There is a group of leaders who have their own project for society, and they want you to join into this project. If you fall outside, they are afraid that you will go in a different direction. There is also a visceral reaction that if you leave these lines that they have set, it could lead us into what happened before. … But you create what you are afraid of.

Introduction to Part I: The RPF as a Janus-Faced Movement

Two widely divergent images have emerged of post-genocide Rwanda and the party that has dominated Rwandan politics since 1994. Development experts praise the Rwandan Patriotic Front’s efficiency, resistance to corruption, and commitment to economic growth.Footnote 1 Many diplomats praise the RPF for promoting national unity, advocating reconciliation rather than revenge, and seeking to eliminate the ethnic differences that have divided the country. The seriousness of purpose of leaders impresses outside observers. For much of the world, the RPF represents a model of good governance in the aftermath of a terrible disaster, not only bringing order and economic development but also altruistically promoting forgiveness and reconciliation in the face of horrific violence.Footnote 2 Journalist Stephen Kinzer, for example, contrasts Rwanda with Somalia and contends that against expectations, Rwanda has become peaceful and unified:

Rwanda … rebelled against its destiny. It has recovered from civil war and genocide more fully than anyone imagined possible and is united, stable, and at peace. Its leaders are boundlessly ambitious. Rwandans are bubbling over with a sense of unlimited possibility. Outsiders, drawn by the chance to help transform a resurgent nation, are streaming in … Rwanda is not being torn apart by civil war, like Somalia, or by criminal violence, like Kenya. Instead, it is stable, its people groping their way toward modernity and liberation.Footnote 3

Paul Farmer, whose organization Partners in Health has worked closely with the government to implement health sector reforms, is a particularly strong defender of the regime:

Today Rwanda has been transformed. Mass violence has not recurred within the country’s borders, and its gross domestic product has more than tripled over the past decade. Growth has been less uneven than in other countries in the region, partly because both local and national governments have made equity and human development guiding principles of recovery. Recent studies suggest that more than one million Rwandans were lifted out of poverty between 2005 and 2010, as the proportion of the population living below the poverty line dropped from 77.8% in 1994 to 58.9% in 2000 and 44.9% in 2010. Life expectancy climbed from 28 years in 1994 to 56 years in 2012. It is the only country in sub-Saharan Africa on track to meet most of the millennium development goals by 2015. Although metrics for equity are disputed, it is an increasingly well known fact that Rwanda today has the highest proportion of female civil servants in the world.Footnote 4

For Kinzer, Farmer, and many others, the RPF’s success at building peace and stability is due largely to the influence of the RPF leader, President Paul Kagame. Kinzer writes that, “President Kagame … has accomplished something truly remarkable. The contrast between where Rwanda is today and where most people would have guessed it would be today in the wake of the 1994 genocide is astonishing.”Footnote 5 Phillip Gourevitch, the most widely-read author on Rwanda, similarly portrays Kagame as a moderate leader who has embraced former adversaries and promoted forgiveness and reconciliation. He cites a genocide survivor referring to her génocidaire neighbors, “It’s because of the President that they don’t kill. Forgiveness came from a Presidential order. If he were not there, we would all be killed.”Footnote 6 Both Kinzer and Gourevitch praise Kagame’s deft management of the economy, having attracted considerable foreign investment, aggressively fought corruption, and brought about impressive economic growth. Kinzer writes that, “Kagame has set out to do something that has never been done before: pull an African country from misery to prosperity in the space of a generation.”Footnote 7

In contrast, among human rights activists and many scholars of Rwanda, a much less sanguine perspective on post-genocide Rwanda prevails.Footnote 8 Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, who raised the alarm early about the 1994 genocide, also denounced human rights abuses perpetrated by the RPF as it fought its way to power and sought to establish authority, and both organizations have remained consistent critics of the post-genocide regime.Footnote 9 A growing body of academic publications based on recent fieldwork conducted in Rwanda portrays a heavy-handed state that uses fines, arrests, and other forms of intimidation to force the population into mobilizing for government programs and implementing far-reaching plans to restructure social relations, economic activity, political engagement, and even personal hygiene.Footnote 10 Long-time Rwanda observer Filip Reyntjens argues that, “The [RPF] regime seeks full control over people and space: Rwanda is an army with a state, rather than a state with an army.”Footnote 11

The contrast between these two perspectives of post-genocide Rwanda could hardly be more stark, yet ample evidence exists to support each. Any reasonable observer of Rwanda cannot ignore the numerous accomplishments of the post-genocide regime. The RPF-led government has consistently employed a discourse of national unity, justice, and reconciliation. Since the suppression of the uprising in northwestern Rwanda in 1998, the country has been free from large-scale violence. Strong promotion of women’s rights has given Rwanda the distinction of having the highest percentage of women in parliament of any country in the world, the first where women are a majority of members of parliament.Footnote 12 The regime has placed considerable emphasis on education, leading to a proliferation of schools at all levels, raising the elementary school completion rate from 51.1 percent in 1991 to 79.0 percent in 2011 and the adult literacy rate from 58 percent in 1991 to 70 percent in 2008. Investments in healthcare have helped to lower child malnutrition from 24.3 percent in 1991 to 18.0 percent in 2008.Footnote 13

Shortly after Kagame became president in 2000, the government released Rwanda Vision 2020, an ambitious economic program “to raise the people of Rwanda out of poverty and transform the country into a middle-income economy” in twenty years.Footnote 14 The government has since aggressively promoted policies to attract international investment, and the economy has enjoyed annual gross domestic product growth rates as high as 11.2 percent. The government has thoroughly embraced neo-liberal economic reforms, privatizing numerous public assets and adopting extensive regulatory reforms to ease international investment. In 2010, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report ranked Rwanda as having the third lowest burden of government regulation and the twelfth most efficient government overall.Footnote 15 Rwanda’s ranking in Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index was 44th in 2015, among the best in Africa and far ahead of any other East African state.Footnote 16 Rwanda was welcomed into the East African Community in 2007 and the British Commonwealth in 2009.Footnote 17

Yet strong evidence also indicates that extensive human rights abuses have simultaneously occurred. The RPF used widespread violence to establish its initial authority, perpetrating massacres, summary executions, and numerous arbitrary arrests in its first years in power, and carrying out a bloody counter-insurgency operation in the northwest in 1997–1998.Footnote 18 Since 2000, even as the RPF has gained an international reputation for competence and moderation, the leadership has used more subtle means to maintain its power, tightly constraining public space and tolerating little dissent, while coercing the general population to implement sweeping social changes.Footnote 19 Security forces regularly harassed, arrested, and even killed civil society activists, journalists, and politicians who dared to criticize the government, while average Rwandans who objected to the apparently arbitrary imposition of onerous new regulations or resisted the regime’s constant mobilization programs (such as those for villagization, constitutional reform, elections, gacaca, public works, and land reform) also faced punishment. Beginning with the First Congo War in 1996, while the level of active violence declined inside Rwanda, the RPF carried out massive attacks on civilians in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where violence and instability continue to reverberate.Footnote 20

In this first part of the book, I explore an aspect of public policy that reveals the Janus-faced nature of RPF rule – transitional justice. I review the government’s diverse programs to shape popular understandings of Rwanda’s past and thus promote a unified national identity. The regime has developed a narrative that emphasizes the historic unity of the Rwandan people, highlights the centrality of the 1994 genocide, and portrays the RPF in a favorable light. It has promoted these ideas through education and propaganda, trials, political reform, and memorialization and commemoration. While the RPF has created these programs in part to promote justice, accountability, and reconciliation, their implementation has also been influenced by the leadership’s suspicion of the Rwandan population and the belief in the absolute necessity that they stay in power. As I explore in the second section of the book, the contradictions in these motivations ultimately undermine their ability to transform Rwandan society.

1 Praise from the head of the United Nations Development Program in Rwanda is typical of the views of many development experts. “Rwanda has made tremendous socioeconomic progress and institutional transformation since the 1994 Genocide. Today Rwanda is a peaceful state enjoying a steady progress toward the achievement of national development goals under a visionary and dedicated leadership.” Aurélien A. Agbénonci, “Introductory Remarks,” Delivering as One: Annual Report 2009, Kigali: United Nations Rwanda, 2010, p. v.

2 C.f., Margee Ensign, “Rwanda at 50: Reflections, Reconstruction, and Recovery,” Huffington Post, July 3, 2012; Michael Fairbanks, “Nothing Good Comes Out of Africa,” Huffington Post, May 3, 2010; Emily Holland, “Dispatches from a Humanitarian Journalist: Dispatch I: Kibuye, Rwanda,” McSweeney’s, September 4, 2007; “Rwanda: Trying to Move on,” Public Radio International’s The World, Jeb Sharp, producer, 2007.

3 Stephen Kinzer, A Thousand Hills: Rwanda’s Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2008, pp. 1–2.

4 Paul Farmer, et al., “Reduced Premature Mortality in Rwanda: Lessons from Success,” BMJ, January 2013, pp.

5 Footnote Ibid, p. 337.

6 Philip Gourevitch, “The Life After: 15 Years after the Genocide in Rwanda, the Reconciliation Defies Expectations,” The New Yorker, May 4, 2009.

7 Kinzer, A Thousand Hills, p. 336.

8 A recent collection of essays in honor of the late Alison Des Forges by a group of twenty-eight Rwanda scholars was uniformly bleak in its portrayal of post-genocide state and society. Scott Straus and Lars Waldorf, eds., Remaking Rwanda: State Building and Human Rights after Mass Violence, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011.

9 Amnesty International, “Rwanda: Reports of Killings and Abductions by Rwandese Patriotic Army, April-August 1994,” AFR 47/16/94, London: Amnesty International, October 19, 1994; Amnesty International, “Rwanda: Human Rights May be the Main Casualty of Tensions in the Rwandese Government,” AFR 47/18/95, London: Amnesty International, August 30, 1995; Des Forges, Leave None to Tell the Story.

10 An Ansoms, “Striving for growth, bypassing the poor: a critical review of Rwanda’s rural sector policies,” Journal of Modern African Studies, 46, no. 1, 2008, 1–32; An Ansoms, “Re-engineering rural society: the visions and ambitions of the Rwandan elite,” African Affairs, 108, no. 431, 2009, 289–309; An Ansoms and Stefaan Marysse, eds., Natural Resources and Local Livelihoods in the Great Lakes Region in Africa: A Political Economy Perspective, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011; Larissa Begley, “‘Resolved to Fight the Ideology of Genocide and all of its Manifestations’: The Rwandan Patriotic Front, Violence and Ethnic Marginalisation in Post-Genocide Rwanda and Eastern Congo,” PhD Dissertation, University of Sussex, March 2011; Burnet, Genocide Lives in Us; Anuradha Chakravarty, Investing in Authoritarian Rule: Punishment and Patronage in Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts for Genocide Crimes, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016; Christopher Huggins, “Seeing Like a Neoliberal State? Authoritarian High Modernism, Commercialization and Governmentality in Rwanda’s Agricultural Reform,” PhD Dissertation, Carleton University, 2013; Bert Ingelaere, “Do We Understand Life After Genocide: Center and Periphery in the Construction of Knowledge on Rwanda,” African Studies Review, 53, no. 1, April 2010, 41–59; Bert Ingelaere, “Peasants, Power and Ethnicity: A Bottom-Up Perspective on Rwanda’s Political Transition,” African Affairs, 109, no. 435, 2010, 273–292; Andrea Purdeková, Making Ubumwe: Power, State, and Camps in Rwanda’s Unity-Building Project, New York: Berghan Books, 2015; Marc Sommers, Stuck: Rwandan Youth and the Struggle for Adulthood, Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2012; Susan Thomson, Whispering Truth to Power: Everyday Resistance to Reconciliation in Post-Genocide Rwanda, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

11 Filip Reyntjens, “Constructing the Truth, Dealing with Dissent, Domesticating the World: Governance in Post-Genocide Rwanda,” African Affairs, 2010, 1–34, citation p. 2. See also Filip Reyntjens, “Rwanda Ten Years On: From Genocide to Dictatorship,” African Affairs, 103, 2004, 177–210; and René Lemarchand, “Bearing Witness to Mass Murder,” African Studies Review, 48, no. 3, December 2005, 93–101.

12 Timothy Longman, “Rwanda: Achieving Equality or Serving an Authoritarian State?” in Gretchen Bauer and Hannah Britton, eds., Women in African Parliaments, Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2005.

13 “Rwanda,” World Bank, http://data.worldbank.org/country/rwanda.

14 Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, “Rwanda Vision 2020,” Kigali: Government of Rwanda, July 2000.

15 World Economic Forum, “The Global Competitiveness Report 2010–2011,” http://gcr.weforum.org/gcr2010/, 2010.

16 Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index,” www.transparency.org.

17 “Keep Looking Ahead Rwanda,” The Economist, January 13, 2007; Josh Kron, “Rwanda Joins British Commonwealth,” New York Times, November 29, 2009.

18 Des Forges, Leave None to Tell the Story, pp. 692–735; Amnesty International, “Rwanda: The Hidden Violence: ‘Disappearances’ and Killings Continue, London: Amnesty International, June 22, 1998.

19 Chakravarty, Investing in Authoritarian Rule, contends that “Although its tight grip in the early transition years depended on the use of blatant force through killings and arbitrary arrests, the RPF has entrenched itself over the years, becoming thoroughly able to project power at the grassroots without over-reliance on these tools of repression” (p. 2).

20 Jason K. Stearns, Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, New York: Public Affairs, 2011; René Lemarchand, The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009; Filip Reyntjens, The Great African War: Congo and Regional Geopolitics, 1996–2006, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

To contest the past is also, of course, to pose questions about the present, and what the past means in the present. Our understanding of the past has strategic, political, and ethical consequences. Contests over the meaning of the past are also contests over the meaning of the present and over ways of taking the past forward.

In the aftermath of the 1994 genocide, the government put into office in Rwanda by the victorious Rwandan Patriotic Front undertook a wide-reaching program of social reform aimed, in part, at preventing future ethnic violence. Among their social programs, the post-genocide government placed a major emphasis on promoting education, believing that low levels of education and high illiteracy had fostered ignorance in the population that increased its vulnerability to manipulation by those who wished to foment ethnic violence. A better-educated population, government officials reasoned, would be more capable of seeing through the false consciousness that, from the perspective of Rwanda’s new rulers, ethnicity represented. The government thus sought not only to increase enrollments in schools from primary through university levels but also to increase the quality of education by revamping the curriculum and raising standards for teachers.Footnote 1 The results are impressive, with rates of enrollment by primary-age children rising from 66 percent in 1991 to 96.5 percent in 2012, and enrollment in secondary schools rising from 8 to 28 percent of eligible youth during the same period.Footnote 2

At the same time, however, the Ministry of Education struggled over the appropriate content of education, particularly in the area of history. Shortly after taking power, the government placed a moratorium on the teaching of history in schools. Believing that distorted historical narratives promulgated by schools since the colonial era had promoted the anti-Tutsi ideology that drove the genocide, the Ministry of Education determined that history courses would be removed from the secondary school schedule until a new curriculum could be developed that corrected the distortions of the previous history curriculum.Footnote 3

Writing a new history for Rwandan schools proved to be a challenging task. History in post-genocide Rwanda is a highly sensitive topic in which the government has expressed a clear vested interest. Those who endeavored to write history entered a political minefield in which their analysis was constrained by the government’s expectations of a “correct” version of history. Yet even those historians who shared the government’s vision of the past were confronted by the sheer magnitude of the task of developing a new narrative entirely at odds with ideas previously accepted as fact by the majority of Rwanda’s people. Although a group of both professional and amateur historians had dedicated considerable attention since 1994 to publishing new interpretations of Rwanda’s past, when conferences were held at the National University of Rwanda (NUR) in 1998 and 1999 to begin the process of developing a definitive history of the country, participants felt that insufficient scholarly groundwork had been laid.

The research project that I participated in from 2001 to 2003 to study Rwandan secondary schools found that participants in both individual and focus group interviews – whether teachers, administrators, parents, or students – uniformly expressed a strong interest in bringing history back into the schools. But when we received funding to work with the Rwandan government to develop a new history curriculum and launched a curriculum development project in 2004, we confronted a contradiction inherent to official attitudes toward history in Rwanda today. The desire to foster critical thinking skills that would allow students to reason for themselves and thereby be capable of resisting manipulation ran into direct conflict with the idea that there was a “correct” version of Rwandan history that anyone who supported the ideals of reconciliation and peace must adopt. In two years of working with a diverse group of high school teachers and students, education and history professors, government officials, and civil society activists, we found repeatedly that the articulated support for the idea of history as a series of problems and opportunities for debate collided with the reality of a highly authoritarian society. Participants appreciated the idea of free discussion of history, but most did not feel sufficiently free in Rwanda’s contemporary political climate to challenge the newly developed orthodox version of Rwandan history. Debate could be tolerated, but only if it led to pre-determined answers.Footnote 4

Memory, History, and Identity

That national histories are not sets of established facts but rather socially constructed narratives of the past is widely accepted in academic circles today. Popular historical narratives are not unbiased descriptions of events but subjective accounts shaped by the present needs and interests of societies. While history may be “a fable agreed upon,”Footnote 5 the manner in which historical narratives are constructed has social and political significance. The process by which societies collectively develop and accept myths about the past that become their national history is not benign. The statement attributed to Winston Churchill that, “History is written by the victors,” emphasizes the ways in which the powerful shape history for their own political purposes. Not only do the victors in great wars interpret history in a way that ennobles their cause and vilifies their defeated enemies, but social victors – the rich and powerful who dominate societies – write history to justify their domination and undercut the pretensions to power of society’s losers.Footnote 6 The construction of historical narrative thus has a coercive nature.

Scholars have employed the concept of collective memory to enlighten discussions of historical narratives and their social impact. Maurice Halbwachs first developed the idea of collective memory in the 1920s, arguing that an individual’s memories are developed in a social context that shapes the content of memory.Footnote 7 Applying the lens of social psychology, Halbwachs contended that, “the mind reconstructs its memories under pressure of society. … Society from time to time obligates people not just to reproduce in thought previous events of their lives, but also to touch them up, to shorten them, or to complete them so that, however convinced we are that our memories are exact, we give them a prestige that reality did not possess.”Footnote 8 Even events that we have personally experienced are shaped by the society within which we live.

The concept of collective memory gained new currency in the 1980s when Pierre Nora applied it to the study of nationalism, looking at the “sites of memory” – the memorials, holidays, anthems, and other symbols – that helped shape French Republican identity.Footnote 9 Nora’s analysis contributed to a growing literature that regards nationalities as “imagined communities,” in which people are tied together not by any real fundamental social, cultural, or historical unity but rather by the idea that they share a common connection.Footnote 10 Eric Hobsbawm argued that nations cannot ultimately be defined by racial differences or such cultural differences as language or religion but rather by a sense of shared history, “the consciousness of having belonged to a lasting political entity … a ‘historical nation.’”Footnote 11

Developing a collective historical memory is key to developing national identities, but the process carries coercive tendencies. To build a shared national identity, a population must be re-educated and may ultimately need to be forced into accepting a particular vision of the past. Karl Deutsch’s classic study of nationalism in the aftermath of the Second World War noted that nationalism involves, “processes of social learning and control which are particularly subject to risks of pathological developments and trends to self-destruction.”Footnote 12 Those engaged in a nationalist project seek to promote a particular collective memory about the past that serves to support their definition of national identity. Such nationalist projects are notoriously intolerant of open debate and discussion. As Katharine Hodgkin and Susannah Rodstone argue in the epigraph, arguments about the past reflect conflicts over the present.Footnote 13 Nationalists who seek to marshal the past to promote a unified national identity do so ultimately to achieve a particular political goal, and as such they generally cannot tolerate individuals and ideas that seek to complicate the past or challenge aspects of the proposed collective memory.

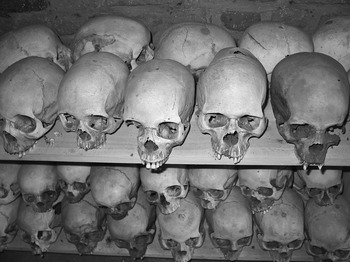

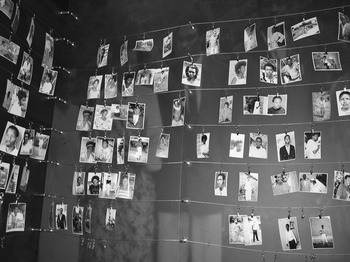

In Rwanda, the post-genocide government has actively sought to shape collective memory, using a focus on the 1994 genocide as a focal point for constructing a new national identity. In subsequent chapters, I explore the various mechanisms being used to build collective memory, such as genocide memorials and genocide trials. In this chapter, I focus on the more obvious aspects of shaping collective memory, the development and promulgation of a new historical narrative. I first review the ways in which historical narratives served to justify the Rwandan genocide. While the historical myths central to the genocidal ideology did not push most people to participate in the violence, historical narratives did serve to delineate the distinctions between Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa without which the genocide could not have occurred, and for a small core group, the ideas that Tutsi did not belong in Rwanda and that Hutu needed to redeem their besmirched honor motivated participation. As I then analyze, since taking power in 1994, the RPF regime and its supporters have undertaken a major project to re-write Rwandan history. They have completely rejected previous historical narratives and sought to develop new ones; but these are no more based on historical fact than those that preceded them. Just as previous history overemphasized the centrality of ethnicity, the more recent history overemphasizes the historical unity of Rwanda’s population, inaccurately denying any historic social significance at all to ethnicity. More problematic is the attempt to re-imagine the RPF in heroic terms, seeking to expunge from popular memory abuses carried out by the RPF and portray RPF violence as motivated exclusively by the attempt to end genocide and bring peace and democracy to Rwanda. As I will develop in later chapters, this portrayal of the RPF – which is directly at odds with the lived experience of many Rwandans – ultimately undermines the public’s willingness to embrace the new official historical narrative.

History, Ideology, and the Rwandan Genocide

History played a key role in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. The ideology used to justify the genocide drew on a historical narrative developed during the colonial period that saw Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa as clear and distinct racial groups and characterized Tutsi as recent arrivals in the region which had conquered and dominated the other groups. Based on this narrative, the instigators of the genocide asserted that Tutsi were foreigners who had no right to be in Rwanda and needed to be feared and opposed because of their history of dominating the majority Hutu.Footnote 14

While the exact meaning of the categories “Hutu,” “Tutsi,” and “Twa” in pre-colonial Rwanda remains contentious, most scholars today agree that they were not ethnic groups in the modern sense. Current scholarship indicates that the terms reflected a status difference even in pre-colonial times,Footnote 15 but the groups shared a common culture, spoke the same language, Kinyarwanda, and lived in integrated communities or in close proximity. Furthermore, Hutu and Tutsi were somewhat flexible categories, since intermarriage was possible and a family’s status could change as their fortunes rose or fell.Footnote 16 The identities emerged as centralizing monarchies sought to extend their control by implanting a Tutsi aristocracy throughout the territory as representatives of the crown.Footnote 17 Patterns of migration within the region were complex, and each group included both recent migrants and those long in Rwanda.Footnote 18 Hutu or Tutsi were only one of a number of significant identities for Rwandans along with lineage, region, clan, and sub-clan.

When European missionaries and colonial administrators arrived in Rwanda around the turn of the twentieth century, their perspective on Rwandan society was shaped by then-contemporary European ideas about race and identity. Ignoring the actual complexity of identity within Rwanda, they believed that the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa identities were paramount, regarding them as three distinct ethnic, or even racial, categories. Influenced by ideas of social Darwinism, that considered identity not merely social but biological, with each ethnic and racial group naturally possessing specific talents and characteristics, they saw in the Tutsi a superior Hamitic group, distant relatives of Caucasians who were more intelligent than their fellow countrymen and therefore natural rulers. They regarded the Hutu as a Bantu group, sturdy and simple, best suited for physical work such as farming, while they considered the Twa a Pygmy group, inferior, lazy, and untrustworthy, never having evolved beyond hunting and gathering.Footnote 19

The Tutsi elite played on European prejudices to their own advantage, helping develop a historical narrative of Rwanda’s past adapted to European racist assumptions. As Des Forges wrote:

Not only did they use European backing to extend and intensify their control over the Hutu – whose faults they exaggerated to the gullible Europeans – they also joined with the Europeans to create the ideological justification for this exploitation. … In a great and unsung collaborative enterprise over a period of decades, European and Rwandan intellectuals created a history that fit European assumptions and accorded with Tutsi interests.Footnote 20

According to this history, the Twa, the region’s original inhabitants, were subdued by Hutu who migrated from the west at the beginning of the first millennium. The Tutsi supposedly arrived from the northeast over a millennium later bringing with them cattle and a complex, centralized political system and, because of their natural intelligence and military superiority, subdued the other groups.Footnote 21

Far from being merely of academic interest, this ideologically shaped historical narrative became a basis for public policy. The German and Belgian administrations established a system of indirect rule that left the Rwandan monarchy in place to facilitate their administration of the territory. At the same time, they reshaped the existing system, consolidating Tutsi social position and centralizing the power of the monarchy, eliminating existing vestiges of Hutu power. Much of Rwanda, and particularly the Hutu, experienced what Catharine Newbury has called “dual colonialism” of both the colonial administration and the central court.Footnote 22 Both the government and Christian churches reserved most educational and salaried employment opportunities for Tutsi. In the 1930s, the colonial administration required all residents to carry identity cards that listed their ethnicity, hence administratively fixing group identities and eliminating their flexibility.Footnote 23 These policies effectively increased the salience of Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa identities over other social identities, since they helped determine life chances, while the ideology provided different historical imaginaries for the groups that ultimately helped to convert them into ethnic identities.

For much of the colonial period, the myth of Tutsi conquest and superiority served successfully to justify the group’s privileged position. But following the Second World War, colonial administrators and missionaries influenced by social democratic political ideas began to change their sympathies to the Hutu, whom they now characterized as an oppressed working class who had suffered under the yoke of Tutsi domination for centuries. The same erroneous historical narrative that had been used to support Tutsi dominance was now used to support the emergence of a Hutu counter-elite and justify a shift in political control to Hutu hands following anti-Tutsi violence in 1959. The democratic principle of “majority rule” got distorted in Rwanda to mean rule by the Hutu ethnic majority, and after independence, the government of Kayibanda continued to draw on the historical narrative of Tutsi conquest and exploitation of the Hutu to justify his own consolidation of power as the defender of Hutu interests.Footnote 24 The false histories of migration as the source of ethnic differentiation in Rwanda and of Tutsi as the long-time oppressors of Hutu continued to be taught in schools after independence.

After Juvénal Habyarimana became president in a 1973 coup, he sought to quell ethnic violence by implementing an ethnic quota system that limited Tutsi access to education and employment, but the basic ideology of Hutu majority rule remained unchanged. When both an internal movement for democratization and the invasion by the Rwandan Patriotic Front challenged the Habyarimana regime in the early 1990s, his supporters returned to the ideology of the Kayibanda years and sought to regain popular support by recasting themselves as the defenders of the Hutu majority against an attempt to re-establish a minority Tutsi dictatorship. They used targeted violence against the Tutsi to heighten ethnic polarizationFootnote 25 and undermined their critics by portraying them as traitors to Hutu interests. This strategy of using ethnic violence to mobilize Hutu support ultimately culminated in the 1994 genocide.Footnote 26

The ideology used to justify the 1994 genocide and inspire popular participation drew heavily on the historical narrative developed during colonial rule. The message was promulgated as propaganda through meetings of Habyarimana’s political party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (Mouvement Révolutionaire National pour le Développement, MRND), and even more extreme Coalition for the Defense of the Republic (CDR), extremist publications, and both the official radio station, Radio Rwanda, and the ostensibly independent Radio-Television of the Thousand Hills (Radio-Télévision Libre des Milles Collines, RTLM), founded by MRND and CDR supporters. The ideology claimed that Tutsi were aliens who did not belong in Rwanda. In a notorious November 1992 speech to an MRND meeting in Gisenyi Prefecture recorded on a cassette and much replayed, Léon Mugesera, the prefecture’s party vice-president, said of members of the largely Tutsi Liberal Party, “I am telling you that your home is Ethiopia, that we are going to send you back there quickly, by the Nyabarongo” [a tributary of the Nile].Footnote 27 Another major theme was the history of Tutsi conquest and the need for Hutu to revenge their humiliation and emasculation at Tutsi hands. Mugesera asserted that, “At whatever cost, you will leave here with these words … do not let yourselves be invaded. … I know you are men … who do not let themselves be invaded, who refuse to be scorned.”Footnote 28

For those authors who regard the 1994 Rwandan genocide as a mass uprising in which huge portions – perhaps a majority – of Hutu participated, the genocidal ideology and its historical narrative are key to understanding popular support for the killing campaign. Mahmood Mamdani, for example, portrays the Rwandan genocide as unique because of its mass nature and extensive popular participation.Footnote 29 He seeks in his text to “make popular agency … thinkable,”Footnote 30 and contends that the genocide was deeply rooted in the history developed in the colonial era. What happened in Rwanda, “was a genocide by those who saw themselves as sons – and daughters – of the soil, and their mission as one of clearing the soil of a threatening alien presence.”Footnote 31 Jean-Pierre Chrétien emphasized the role of hate radio in disseminating the message that the Hutu needed to defend themselves against Tutsi trying to re-establish feudalism.Footnote 32

My own experience in Rwanda just prior to the genocide and my subsequent field research on the genocide (particularly the research I conducted in 1995–1996 for the book Leave None to Tell the Story), convince me that the level of popular participation in the genocide is commonly over-estimated and the role of ideology is exaggerated. Relatively small groups of committed (and trained) killers carried out most of the major massacres at churches, schools, and other central locations before mandatory participation in security patrols and roadblocks implicated a larger portion of the population. Many Hutu men participated in the patrols and roadblocks quite reluctantly, and most of those who participated were not involved in killing. Even those who did participate in the killing, however, were not necessarily driven by a deep hatred of Tutsi whipped up by the genocidal ideology. My own research confirms the findings of Scott Straus’s interviews with confessed genocide perpetrators that people participated primarily out of fear created by the RPF invasion of the country and fear of the consequences of resisting orders by authorities to kill.Footnote 33 Lee Ann Fujii emphasizes the importance of social networks to explaining participation in the genocide, another factor where the ideology mattered little.Footnote 34

Nevertheless, the historical narrative about Rwanda’s past and the ideology that drew upon it were significant to the genocide in several ways. Straus’s conclusion that “an ‘ideology of genocide’ did not drive participation in the genocide”Footnote 35 seems accurate for the vast majority of Rwandans involved in the genocide, but many of the core group of committed killers and those who organized the genocide seem to have been influenced by ideas about a history of oppression and humiliation. For political and social leaders who found their authority slipping away in the early 1990s, the idea of a Tutsi conspiracy made sense. Like other African leaders, Habyarimana developed a neo-patrimonial structure in which he gained support from powerful individuals – principally Hutu from his home region in the north, but also others who were willing to back him – in exchange for opportunities, such as the chance for personal enrichment through embezzling public funds. When the democracy movement challenged this patrimonial elite, their response was not to admit to their own corruption, incompetence, and brutality but to question the motives of those who threatened their power. Because of discrimination, Tutsi were mostly excluded from the elite and widely supported the opposition. Leaders of the regime could thus dismiss the reform movement as a Tutsi conspiracy, particularly when a largely Tutsi army, the RPF, was invading the country. While some Hutu Power leaders may have embraced the ideology of genocide cynically as a tool to motivate popular support, many intensely hated Tutsi. They sincerely believed in the history of Tutsi conquest and domination and deemed themselves the defenders of Hutu interests against a malevolent power-hungry foreign presence on Rwandan soil. The anti-Tutsi ideology’s historical narrative may not explain most popular participation, but it does seem to have motivated many elite participants.

The historical narrative made an even more significant contribution to the genocide, however, in defining the very identity of victims and perpetrators. For scholars, the constructed nature of identities in Rwanda is particularly obvious. Hutu and Tutsi share the same territory and have a common language and culture. Even if claims of physical distinctions between the two groups had historical merit, which they do not, the historic flexibility of group membership and the frequency of intermarriage would have eliminated the reliability of judging individuals by their appearance. What distinguishes the two groups, ultimately, is the idea that they have different historical origins. The fact that historical and anthropological research disproves the assertion that the groups originated through separate migrationsFootnote 36 was politically less significant than the fact that people believed that the two groups were distinct. Jan Vansina’s claim that, “an ethnic group is a group of people who believe erroneously that they share a common history,”Footnote 37 is quite telling in the Rwandan case. The belief that Hutu and Tutsi had different histories ultimately served to distinguish the groups from one another. Long after any occupational differentiation had disappeared, long after Tutsi had lost the reins of power in Rwanda, what separated them from Hutu was a belief in their difference rooted in the historical narrative of separate origins. Colonialists did not invent Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa as categories, but they worked with Tutsi elites to develop a history that endowed the groups with distinct origins and made it possible to think about them as separate races. This distinction, rooted in a historical narrative, ultimately made the genocide possible by delineating the boundaries of group membership.

The Official Historical Narrative

After the RPF swept to power in July 1994, tens of thousands of Tutsi who had been living as refugees, primarily in Uganda, Zaire, and Burundi, began flooding back into Rwanda. These repatriated Tutsi, widely known in Rwanda as the rapatriés, or returnees, had varying experiences abroad. Many had lived in exile for more than three decades, and a large portion was born abroad and had never set foot in Rwanda. Many refugees grew up in the limited confines of camps – particularly in Uganda – but some enjoyed considerable opportunity and prospered in their adopted lands, as in Congo where many Tutsi made successful careers in trade. Despite their diverse backgrounds, most Tutsi refugees shared, to at least some extent, a common vision of Rwanda and its past that was at sharp variance with the historical narrative widely accepted within Rwandan territory at the time. As Liisa Malkki has demonstrated through her perceptive study of Burundian Hutu refugees in Tanzania, the constructed memory of their homeland can be a powerful social force among refugees.Footnote 38 In the perspective of the Tutsi refugees, the Rwandan population had been unified prior to colonialism, and the colonial state and the Catholic Church were largely to blame for the persecution and exclusion of the Tutsi. Corrupt post-independence governments worked in league with foreign powers to manipulate the uneducated and gullible population to prevent the return of Tutsi to their rightful place in Rwandan society. The idea of Rwanda as homeland remained central to the refugee community’s identity, and the desire to return was powerful, particularly during periods when the Tutsi faced discrimination because of their outsider status, as in the second Obote regime in Uganda in the early 1980s.Footnote 39 As Gerard Prunier wrote, “As the years passed and memories of the real Rwanda began to recede, Rwanda slowly became a mythical country in the refugees’ minds.”Footnote 40 For the young who had no personal experience of Rwanda, “Contrasting an idealized past life with the difficulties they were experiencing, their image of Rwanda became that of a land of milk and honey. Economic problems linked with their eventual return, such as overpopulation, overgrazing or soil erosion, were dismissed as Kigali regime propaganda.”Footnote 41 As Malkki suggests, the context in which refugees live affects the degree to which they are driven by collective memory.Footnote 42 The RPF had its roots in the refugee camps of southern Uganda, where life was hard and refugees faced repression. The experience of persecution and limited opportunity shaped the refugees’s view of their own past and the conditions that had forced them to flee into exile. Those who emerged to lead the RPF were motivated by a vision of the past in which the Tutsi were unjustly persecuted.

When the RPF took power in Rwanda, the returned refugees viewed Rwanda through the framework of the collective memory they had developed abroad but found a population whose understanding of the past was quite different from their own. The RPF and its supporters correctly perceived that history had been distorted and used to mobilize the population and enable the genocide.Footnote 43 To achieve a durable peace, they recognized a need to re-educate the population about the country’s history and replace the previous historical narrative with a new narrative in which Tutsi were not foreign invaders but sons and daughters of the Rwandan soil. Immediately after taking power, the government placed a moratorium on the teaching of history in Rwandan secondary schools, while a group of repatriated intellectuals – including government officials, professors, and other intellectuals, such as priests – began to work on revising Rwanda’s formal history. Scholars with strong international reputations, such as Paul Rutayisire, Gamaliel Mbonimana, Faustin Rutembesa, Célestin Kalimba, and Déogratias Byanafashe, most of whom had been professors in Burundi or Zaire, sought to introduce their ideas to a new Rwandan audience.Footnote 44 As Jean Nizurugero Rugagi asserted, “The current and urgent task for the historian is to place before the eyes of Rwandans and before international opinion the authentic course of Rwandan history to better denounce the manipulation that it experienced.”Footnote 45 Dominican Father Bernardin Muzungu founded a quarterly journal, Lumière et Société, focused on correcting understandings of the Rwandan past, the Center for Conflict Management at the NUR in Butare undertook research on issues such as the migration of people into Rwanda and the historic sources of ethnic conflict, and major conferences on the history of Rwanda were organized at the NUR in 1998 and 1999. Government officials in their public addresses, the national radio in both news reports and special programing, and various newspapers and magazines have regularly discussed both Rwanda’s recent and more remote history, using the same historical narrative as the historians.Footnote 46 In the remainder of this chapter, I provide a brief overview of the major themes raised in both the academic historical works and official government discourse.

The Essential Unity of the Rwandan People

The fundamental unity of Rwanda’s people in pre-colonial times is a major theme of the new historical narrative. The scholarship generally does not pretend that the region was entirely peaceful, as kingdoms rose and fell and various individuals and groups vied for political power, but conflicts did not occur along lines of identity. In fact, the narrative challenges the idea that ethnic divisions have a historic basis. Scholars draw on linguistic analysis and archeology to demonstrate that patterns of migration into Rwanda were complex and do not explain the emergence of the country’s ethnic groups.Footnote 47 The fact that clans cut across ethnic lines is raised as proof of the historic unity of the three groups.Footnote 48 The shared use of the Kinyarwanda language is offered as evidence of the cultural unity of the Rwandan people,Footnote 49 as is the unifying belief in a high god, Imana.Footnote 50 President Kagame has often asserted the unity of pre-colonial Rwandans, as in a 2003 speech in San Francisco, in which he stated, “The Bahutu, Batutsi, and Batwa were Banyarwanda until the colonial adventure.”Footnote 51 Pre-colonial Rwanda was effectively a nation state, because it had a single national identity and clearly defined territory,Footnote 52 which is said to have been considerably larger than the boundaries of Rwanda set in colonial times, encompassing much of eastern Congo and southern Uganda, a fact used to justify modern incursions into Congo.Footnote 53

The narrative contends that while the categories Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa existed before colonialism, they emerged within Rwanda rather than through migration. Oral sources are cited to suggest that Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa come from common descent. According to Rwandan myths, the three social groups are descendants of the children of one father. Imana (God) gave them each milk to guard. Gatwa drank his milk, Gahutu spilled his, and only Gatutsi kept his milk safe, which is why Imana put Gatutsi in charge of his brothers. The story “shows that in the ancestral tradition, what we currently call ethnicities are not a question of race but of ‘wealth and social rank.’ In effect, the story speaks of three brothers, not of three races.”Footnote 54 In pre-colonial Rwanda, the three groups lived in harmony, and their relations were not grossly unequal, with each fulfilling a defined social and economic function. In particular, the relationship between Hutu and Tutsi was not feudal, as colonial scholars purported, because relations were reciprocal and mutually beneficial.Footnote 55 Many writers argue that Rwanda was like a large extended family with diverse members nevertheless intimately tied together. “It was on this natural line that national unity was grafted as a larger extension of the family. In this way, the king was considered not only as the political chief, but above all as the ‘supreme patriarch of all families.’”Footnote 56

The idea that the monarchy served to unify Rwandans of all groups is key to the narrative. The royal Nyiginya clan gradually centralized its rule over the Rwandan population in the centuries before colonialism. “The result of this centralization and this increased uniformity of the management of the country was a consciousness of the unity of the population. One king, one law, one people – such was Rwanda in this pre-colonial ‘Nyiginya’ period. This step of development of the country was the supreme realization of Rwanda as a family whose members were named the Rwandans or Rwandan people.”Footnote 57 The king was above ethnicity. As a presidential commission on Rwanda’s national unity concluded, “The King was the crux for all Rwandans. … [A]fter he was enthroned, people said that ‘he was no umututsi anymore,’ but the King for the people. … In the programme of expanding Rwanda, there was no room for disputes between Hutus, Tutsi and Twas. The King brought all of them together.”Footnote 58 In sum, “The Rwandans constitute one ethnicity, not three, and have the same origin, a common biological relationship due to the numerous intermarriages over the millenniums.”Footnote 59

The Divisive Role of Colonialism

If Rwandans were historically a unified people, the narrative clearly blames colonial rule for dividing the population, particularly along ethnic lines.Footnote 60 As Gérard Nyirimanzi writes, “The current crisis has a cause exterior to our past: the racism inculcated in our united people for centuries by the colonizer.”Footnote 61 The Catholic Church began the practice of ethnic segregation by establishing schools for Tutsi,Footnote 62 and the colonial administration then adopted the idea of ethnic differentiation.Footnote 63 Missionaries and others developed a historical narrative that sought to explain the different ethnic groups but that actually created the myths that gave the divisions social meaning. “Colonial historiography not only created cleavages between three social categories but, more seriously, conferred on them an ancient existence. The differences between these entities, rather falsified and unduly important, are explained in reference to the different historical origins.”Footnote 64 The colonial idea that Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa were three separate racial groups that migrated into Rwanda at different times became the basis of colonial policy, and priests, teachers, and administrators ultimately duped the Rwandan population into believing the veracity of the racial origins of Rwanda’s differences.Footnote 65 As Michaël Kayihura states, “The Western historians, ethnographers, and anthropologists accustomed us to a certain number of physical, moral, social, and cultural stereotypes, about which the least that one can say is that they have had a long life, since they still remain in the work of certain post-colonial authors.”Footnote 66

The power and benefits that came to the Tutsi during the colonial period were not due to their own actions but part of the colonial strategy of domination. Once the Tutsi began to seek to wrest control of their country, the colonial rulers switched support to the Hutu in a cynical bid to retain as much power as possible. The Europeans in Rwanda created an “exacerbation through words and acts of the differences between Hutu and Tutsi, by the colony and the mission. The Roman tactic of ‘divide et impera’ (divide to better manipulate) was chosen to prevent the independence of Rwanda. To do this, it was necessary to raise up the Hutu who didn’t ask for it against the Tutsi who demanded it.”Footnote 67 Cynical colonial manipulations cast the Tutsi as arrogant, dominating foreigners. “After the alliances were changed, the Tutsi were abandoned by the colonizers for having committed the fault of demanding the independence of their country, what were previously Tutsi qualities became faults or, more exactly, the opposite of an asset.”Footnote 68

Even well-meaning colonials, such as progressive priests, acted out of a misunderstanding of the Rwandan situation. Flemish priests saw in the Hutu a working class like the Flemish and equated the Tutsi with arrogant Walloons who had historically dominated Belgium. They saw their fight for the Hutu as a fight for justice. “In this hope for justice, these young Flemish forget the great majority of Tutsi who lived in a low social condition at the same level as the Hutu.”Footnote 69

The History of Genocide and Post-Independent Governance

According to the official narrative, the uprising of 1959 was not, as previously contended, a “revolution” but instead the first instance of genocide in Rwanda’s history.Footnote 70 This first instance of ethnic violence in Rwanda’s history was due directly to European manipulations, as colonial administrators, missionaries, and others feared losing their control to a radicalized Tutsi political class who would not have allowed neocolonial domination. A key idea in the narrative is that colonial and post-colonial manipulation distorted democracy in Rwanda. Majority rule came to be understood not as government by the political majority but as rule by the ethnic majority, the Hutu. “The identification of the mass as only the Hutu was the fatal error for the country. This logic culminated in negating purely and simply the nationality of all Tutsi and ignored the existence of the Twa. We already have here the premises of the genocide of 1994.”Footnote 71

The First and Second Republics are understood as pawns of neo-colonial authority. The Hutu who took power were handpicked by the Europeans and betrayed the interests of the Rwandan people for their own personal benefit. “The two first republics were simply extensions of colonization by imposed ‘natives.’”Footnote 72 “The Rwandan social order created by colonization endured more than 30 years in the two first republics.”Footnote 73

Violence against Tutsi began in 1959, and the governments of both Kayibanda and Habyarimana must also be understood in light of this violence. Nyirimanzi’s reference to, “the catastrophe that befell our country beginning in 1959 and the culmination of which took place in 1994,”Footnote 74 is typical in regarding the period of 1959–1994 as a continuous time of violence against the Tutsi, gradually and inevitably building toward the 1994 genocide.Footnote 75 Failure to hold anyone accountable for the earlier violence made possible the genocide in 1994. The anti-Tutsi ideology and policies of the regimes completely overshadow any other policies, such as the focus on economic development.Footnote 76 Issues not related to ethnic violence are glossed over or entirely ignored. For example, Jean-Damascène Ndayambaje writes that, “Violence by the Parmehutu Party against the Tutsi marked the entire period 1959–1973,”Footnote 77 ignoring the actual periodic nature of the violence and the general absence of ethnic violence between 1965 and 1973. The history of both republics is reduced to the aspects relevant to ethnic discrimination and ethnic violence, as though nothing other than identity issues were politically relevant.Footnote 78 As Kagame has said, “The period of 1959 to 1994 is indeed a history of genocide in slow motion.”Footnote 79

The Centrality of the Genocide

The genocide is the focal point of Rwanda’s current historical narrative. Much as the previous regimes referred endlessly to the 1959 “revolution” to justify their actions and interpreted contemporary history in light of this uprising against Tutsi and colonial oppressors, the RPF regime has identified the genocide as the key event against which all Rwandan history before and since must be considered. Colonial history is seen as laying the groundwork for genocide,Footnote 80 and the First and Second Republics are understood to have built inevitably toward the 1994 genocide. President Kagame and other politicians regularly refer to the genocide as the primary source of Rwanda’s ongoing challenges and as justification for many current government policies. Kagame began his 2003 San Francisco speech with the line, “There is no greater crime than genocide,”Footnote 81 using the genocide to frame all of his subsequent remarks. The RPF claims considerable moral authority for having stopped the genocide, and the threat of renewed genocide justifies many ongoing government policies.

The historical narrative offers an interpretation of the genocide that emphasizes its mass popular nature and its brutality. The government and its supporters have consistently insisted on the largest possible number of victims – usually over one million – to emphasize the very serious nature of the genocide.Footnote 82 The editors of Cahiers Lumière et Société assert (without supporting evidence) that since 1959 two million people have been killed in Hutu–Tutsi violence in Rwanda.Footnote 83 Along with a large number of victims, the narrative portrays the genocide as an event in which nearly every Hutu in the country was caught up and that involved extraordinary depravity. This emphasis implies that anyone in Rwanda at the time of the genocide is tainted by the violence. Only those who lost their lives opposing the genocide can be known to have truly challenged the violence. Survival implies cooption; one has to have done something to survive. Hence, not only all Hutu who survived are suspect, even if they seemed to actively oppose the genocide, but also by implication, so are Tutsi survivors.Footnote 84

The narrative attributes the genocide to sources both external and internal to Rwanda. International responsibility for the genocide is assigned not simply to the role that colonialism played in creating ethnic divisions, but also to ongoing failures by the international community.Footnote 85 France is singled out in particular for having supported the Habyarimana regime, cooperated with the FAR in combating the RPF, trained and armed the militia groups that carried out the genocide, and helped the Rwandan army and militia members escape into Zaire by establishing the Zone Turquoise.Footnote 86 Kagame writes, “I hold the French government, in particular, responsible for helping to arm and train the militias that dispersed throughout the country to wipe out the Tutsi population.”Footnote 87 The rest of the international community bears responsibility for failing to stop the genocide. Kagame asserted, “The UN and the international community as a whole abandoned Rwanda in 1994.”Footnote 88 Gasana Ndoba, the president of the National Commission for Human Rights, asserted that, “the genocide was prepared and executed in the view of and with the knowledge of the international community.”Footnote 89 In his speech on the ninth anniversary of the genocide, President Kagame, asked, “Fifty years ago they said, ‘Never again,’ but what did they do so that this would not be committed in our country?”Footnote 90

The narrative attributes blame within the country in two distinct ways. Responsibility lies first with the elite, particularly government officials, who selfishly used their power for personal gain and served foreign interests rather than the national interest. Bad governance is a common theme in discussions of the genocide. The leaders of both the First and Second Republics are regarded as having set the stage for the genocide with their abuse of power and their ethnic discrimination. The discourse pays scant attention to the internal process of democratization from 1990 to 1994 other than to note that many politicians formerly in opposition ultimately re-aligned themselves with President Habyarimana and the Hutu-Power movement. The Democratic Republican Movement (Mouvement Démocratique Républicain, MDR) is particularly singled out for having maintained the anti-Tutsi values of its predecessor party Parmehutu.Footnote 91 A few Hutu, such as Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, are recognized as martyrs, but the narrative sees most Hutu as having in fact been complicit in the genocide.

Elites outside the government are also condemned for their complicity. Members of civil society – even human rights organizations – are said to have participated in the genocide, indicating the total bankruptcy of the intellectual class. Paul Rutayisire makes a stinging critique of the Catholic Church and its complicity in the genocide, both for its historic and contemporary role, a perspective embraced by many of the former refugee intellectuals. “In the process that led to genocide, the Catholic hierarchy was complicit, as much in its behavior as in its teachings, in broadcasting the evil that ate away at Rwandan society. Even the most unconditional defenders of the Catholic Church do not contest this fact.”Footnote 92 In general, the educated in Rwanda, whether in the government or outside, are considered to have led the country down the road to genocide.

The narrative walks a fine line between blaming the Rwandan population and vindicating them by blaming the international community and the national leadership. The masses are regarded as having participated widely in the genocide, but mostly because of their severe poverty and ignorance that made them vulnerable to manipulation by ill-intentioned elites. The masses were deceived by “an ideology of discrimination,”Footnote 93 that claimed not only that the Tutsi were foreigners and that Rwanda belonged to Hutu,Footnote 94 but that all Tutsi in Rwanda were enemies of the Hutu; killing Tutsi was therefore self-defense.Footnote 95 The low level of education within the population limited the masses’ capacity to critically assess the false ideas being fed to them.Footnote 96 Poverty is also considered a major cause of the genocide, as the wretched lives of the masses made them respond to promises of economic opportunity.

Given its centrality, the genocide must be highlighted and commemorated in order to prevent it from recurring. As the regional representative of the survivors’ group IBUKA reported in a radio interview, “Some people have even said that remembering [the genocide] does not coincide with the process of unity and reconciliation of Rwandans. This is not a good idea. People holding this opinion only take account of their own interests. … He who doesn’t know where he is coming from, doesn’t know where he is going.”Footnote 97

The RPF as Agent of Peace and Democracy

The narrative depicts the RPF as Rwanda’s saviors who reluctantly used military force for the benefit of all Rwandan people. Rwanda was suffering under dictatorship and violence, and the Habyarimana regime was unwilling to accept real democracy or allow refugees the right to return to their homeland. “The RPF had to develop an armed wing, because the Rwandan regime did not understand the language of peace.”Footnote 98 The goals of the RPF were the repatriation of refugees, the overthrow of the dictatorship, and the “elimination of the virus of divisionism.”Footnote 99

The narrative portrays the RPF as serving a noble cause and acting out of self-sacrifice, and their invasion is called the “War of Liberation.” The beginning of the war in 1990 is commemorated as a national holiday annually on October 1, known as the Day of Patriotism. In a speech marking the holiday in 2002, President Kagame claimed, “[T]welve years ago to the day, Rwandans began to struggle against injustice in Rwanda and to proceed with the general reform of the bad politics that scatter the Rwandan people. … This day … reminds us that Rwandans who love their country whether in the interior or the exterior rose up to struggle against the bad leadership that existed in the country.”Footnote 100 While the War of October, as it was known within Rwanda, was extremely unpopular within the country at the time, the RPF has attempted to use the Day of Patriotism to recast the war as a struggle not against the Rwandan people but by the Rwandan people against corrupt authoritarian governance and ethnic violence. Ignoring the pro-democracy movement that had begun months earlier, the narrative treats the RPF invasion as the beginning of efforts for reform.

The idea that the RPF stopped the genocide is a crucial element of the historical narrative. While the international community utterly failed to act on the promise of “never again,” the RPF acted boldly, renewing its attack on Rwanda with the sole purpose of stopping the genocide. According to Bernardin Muzungu, “While the machete and other instruments of death made the law in Rwanda and the international community waited with arms crossed, the RPF-Inkotanyi threw its youth into the fire. The dispersal of the killers was total.”Footnote 101 The attack on Rwanda that the RPF renewed in April 1994 is reinterpreted as an “anti-genocidal campaign.”Footnote 102

According to the narrative, the RPF has devoted itself since taking power to correcting the mistakes of the past and reforming Rwanda so that ethnic violence will never recur. As Kagame said, “When the RPF took over, Rwanda was in utter anarchy. … We quickly realized that our task was to restore hope to the Rwandan people and to return power to the population. We have restored trust in the judiciary and have therefore been able to avoid revenge. The long established culture of impunity, which made possible the 1994 genocide, has at last been broken. People now have complete security of life and property.”Footnote 103 The RPF fought against ethnic discrimination and “divisionism,” establishing a multi-party, multi-ethnic “government of transition.”Footnote 104 The mention of ethnicity was removed from national identity cards, and positions in schools and government employment are now determined by the principle of merit. Many articles on the history of ethnic violence include a statement on how the current regime has broken with the practice of discrimination. For example, Kayihura writes, “Today, four years after the genocide, the Government of National Unity is striving, against winds and tides, to restore the Rwandan society in a context of beneficial national reconciliation.”Footnote 105

A corollary of the narrative depicting the RPF as noble and self-sacrificing seeks to obliterate any public memory of RPF abuses during and after the 1990–1994 war. As heroic saviors of the country, the RPF cannot also be villains. The idea that the RPF bears any responsibility for the genocide itself, for having attacked the country without regard for the consequences for Tutsi still within Rwanda, is categorically rejected.Footnote 106 Furthermore, any apparent abuses during the war and its aftermath are either unfortunate casualties of a just war (generally seen as misunderstood or exaggerated) or the actions of rogue individuals who operated outside the approval of the RPF leadership. As Kagame said, “We acted to stop a genocide, but you cannot stop individuals from committing crimes individually.”Footnote 107 His point is that any violence carried out against civilians by the RPF or its soldiers was incidental and not systematic. The idea of a “double genocide” advanced by some regime critics is vociferously rejected as a form of genocide denial; if both sides committed genocide, then blame is shared and the crime is less serious. As Kagame said in response to a question about potential indictments of RPF officials at the ICTR, “What in Rwanda we are opposed to is equating inequitable situations. … Don’t divert from the main purpose of the Tribunal, and that is to try those involved in the genocide.”Footnote 108 Rwanda’s two incursions into the DRC in 1996–1997 and 1998–2002 were necessary for Rwanda’s security, particularly to prevent a recurrence of genocide. The troops “showed their courage and their sacrifice based on their patriotic love [of Rwanda]”Footnote 109

Criticism of the RPF is treated as revisionist support for the “double genocide” theory. An article on the double-genocide theory equates criticism of the RPF with both genocide denial and support for the génocidaires.Footnote 110 Those in the international community who criticize the RPF regime are hypocrites, since they did not oppose the regime that carried out the genocide but now dare to condemn the RPF, which stopped the genocide.Footnote 111 Those Rwandans who criticize the RPF demonstrate their continuing adherence to genocidal ideologies. For example, when former President Bizimungu’s political party was banned for promoting “divisionism,” those who supported the new political party that he formed were accused of supporting genocide.Footnote 112 A few months later, the MDR was similarly criticized for having, “always supported the divisions that have beset our country,”Footnote 113 and its presidential candidate, former Prime Minister Twagiramungu was accused of having denied the genocide.Footnote 114 The parliamentary committee ultimately concluded that the MDR should be suppressed, because the ideology of the party was merely a continuation of Kayibanda’s anti-Tutsi Parmehutu and the leadership was both implicated in the genocide and continued to support a genocidal ideology.Footnote 115 Critics of the regime are also commonly accused of putting their own interests first and indulging in corruption. As one governor declared in a public meeting, “The ethnic divisions that have characterized Rwanda are hidden behind people who would simply fill their stomachs – for selfish interests.”Footnote 116 In short, the RPF has the best interests of the country in mind, and those who would criticize the party and government hold only selfish interests and have yet to give up the divisive racist thinking of the past.

President Kagame’s forward to a book on transitional justice in Rwanda amply demonstrates the various points about the RPF that I have outlined here:

A new phenomenon has emerged in the form of individuals and groups who seek to revise history for their own gain, including many who deny outright that genocide took place in Rwanda in 1994. These revisionists, including Rwandan and non-Rwandan ideologues, academics, journalists and political leaders, now claim that the genocide was a myth; that what occurred in 1994 was simply a civil war between two equal sides or the spontaneous flaring of ancient tribal hatred. Even worse, some of these sources accuse the RPF, the force that halted the genocide, of seeking to exterminate the Hutu population. This is an absolute falsehood, sheer nonsense. While some rogue RPF elements committed crimes against civilians during the civil war after 1990, and during the anti-genocidal campaign, individuals were punished severely according to the RPF’s internal procedures of the day. To try to construct a case of moral equivalency between genocide crimes and isolated crimes committed by rogue RPF members is morally bankrupt and an insult to all Rwandans, especially survivors of the genocide. Objective history illustrates the bankruptcy of this emerging revisionism. The fact that there was no mass revenge in the post-genocide period – which could have easily occurred – is evidence of the clarity of purpose of the Rwandan leadership that actively mobilized the Rwandan population for higher moral purposes than the revisionists contend.Footnote 117

The Official Narrative and Constraints on Historical Debate

I have attempted above to provide as accurate as possible a summation of the official historical narrative advanced by the RPF and its supporters with little commentary.Footnote 118 My goal in this chapter is not to assess the accuracy of the historical discourse but rather to understand its main points in order to appreciate the major themes of the collective memory that the RPF has sought to promote. In fact, many of the points in the current official narrative diverge from or directly contradict the conclusions of most historians and other scholars outside Rwanda. The need to emphasize unity and reject the significance of ethnicity has led to distortions of historical reality. The narrative exaggerates the unifying role of the monarchy by denying the fluid nature of political boundaries in pre-colonial Rwanda, ignoring both the presence of autonomous Hutu kingdoms within the territory and the tenuous ties of peripheral areas to the central court. Placing the genocide at the center of Rwandan history treats the past hundred years as a linear progression toward that signal event, ignoring much of the actual complexity of events in both the colonial and post-colonial eras. The official interpretation of the genocide conceals the facilitating role of the RPF invasion and ignores atrocities committed by the RPF itself.

In promoting a singular narrative, Rwanda’s new elite seeks to develop a unified collective memory for the Rwandan population, one they hope not only creates a propitious environment for their continuing social, economic, and political dominance but will also ultimately reshape what it means to be Rwandan in a way that will prevent future ethnic violence. If, as I have argued, the belief in distinct historical origins made the genocide possible by delineating Hutu from Tutsi and Twa, then developing a belief in a unified history, it is hoped, will eliminate the basis for inter-group violence. Whatever their merits, the distinctly political goals of the effort to rewrite history leave little room for dissention and debate.

In the project that I helped direct to develop modules for a history curriculum for Rwandan secondary schools, we sought to encourage an alternative method of approaching history as a set of questions and problems rather than a list of facts.Footnote 119 In the course of this project, however, my American colleagues and I witnessed exactly how the official narrative serves to constrain discussions of history even among trained historians. Two small incidents serve as examples. The first involves the choice of focus for the working group on pre-colonial Rwanda. David Newbury, a prominent historian of Rwanda, participated in the project as a consultant and advised the pre-colonial group. Newbury has written extensively on clans, and in a definitive work on the topic published in 1980, he argued that clans were not, as earlier histories had maintained, the most important social identifier in pre-colonial Rwanda. While clans were significant for the organization of power in the central court, for most people in what is today Rwanda they were less significant as social identifiers than region and lineage. In fact, the expansion of the clan structure throughout Rwanda was actually part of the process of the extension of central control by the monarchy.Footnote 120

The official post-genocide narrative, however, has treated clans as a central aspect of Rwandan history. The fact that clans in Rwanda are multi-ethnic, most including all three groups, is used in the official narrative to support the ideas that the Rwandan people were historically unified and that ethnicity was an artificial creation of the colonial state. Furthermore, clans were important to competitions for power in the Rwandan royal court, even into the colonial period. Tutsi who fled Rwanda beginning in 1959 came disproportionately from the political elite, and in exile, particularly in Uganda, clan identity remained important to them. Inside Rwanda, clans diminished even further in importance, serving little purpose other than limiting marital choices (since Rwandans marry outside their clans). The refugees who returned to Rwanda beginning in 1994 brought with them the perspective that clans were central to Rwandan society. (President Kagame is from the clan of the queen mother, the Abega, and many people have said that his rise to power represents the final victory of the Abega over the Nyiginya clan.) Thus, despite the advice from the pre-eminent expert on clans in Rwanda that the pre-colonial working group focus on a topic less distorted by ideology, the pre-colonial group insisted on choosing clans as their focus and presented clans in a fashion consistent with the official narrative – though they did include a few references to the work of Newbury to indicate that there were divergent perspectives.

Another example from our project of how politicized history has become in Rwanda involved the working group charged with treating the post-independence period. The group included in the initial draft of their materials a section that sought to implicate one of Rwanda’s most respected Hutu human rights activists, Father André Sibomana, in a notorious case of anti-Tutsi discrimination in the late-1980s, the “Muvara Affair.” In 1988, the Vatican appointed as bishop Father Félicièn Muvara, a Tutsi priest, but just days before his installation, he withdrew, claiming “personal reasons.” In fact, rumors quickly spread that he had been pressured to withdraw by leaders in both the government and the church after a “whispering campaign” falsely accused him of fathering a child out of wedlock.Footnote 121 The materials presented by the post-independence group asserted that Sibomana had instigated the rumors against Muvara.

I strongly believe that the accusations against Sibomana were driven not by the actual events related to Muvara but rather by a contemporary attempt to discredit Sibomana in the post-genocide context. I personally knew both Muvara and Sibomana and researched the Muvara affair during the period just prior to the genocide. Muvara was the curé of one of the Catholic parishes where I conducted research in 1992–1993, and I interviewed him several times, including an extended interview focused specifically on his abandoned appointment as bishop. The evidence that he and others provided me painted a very different picture that directly implicated the archbishop, a close ally of President Haybarimana.