q1 he fears the moment ‘when wee awake, / And borne [carried] before an everlasting Judge’. As these and other instances suggest, ‘the judicious Wryter’ (the noter) has made ‘what hee had over-taken, to coheare, the best hee could’.79 While an actor is likely to remember a word because he remembers its context, rather than entirely separately from it, a writer might easily find him or herself with a tablebook containing a stranded word without its surrounding logic.

Books of shorthand, having devoted some pages to teaching the ‘verbatim’ capture of words, then teach a contrary skill. They show how meaning may be preserved when none of the original words are kept. ‘For, The great triangled Iland in the West’ suggests Willis, ‘write England.’80 Often, they suggest that a lengthy idea can be reduced to its quintessential meaning or ‘epitome’ – which can have a particularly devastating effect on poetry, as one of Willis's contractions illustrates. He starts with the full text, supplying a passage from Spenser's Faerie Queene:

He suggests it can be ‘Contracted thus: At last the Sunne arose’.81 Willis's expectation that a ‘noter’ will need to contract verse anticipates, of course, a listener hearing a lot of poetry (a reader can copy verse verbatim). A play is the most obvious event at which noters are deluged with verse.

At various points, Hamlet Q1 appears to show contraction, its poetic lists being often reduced to bland summaries of their contexts. In Q2/F Gertrude describes how Ophelia came to the willow with ‘fantastique garlands’ consisting of:

In that same passage in Hamlet Q1 she explains how Ofelia came ‘Having made a garland of sundry sortes of floures’. Here an actor might be expected to recall the elongated ‘long Purples’, the bawdy ‘grosser name’, or the prescient ‘dead mens fingers’. But a summarizer, using the rules of contraction, reduces the text irrespective of verbal texture. Of the same kind is the section that in Q2/F reads:

In Q1 this reads, ‘Why these Players here draw water from eyes: / For Hecuba’. These Q2/F lines in particular, might be expected to stick in the mind of an actor, for they are about the trade of playing; for a contracting noter, however, they breezily summarize the sense, though not the emotions, of the discourse.

Other passages that bespeak a noter are stage directions. Well-known unique and elaborate stage directions in Q1 supply or record visually striking details of the production – ‘Enter the ghost in his night gowne’, ‘Enter Ofelia playing on a Lute, and her haire downe singing’. These seem to preserve the experience of watching Hamlet, at least as much as they tell actors what to do. Indeed, so conscious is the Hamlet Q1 text of visual happenings on stage that actions sometimes end up recorded as part of the dialogue: Hamlet says to his mother in the closet that he'll talk to her ‘but first weele make all safe’; a Q1 only line, this seems to indicate that Hamlet checks and perhaps locks the door. Action, written down, seems also to be visible when the Queen reports, using the historic present, how Hamlet ‘throwes and tosses me about’, a recollection of the lurid closet scene we have just seen, and also unique to Q1.

Even the play's frequent mislineation is more easily traced to a noter than an actor. A noter trying to capture rapid spoken text, would probably take down the words as spoken, without recording line-division at all; an actor, whose skill relied on his choice of ‘pointing’ using correct pronunciation and emphases, is likely to have been conscious of line endings – he needed to observe, particularly, when they were enjambed – which would have been an aid to memorization.

How, though, to explain the larger oddities of Hamlet Q1: the fact that the order of Hamlet Q1 is different from the order of Q2/F? That might, of course, reflect the version of the play that Q1 records. Yet significant reordering is a feature of noted sermons, explained by the fact that the noter wants to preserve as much text as possible, but has not always recorded how it connects together. ‘Although the Pen-man’ of Philips's Certaine Godly and Learned Sermons ‘in setting downe these Sermons, have not precisely kept the divisions of them…as placing more in some one Sermon then was uttered at one time, and lesse in some other: yet in the whole…thou shalt find nothing wanting’.82

Some of the transposed sections in Hamlet Q1 seem to have been resituated with what might be a noter's logic. Material of a similar kind tends to be pooled together. Hamlet's conversation with Ophelia about the jig-maker and the hobby-horse, for instance, is not spoken before the dumbshow (as in Q2/F), but is incorporated into their similar, later conversation about ‘the puppets dallying’ after the entry of Lucianus. Hamlet's comparison of Rosencrantz to a sponge, which in Q2/F is in 4.2, in Q1 follows from his equivalent lecture to Guildenstern about the recorder. A similar explanation may even account for the play's largest transposition. In Q2/F, the ‘to be or not to be’ speech and its subsequent nunnery scene occur after the arrival of the players at court; in Q1 they are placed a day earlier, just before the ‘fishmonger’ scene. The problem may arise from an attempt to group like with like again. In Q2/F Hamlet enters the stage for the ‘fishmonger’ scene with a book in his hands; later, Ophelia is ‘loosed’ to Hamlet with a book in her hands for ‘to be or not to be’ and nunnery scene. Q1, however, introduces Hamlet with his book, immediately flanked by Ophelia and her book; matching book with book may be the cause for the scene's new placement – perhaps prompted by the fact that Polonius, in all texts, has said that he will go with Ophelia ‘to the king’, even though in Q2/F he then actually goes to the court by himself. Immediate fulfilment of what Polonius had promised, by means of two bookish tragic heroes, may be the cause for this transposition.

Additions, too, were usual in noted texts, heard of in sermons both when the noter boasts that he or she will not need to have recourse to them – ‘I have added nothing of mine owne’; ‘what is…by mee published under his name, shall not be…made up with additions, and alterations of my owne’ – and in sermons when the noter feels addition is appropriate: ‘we let these Sermons passe forth as they were delivered by himselfe, in publicke, without taking that libertie of adding or detracting, which, perhaps, some would have thought meete’.83 Yet the comparison of sermons to patchworks reveals that passages between notes were often the noter's creation: ‘coppies of this Sermon,…were…(patched as it seemeth) out of some borrowed notes’; ‘in some places the minde of the Author [is] obscured, in other some the sentences [are] unskilfully patched together’.84 Hamlet Q1 can most obviously be seen to be a series of notes stitched together when it uses poetic lines from other plays to solder its gaps. Laertes in Hamlet Q1 says ‘Revenge it is must yeeld this heart releefe’, which picks up Hieronimo's lines in The Spanish Tragedy ‘in revenge my hart would finde releefe’;85 Corambis’ wise saw in Q1, ‘Such men often prove, / Great in their wordes, but little in their love’, repeats Viola's sentiment in Twelfth Night, ‘We men’ who ‘Prove / much in our vowes, but little in our love’ (TLN 1005–7); even the oft-derided ‘To be, or not to be, I there's the point’ may echo a crucial line in Othello, Iago's ‘I, there's the point’ (TLN 1855). A noter who has records of several productions has reason to be conscious of their similarities; an actor may have various productions in his head – but needs to observe their differences to avoid switching the performance to the wrong play.

Other Hamlet Q1 additions consist of the same line repeated over and over again. ‘To a nunnery go’, for instance, becomes something of a refrain in the nunnery scene, which speaks to its power as a phrase, but which again argues against an actor-pirate, whose consciousness of ‘parts’ is likely to have mitigated against a text that would yield Ofelia a ‘virtually unplayable’ part like this:86

Larger additions in Hamlet Q1 simplify the play and are partly responsible for its short length. In the most major addition, Horatio relates to the Queen a letter he has received telling of Hamlet's escape from the ship taking him to England. The Queen then declares her disillusionment with the King and loyalty to Hamlet. This addition compresses 4.6 and 5.2, dispenses with some additional characters, and makes the Queen, who ‘was the character that lent itself most readily to…simplification with the least loss of subtlety’, less complex and more sympathetic.87 This section, then, may have been designed; on the other hand, it may have been created to fill a gap, as the Queen then does nothing to substantiate her new allegiances, and the play returns to the plot of Q2/F again.

Finally, Hamlet Q1 is filled with gaps, in which sections are so clearly missing that ‘some passages in Q1 make sense only to someone familiar with Q2 or F, a clear indication that Q1 was derived from a longer version’.88 Examples include the moment when Horatio says ‘Heere my lord’ though Hamlet hasn't called for him; the moment when ‘the flood’ is seen to ‘beckle [beetle?] ore his bace into the sea’ (because the line about ‘the dreadful summit of the cliff’ is missing); the moment when Hamlet forces the king to drink the wine, ‘here lies thy union here’, though the king has never thrown a union into the cup. Gaps, it will hardly be surprising to discover, are features of noted sermons. Smith's Benefite had been ‘abused in Printing, as it were with whole lims cut off at once, and cleane left out’; and Rich recorded how regularly noters ‘in the midst of discourse, when the tongue of the Speaker hath out-run the pen of the Writer…strike saile and lie becalm'd, not knowing where to stay, nor which way to goe’.89 As a whole, then, what Gouge said about troubles in the worst recorded sermons could also be said about some sections of Hamlet Q1:

Many have beene much wronged…by the Short-writers omissions, additions, mis-placings, mistakings. If severall Workes of one and the same Author (but some published by himselfe, and others by an Exceptor) be compared together, they will easily be found in matter and manner as different, as Works of different Authors.90

What is extraordinary about Hamlet Q1, however, is not that it is universally ‘bad’, but that it is not. Hamlet Q1 consists of relatively accurate ‘verbatim’ noting early on, and relatively inaccurate generalized noting later – with the odd ‘verbatim’ passage again. It is as though the noter is sharp and obtuse, fast and slow, led by the word and led by the meaning. But explanations for that, too, can be supplied, first by looking at performers, and second by looking at noting habits.

Firstly, the clarity of the performer affected the quality of the notes. As Willis presents the problem in dialogue:

Preachers whose texts had been inadequately represented, often attributed the problem to their own fluency. Egerton maintains that ‘the swiftest hand commeth often short of the slowest tongue’, though ‘often’ allows for the remote possibility that some writers may keep up. Nevertheless, he stresses his point by explaining how his own words have been imperfectly ‘penned’ despite the fact that he is ‘constrained thorough the straightnes of my breast, & difficulty of breathing, to speake more laysurely then most men doe’.92 ‘R.C.’, a noter, excuses his own inadequacies by asking ‘what hand or memorie can follow so fast the fluent speech of an eloquent Preacher, as to set downe all in the same forme and elegancie wherein it is delivered?’93

What that actually meant was that a speaker would impact the accuracy of the noter – always bearing in mind that ambient and background noise might also affect his ability to be heard. James I, for instance, slowed one of his speeches to parliament: ‘because I see many writing and noting I will hold you a little longer by speaking the more distinctly for fear of mistaking’; Perkins the preacher ‘observed his auditors, and so spake, as a diligent Barve [sic: ‘Brave’] might write verbatim al that was spoken’.94 Some players will, in their natures, and some by choice, have spoken more slowly and distinctly than others. At least one reason why some speeches, and some characters – in order of accuracy, Lucianus, Prologue, ‘Voltemar’, Marcellus, Barnado, Ghost – are more clearly captured than others may be that the speakers themselves were louder or clearer.

Noting habits, however, also affected the quality of the record. The swifter the hand, the more it could take, obviously. Cupper's sermons were ‘mangeled…according to the slow hand…of him that tooke them’; Sabine Staresmore, the noter of Ainsworth's sermons, writes ‘so farr as my slow hand could extend to compasse’ explaining ‘the fullnes of his words I professe not to report’.95

There was, however, an obvious solution to the problem of slow noters, and troubled hearing: more notes. Noters, for this reason, often combined their various texts. One reporter of a parliamentary speech, for instance, described the way he sought further notes to improve his own: ‘I did diligently employ my tables, and made use of the like collection of two gentlemen of the lower house who had better brains and swifter pens than I.’96 In this instance, one putatively ‘slow’ and two putatively ‘fast’ texts were combined, though each had been separately penned. A similar combination is projected by Crashaw when he prints a plea for more good accounts of Perkins's sermons. He requests that:

all who have any perfect Coppies of such as are in my owne handes, that they would either helpe me with theirs, or rather take mine to helpe them. That by our joynt powers and our forces layd together: the walles of this worthy building, may goe up the fairer & the faster.97

Sometimes, alternately, groups of people seem to have arranged to attend a sermon together and combine notes afterwards. Symon Presse dedicates his 1596 sermon ‘To his loving parishioners Mr. F. Cooke, R. Johnson, W. Walton, R. Knight, J. Gyllyver, & R. Slygh’, because the six men have conjointly taken such ‘paines in conferring together’, and ‘penning…to make my simple skill liked’.98 If a group attended together, intending to share their work later, they could distribute the task of note-taking between them, either noting in relay, or divvying up features like structure and content according to their skills. In an intense version of this, orphans in 1690s Germany were told to transcribe 10–12 words of a sermon in turn; the whole was then reconstructed from their notes later.99

If Hamlet Q1 is a text combined from the notes of two or more people, then the reason for its ‘good’ earlier section, and poor later sections is explained: they bespeak two or more separate noters, the early ‘good’ one being more given to verbatim methods of copying, and perhaps using good longhand or phonetic shorthand, the later, less good one (or more) tending towards contraction and epitome, and perhaps reliant on less good longhand or pictorial shorthand. The sudden good speeches later would then be traceable either to actors who spoke more clearly, or to a noter supplying freestanding verbatim ‘passages’ to be combined with someone else's ‘whole’ text later. There are certainly reasons for thinking Hamlet Q1 a combination of different people's work, rather than a text made by one person. Some sections are ‘right’, then ‘wrong’, and then ‘right’ again, as when the internal dumbshow consists of ‘the King and the Queene’, while the play it flanks calls the same people ‘the Duke and Dutchesse’, though in that play Lucianus is still described as ‘nephew to the King’. A combined text would explain how this, and similar right/wrong moments, came about – not least because, as in Q2 ‘Gonzago is the Duke's name’, a version of the play visited by one of the noters might have had a Duke and Duchess instead of a King and Queen.

It should also be remembered that amongst the noters of a combined text just might be a ‘memorizer’. Willis, in his book on memory, writes of ‘divers unlettered persons’ who can ‘retaine much more then the…Penman’,100 and a few of Hamlet Q1's signs of memory may relate to such a person – though too many features of Hamlet Q1 recall the note-taking process to explain the whole text as the product of audience-memory. Jesús Tronch-Pérez, for instance, writes a thoughtful article in which he examines the relationship between the suspect ‘memorized’ text of Lope de Vega's La Dama Boba and the actual text, comparing it to the relationship between Hamlet Q1 and Q2/F; he finds Hamlet Q1 oddly lacking in the signs of memory that typify La Dama Boba.101

Combined texts naturally required an ‘amender’ to massage the various scripts together. The printers of one 1623 sermon, for instance, are amenders: having received a text ‘miserably written’, they did what they could to make sense of it: ‘Being loth, to leave out any sentence, or piece of a sentence, which we could make English of, we put some words downe at a venture.’102 More often amenders were fans of the original text, and tried to create as accurate a representation of it as possible. Rollock's 1619 sermons were gathered by Sir William Scott of Ely ‘from the handes of SCHOLLERS, that wrote them: and by your exspenses they were written over and over againe: without you they had never beene revised and corrected: without you they had not beene made meet for the PRESSE’; John Preston's 1629 sermons, taken from his mouth, are then ‘prepared’ by those ‘that had the Coppies’; others who possess notes are asked not to ‘be hastie…to publish them, till we, whom the Author put in trust, have perused them’.103

An ‘amender’ has long been imagined for Hamlet Q1, usually denigrated by the term ‘hack’ or ‘inferior poet’. And, as Q1 is a play rather than a sermon, such a person will have been able to visit the theatre more than once, though the fact that there were no play runs in the period, added to the level of corruption in Q1, may suggest he/she did not attend many times. Nevertheless, Stephen Urkowitz, as part of a different argument, draws attention to the moment in Hamlet Q1 where two questions and two replies seem to have become confused:

He suggests that ‘how fare you’ is supposed to be followed by ‘Yfaith the Camelions dish’, and ‘shall we have a play’ should be followed by ‘I [‘aye’] father’.104 An amended text that was something of a palimpsest, with additional moments squeezed in as they were heard, might result in difficulties of this kind – though ‘combination’ without revisiting the theatre might produce similar results.

On some occasions, the printed play of Hamlet Q1 may even gesture towards its method of construction. It has, as is often pointed out, a few sections specifically highlighted by inverted commas – for instance, Corambis’ wise saws:

These inverted commas have been identified as markers of sententiae, drawing the reader's attention to passages primed for extraction into commonplace books. Thus Hamlet Q1, in published form, has been said to proclaim itself, through layout, the first ‘literary’ drama.105 This is entirely possible. It is equally likely, however, that the lines are marked as coming from commonplacing, showing not what a reader should do, but what a noter did. If this is the case, they may illustrate a section supplied by a different noter, or from a separate source, like the passage in Erasmus’ Seven Dialogues (1606) which ‘followeth after this marke *’ because it is ‘not in Erasmus’.106 Alternatively, the marks may witness a passage that an amender, revisiting the theatre, observed had been cut. In sermons, inverted commas often signify the least important passages: those not spoken during the preaching – ‘I was forced [while preaching] to cut off here and there part of what I had penned: which…I here present…distinguished from the rest with this note (,,) against the lines.’107 In the later history of the Hamlet text, too, inverted commas signal cuts as they do in playbooks throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the 1676 edition explaining:

THis Play being too long to be conveniently Acted, such places as might be least prejudicial to the Plot or Sense, are left out upon the Stage: but that we may no way wrong the incomparable Author, are here inserted according to the Original Copy with this Mark ”108

And the lines it chooses for omission? They include:

It is possible, then, that the lines in inverted commas are not the most important sections of play, but the least. Whatever is the case, the passages marked by inverted commas in Hamlet Q1 reveal some sections to be ‘different’, but whether that is because of reading habits, or because of gathering habits, depends on who is preparing the text – and what the text is.

One way in which Hamlet Q1 seems to flirt with the very idea of noters is in one if its unique passages. In Q1, Hamlet, having complained about the clown who speaks more than is set down for him, illustrates how predictable the clown's ‘extemporized’ jokes actually are:

These are jests – actually catchphrases – so obvious that people record them in tablebooks not during but in advance of performance. ‘Sly’ does something similar in the Induction to The Malcontent, when he explains that he has ‘seene this play often…I have most of the jeasts heere in my table-booke’.110 Maybe this passage is Shakespearian and ironic: the only ‘clown’ who brings these bad jokes into the play is Hamlet himself. Maybe this is an actor's interpolation designed to level further insults at an irritatingly unoriginal ‘improviser’. But perhaps this is a reference to the process that brought Hamlet Q1 about. The very jests said to be unfit for a serious play (such as Hamlet), and to belong only to tablebooks, enter here into the Hamlet text – showing how lines from tablebooks can indeed, with the aid of a noter, become passages of plays.

Why Publish Notes?

If Hamlet Q1 is a noted text, however, its pathway to the press has to be explained. Why would a noter or noters choose to publish private records – and why might a publisher accept them? Sermons, again, suggest answers to both questions.

There were several self-serving reasons for giving noted texts to the press. One was for the money; it was the noter, rather than the preacher/playwright, who would receive payment. Egerton maintains that ‘hungrie Schollers and preposterous noters of Sermons’ publish noted texts ‘beguiled with hope of gaine’, and bemoans the quest for ‘filthy lucre’ that brought his sermons to print, while William Crashaw wishes that ‘men would not be so hastie…to commend to the world, their unperfect notes, upon a base desire of a little gaine’.111 If money was the goal of printing Hamlet Q1, of course, then, provided the whole work was good enough to sell, it had served its purpose.

Printing notes also enabled the noter to see ‘his’ words published. John Winston, a noter, disingenuously confesses to having ‘nothing of mine owne of any worth whereby to testifie my unfained thankefulness’, explaining that ‘I have borrowed of others for this purpose, and withal annexed my hand-writing.’112 That urge to reach print, even without anything to say, could lead noters to add traces of themselves into the noted text. Thomas Taylor criticizes those scribes who ‘make the grounds of the authors serve their owne discourses’; and the preacher William Gouge maintains that ‘some’ had ‘attempted in the Authors name to publish their owne notes’.113 Noters, in these instances, obtrude to bear witness to their hand, or to mingle their words with their hero's. If Hamlet Q1 passed through the hands of a noter with ‘authorial’ leanings, it might record the creativity of its scribe or scribes as well as Shakespeare.

Even nobler reasons for bringing notes to the press mitigated against their accuracy. Yelverton published Philips's sermons, to ‘quicken’ the voice of the preacher that would otherwise ‘perish in the ayre or in the eare’; ‘A.B.’ likewise printed Stoughton's sermons because the ‘precious labours of godly men…are not fit to vanish into the air, or to be buried in obscurity’.114 But these instances draw attention to the oral nature of the text; what is being trapped is not a text for the page but a performance rendered into words. Printing Hamlet Q1, when no one knew any other Hamlets would ever be made public, rescued the play for posterity, but what was being preserved may have been captured utterance; the gaps, segues and startling moments of vivid action that differentiate it from an authorial ‘literary’ text might in fact be a proud display of its performance heritage.

Many of the reasons for publishing a text from notes, then, were also reasons for inaccuracy. Only if the scribe's noting ability were at issue was a text likely to have accuracy as a goal. Egerton's Lecture was brought to the press, said its preacher, ‘by one who…respected the commendation of his skill in Charracterie, more than the credit of my ministery’; and Tyrrell feared that the youth who wanted to print his sermon ‘did it but to shew his skill and cunning in the dexteritie of his owne handewriting’.115 For such writers, precision may have been important. Indeed, shorthand teachers even seem to have used ‘their’ texts as advertisements: Burrough's 1654 sermons contain a printed puff for the noter: ‘these Sermons have been very happily taken by the pen of a ready writer, Mr. Farthing, now a Teacher of Shortwriting’.116 Hamlet Q1, is, however, too varied in quality to be by a single ‘good’ noter. It could, however, reflect the varying skills of, for example, a teacher flanked by his students learning the noting trade; Phillips some years later, denigrates ‘Pamphlets…rak'd from the simple collections of Short hand prentices’.117

If notes, then, were likely to be inaccurate, and often came without authorial sanction, what made them interesting to publishers? One answer is to do with ‘ownership’. As the publisher, not the author, would ‘own’ the text he had had printed, his authority residing in his entrance of the text into the Stationers’ Register, acquiring and printing a ‘bad’ copy gave him publishing rights to any subsequent ‘good’ copy. Preacher Henry Smith grudgingly agreed to ‘correct’ The Wedding Garment and publish it with William Wright, who had issued the text twice already from notes, ‘To controll those false coppies of this Sermon, whiche were printed without my knowledge…and to stoppe the Printing of it againe without my corrections, as it was intented, because they had gotte it licensed before’.118 As this makes clear, Smith was obliged to keep Wright as his publisher, because Wright already had the license for Smith's sermon. ‘Bad’ sermons could flush out good ones. E. Edgar published both Perkins’ Satans Sophistrie Answered (1604) and ‘The second edition much enlarged by a more perfect copie’, now named The Combat betweene Christ and the Divell Displayed (1606). Andrew Wise, meanwhile, who was fined for publishing Playfere's A Most Excellent and Heavenly Sermon upon the 23 Chapter of the Gospell by Saint Luke (1595) without authority (he had not entered it into the Stationers’ Register), still became its publisher when that same sermon was set out ‘a new’ by its preacher and renamed The Meane in Mourning (1596). Wise also then published Playfere's The Pathway to Perfection, allowing him to add in that text that ‘if any one who hath cast away his money upon the former editions [of Meane in Mourning], wil bestow a groate upon the true copie now set out by my selfe, hee may have this sermon with it for nothing’ – the result being that Wise was able to sell one ‘bad’ sermon twice while acquiring two separate good texts from Playfere.119 In all these instances, the first ‘bad’ text is from notes; the second is authorial. Though the familiar argument is that publishers did not care about the ‘goodness’ of a text, the fact that they spent money to reprint the texts once they had acquired them in ‘good’ form suggests something different. Expedience or desire may have led publishers to take on a text in noted form in order to force the ‘real’ version from the author. Most telling in this respect is the fact that publisher Nicholas Ling was able to acquire ‘good’ sermons and plays through printing ‘bad’ ones. He produced two editions of Henry Smith's The Affinitie of the Faithfull (1591) before publishing [The] Affinitie of the Faithfull…the Second Time Imprinted, Corrected, and Augmented. As Nicholas Ling was also publisher both of Hamlet Q1, and the text that responded to it a year later, Hamlet Q2 – perhaps, as Melnikoff suggests, financing both as part of his expansion into the world of play publishing120 – he may have paid for a noted Hamlet Q1 in the hope of acquiring Hamlet Q2 as a result. If that is so, Hamlet Q1, for Ling, is a form of blackmail – and, again, accuracy is not in question here. Indeed, the more inaccurate the text, the more the company is likely to release a corrective.

Conclusion

If Hamlet Q1 is a noted, audience, text, rather than a text taken by an actor-pirate, how should that affect our understanding of the play? In some ways, what has hitherto been concluded about the play remains unchanged: it is still a ‘performance text’, though it is no longer a direct one, as it has no relationship to players in the production itself. Nevertheless, it remains as a misty record of staged performance, offering, through its stage directions, additional information about the production. Textual oddities visible through or behind the noting process still remain interesting witnesses to a different moment in the life of Hamlet. For instance, when Q1 renders what in Q2/F is ‘& must th'inheritor himselfe have no more’ as ‘and must / The honor lie there?’ it is obvious that ‘honor’, which makes no sense, misrepresents the word said on stage, presumably ‘owner’. If, however, the noter mishears a word, that also gives us a performance variant, ‘owner’ being what the player said, and perhaps, though not necessarily, what Shakespeare once intended. Hamlet Q1, here, may preserve the aural experience – the sound and, in mishearing, even the pronunciation – of performance. Other instances, too, seem to record specific performance variants. Polonius is in Q1 called Corambis, and Reynaldo is called Montano. As Hibbard points out, Robert Pullen (‘Polenius’ in Latin) was Oxford University's founder, and John Reynolds was the President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford: Hamlet Q1, the only professional play of the period to boast Oxford performance on its title‐page, may record the play, or aspects of the play, in a localized version.121

Where differences emerge, if this is a noted play, is in the fact that the text need not be the record of a single performance. One noter may have attended the production on more than one occasion, or several noters might have taken texts on different days of performance, combining them later. The title page of Hamlet Q1, which promises the play ‘as it hath been diverse times acted’ in London, Oxford and Cambridge, already makes an ‘incongruous offer of a solitary record of multiple events’, and may, then, even broadcast that it is an interposition of several overlaid performances.122 If that is the case, the playbook represents simultaneously an effort to reconstruct Hamlets in performance and – in its choice of what to capture, what to drop, what to render accurately, and what inaccurately – an interpretation of them.

Finally, if Hamlet Q1 is a ‘noted’ text, then other plays may be too. Noting is not, of course, the only way a text might illegitimately reach the press; copies transcribed by actors or by the playwright's friends clearly sometimes circulated and were published. But the plays that do not seem to be direct transcriptions, and that were once called ‘bad quartos’, should perhaps be re-examined. We, these days, have eschewed the word ‘bad’, and have limited to ‘suspect’ those texts containing obvious features of memory, such as external echoes and internal repetitions – because of a belief that memorial reconstruction was the way they came about. But some of the play quartos that lack significant memorial features, and so have been repatriated as ‘good’, should perhaps be redefined as ‘bad’ again – or, rather, not ‘bad’ but ‘noted’, created, like their sermon counterparts, from ‘broken notes, penned from the mouth…mingled perhaps with the weake conceits of some illiterate Stenographer’.123

Whatever is the case, this article has argued that Hamlet Q1 is less likely to have been taken by an actor-pirate than an audience. That is true of ‘pirated’ products today, of course. Rogue audiences film blockbusters and put the results on the internet; film stars do not. ‘Pirating’, these days, is an audience phenomenon. Perhaps it always has been.

Heartfelt thanks to David Scott Kastan, Holger Klein, Zachary Lesser, Ivan Lupic, Will Poole, Paul Menzer, Holger Schott Syme, Arlynda Boyer, Rhodri Lewis, John Staines and William St Clair for their invaluable feedback on this article.