The dead. The body count. We don’t like to admit the war was even partly our fault because so many of our people died. And all the mournings veiled the truth. It’s not “lest we forget,” it’s “lest we remember.” That’s what all this is about – the memorials, the cenotaph, the two minutes’ silence. Because there is no better way of forgetting something than by commemorating it.

A tour of massacre sites has become an obligatory part of any business or tourist visit to post-genocide Rwanda. Both deeply affecting and also disconcerting, the genocide-site pilgrimage highlights the horrors of the genocide while at the same time revealing the crass uses for which the memory of the genocide is employed. Most genocide tours begin at the impressive Kigali Memorial Centre at Gisozi on the outskirts of the capital city. The genocide museum is a striking white stucco modernist structure perched atop a hill near the location of a major roadblock in 1994 where hundreds of Tutsi were slaughtered. It was built with foreign funds, using the latest in museum design, and informed by Holocaust museums in the United States, Europe, and Israel. The first portion of the museum traces the history of the genocide, in English, French, and Kinyarwanda, from pre-colonial times until 1994. There are sections on politics, propaganda, women, and other themes, in a presentation reminiscent of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. The historical narrative is accompanied by a few primary documents, like the Bahutu Manifesto and photos, with appropriate interpretive commentary.

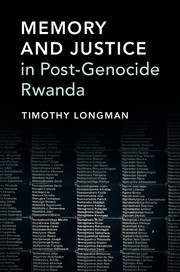

The rest of the museum uses less straightforward means to create an impression of the genocide that appeals more to the emotions than to the mind. One room is filled with abstract statues depicting the suffering of the genocide. Another room focuses on the children killed. Still another room contains photographs of people who died in the genocide, hung as if floating in space on wires that run from floor to ceiling. This image from the museum has become iconic, gracing the covers of books and appearing in discussions of genocide or violence. The museum is surrounded by a memorial garden providing beautiful views of Kigali. A wall of names lists all of the people from Kigali known to have been killed in the genocide, reminiscent of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. Finally, there is a mass grave, large slabs of concrete that line the side of the garden with the best views, and on one side an open mausoleum, where families who were able to identify the remains of their loved ones have placed the bodies in coffins, draped in purple cloth and white lace, and stacked one on the other in crowded underground rooms, accessible by concrete stairs. (See Figure 1.) The museum documentation claims that over 250,000 “victims of the genocide” killed in Kigali are buried in the mass grave. The memorial center is both informative and evocative, an effective introduction to the genocide – or at least the government’s narrative of it – for those with little knowledge, not only stirring emotions but also providing careful direction as to how one should think about the events that led up to 1994.

Figure 1 Coffins exposed at the Kigali Memorial Centre

After the museum, the genocide tour generally continues to one of the memorialized massacre sites, most often one or both of the churches relatively easily accessed just south of Kigali in Bugesera, a region where the government resettled many Tutsi after violence in the 1960s and 1973. In April 1994 Tutsi fearing violence in Bugesera fled to the Catholic centers of Nyamata and Ntarama, and as in churches throughout the country, thousands were killed in the parish complexes. But, in contrast to much of the country, in Bugesera the death squads fled before they had disposed of the dead as the RPF rapidly advanced on the area. The bodies were left lying where they had fallen, a gruesome spectacle for the RPF troops to discover and strong evidence for them of the purpose of their armed intervention. After taking power, the RPF-led government retained control of the Nyamata and Ntarama churches, and for several years the bodies were left in place, sprinkled with powdered lime to stop them from rotting but otherwise left as testament to the horrors of the genocide. Unlike Murambi in Gikongoro, where the bodies were carefully laid out and displayed, at Nyamata and Ntarama the corpses were left in place – withered bodies with scraps of clothing still attached, mere skeletons, or in some cases scraps of bones – an arm, a leg. These sites were shocking, appalling, but also deeply offensive to the survivors who were not allowed to give their family members proper burials but rather had to leave them on public display.

In 2000, apparently bowing to pressure from survivors, the local communities, and the Catholic Church, the government allowed the bodies to be removed and the sites to be cleaned up. At Nyamata, a small center of commerce and education, the local Catholic community was forced to build a new church building just up the road so that the church where the massacres had taken place could remain a memorial. The churchyard at Nyamata is enclosed in a fence, and visitors must wait for a guide to come lead them on a tour. As at all the massacre sites, the guides at Nyamata are survivors of the massacres who tell their stories as they lead visitors through the building. The sanctuary has been decorated with reminders of the genocide. When I visited in 2002, the sanctuary was mostly bare, but the pews and part of the floor were later covered with piles of soiled clothes from genocide victims, creating a much more haunting and moving image. The altar cloth, a white cotton covering carefully decorated with cross-stitched flowers, had large blotches of brown that the guide explains are stains of the blood of those slaughtered here. On the walls too there were dark stains that the guide pointed out as remnants of blood, and the tin roof was riddled with holes, apparently caused by shrapnel from grenades. The basement crypt in the back of the church was lined with ceramic tiles, and there were several glass cabinets where skulls and other bones of victims were displayed. “There are plans to build a museum here,” the guide told me when I visited in 2002, but the museum has never been built.

The most affecting genocide memorial at Nyamata lay in the churchyard, which had been given over almost entirely to mass graves. Acceding to demands from survivors, the government agreed to clear the bodies from the church, but they did not allow a traditional burial. Under the supervision of the survivors’ group Ibuka, the bodies were placed in open mausoleums that were a compromise between the survivors’ desire to give their relatives a decent burial and the government’s desire to use the bodies of victims to demonstrate the horrors of the genocide. Unlike the Kigali center, where only caskets were exposed to public view, at Nyamata the corpses and skeletons were placed underground on tiered platforms, reminiscent of the catacombs of ancient Rome, and they are visible from above ground through large entryways. The top tier was filled with caskets containing the remains of those whose bodies were identified by their families. Should visitors wish to enter the crypts, stairs lead down inside, and there were neat passageways along the rows of corpses.

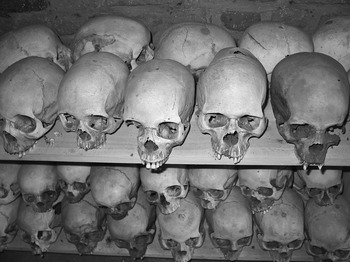

Less than ten miles away, the chapel at Ntarama was much smaller than Nyamata, not a full parish but merely a rural outpost for weekly prayer services or occasional Eucharist for those living too far from the central parish to attend mass on a regular basis. In 1994, some 5,000 people were killed at Ntarama. Like Nyamata, the chapel of Ntarama was initially left as it was found, with bodies grotesquely scattered around the building and grounds. Around 2001, the bodies were cleared from the church, but improvements had not yet been undertaken to create of Ntarama a sleek memorial like Nyamata or Gisovu. As a result, Ntarama was much more disturbing. When I first visited the church in 2002, several burlap bags in the back of the sanctuary were filled with bones. The guide, a rural Tutsi farmer who lived just down the road from the church, said that the bones were awaiting burial but that there were no funds available for a proper mass grave. The floor of the chapel was cluttered with the detritus of the people who had sought refuge in the place but instead found death – scraps of clothing, notebooks, and bones, some identifiable as ribs and finger-bones, others mere broken fragments. (See Figure 2.) It was still impossible to walk through the building without stepping on bones, creating a horrifying crunch under foot. At the front of the church, a cross was propped against the altar, where a solitary skull had been placed, creating a haunting monument. Just outside the entrance to the chapel, a shed held hundreds of skulls placed on display on a long platform. (See Figure 3.) In the buildings behind the chapel,there were piles of rotting clothes taken off the skeletons, and another pile of personal items – baskets, plastic basins, jerricans, and suitcases.

Figure 2 Skulls on display at Ntarama memorial site

Figure 3 The debris-strewn floor of Ntarama memorial site

Returning to Ntarama in 2005 with a group of colleagues, I found that the skulls had been moved into the chapel itself, displayed on open bookshelves in the back of the sanctuary, but few other changes had taken place. The piles of personal effects remained in the back buildings, and the floor of the chapel remained scattered with bones and other fragments of life. “Have the bones been buried?” I asked the guide, the same farmer I had met a few years before. “No,” he told me. “There is no money for that.” Since then, some improvements were made to the site. A large open metal shed was built over the chapel to protect the structure. The bones were taken out of the sacks, but rather than being buried, they were scattered around the floor of the church once again. Visitors had to step from bench to bench to avoid stepping on the remains. More bones were placed on the floor of a room behind the chapel, where the stained clothes of genocide victims were hung from the ceiling. The effect was disturbing and macabre, and the fact that the bones had been carefully placed on display was not obvious.

Driving back to Kigali, the genocide tour stops at a site just after the southern entrance to the city. There are several large mass graves here for people killed at a nearby school and at a roadblock that was situated on the road here. There is also a brick and cement monument to members of the human rights group Kanyarwanda killed in the genocide. Most moving, however, is a field filled with simple white crosses made of painted wood. This was an art installation, part of a consortium of African writers and artists brought to Rwanda in 1998 for three months to learn about the Rwandan genocide and produce works inspired by it. After several years, the white paint had faded and some of the crosses had tipped to the side or lost an arm, but this apparent disarray added to the effect of sadness and loss.

Of all these sites, Ntarama was undoubtedly the most affecting, because its unpolished rawness gave a sense of proximity to the genocide. The Genocide Memorial Center in Kigali was modern and sophisticated and very moving, but it also left one feeling a bit manipulated, rather like the reaction to Hollywood movies where events are orchestrated carefully to force tears but where the pathos does not ultimately seem genuine. Given the very true horror of the genocide, the sense of emotional manipulation is all the more disturbing. Perhaps it is the carefully worded script that lays out a single interpretation of the past that irritates, or the very polish that somehow seems to obscure a genocide that was in many ways low tech. And yet Ntarama, with its skulls on display and bone-strewn floor, is no less manipulative. It is merely that the lack of polish seems more visceral and therefore closer to the truth. There is no obvious transcript at Ntarama, and the hand of the government in creating an image of the genocide is less obvious.

At Ntarama, as at Nyamata and Murambi, visitors were asked to sign a guest book, where they could list their names and home countries and write reactions to the memorial – “Very sad.” “Never again” – and where their donations to the guide of one or two thousand francs were dutifully recorded. On my 2005 visit to Nyamata, I leafed through the book and noted the names of the visitors – mostly Europeans and Americans. The last visitors before me were United States officials – Pierre Prosper, the Special Ambassador for War Crimes, and Jendayi Frazier, the Undersecretary of State for Africa. These were the ultimate audience for these sites, it struck me.

Understanding Memorials and Memory

As the academic world has taken up the topic of memory, commemorations and memorials have become a major focus of scholarly analysis. In his comprehensive analysis of the “sites of memory” used to construct French Republican identity, Nora argued that in the past, people lived in close relationship with memory, in “milieux de memoire,” but that in the modern world, cut off as we are from family and places of origin and traditional values, we depend on “sites of memory” to construct a historical transcript of the past that serves to create a collective memory and, thereby, a shared national identity.Footnote 1 Coming at a time when scholars were exploring the constructed nature of identities, particularly national identities,Footnote 2 Nora’s work inspired many to analyze sites of memory in other contexts. Statues of prominent figures, war memorials, museums, and public holidays have all come under scrutiny for the narrative they seek to convey. As Jan-Werner Müller said, “Wherever ‘national identity’ seems to be in question, memory comes to be a key to national recovery through reconfiguring the past.”Footnote 3

Some scholars have taken issue with Nora’s suggestion that memorials and other sites of memory create a shared transcript and instead emphasize the contestation that surrounds sites of memory. James Young’s influential analysis of Holocaust memorials, for example, argued that they create “collected memories” rather than “collective memories,” since the same space can be interpreted and experienced in vastly different ways, providing a source of pride for one, and a mark of shame for another.Footnote 4 In societies where debate is possible, the creation of a memorial or a museum can become a focus for public debate about the past, as conflicting constituencies have divergent ideas that they hope to convey through a commemorative site. The erection of the Vietnam Veterans memorial in Washington, DC, in 1982, for example, inspired a debate over the legacies of the Vietnam War.Footnote 5 The Smithsonian’s planned 1995 exhibit of the Enola Gay, the airplane that dropped the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, brought to the surface controversies over the American role in the Second World War and the appropriateness of the use of nuclear weapons.Footnote 6 A memorial to victims of Peru’s political violence provoked conversations over who has the right to be considered a victim and who is labeled a perpetrator.Footnote 7 In a comparative analysis, Turnbridge and Ashworth found conflicting ways in which the past was managed in different societies, often being used to exonerate perpetrators, even by blaming victims. Yet they also recognized the possibility for commemorations to provide opportunities for reconciliation between perpetrators and victims.Footnote 8 These analyses suggest that memorials allow multiple interpretations and can be important vehicles for encouraging conversation about traumatic experiences of the past – but this assumes a context where open conversation is possible.

Many other scholars focus on the coercive nature of memorialization, looking at how political leaders and other elites dominate the presentation of the past and seek to manufacture politically useful collective memories. In his comprehensive argument for the importance of memory, Paul Riceour identified a number of “abuses of memory” related to commemoration and memorialization. He saw a danger in mere memorization taking the place of real historical memory, creating an “unnatural memory.”Footnote 9 He decried the manipulation of memory, in which, “The heart of the problem is the mobilization of memory in the service of the quest, the appeal, the demand for identity,”Footnote 10 and warned against forcing people to remember the past, which leads to its distortion.Footnote 11 Forest and Johnson found that in Moscow after the fall of communism, political elites sought to reinterpret Soviet-era monuments in their efforts to build symbolic capital. Their research on popular reactions to the memorials found that elites were responsive to popular sentiment but that in critical periods where symbols are open for reinterpretation, “powerful political actors … impress their conceptions of the national character onto the public landscape.”Footnote 12 In a study quite relevant for the analysis of memorials in Rwanda, Claudia Koonz compared memorialization and amnesia in East and West Germany following the Second World War. She asserted that “imposed official history … bears little resemblance to what people remember,” resulting in an “organized oblivion” that “vindicates leaders and vilifies enemies,” leaving “average citizens cynical and alienated.”Footnote 13 After the fall of the Berlin wall, East German museums went under renovation, seeking to integrate the Jews into the history of the concentration camps. Jews remained nevertheless unrecognized in popular memory, illustrating a disconnect between official attempts at consensus and popular sentiment.Footnote 14

Some scholars have analyzed the lacunae in official memorialization, the issues and events that are left out of memorials, that are – sometimes quite intentionally – excluded from the official historical narrative. Henry Roussou, for example, analyzed how in the aftermath of the Second World War, the French sought to exonerate themselves by emphasizing the heroism of the resistance while ignoring the collaboration of the Vichy regime and the fact that more people were involved in the Vichy regime than in the resistance.Footnote 15 Anne Pitcher argued that in Mozambique, even as the government’s official narrative sought to erase memory of past Marxist-Leninist policies, a process she called “organized forgetting,” urban workers kept alive this memory as a basis for making demands for rights.Footnote 16 The experiences of women have often been excluded from sites of memory. In particular, sexual violence against women is often a taboo subject and is sublimated in favor of narratives that highlight the heroics of men.Footnote 17

The growing literature on the connections between official commemoration and collective memory raises a number of questions to consider in relation to the commemorations of the Rwandan genocide. In this chapter, I review the various sites of memory in Rwanda – massacre sites, museums, holidays, and other official commemorations established by the Rwandan government. I contend that the government used memorialization to promote the historical narrative described in the previous chapter as collective memory. I argue that the government also used what I term Rwanda’s “sites of forgetting,” pointedly excluding from public commemoration particular events, people, and experiences that it hopes the population will forget or disavow. This review of the government’s agenda lays the groundwork for my consideration in Chapter 7 of how the Rwandan population itself interprets the past.

Manufacturing Memory: Genocide Memorials and Commemorations

In the years immediately after 1994, the scars of war remained visible throughout the Rwandan countryside. Bodies lay unburied in some genocide massacre sites, and in many places, hard rains washed away soils and exposed bodies tossed carelessly in shallow graves either during the genocide or in the violence that surrounded the RPF’s accession to power. Primarily local governments took up the task of organizing the cleanup of genocide sites, burying bodies left exposed, and exhuming and reburying bodies unceremoniously dumped in latrines and hastily dug shallow tombs. Marked mass graves quickly became ubiquitous on the Rwandan landscape, many of them slabs of cement with flowers planted around, others merely covered in earth, with a stone marker or small garden. Reburials were usually accompanied by a solemn service that included both religious prayers and statements by government officials.

Many other reminders of the genocide could be seen throughout the country. Much of Rwanda’s infrastructure was destroyed by the war – bridges, water systems, power lines, roads. With substantial support from the international community, the government set about rebuilding. The remains of many demolished homes were more poignant reminders of the genocide. Those who carried out the genocide sought not merely to kill the country’s Tutsi minority but to eradicate their very memory, so they symbolically demolished Tutsi homes, distributing as looted goods the roof tiles and windows and doors as well as household items like furniture and cooking pots. In at least a few cases, the RPF itself sought to match the symbolic attempt to eradicate the Tutsi by demolishing the homes or businesses of genocide leaders.Footnote 18 Post-1994 Rwanda was thus scattered with the carcasses of buildings, crumbling mud walls with weeds and brush growing in what had once been family homes and businesses.

Buildings also bore reminders of the war and genocide in other ways. The walls of homes and businesses in many of Rwanda’s cities were pocked by bullet holes and windows smashed or cracked. Most dramatically, the Parliament building perched atop a high hill in the administrative area of Kigali bore huge craters from bombs. The Parliament served as RPF headquarters during the failed transition begun under the Arusha Accords, and in April 1994 five hundred RPF troops fought their way out of the building to join the main force of RPF soldiers who advanced from the north as the FAR rained bombs on their encampment. Even as most buildings in Rwanda were repaired or torn down to make way for the massive building boom that swept the capital, and even as much of the Parliament building itself was refurbished, the tall office tower was left for years with its great bombed-out holes as a testament to the heroism of the grossly outnumbered RPF troops.

At the same time that the RPF oversaw the rebuilding of the country – the rehabilitation of the infrastructure, the return of people to their homes – they also sought to preserve at least some symbols of the events of 1994. The government established an Office of Memorials in the Ministry of Youth, Sports, and Culture to monitor the process of genocide memorialization. The government initially attempted to retain control of most of the dozens of churches that served as massacre sites, but under objections from church leaders, they relented, ultimately focusing on only a few church buildings geographically distributed throughout the country. In most cases, the bodies of victims had been removed and the churches repaired and scrubbed clean long before the arrival of the RPF in July, since the massacres occurred primarily in April. In the handful of cases where the RPF nonetheless sought to convert the churches into memorial spaces, some compromise was reached. The sanctuary in Kibeho was reconfigured and a portion walled off to create a memorial chamber. After a protracted struggle, the Catholic cathedral at Kibuye was returned to the church, but a large mass grave, memorial garden, and cenotaph were placed in front of the entrance. Nyamata was ultimately the only parish church not resacralized and returned to religious purposes, along with the chapel at Ntarama and the convent of Nyarabuye.

A late addition to the pantheon of memorials was a lonely hill high above the shores of Lake Kivu in the province of Kibuye. While most massacres took place in churches or other public buildings, survivors of the initial massacres in some communities fled to forested hillsides, where they hoped to hide.Footnote 19 Bisesero was an open hillside where the Tutsi of Kibuye Prefecture made a valiant last stand against their attackers. The Tutsi, most of whom had fled from massacres at places both nearby, like the Kibuye Stadium and Catholic cathedral, as well as further afield, such as Kibeho, gathered at this site because of its isolation and strategic position. Some 40,000 Tutsi are estimated to have taken shelter in the thick brush on this steep hill, and for six weeks, they successfully fought off the civilian militia with stones and rough-hewn spears and other improvised weapons. They organized themselves into a defense force and stood their ground against the better-armed militia groups. Yet with virtually all the other major massacres in Rwanda already complete, the militia, joined by soldiers and police, mounted a major assault on May 13 in which thousands were killed, but several thousand survived in hiding. Under repeated subsequent attacks, however, the numbers of Tutsi here were relentlessly whittled away until French soldiers arrived in late June 1994 as part of Operation Turquoise. When they arrived, the French found only about 1,000 survivors, bedraggled and starving, who emerged gradually from the bush, believing that the French had come to save them. In fact, after visiting the site, the French left, and the killing continued for several more days until the French sent another contingent to protect the few survivors.Footnote 20

The government raised up Bisesero as a symbol both of Tutsi resistance and also the incompetence and complicity of the international community. An official biography of Kagame discusses Bisesero in a typical fashion, “One major exception to the pattern of defenselessness and desperation stands out in the annals of the grisly period of the genocide ... The resistance put up by thousands of mostly unarmed Tutsi at Bisesero in Kibuye Province in the west of Rwanda constitutes a memorial in itself to the determination of one major group of the population to not become victims.”Footnote 21 While at the conclusion of the genocide corpses lay scattered across the hillside at Bisesero, shortly after the RPF victory, the bodies were buried in mass graves, and bodies of genocide victims from throughout the local area were brought to this location for interment. Around 2001, the government constructed a monument at Bisesero and renamed the site “The Hill of Resistance.” The monument consists of a path that mounts the hill with nine buildings representing the nine communes of Kibuye Prefecture at the time of the genocide. Each building contains bones said to be those of victims from each commune, though as in other sites, the exact source of these bones is unclear, since those killed at the site were buried a number of years before. As a website explaining the memorial stated, “These images of human remains … are a powerful reminder of the concept of ‘Never Again.’”Footnote 22

In addition to the major genocide memorials, the central government encouraged local governments to develop their own memorials. The annual commemoration of the genocide in April became a popular time to rebury remains of genocide victims and dedicate mass graves as memorials. The sheer number of mass graves, however, challenged the ability of governments with limited resources to develop and maintain memorial sites. While some sites were developed with attractive gardens, statues, and other features, many mass graves were little more than a large cement slab. At the time of our research, other mass graves were merely marked with crosses, though the government was working to gather bodies from these dispersed sites and rebury them in central memorials. In Kigali, for example, bodies had been brought from throughout the municipality to be buried at the Genocide Museum at Gisozi.

The construction of memorials was not the only means Rwanda used to commemorate the genocide. A year after the onset of the genocide, the government organized a Week of Mourning that has since become a major annual holiday for Rwanda. The first week of remembrance was scheduled from April 7 through April 14, with a national commemoration taking place on April 7 in Kigali, where a formal burial of the moderate Hutu Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana took place as well as the reburial of about 200 Tutsi killed at the Kigali Hospital. Local communities throughout the country also organized their own commemorations at massacre sites, many of them taking the opportunity to dedicate mass graves. In the years since, the government has declared a Week of Mourning annually, with a national ceremony of commemoration taking place at a different massacre site each year and many local communities organizing their own ceremonies of commemoration. The activities during the week are overseen by both the Office of Memorials and the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission, which organizes seminars and educational workshops. The commemoration ceremonies are accompanied by political speeches in which leaders such as President Kagame expound on the ongoing significance of the genocide and the need to remain vigilant lest genocide against Tutsi recur in Rwanda. Several times Kagame used the occasion of the annual commemoration to launch a harsh attack on those he claims promote a “genocidal ideology” that threatens the stability of Rwanda.Footnote 23 While the first annual commemoration included a focus on moderate Hutus who were also killed in the genocide,Footnote 24 subsequent commemorations focused increasingly on Tutsi victims and the heroism of the RPF in bringing the genocide to an end. These commemorations were an opportunity to reiterate the lessons that the government hopes the population takes from the memorials and the historical events that they memorialize. An address by President Kagame at the commemoration of the eighth anniversary of the genocide in 2002 held at the Catholic seminary at Nyakibanda in southern Rwanda gives a good idea of the sort of political messages pronounced at these events. Kagame explained that in 1994, even churches were not sanctuaries for those fleeing the violence:

This is what made the 1994 atrocities different from the horrors of the past, but there were also similarities. The similarities are that all those things that we are in the process of doing, for example the dignified burial of the dead, speaking about the massacres that took place, but also in trying to distinguish them by their size or people choosing to call them by another name, and this makes people want to forget the roots of the killings. All this finds its origins in bad politics and bad governance …

A professor of history has written about Africans, because of the many African problems, saying that Africans who studied or read history in books, read it only to pass their exams. They did not read history to learn something from it. It is useful to read history to understand something that can change life and leave behind the bad in moving toward the good … There are Rwandans who have read history without learning anything from it. If you look at the present, the astonishing thing … is that there are Rwandans who try to tell us their predictions that in five years, in ten years, it will not be surprising if there is again a genocide, and saying this in a manner that they think is political! These people who say this were the authorities. They stand here and speak about extraordinary things. These people, I ask myself what history they have read? … They say these things, but they say it is just politics! But it is politics that sows division among Rwandans. And after this they run to the embassies saying that they were just engaging in politics, and these embassies welcome them, these people who consider themselves very intelligent. They share tea saying that they are just engaging in politics. But this is the politics that kills people like the people who are dead here. It is not just machetes that killed; they were merely carrying out the program. People were killed first by politics.Footnote 25

The message of this and other commemorations is clear: without the leadership of the RPF, Rwanda would once again experience genocide.

In addition to the Week of Mourning, the RPF government decreed several other holidays related to the genocide. Liberation Day on July 4 celebrates the day that the RPF took control of Kigali in 1994. Although the genocidal government had fled Kigali weeks before and fighting continued for two more weeks before the FAR were routed from the country, the capture of Kigali after a three-month battle symbolically represented the effective seizure of power. Even as the Week of Mourning commemorates the beginning of the genocide, Liberation Day celebrates the end of the genocide and clearly links this to the RPF victory. The Day of Heroes held in February recognizes Rwandan heroes, mostly Hutu killed resisting the genocide or other instances of anti-Tutsi ethnic violence, such as Prime Minister Uwilingiyimana.

The Kigali Memorial Centre

In 2004, on the tenth anniversary of the genocide, the annual national ceremony of commemoration took place in conjunction with the dedication of the new Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, which has since become an important tool for conveying interpretations of the 1994 violence. (See Figure 4.) The center was built in cooperation with the Kigali municipality under the direction of the Aegis Trust, an NGO based in the United Kingdom. The Aegis Trust is the initiative of two English brothers, Stephen and James Smith, who initially built a Holocaust center in London in 1995 and then became interested in the Rwandan genocide and founded the Aegis Trust in 2000, seeking to memorialize the Rwandan genocide and use the Rwandan example as a means of preventing further genocides in Rwanda and elsewhere. As the center’s website explains:

Aegis observed that if [Rwanda] is to make a sustainable recovery, memory and education are critical factors. Memory, because survivors need time and space. They need to be heard within their own society and further afield. So too, Rwandan society needs to reckon with its collective conscience, to be clear about what it is remembering and why. Education, because new and emerging generations, on all sides of the genocidal divide, need to feel comfortable confronting the country’s past and absorbing its demanding lessons.Footnote 26

While formally working with the municipality of Kigali, the Aegis Trust put their clear imprint on the Kigali Memorial Centre, which they, “modeled on the Beth Shalom Holocaust Centre”Footnote 27 that they had earlier built in the United Kingdom. As Stephen Smith, director of Aegis Trust, said in a 2004 press release, “We do not create museums for the sake of museums. We create museums to dignify the past, to ensure the historical record and to provide an educational tool for future generations.”Footnote 28 The center’s website claimed that in 2000, “The Aegis Trust then began to collect data from across the world to create the three graphical exhibits. The text for all three exhibitions was printed in three languages, designed in the UK at the Aegis head office by their design team, and shipped to Rwanda to be installed.”Footnote 29

Figure 4 The room of victim photos at the Kigali Memorial Centre

Despite this international origin, the text in the exhibitions clearly reflected the historical narrative promoted by the RPF regime. A panel printed on a sepia-toned photograph of Rwandan children highlighted the significance of clans in pre-colonial Rwanda and argued that Rwandans lived in peace before colonial rule and that colonialism introduced ethnic differentiation:

The primary identity of all Rwandans was originally associated with eighteen different clans. The categories Hutu, Tutsi and Twa were socio-economic classifications within the clans, which could change with personal circumstances. Under colonial rule, the distinctions were made racial, particularly with the introduction of the identity card in 1932. In creating these distinctions, the colonial power identified anyone with ten cows in 1932 as a Tutsi and anyone with less than ten cows as Hutu, and this also applied to his descendants. We had lived in peace for many centuries, but now the divide between us had begun …

Another panel had a photo of Rwanda’s first president, Kayibanda, with an unattributed quote, perhaps from one of his speeches:

The Hutu and the Tutsi communities are two nations in a single state. Two nations between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy, who are ignorant of each other’s habits, thoughts and feelings as if they were the inhabitants of different zones of planets.

Yet another panel stated:

Over 700,000 Tutsis were exiled from our country between 1959–1973 as a result of the ethnic cleansing encouraged by the Belgian colonialists. The refugees were prevented from returning, despite many peaceful efforts to do so. Some then joined the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) who, on 1 October 1990, invaded Rwanda. Civil war followed, which resulted in the internal displacement of Rwandans, many of whom were held in internal refugees camps by the Government of Rwanda. Times were tense.

Here, not only is colonialism blamed for the genocide, but the idea is put forward that the RPF was motivated by noble purposes, founded only after the failure of “many peaceful efforts” to allow repatriation of refugees. The unfounded claim that those internally displaced by the RPF’s attacks on the country “were held in internal refugee camps” deflects negative criticism away from the RPF’s attacks and onto the government that was forced to house and provision more than a million people affected by the war.Footnote 30 The next panel continues the exoneration of the RPF, building on the reality that President Habyarimana exploited social divisions:

The RPF were intent on establishing equal rights and the rule of law, as well as the opportunity for the refugees to return. Habyarimana used the tension to exploit divisions in the population, launching campaigns of persecution and fuelling fear among the people. The war on the Tutsi minority was going largely unnoticed, even though many Tutsi and Hutu opponents of the divisive ideology were in prison, tortured or murdered.

The terminology used in the museum reflects the shift in public discourse about the events of 1994. In the years immediately after 1994, the government, media, and other sources referred to the genocide as itsemba bwoko, literally meaning “ethnic killing,” a new term created out of existing Kinyarwandan words. When referring to itsemba bwoko officials and others often made reference as well to itsemba-tsemba, an established Kinyarwanda term for massacres, acknowledging that while genocide had taken place against the Tutsi because of their ethnicity, many Rwandans were killed by the armed forces because of their moderate political views or caught in the war or in RPF attacks on civilians. The Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, however, used the term jenoside, a Kinyarwanda transliteration of the word genocide that officials began actively promoting several years before the tenth anniversary. Officials argued that itsemba bwoko was not an accurate term to describe what happened in 1994, because the killing was not merely an ethnic massacre but genocide. At the same time, the discussion of itsemba-tsemba was dropped from public rhetoric. A few years later, the regime began to promote another more specific term, jenoside y’Abatutsi, genocide of the Tutsi. This terminology was added to the constitution in 2008 and incorporated into the Memorial Centre.Footnote 31 The Memorial Centre exhibits did mention the killing of moderate Hutu but made no reference at all to massacres carried out by the RPF.

In addition to the museum, with its educational purpose, the center also is a memorial to those killed in the genocide. The municipal government decided to gather together the remains of all those killed in Kigali in 1994. Bodies were exhumed from mass graves throughout the city and brought to Gisozi to be placed in the large crypts built in the gardens surrounding the museum. As the website for the center explained, “The Center provided an opportunity to offer a place in which the bereaved could bury their families and friends, and over 250,000 victims of the genocide are now buried at the site – a clear reminder of the cost of ignorance.”Footnote 32 The clear implication is that the bodies buried at Gisozi are those of genocide victims, but in fact Kigali was the site of protracted battles between the Rwandan Armed Forces and the RPF from April through June 1994, and many civilians were caught in the crossfire. In addition, a large portion of Kigali was under RPF control, where Tutsi enjoyed safe haven but many Hutu faced arbitrary execution or other attacks.Footnote 33 In other words, while 250,000 bodies may be buried at Gisozi, there is no evidence that they are in fact “victims of the genocide.” If this claim were true, then Kigali would have suffered at least a quarter of the casualties in the genocide (if one even accepts the inflated figure of one million dead). Yet the population of Kigali according to the 1991 census was 235,664, and only a minority of that number was Tutsi.Footnote 34 Furthermore, when the genocide began and the civil war renewed, much of the population fled the city. Hence, the basis for the claim of 250,000 genocide victims buried at Gisozi remains entirely unclear.

Sites of Forgetting

A few miles south of the important Catholic center of Kabgayi, near the former regional capital Gitarama in the central part of the country, a house perched prominently on a small hill just off the main highway was left to fall to ruins. Though only one story, the house was spacious by Rwandan standards, and modern looking, spreading in a large U-shape around an open flat lawn. While not demolished, in contrast to many of the homes touched by the genocide, this house was neglected, with many windows broken out and the roof collapsing in some places. No plaque marked the spot, but most Rwandans knew this house, because it was the home of Rwanda’s first president, Grégoire Kayibanda. After being deposed from office in 1973, Kayibanda lived out his last few years here, and this is where in 1976 he died a quiet death.

In the mythology of the current Rwandan regime, Kayibanda holds a special vilified place. He is regarded as the father of the country’s anti-Tutsi ideology, having helped write the Bahutu Manifesto in 1957 and led the Party of the Hutu Emancipation Movement (Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation Hutu, Parmehutu) that championed Hutu majority rule and dominated the country from 1960 to 1973. He is blamed for inspiring the “first genocide” of Tutsi in 1959 with his anti-Tutsi ideas. Kayibanda is also regarded as a stooge of the Europeans, a puppet of the Catholic missionaries who promoted his political ascendancy and the leader who allowed Belgium and other foreign powers to retain their neo-colonial control over Rwanda.

While President Habyarimana justified his removal of Kayibanda as necessary to restore order and promote development, his own rhetoric spoke of “finishing the revolution,” building on the legacy that Kayibanda had begun, but focusing on economic development rather than ethnic exclusion. Habyarimana did not execute Kayibanda but kept him under house rest and, despite rumors that the former president died of starvation and neglect, after his death the house was maintained, the walls kept painted, the gardens tended. Until 1994, travelers along the Kigali–Butare road saw a prosperous, well-kept, but unoccupied home whose upkeep seemed to signal a concession to the First Republic. After the RPF took power, however, the Kayibanda home was abandoned – not destroyed or taken over by an official of the current regime, but left to fall into disrepair, serving as a symbol of the rejection of the ideas that Kayibanda represented.

Just as the landscape of Rwanda is scattered with mass graves and memorials that serve as reminders of the 1994 genocide and highlight its centrality to Rwandan society and politics, the countryside is full of sites, like the Kayibanda home, that have been conspicuously neglected and send an equally powerful message about what the current regime rejects. While mass graves associated with the genocide were carefully marked and tended, mass graves of those killed by the RPF were pointedly ignored and neglected. While genocide massacre sites were marked by plaques and memorials, sites of other massacres were ignored. Kibeho, for example, was a religious pilgrimage site prior to the genocide, where the Virgin Mary was believed to have appeared to several schoolgirls and local peasant farmers.Footnote 35 During the genocide, the Kibeho church was the site of a major massacre early in the genocide, where an estimated 17,500 people were killed.Footnote 36 Both of these events are commemorated at Kibeho. The Catholic Church has constructed a new chapel at the site of the apparitions, while both the church and the government have built memorials – one inside the church building and another at the mass grave in the church yard. (See Figure 5.) Yet Kibeho was also the site of the most publicized RPF massacre in post-genocide Rwanda. Following the RPF rise to power, thousands of internally displaced people (IDP) camped at Kibeho, which was part of the French area of occupation, the Zone Turquoise. When the French left in August 1994, the RPF called upon the IDPs to leave the camps and return to their homes. When people refused, the RPF forcibly closed the camps. RPF soldiers opened fire on the IDPs at Kibeho in April 1995, killing an estimated 2,000–4,000.Footnote 37 Yet Kibeho today has no sign whatsoever of those killed by the RPF. There is no mass grave, no plaque, nor any other indication that a massacre took place at this location.

Figure 5 Kibeho genocide memorial and church

Kibeho, like every other location where the RPF massacred people, serves as a site of forgetting, a site where leaders have pointedly ignored past events and removed their traces in an effort to obliterate their memory. Like “disavowed” memorials to a deposed regime, where traces “are literally or symbolically erased from the landscape either through active destruction or through neglect by the state,”Footnote 38 mass graves of RPF victims are allowed to disappear from public view, growing over with weeds and brush until they are indistinguishable from the surrounding landscape. In many cases, the bodies have simply been disinterred and added to those at genocide mass graves, under the pretense that they too were killed in the genocide rather than victims of the RPF. The RPF regime is certainly not exceptional in avoiding commemorating its own abuses and failures, but in a regime obsessed with memorialization, the choice not to memorialize significant events must be regarded as intentional and politically significant. Considering the brutal dictatorships of Latin America, Elizabeth Jelin noted that, “Erasures and voids can … be the result of explicit policies furthering forgetting and silence, promoted by actors who seek to hide and destroy evidence and traces of the past in order to impede their retrieval in the future … In these cases, there is a willful political act of destruction of evidence and traces, with the goal of promoting selective memory loss through the elimination of documentary evidence.”Footnote 39 Visiting Kibeho or sites of other RPF massacres, one cannot help but note “the presence of an absence,”Footnote 40 the pointed decision to erase the memory of the events that took place there. Jennie Burnet calls this practice of chosen forgetting “amplified silence” and argues that, “While amplified silence has served the RPF regime in the short term, in the long term it has undermined the state’s legitimacy and perpetuated divisions in Rwandan society. Amplified silence prevented Rwandans from discussing the past openly.”Footnote 41

Memorials as Narrative

Just as the official narrative discussed in the previous chapter promotes a particular version of the past, the choice of what to memorialize and what to ignore in post-genocide Rwanda sends a clear message. In contrast to many cases discussed by scholars of memory and memorialization, Rwanda has not been a place where open debate has been tolerated. Political repression has limited the level of public participation in the process of memorial conceptualization. The government has built the vast majority of memorials, and even those built by churches or other groups received strict oversight and had to accord with government expectations. Hence, memorials represent a means for the government to articulate its narrative of the past. They complement the government’s efforts to revise public thinking about Rwandan history, particularly the events of 1994.

The Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre at Gisozi, with its texts and photos presenting Rwandan history, comes closest to presenting a traditional historical narrative. The main points of the narrative are quite consistent with the official discourse: Rwanda’s people historically got along, colonialism divided the country by creating the division between Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa, the post-colonial national leaders bought into the colonial definition of ethnicity and betrayed the interests of the Rwandan people, and the RPF waged war only reluctantly and with the noblest of intentions. Yet in addition to this written narrative, the museum seeks to touch the emotions with the haunting display of photos, abstract art, and open graves. Like the other large memorials at Murambi, Nyarabuye, Nyamata, and Ntarama, Gisozi seeks to demonstrate the horror of the genocide. The display of bodies and bones at most of the sites is meant to shock and offend. The presentation of skulls with machete wounds and women’s bodies with legs spread and a branch inserted seeks to define the nature of the genocide for those who visit, to express the extreme brutality of the crimes. The shock of row upon row of skulls or room after room of ghostly bodies is meant to show the extraordinary numbers of people killed. Bisesero, with its large white monument high above Lake Kivu sends a different message, the fact of Tutsi resistance intended to dispel the idea that Tutsi were merely passive victims of the violence.Footnote 42

To understand these sites fully, though, requires understanding their audience. Average Rwandans rarely visit the sites; the local communities avoid them. As the guides at Nyamata, Ntarama, and Murambi told me – and their visitors books backed them up – only two groups of people came to the genocide memorials: foreigners and repatriated Tutsi. While local people might have questioned the authenticity of the display of bodies and bones, to those unfamiliar with the community, they served as clear evidence of the genocide. As my interview with the Director of Memorials made clear, a primary purpose of these memorials is to serve as proof of the genocide, to refute those who would deny the genocide.Footnote 43 In “proving” the genocide and highlighting its magnitude and brutality, these memorials serve to justify not only the RPF’s leadership of the country but also its tactics. These memorials serve as a backdrop to politicians who seek to explain the need to rein in criticism, to limit civil society and political parties, since they demonstrate the continuing legacies of genocide that might not otherwise be obvious.

Rwanda’s memorialization also has a message for the Rwandan population as a whole. The ubiquity of smaller genocide memorials reminds Rwandans that the genocide occurred throughout the country and keeps the genocide always in mind. Almost every community now has a mass grave or monument commemorating the genocide. One cannot drive far along Rwanda’s highways without passing a memorial site. On the short road from Butare to Gitarama alone includes memorials at the Institute for Scientific and Technical Research at Rubona, the Institute for Agronomic Sciences in Rwanda at Songa, the former royal capital of Nyanza, the market town of Ruhango, and the entrance to the Catholic complex at Kabgayi. During the Week of Mourning, officials pressure the general public to attend ceremonies held at each of these sites, compelling people not only to come to a genocide memorial that they might otherwise avoid but also to participate in a public ritual acknowledging and condemning the genocide.Footnote 44

A crucial purpose of the genocide memorials and commemorations is to reinforce the centrality of the genocide to Rwandan history. With memorials present in most communities, people are regularly reminded of the genocide. Tutsi, particularly rapatriés, are reminded of the peril that they face as a minority group, while Hutu are reminded of the atrocities for which they are responsible and that explain their need to remain silent and accept RPF rule. The pointed refusal publicly to commemorate those killed by the RPF sends a message that these deaths, while perhaps unfortunate, are not socially meaningful. The erasure of the physical traces of RPF massacres underlines the government’s rhetoric about the historical insignificance of deaths outside the genocide as accidental and non-systematic, and thus not worth remembering.

The Director of the Office for Genocide Memorials expressed many of these goals:

There are some people who deny that there was a genocide. But we must not forget, because if we forget it can be very dangerous, not just for Rwanda but for all humanity… We don’t keep memory alive for vengeance but to show people what happened. It is important that future generations know what happened and why. There are those who deny the genocide… You can’t have justice without proofs. We must demonstrate who did what… When you lose someone in a war, it is war. It is not the same thing as genocide.Footnote 45

For the government, then, the memorials serve as proof of the genocide and maintain its centrality. Those who died at the hands of the RPF are merely the unfortunate collateral damage from a war whose deaths do not warrant commemoration.

As I discuss in Chapter 7, the message that the government intends to send through memorials and commemorations does not necessarily dictate how the public itself “reads” them. Mass graves and public remembrances seek to shape popular interpretations of the events of 1994, but individuals’ own experiences affect how they understand the past. Some people do accept the government’s message, but others reject it as inconsistent with their own experience, while still others reinterpret the memorials according to their own needs and ideas. What is clear to nearly everyone, however, is that the government regards the genocide as definitive and a justification for its actions.