Book contents

- A Handbook of Primary Commodities in the Global Economy

- A Handbook of Primary Commodities in the Global Economy

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Historical Framework

- 2 The Geography of Commodity Production and Trade

- 3 Comparative Advantage and Trade Policy Distortions

- 4 Fossil Fuels

- 5 Price Formation and Price Trends in Commodities

- 6 Commodity Booms

- 7 Commodity Exchanges, Commodity Investments and Speculation

- 8 Sustainability and the Threats of Resource Depletion

- 9 Fears of and Measures to Assure Supply Security

- 10 Producer Cartels in International Commodity Markets

- 11 Public Ownership of Commodity Production

- 12 The Monoeconomies: Issues Raised by Heavy Dependence on Commodity Production and Exports

- References

- Index

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 November 2020

- A Handbook of Primary Commodities in the Global Economy

- A Handbook of Primary Commodities in the Global Economy

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Historical Framework

- 2 The Geography of Commodity Production and Trade

- 3 Comparative Advantage and Trade Policy Distortions

- 4 Fossil Fuels

- 5 Price Formation and Price Trends in Commodities

- 6 Commodity Booms

- 7 Commodity Exchanges, Commodity Investments and Speculation

- 8 Sustainability and the Threats of Resource Depletion

- 9 Fears of and Measures to Assure Supply Security

- 10 Producer Cartels in International Commodity Markets

- 11 Public Ownership of Commodity Production

- 12 The Monoeconomies: Issues Raised by Heavy Dependence on Commodity Production and Exports

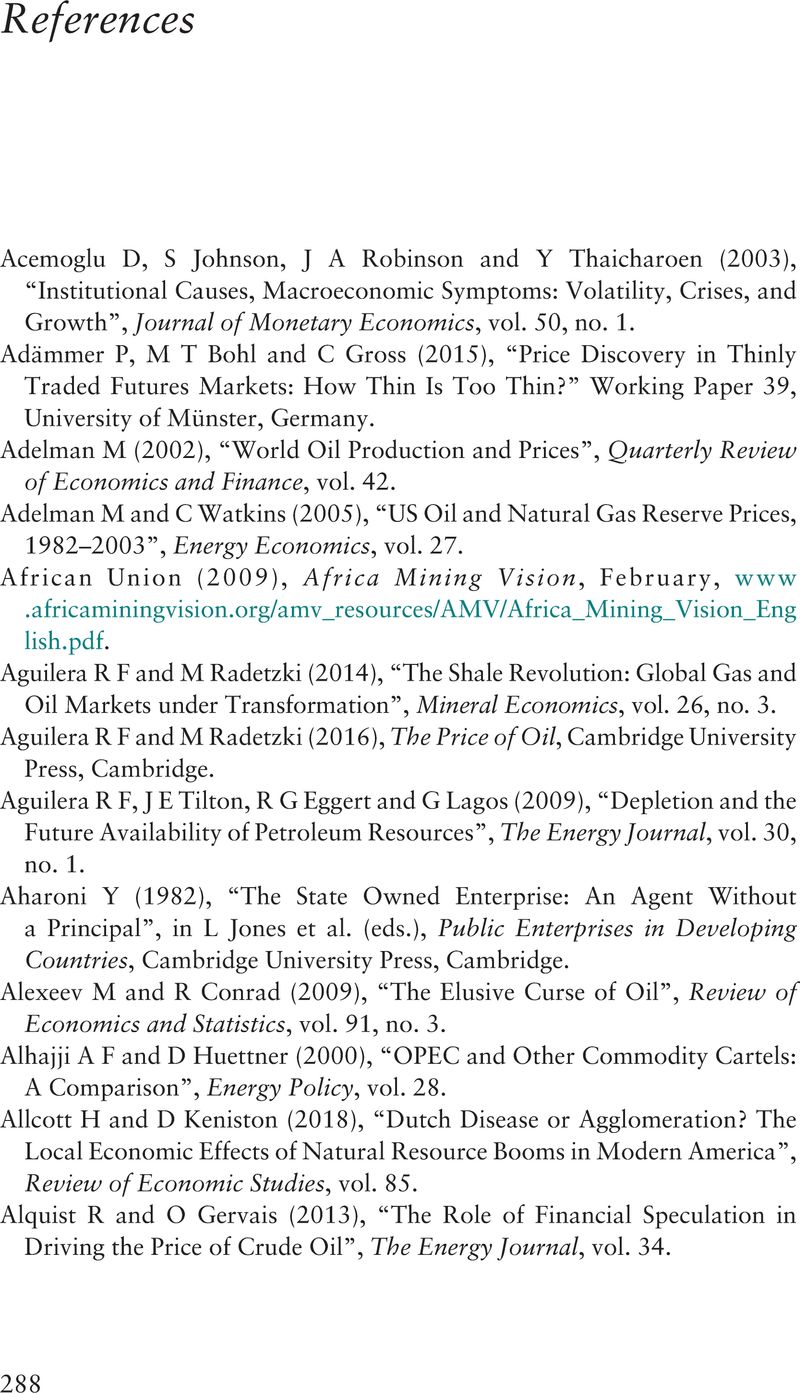

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Handbook of Primary Commodities in the Global Economy , pp. 288 - 307Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020