5.1 Introduction

The idea of fossil fuel subsidy reform can be considered an ‘international norm’, usually defined as a ‘standard of appropriate behaviour’ (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 891). Norms define what actors ought and ought not to do – respect human rights, for example, or ban chemical weapons. Contrary to binding laws and rules, norms are obeyed not (necessarily) because they are enforced but because they are seen as legitimate and contain a sense of ‘oughtness’ (Florini Reference Florini1996). This description captures fossil fuel subsidy reform quite well, as state support for fossil fuels is increasingly portrayed as deviant from ‘proper’ or ‘appropriate’ behaviour. Lord Nicholas Stern (2015), for example, called low taxes on coal consumption ‘unethical’ because they result in large-scale deaths and damage to others. Similarly, Fatih Birol, now the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA), declared that fossil fuel subsidies ‘do not make sense’ and are ‘public enemy number one’ (cited in Casey Reference Casey2013).

Looking at fossil fuel subsidy reform through the lens of international norms raises two questions. First, international norms are typically the products of advocacy by transnational networks and social movements (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). The fossil fuel subsidy reform norm, however, did not follow this traditional pattern. Instead, it more or less trickled down from above in 2009, when the leaders of the Group of 20 (G20) pledged to ‘phase out over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies’ (G20 2009). The very few non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that had worked on the issue were completely taken by surprise by this G20 commitment. How can we account for the top-down emergence of the fossil fuel subsidy reform norm in the absence of a networked international ‘movement’ led by transnational norm entrepreneurs? And why did the norm emerge in the late 2000s, even though the first calls for reform of fossil fuel subsidies can be traced back to the 1980s?

Second, the weak diffusion of the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform is also puzzling. In spite of the commitment to phase out fossil fuels at the highest possible political level (the leaders of the G20), many states inside and outside the G20 continue to provide lavish support to fossil fuel consumers and, to a lesser extent, producers. Moreover, the issue has been generally overlooked in the international climate change regime (van Asselt and Kulovesi Reference van Asselt and Kulovesi2017; see Chapter 8). The absence of real action within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) regime on fossil fuel subsidies is surprising given that fossil fuel subsidies can be regarded as a form of ‘negative climate finance’ (Brende Reference Brende2015) or even an ‘anti-climate policy’ (Compston and Bailey Reference Compston and Bailey2013). An efficient climate policy would first seek to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies and then explore ways to price carbon, yet international efforts have focused primarily on ways to price carbon, arguably putting the cart before the horse.

This chapter seeks to explain the top-down emergence and incomplete diffusion of fossil fuel subsidy reform as an international norm. Our focus lies on the international level. We first trace the long history of multilateral efforts to address fossil fuel subsidies, before interpreting the role of norm entrepreneurs, political opportunity structures and discursive contestation. A key conclusion that emerges from this is that the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform remains essentially contested. In contrast to the established international consensus over how to define agriculture and fisheries subsidies, no common definition of energy subsidies has emerged, which hinders implementation of the norm. The norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform thus follows a broader pattern, recently identified by constructivist norm scholars, whereby very general norms have weak normative power because they permit a very wide range of interpretations. This often leads to their decay or irrelevance (e.g. Bailey Reference Bailey2008; Hadden and Seybert Reference Hadden and Seybert2016).

5.2 Genesis of the Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform Norm

How did the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform emerge? Here we describe the process of how international norms emerge along three stages. In the first stage, a norm is articulated by a set of norm entrepreneurs. In this process of norm building, norm entrepreneurs call attention to issues and set new standards of appropriate behaviour. In the second stage, the norm gets institutionalised in specific sets of international rules and organisations. This happens when norm entrepreneurs convince a critical mass of states (norm leaders) to embrace the new norm. The third stage involves the diffusion of the international norm as the norm leaders attempt to socialise other states to become norm followers.

Our three-staged model is inspired by the seminal work of Finnemore and Sikkink (Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998), but it also differs from their model because we do not assume that these stages unfold in a strictly sequential manner. Some norms may indeed ‘cascade’ through the international system and eventually reach the stage of internalisation. This is the point where the norm gets a taken-for-granted character and is no longer a matter of broad public debate. For example, few people today would dispute the abolishment of slavery or the immunity for medical personnel during war (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998). Other norms fare less well and may be subject to backsliding, reinterpretation, replacement and even complete disappearance.

Therefore, rather than seeing the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform as a concept with a fixed meaning that evolves linearly, we subscribe to the more constructivist position of norms as ‘processes’ or as works in progress that have contested and shifting meanings. Norms are often agreed to in international treaties and organisations precisely because they mean different things to different actors (Wiener Reference Wiener2008; Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010; Bucher Reference Bucher2014). The articulation of the fossil fuel subsidy reform norm (e.g. determining which fossil fuel subsidies are ‘inefficient’) may continue well after the norm has been embraced in an international forum (e.g. the G20). The three stages laid out in the remainder of this section thus should be seen as overlapping and not as strictly separate or sequential.

5.2.1 Norm Articulation

There is a long history of international efforts to reform fossil fuel subsidies, but attention to the issue has waxed and waned over time, and the policy goals and justifications have shifted considerably. The first major multilateral effort to address energy subsidies was the 1951 Treaty Establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to the European Union. This treaty expressly abolished and prohibited all ‘subsidies or aids granted by States’ to the coal sector, which were deemed ‘incompatible with the common market for coal’ (ECSC Treaty 1951: Article 4). However, since 1965, given the severe problems in this industry, exemptions from that rule became routine (Steenblik Reference Steenblik1999).

The 1980s was the first decade during which energy subsidies began to be scrutinised by NGOs and international organisations (World Bank 1982, 1983; Kosmo Reference Kosmo1987; IEA 1988). The global context was characterised by the rise of neoliberal ideology, with its emphasis on liberalisation, fiscal discipline and redirection of public expenditures. Against this backdrop, initial studies on energy subsidies emphasised their macroeconomic, fiscal and public revenue effects, rather than their environmental effects. A 1987 World Resources Institute study only briefly touched on the environmental consequences of energy subsidies while covering the macroeconomic and microeconomic effects to a much larger extent (Kosmo Reference Kosmo1987). The so-called Washington Consensus spread to developing countries through the Structural Adjustment Programmes of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. As a result, energy consumption subsidies were reduced in most of the newly emerging countries of Central and Eastern Europe, and several African and Asian countries partially or completely deregulated their fuel prices in the 1980s and 1990s (Steenblik Reference Steenblik and Pauwelyn2009: 188).

As environmental issues were increasingly capturing global attention, a World Bank study for the first time calculated the potential carbon dioxide emission reduction gains from subsidy removals (Larsen and Shah Reference Larsen and Shah1992). The report caught the attention of the Group of 7 (G7) environment ministers in 1994, who recommended reducing ‘the currently high volume of environmentally damaging subsidies in the industrialised and in the developing countries’ (G7 1994a). This statement was noteworthy because fossil fuel subsidy reform was no longer solely justified on fiscal (economic) grounds but also on climate change (environmental) grounds. More importantly, industrialised states acknowledged that they had environmentally damaging subsidies in place. Yet, at the subsequent G7 leaders’ meeting in Naples, this issue was not raised in the final communiqué (G7 1994b).

Attention to the issue of energy subsidies waned until the IEA decided to make it a key focus of its 1999 World Energy Outlook (IEA 1999). The IEA noted that ‘very few detailed quantitative estimates exist of the true costs of energy subsidies’ and that ‘information is particularly poor for developing countries, which are projected to contribute two-thirds of the world’s incremental energy demand in the next twenty years’ (IEA 1999: 9). In other words, pricing distortions were emerging as a key uncertainty in the outlook for energy demand growth and were hence complicating the IEA’s mission to develop global energy scenarios. The IEA framed the issue of energy subsidies in terms of both public spending and environmental stewardship. The report received a lot of press, and the IEA decided to continue working on this issue.Footnote 1

It is remarkable to see how, from the very beginning, there have been different articulations of the norm. In fact, the norm has never been consistently defined or measured. In its 1988 study of coal subsidies, the IEA applied the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) producer-support estimate approach (IEA 1988). Larsen and Shah (Reference Larsen and Shah1992) of the World Bank combined the price-gap approach with elasticities to estimate the welfare and environmental costs of energy subsidies. More recent work by the IMF (Coady et al. 2015a) even frames the absence of Pigouvian taxes on negative externalities as a subsidy.Footnote 2 The lack of a common definition of energy subsidies meant that the ongoing work in the 1980s and 1990s was piecemeal and largely non-cumulative. Most studies were done in the form of case studies, but since each started from a different definition and followed a different format, the findings were not comparable across the cases. The upshot is that, today, ‘nobody refers back to that work’.Footnote 3 The lack of consensus over what fossil fuel subsidies are, and how they should be measured, continues to fuel norm contestation to this very day (see Chapter 2).

5.2.2 Norm Institutionalisation

Bernstein (Reference Bernstein2001: 30) defines ‘norm institutionalisation’ as the ‘perceived legitimacy of the norm as embodied in law, institutions, or public discourse even if all relevant actors do not accept or follow it’. It can be inferred primarily from ‘the norm’s frequency or “density” in social structure, that is, the amount and range of instruments, statements, and so on, that invoke the norm’ (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2001: 30).

The institutionalisation of the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform received a shot in the arm in 2009 when the G20 leaders pledged to rationalise and phase out fossil fuel subsidies at their Pittsburgh summit (G20 2009). A few months later, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) countries adopted a similar voluntary commitment (APEC 2009), which added 11 new countries to the group committing to the phase-out. While a number of NGOs and international organisations had raised the issue before, many of them were surprised that the G20 took up the issue. Leadership by the Obama administration and the wider context of the global financial crisis were instrumental in getting the issue onto the G20’s agenda (see Section 5.3). The G20 and APEC endorsements of fossil fuel subsidy reform arguably represented what Finnemore and Sikkink (Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998: 901) call the ‘tipping point’: the moment ‘at which a critical mass of relevant state actors adopt the norm’.

By committing in 2009 to phase out ‘inefficient’ fossil fuel subsidies over ‘the medium term’ and by reiterating the commitment every year until 2016, the G20 set in motion a process whereby the fossil fuel subsidy reform campaigners gained a larger supporting constituency. To implement its strategy, the G20 asked four relevant institutions – the IEA, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, the OECD and the World Bank – to ‘provide an analysis of the scope of energy subsidies and suggestions for the implementation of this initiative’ (G20 2009). Several follow-up reports were commissioned, ensuring that the issue of fossil fuel subsidies gained primary attention in those organisations as well. Not only international organisations but also national finance and energy ministries started addressing the issue of fossil fuel subsidy reform when the G20 countries were asked to prepare national reports on fossil fuel subsidies.

The fossil fuel subsidy reform norm gradually made its way into the United Nations (UN) sphere and was included in the final reports of the Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing (2010), the High-Level Panel on Global Sustainability (2012), and the Third Financing for Development Conference (2015). Prior to the UN Rio+20 Conference (2012), there was a huge push from NGOs to make fossil fuel subsidy reform the lead issue within the energy goal of the new Sustainable Development Goals, but the issue was too contentious. In the end, fossil fuel subsidy reform was moved from Goal 7 (on Secure, Sustainable Energy) to Goal 12 (on Sustainable Production and Consumption), where it was mentioned as a possible means of implementation. For NGOs like the Global Subsidies Initiative, this represented a step backwards, since ‘the wording is no longer a goal, no longer linked to energy, does not include an end date, and is no longer about a phase out’ (Merrill Reference Merrill2014).

Efforts to graft the issue of fossil fuel subsidy reform onto the agenda of global climate negotiations also largely failed. The UNFCCC does not mention fossil fuel subsidies even once, whereas the Kyoto Protocol only includes a vague reference to ‘subsidies in all greenhouse gas emitting sectors’ in an illustrative list of policies and measures, leaving it up to the parties to decide which policies to implement (van Asselt and Skovgaard Reference van Asselt, Skovgaard, Van de Graaf, Sovacool, Ghosh, Kern and Klare2016; see Chapter 8). During the December 2015 climate negotiations in Paris, a proposal urging countries to ‘reduce international support for high-emission investments’ appeared in the penultimate draft text but was cut from the final version (UNFCCC 2015: 6). Countries could refer to fossil fuel subsidy reform as part of their nationally determined contributions, but only 14 countries did so in the run-up to the climate summit in Paris (Terton et al. Reference Terton, Gass, Merrill, Wagner and Meyer2015).

Despite these setbacks at the United Nations, a few months later the leaders of the G7 pledged to ‘remain committed to the elimination of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies and encourage all countries to do so by 2025’ (G7 2016). This was the first commitment related to fossil fuel subsidy reform that included an implementation date. At the subsequent G20 Hangzhou summit in September 2016, the first voluntary peer reviews were presented of the reform efforts of China and the United States (G20 2016). Two other members, Germany and Mexico, volunteered to be next subjected to peer review. Their reviews were presented in November 2017.

5.2.3 Norm Diffusion

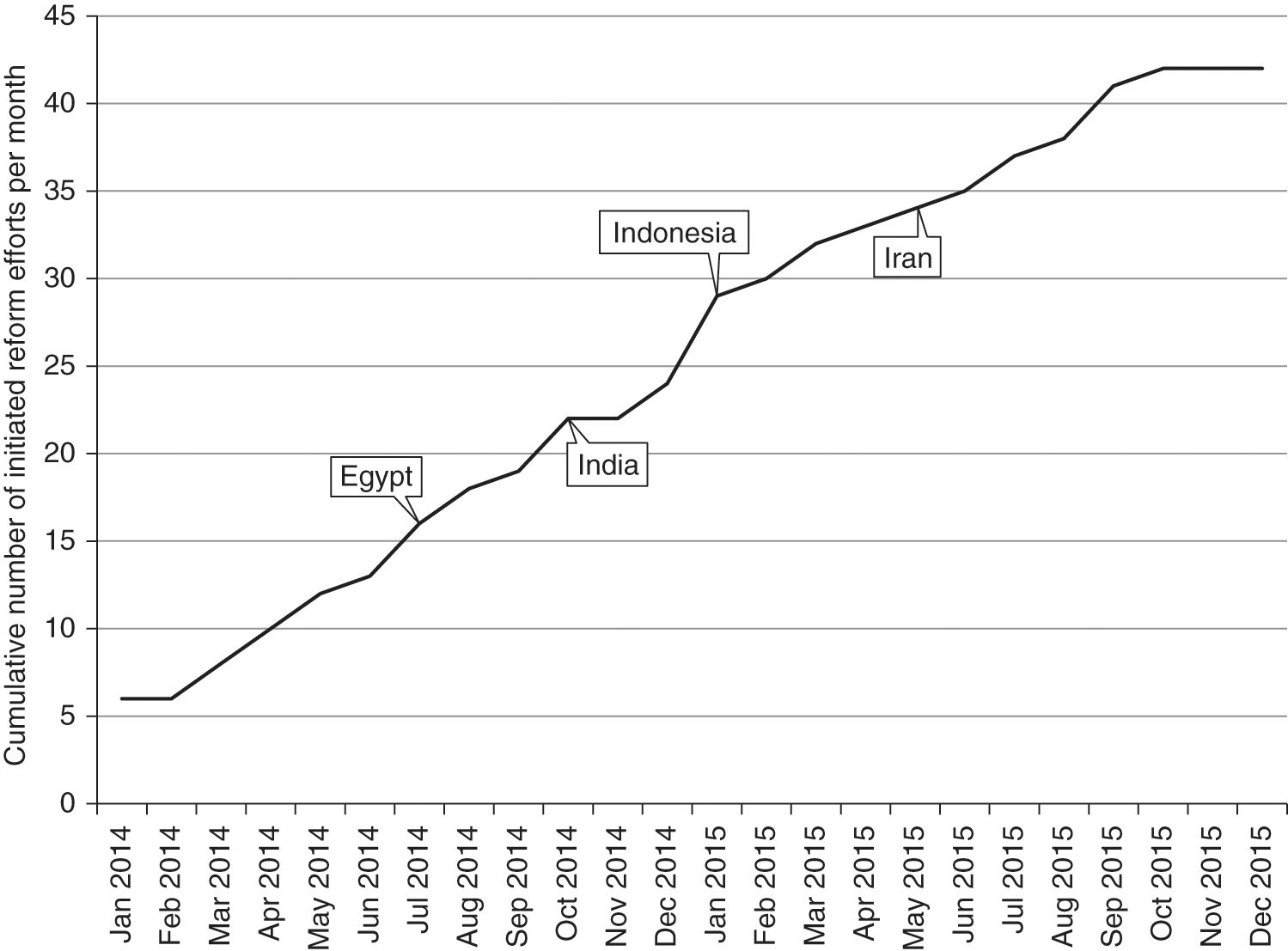

Over the past few years, numerous countries have initiated fossil fuel subsidy reform to some degree, as documented in various chapters in this book. In 2014 alone, almost 30 countries implemented fossil fuel subsidy reform (Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Harris, Casier and Bassi2015), including countries such as Ukraine and Saudi Arabia that had no (recent) history of attempted reforms. Whether these reforms will stick if crude oil prices rise again remains to be seen, as there are many historical examples of countries reversing reforms. Yet the impact of the implemented reforms in the wake of the G20 commitment is real and tangible. The IEA has calculated that without the national reforms undertaken since 2009, the value of fossil fuel consumption subsidies would have been 24 per cent higher in 2014, putting the level of these subsidies at USD 610 billion instead of USD 493 billion (IEA 2015: 96–97).

Figure 5.1 shows the cumulative monthly number of initiated reform efforts in the period 2014–15. This figure was compiled using data from the IEA (2015) and the Global Subsidies Initiative. There are four important considerations to keep in mind. First, since the figure counts reform efforts, countries can appear more than once. Iran, for example, raised gasoline prices by 75 per cent in April 2014 and then by another 25 per cent in May 2015. These reforms are counted separately. Second, the figure only counts initiated reform efforts and does not trace whether or not the reforms have been sustained. Third, the figure shows that there is a wave of countries initiating reforms, including large countries such as India, Indonesia, Nigeria and Egypt, which are highlighted on the chart. However, it is hard to tell whether the global pace of fossil fuel subsidy reform has accelerated after 2009 due to the lack of adequate and comparable historical data. International organisations have only recently started to compile databases of fossil fuel subsidies. The IEA’s fossil fuel subsidy database, for example, only goes back to 2012. Fourth, measuring energy subsidies is also hampered by the varying definitions of what constitutes a subsidy and different ways of measuring them. The bulk of subsidy reforms reported here was calculated with the price-gap method (see Chapter 2).

It is clear that fossil fuel subsidies are still widespread, even in many G20 countries. The institutionalisation of the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform in global forums thus should not be conflated with genuine norm adoption and internalisation (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998).

5.3 Key Drivers Behind the Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform Norm

The concept of fossil fuel subsidy reform rarely came up until 2005, but in recent years more than 40 efforts to reform fossil fuel subsidies have been initiated. What explains the emergence of fossil fuel subsidy reform as an international norm? Drawing on recent scholarship on international norms (Wunderlich Reference Wunderlich, Wunderlich and Müller2013), we highlight the role of norm entrepreneurs, political opportunity structures and discursive contestation in shaping the emergence and uneven diffusion of the fossil fuel subsidy reform norm.

5.3.1 Norm Entrepreneurs

There is a large consensus in the literature that ‘norm entrepreneurs’ play a key role in both the emergence and further development of norms (Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998; Bucher Reference Bucher2014). Norm entrepreneurs may operate from organisational platforms such as NGOs, transnational advocacy networks or standing international organisations that have their own distinct purposes and agendas. Norm entrepreneurs can therefore be non-state as well as state actors (Wunderlich Reference Wunderlich, Wunderlich and Müller2013: 33).

The fight against energy subsidies was spearheaded in the 1980s by NGOs (most notably the World Resources Institute) and international organisations (particularly the IEA and the World Bank). These actors and institutions all contributed to placing fossil fuel subsidy reform on the global agenda. Between 2005 and 2009, the issue had been addressed by several NGOs, including Oil Change International and Earth Track, mostly from a climate change perspective. In 2005, the Global Subsidies Initiative was established within the International Institute for Sustainable Development, the first NGO to focus squarely on the issue of subsidy reform (see Chapter 10). Fossil fuel subsidy reform was a central part of the Global Subsidies Initiative’s long-term strategy, set out at a meeting in the margins of the December 2005 World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Meeting in Hong Kong. Yet, in its early days, the Global Subsidies Initiative focused mostly on biofuel and irrigation subsidies. The newly created NGO wanted to ‘cut its teeth first on subsidies that few were addressing before taking on the much larger and challenging subject of fossil fuel subsidies’ (Steenblik Reference Steenblik2016).

It is hard to overstate the role of the Obama administration in promoting the fossil fuel subsidy reform norm on the international stage. The September 2009 G20 Pittsburgh Summit was the first chance for the newly elected US President Barack Obama to host and chair a summit and thus make history at home on a central world stage. The idea to act on fossil fuel subsidies was pushed by Lawrence Summers, then director of the National Economic Council, who had long opposed such subsidies. It was presented at the Sherpa meeting only two weeks before the actual summit. The idea was to ‘creatively link climate change to the financial and fiscal issues at the G20 agenda’s core’ (Kirton and Kokotsis Reference Kirton and Kokotsis2015: 229). When the G20 partners did not oppose to the general idea, ‘the Americans seemed pleased and surprised that they had gotten so far with the fossil fuel subsidies initiative’ (Kirton Reference Kirton2013: 302).

Many of the above-mentioned NGOs, including the Global Subsidies Initiative, were caught completely off guard when the G20 made the pledge to phase out fossil fuel subsidies at their Pittsburgh Summit (Chapter 10). Ronald Steenblik, a long-time expert on energy subsidies at the OECD and former research director of the Global Subsidies Initiative, only heard about the G20 pledge one week before the summit.Footnote 4 In other words, NGOs and international organisations did not influence the G20 agenda through direct lobby efforts but may have influenced the G20 agenda indirectly by exerting ideational power – that is, by conveying information, providing advice and identifying new policy options.

The Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (FFFSR), an informal coalition of non-G20 countries led by New Zealand, is helping to sustain momentum on fossil fuel subsidy reform (see Chapter 9).Footnote 5 Established in June 2010, the group advocates for reform through three interrelated principles: increased transparency around fossil fuel subsidies, greater ambition in the scope of reform and the provision of targeted support for the poorest (FFFSR 2015). The FFFSR has organised meetings and summits, published statements and hosted side events at the annual Conferences of the Parties to the UNFCCC, often in cooperation with the Global Subsidies Initiative. The FFFSR group was created in analogy to existing groups of like-minded WTO members – such as the Friends of Fish, Friends of Special Products and Friends of Anti-Dumping Negotiations – that act as informal negotiation coalitions within the WTO or other international trade, development or environment contexts. The FFFSR group appears to be largely focusing on the reform of consumption subsidies (a problem largely for developing countries) rather than on production subsidies (recurrent in both developing and industrialised countries).

5.3.2 Political Opportunity Structures

Agents do not exist in a vacuum but instead operate in shifting contexts. The importance of these settings is captured by the term ‘political opportunity structures’, generally referring to the nature of resources and constraints that are external to norm entrepreneurs. Particularly important exogenous factors are crises and so-called focusing events. A crisis situation usually leads policymakers to question conventional policy wisdom and thus opens a window of opportunity for new policy ideas. Norm entrepreneurs can capitalise on the opportunity by framing the policy issue at hand in a new way (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993).

The G20 Pittsburgh Summit, organised in the midst of a global financial and economic meltdown, primarily addressed the critical transition from global crisis to recovery. It focused on turning the page on an era of ‘irresponsibility’ by adopting a set of reforms through the G20 Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth (G20 2009). The financial crisis led global leaders to rethink embedded wisdoms on economic growth, thus creating a political window of opportunity for fossil fuel subsidy reform to be grafted onto the global sustainable-development agenda. The G20, under the auspices of President Obama, pushed for ‘sustained and systematic international cooperation’ and a ‘credible process for withdrawing extraordinary fiscal, monetary and financial sector support’ (G20 2009). The crisis proved to be a useful window of opportunity in political terms to advocate for fossil fuel subsidy reform based on a convergence of fiscal, macroeconomic, distributive and environmental arguments.

Another important contextual factor is the international price of oil. Albeit economically inefficient, energy subsidies provide economic benefits to actors who consume fossil fuels and producers who extract them. Interest groups that demand subsidies are mostly well organised, while simultaneously the beneficial effects of these subsidies strengthen these interest groups’ awareness of their need to sustain policy subsidies (Victor Reference Victor2009: 7). Here it is important to differentiate between consumer and producer subsidies: consumer subsidy reform is easier when oil prices are low. Under low oil prices, such as in the period between 2014 and 2016, the economic and political costs of consumption subsidy cancellation or reform are less severe than under high oil prices. As a result, ‘a rational interest group that benefits from fuel subsidies lobbies less aggressively for their continuation when oil prices decrease’ (Benes et al. Reference Benes, Cheon, Urpelainen and Yang2015: 10). Reform of producer subsidies, by contrast, should in theory be easiest when prices are high, as they were between 2010 and 2014.Footnote 6 When fossil fuel prices are low, we would expect producers to lobby harder for their subsidies because they account for a higher relative share of their net profits due to the lower prices for their products.

5.3.3 Discursive Contestation

The third driving force of the dynamic evolution of norms is ‘discursive contestation’. In constructing their cognitive frames, norm entrepreneurs face opposition from firmly embedded norms and frames that create alternative perceptions of both appropriateness and interest (‘external contestation’). For example, fossil fuel subsidies are still often represented as social policy, helping to bring energy services to the poor, particularly in rural areas. They have also been justified on the grounds of redistributing national wealth, fostering energy security or promoting economic development by supporting energy-intensive industries (Commander Reference Commander2012; Strand Reference Strand2013). Supporters of fossil fuel subsidy reform counter these arguments by pointing to the fiscal, economic, environmental and distributional costs of fossil fuel subsidies (Coady et al. Reference Coady, Flamini and Sears2015b; Rentschler and Bazilian Reference Rentschler and Bazilian2017). They argue that governments may reap political benefits from offering a salient and visible bonus to their citizens (Victor Reference Victor2009).

There can also be contestation among the supporters of the norm themselves (‘internal contestation’), often on matters of definition (Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010; see also Chapter 2). Such controversy usually plays out in the form of ‘frame contests’, whereby actors promote competing discourses that differ in how they make sense of different situations and events, attribute blame or causality and suggest lines of action (Schön and Rein Reference Schön and Rein1994). Critical constructivist scholars argue that such norm contestation is a permanent feature of any normative system (Wiener Reference Wiener2008).

The vague description of fossil fuel subsidies at the G20 Pittsburgh Summit demonstrates that framing an international norm is a highly strategic process. The concept of fossil fuel subsidy reform was not defined in the summit’s outcome document, and no specification was given to the terms ‘rationalise’, ‘medium term’ and ‘inefficient’. If a detailed definition had been given, many countries would have probably not accepted the Pittsburgh pledge to phase out fossil fuel subsidies. The BRICs group (Brazil, Russia, India and China), with India as their agent, succeeded in including the word ‘rationalise’ in the commitment (Kirton and Kokotsis Reference Kirton and Kokotsis2015: 230). Saudi Arabia was less successful when it tried to replace the term ‘fossil fuel subsidies’ with the more generic ‘energy subsidies’, thus targeting, among other things, subsidies for biofuels. After the summit, Saudi Arabian authorities were quick to claim that the country’s subsidies were not ‘inefficient’ and therefore should not be subject to reform (Lahn and Stevens Reference Lahn and Stevens2011: 12–13).

Many G20 countries made a similar argument in their reports submitted after Pittsburgh. Of the 20 member countries, eight stated that they had no ‘inefficient’ fossil fuel subsidies that needed to be phased out, including two (the United Kingdom and Japan) that provided no information at all.Footnote 7 The number of countries opting out of reporting entirely tripled from two in 2010 to six in 2011 (Van de Graaf and Westphal Reference Van de Graaf and Westphal2011). The emerging norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform is thus a perfect illustration of the argument that the institutionalisation of norms in international forums and treaties should not be conflated with the genuine adoption of the norm. The success of international agreements or conventions often depends on the impreciseness of their content, or as Wiener (Reference Wiener2004: 198) puts it, ‘detail is not necessarily conducive to agreement.’ A broad and often imprecise formulation fosters a broader adoption of the norm precisely because the norm means different things to different people. Therefore, it maximises the potential for consensus but complicates the task of determining what types of behaviour constitute a violation of the norm (Krook and True Reference Krook and True2010: 110).

There is not just disagreement over what constitutes a fossil fuel subsidy but also over how to best measure its different elements (IISD 2014). The IEA follows the above-mentioned ‘price-gap approach’ in defining energy subsidies as ‘any government action that concerns primarily the energy sector that lowers the cost of energy production, raises the price received by energy producers or lowers the price paid by energy consumers’ (IEA 2006: 1). The OECD, by contrast, follows the ‘inventory approach’ and defines ‘energy subsidies’ (or ‘support’ as it prefers to call them) as ‘[a] result of a government action that confers an advantage on consumers or producers [of energy], in order to supplement their income or lower their costs’ (OECD 2010: 191). This definition is based on the WTO’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, according to which a subsidy only exists when it confers a benefit to a specific party, and is meant to be consistent with the OECD’s treatment of government support to agriculture and fisheries. The OECD recognises the fossil fuel consumption subsidies measured by the IEA as an important component of total support to fossil fuels, but it does not measure such subsidies itself because to do so would constitute a duplication of effort. Thus, the OECD views its estimates as complements to those of the IEA, its sister organisation.

The lack of a consensus over the definition and measurement of energy subsidies is not merely a technical matter but a deeply political one. It translates into hugely varying estimates of the size of energy subsidies, ranging from USD 325 billion (IEA 2016) to USD 5.3 trillion in 2015 (Coady et al. Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and Shang2015). These diverging estimates obviously convey different messages about the magnitude and urgency of the policy issue at hand and what kinds of reform (if any) are recommended. The disagreement over what should be counted and how is thus an inherently value-laden exercise (Van de Graaf and Zelli Reference Van de Graaf, Zelli, Van de Graaf, Sovacool, Ghosh, Kern and Klare2016). The IEA’s estimate of USD 325 billion covers most consumer subsidies, which are especially rampant in non-OECD countries, but it leaves out production subsidies, which might actually contribute to the energy security of the IEA’s member governments, still the agency’s primary objective. Economists at the IMF typically frame energy subsidies in terms of fiscal stability, which is related to the organisation’s core tasks, but their estimates also factor in various externalities, such as climate change, air pollution, and traffic congestion. In WTO terms, subsidies are only relevant insofar as they are trade distorting because that could make them legally actionable. In sum, when actors define energy subsidies differently, they construct different policy problems according to their value stance.

5.4 Conclusion

This chapter has examined the drivers behind the development of fossil fuel subsidy reform as an emerging international norm. Our analysis reveals that the initial articulation of the fossil fuel subsidy reform norm can be clearly linked to specific norm entrepreneurs. The anti-subsidies campaign has been backed by an informal coalition of NGOs (most notably the Global Subsidies Initiative, Oil Change International and the World Resources Institute), policymakers (notably the Obama administration) and international organisations and their staff (the IEA, IMF, OECD and World Bank). The Obama administration was probably the most important norm entrepreneur; without its leadership, the norm would have not reached the same level of institutionalisation. The global financial crisis also played a key role in turning the attention of the G20 to fossil fuel subsidy reform.

The norm is also characterised by internal and external contestation and discursive cleavages. Neither the definition of ‘fossil fuel subsidies’, nor the precise meanings of ‘inefficient’ or ‘reform’, have been settled. It has become clear that different alternative framings of the norm coexist, targeting different audiences. Efforts to forge a common definition of fossil fuel subsidies, or a common methodology, among international organisations are likely to falter. However, a division of labour among international organisations may be emerging, such as between the IEA and the OECD, who view their estimates of fossil fuel subsidies as complementary. Such acts of coordination could bring more coherence to the fragmented landscape of international organisations that govern energy subsidies (Van de Graaf and van Asselt Reference Van de Graaf and van Asselt2017).

The availability of more data on fossil fuel subsidies and on how reform strategies can be successfully implemented might in itself spur more countries to enact reforms. To the extent that this happens, the diffusion of the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform may come to rely less on the mechanism of moral persuasion (a communicative process through which actors convince each other that subsidy reform is ‘the right thing to do’) and more on learning (the experience of others provides new information on the effectiveness of policies, leading to an update of causal beliefs) and emulation (the desire of actors to conform to widespread social practices).

Clearly, the fossil fuel subsidy reform norm has not yet reached the stage of being ‘taken for granted’. While this chapter has described the emergence and uneven diffusion of the norm, it did not assess the causal influence of the international norm on actual domestic policy reforms. If countries reformed fossil fuel subsidies in the 1980s and 1990s without referring to it as such and before the norm emerged in the G20, to which degree are the recent domestic reforms the result of the norm being diffused? Future studies could attempt to parse out the effects of the 2009 pledge on the global level of subsidies. In addition, they could look more closely into the causal mechanisms through which fossil fuel subsidy reform as a (contested) norm influences domestic policy processes; for example, it may empower certain constituencies or shift the framing and content of specific reforms.

These questions show that analysing fossil fuel subsidy reform from an international norm perspective opens up a promising area for governance and policy scholars, one that we believe can yield both valuable theoretical and empirical insights.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Laura Merrill, Ron Steenblik and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this chapter.

6.1 Introduction

Over the last decade, fossil fuel subsidy reform has been rising on the agenda of international economic institutions such as the Group of 20 (G20), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). International environmental institutions such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, by contrast, have been rather silent on the issue (see Chapter 8), with the exception of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP 2015). Simultaneously, fossil fuel subsidies are increasingly debated in a number of countries, often leading – particularly in developing countries – to their reform. The question arises whether this correlation indicates a causal influence from the international economic institutions on domestic policies.

A growing body of literature is seeking to identify the role of different political, economic and social factors in fossil fuel subsidies and their reform (Victor Reference Victor2009; Cheon et al. Reference Cheon, Urpelainen and Lackner2013; Lockwood Reference Lockwood2015). Although studies of individual fossil fuel subsidy reforms point to the role of international economic institutions as one factor among many (Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010; Lockwood Reference Lockwood2015), there is no cross-country study of the influence of these institutions. This gap deserves to be addressed due to the impact of these institutions on government policy (Vreeland Reference Vreeland2007). An important aspect of the impact of these institutions is how – or, more precisely, through which causal mechanisms – they influence domestic policy. Whether the institutions have influenced domestic policy via socialisation into norms, learning or more coercive mechanisms of influence (Holzinger and Knill Reference Holzinger and Knill2005; Dobbin et al. Reference Dobbin, Simmons and And Garrett2007) is both academically and politically relevant.

To address these issues, this chapter aims to answer the following research questions: (1) through which causal mechanisms did international economic institutions influence domestic decisions regarding fossil fuel subsidies, and (2) to what extent did these institutions drive or shape fossil fuel subsidy reform?

These questions concern the impact of the G20, the IMF, the World Bank and the OECD on national policies defined as fossil fuel subsidies in Denmark, India, Indonesia, the United Kingdom and the United States. The chapter focuses on the mechanisms of influence rather than the institution from which they emerged, including the intervening causal steps of such influence rather than just the initial source (Heinze Reference Heinze2011: 5). Focusing on mechanisms rather than institutions is more politically relevant, since there is more scope to change the mechanism than the institution. It is also easier to identify and compare the effects of different mechanisms than of different institutions, given that each institution operates via several mechanisms and constitutes an element of an institutional complex (Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Pattberg, van Asselt and Zelli2009), making it difficult to isolate its influence. International organisations are to be understood as constituting one subset of international institutions (Keohane Reference Keohane1989: 3–4).

This chapter first outlines the theoretical framework for studying international influences on domestic policy. It then outlines how this theoretical framework has been operationalised, followed by the application of the framework in the five country cases.

6.2 A Framework for Studying International Influence

This chapter draws on existing frameworks for comparing different mechanisms of influence from the international to the domestic level and identifies three casual mechanisms of influence: ideational, learning and power based (Dobbin et al. Reference Dobbin, Simmons and And Garrett2007; Bernstein and Cashore, Reference Bernstein and Cashore2012). Studying these influences requires a focus on their impact on policy processes and policy debates related to fossil fuel subsidy reform, including the actors within this process and the setting in which they operate (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003). The chapter focuses on influence on the public and policymaking agendas and on policymakers discussing whether and how to reform fossil fuel subsidies (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2003: 2–3). How fossil fuel subsidy reform is carried out is important for its chances of success (Victor Reference Victor2009; Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010).

‘Ideational influences’ concern both the room for manoeuvre for actors to influence decision-making and how actors perceive the world. Both kinds of ideational influence may involve the emerging norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform, which draws attention to the issue of fossil fuel subsidies and defines these subsidies as inappropriate (see Chapter 5). The two kinds of ideational influence may also concern the various definitions of fossil fuel subsidies; debates, for instance, can be shaped by the definition that is used to determine whether a country has subsidies (see Chapter 2). The former kind of ideational influence includes influences on the public and policymaking agendas. Reports, statements or commitments by the institutions affecting the placement of fossil fuel subsidies on the public (media) and policymaking (within government, parliamentary committees, etc.) agendas constitute the most relevant instances of influence. Such influence allows actors favouring reform to initiate a debate about whether the country has fossil fuel subsidies and whether they should be reformed. In this way, ideational influence may allow for new framings (e.g. framing a policy as a fossil fuel subsidy), legitimise goals (e.g. to reform fossil fuel subsidies) and associate non-compliance with them with reputational costs.

The ideational influences affecting actors’ perceptions involves policymakers internalising specific goals and beliefs (particularly regarding appropriateness) and taking them for granted (Checkel Reference Checkel2005: 804). It is relevant to focus on whether policymakers have internalised beliefs regarding fossil fuel subsidies, such as the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform or the more specific belief that a given kind of policy (such as tax exemptions) constitutes a fossil fuel subsidy. This chapter focuses on the institutions influencing policymakers directly, since this is the main channel of interaction between the international institutions and the domestic level.

‘Learning’ is understood as changing beliefs concerning the ‘best’ (generally most efficient or effective) way to achieve an objective based on experience, in this case that of other actors (Dobbin et al. Reference Dobbin, Simmons and And Garrett2007: 460). Unlike ideational influence, learning does not involve changes in actors’ goals or beliefs and ideational structures defining what is appropriate. Here it is pertinent to focus on international institutions actively disseminating best practices (see Lehtonen (Reference Lehtonen2007) regarding the OECD and Seabrooke (Reference Seabrooke2012) regarding the IMF) or acting as forums for peer-based learning (from both successful and unsuccessful reforms) among policymakers (Haas Reference Haas2000).

‘Power-based influences’ may affect the power of those opposed to, or conversely, in favour of fossil fuel subsidy reform. The institutions may alter the power of these actors by imposing direct conditionalities on the states (e.g. IMF or World Bank programmes) or by providing support (e.g. technical assistance) for reform. Such influences may hinder certain actions while empowering or disempowering particular constituencies (Kahler Reference Kahler2000). The power of international economic institutions is well documented, particularly the influence of IMF and World Bank structural adjustment programmes (Vreeland Reference Vreeland2007).

6.3 Methods

The countries studied in this chapter are Denmark, India, Indonesia, the United Kingdom and the United States. These countries have been selected based on their important roles in the international discussions of fossil fuel subsidy reform, yet they vary in terms of experiences with such reform. While the United Kingdom and Denmark have been reluctant to acknowledge that they provide fossil fuel subsidies, the other countries acknowledge their subsidies but have seen varying success on reform. Reform has been very limited in the United States and mixed in Indonesia (pre-2014), but successful reforms have taken place in India and Indonesia (post-2014). Interestingly, while the United Kingdom and Denmark have actively promoted fossil fuel subsidy reform at the international level, India has been outright sceptical of international efforts. Lastly, the countries studied cover both industrialised and emerging economies (but not least-developed countries due to those countries’ smaller share of global fossil fuel subsidies) and G20 members as well as non-G20 members. The focus is on the period following the 2009 G20 commitment on fossil fuel subsidy reform, after which fossil fuel subsidies became intrinsic to the activities of the international economic institutions.

Ideational influence on the public agenda has been operationalised by identifying articles in the two leading newspapers of each country that establish a connection between the international institutions’ activities regarding fossil fuel subsidies and the country in question. Such a connection could include using IMF or OECD estimates of a country’s fossil fuel subsidies when discussing reforming the policies included in those estimates. This number is compared to the total numbers of articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies domestically and internationally. The analysis also focuses on whether domestic actors (e.g. non-governmental organisations) were successful or, conversely, unsuccessful in exploiting the activities of the international institutions to promote subsidy reform.

Learning, power-based influence and ideational influence on the beliefs and goals of actors have been studied through process tracing, relying on a combination of official documents, key informant interviews, second-hand sources and the author’s observations as an official working on the topic. The official documents originate from the governments and institutions in question. The key informants (a total of 22) are primarily senior officials currently or previously responsible for fossil fuel subsidies at finance ministries or other key ministries or agencies in the countries studied, as well as in some cases representatives of the institutions that interact with the country. Since ideational and learning-based influences predominantly take place via direct interaction between officials and the institutions, the informants selected have been central to this interaction, which is why most of them come from finance ministries.

Ideational and learning-based influences on the beliefs and goals of actors can be identified in terms of whether the understandings and framings of key issues inherent to official documents change over time and whether informants point to such changes stemming from the institutions. Power-based influence is identified, first, by identifying whether the institutions had programmes in place that could influence the power of domestic fossil fuel subsidy actors within the country in question and, second, whether key informant interviews and secondary sources show that these programmes indeed influenced decision-making regarding fossil fuel subsidies.

The analysis also explores the degree to which the institutions were influential compared with other factors affecting whether and how countries would reform fossil fuel subsidies.

6.4 International Economic Institutions Addressing Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

The efforts of international economic institutions to address fossil fuel subsidies go back decades but were raised to a higher level by the 2009 G20 commitment to ‘phase out and rationalise over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support for the poorest’ (G20 2009). The commitment resulted in a process, among others, by which the member states report their fossil fuel subsidy reform strategies and timetables. In the reports, it is up to the members to identify which fossil fuel subsidies exist in their own country and how to phase them out. Seven countries (Australia, Brazil, France, Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and the United Kingdom) have claimed to have no inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, whereas other countries have submitted plans for phasing out their subsidies with varying degrees of ambition (Kirton et al. Reference Kirton, Larionova and Bracht2013: 62–69). In 2009, the G20 also asked the World Bank, the OECD, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries to analyse the scope of fossil fuel subsidies and to provide suggestions for implementing this initiative.

Later, the G20 added the possibility for states to submit their fossil fuel reform strategies to voluntary peer reviews by other G20 members and representatives of international organisations. At the time of writing, the United States and China had completed their peer reviews, while those of Germany and Mexico were in progress.

Crucial to the discussion of whether a country has fossil fuel subsidies is what definition of fossil fuel subsidies is used and the degree to which one focuses on consumption or production subsidies (van Asselt and Skovgaard Reference van Asselt, Skovgaard, Van de Graaf, Sovacool, Ghosh, Kern and Klare2016). Regarding definitions, analysts can use an ‘inventory’ or ‘conferred-benefits’ approach, which focuses on identifying government activities that transfer benefits to specific groups (e.g. consumers of kerosene), or a ‘price-gap’ approach, which focuses on whether prices are below a benchmark price, or a combination thereof (OECD 2010; see Chapter 2). The benchmark price is generally based on the international price of the fuel in question and sometimes also includes transport, distribution, value-added tax and taxes corresponding to the externalities stemming from the fuel (Gerasimchuk Reference Gerasimchuk2014). Regarding producer subsidies (directed at the extraction of fossil fuels) and consumer subsidies (directed at the use of fossil fuels), the latter are concentrated in developing countries, whereas the former are common in both industrialised and developing countries.

Beyond the G20, the OECD addressed fossil fuel subsidies before the G20 commitment as part of their environmental performance reviews of individual member states, studies of pricing policies and general studies. The OECD’s activities created knowledge about fossil fuel subsidies and promoted the norm that fossil fuel subsidies should be reformed (Skovgaard Reference Skovgaard2017). Using a total support estimate approach (fundamentally an inventory approach that also includes price-gap analysis) to identifying fossil fuel subsidies, the OECD Secretariat found fossil fuel ‘support’Footnote 1 measures in all 34 OECD countries (OECD 2010, 2011). Furthermore, the OECD Secretariat has arranged workshops on fossil fuel subsidies for representatives of its members.

The IMF and the World Bank have both followed a two-pronged approach: they induce states following adjustment programmes to reform their subsidies, and they provide knowledge about and promote fossil fuel subsidy reform. The first approach dates back decades, as the two institutions have promoted the restriction of any kind of subsidy irrespective of its environmental consequences. The second took off after the G20 commitment, especially following the G20’s request to the World Bank and other organisations to analyse fossil fuel subsidies. Importantly, in 2013 and 2015, the IMF published reports using a price-gap approach that included environmental externalities in the benchmark; this approach led to estimates of global fossil fuel subsidies of, respectively, USD 1.9 trillion and 5.3 trillion (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Coady and Fabrizio2013; Coady et al. Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and Shang2015). The IMF’s definition constituted a radical break with the established definitions within international institutions, and as a result of this definition, the IMF estimates are many times higher than the estimates of global subsidies by, for example, the IEA (USD 325 billion in 2015, based on benchmark prices without such externalities; IEA 2016).

6.5 Influencing Domestic Fossil Fuel Subsidies

6.5.1 United States

The OECD identifies US federal fossil fuel subsidies as tax expenditures in support of producers of oil, gas and coal and as consumption subsidies, particularly those directed at the energy costs of low-income households. Both are valued at greater than USD 1 billion (OECD 2016e). The IMF estimates that fossil fuel subsidies in the United States total USD 700 billion, of which non-priced externalities constitute more than USD 600 billion (IMF 2015). The US federal government has long acknowledged the existence of US fossil fuel production subsidies. Particularly in 2011 and 2012 – but also in budget proposals for other years – the Obama administration and Democratic senators attempted to end tax breaks for fossil fuel companies as part of budget-related negotiations. Yet these reforms did not pass the Senate due to opposition from Democrats from fossil-fuel producing states and Republicans (Rucker and Montgomery Reference Rucker and Montgomery2011; US Senate 2012). However, a liability cap and two royalty exemptions for oil and gas extraction – which amounted to tens of million dollars annually – were identified in the reports to the G20 as fossil fuel subsidies that could be reformed without congressional approval. They were terminated, respectively, in 2014 and in 2016 immediately following the presidential elections (US Government 2015; Bureau of Land Management 2016). Internationally, the United States has actively promoted fossil fuel subsidy reform, especially in securing the adoption of the G20 commitment (see Chapter 5). This active role complemented the Obama administration’s domestic effort to phase out federal tax breaks to fossil fuel producers (Interview 1). It was mainly the White House and the Treasury that addressed fossil fuel subsidies both domestically and internationally, the latter being the department most engaged on a day-to-day basis (Interview 2).

On the public agenda, fossil fuel subsidies have received more attention over the years (Table 6.1), but only within the domestic context about proposals to end tax breaks. As Table 6.1 shows, the total number of articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies increased with a peak of 22 in 2012. However, only a few of them referred both to fossil fuel subsidies (in a way that related to US subsidies) and to the international economic institutions, peaking with five articles in 2015. None of the articles made a connection between the activities of the international institutions and reforming domestic fossil fuel subsidy reform (e.g. by referring to the institutions’ reports when discussing fossil fuel producers’ tax breaks).

Table 6.1 Fossil fuel subsidy debate in the United States: New York Times and Washington Post coverage

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to US fossil fuel subsidies and international economic institutions | 3 (G20) | 1 (G20) | 1 (G8) | 2 (1 OECD, 1 World Bank) | 2 (World Bank) | 0 | 5 (2 OECD, 2 G20, 3 IMF, 1 World Bank) | 14 |

| All articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies (international and domestic) | 3 | 6 | 20 | 22 | 9 | 8 | 16 | 84 |

The US government submitted a self-report of the federal policies it considered fossil fuel subsidies, which was reviewed by a team chaired by the OECD Secretariat and including representatives from China, Germany and Mexico. In this report and in the 2014 G20 progress report, the United States acknowledged that both tax reductions and support for low-income households’ energy costs constitute fossil fuel subsidies but argued that the latter were not inefficient and hence should not be reformed (US Government 2014, 2015). The 2015 report included four tax exemptions and a liability cap (ranging from USD 0 to 342 million) that had not figured in the 2014 report (US Government 2014). These five subsidies were identified in an interagency process carried out in anticipation of the peer review with the intention of identifying additional subsidies that merited inclusion (Interview 3).

In this way, the G20 changed the policymaking agenda by placing the identification of fossil fuel subsidies on the agenda of several agencies that do not usually deal with the issue. It also changed the ideational context of action by reframing specific policies as fossil fuel subsidies and making it difficult to argue that they did not constitute such subsidies. The three subsidies reformed are among those acknowledged in the 2015 report, but not in the 2014 report (and were the only ones not requiring congressional approval); in this way, the Obama administration sought to live up to the G20 commitment to the greatest extent possible within the constraints of the political system. Yet the decision to terminate one subsidy – the liability cap – was made one year before the peer review, whereas the decision to terminate the royalty exemptions were already well under way during the review; the latter decision was adopted within the Department of the Interior in isolation from the policy processes addressing the G20 commitment (Interview 4). The peer review agreed with the US self-review regarding the subsidies identified (including support for low-income households’ energy costs not being inefficient), but it also argued that the support for inland waterway infrastructure mainly used to transport fossil fuels – not included in the self-report – constituted a fossil fuel subsidy (G20 Peer Review Team 2016: 31). It is noteworthy that the OECD chaired the peer review and hence exerted ideational influence over the United States due to the G20 commitment. Otherwise, the OECD’s definition of specific policies as subsidies – as included in its own reports – had little impact, since these policies had already been acknowledged as subsidies. Altogether, the G20 commitment institutionalised the norm of fossil fuel subsidy reform, which the Obama administration sought to adhere to within domestic constraints. The G20 commitment also held the United States accountable in regard to policies it was reluctant to define as fossil fuel subsidies.

In terms of learning, Treasury officials interacted with the IMF officials who developed the broader IMF definition of fossil fuel subsidies, which facilitated understanding of the issues in both organisations (Interview 5). Yet this collaboration did not induce the Treasury to adopt a price-gap approach that includes environmental externalities, in adherence with the IMF’s definition of fossil fuel subsidies (Clements et al. Reference Clements, Coady and Fabrizio2013).

Finally, the United States has not been subject to any conditionalities, support or other programmes from the international economic institutions that could alter the power of actors involved in decision-making regarding fossil fuel subsidies. Consequently, power-based influences (at least in the sense used here) did not play a role.

6.5.2 United Kingdom

The OECD identifies fossil fuel subsidies in the United Kingdom as consisting mainly of reduced rates of value-added tax for fuel and power and of the covering of liabilities related to coal mining. It estimates the value of these to be several billion pounds (OECD 2016d). The IMF estimates UK fossil fuel subsidies at GBP 40 billion, of which non-priced externalities constitute more than GBP 36 billion (IMF 2015). The UK government has promoted fossil fuel subsidy reform at the international level, including within the G20 (Interview 6). Internationally (in the reports to the G20) and domestically, the UK government has argued that the United Kingdom provides no inefficient fossil fuel subsidies (Kirton et al. Reference Kirton, Larionova and Bracht2013: 62–69). This argument is based on the definition of fossil fuel subsidies as ‘any Government measure or programme with the objective or direct consequence of reducing, below world-market prices, including all costs of transport, refining and distribution, the effective cost of fossil fuels paid by final consumers, or of reducing the costs or increasing the revenues of fossil-fuel producing companies’ (Department of Energy and Climate Change and HM Treasury 2013: para. 122).

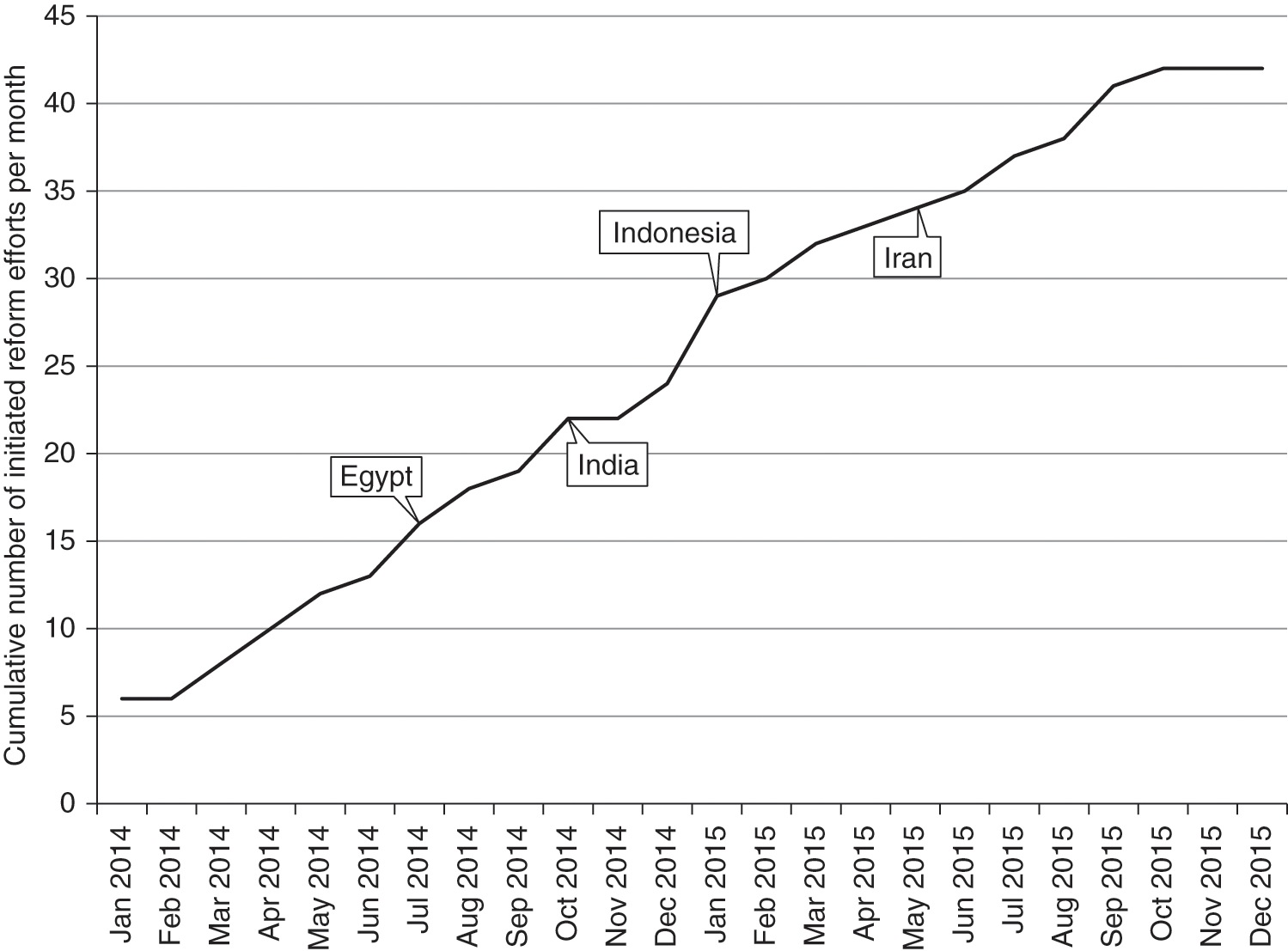

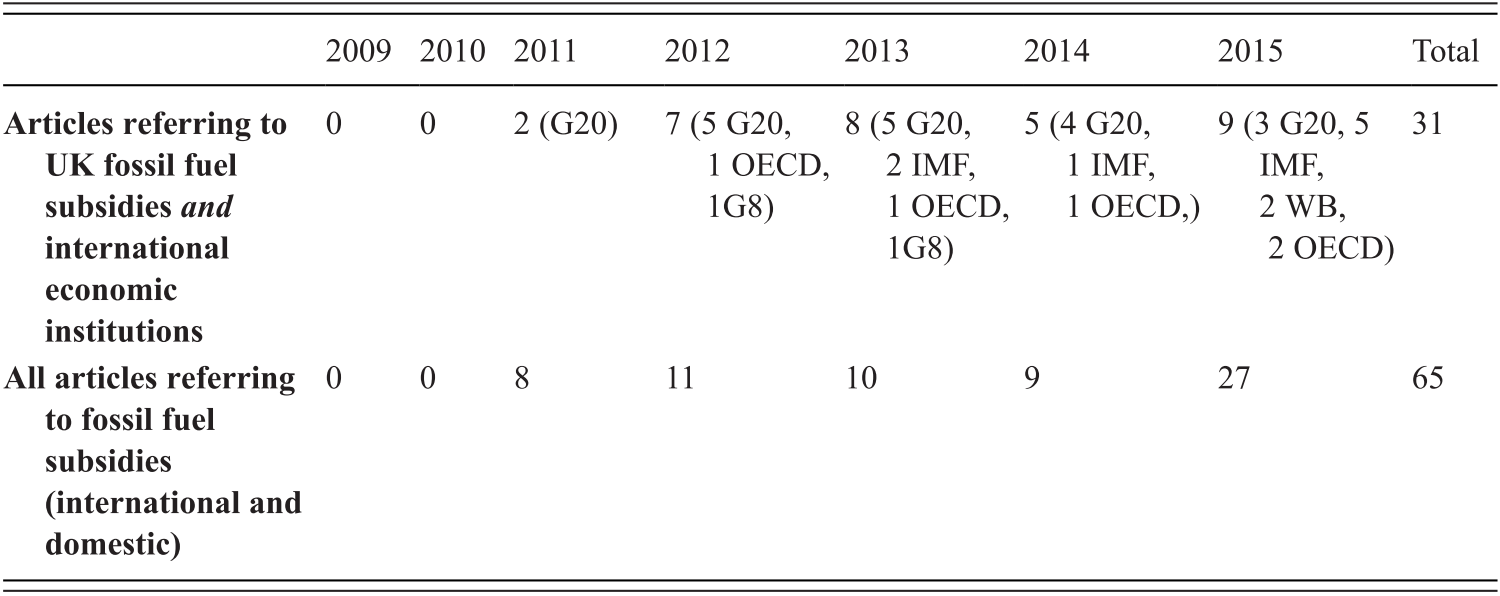

On the public agenda, the number of newspaper articles mentioning fossil fuel subsidies has increased substantially since 2011 (Table 6.2). Several articles link the G20 commitment and the IMF’s 2015 report to fossil fuel subsidies within the United Kingdom. Actors including members of the House of Commons’ Environmental Audit Committee pointed to the perceived inconsistency between the UK government’s high international profile on fossil fuel subsidy reform and the existence of, even growth in, fossil fuel subsidies domestically (Carrington Reference Carrington2015).

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to UK fossil fuel subsidies and international economic institutions | 0 | 0 | 2 (G20) | 7 (5 G20, 1 OECD, 1G8) | 8 (5 G20, 2 IMF,1 OECD, 1G8) | 5 (4 G20, 1 IMF, 1 OECD,) | 9 (3 G20, 5 IMF, 2 WB, 2 OECD) | 31 |

| All articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies (international and domestic) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 27 | 65 |

Importantly, the ideational influence from the G20 commitment put fossil fuel subsidies on the policymaking agenda when the House of Commons’ Environmental Audit Committee (which includes members of all major parties) issued a report on energy subsidies challenging the UK government’s claim that it does not subsidise fossil fuel (2013). The report opened new venues for actors – including environmental organisations and renewable-energy companies – opposed to fossil fuel subsidies. Many of these actors testified to the Committee, which relied on these testimonies in its report, particularly their criticism that the government’s fossil fuel subsidy definition was too restrictive (House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee 2013: 6–9). The Committee used a price-gap approach that (unlike the government) included value-added tax in the benchmark price and defined, for example, a consequently lower value-added tax on households’ and small businesses’ electricity bills as a GBP 3.6 billion subsidy. The Committee – unlike the UK government – also defined tax rebates for high-cost oil and gas fields and fracking as subsidies.

UK officials from the Treasury and other ministries interacted regularly with the different international economic institutions, as the Treasury was responsible for developing the UK government’s definition of fossil fuel subsidies and for the G20, the IMF and, to a lesser extent, the World Bank. The two other ministries with important roles – the Department of Energy and Climate Change and the Department for International Development – focused mainly on the international level (Interviews 7 and 8). This interaction increased awareness of the issue but did not amount to fundamental ideational and learning-based influences on Treasury beliefs and goals regarding British fossil fuel subsidies. This was mainly because even before the institutions became closely involved, the Treasury perceived fossil fuel subsidies in terms similar to those of the economic institutions, namely as undesirable, because of their macroeconomic effects and, as a secondary consideration, their environmental effects (Interview 6; see Stern (Reference Stern2006: 277–79) for an example of how the Treasury perceived fossil fuel subsidies through an environmental economics perspective). The Treasury interacted most closely with the IEA, which defines fossil fuel subsidies (using a price-gap approach excluding environmental externalities) in a way similar to how the UK government had already defined it (Stern Reference Stern2006: 277–79).

Finally, similarly to the United States, the United Kingdom has not been subject to any programmes from the international economic institutions that could alter the power of relevant actors, and hence power-based influences did not play a role concerning UK fossil fuel subsidies.

6.5.3 India

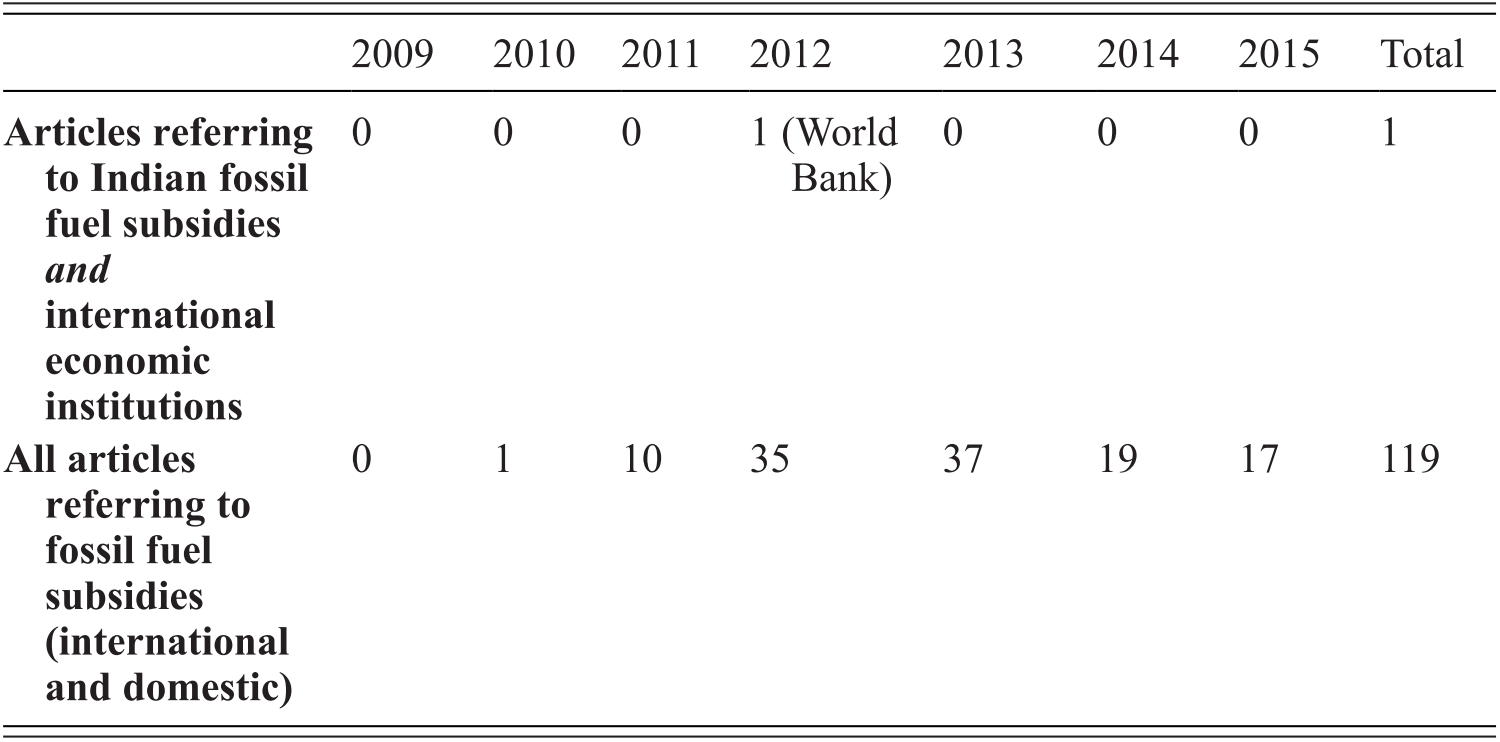

According to the OECD, fossil fuel subsidies in India consist almost exclusively of selling diesel, kerosene and liquefied petroleum gas at a loss and are estimated at hundreds of billions of Indian rupees or billions of US dollars (OECD 2016b). The IMF estimates Indian fossil fuel subsidies at USD 277 billion, of which non-taxed externalities constitute more than USD 250 billion (IMF 2015). The Indian government acknowledges the existence of Indian fossil fuel subsidies and has since 2013 carried out a series of reforms, liberalising prices and focusing subsidies on the poor (see Chapter 12).

The ideational influence of the institutions on the public agenda is extremely limited (Table 6.3). Only once did the two major newspapers refer to fossil fuel subsidies and one of the institutions (the World Bank) in the same article, although without explicitly linking them and instead focusing on the Rio+20 summit and the ‘green economy’ (Ganesh Reference Ganesh2012). Rather, fossil fuel subsidies were framed solely as a domestic issue on the public agenda, yet they increased in importance.

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to Indian fossil fuel subsidies and international economic institutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (World Bank) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| All articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies (international and domestic) | 0 | 1 | 10 | 35 | 37 | 19 | 17 | 119 |

This framing corresponds to the Indian government’s scepticism about addressing fossil fuel subsidy reform on the international level, including within the G20. Ideational influences have been limited by this scepticism, particularly regarding the G20 framing of fossil fuel subsides as an environmental issue, since the Indian government preferred to frame it as an economic and fiscal issue (see e.g. Dasgupta Reference Dasgupta2013). The scepticism reflects the historically predominant (yet increasingly challenged) view within the Indian elite that climate change is the responsibility of industrialised countries and that developing countries should not commit to climate change actions (Thaker and Leiserowitz Reference Thaker and Leiserowitz2014). Nonetheless, the Indian government has implicitly acknowledged the relevance of the norm to India by reporting its plans to reform fossil fuel subsidies to the G20.

The Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas are responsible for the reforms. According to the former and current officials of the two ministries interviewed, the main reasons for undertaking these reforms have been fiscal and macroeconomic: there are cheaper ways of alleviating poverty, and the fossil fuel subsidies were detrimental to the public budget and the balance of trade (as they increased oil imports). Two contextual factors made the reform possible: low oil prices and the liberalisation of the Indian economy since the early 1990s. Low oil prices created the scope in which to liberalise fuel prices without attracting public protests. Although the liberalisation of the Indian economy is arguably the result of ideational influences promoting the belief in free-market economic governance (Mukherji Reference Mukherji2013), more specific ideational influences concerning fossil fuel subsidies have not been significant.

Concerning learning, the World Bank arranged workshops that provided opportunities for peer-based learning from other emerging economies that had undertaken similar fossil fuel reforms and in this way influenced the shape of concrete fossil fuel subsidy reforms in India (Interview 9).

In the period after 2009, India has not been subject to any programmes from the international economic institutions that could alter the power of relevant actors, and hence power-based influences did not play a role concerning Indian fossil fuel subsidies during the period studied here.

6.5.4 Indonesia

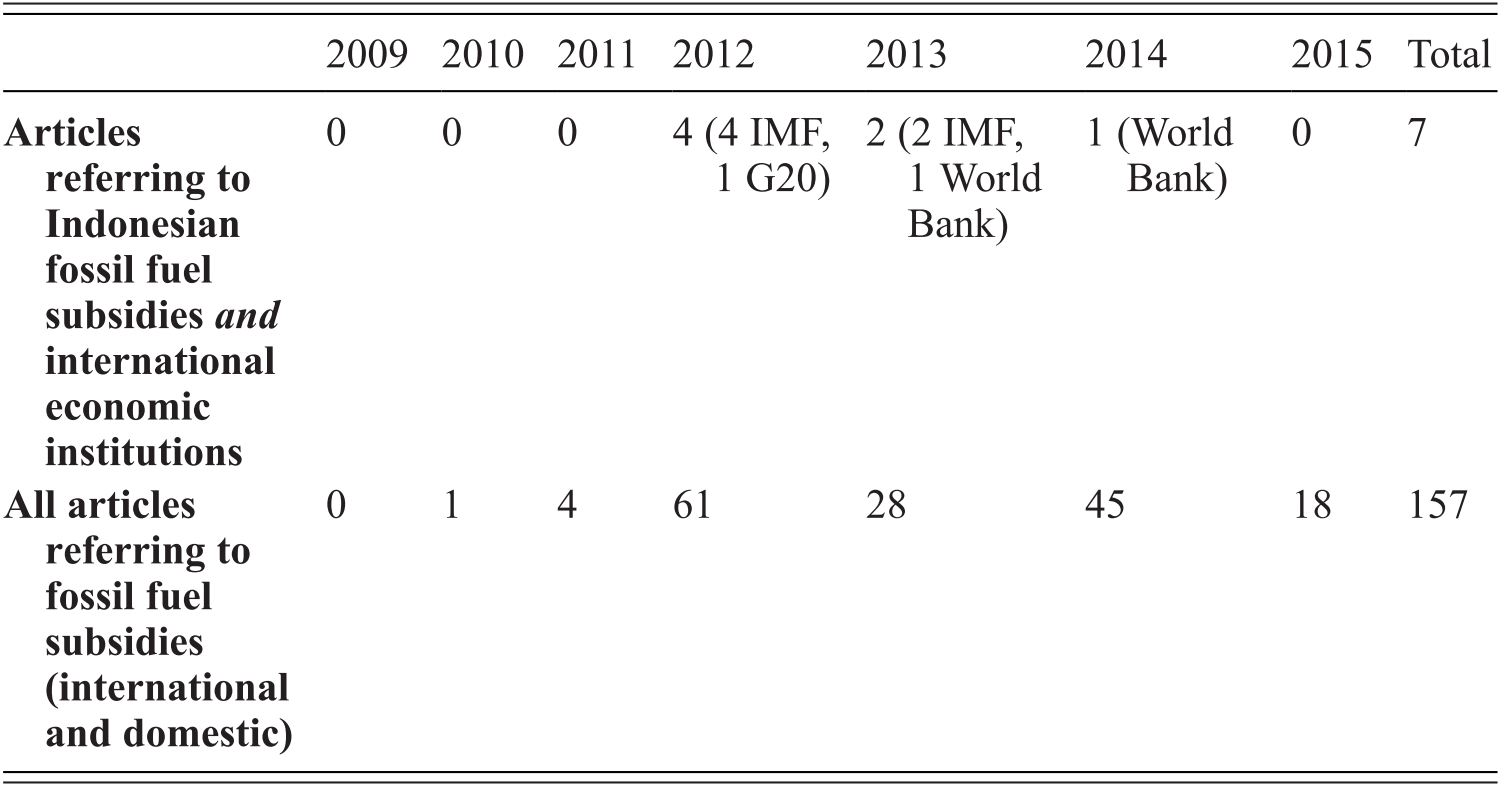

The OECD identifies fossil fuel subsidies in Indonesia as constituted mainly by the setting of oil product prices below the market price; it estimated this support as totalling more than IDR 100 trillion or USD 10 billion (OECD 2016c), which at times equals 4.5 per cent of gross domestic product or 20 per cent of public expenditure (Dartanto Reference Dartanto2013). The IMF estimated Indonesian fossil fuel subsidies at USD 70 billion, of which non-taxed externalities constitute more than USD 50 billion (IMF 2015). The Indonesian government acknowledges that these policies constitute fossil fuel subsidies and has since 2000 attempted, with varying success, to reform them (see Chapter 11). Since Joko Widodo became president in 2014, subsidies to petrol have been phased out and diesel subsidies reduced (IISD 2015).

The institutions’ ideational influence on the public agenda has been very limited (Table 6.4). Most newspaper articles focus on solely on domestic aspects of subsidy reform. The few articles that link these reforms to the institutions mainly rely on IMF reports – especially the 2013 report – to substantiate calls for fossil fuel subsidy reform. Generally, the Indonesian public are unaware of the existence of fossil fuel subsidies or tend to underestimate them (see also Chapter 11).

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to Indonesian fossil fuel subsidies and international economic institutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4 IMF, 1 G20) | 2 (2 IMF, 1 World Bank) | 1 (World Bank) | 0 | 7 |

| All articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies (international and domestic) | 0 | 1 | 4 | 61 | 28 | 45 | 18 | 157 |

Regarding ideational influences, Indonesia has continuously reported its plans and efforts to reform fossil fuel subsidies to the G20 and committed itself to undergo a peer review (Steenblik Reference Steenblik2016). The fossil fuel subsidy reform norm has been influential among government policymakers, since failure to live up to the commitment is considered politically embarrassing (Interview 10). World Bank interaction with policymakers and technical officials has been close and has covered all three kinds of influence; in addition, it has shaped the most recent round of fossil fuel subsidy reform when the Widodo presidency moved the issue up the policymaking agenda. First, ideational influence – in terms of co-producing and disseminating an analysis of fossil fuel subsidies – was important in influencing policymakers’ beliefs concerning these subsidies, particularly by framing the subsidies in terms of inequality (most are captured by the non-poor) and the other purposes (especially infrastructure) that the money could finance (Interview 11). The IMF and, to a lesser degree, the OECD have also been influential in providing analysis of Indonesian fossil fuel subsidies. The IMF collaborated with the World Bank, following a standard division of labour in which the IMF focused more on the monetary exchange rate and broad fiscal setting, whereas the World Bank focused on sectoral and microeconomic issues (Interview 12). While civil servants (at least during the period studied) considered fossil fuel subsidies problematic and hence could not be influenced in this direction, an analysis of how to undertake fossil fuel subsidy reform could influence them to a greater degree (Interview 13). The institutions also could influence the policymaking agenda by framing the subsidies in terms of inequality and the possibilities for using the money for other purposes (Diop Reference Diop2014). Second, regarding learning, the World Bank facilitated important learning about the experiences of other countries replacing fossil fuel subsidies with targeted measures – such as direct cash transfer to the poor – by inviting officials from Indonesia’s planning ministry Bappenas to Brazil to learn from their cash-transfer scheme (Interview 11). This influence shaped the compensatory measures that experts argue are crucial to the successful reform of fossil fuel subsidies (Beaton and Lontoh Reference Beaton and Lontoh2010; OECD 2011).

Finally, power-based influence can be discerned, since the World Bank provided the technical assistance necessary for creating the cash-transfer scheme (Interview 11), thus making certain policies possible by altering the resources available. According to Chelminski (Chapter 11), the provision of social assistance constituted the most important factor and a necessary condition for the success of the recent reforms; thus, without this power-based influenced from the World Bank, it is far from certain that the reforms would have succeeded. In 2002, and thus before the period mainly studied here, the IMF programme following the 1997 Asian financial crisis led to increases in fixed fuel prices (Government of Indonesia 2002; see also Chapter 11). After this programme ended, the absence of direct leverage meant that the IMF played the part of a trusted policymaker rather than an active stakeholder (Interview 12).

However, the drivers underlying Indonesian fossil fuel subsidy reforms are primarily domestic. The Indonesian Ministry of Finance has been an important driver of such reforms (and interacted closely with the World Bank) due to concerns about the impact of reforms on the budget (Interview 14).

6.5.5 Denmark

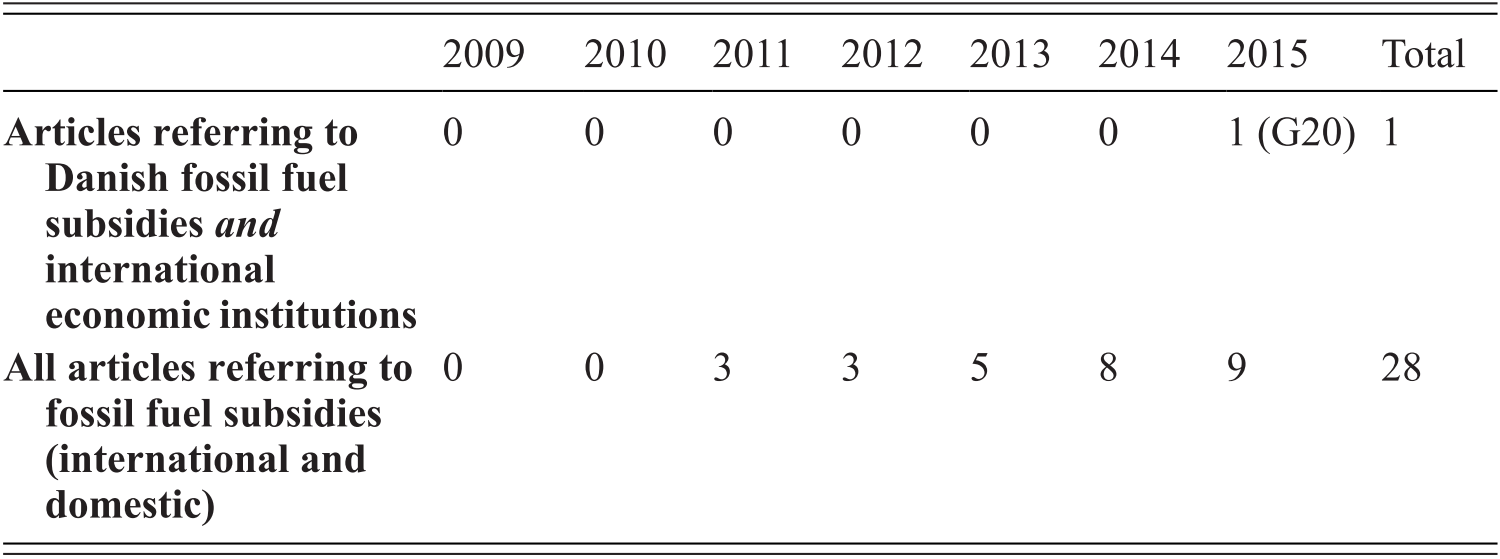

According to the OECD, the Danish government subsidises fossil fuels by reducing energy taxes for fuels used for specific purposes and for oil extraction. The subsidies, as identified by the OECD, are estimated to amount to billions of Danish kronor or hundreds of millions of US dollars (OECD 2016a). According to the IMF, fossil fuel subsidies in Denmark amount to USD 5.8 billion, of which non-taxed externalities constitute more than USD 4 billion (IMF 2015). The Danish government has acknowledged that fossil fuel production is subsidised but argues that tax expenditures for consumption do not constitute subsidies because total fossil fuel taxes exceed the total externalities (Danish Ministry of Climate Change 2015). Internationally, the Danish government has promoted fossil fuel subsidy reform, particularly through the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (see Chapter 9).

The ideational influence on the public agenda is limited (Table 6.5). Despite the increasing focus on fossil fuel subsidies since 2010, only one article linked one of the institutions (the G20, of which Denmark is not a member) and Danish fossil fuel subsidies (Nielsen and Andersen Reference Nielsen and Andersen2015). Generally, fossil fuel subsidies have been framed as an international rather than a Danish phenomenon.

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to Danish fossil fuel subsidies and international economic institutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (G20) | 1 |

| All articles referring to fossil fuel subsidies (international and domestic) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 28 |