21 - Bernstein’s Endgame, 1989–1990

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 April 2021

Summary

LEONARD BERNSTEIN DIED on October 14th 1990. Twenty years earlier he changed the course of my life by signing me up to direct films and videos of his concerts. From the start we also filmed documentaries which threw light on the music he was conducting. In the 1980s I persuaded him to widen the field by getting involved in autobiographical essays, although the first of these was actually his own whim – and LB had a whim of iron: his notion was nothing less than a session on Dr Freud's famous consulting couch, agonising as to why a good Jewish boy such as himself should be conducting the music of the grossly anti-Semitic Richard Wagner.

In 1985 LB was in Vienna because, as a quid pro quo for the Staatsoper's decision to mount his own opera A Quiet Place the following season, he had agreed to conduct a concert performance of the second act of Die Walküre on stage at the Vienna State Opera. LB had long been aware of Viennese anti-Semitism – on his first visit as a maestro, in 1966, he walked up and down the city's main street, the Kartnerstrasse, asking passers-by for directions to Mahlergasse, Mahler Street, knowing full well that the city had still not reinstated the street name that had been stripped away by the Nazis, because Mahler was a Jew, after the Anschluss in 1938. He loved conducting Wagner – indeed, had recently recorded a complete Tristan in Munich – but naturally, being Jewish, he felt uneasy about enjoying the music of such a rabid Jew-hater. His response was to propose that since he was in the cradle of psychoanalysis he should undertake a session in the most famous consulting room in Europe at Berggasse 19 in the Ninth district, the home for forty-seven years of Dr Sigmund Freud.

I was not free to direct the filming – I suspect for diplomatic reasons – so my regular Unitel producer Horant Hohlfeld took charge of the shoot. Lenny reclined on what was said to be the authentic couch (the Freud Museum in London boasts another) and poured out his soul to the camera.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

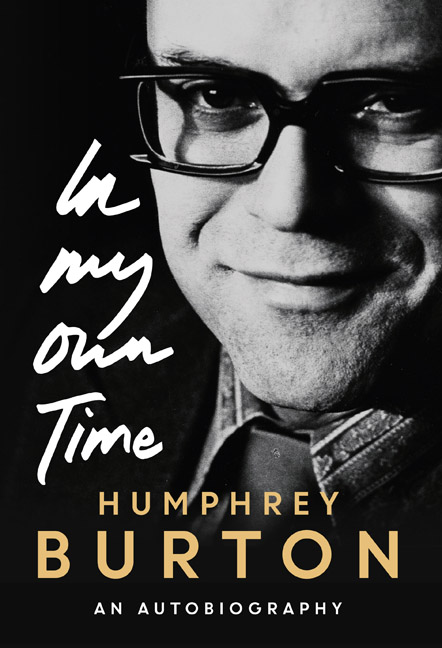

- Humphrey Burton In My Own TimeAn Autobiography, pp. 441 - 456Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021