7.1 Introduction

This chapter builds on the insights of the previous chapters about the institutional complexity of the climate-energy nexus. As was shown in Chapter 3, the global institutional complex on climate and energy governance has in recent years developed into a crowded field with the emergence of several international institutions that seek to address both issues in tandem. Hence, multiple actors work in the same area without overarching coordination (Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Pattberg, van Asselt and Zelli2009). With different mandates, forms, functions, and values, these institutions both cooperate and compete with one another to further their mission. Given scarce resources amongst policy makers and other stakeholders, these actors need to prioritize which institutions to engage with.

Central to the question of which international institutions warrant support and are prioritized are considerations of the institutions’ legitimacy. With competition over members and resources, international institutions depend on favourable perceptions of legitimacy by a diverse set of global governance stakeholders, such as policy makers, nongovernmental organizations, and businesses, to achieve their objectives (Andresen and Hey Reference Andresen and Hey2005; Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Pattberg, van Asselt and Zelli2009). As was discussed in Chapter 2, legitimacy broadly refers to ‘the acceptance and justification of shared rule by a community’ (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2005, 142). Legitimacy is important for international institutions in order to be able to operate with authority and to attract constructive participation of political and societal stakeholders in the processes of making and implementing governance. Put differently, to achieve their objectives, international institutions must gain acceptance, trust, and credibility amongst the communities that they seek to govern (Andresen and Hey Reference Andresen and Hey2005).

The aim of this chapter is to understand how international institutions operating under institutional complexity are perceived by key stakeholders in terms of legitimacy. We present a novel approach to studying legitimacy perceptions as we capture stakeholders’ assessments of a broad range of dimensions of legitimacy and bring those together in a composite measure of legitimacy assessments. Scholarly work on the concept of legitimacy highlights, and debates, that legitimacy is built on institutional qualities such as how the internal decision-making and accountability structures work and how effective and fair the institution is perceived to be (Scholte and Tallberg Reference Scholte, Tallberg, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018). We contribute to this debate by showing that the surveyed stakeholders in climate and energy governance indeed perceive these elements as dimensions of the broader concept of legitimacy.

Concretely, by focusing on those aspects of legitimacy that international institutions themselves can influence, i.e. their institutional qualities, we contribute to understanding how perceptions of these – i.e. what we call legitimacy assessments – differ between stakeholder groups. Previous literature has to our knowledge not mapped stakeholder’s perceptions of a set of institutions that work on similar issues and that thereby have overlapping mandates. In terms of empirical novelty, the chapter offers a systematic and comparative mapping of stakeholders’ legitimacy assessments of five institutions. To this end, it uses a hybrid approach focusing on stakeholders’ assessments of those dimensions of legitimacy that concern institutional qualities. Theoretically, the chapter unpacks the meaning of legitimacy under institutional complexity.

This chapter thereby provides innovative insights to the literatures on both legitimacy and institutional complexity, with implications for ways in which climate and energy governance can be strengthened. Moreover, the findings have implications for how institutions may influence perceived legitimacy deficits through legitimation strategies toward different stakeholder audiences (Bäckstrand and Söderbaum Reference Bäckstrand, Söderbaum, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018).

We gained insight into stakeholders’ legitimacy assessments by fielding an expert survey among energy and climate stakeholders from different world regions. Respondents were asked about five climate and energy governance institutions that exhibit different but overlapping mandates and membership: the Clean Energy Ministerial (CEM), the International Energy Agency (IEA), the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN 21), and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). All five institutions belong to the subfield of renewable energy. As shown in Chapter 4, they play a key role for this subfield. Based on that chapter and its analysis of institutional coherence and management on renewable energy, we now expand the analysis of this subfield toward institutional legitimacy. The stakeholders who evaluate the five selected institutions comprise both state and nonstate actors, work with different issues (e.g. mitigation, adaptation, energy security, climate finance, and technology) and come from varying regions of the world. The data allow us to show how legitimacy assessments of these five institutions differ across stakeholder types and across stakeholders working with different issues.

The chapter proceeds as follows. The next section presents our framework for studying stakeholders’ legitimacy assessments. Here, we also further develop the conceptual insights on legitimacy introduced in Chapter 2. Next, the five institutions in climate and energy governance are described, paying specific attention to the institutional qualities that are expected to be relevant in guiding legitimacy assessments. Thereafter, the data and methods section outlines how we measured these assessments. The results section then maps stakeholders’ legitimacy assessments of the five institutions in our study. The final section summarizes the insights gained and highlights avenues for further research.

7.2 Theory and Concepts

As argued in Chapter 2, institutional complexity complicates an evaluation of legitimacy of individual institutions because of the interlinkages and overlapping mandates between institutions. In this section, we link back to the discussion in Chapter 2 on the concept of legitimacy and highlight how the cognitive model of legitimacy provides insights into understanding legitimacy under institutional complexity. Thereafter, we discuss the institutional qualities that have been argued to be central to institutions’ legitimacy, deriving nine dimensions of legitimacy.

7.2.1 Congruence and Cognition: Understanding Perceptions of Legitimacy

The traditional view of legitimacy in IR has held that ‘legitimacy depends on the congruence between an organization’s features – specifically, its procedures, purpose, and performance – on the one hand, and the inter-subjectively shared norms and values held by relevant organizational stakeholders, on the other hand’ (Lenz and Viola Reference Lenz and Viola2017, 943). Legitimacy in this view depends on the extent to which an institution lives up to certain legitimacy demands that stakeholders have, which are determined by the norms and values of those stakeholders. Recent research by Lenz and Viola (Reference Lenz and Viola2017) has, however, outlined several empirical and analytical weaknesses in the traditional approach – or what they call ‘the congruence model of legitimacy’. Central to this argument are limitations to stakeholders’ ability to make a precise and complete evaluation of an institution in order to compare this to their normative beliefs.

Instead, Lenz and Viola (Reference Lenz and Viola2017) introduce a ‘cognitive model’ for understanding how legitimacy perceptions are formed. This model draws on the literature on cognitive psychology to outline the micro-foundations for understanding the formation of legitimacy perceptions and reflects similar approaches in the public opinion literature (Armingeon and Ceka Reference Armingeon and Ceka2014). The three core insights that inform their model are: ‘(1) judgments rely on cognitive schemata and heuristics that bias judgments; (2) they are comparative; and (3) they are sticky, up to a threshold’ (Lenz and Viola Reference Lenz and Viola2017, 947–948).

According to these insights, legitimacy perceptions are not formed in a vacuum, i.e. actors do not judge institutions one by one against their held social values and norms. Rather, perceptions of an institution are based on a reference point that is derived from previous experiences. These heuristics consist of perceptions of institutions that stakeholders are most familiar with or which they most recently engaged with, but it may also consist of an ideational prototype of what the perfect institution would look like. Heuristics are presented as rather stable images in stakeholders’ minds. When we ask stakeholders to assess the legitimacy of an institution, we should therefore expect them to compare the perceived qualities of that institution to those of their ‘heuristic’ institution. Moreover, we can expect variations across stakeholders as they will have different reference points, or heuristics, depending on their background, the institutions they are mostly familiar with, and the norms they hold.

While this turns legitimacy assessments into something much more personal than the congruence model proposes, processes of socialization and shared experiences within specific professional sectors lead us to expect systematic similarities in the used heuristics and normative beliefs about legitimacy across individuals within the same sector, and differences among individuals in different sectors. For instance, nonstate actors such as business or civil society actors may assess institutions in relation to the norms of legitimate governance that are central in their respective peer group. Likewise, climate- and energy-related stakeholders that also work on questions of international development are expected to keep development institutions, and their respective norms, in mind when they assess the legitimacy of the climate and energy governance institutions in our study. This very use of heuristics, as well as its dependence upon stakeholders’ specific experiences, provides an additional motivation for studying individual legitimacy assessments (Scholte and Tallberg Reference Scholte, Tallberg, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018).

This conception of legitimacy has two key implications for how we can understand legitimacy perceptions. First, this chapter argues that an awareness of cognitive limitations is central to understanding legitimacy beliefs. Rather than assuming that actors, even if they are experts, are capable of capturing the exact way in which institutions function and the extent to which the institution is in line with those actors’ normative beliefs, one should recognize that legitimacy assessments are based on heuristics and underlying experiences, which come with respective limitations. Especially in a highly complex, and therefore cognitively demanding, institutional environment, one may expect actors to base their legitimacy assessments on such heuristic simplifications. When facing several institutions with overlapping and complex mandates, actors may use mental shortcuts to form opinions about some of these institutions (Alter and Meunier Reference Alter and Meunier2009).

Second, the norms, values, and experience of actors can both influence how they assess the qualities of an institution as well as how they value these qualities, i.e. the relative importance that they place on the purpose, process, or performance of institutions. In other words, stakeholders’ legitimacy perceptions may differ either because they assess the institutional qualities of institutions differently, and/or because they value different characteristics of legitimacy differently. This means that an actor’s legitimacy perceptions, i.e. the extent to which an institution is viewed as legitimate by an actor, is a combination of that actor’s legitimacy assessment (i.e. an assessment of the institutional qualities of an institution) and that actor’s legitimacy valuation (i.e. the importance attached to certain institutional qualities). This chapter focuses on legitimacy assessments by climate and energy experts along nine dimensions of legitimacy as explained in the next section.

7.2.2 Legitimacy Criteria Used to Map Perceptions

Legitimacy is the assessment and valuation by an audience as to the appropriateness of an authority. What should be considered a legitimate form of authority has preoccupied normative scholars. What is in practice considered a legitimate form of authority is instead the focus of sociological work (Nasiritousi et al. Reference Nasiritousi, Hjerpe and Bäckstrand2016). In this chapter we opt for a hybrid approach, as we study stakeholders’ perceptions of institutions while referring to normative criteria of legitimate governance (cf. Agné Reference Agné, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018). This take thus differs from a ‘purely’ sociological approach where it is left to selected stakeholders to determine relevant criteria for assessing an institutions’ legitimacy. In this type of study, legitimacy is empirically measured as confidence in, or support for, an institution (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira1998; Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015).

The current study, in contrast, combines normative and sociological aspects. It does so by seeking to understand legitimacy in terms of its different dimensions. This approach provides a uniquely fine-grained perspective on legitimacy perceptions (cf. Scholte and Tallberg Reference Scholte, Tallberg, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018). The hybrid approach is in line with the work of Beetham (Reference Beetham1991), who argues that legitimacy has both a normative and sociological component, as perceptions of institutions’ legitimacy will be based on institutions meeting normative criteria on the exercise of power.

Concretely we seek to provide a comparative mapping of stakeholders’ views of a set of nine institutional qualities or dimensions derived from the normative literature. This helps us to better understand how legitimacy assessments may vary between different institutions and various stakeholder groups. These assessments are expected to be an important indicator for sociological legitimacy (cf. Scholte and Tallberg Reference Scholte, Tallberg, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018).

Our conceptual framework therefore begins with identifying dimensions of legitimacy. We do so by advancing normative criteria, i.e. a set of standards that are ‘grounded in normative theories that reflect prevailing sociological standards in society’ (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee2013, 58). Central to the identification of dimensions of legitimacy is the distinction between input and output legitimacy. While input legitimacy refers to the design of political processes, i.e. governance by the people, output legitimacy concerns problem-solving capacity, i.e. governance for the people (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999). By exploring aspects of input and output legitimacy, it is possible to derive criteria for assessing legitimacy anchored in a normative framework.

The normative framework presented in Table 7.1 builds on the works of Bodansky (Reference Bodansky1999), Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and Vihma (Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and Vihma2009) and Mena and Palazzo (Reference Mena and Palazzo2012). The framework distinguishes source-based and process-based input legitimacy, as well as substantial and distributive output legitimacy. These unfold into a total of nine dimensions of legitimacy.

Table 7.1 Analytical Framework - Dimensions of Input and Output Legitimacy and their Operationalization.

| Input or Output Legitimacy | Dimensions of Legitimacy | Operationalization in Survey |

|---|---|---|

| For those institutions in Question 6 that you are familiar with (where you answered 3–5), please evaluate these institutions in their respective column according to the criteria below. Write a score between 1–5 in each cell, where 1 means that the institution is very weak and 5 means it is very strong on the respective dimension. | ||

| Source-based (input) legitimacy | Source of authority | Expertise |

| Process-based (input) legitimacy | Inclusion | Inclusion of all appropriate actors |

| Procedural fairness | Procedural (decision-making) fairness | |

| Transparency | Transparency | |

| Accountability | Accountability | |

| Substantial (output) legitimacy | Output | Output (what is produced) |

| Outcome | Outcome (the effect the output has on its members) | |

| Impact | Impact (the effect the output has on problem-solving) | |

| Distributive (output) legitimacy | Distributive fairness | Distributive fairness (distributing benefits to members fairly) |

Source-based legitimacy refers to how authority is gained by an institution – not by its operations, but through its essence and standing. Three common forms of source-based legitimacy are expertise, tradition, and discourse (Karlsson-Vinkuyzen and McGee Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee2013). Process-based legitimacy pertains to the design of procedural rules that affect the decision making of the institution. Inclusion refers to how open the institution is in terms of membership. Procedural fairness in decision making means that stakeholders have opportunities to be heard and be treated fairly so as to have a sense of ownership of the decisions made (Raines Reference Raines2003). Transparency relates to the degree of access to information that the institution provides to members and other stakeholders. Accountability implies that institutions can be held to account for the decisions that they make and for the ways in which they implement these decisions. Substantial legitimacy is concerned with issues of effectiveness. Output concerns performance in terms of what the international institution produces, for example issuing regulations (these can be binding or non-binding), producing reports, conducting research, organizing meetings, providing funding, providing training, etc. (Szulecki et al. Reference Szulecki, Pattberg and Biermann2011). Outcome relates to whether the institution produces behavioural changes, for example in terms of whether the institution increases the level of cooperation and compliance amongst members for instance by improving learning and modifying incentives (Underdal Reference Underdal, Miles, Underdal, Andresen, Wettestad, Skjærseth and Carlin2002; Gutner and Thompson Reference Gutner and Thompson2010). To determine an institution’s impact involves making judgements about the extent to which the institution contributes to alleviating the problem it was tasked to resolve (Underdal Reference Underdal, Miles, Underdal, Andresen, Wettestad, Skjærseth and Carlin2002). Distributive legitimacy, finally, is a dimension that is concerned with the distribution of benefits to the members of the institution.

7.3 The Five Cases: Similarities and Differences in Institutional Qualities

The five institutions whose legitimacy we put under scrutiny in this chapter are: CEM, IEA, IRENA, REN21, and UNFCCC. These institutions have different forms and functions, yet they also have overlapping mandates. We selected these institutions since they pertain to one major subfield of the climate-energy nexus, namely renewable energy. Chapter 4 analyzed the degree of coherence of the renewable energy subfield and identified these as the key institutions therein (Sanderink, this volume). Their importance was further confirmed by climate and energy experts (both state and nonstate actors) that we interviewed prior to designing our questionnaire. The five institutions have thus all achieved a certain level of authority, which makes them interesting cases for a comparative mapping of how stakeholders’ legitimacy assessments differ amongst these key institutions. In what follows, we briefly introduce the five institutions based on their self-descriptions – by representatives we approached or on their websitesFootnote 1 – and highlight a number of similarities and differences across them in terms of key properties. The descriptions form the context for our expectations that we thereafter derive about how stakeholders make legitimacy assessments.

The most long-standing institution in our sample is the IEA – an intergovernmental organization that was established in 1974 and is based in Paris. The IEA was established within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in response to the 1973 oil crisis to strengthen the cooperation of industrialized countries to meet the energy needs of oil-consuming countries. The agency draws its thirty member countries from the OECD group of industrialized countries, and, in addition, features eight association countries: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Singapore, South Africa, and Thailand (IEA 2018a). Association countries may participate in the analytical work of the IEA, but have no rights and obligations. While its main focus has been to tackle global oil supply disruptions, the IEA’s mandate has broadened to ‘ensure reliable, affordable and clean energy for its thirty member countries and beyond’ (IEA 2018b). It has a global scope and works on energy security, sustainability and clean energy transitions, technology, innovation, and energy access. The main decision-making body of the IEA is the Governing Board, which comprises energy ministers or their senior representatives from each member country. Governing Board decisions are legally binding on all member countries. Majority vote is based on a system of voting weights allocated to each member country. Such a vote is required for decisions on the IEA Programme of Work, procedural questions, and recommendations. Unanimity is required for other decisions. The IEA works closely with partners, including industry partners, and other international institutions to gain insights and advice from outside actors (IEA 2018c). There is no formal role for nonstate actors, but nonstate actors may contribute to and peer-review IEA reports, participate in IEA events and programmes, and serve on IEA advisory boards. In terms of output, the IEA collects data, conducts research, provides analysis, makes policy recommendations, produces reports, organizes meetings/workshops/seminars, and offers training.

Almost two decades after the establishment of the IEA, countries adopted the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992. With near-universal membership, the objective of the UNFCCC is to ‘stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’ (UNFCCC 2018). Tasked with supporting the operation of this international environmental treaty, the UNFCCC Secretariat is based in Bonn. The UNFCCC is an intergovernmental institution that makes decisions based on consensus. The UNFCCC deals with a range of issues related to climate change, including mitigation, adaptation, technology, capacity building, and finance. It is also one of the most open international institutions in terms of involving a range of nonstate actors in the yearly conferences compared to other institutions in, for example, trade or security fields (Nasiritousi and Linnér Reference Nasiritousi and Linnér2016). Nonstate actors also have a prominent role in the Global Action Agenda, an initiative to spur more ambitious climate action amongst stakeholders, as evidenced by the Yearbook for Global Climate Action (UN Climate Change Secretariat 2018) and the NAZCA database of climate commitments by nonstate actors. The UNFCCC’s key outputs have been the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2015 Paris Agreement, both landmark international agreements aimed at addressing the causes and consequences of climate change.

More recent institutions are REN21, IRENA, and CEM. REN21 was launched in 2004 as a ‘global renewable energy policy multi-stakeholder network’ (REN21 2018a). It is based at the office of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in Paris. Its mission is to facilitate knowledge exchange and drive a transition toward renewable energy. The members of REN21 come from five stakeholder groups: governments, industry associations, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academia, and other international organizations. REN21 tries to keep membership balanced between the five stakeholder groups. By implication, governments are outnumbered by nonstate actors. Government representatives come from the following thirteen countries: Afghanistan, Brazil, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Germany, India, Mexico, Norway, Republic of Korea, South Africa, Spain, United Arab Emirates, and the United States (REN21 2020). REN21 is thus a collaborative network that seeks to connect the public and private sectors on renewable energy (REN21 2018b). The Steering Committee is elected from REN21’s members, ten from each stakeholder group. From that, the seven people of the Bureau are elected. These elections are held at the annual meeting, the General Assembly, and this is the only time REN21 takes decisions by majority vote. Other decisions are typically consensus based. The Bureau provides month-to-month oversight while the Steering Committee conducts the broader, programmatic oversight. REN21’s key output is the annual Global Status Report, which presents a rich set of data on the status of renewables and is widely disseminated among actors in the field.

Founded in 2009, IRENA is an intergovernmental organization that is headquartered in Abu Dhabi. It currently has 161 member states, with further 22 states currently undergoing accession processes (IRENA 2020a). The agency seeks to promote adoption and sustainable use of all forms of renewable energy, in the pursuit of sustainable development, energy access, energy security and low-carbon economic growth. The main decision-making body of IRENA is the Assembly, which includes one representative from each member country. All matters of substance are decided by consensus among the members present, whereas questions of procedure are decided by simple majority. IRENA works with the broader renewable energy community, including companies, NGOs, and other international organizations, to facilitate knowledge-sharing (IRENA 2020b). Examples include a joint project facility, online info and marketplace platforms, initiatives, and the Coalition for Action (IRENA 2020c). In terms of output, IRENA is involved in many activities, including: research and publication of reports, providing member states and nonstate actors with recommendations, issuing non-binding regulations, and providing training and funding to support implementation.

Established in 2009, CEM is a high-level ministerial forum that seeks to advance clean energy technologies by promoting initiatives based on common interests among its members and other stakeholders. Its Secretariat is seated at the IEA headquarters in Paris. CEM members include twenty-seven country governments, but also the European Commission. It is the only regular meeting of ministers focusing on clean energy. Rather than relying on consensus, CEM employs a ‘distributed leadership’ model whereby any government interested in furthering an idea on clean energy technology is encouraged to identify willing partners and proceed. The initiatives, which countries join based on their interests and capabilities, must include three or more CEM members, be endowed with resources, and offer a tangible work plan. CEM’s work is divided into three general work categories: (1) energy supply systems and integration, (2) energy demand, and (3) cross-cutting support. The latter includes, for example, initiatives such as Women in Clean Energy and the Clean Energy Solutions Centre (which provides policy toolkits). In terms of output, each initiative sets its own deliverables and objectives, depending on their goals. Some produce reports and analysis, others focus on policy solutions, yet others use workshops, seminars, webinars, and other forms of knowledge-sharing. CEM also seeks the input of key private sector partners through, for instance, dedicated actions, commitments, or the hosting of workshops (CEM 2018).

These five institutions thus all operate in the complex of institutions that govern the climate-energy nexus within the subfield of renewable energy, but differ in a number of respects that may impact on how stakeholders assess their legitimacy. The first is in membership, where some are intergovernmental organizations with near-universal membership (UNFCCC, IRENA) while others are minilateral institutions (IEA and CEM) or multi-stakeholder partnerships (REN21). This may have implications for stakeholders’ assessments of their inclusion, procedural fairness, and distributive fairness. Second, they differ in terms of the scope of their mandate, where some have a broad mandate focusing on multiple issues (UNFCCC and IEA) whereas others concentrate on more specific questions (IRENA, REN21, and CEM). Third, they vary in terms of the nature of their mandate, with the UNFCCC having a political mandate requiring negotiations on contentious issues between countries, while the other four institutions in the sample are endowed with a more technical mandate focusing on implementation. Their mandate is likely to have implications for stakeholders’ assessments of the output, outcome, and impact of respective institutions. Fourth, the selected institutions differ with respect to how strongly they work with nonstate actors. The UNFCCC and REN21 have a close relationship with a broad range of nonstate actors in terms of access or cooperation. Other institutions are less engaged with such actors or are more selective, with a narrower set of nonstate collaboration partners (IRENA, CEM, IEA). This, in turn, may well affect stakeholders’ assessments of their levels of inclusion and expertise. Fifth and finally, most institutions take decisions of substance based on consensus, whereas CEM has a more flexible decision-making structure where initiatives only need agreement between at least three members. This may have consequences for how stakeholders view procedural fairness and distributive fairness.

7.4 Theory-Based Expectations of Legitimacy Assessments

Some of the differences mentioned in the previous section have theoretical value, since they imply expectations about legitimacy assessments. In what follows, we turn to the question of how stakeholders’ assessments of the legitimacy of the five key institutions governing the climate-energy nexus may vary.

The literature has shown that different types of stakeholders hold different legitimacy demands based on their social values, norms, and previous experiences (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2005; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and Vihma Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and Vihma2009; Lenz and Viola Reference Lenz and Viola2017). We argue that legitimacy demands can therefore vary depending on (1) the type of stakeholder (i.e. government, business, or NGO representative); (2) the issues that these stakeholders primarily work with (for example energy, development, or climate change); and (3) where in the world the person comes from, as social values, norms, and experiences can be expected to vary across different legitimacy-granting communities (Symons Reference Symons2011; Nasiritousi et al. Reference Nasiritousi, Hjerpe and Bäckstrand2016). Thus, stakeholder type, focus of work and geographical origin can serve as proxies for differences in norms, values, and experiences that may influence legitimacy assessments.

At the same time, institutional complexity – and the logic of the cognitive model – implies that stakeholders, even if they are experts, may face difficulties in distinguishing their assessments of institutions that are similar in their functions due to bounded rationality (Alter and Meunier Reference Alter and Meunier2009). If it is indeed too hard for stakeholders to disentangle certain properties across institutions with overlapping mandates, e.g. dimensions such as outcome and impact (Bäckstrand et al. Reference Bäckstrand, Söderbaum, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018), the cognitive model of legitimacy would lead us to expect that there will not be great variation in stakeholders’ assessments of the institutions governing the climate-energy nexus. Despite the differences in institutional qualities outlined in the previous section, the five institutions are interrelated and fulfil comparable governance functions within the same subfield, such that stakeholders might draw on similar heuristics to form their legitimacy assessments. In sum, the literature provides reasons to expect both variation and similarity in legitimacy assessments of institutions, across different categories of stakeholders.

Expectations can therefore be drawn up based on the nature of institutions as well as on the background of the stakeholders. The following expectations will guide the exploratory analysis that we present in the remainder of this chapter. First, all five institutions are relatively specialized and rely on expert knowledge as source-based input legitimacy. It is therefore of interest to explore whether stakeholders agree with the institutions’ claims that they are strong on expertise. Given that expertise is an important feature of the institutions studied, we have reasons to believe that the expertise dimension will be positively evaluated by stakeholders. Conversely, because most institutions are more concerned with expertise than the empowerment of marginalized groups, procedural and distributional fairness can be expected to be evaluated more negatively (cf. Nasiritousi et al. Reference Nasiritousi, Hjerpe and Bäckstrand2016).

Second, the selected institutions vary along the nine dimensions of legitimacy. Particularly the UNFCCC fulfils many of the respective normative criteria, with, for example, inclusive membership, relative openness toward nonstate actors, and outputs such as the Paris Agreement and can therefore be expected to rank highly on legitimacy (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee2013). Yet, the cognitive model highlights that legitimacy assessments also depend on the prototype used by actors to form their perceptions (Lenz and Viola Reference Lenz and Viola2017). This implies that, while an institution fulfils many normative criteria of legitimacy, legitimacy assessments may still vary depending on the norms, values and experiences of the community of stakeholders that grant legitimacy.

Third, and linking to the background of stakeholders, we may expect different legitimacy assessments among state actors on the one hand, and nonstate actors on the other. State actors play an important role in intergovernmental organizations, and are likely to take these as a point of reference. For nonstate actors, on the other hand, the prototype used to make an evaluation is likely to be an institution that the nonstate actor is familiar with or wishes for, i.e. a relatively open institution with formal access for nonstate actor participation (Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer and Squatrito2014). Institutions that are relatively closed are therefore more likely to be negatively evaluated by nonstate actors than by government representatives.Footnote 2

Fourth, stakeholders also differ in terms of the issue areas they are predominantly working on. Differences in legitimacy assessments could thus also arise from variations in norms and values that go back to different thematic environments. Stakeholders from a certain community are likely to be more familiar with institutions from their own field than from other issue areas and, subsequently, may well use different heuristics or prototypes. For example, those actors working primarily in the energy sector may be much more familiar with institutions such as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the International Energy Forum than those actors that primarily work in the development sector – who, in turn, may be more familiar with, for example, the Global Environment Facility and the Green Climate Fund. In other words, the frame of reference that actors in global climate and energy governance use for their legitimacy assessments can be assumed to reach far beyond the institutions included in this study.

Finally, we expect to observe differences in legitimacy assessments based on where respondents come from. Both legitimacy norms and heuristics are likely to vary depending on the geographical background of the respondents. For instance, governance norms and expectations, political culture, and level of involvement in international organizations may differ considerably across countries. This said, our sample consists of experts largely active in international circles. This might weaken the differentiating effect of geographical origin as these experts may have experienced a certain socialization into more general and international norms of global governance (Flockhart Reference Flockhart2006; Greenhill Reference Greenhill2010).

In what follows, we use our expectations as an explorative guidance to provide a first empirical mapping of legitimacy assessments for the five selected key institutions governing the climate-energy nexus. This mapping will offer novel insights into how these assessments differ between institutions and stakeholders.

7.5 Data and Methods

This chapter uses unique questionnaire data to capture the assessments of key stakeholders on the different dimensions of input and output legitimacy that we introduced previously (CLIMENGO Expert Survey 2017–2018). Climate and energy experts were surveyed, including representatives from national, regional, and local governments as well as businesses, NGOs, academia, and intergovernmental organizations. The survey was distributed to participants at three venues: the UNFCCC COP23 in Bonn, Germany, November 2017; the UNFCCC intersessional in Bonn, Germany, May 2018; and the Nordic Clean Energy Week that comprised both Mission Innovation and CEM meetings in Malmö, Sweden, and Copenhagen, Denmark, May 2018. At the UNFCCC meetings we handed out questionnaires in side-events with an energy-related focus. We thereby obtained responses from a broad range of public and private stakeholders that work with climate and energy questions.

In addition, we created an online version of the questionnaire to target specific categories of respondents that were not sufficiently covered by the paper version of the survey. As probability sampling was not possible – given that it is not possible to define the population of climate and energy experts in global governance – we aimed at covering a broad variety of stakeholders. This means that, while we can show differences in legitimacy assessments between stakeholder categories, the results cannot be extrapolated to the entire population of climate and energy experts in global governance.

The survey first asked respondents to indicate which type of stakeholder they are, and which issue areas are central to their work. They were also asked to indicate their nationality. Next, respondents were asked how familiar they are with the five institutions of our study. When respondents indicated to be at least somewhat familiar with an institution, they were asked follow-up questions on nine criteria that reflect the different dimensions of legitimacy as identified in the conceptual framework. Respondents were instructed to use a scale that ranges between 1 (very weak) and 5 (very strong) to evaluate each organizations’ expertise, transparency, accountability, inclusion of all appropriate actors, procedural (decision-making) fairness, output (what is produced), outcome (the effect the output has on its members), impact (the effect the outcome has on problem-solving), and distributive fairness (distributing benefits to members fairly).

The survey was completed by 262 respondents in total. Of these, 28 per cent were government representatives, 26 per cent represented an NGO, 23 per cent identified themselves as academics, 17 per cent represented a business organization, and 8 per cent an intergovernmental organization. The largest share of respondents worked with multiple issue areas; most of them with climate mitigation (36 per cent), followed by technology (30 per cent), energy or energy security (30 per cent), development (19 per cent), adaptation (19 per cent), and climate finance and carbon pricing, e.g. carbon markets (17 per cent). Geographically, most respondents hold a European or Western nationalityFootnote 3 (64 per cent); 13 per cent of respondents came from Africa, 15 per cent came from the Asia-Pacific region, and 6 per cent from a Latin American or Caribbean country.

These groupings were used to examine differences in perceptions of stakeholders from different geographical origins. An additional categorization of nationalities was conducted based on the World Bank’s income categories of countries, i.e. low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high. This two-pronged approach allows us to test whether differences in legitimacy assessments stem from differences in norms, values, or experiences held across world regions as determined by geography or by income.

As respondents could indicate multiple actor types and issue areas they were active in, t-tests (rather than analysis of variance, i.e. ANOVA) were performed in order to explore statistical differences in their legitimacy assessments. For each instance, all respondents who indicated to be active within a certain actor type or to be working with a certain issue area were compared to all respondents who were active in a specific other organization, or active in another issue area. Among the surveyed stakeholders, the most well-known organization is the UNFCCC, with 90 per cent of respondents being rather to highly familiar with this organization. Next are the IEA (87 per cent), IRENA (84 per cent), and REN21 (47 per cent), while only 35 per cent of the respondents are at least rather familiar with CEM.Footnote 4

7.6 Results

7.6.1 Exploring Nine Dimensions of Legitimacy

Figure 1 presents assessments by the respondents for each institution and each legitimacy dimension, as well as the average score for all dimensions taken together (‘total average’ in the figure). On the whole, we see that expertise is positively assessed across the institutions. For the IEA, IRENA, REN21, and UNFCCC it ranges between 4 and 4.5 points on the 5-point scale. Specifically, the data show that the level of expertise of the IEA and IRENA is significantly more positively evaluated by the respondents than any other legitimacy dimension of those institutions (confirmed by a t-test). Similarly, for REN21 and the UNFCCC the level of expertise is more positively evaluated than most other dimensions. This is in line with our expectations, as this dimension represents a key feature of the institutions we study and the survey shows that it is recognized accordingly by the respondents.

Figure 7.1 Mean levels of legitimacy assessments per institution.

Additionally, we observe that for the UNFCCC, evaluations of its input legitimacy are on average more positive than those of its output legitimacy. For the other institutions, however, no such division is visible. Furthermore, the evaluation of the input legitimacy of the UNFCCC is higher than that of CEM, IEA, and IRENA, while the perceived output legitimacy of the UNFCCC is similar to that of the IEA, IRENA, and REN21. One possible explanation for the UNFCCC’s strong performance on input dimensions could be that the highly political negotiations have forced the institution to put increased emphasis on strengthening inclusion and transparency to maintain legitimacy, at least in comparison to the other institutions in our study. This has particularly been highlighted in the aftermath of the Copenhagen conference in 2009 (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee2013). Moreover, transparency and inclusion were key to the French Presidency that was successful in concluding the Paris Agreement (Brun Reference Brun2016).

7.6.2 Exploratory Factor Analysis of Legitimacy Dimensions

The next step in the analysis uses exploratory factor analysis in order to examine the underlying structure in the data. Exploratory factor analysis is a statistical method that is used to determine how many distinct constructs are captured by a set of measures, in a case where the researcher does not have definite expectations about the underlying structure of correlations between the observed measures. In other words, it shows whether the measures capture different aspects of one broader construct or whether they capture multiple constructs (Fabrigar and Wegener Reference Fabrigar and Wegener2012).

In this particular study, we test whether the nine dimensions of legitimacy together measure one underlying construct, ‘legitimacy assessments’, or whether they load on two separate factors, as they might as well capture ‘input legitimacy assessments’ on the one hand, and ‘output legitimacy assessments’ on the other. The factor loadings and Eigenvalues of the exploratory factor analyses for each institution indicate that the items indeed load on one underlying factor which we label ‘legitimacy assessments’. Hence, the individual assessments of each legitimacy dimension can be treated as part of a broader measure for legitimacy assessments, in a multi-faceted manner.

For this reason, the composite indicator (a sum-scale ranging from 1 to 5) for perceived legitimacy of each institution was used in the remainder of the study as a measure for respondents’ legitimacy assessments. On average, respondents’ assessment of CEM across the different dimensions of legitimacy (mean=2.845) is less positive than that of any of the other institutions, while the legitimacy assessment of the UNFCCC (mean = 3.707) is the most positive for all institutions in our study (confirmed by t-tests). This suggests that, in comparative terms, the UNFCCC is perceived to meet best the normative expectations of respondents – which corresponds to the institution’s relatively good formal record on some of the criteria. The average overall legitimacy assessments of the IEA, IRENA, and REN21 do not significantly differ from one another. Thus, this first observation indicates that the extent to which institutions formally meet normative legitimacy criteria has an influence on individual legitimacy assessments (cf. Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and McGee2013).

7.6.3 Legitimacy Assessments among Subsets of Stakeholders

We also sought to understand how these legitimacy assessments differ across actors with different backgrounds. As we show in the following, the variation in the data across stakeholder groups qualifies the previous observation: it shows that the formal compliance of an institution with normative legitimacy criteria does not directly translate into stakeholders’ legitimacy assessments. By looking for systematic patterns in the legitimacy assessments of different categories of stakeholders, we seek to better understand what shapes such assessments. Further t-tests were therefore conducted in order to explore how different institutions are perceived by different categories of stakeholders and how the issue areas and geographical backgrounds of respondents might affect their assessments of the different institutions.

Table 7.2 shows how state and nonstate actors ranked the different institutions in terms of legitimacy assessments. The means and reported t-tests in Table 7.2 confirm, for both types of actors, the generally observed pattern of a more negative legitimacy assessment of CEM, and a more positive assessment of the UNFCCC, compared to the other institutions. Yet, in addition to this similarity, we also observe a slightly different rank-order in legitimacy assessments within both categories of respondents. The IEA (mean 3.678) is ranked significantly higher than IRENA (3.479) amongst state actors, while not being ranked significantly lower than the UNFCCC. Among nonstate actors, REN21 is not assessed as significantly less legitimate than the UNFCCC.

Table 7.2 Legitimacy Assessments of Institutions, structured by actor type.

| Mean | SE | 95% CI | N | Results t-tests | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State actors | ||||||

| CEM | 3.026 | 0.206 | [2.590–3.462] | 17* | Significantly lower than all other | |

| REN21 | 3.411 | 0.259 | [2.825–3.998] | 10* | ||

| IRENA | 3.479 | 0.149 | [3.175–3.783] | 29 | ||

| IEA | 3.678 | 0.116 | [3.440–3.916] | 29 | Significantly higher than IRENA and CEM | |

| UNFCCC | 3.714 | 0.130 | [3.448–3.979] | 31 | Significantly higher than all but IEA | |

| Nonstate actors | ||||||

| CEM | 2.739 | 0.149 | [2.434–3.045] | 29 | Significantly lower than all other | |

| IRENA | 3.540 | 0.084 | [3.372–3.708] | 63 | ||

| IEA | 3.577 | 0.083 | [3.411–3.743] | 72 | ||

| REN21 | 3.655 | 0.122 | [3.407–3.903] | 37 | ||

| UNFCCC | 3.705 | 0.071 | [3.564–3.845] | 87 | Significantly higher than all but REN21 |

Notes: * Few respondents within this category were sufficiently familiar with the institution in order to evaluate it on all legitimacy dimensions. Results should be interpreted with this caution in mind. Given the modest sample size, a 90 per cent confidence level is used as the cut-off point for significance testing.

Table 7.3 pairs these figures according to state and nonstate actors’ legitimacy assessments for each institution. The means and t-tests further indicate significant differences in the legitimacy assessments among these two actor groups. Assessments of CEM are significantly lower among the surveyed nonstate actors than among the state actors. By contrast, legitimacy assessments of REN21 are significantly more positive among nonstate actors than among state actors. This observation suggests that the inclusion of nonstate actors in an institution plays a role in shaping legitimacy assessments: CEM is the organization with the least access to nonstate actors in our study, while REN21 is the most open one, being a multi-stakeholder network that reaches out to a broad range of nonstate actors in the public and private sectors. Hence, nonstate actors may be more familiar with REN21 so that this institution might be incorporated in their heuristics of what a legitimate climate and energy governance institution could look like. (Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer and Squatrito2014; Lenz and Viola Reference Lenz and Viola2017).

Table 7.3 Legitimacy Assessments of Institutions, structured by institution and actor type.

| Mean | SE | 95% CI | N | T-test (t) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM | |||||

| State actors | 3.026 | 0.206 | [2.590–3.462] | 17* | |

| Nonstate actors | 2.739 | 0.149 | [2.434–3.045] | 29 | |

| −1.925 (p<0.05) | |||||

| IEA | |||||

| State actors | 3.678 | 0.116 | [3.440–3.916] | 29 | |

| Nonstate actors | 3.577 | 0.083 | [3.411–3.743] | 72 | |

| −1.215 (ns) | |||||

| IRENA | |||||

| State actors | 3.479 | 0.149 | [3.175–3.783] | 29 | |

| Nonstate actors | 3.540 | 0.084 | [3.372–3.708] | 63 | |

| 0.727 (ns) | |||||

| REN21 | |||||

| State actors | 3.411 | 0.259 | [2.825–3.998] | 10* | |

| Nonstate actors | 3.655 | 0.122 | [3.407–3.903] | 37 | |

| 1.992 (p<0.05) | |||||

| UNFCCC | |||||

| State actors | 3.714 | 0.130 | [3.448–3.979] | 31 | |

| Nonstate actors | 3.705 | 0.071 | [3.564–3.845] | 87 | |

| –0.131 (ns) |

Notes: * Few respondents within this category were sufficiently familiar with the institution in order to evaluate it on all legitimacy dimensions. As for CEM and REN21, few state actors are included, and the variances in legitimacy assessments were compared between the largest and smallest group following de Winter (2013). As the variances are relatively equal, the likelihood of Type I error (i.e. observing a false positive result) is low.

Table 7.4 shows how respondents rank institutions differently depending on whether they work in: energy security and technology; climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation; or adaptation and development. While these categories are partially overlapping, they help distinguish actors according to their main domain (energy, climate, or development).Footnote 5 A simple ranking of the mean legitimacy assessment of the five institutions for each category of respondents again shows that CEM is ranked the lowest and the UNFCCC the highest. Yet, no statistically significant differences are detected between the institutions among the adaptation and development respondents. At least for CEM and REN21, this is most likely due to the limited number of respondents. For the climate finance, carbon pricing, and mitigation group, we do observe that the UNFCCC is ranked significantly higher than all other institutions, the IEA significantly higher than IRENA and CEM, and CEM significantly lower than all other institutions. Furthermore, CEM is ranked significantly lower than all other institutions for the energy security and technology respondents. This last finding is counterintuitive, given that CEM has a clear focus on energy and technology questions.

Table 7.4 Legitimacy Assessments of Institutions, structured by stakeholders’ work focus.

| Mean | SE | 95% CI | N | Results t-tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy security and technology | |||||

| CEM | 3.044 | 0.147 | [2.743–3.345] | 28 | Significantly lower than all other institutions |

| REN21 | 3.545 | 0.183 | [3.165–3.926] | 22* | ‡ |

| IRENA | 3.632 | 0.101 | [3.428–3.835] | 48 | |

| IEA | 3.667 | 0.088 | [3.489–3.844] | 54 | |

| UNFCCC | 3.795 | 0.085 | [3.625–3.964] | 56 | Significantly higher than all but REN21 (given ‡) |

| Climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation | |||||

| CEM | 2.667 | 0.171 | [2.306–3.027] | 18* | Significantly lower than all other institutions |

| IRENA | 3.452 | 0.093 | [3.264–3.640] | 43 | |

| REN21 | 3.545 | 0.164 | [3.202–3.889] | 21* | |

| IEA | 3.618 | 0.102 | [3.413–3.824] | 46 | Significantly higher than IRENA and CEM |

| UNFCCC | 3.761 | 0.088 | [3.585–3.937] | 57 | Significantly higher than all other institutions |

| Adaptation and development | (no significant differences between the evaluations of the institutions) | ||||

| CEM | 2.570 | 0.281 | [1.967–3.174] | 15* | ‡ |

| REN21 | 3.299 | 0.200 | [2.864–3.735] | 13* | No significant differences |

| IRENA | 3.379 | 0.160 | [3.050–3.707] | 27 | |

| IEA | 3.449 | 0.149 | [3.143–3.755] | 26 | |

| UNFCCC | 3.511 | 0.141 | [3.227–3.796] | 39 |

Notes: * Few respondents within this category were sufficiently familiar with the institution in order to evaluate it on all legitimacy dimensions. ‡Following the method of de Winter (2013), no comparison could be made between the mean perceived legitimacy among these respondents. The variance is too high for this small group of observations, compared to variances of the other means in the analysis. Given the modest sample size, a 90 per cent confidence level is used as the cut-off point for significance testing.

Table 7.5, which rearranges these issue-area-based figures along the five institutions, sheds more light on this observation about CEM. Overall, respondents working with energy security and technology tend to have the most positive legitimacy assessments; those working with adaptation and development have the least positive ones. Moreover, for both CEM and IRENA, the difference between respondents working with energy security and technology and respondents mainly working with other issues is most pronounced. In other words, respondents for whom energy security and technology is most central to their work tend to assess the legitimacy of those institutions that focus most strongly on these issues as particularly more positive than other respondents. For institutions that, next to energy security and technology, also focus on mitigation, climate finance and carbon pricing, development, and adaptation (IEA and UNFCCC), we observe that the legitimacy assessments are not significantly different among respondents working with energy security and technology and those working with climate finance, carbon markets and pricing, and mitigation. This again suggests the importance of the thematic foci of the institutions for the legitimacy assessments of stakeholders. Respondents who work with adaptation and development make the most negative legitimacy assessments for all institutions, even for the UNFCCC, although adaptation and low-carbon development feature prominently on that institution’s agenda.

Table 7.5 Legitimacy Assessments of Institutions, structured by institution and stakeholders’ work focus.

| Mean | SE | 95% CI | N | T-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM | |||||

| 1. Energy security and technology | 3.044 | 0.147 | [2.743–3.345] | 28 | 1 vs. 2: t=2.569, p<0.01 1 vs. 3: ‡ |

| 2. Climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation | 2.667 | 0.171 | [2.306–3.027] | 18* | 2 vs. 1: t=-2.208, p<0.05 2 vs. 3: ‡ |

| 3. Adaptation and development | 2.570 | 0.281 | [1.967–3.174] | 15* | 3 vs. 1: ‡ 3 vs. 2: ‡ |

| IEA | |||||

| 1. Energy security and technology | 3.667 | 0.088 | [3.489–3.844] | 54 | 1 vs. 2: t=0.551, ns 1 vs. 3: t=2.462, p<0.01 |

| 2. Climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation | 3.618 | 0.102 | [3.413–3.824] | 46 | 2 vs. 1: t=-0.477, ns 2 vs. 3: t=1.661, p<0.1 |

| 3. Adaptation and development | 3.449 | 0.149 | [3.143–3.755] | 26 | 3 vs. 1: t=-1.469, p<0.1 3 vs. 2: t=-1.140, ns |

| IRENA | |||||

| 1. Energy security and technology | 3.632 | 0.101 | [3.428–3.835] | 48 | 1 vs. 2: t=1.779, p<0.05 1 vs. 3: t=2.500, p<0.001 |

| 2. Climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation | 3.452 | 0.093 | [3.264–3.640] | 43 | 2 vs. 1: t=-1.932, p<0.05 2 vs. 3: t=0.787, ns |

| 3. Adaptation and development | 3.379 | 0.160 | [3.050–3.707] | 27 | 3 vs. 1: t=-1.586, p<0.1 3 vs. 2: t=-0.459, ns |

| REN21 | |||||

| 1. Energy security and technology | 3.545 | 0.183 | [3.165–3.926] | 22* | 1 vs. 2: t=0.003, ns 1 vs. 3: t=2.569, p<0.01 |

| 2. Climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation | 3.545 | 0.164 | [3.202–3.889] | 21* | 2 vs. 1: t=-0.002, ns 2 vs. 3: t=1.496, p<0.1 |

| 3. Adaptation and development | 3.299 | 0.200 | [2.864–3.735] | 13* | 3 vs. 1: t=-1.230, ns 3 vs. 2: t=-1.230, ns |

| UNFCCC | |||||

| 1. Energy security and technology | 3.795 | 0.085 | [3.625–3.964] | 56 | 1 vs. 2: t=0.398, ns 1 vs. 3: t=3.355, p<0.001 |

| 2. Climate finance, carbon pricing and mitigation | 3.761 | 0.088 | [3.585–3.937] | 57 | 2 vs. 1: t=-0.388, ns 2 vs. 3: t=2.849, p<0.01 |

| 3. Adaptation and development | 3.511 | 0.141 | [3.227–3.796] | 39 | 3 vs. 1: t=-2.018, p<0.05 3 vs. 2: t=-1.777, p<0.05 |

Notes: * Few respondents within this category were sufficiently familiar with the institution in order to evaluate it on all legitimacy dimensions. ‡ Given the low N of one of the categories in the comparison, the variances in legitimacy assessments were compared between the largest and smallest group following de Winter (2013). When the variances are relatively equal or when the variance is smaller in the category with the lowest N, the likelihood of Type I error (i.e. observing a false positive result) is low. In these cases, the result of the t-test is presented. Where this criterion is not met, the result of the t-test is omitted.

These observations are in line with one of our aforementioned expectations, namely that differences in legitimacy assessments could stem from differences in norms and values amongst communities of stakeholders working on similar issues, or from differences in the institutions that they are familiar with and use as heuristics or prototypes. According to the cognitive model, the observed positive assessments of respondents working on issues of energy security and technology would be explained by their higher level of familiarity with institutions that fulfil fewer criteria for normative legitimacy, which in turn would reflect in the heuristics they use to compare the five institutions in our study against. In comparison to those, they assess the five climate-energy institutions in our study more favourably. For example, if respondents working mainly with energy issues take institutions such as OPEC and the International Energy Forum as reference points, the five institutions in this study could be considered more legitimate as they fulfil more normative criteria, particularly in terms of openness and transparency.

By contrast, those respondents working on issues of adaptation and development tend to be familiar with institutions that fulfil rather more criteria for normative legitimacy. Compared to such prototypes, they would assess the five climate-energy institutions less favourably. For example, the Global Environment Facility and the Green Climate Fund that focus more on development issues may constitute such reference institutions (in terms of heuristics) for the respondents who work mainly on adaptation and development. Particularly the Global Environment Facility has been discussed as a potential role model for other international institutions due to its inclusiveness and openness toward a diversity of actors (Streck Reference Streck2001).

In summary, we can expect the prototype institutions to differ considerably across groups of respondents, which could explain a large part of the difference in legitimacy assessments that we found for our sample. This said, this connection needs to be further corroborated, since our survey data does not include information on the heuristic that respondents had in mind when assessing the five institutions. The focus of our study, thus, remains exploratory and descriptive, yet it suggests avenues for further explanatory research.

Finally, we explored whether significant variations can be observed in the legitimacy assessments by respondents from countries with different economic backgrounds, or from different geographical regions (Africa, Asia and Pacific, Latin America and Caribbean, and European and other Western countries). For the UNFCCC, we indeed observe such a significant difference. Respondents from high-income countries (as categorized by the World Bank) perceive the UNFCCC as significantly more legitimate (mean= 3.773) than respondents from other countries (mean= 3.563; t= 2.912; p=0.002). Moreover, no significantly different views about the legitimacy of the UNFCCC are observed for respondents from middle- and low-income countries. Neither did we observe a significant difference in evaluations of the other institutions when we grouped respondents by national-income category.Footnote 6

This is rather surprising, given that both norms and values and what institutions respondents are familiar with would be expected to vary with the geographic origin of the respondent. It may be that many of the respondents are international elites and have therefore been socialized or self-selected into similar norms, and are hence used to similar international institutions. Thus, we might indeed be looking at dynamics of a transnational elite that is divided by professional focus, rather than by nationality – since we did observe distinctions in legitimacy assessments across respondents from different sectors and types of organizations. In fact, previous research supports this assumption: Verhaegen et al. Reference Verhaegen, Scholte and Tallberg2018, for instance, showed that there is more variation in legitimacy perceptions of global governance institutions between elites of different societal sectors than between elites from different countries.

7.7 Conclusions

The aim of this chapter was to provide a first mapping of stakeholders’ assessments of the legitimacy of five key institutions governing the climate-energy nexus. Against the backdrop of considerable institutional complexity, and scarce resources amongst public and private actors to enhance participation in global governance, we wanted to better understand to what extent key institutions in global climate and energy governance are seen as legitimate by key stakeholders.

The analyses showed that, on the one hand, there are many similarities in the legitimacy assessments of the five institutions we put under scrutiny – with the mean legitimacy assessments ranging between 2.845 (CEM) and 3.707 (UNFCCC) on a scale from 1 to 5. On the other hand, we also found systematic differences across stakeholders of different types, working with different issues and – to a limited extent – coming from different countries.

Specifically, we observed that CEM is systematically assessed as the least legitimate, and the UNFCCC as the most legitimate, of the five institutions. Second, our analyses showed that the legitimacy assessments of nonstate actors are more positive toward institutions that are more inclusive toward this type of stakeholders. Third, we observed that stakeholders working with energy security and technology, and those working with climate finance, carbon pricing, and mitigation have more positive legitimacy assessments of institutions that more strongly focus on their issues. By contrast, respondents working with adaptation and development issues assessed the legitimacy of the selected institutions more negatively than the other respondents, even for the UNFCCC, which is the global institution in our sample that most strongly engages with these issues. We can only speculate about the reasons for this. Our study has highlighted the possibility that differences in these communities’ norms, values, and experiences contribute to different heuristics being used to make assessments. Yet, whether such differences ultimately stem from processes of socialization or whether they are rather due to functionalist or rationalistic reasons is a pertinent question for future research.

These limitations notwithstanding, the results of our unique survey allow us to draw a set of novel conclusions. First, the results appear to support the view that stakeholders do not adequately disentangle their legitimacy assessments of individual institutions that have similar functions and overlapping mandates. Perhaps this is a reflection of the relatively high level of coordination in the renewable energy subfield (Sanderink, Chapter 4), which means that institutions in this subfield interact extensively with one another and thereby make it difficult for stakeholders to distinguish their respective performance. Within each category of stakeholders, we found comparable assessments and similar legitimacy rankings for these institutions, albeit with some small significant differences. We have reasons to believe that, in order to navigate in a very complex governance field, the surveyed stakeholders form their assessments based on a comparison with institutions that are familiar to, or valued by them. Faced with incomplete information and due to bounded rationality, stakeholders use mental shortcuts to make such comparisons and base their legitimacy assessments thereupon.

Second, the differences in legitimacy assessments found between governmental versus nonstate actors, and across stakeholders working on different issue areas, suggest that international institutions have to pursue different legitimation strategies for different audiences (Gronau and Schmidtke Reference Gronau and Schmidtke2016; Bäckstrand and Söderbaum Reference Bäckstrand, Söderbaum, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Verhaegen et al. Reference Verhaegen, Scholte and Tallberg2018). Knowing one’s audiences is particularly important for institutions that seek to establish and maintain legitimacy in an increasingly crowded field.

Third, and more generally, a stakeholder’s level of familiarity with an institution appears to be linked to a more positive assessment of legitimacy. It therefore does not come as a surprise that international institutions increasingly engage in outreach activities, especially on social media – in order to promote their work to a diversity of actors and seek input from them.

While these findings advance the research frontier on legitimacy, the reliance on survey data comes with the usual set of shortcomings, which means that the findings need to be confirmed in future studies. First, there is always the possibility that respondents either think of the institution as a whole or just the secretariat or another institutional body, which makes a straight-off comparison difficult (Zaum Reference Zaum and Zaum2013). Second, we followed a notion of cognitive legitimacy whereby respondents’ assessments are based on comparisons with heuristic or prototype institutions. Which particular heuristic institutions that are used by respondents lies beyond the scope of this study. The first explorative results offered in this chapter should therefore be examined in further, especially interview-based, studies. These could also delve deeper into questions such as how expertise, which is considered key for international institutions in the climate-energy nexus, is conceptualized by stakeholders. Finally, the links to other explanatory variables, such as resources, staffing, or relations to other institutions, should be pursued to further understand assessments of legitimacy.

This study also opens up empirical avenues for further research. It provided a first mapping of stakeholders’ perceptions of nine legitimacy dimensions across five institutions for one particular subfield. An examination of institutions from other subfields could provide insights into how the level of coherence within institutional complexes affects issues of legitimacy. Next steps could also measure differences in how stakeholders view the relative importance of the nine dimensions, or other dimensions of legitimacy not included in this study, to also learn about the sociological legitimacy of the institutions. An interesting and policy-relevant line of inquiry is how low assessments of certain dimensions of legitimacy can be, and amongst which groups of stakeholders, before the institution faces a legitimacy crisis. An answer to that question would, however, require a much larger survey of stakeholders. One limitation of this study has been that the survey includes too few cases (N) in order to do a multivariate analysis that allows comparing the relationship between actor type, issue area, and geographical origin on the one hand, and assessments of legitimacy of the five global climate and energy institutions on the other. A larger research effort would be needed to address this limitation. Such a research effort would also be useful to provide a more fine-grained analysis of differences in legitimacy assessments between different categories of nonstate actors, such as businesses and civil society organizations.

Finally, considerations of legitimacy will always be of major importance for policy makers when deciding on which institution to work with and invest in. Institutional complexity affects these conditions, as institutions and their legitimacy have become highly entangled. Therefore, further research questions, such as about the role of legitimation and delegitimation strategies under institutional complexity, merit further enquiry, as such strategies are likely to affect institutions differently, depending on the norms, values, and experiences of the legitimacy-granting communities.

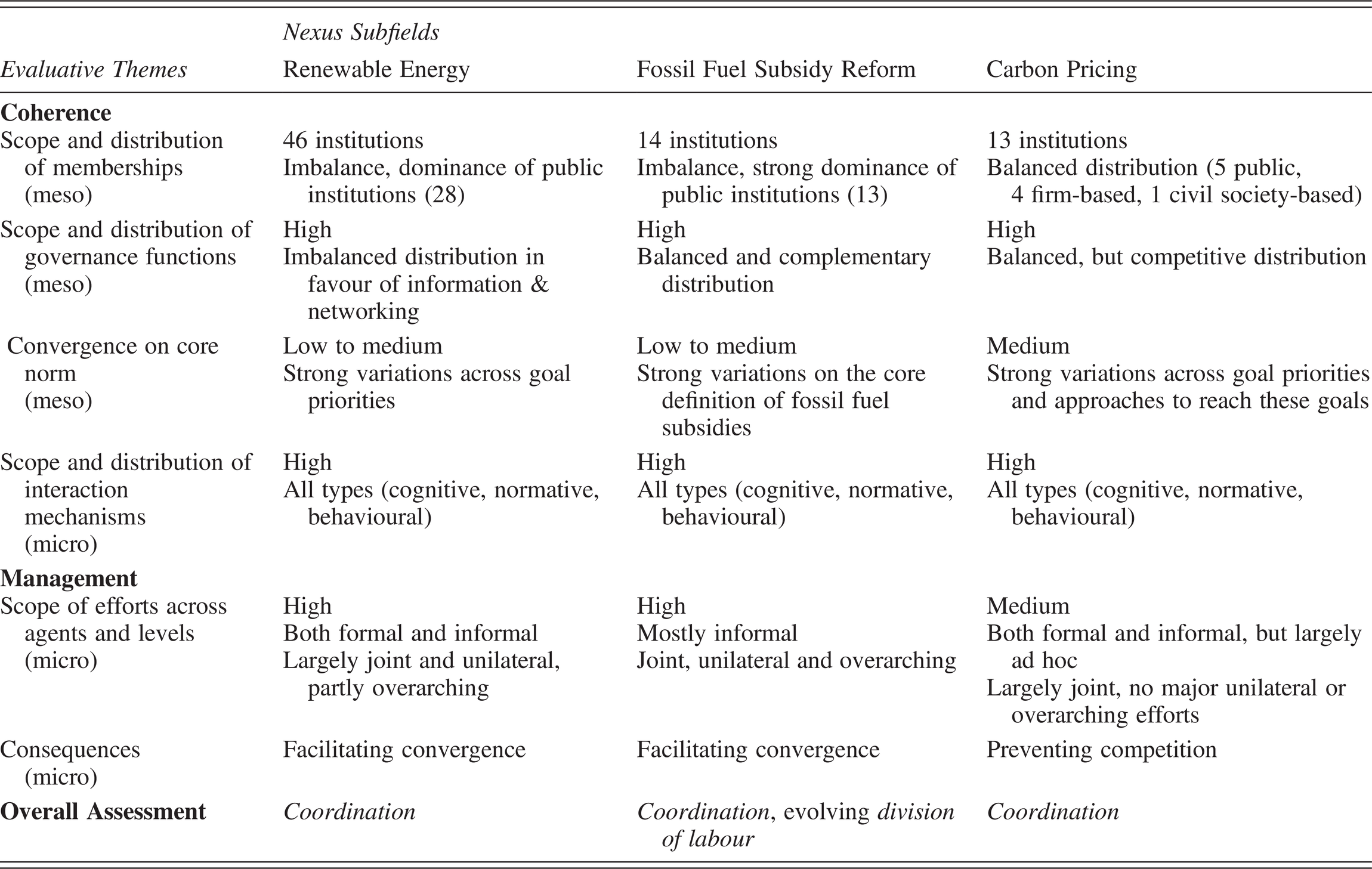

8.1 Introduction

What does institutional complexity mean for performance in the climate-energy nexus? As previous chapters have shown, the nexus is made up of a diverse set of institutions that have overlapping mandates and functions. Chapter 3 showed how the institutional complex varies at the meso level, and Chapters 4–6 explored the interactions between different institutions in three selected subfields: renewable energy, fossil fuel subsidy reform, and carbon pricing. Given the large number of institutions that operate and interact in these fields, several questions arise about their performance and environmental effectiveness: what are the consequences of this intricate web of institutions for the performance of the institutional complex of the climate-energy nexus? Is institutional complexity a requirement for effective problem-solving, or does it hamper effectiveness? What management options exist for making the institutional complex at the climate-energy nexus more effective? Considering the magnitude of the climate- and energy-related challenges, the answers to these questions are of great importance to both scholars and practitioners.

Based on these questions, and building on the previous chapters, the aim of this chapter is to assess the effectiveness of each of the three subfields as well as to discuss the overall performance of the institutional complex of the climate-energy nexus. As outlined in Chapter 2 and elaborated on in the next section, effectiveness here refers to how well institutions perform in terms of achieving goals that they have been tasked to fulfil. By examining the outputs, outcomes, and impacts of the three subfields, the chapter shows both the advantages and the disadvantages of institutional complexity of the climate-energy nexus for achieving effectiveness. It further shows that, despite the difficulties with evaluating effectiveness under institutional complexity, such an assessment is a worthwhile exercise in order to identify management options – i.e. options for formally regulating the linkage between institutions – for the climate-energy nexus.

The chapter proceeds as follows. The next section discusses the concept of effectiveness and the challenges to analyzing the effectiveness of institutions, especially when they have overlapping mandates and are interlinked. Thereafter, our methodology section outlines how, in order to respond to these challenges, our research relies on a two-track approach, integrating assessments by researchers and interviews with key stakeholders. Based on this information, we evaluate the outputs, outcomes, and impacts of institutions within each subfield. Thereafter, we examine what the consequences of institutional complexity are for the subfield in question. The insights gained from this analysis are then used to outline management options for the institutions of the climate-energy nexus. The final section concludes with discussing implications of our findings for the governance of the nexus at large.

8.2 Conceptualizing Effectiveness

As discussed in Chapter 2, effectiveness can be evaluated in different ways. Easton (Reference Easton1965) suggested measuring effectiveness across three dimensions: output, outcome, and impact. Output concerns performance in terms of what the institution produces, for example issuing regulations (binding or non-binding), producing reports, conducting research, organizing meetings, providing funding, offering training, etc. (Szulecki et al. Reference Szulecki, Pattberg and Biermann2011). Outcome relates to whether the institution produces behavioural changes, for example in terms of whether it increases the level of cooperation and compliance amongst members, for instance by improving learning and modifying incentives (Underdal Reference Underdal, Miles, Underdal, Andresen, Wettestad, Skjærseth and Carlin2002; Gutner and Thompson Reference Gutner and Thompson2010). To determine an institution’s impact implies assessing the extent to which the institution contributes to alleviating the problem it was tasked to resolve (Underdal Reference Underdal, Miles, Underdal, Andresen, Wettestad, Skjærseth and Carlin2002). Impacts may include effects that are positive or negative, direct or indirect, intentional or unintentional, and these can be short-, medium-, or long-term (Alcamo Reference Alcamo2017). This threefold understanding implies that effectiveness is a stronger term than performance, since institutions can perform well in terms of output but nevertheless not achieve the intended impacts necessary for goal attainment.

Measuring effectiveness becomes increasingly difficult as the number of institutions rises. Even just for one institution, assessing effectiveness is challenging because of the need to establish causality between the output of the institution, the behavioural change among the target actors, and the impact on the problem that the institution was tasked to solve. This challenge is multiplied under institutional complexity because of the question of attribution, namely which institutions are responsible for observed impacts in a web of institutions with overlapping mandates? In short, under institutional complexity, the difficulties involved in assessing effectiveness are compounded by challenges in identifying the division of labour between institutions (Alter and Meunier Reference Alter and Meunier2009).

Moreover, when evaluating impact for a field with multiple institutions, the analysis shifts from assessing goal attainment for individual institutions to assessing how the work of multiple institutions affects an overall goal, such as the fulfilment of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 on sustainable energy in the case of the renewable energy subfield. This approach is different from what can be found in much of the previous literature on effectiveness, where the focus is either on assessing institutional or environmental effectiveness (Underdal Reference Underdal, Miles, Underdal, Andresen, Wettestad, Skjærseth and Carlin2002; Gutner and Thompson Reference Gutner and Thompson2010; Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito and Lundgren2016). Analyses of institutional effectiveness look at institutional performance, also including assessments of output legitimacy, such as the one presented in Chapter 7. Studies on environmental effectiveness, on the other hand, look at the extent to which specific institutions have an impact on environmental indicators. In contrast, the analysis in this chapter looks at the extent to which the collective contributions of individual institutions within a subfield are successful in fulfilling common goals in the subfield.