2.1 Introduction

For many years, policy discussions have focused on strategies to bring down greenhouse gas emissions using taxes, permits and other regulatory or statutory limits. Yet fossil fuel markets across the world remain littered with government programmes subsidising these emissions. The subsidies are large and act as a negative tax on carbon, slowing the transition to cleaner fuels, weakening the impact of carbon constraints and absorbing a significant portion of government revenues in many countries.

These factors have increasingly led governments and international organisations to view fossil fuel subsidy reform as an important carbon mitigation strategy and fiscal lever. The G20 reached an initial agreement in 2009 to ‘phase out and rationalise over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies’ (G20 2009), with members of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) group following suit (APEC 2009). In September 2016, China and the United States – the two largest greenhouse gas emitters – took that process another step forward by publicly releasing a voluntary peer-reviewed version of their fossil fuel subsidy reports (China 2015; G20 Peer Review Team 2016a, 2016b; United States 2015).

While the importance of subsidy reform is clear, widely varying estimates of subsidy magnitude and continuing battles over subsidy definitions slow reform efforts and complicate political consensus building. Differing coverage also affects reported figures: some assessments focus on subsidies to the consumption side of the market, others on producer subsidies and some on both. Global estimates vary by at least an order of magnitude, with a similar dispersion of country-specific estimates.

Beginning with a brief overview of the most common approaches to measure global subsidies to fossil fuels, this chapter discusses subsidy definitions, current global estimates, key causes of estimate variance and measurement gaps. Areas of common agreement are also presented; these are frequently broader than the numerical variance alone would suggest and are critical for successful reforms. The chapter concludes with several high-leverage opportunities for improving subsidy transparency going forward.

2.2 Measuring Global Subsidies to Fossil Fuels

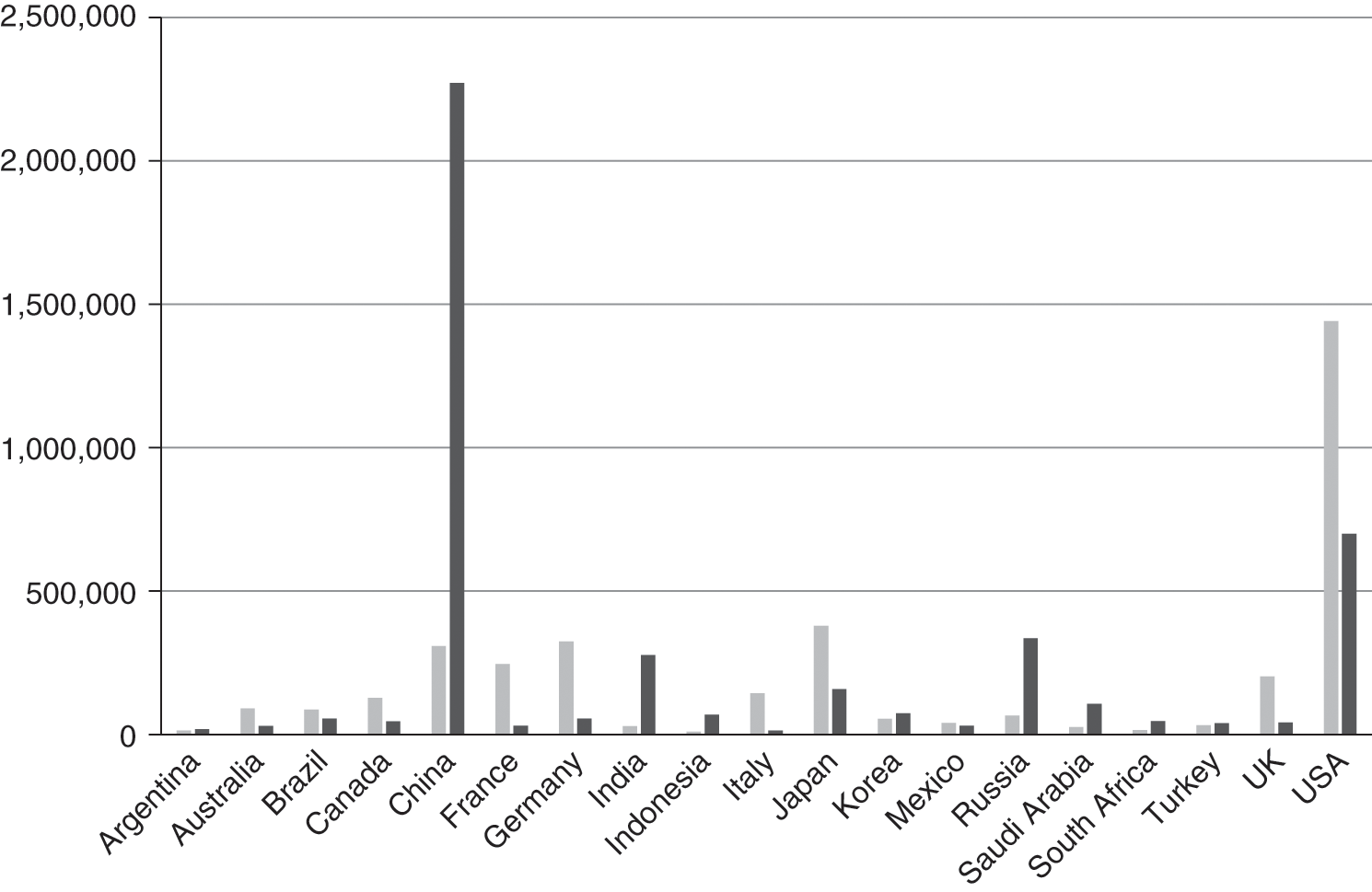

Global subsidy estimates have relied on two main strategies: quantifying the value transferred to market participants from particular government activities (programme-specific or inventory approach)Footnote 1 and assessing the variance between the observed and the ‘free market’ price for an energy commodity (price-gap approach). Each strategy has strengths and limitations (Table 2.1). To evaluate the impact of fossil fuel subsidies, data are generally aggregated into metrics of combined support that encompass many programme types, government institutions, levels of government and countries.

Table 2.1 Overview of subsidy measurement approaches

| Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Inventory |

|

|

| Quantifies value of specific government programmes to particular industries and then aggregates programmes into overall level of support. | ||

| Transfers include reductions in mandatory payments (e.g. tax breaks) and shifting of operating risks to the public sector, not just cash. Mandated purchase requirements are often captured, at least qualitatively. | ||

| Price gap |

|

|

| Evaluates positive or negative ‘gaps’ between the domestic price of energy and the delivered price of comparable products from abroad. | ||

| Total support estimate |

|

|

| Systematic method to aggregate transfers plus market support to particular industries. |

Inventories track individual subsidies, which helps to identify key political and economic leverage points for reform. However, the inventory approach does not delineate energy price impacts without significant additional analysis. Policy coverage across inventories may also differ due to definitional disagreements or data access problems.

Price-gap estimates do capture price effects. This approach has been used most prominently in recent years by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Because the approach requires less data than the inventories, it is useful for evaluating many countries at the same time, particularly when governments lack the capability or will to provide data on their market interventions. Price-gap results highlight countries with large pricing distortions; to develop a subsidy reform strategy, however, policy-specific information would be needed (Koplow 2015). Further, price-gap results provide only a partial picture. The many subsidies that boost industry profitability or allow marginal competitors to stay afloat – but do not affect equilibrium prices – are not captured. In addition, where energy resources are thinly traded, assessing an appropriate market reference price can be difficult. This is a particular challenge for network energy such as electric power, as well as fossil fuel–fired steam heat or natural gas delivery systems. Price-gap estimates should therefore be viewed as a lower bound of subsidy estimates (Koplow 2009).

Subsidy inventories compile programme-specific data on individual government supports to fossil fuels. The programme-level data can then be tallied to enhance transparency. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) total support estimate (TSE), for example, captures both pricing distortions (net market transfers) and transfers that do not affect end-market prices (net budgetary transfers) – effectively combining price-gap and inventory estimates. The TSE tracks individual policies on producer (via the producer subsidy equivalent (PSE)) and consumer (via the consumer subsidy equivalent (CSE)) sides of the market, allowing interactions to be evaluated. Government programmes that support the general structure of a particular fuel market – but not a specific producer or consumer – are tracked separately. The OECD’s approach is data intensive: their 2015 review of government support to fossil fuels included more than 800 subsidies provided by a diverse array of government agencies in OECD countries as well as in Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, India, China and South Africa (OECD 2015a).

Another approach to translate a subsidy inventory into a picture of market impacts is to simulate investment returns at the energy-asset level with and without individual subsidies. This technique highlights the degree to which the subsidies shift unprofitable projects into investable ones (Lunden and Fjærtoft Reference Lunden and Fjaertoft2014; Erickson et al. Reference Erickson, Downs, Lazarus and Koplow2017). Given the long capital life of most energy investments and the ability to continue production at lower prices once project capital has been ‘sunk’, this dynamic can lock society into multi-year carbon emissions. This approach can also quantify the level of subsidy ‘leakage’, where taxpayer money simply boosts the profits of projects that would have been profitable even without government support. These assessments provide highly granular information on subsidy transfer efficiency and environmental impacts, although they require detailed data on production sites and production economics that are not available for all fuels or all parts of the fuel cycle.

2.3 Defining and Identifying Energy Subsidies

As a starting point, most international organisations have adopted a subsidy definition developed by the World Trade Organization (WTO) under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (see Chapter 7). The WTO definition captures much of the needed complexity in the range of policies to be tracked, including credit support, tax breaks and equity infusions (see also Steenblik Reference Steenblik2007; Jones and Steenblik Reference Jones and Steenblik2010).

In practice, however, there are important differences in coverage across institutions, and the exclusion of particular types of policies from quantitative estimates is fairly common. Sometimes (as with externalities; see Section 2.4.2), this is due to methodological disagreements or differing objectives of the analysis. Often, however, resource or data limitations preclude systematic evaluation of more complex types of interventions.

Exclusion of entire groups of policies from inventories (credit and insurance support are frequently left out) reduces the reported national and global subsidy estimates. Even price-gap estimates are likely affected, despite relying on price differentials rather than policy details. For thinly traded commodities, price-gap reference prices rely on estimates of the domestic cost structure, and missing information on subsidies can generate an artificially low reference price.

While definitional disagreements cannot be resolved in this chapter, understanding key mechanisms of support is useful. A common view of subsidies prevalent in the general press focuses on cash payments from the government to an individual or corporation. In reality, a wide array of mechanisms is deployed to transfer value to, and risks from, particular forms of energy, many of which do not involve cash. While some subsidies increase the return to a specific party directly, many work indirectly by changing the risk and reward profile of a particular activity or investment. The WTO definition distinguishes these by referring to the latter set as ‘support’ rather than ‘subsidies’. However, either approach boosts expected returns for some individuals, companies or products while worsening the market position of competitors.

Indeed, a core function of markets is to allocate risks and rewards among investors, producers and consumers. Many fossil fuel subsidies function by shifting risks away from energy producers or consumers. Common mechanisms include tax breaks, subsidised credit or insurance, trade restrictions, price controls and purchase mandates. Although investment, safety, price, geological and regulatory risks are not consistent across fuels, they are significant factors in energy markets overall. Thus, the same type of subsidy may affect particular fuel cycles in quite different ways. For example, remote oil fields or nuclear reactors are extremely expensive with long and uncertain build times. They are highly sensitive to the cost of capital as a result. Nuclear firms thus benefit greatly from subsidies in the form of loan guarantees and caps on accident risks; liquefied natural gas facilities would have a similar profile. Fuel costs will be more significant for coal-fired plants than for reactors or for renewable resources such as wind or solar that have no fuel costs.

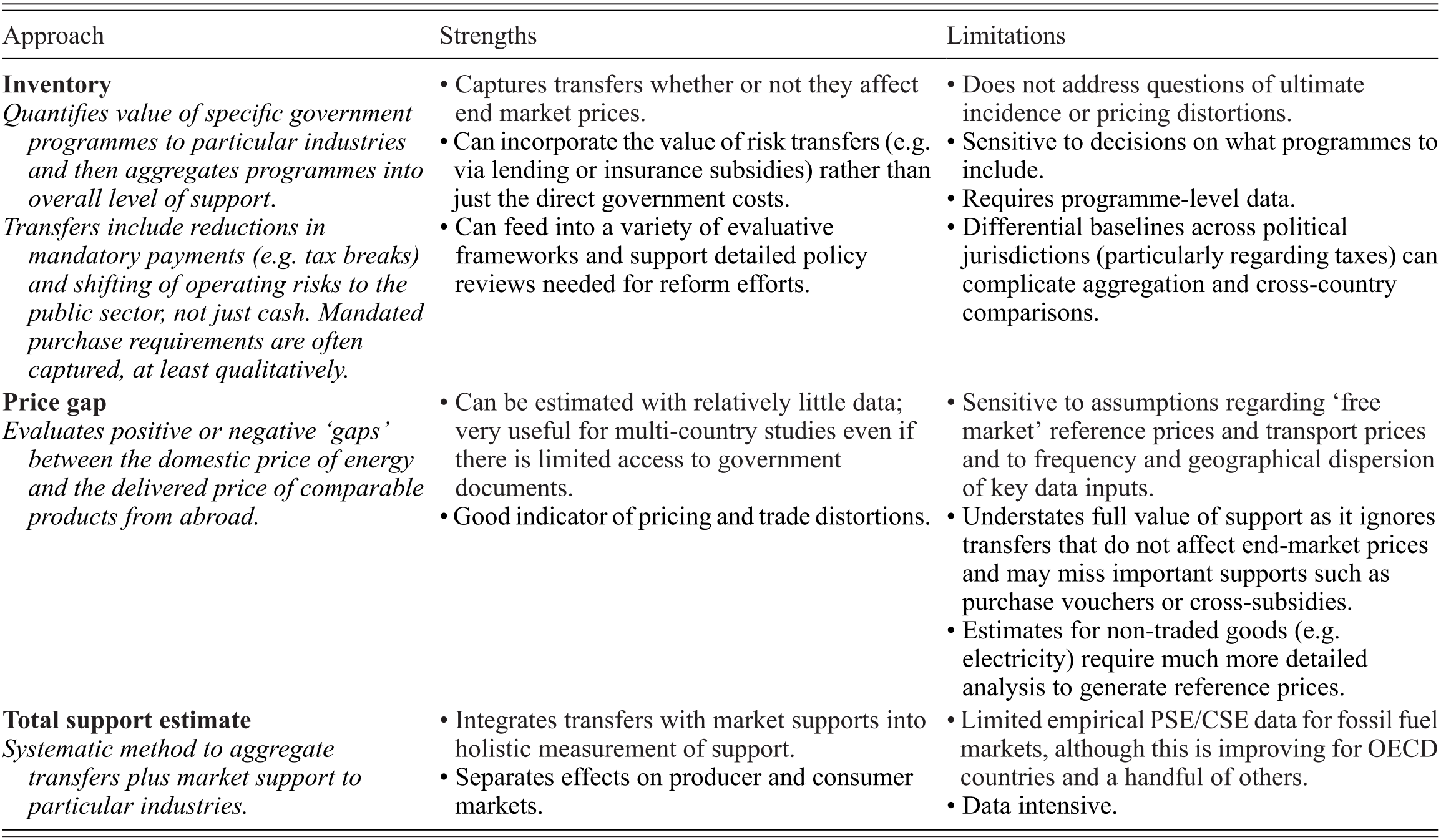

While not all subsidy types are relevant to every situation, focusing only on cash grants greatly understates the complexity and magnitude of subsidy-related market distortions. Table 2.2 provides a comprehensive overview of the main types of transfer mechanisms and how well they are captured within current price-gap and inventory estimates of fossil fuel subsidies. The many categories underscore both the complexity of markets and the importance of tracking all transfer mechanisms to ensure an accurate picture of subsidy-related market distortions for each fuel cycle.

| Intervention category | Description | Captured in current global estimates? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inventory | Price gap | ||

| Direct transfer of funds | |||

| Direct spending | Direct budgetary outlays for an energy-related purpose | Yes | Possiblyb |

| Research and development | Partial or full government funding for energy-related research and development | Yes | Possiblyb |

| Tax revenue forgonea | Special tax levies or exemptions for energy-related activities, including production or consumption; includes acceleration of tax deductions relative to standard treatment | As reported | Possiblyb |

| Other government revenue forgone | |||

| Accessa | Policies governing the terms of access to domestic onshore and offshore resources (e.g. leasing auctions, royalties, production-sharing agreements) | No | Possiblyb |

| Information | Provision of market-related information that would otherwise have to be purchased by private market participants | Yes | No |

| Transfer of risk to government | |||

| Lending and credit | Below-market provision of loans or loan guarantees for energy-related activities | No | No |

| Government ownershipa | Government ownership of all or a significant part of an energy enterprise or a supporting service organisation; often includes high-risk or expensive portions of fuel cycle (oil security or stockpiling, ice breakers for Arctic fields) | No | Possiblyb |

| Risk | Government-provided insurance or indemnification at below-market prices | No | No |

| Induced transfers | |||

| Cross-subsidya | Policies that reduce costs to particular types of customers or regions by increasing charges to other customers or regions | Partial | Possiblyb |

| Import or export restrictionsa | Restrictions on the free-market flow of energy products and services between countries | Partial | Yes |

| Price controlsa | Direct regulation of wholesale or retail energy prices | Some | Yes |

| Purchase requirementsa | Required purchase of particular energy commodities, such as domestic coal, regardless of whether other choices are more economically attractive | No | Yes |

| Regulationa | Government regulatory efforts that substantially alter the rights and responsibilities of various parties in energy markets or that exempt certain parties from those changes; distortions can arise from weak regulations, weak enforcement of strong regulations or over-regulation (i.e. the costs of compliance greatly exceed the social benefits) | No | No |

| Costs of externalities | Costs of negative externalities associated with energy production or consumption that are not accounted for in prices; examples include greenhouse gas emissions and pollutant and heat discharges to water systems | No | Generally not |

a Can act either as a subsidy or as a tax depending on programme specifics and one’s position in the marketplace.

b Intervention may be partially captured in price-gap calculations if it affects domestic prices to end users or if (as with cross-subsidies) the transfers move across fuel types that are measured independently in the price-gap analysis.

Many policies can act either as a tax or as a subsidy depending on the programme details and the associated market environment. If programme rules or disbursements change over time, the direction of impact can shift as well. Fees levied on oil and gas, for example, are often earmarked to support industry-related site inspections and cleanup or to fund infrastructure construction and maintenance. If the fees exceed these costs, they may partially act as a tax; if they cover only part of the cost, a residual subsidy will remain. Subsidies to energy consumers can sometimes act as a tax on producers, and vice versa. Teasing out these interactions is a significant challenge of subsidy measurement, although the OECD’s TSE approach has been effective in doing so.

For any specific company or energy asset, multiple subsidies are often at play, as beneficiaries try to maximise their subsidy flows across programme types and levels of government. This ‘subsidy stacking’ is sometimes limited by programme or tax rules but often is not. Subsidy stacking is common in both the private sector and with state-owned enterprises (SOEs), although in somewhat different forms. Private firms actively identify ways to tap into multiple lines of support. For SOEs, multiple levels of subsidies are often a side effect of their tax-exempt, taxpayer-supported operating environment.

Because SOEs are common in the energy sector (many countries even have a single, state-owned national champion dominating their oil and gas sector), including them in any subsidy review is critical. Indeed, SOEs play a larger role in the energy sector than in other parts of the economy. Of industrial sectors with the largest state-owned share worldwide, five of the six relate to fossil fuels: electricity, gas and steam for heat (27 per cent); oil and gas extraction (34 per cent); coal and lignite extraction (35 per cent); land transport and pipelines (40 per cent) and mining support activities (43 per cent) (Kowalski et al. Reference Kowalski, Büge, Sztajerowska and Egeland2013).

Annual budget allocations or bailouts to state firms are easy to spot. More complicated are subsidies to SOEs that become evident only when compared with a free-market baseline. SOEs may borrow money and pay interest, for example, but not at a market rate. They break even on operations, but this is far less than needed to generate a reasonable rate of return on billions in invested taxpayer capital. This lack of a required rate of return on public energy infrastructure can pose a large competitive impediment to innovative private energy providers who may be able to provide similar energy services in a cleaner or less-capital-intensive way (OECD 2016). SOEs sometimes pay no taxes, have inadequate insurance coverage or receive below-market access to publicly owned minerals. But these same institutions may also be mandated to provide low-cost energy to selected consumers or even housing for workers. Estimating the net effects of the subsidies against the cost-increasing social mandates on SOEs can be complex.

2.4 Current Estimates of Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies

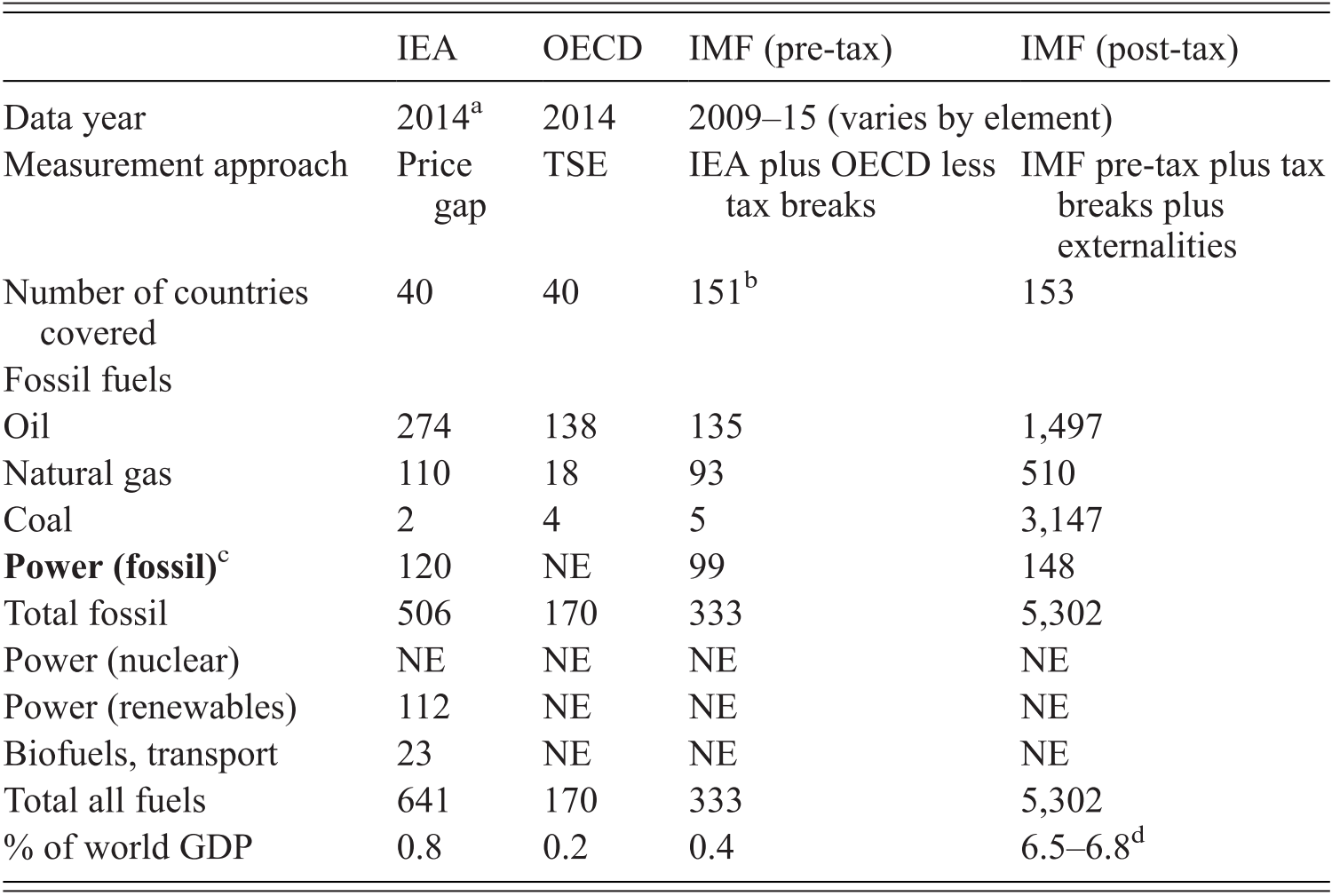

This section reviews the current estimates of global subsidies to fossil fuels, the main causes of variance and some of the important data gaps and definitional issues behind these differing results. The most comprehensive estimates for global fossil fuel subsidies are published by the IEA, the OECD and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IEA evaluates government subsidies to fossil fuel consumers on an annual basis using the price-gap approach. The OECD uses its TSE approach to produce a biennial inventory of government support to fossil fuel producers, to consumers and to the general infrastructure that benefits the industry. The IMF approach blends estimates from both the IEA and OECD, supplements them with internal estimates for additional countries and generates a ‘pre-tax’ estimate of subsidy value. The IMF also prepares a ‘post-tax’ estimate, which includes an imputed national sales tax on fossil fuels for countries where the IMF felt that current levels were too low and negative externalities associated with fossil fuels and transport. Some of these adjustments remain controversial with other practitioners (see below).

Other organisations have conducted fossil fuel subsidy assessments over the years, although less systematically. The World Bank prepared global estimates during the early 1990s using an approach similar to that used by the IEA (Larsen and Shah Reference Larsen and Shah1992; Larsen Reference Larsen1994), although in recent years the Bank has focused primarily on country-specific assessments of energy market structure and functioning (Kojima Reference Kojima2016). Similarly, country-specific reviews are periodically completed by national governments or non-governmental organisations and often supplement the international assessments.

Table 2.3 compiles the most commonly referenced global energy subsidy estimates. Even the lowest figure amounts to many billions of dollars per year and a material share of global gross domestic product (GDP) – despite significant remaining coverage gaps in terms of countries, subsidy types, and levels of government (see Box 2.1). The upper-bound estimate is equal to more than 6 per cent of global GDP, a remarkable figure given that all global manufacturing comprised only 16 per cent of global GDP in 2012 (McKinsey 2012: 6).

Table 2.3 Global energy subsidy estimates

| IEA | OECD | IMF (pre-tax) | IMF (post-tax) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data year | 2014a | 2014 | 2009–15 (varies by element) | |

| Measurement approach | Price gap | TSE | IEA plus OECD less tax breaks | IMF pre-tax plus tax breaks plus externalities |

| Number of countries covered | 40 | 40 | 151b | 153 |

| Fossil fuels | ||||

| Oil | 274 | 138 | 135 | 1,497 |

| Natural gas | 110 | 18 | 93 | 510 |

| Coal | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3,147 |

| Power (fossil)c | 120 | NE | 99 | 148 |

| Total fossil | 506 | 170 | 333 | 5,302 |

| Power (nuclear) | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| Power (renewables) | 112 | NE | NE | NE |

| Biofuels, transport | 23 | NE | NE | NE |

| Total all fuels | 641 | 170 | 333 | 5,302 |

| % of world GDP | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 6.5–6.8d |

Note: All amounts in 2015 USD; NE = not estimated.

a Base year 2014 selected to allow comparison across all sources. IEA (2015) shows lower fossil fuel subsidy estimates due to drops in the global price of energy.

b Of these, 123 countries had non-zero values.

c IEA data on source fuels indicate about half of the subsidy-weighted power capacity is natural gas fired and one-quarter coal fired. IMF’s estimates for fossil-fuelled electricity seem to include some non-fossil generation (Kojima and Koplow Reference Kojima and Koplow2015).

d Low-end estimate using IMF global GDP data; high-end using World Bank GDP data.

Box 2.1 Common gaps in energy subsidy estimates

Geographical.

Subsidies to producers in developing countries are systematically missing, although coverage of consumer subsidies in these regions is improving. The OECD includes some sub-national subsidies; worldwide, however, the overall capture rate of these policies remains low (IEA 2012; Koplow and Lin Reference Koplow and Lin2012; OECD 2011, 2015a).

Policy Type.

There is growing coverage of grants and many types of tax breaks (OECD 2015a). Substantial coverage gaps remain for producer support via subsidised credit or insurance, regulatory oversight and site remediation, energy security (shipping lanes, stockpiling) and bulk transport costs and tax-exempt corporate forms. Capture of subsidies through government-owned energy infrastructure or service organisations also remains low.

Non-Payment.

Price-gap metrics capture under-pricing but may not capture power theft and non-payment. These ‘hidden’ costs of power were larger than under-pricing in some regions (IEA et al. 2010: 17; Kojima and Koplow Reference Kojima and Koplow2015).

User Fees.

Many countries levy a variety of fees or taxes on fuels that are earmarked (hypothecated) for specific uses closely linked to particular fuels – for example, building and maintaining transit infrastructure or cleaning up oil spills or abandoned sites. These fees are sometimes improperly deducted from subsidy estimates, or shortfalls in actuarially based fee collections are not incorporated into subsidy tallies (Koplow Reference Koplow2009, Reference 45Koplow2010).

At this scale, the fiscal demands of subsidising fossil fuels can sometimes crowd out other social objectives. Federal revenues provide a useful proxy for a country’s ‘sustainable budget constraint’, or the amount it can spend without taking on debt to support current operations. Twenty-two countries (60 per cent) in the IEA sample spent more than 10 per cent of available revenues on their fuel subsidies. Indeed, nearly half of those countries spent more to subsidise fossil fuel consumption than they did on public health (Koplow Reference Koplow, Halff, Sovacool and Rozhon2014). Subsidy flows are disproportionately captured not by the poor but by the middle and upper classes (Arze del Granado et al. Reference Arze del Granado, Coady and Gillingham2010; Coady et al. Reference Coady, Gillingham and Ossowski2010).

Distortions across fuels are also relevant, particularly in light of concerns over climate change. Fossil fuels continue to capture the majority of support. In 2015, IEA data indicated that despite continued growth in government support to renewable energy and declines in oil prices (such drops tend to bring down consumer fuel subsidies by default), the fossil-fuel-to-renewable-subsidy ratio was still 2:1. This ratio was nearly 4:1 in 2014 and more than 10:1 as recently as 2008 (IEA 2016: 99).

Immediately evident from Table 2.3 is the extremely wide range of estimates, running from USD 170 billion (OECD) to USD 5.3 trillion per year (IMF). These differences are the result of three key factors: (1) the types of policies captured, (2) the valuation approach and (3) the geographical coverage. For example, while the IEA and OECD both cover roughly 40 countries, the OECD captures primarily advanced economies, while the IEA captures many more developing nations. The IMF, meanwhile, covers more than 150 countries for some fuels. The valuation methods also differ, with high estimates dominated by the inclusion of wide-ranging externalities and imputed taxes. The policies evaluated in both the OECD and the IMF pre-tax estimates also affect the results, and neither captures credit support, insurance subsidies, inadequate user fees, site reclamation or net support to SOEs in a systematic manner.

These factors sometimes work in opposite directions. The OECD captures a wider array of subsidy policies than the IEA, which increases its estimate. But the OECD does not include countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, which in 2014 accounted for USD 180 billion of the total USD 493 billion in fossil fuel subsidies measured by the IEA (IEA 2015).

Based on Table 2.3, coal subsidies appear extremely small. The one exception, the IMF’s post-tax value, is driven by large health-related externalities linked to coal (see also Figure 2.2). Low values for coal in the other estimates are more an indication of research gaps than a real absence of public support. Support commonly extended to coal producers includes subsidised transport infrastructure, below-market sales of coal lease rights, credit support to mines and coal-fired power plants and inadequate funding or insurance for regulatory oversight, pit reclamation and black lung disease among miners. Subsidies throughout Eastern Europe and China to district heating – often fuelled by coal – are also quite high but not well captured in the current data set. This is a useful illustration of why a systematic review of all types of supports is needed to generate accurate data.

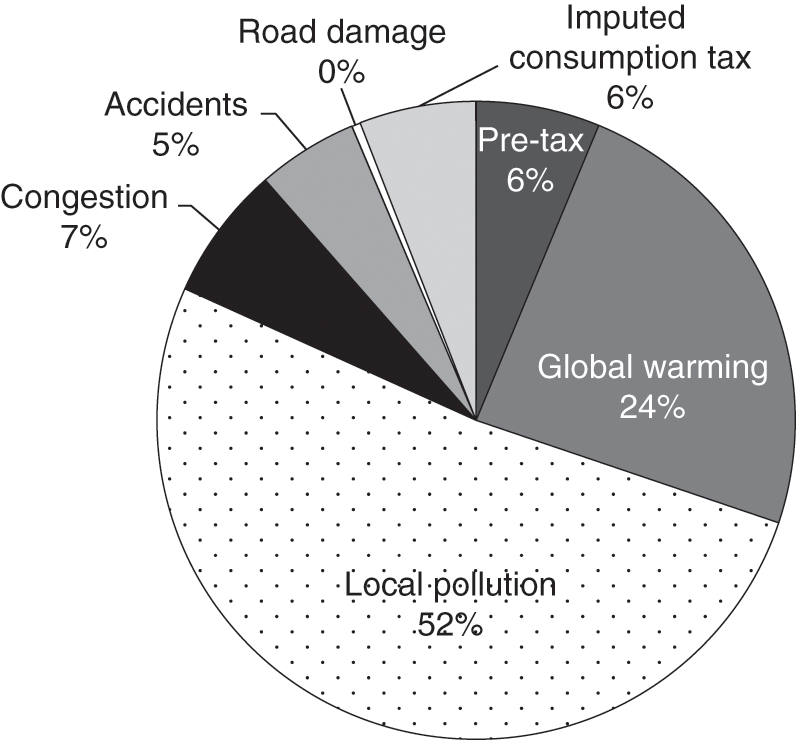

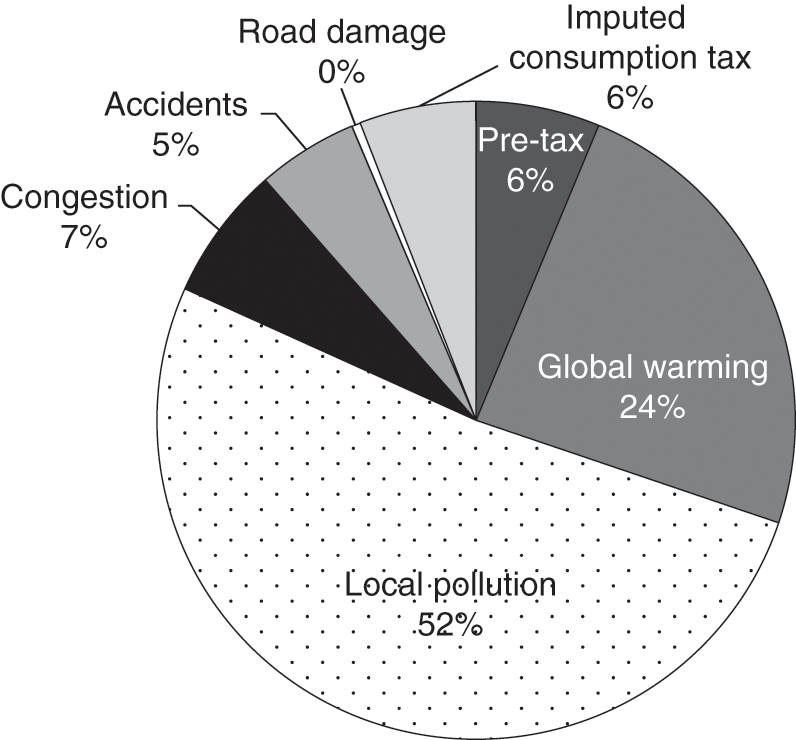

Figure 2.1 Composition of IMF post-tax estimates for oil

Figure 2.2 Composition of IMF post-tax estimates for coal

2.4.1 The Importance of Risk Subsidies in Energy Markets

Government policies that limit or eliminate key downside risks – such as unpredictable performance or market factors that drive project returns down sharply or even negative – can be extremely valuable in turning unprofitable projects into profitable, investable ones. Because quantification is challenging, this area remains one of the most significant gaps in existing global estimates.

Market participants are particularly concerned about preventing very bad outcomes, and markets often charge a premium for investments with higher downside risks (Ang et al. Reference Ang, Chen and Xing2006). The government providing a hedge against high downside risks is especially valuable for energy projects with untested technologies or long and uncertain delivery times. Examples include coal with carbon capture and storage and high-cost remote oil fields (which often have high upfront costs, missing key supporting assets such as ports, and very long breakeven periods). Indeed, large Russian onshore projects in the Arctic region took 30 years to begin production (Morgunova and Westphal Reference Morgunova and Westphal2016: 19).

Losses on securities investments are normally limited to the amount of funds invested. By contrast, many energy-related liabilities can well exceed the investment, such as through accidents or complex site reclamation. Long and uncertain build times for energy assets generate two major investment risks: high finance costs that compound for an extended period of time and increasing obsolescence risk if market conditions shift dramatically during the long gestation from investment to the start of operations. Government subsidies to these high-risk energy projects are common, even though lower-risk options often exist. In addition to credit or insurance programmes, direct state ownership or preferential provision of high-cost ancillary services (such as access roads, waste management or reclamation) are also used.

Government-provided hedges on these types of risks can boost the expected rate of return on the investment enough to clear the investors’ minimum rate of return. When this happens, long-lived, fossil fuel–intensive capital is deployed that otherwise would not have been, and emissions impacts may be felt for years or decades (OECD 2015a: 14; Erickson et al. Reference Erickson, Downs, Lazarus and Koplow2017).

Subsidies to operating and accident risks, such as below-market insurance premiums or liability caps, can have similarly perverse impacts. These programmes do not actually eliminate risks but simply transfer them from the subsidy beneficiary to somebody else – most often taxpayers. Plant neighbours or industries relying on a common resource (such as a waterway that is damaged by a spill) are at risk as well.

Subsidised public insurance programmes commonly socialise private risks. Nuclear accidents, earthquakes, flooding and dam failures are a few examples. In the fossil fuel sector, there are long-standing caps on oil spill liabilities. Subsidised insurance is also provided for land subsidence damages from coal mining and black lung disease among miners. Increasing attempts to transfer liability from leaks at carbon storage sites to the state (Lupion et al. Reference Lupion, Javedan and Herzog2015) would benefit coal and oil and be detrimental to low-carbon substitutes.

Risk subsidies are common with SOEs in the fossil fuel sector as well. Visibility is a problem: many SOEs implicitly provide liability coverage for all sorts of operating and accident risks simply by doing nothing in situations where capital providers would have forced private firms to purchase insurance cover. These exposures may not be formally evaluated or priced as they would be if a private firm operated in the same space. As a result, accurate prices on differential risks are missing when investment decisions across projects or economic sectors are made. By masking the economic costs of these higher-risk alternatives, insurance subsidies place energy options with lower economic or operational risks at a competitive disadvantage. Indeed, aggregate risks to society may actually rise. Decisions on where to drill for oil, where to locate a power plant or how heavily to fund worker safety training are affected by the observed financial costs of risk in insurance premiums. Many of these decisions relate to the deployment of long-lived capital and are largely irreversible once made.

2.4.2 Subsidy ‘Adders’: Imputed Taxes and Externalities

IMF’s post-tax estimate includes two major additions to the fiscal subsidy estimates: ‘missing’ taxes and several large externalities. These adjustments touch on two significant methodological debates within the subsidy area and dramatically increased the IMF’s estimates.

The concept of ‘missing’ taxes is a logical one: where the general sales tax or value-added tax on fossil fuels is lower than the prevailing rate on other goods and services in that state or country, there is a strong case that this discrepancy constitutes a tax subsidy (and is treated as such in OECD’s inventory). Cross-country adjustments are much more complicated, particularly when baseline tax systems differ. On these, the OECD defers to the country’s baseline system. By contrast, the IMF imputes a consumption tax even in countries that do not have such a tax on anything. The valuation impacts are large: IMF figures (Coady et al. Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and Shang2015) show USD 45 billion in imputed taxes for the United States, more than three times their estimate for all pre-tax fiscal supports.

Fossil fuel extraction, transport, processing and consumption can be messy, with all sorts of emissions to air, water and land. Many of the environmental and health costs from these emissions are not reflected in the market price of the fuels, dampening the incentive to shift to cleaner alternatives. In an effort to adjust for these factors, the IMF post-tax subsidy value also includes estimates for two main groups of externalities: transport and pollution from fossil fuel consumption. Production impacts – such as spills, flaring of associated gas or ecosystem damage – are not evaluated.

The IMF approach has raised some methodological issues. First, transport-related externalities are attributed to fuels primarily because most of the transport vehicles today burn petroleum. This can be seen in Figures 2.1 and 2.3; although 12 per cent of total estimates for fossil fuel are transport externalities, this jumps to 44 per cent for oil. However, the causal factors of the externalities are not generally fuel specific. Road damage is a function of vehicle trips, vehicle weight and the quality of the roadbed. Congestion and accidents occur regardless of the fuel being used, and at least part of the external cost of congestion is being internalised by drivers through lost time.

Figure 2.3 Composition of IMF post-tax estimates for all fossil fuels

The case for linking pollution externalities to fossil fuels is much stronger. The polluter-pays principle and economic efficiency both support the idea that external costs should be reflected in the prices of the activities that trigger them. This is not always easy to do. Much of the air pollution damage from fossil fuel–related activities is local or national rather than global. Accuracy requires many localised data inputs, something that the IMF (Coady et al. Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and Shang2015) has worked hard to build into their more recent estimates.

However, disagreement on which externalities to include, their massive scale and the variability across estimates have led some experts (Steenblik 2014) to argue that externalities should not be lumped in with fiscal subsidies but rather tracked as a separate category. This is a tracking issue, not one of importance: there is near-universal agreement that fossil fuel externalities are real and distorting energy markets. But keeping the values separate from fiscal subsidies has merit: externality figures are much larger than the pre-tax subsidies the IMF tabulated worldwide. Indeed, the IMF’s pre-tax subsidy values comprise less than 10 per cent of the total for oil, coal and all fossils and less than 20 per cent for natural gas. Yet, literature reviews of externality magnitudes by fuel cycle indicated large estimate variance (Kitson et al. Reference Kitson, Wooders and Moerenhout2011; Burtraw et al. Reference Burtraw, Krupnick and Sampson2012). Specifically, the high estimate for coal externalities was 155 times higher than the low estimate and for oil more than 400 times higher. Combining the fiscal subsidies and externality estimates risks marginalising the important policy reforms needed on the fiscal side. Further, the uncertainty across research efforts provides a political lever for industry to argue that nothing should be done without ‘further study’, delaying important structural transformation in the energy sector.

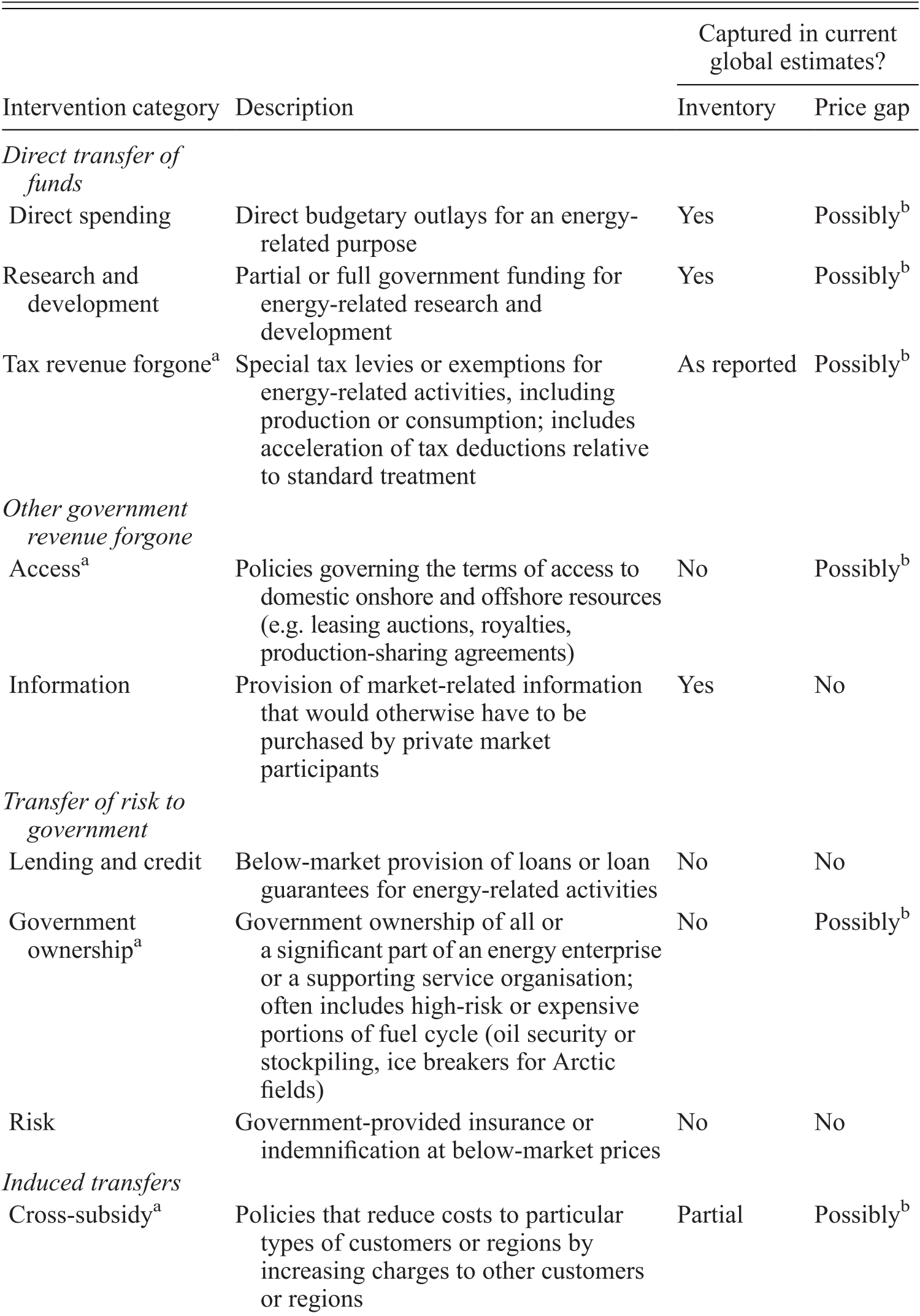

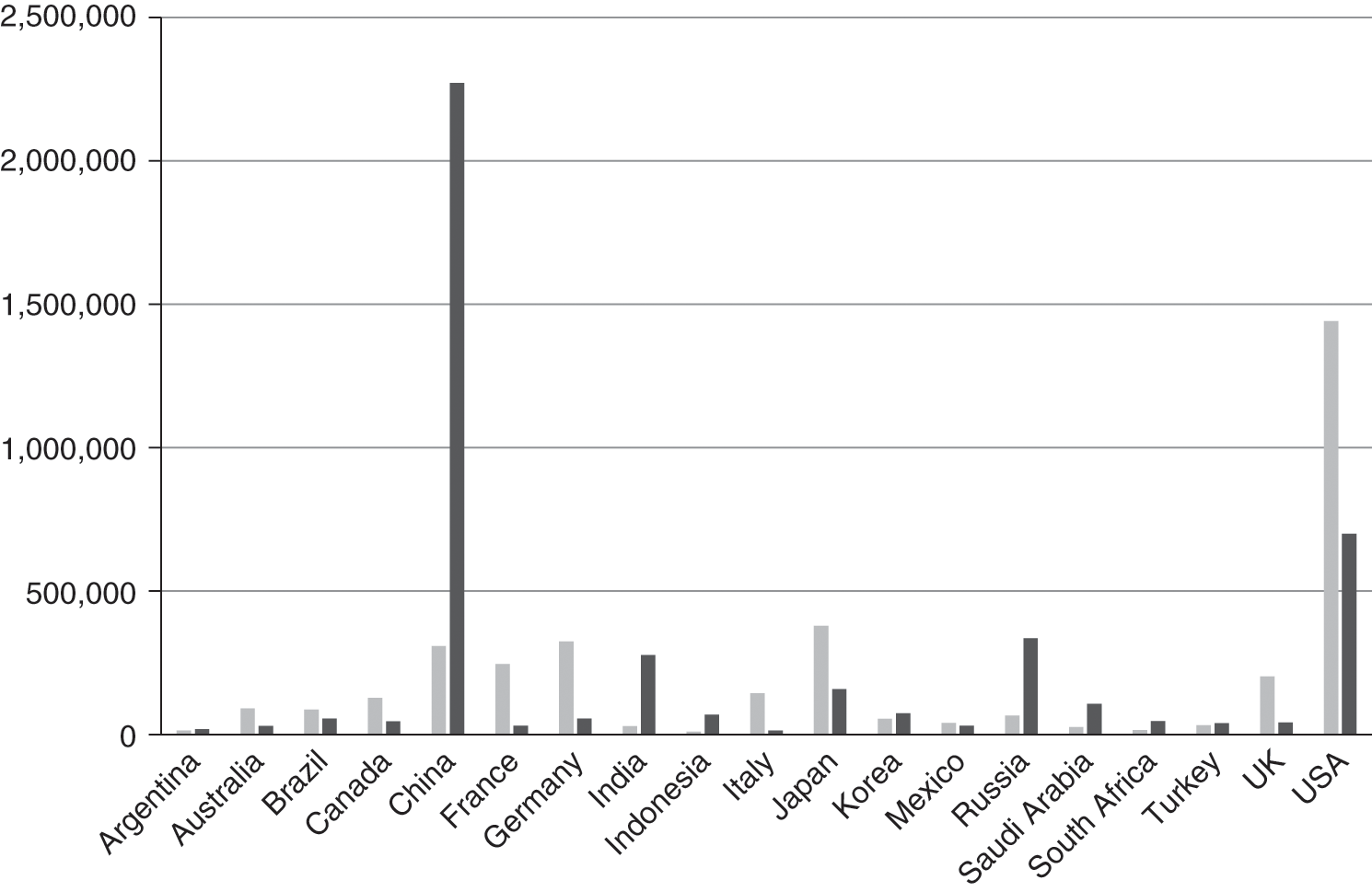

2.4.3 Intra-Country Variance: The Case of the United States

If subsidy evaluations use different sets of policy interventions in calculating subsidy value, numerical differences are inevitable. Looking at real data for a specific case helps to illustrate this issue more concretely. Figure 2.4 compares data on US fossil fuel subsidies from five different sources (from different parts of the US federal government, non-governmental organisations and industry) that catalogued intervention-level support. Figure 2.5 breaks estimates down by subsidy type.

Figure 2.4 Estimated US subsidies to fossil fuels (millions USD/year)

Note: Data years: 2013 (Energy Information Administration, Oil Change International), 2014 (OECD), average projected 2016–25 (US Treasury).

* Federal subsidy estimates only; no sub-national data in totals.

ǂ Includes data for oil and gas only.

Figure 2.5 Coverage disparity across subsidy types in the United States

* Insufficient data to calculate credit subsidies. Face value of commitments to fossil fuel projects in 2013 was about USD 4.5 billion/year (Oil Change International 2014).

The dispersion of US-specific estimates mirrors the global pattern in Table 2.3. Oil Change International, a non-governmental organisation, identified far more subsidies than did the other sources (USD 32.6 billion/year compared to USD 14.2 billion/year for the OECD and only USD 8.1 billion/year in the US government’s reporting to the G20). Although the US G20 self-review generated a much lower estimate than the OECD, it was still more than double the USD 3.5 billion estimated by the US Energy Information Administration for the fiscal year 2013 (US EIA 2015). This may partly be the result of different base years, although primarily it is a reminder that conflicts remain even within countries on how to identify and value subsidies. In the United States, this plays out in part by how the US Congress defines the allowable research scope the Energy Information Administration can use when it tabulates energy subsidies.

The zero value is put forth by Stephen Comstock, director of tax and accounting at the American Petroleum Institute. The institute is the largest trade association representing oil and gas interests in the United States. Comstock (Reference Comstock2014) noted that ‘[c]ontrary to what some in politics, the media and most recently, the president during the State of the Union, have said, the oil and natural gas industry currently receives not one taxpayer “subsidy”, “loophole” or “deduction”.’

Although this is a refutable statement and one that runs counter to many US federal agencies that have assessed US subsidies,Footnote 2 Comstock is pursuing a classical political strategy to simply deny that key interventions are subsidies at all. Often this involves claims that the subsidised treatment of one’s own industry is part of the baseline tax system rather than a deviation. By introducing doubt, this approach can deflect attention away from subsidy removal, slowing or blocking reform efforts.

Blank categories in Figure 2.5 indicate research or data limitations rather than a real absence of subsidies. This issue is a global one: a review of subsidy data sources in China, Germany, Indonesia and the United States (Koplow et al. Reference Koplow, Jung, Lontoh, Lin and Charles2010) indicated that data gaps for the more complex subsidy mechanisms were common. For example, the OECD’s inventory does not yet track credit or insurance subsidies in its biennial review.

Within the United States, coverage of SOEs was fairly limited, even though many utilities are publicly owned and also reliant on fossil fuels. These utilities benefit from a wide array of government support via tax exemptions and subsidised credit and insurance, though often at the municipal rather than the federal level. Mineral access – which concerns lease competitiveness and reduced royalties – is not captured by the OECD or the US Treasury and is only partly captured by Oil Change International. Energy-related user fees are common at both the state and federal levels in the United States, often funding health and safety oversight of extraction sites and cleanup of improperly closed wells or mines or other similar fuel-specific damages. Credit and risk subsidies arise through insurance caps, transfer of health or reclamation risks to governments and subsidised borrowing for government-owned energy infrastructure. None of these areas are properly captured in the existing data on US fossil fuel subsidies. Industry-specific regulatory exemptions are a final, though challenging data gap. These exemptions are both extremely complicated to quantify and fairly common in the United States for oil and gas (Kosnik Reference Kosnik2007). While it may be unrealistic to expect a full subsidy inventory, comparing reporting by category can highlight the most important gaps to fill.

2.5 Subsidy Measurement: Areas of Agreement and the Path Forward

Despite a wide range of subsidy valuations, there is an emerging global consensus supporting fossil fuel subsidy reform in multiple areas. Many countries see important benefits domestically from unilateral reform. Incremental benefits from multilateral reform require consistent data reporting worldwide; while those benefits may not always outweigh parochial domestic interests, they help to overcome them. Even without full agreement on how every type of subsidy should be measured, there is growing alignment both on the types of policies that give rise to subsidies and on a significant range of valuation issues.

Perfect agreement on subsidy definition and valuation is unlikely a panacea, as political interests can still benefit by generating divergent estimates. Because gains to subsidy recipients tend to be concentrated, while the groups paying for them are diffuse, recipients can more easily mobilise and fund efforts to create and protect subsidy programmes (Victor Reference Victor2009). Part of that strategy may include slowing or blocking subsidy reporting or frequently challenging the official estimates. The incremental cost and research needed to value complex subsidy mechanisms such as risk transfer can extend the advantage of the incumbents.

As subsidy reporting and reform grow, however, the range of policies widely viewed as subsidies continues to grow with them. Groups harmed by subsidies can better gauge the benefits of removing distortions and often find reform allies in the finance ministries of their governments. The following overview highlights areas of progress and some important residual areas of disagreement.

Direct Transfers and Price Controls.

There is broad agreement that direct transfers to particular industries, as well as policies that allow domestic fossil fuel purchases to occur below market prices, are important subsidies and fairly easy to measure. Remaining definitional disagreements seem to have a large political component. For example, subsidy supporters have defined some types of support as not being environmentally harmful when gauging compliance with G20 fossil fuel phase-out commitments. Another argument is that selling below world prices is not a subsidy as long as a country markets fuels above its production cost, as some countries of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries have done (Koplow 2012).

Tax Expenditures.

All international organisations working in this area recognise tax breaks as subsidies. Subsidy inventories have done a good job capturing key tax breaks at the national level, with some sub-national coverage as well. Recent requirements by the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB 2015) in the United States should make this reporting both more extensive and more standardised, even at the state and local levels. Similar requirements in other countries are needed, as are methods to integrate tax expenditure data across countries.

Preferential Credit.

There is a fairly broad consensus that preferential credit, often through subsidised loans or government guarantees, provides significant subsidies to beneficiaries. While patterns in gross loan commitments may indicate a bias in favour of particular fuel cycles and are more easily tracked, subsidy magnitude is driven by the concessional element of finance packages. Data on loan terms and project or borrower risk profiles are systematically lacking and likely a key impediment preventing inclusion of credit subsidies in subsidy inventories, despite a stated intent to do so since at least 2011 (OECD 2011: 25). Although sub-national credit support is common and in principle could follow the same reporting approach as for national supports, consolidation of fragmentary data sources remains difficult. Valuing credit subsidies remains a challenge. Administrative costs are sometimes ignored, and countries often calculate interest-rate subsidies against their treasury’s cost of providing the funds rather than adjusting for the much higher risk of the enterprise being supported. The Center for Finance and Policy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has been working on more accurate valuation methods for sovereign credit programmes (e.g. Lucas Reference Lucas2013). Even if valuation issues could not all be worked out in the short term, including concessional elements of credit programmes within subsidy inventories would be a big step forward.

Liability and Operating Risks.

Again, there is broad theoretical consensus that markets should price these types of risks, thereby encouraging selection of lower-risk energy goods and services. Although country studies may include a smattering of insurance programmes subsidising particular aspects of a fuel cycle, these reviews are not systematic and often qualitative rather than quantitative. Coverage is so weak that simply compiling a full list of programmes that subsidise or cap fuel cycle risks would be a step forward. As with concessional credit, the OECD fossil fuel subsidy inventory plans to include risk transfers in future assessments (OECD 2011: 25).

Externalities.

There is broad agreement that fossil fuel–related externalities are large and should be tracked and that corrective policies (such as Pigouvian taxes) may often be warranted. Areas of disagreement include the boundaries of analysis (such as whether to treat traffic congestion or vehicle accidents as fuel related) and narrowing the range of estimated values to support workable policy solutions.

State-Owned Enterprises.

Subsidies to SOEs cut across many policy types, but many are missing from the government tracking and reports that capture supports to private-sector players. OECD (2015b, 2016) has developed useful guidance to benchmark whether SOEs are operating on an equal basis with private competitors (domestic or international) or whether they are benefitting from direct or implicit subsidies from the state. Centralising, standardising and expanding data on fossil fuel subsidies to SOEs is a critical area of needed improvement. A useful starting point is existing data within the IEA, World Bank and IMF on the cost structure of core energy assets, which they have developed in the course of their work for member countries or to support price-gap reference prices for network energy.

2.6 Conclusion

Increasing international commitments to disclose and reform fossil fuel subsidies provide a backdrop against which subsidy reporting can continue to grow. International agreements are largely voluntary, but progress is rewarded with fiscal savings, economic efficiency in energy-intensive sectors and the alignment of fiscal policies with environmental goals. Near-term steps to accelerate the change should include mandating energy subsidy reporting to the OECD in the same way it is required for agriculture (Whitley and van der Burg Reference Whitley and van der Burg2015), broadening the peer review process of the G20 and APEC fossil fuel subsidy reports, expanding the OECD’s research mandate and funding to include credit subsidies and risk transfers and encouraging the US GASB to extend sub-national tax expenditure reporting into other types of subsidies and to international affiliates.

Increased coordination across international organisations is also needed to help streamline and accelerate subsidy transparency and reform. Despite the inevitable institutional challenges, a standing working group on subsidies including the IMF, World Bank, IEA and OECD should be established with a technical mission to identify and resolve key areas of reporting or measurement divergence. Useful initial areas on which to focus include price-gap calculations for network energy; the treatment of externalities in parallel with fiscal subsidies and ways to narrow the range of uncertainty on externality estimates; and accelerating and standardising the inclusion of credit and liability subsidies in existing inventories.

3.1 Introduction

Much of the world’s private sector receives support, interventions and subsidies from the public sector. In the case of energy subsidies (including those for fossil fuels), their use has been linked to energy security, domestic energy production and access to energy. In recent years, however, the heavy economic, social and environmental costs of subsidies for fossil fuels and the development of other means to achieve the same objectives have led to demands for their removal. High-level commitments to phase out fossil fuel subsidies have been made by the Group of 7 (G7), Group of 20 (G20), Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), North American Leaders’ Summit and EU countries, as well as in international agreements such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (APEC 2009; European Commission 2011; United Nations 2015; G20 2016; G7 2017).

To increase understanding of the rationale and potential for phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, this chapter first outlines evidence of their economic, social and environmental costs, as well as the benefits of and opportunities for reform. It then synthesises lessons from the literature and from case studies on several countries that have made progress in phasing out subsidies before setting out the key ingredients for successful reform.

3.2 Economic, Social and Environmental Consequences of Fossil Fuel Subsidies

There are often valid public policy objectives for fossil fuel subsidies, including improved energy security, domestic energy services and access to energy. Production subsidies, for example, may temporarily sustain jobs in the oil and gas sectors, and consumption subsidies may help to improve access to (affordable) energy. The short-term benefits of subsidy reform may not be distributed evenly and depend on the approach and complementary measures adopted (see Section 3.3).

Nonetheless, evidence demonstrates that the costs of subsidies far outweigh their benefits and that less costly alternatives can achieve the same policy objectives (UNEP 2015). The interconnected economic, social, public health and environmental costs of fossil fuel subsidies are discussed in the following sections.

3.2.1 Macroeconomic and Fiscal Consequences

Fossil fuel subsidies place a burden on government budgets (and on wider trade flows and exchange rates), a burden that increases when international fuel prices rise and governments must offset a portion of that rise. Consumption subsidies lead directly to greater domestic demand for energy products that must be imported or that could be exported, reducing revenue and worsening the trade balance (IEA et al. 2010).

Governments often use under-pricing of energy inputs to support production across sectors or firms (IEA 2014). The purpose is often to promote economic development by giving domestic energy-intensive industries or energy producers an advantage and to increase the competitiveness of export-oriented firms (IEA 2014). These subsidies may, however, result in inefficient allocation of resources across the economy by undermining efficiency and encouraging over-consumption.

Countries where energy prices are lower than the cost of its production are characterised by very high consumption per capita and low energy efficiency. Venezuela, for example, has some of the world’s highest fossil fuel subsidies, and its petrol consumption per capita is 40 per cent higher than in any other Latin American country and more than three times the regional average (UNEP 2015). The impact of such inefficient use of resources by key industries and energy production goes beyond Venezuela, as its highly subsidised oil is distributed internationally via the black market or government deals with selected allies (Hou et al. Reference Hou, Keane, Kennan and te Velde2015). Furthermore, every subsidised barrel sold domestically at a subsidised price cannot be exported at the international market price for hard currency.

Similarly, subsidies for fossil fuel production can promote consumption of one type of fuel by reducing input costs for energy service providers (see also Chapter 2). Such policies were often applied to the coal used to produce electricity in Eastern and Central Europe and still apply in many countries, including China and India (IEA et al. 2010). Subsidies to inputs for electricity production, for example, can create a vicious cycle by artificially lowering costs and discouraging investment in efficiency, maintenance and increased supply (IEA 2014). Such under-investment reduces the ability of companies to invest in meeting growing demand, especially by potential consumers who lack access to energy.

3.2.2 Social Consequences

Consumer subsidies are justified as a way to help poor households obtain access to energy. There is evidence, however, that fossil fuel subsidies are regressive, with their benefits accruing mainly to middle- and higher-income groups, while their costs are borne by the whole population (IEA 1999). A review by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) of subsidies in developing countries found that only 7 per cent of the benefits accruing from fossil fuel subsidies reached the poorest 20 per cent and that subsidies for gasoline (petrol) and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) are particularly regressive (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 The wealthy benefit most from fossil fuel subsidies in developing countries

Fossil fuel subsidies often exacerbate inequalities, particularly in countries where most people lack access to electricity or commercial fuels and rely on biomass collected in rural areas or purchased at an unsubsidised cost in urban areas. These people do not share the benefits of lower prices for commercial energy, as subsidies tend to go to large, capital-intensive projects or to wealthier users, sometimes at the expense of support to smaller-scale biomass-based energy (van der Burg and Whitley Reference van der Burg and Whitley2016).

Subsidies may also prevent the poorest people from accessing energy. Where electricity production is based on fossil fuels, subsidies can create a disincentive to invest in the power sector because without this support the sector is unable to recover the full costs of production. On average, electricity tariffs in sub-Saharan Africa cover only 70 per cent of the cost of power production (Alleyne et al. Reference Alleyne, Josz and Singh2014), and such under-investment in the power sector contributes to poor access, transmission and distribution losses and persistent shortages (Alleyne et al. Reference Alleyne, Josz and Singh2014).

Subsidies also make households less likely to invest in energy-efficient equipment and appliances; when a fuel is subsidised, there is little savings incentive to buying more energy-efficient devices. The higher the rate of fuel or electricity subsidy, the longer the payback period for household investment in energy efficiency and the lower the likelihood of households making such investments (IEA 2014).

Energy subsidies often start as temporary income buffers. According to many governments, they aim to protect populations from international price hikes (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Coady and Fabrizio2013). In fact, governments may be less concerned about fluctuating energy prices than about resulting fluctuations in income (potential consumption) and its distribution. Since fossil fuel subsidies can aggravate inequality and undermine the capacity of the poorest to access energy, they may do more harm than good in protecting populations from volatile energy prices.

A significant proportion of spending on fossil fuel subsidies could be redirected to national economic or social development goals, such as improving health services and education, and financing the development of low-carbon infrastructure (Koplow Reference Koplow, Halff, Sovacool and Rozhon2014; van der Burg and Whitley Reference van der Burg and Whitley2016). In several countries, the levels of fossil fuel subsidies may be equivalent to, or exceed, expenditure on health (Figure 3.2). Many aid-recipient countries also subsidise fossil fuels at levels that exceed the official development assistance they receive (Whitley and van der Burg Reference Whitley and van der Burg2015).

3.2.3 Public Health Consequences

In many countries, the pollution caused by combustion of fossil fuels is a major public health problem (IEA 1999). Estimates suggest that air pollution resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels and biomass caused 3.7 million premature deaths worldwide in 2012 (Parry Reference Parry2014). The health hazards are borne disproportionally by people who cannot avoid heavily congested and polluted urban areas (IEA 1999).

An analysis of countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that the cost of mortality due to air pollution was USD 1.6 trillion in 2010, with almost USD 1 trillion attributable to road transport (OECD 2014). Most of these costs stem from the combustion of fossil fuels (Gorham Reference Gorham2002), of which a large proportion is subsidised (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Hazlett and Mahdavi2017).

The IMF has found that phasing out fossil fuel subsidies would reduce emissions of sulphur dioxides, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter, which are not only public health hazards but also cause damage to infrastructure and environmental problems such as acid rain. A combination of subsidy reform and corrective taxes on fossil fuels could result in a 23 per cent reduction in these emissions and a 63 per cent decrease in deaths worldwide from outdoor fossil fuel air pollution (Parry et al. Reference Parry, Heine, Lis and Li2014).

3.2.4 Environmental Consequences

Fossil fuel subsidies have a climate impact. Nonetheless, governments are subsidising the production and consumption of carbon-intensive fossil fuels rather than increasing the cost of fuel and activities that produce greenhouse gas emissions. The International Energy Agency (IEA), based on their estimates of fossil fuel consumption subsidies in 40 countries, found that 13 per cent of global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions receive an incentive of USD 115 per tonne through subsidies and that only 11 per cent of energy-related emissions are subject to a carbon price (on average USD 7 per tonne) (IEA 2015). These subsidies undermine the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit the global average temperature increase to well below 2°C. Analysis shows that one-third of oil reserves, half of gas reserves and more than 80 per cent of current coal reserves should remain unused from 2010 to 2050 to meet the 2°C goal (McGlade and Ekins Reference McGlade and Ekins2015).

If governments removed current subsidies for exploration and production, the economics of many fossil fuel exploration and production projects could shift. The Stockholm Environment Institute found that at recent oil prices of USD 50 per barrel, subsidies are needed to make nearly half of yet-to-be-developed oil fields profitable in the United States (Erickson et al. Reference Erickson, Down, Lazarus and Koplow2017). Existing subsidies for coal and gas production may also lock in high-emission sources of electricity generation by increasing investment in those activities (IEA 2013; Erickson Reference Erickson2015).

Subsidising fossil fuels also has an impact on the global goal of transitioning to more diverse low-carbon energy systems. Subsidies can hinder investment in renewables and energy efficiency, perpetuating dependence on fossil fuels (Bridle and Kitson Reference Bridle and Kitson2014). Slow adoption of renewables also reduces the pace of their development and of cost reduction as technologies mature. Put simply, the more a government subsidises fossil fuels, the more it should subsidise renewables if it wants to achieve a level playing field.

The impact of fossil fuel subsidies on investment in renewables is striking in the Middle East, where more than 33 per cent of the region’s electricity is generated by oil (Bridle et al. Reference Bridle, Kitson and Wooders2014). Both oil and natural gas are heavily subsidised, with oil subsidies holding electricity generation costs at around 30 per cent of the level they would be if full reference prices were paid, while gas subsidies reduce costs to around 45 per cent of the unsubsidised level. As a result, low-carbon power technologies struggle to compete against existing or new capacity (IEA 2014). Fossil fuel subsidies for consumers also undermine the development and commercialisation of new technologies that might become more economically (and environmentally) attractive.

3.3 The Benefits of, and Potential for, Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

The consequences of fossil fuel subsidies could be reversed by reforming these subsidies. A review of studies on the economic impact of reforming subsidies for the consumption of fossil fuels suggests that phasing them out would increase global real income or gross domestic product (GDP) by up to 0.7 per cent per year to 2050 (Ellis Reference Ellis2010). This benefit would not be spread equally, however, as fossil fuel importers would see rising GDP while producers would lose income. Given uncertainties about the exact impact of subsidy removal, these are only rough estimates, but they illustrate what is at stake.

The reform of fossil fuel subsidies could also generate health and environmental benefits. Several international organisations analysed data on fossil fuel consumption subsidies in developing countries and estimated that phasing out the subsidies between 2011 and 2020 would lower emissions of air pollutants that are harmful to public health and the environment (IEA et al. 2010). Limited evidence also suggests that the economic, social and environmental benefits of fossil fuel subsidy reform would exceed the transitional costs of such reform (Burniaux et al. Reference Burniaux, Château and Sauvage2011).

The Global Subsidies Initiative has found that removing fossil fuel consumption subsidies in 20 countries between 2017 and 2020 could reduce average national emissions by approximately 11 per cent (Merrill et al. Reference Merill, Bassi, Bridle and Christensen2015; see Chapter 8). Data for the G20 countries suggest that parallel emissions savings from the removal of subsidies for fossil fuel production could be roughly equivalent to eliminating all emissions from the aviation sector (Gerasimchuk et al. Reference Gerasimchuk, Bassi and Dominguez Ordonez2017).

Despite clear evidence of the costs of fossil fuel subsidies and the potential virtuous cycles that could result from their removal, governments are often reluctant to reform for several reasons (Whitley Reference Whitley2013; see Chapter 1). Some are explicit (or more openly discussed), such as a lack of information, whereas others are implicit and include the influence of special interests. Governments sometimes subsidise fossil fuels because they lack other effective means and institutional capacity to adopt more suitable policies (Victor Reference Victor2009). Taken together, these barriers to reform create inertia around subsidies, even in the context of new technological, economic and social developments (OECD 2007).

Despite the challenges of reform, several countries have made progress in reforming subsidies for fossil fuels across a number of sectors. Egypt, for example, raised fuel prices by 78 per cent in 2014 and will double electricity prices over the next five years (see Chapter 15); Indonesia raised petrol and diesel prices by an average of 33 per cent in 2013 and by another 34 per cent in 2014 (see Chapter 11) and India eliminated liquefied petroleum gas subsidies in 2014 (see Chapter 12).

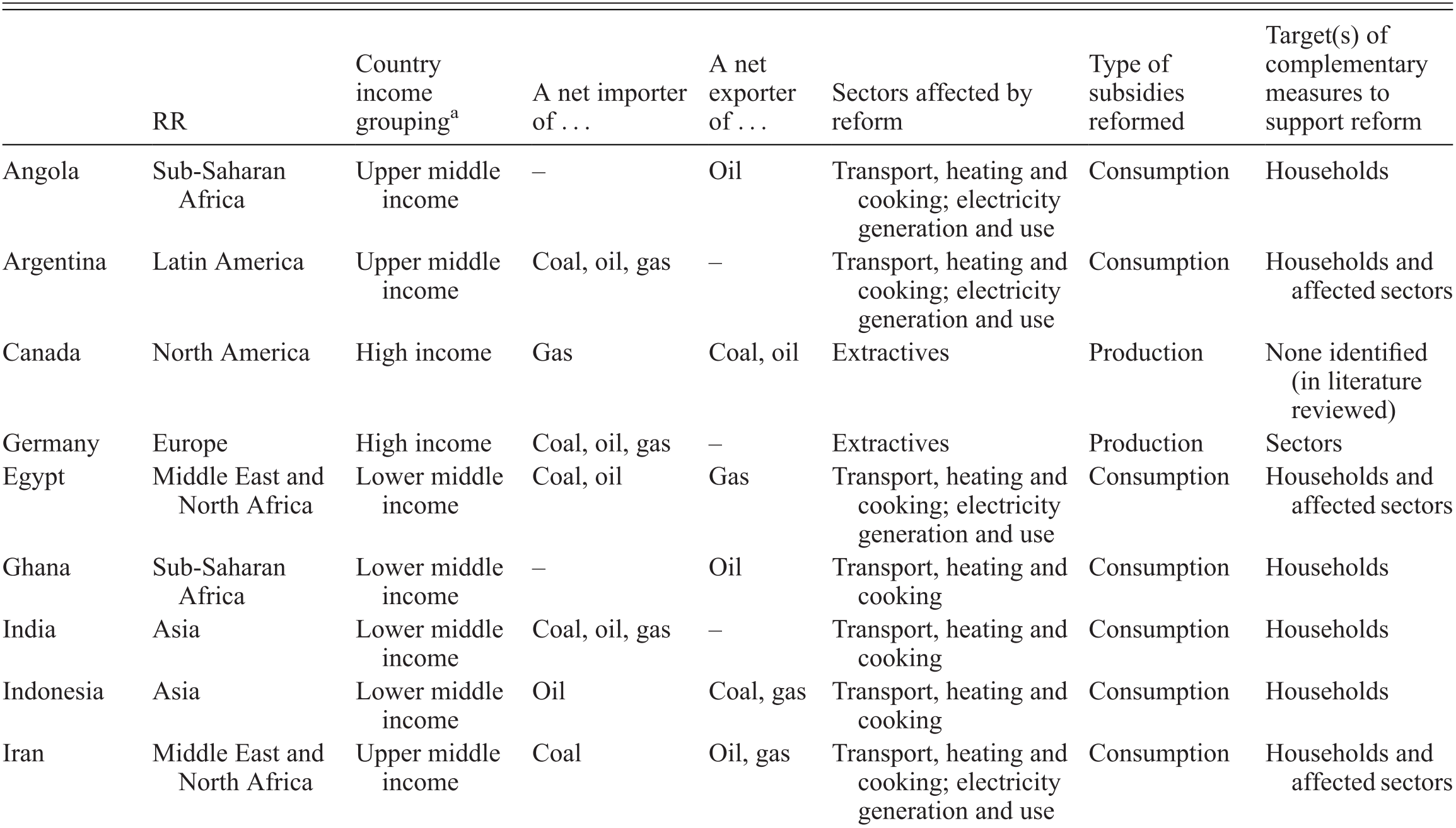

Based on the work of the IMF, World Bank and other international organisations, Table 3.1 summarises important fossil fuel subsidy reforms across a range of countries and sectors, highlighting drivers that are relevant to different national contexts.

Table 3.1 Summary of case studies of fossil fuel subsidy reform

| RR | Country income groupinga | A net importer of … | A net exporter of … | Sectors affected by reform | Type of subsidies reformed | Target(s) of complementary measures to support reform | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | Sub-Saharan Africa | Upper middle income | – | Oil | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households |

| Argentina | Latin America | Upper middle income | Coal, oil, gas | – | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households and affected sectors |

| Canada | North America | High income | Gas | Coal, oil | Extractives | Production | None identified (in literature reviewed) |

| Germany | Europe | High income | Coal, oil, gas | – | Extractives | Production | Sectors |

| Egypt | Middle East and North Africa | Lower middle income | Coal, oil | Gas | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households and affected sectors |

| Ghana | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income | – | Oil | Transport, heating and cooking | Consumption | Households |

| India | Asia | Lower middle income | Coal, oil, gas | – | Transport, heating and cooking | Consumption | Households |

| Indonesia | Asia | Lower middle income | Oil | Coal, gas | Transport, heating and cooking | Consumption | Households |

| Iran | Middle East and North Africa | Upper middle income | Coal | Oil, gas | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households and affected sectors |

| Mexico | Latin America | Upper middle income | Coal, gas | Oil | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Affected sectors |

| Nigeria | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income | – | Oil, gas | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households and affected sectors |

| Peru | Latin America | Upper middle income | Coal, oil | Gas | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | None identified |

| Tunisia | Middle East and North Africa | Upper middle income | Oil, gas | – | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households |

| Turkey | Europe | Upper middle income | Coal, oil, gas | – | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | Households and affected sectors |

| United Arab Emirates | Middle East and North Africa | High income | Coal, gas | Oil | Transport, heating and cooking; electricity generation and use | Consumption | None identified |

a According to World Bank country and lending groups classification (World Bank 2017).

3.4 Key Principles for Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

A growing body of policy recommendations based on past experiences highlights different important factors for robust subsidy reform (across all sectors). While there is no single recipe for success, the prospects for sustained reforms can be enhanced by adherence to basic principles and by recognising national circumstances and changing regional and international market conditions.

Because subsidies are mainly provided at the national and sub-national levels, reform guidance must be country or context specific. Specific elements of a subsidy reform process contribute to its effectiveness and sustainability, as observed during the subsidy reform in some countries and as outlined in policy recommendations from international organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as the Global Subsidies Initiative. These elements are a ‘whole-of-government’ approach, research and analysis, consultation and communication, mobilising resources, complementary measures (for sectors and households), phasing in and linking to wider reform processes.

3.4.1 Whole-of-Government Approach

Efforts to reform fossil fuel subsidies might, at first glance, seem relevant to only one subsector and one energy department or ministry. However, the importance of energy for the economy and the impact of subsidies on wider economic, environmental and social objectives justify a whole-of-government approach. The OECD has also found that individual government ministries lack access to the tools required to mitigate the impacts of higher energy prices, support economic diversification or convene reform processes (OECD 2007). Thus, coalitions that include key ministries and agencies at the national and sub-national levels are more likely to succeed (see also Chapter 12).

Such processes are also needed to bring together the many relevant agencies and to avoid sending conflicting signals to the public and businesses (Vis-Dunbar Reference Vis-Dunbar2014). In the Dominican Republic and Honduras, for example, joint action by public actors across the government, rather than just one or two ministries, was seen as essential for creating broad political ownership of reform (Gamez Reference Gamez2014; Toft Reference Toft2015).

3.4.2 Research and Analysis

Governments and other stakeholders should conduct research and analysis before, during and after subsidy reform. The resulting findings should inform communication and consultation processes and provide evidence to support cross-government collaboration and resource mobilisation. Several contributions to this book (e.g. Chapters 2, 11, 13, 15 and 16) point to awareness of fossil fuels being subsidised as a key factor influencing whether fossil fuel subsidies can be successfully reformed. In many cases, the selection of who should complete this research and analysis, and how, may be as important as the resulting analysis. For example, a supportive review of subsidy reform written by a member of the industry benefiting from the subsidy – and in consultation with relevant stakeholders – may be more influential than a report by an academic institution or government body (OECD 2007).

The process of data collection needs to recognise the limits to the scale of analysis that can be undertaken and implemented, that hard evidence alone is not sufficient to enable and sustain reform and that some information collected can also be used to support reforms for carbon pricing (OECD 2007).

3.4.3 Consultation Before, During and After Reform

Any subsidy reform process must be supported by transparent and extensive communication and consultation with stakeholders, including the general public. There is strong evidence on the need for clear and honest messages on the scale of subsidies, their costs and impacts, the plans for reform and any complementary measures (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Coady and Fabrizio2013; IEA 2014). Both consultation and communication are critical to dispel myths about subsidies, correct information asymmetries, build coalitions for reform, improve participation in collective efforts and get the support of those resistant to change (OECD 2007; Aldahdah Reference Al-Dahdah2014; see also Chapter 15).

Broad stakeholder consultation and engagement are important for durable reform and to ensure that reforms are perceived as fair and legitimate reflections of citizens’ preferences (IEA 1999; OECD 2006, 2007). Alliance building may mean engaging unlikely allies, such as well-performing segments of sectors or regions, to offset those lobbying against reforms (OECD 2006).

Stakeholder groups are diverse and go beyond government officials to include industry associations, companies, trade unions, consumers, political activists and civil society organisations. All must be involved if subsidies are to be eliminated. Reform efforts may originate from, or can be supported by, international organisations and civil society organisations, which can increase interest and participation in reform processes (OECD 2006; see also Chapters 6 and 10).

Communication about subsidies and reforms should be tailored to different audiences and use a range of channels, such as television, radio, digital media, direct engagement and print. Malaysia’s reform processes, for example, included a public forum on fossil fuel subsidies, a public survey on whether and when subsidies should be reduced, YouTube videos on the country’s fuel subsidies, a Twitter account for announcements and answering questions from the public and the engagement of public figures to write about the issue in the media (Vis-Dunbar Reference Vis-Dunbar2014; Fay et al. Reference Fay, Hallegatte and Vogt-Schilb2015). Reform processes in Indonesia included text messages explaining the new subsidy policy, and in the Philippines reform efforts included a nationwide roadshow.

Civil society organisations can play an important role here. For example, the Global Subsidies Initiative has supported subsidy reform efforts in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Nigeria by publishing citizens’ guides to fossil fuel subsidies, written in accessible language to increase public understanding (e.g. IISD 2012; see also Chapter 10).

It is also essential to develop metrics to measure the overall impact of media and communications outreach. Surveys and polls provide insights into current habits, and follow-up surveys reveal whether these have changed (Vis-Dunbar Reference Vis-Dunbar2014). Such surveys can also be paired with wider government efforts to monitor the impacts of subsidy reform, aiming to support sustainability, so that policies are not reversed and subsidies are not re-introduced (Whitley and van der Burg Reference Whitley and van der Burg2015; van der Burg and Whitley Reference van der Burg and Whitley2016). The aim should be to demonstrate the progress made towards the desired goals of subsidy reform and to monitor and disseminate information on the use of the fiscal space created by reforms. Surveys should also offer transparent and up-to-date information on the costs of any remaining subsidies.

3.4.4 Mobilising Resources Before and During Reform

While subsidy reform can generate fiscal space and additional government revenue that far exceeds upfront costs, these positive impacts on government budgets are felt only after reforms have been implemented (Koplow Reference Koplow, Halff, Sovacool and Rozhon2014). As a result, most governments need to mobilise resources – both domestically and internationally – before reform to support the elements necessary for a robust reform process (see Chapters 6 and 12). This is crucial to cover the costs of analysis, communication, consultation, complementary measures and institutional reforms that are needed before wider subsidy reform processes. Recent reforms in Indonesia illustrate the need for upfront finance; it used the 2014 state budget to fund its reform process, reserving the savings from reform for later complementary measures (Lontoh Reference Lontoh2015).

3.4.5 Complementary Measures

Although the benefits of fossil fuel subsidies accrue mostly to the wealthy, the adverse impact of subsidy removal can fall disproportionately on the poor. Income groups differ greatly in their energy consumption patterns, and the distributional impact of subsidies – or their removal – is not the same for all types of fuel and electricity. On average, poorer households (particularly in urban areas) spend a higher proportion of their energy budget on fuel, particularly for cooking, and less on electricity and private transport (IEA et al. 2010).

As a result, the poor are affected directly by the rising prices that result from subsidy reform and indirectly through the increased cost of transport and food (IEA et al. 2010). The implementation of measures to mitigate these likely negative impacts increases the likelihood of successful fossil fuel subsidy reform. In several countries, poor households may represent a large proportion of the population, and a key element of successful reform is the efficient and visible reallocation of resources to those most affected (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Coady and Fabrizio2013).

Complementary measures (including new subsidies) can be developed through resources mobilised before reforms and resources saved or generated by removing fossil fuel subsidies. The efficient use of these resources as part of well-designed and clearly communicated complementary measures increases the likelihood that reform processes will be successful and sustained. However, economies evolve constantly, and it is impossible to safeguard all parts of society from all negative consequences (OECD 2007).

The following sections provide specific guidance for complementary measures directed towards sectors and households affected by fossil fuel subsidy reform. While any given measure may target one affected group, the benefits will spill over to others; for instance, job creation supports sectors as much as households.

3.4.5.1 Sectors, Industries and Firms

Fossil fuel subsidies often become embedded in the operations of sectors, industries and firms, which may engage in coalitions opposed to, or in favour of, subsidy reform (see Chapter 1). As a result, any reform process can gain political support only if it is designed to allow these groups to adapt to new economic circumstances. While support is required for the growth of new sectors, the rapid economic transition needed for decarbonisation requires active government policies to smooth the decline of old sectors (Fay et al. Reference Fay, Hallegatte and Vogt-Schilb2015).

These measures can include incentives to diversify the regional economic base, infrastructure development, assistance with business restructuring and adoption of alternative technologies, initiatives for retraining and relocation, unemployment insurance and support for early retirement (OECD 2007). If these can be developed through existing social security systems, it can reduce costs and simplify administration. When this is not possible, the development of new institutions and systems may be required and could be linked to support at the household level (OECD 2007).