8 Measuring results

Accurate measurement has become something of a holy grail in development finance, viewed as a mythical key to figuring out what works and what does not – and why. The pursuit of better ways of measuring and assessing development successes and failures is not new. Yet the forms measurement takes and the roles it plays have evolved. As the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and key donors have adopted the new strategies that I have discussed in previous chapters – new standards of governance and transparency, policies aimed at fostering local ownership and reducing vulnerability and risk – they have also developed ever more complex models, indicators and matrixes to try to measure these policies and their effects. In the process, there has emerged a veritable industry surrounding policy measurement and evaluation. These new practices of measurement represent an important new governance strategy – one that not only follows from the other three discussed so far in this book, but which also plays a crucial role in making them possible.

Such efforts to redesign measurement techniques can be seen in a wide range of different international financial institution (IFI) and donor policies – including efforts to define and operationalize ownership, develop new governance indicators, measure compliance with new standards and codes, and assess risk and vulnerability. Different institutions have tackled these challenges in diverse ways. Yet one theme that has been consistent in virtually all of the organizations that I have looked at has been the attempt to reorient measurement around results.1 This new results-oriented approach to measurement and evaluation has played an important role in the shift towards the more provisional form of governance that I have been discussing in this book.

This chapter will move beyond the IMF and World Bank and consider various donors, international agreements and organizations in order to trace the spread of the ideas and practices underpinning the current focus on results. Even more than those of standardization, ownership and risk management, the emergence of the results strategy can only be fully appreciated by moving beyond individual IFIs, tracing the evolution of new practices within a wider community of organizations, and focusing on the meso-level of analysis – the specific techniques, ideas, actors and forms of power and authority through which these institutions have sought to measure results.

Why does measurement matter? I began this book by suggesting that a decade and a half ago, key players in finance and development faced a serious erosion of their expert authority in the context of several contested failures. These failures precipitated significant debates about what constituted success and failure in development finance – debates that were, at their heart, about questions of measurement: if so many past policies that were once deemed successes had in fact resulted in failure, then clearly something needed to be done not only about how development finance was performed, but also about how its successes and failures were measured. One of the key means of re-founding expert authority has therefore been through the development of new ways of measuring and evaluating policies – not just their inputs and outputs, but also their outcomes, or results, providing a new metric for defining success and failure. The hope of the various organizations adopting these measurement strategies is that by demonstrating successful results they will be able to justify their policies, thus re-legitimizing development efforts by re-establishing them on sound methodological grounds.

As I suggested in Chapter 2, the politics of failure is closely linked to the process of problematization. Debates about failure often lead to the identification of new problems and the development of new ways of governing them. In fact, in the case of the practice of results measurement, its history is long enough that we can actually identify two key moments of problematization, the first and more significant of which was triggered by a belief in the failure of government in the 1980s, leading to the introduction of the practice of results management into Western bureaucracies, and the second of which was triggered by the perceived failure of aid, making results a central element of the aid effectiveness agenda in the 1990s and 2000s.

While demonstrating the results of development policy initiatives may sound relatively straightforward, it is in fact a very ambitious undertaking. This effort to develop new kinds of measurement is both a methodological and an epistemological exercise. As different development practitioners, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and state leaders have debated whether and how to focus on results, they have also been contesting the basis of development expertise. Drawing on the insights of Michel Callon and Bruno Latour in this chapter, I will examine how these new measurement techniques work to create a new kind of fact. While talking about “evidence-based” policies, they have also sought to reconstitute what counts as evidence.2 Results-based measurement involves a promise of a new way of knowing not just how to count economic activities, but also what can be counted, and therefore what counts.

Those involved in developing and implementing the strategy of results-based measurement thus not only draw on particular, small “i” ideas – new public management, public choice theory and participatory development – but also seek to transform the epistemological underpinnings of expertise. They do so using two principle techniques: performative inscriptions such as the “results chain,” and various technologies of community that reach out to civil society and other affected groups. Advocates of the results agenda seek to enrol a range of new actors in the practices of measurement and evaluation, particularly bureaucrats in both lending agencies and recipient countries. Although by engaging new actors the strategy does redistribute a measure of expert authority to a wider group, it also seeks to reconstitute them into more results-oriented kinds of actors, through the development of a “results culture.” Power dynamics thus remain a key dimension of this governance strategy, although they often take less direct forms than in the past.

As measurement techniques have become integrated into the day-to-day work of development policy, international organizations (IOs) and donors are seeking to govern through measurement. They are engaging in a highly provisional form of governance practice: one that seeks proactively to transform the culture of evaluation so profoundly that bureaucratic actors change the way that they develop programs by anticipating their ultimate results. This is an indirect form of governance, operating through the most peripheral and technical of arenas – measurement and evaluation – in an effort to transform the assumptions underpinning the management of development finance. And while results may appear like the most concrete of policy objectives, they in fact depend on a highly constructed and symbolic set of techniques – the results chain – in order to be made visible. The symbolic character of the assumptions underpinning the results agenda does occasionally threaten its credibility. Yet, paradoxically, its proponents are able to exploit these leaps of logic in order to deliver good results in often-questionable circumstances, thus hedging against the risk of failure.

Where it came from

Although results-based measurement has only dominated development lending over the past five years, it has a much longer history. This recent reorientation around results can be linked back to two small “i” ideas and an influential technique – new public management thinking, participatory development and evaluation, and the logical framework or “LOGFRAME” approach to development projects. Current results-based thinking and practice is increasingly driven by top-down new public management and LOGFRAME-style analysis; however, it has integrated a measure of the more bottom-up participatory approach and language. The potency and appeal of the idea of results owes a great deal to the fact that it can be understood from these rather different starting places, even though in recent years the strategy has moved away from its participatory roots.

The “failure” of government and new public management

New public management and results-based measurement emerged in response to a widespread – if contested – problematization of the role of the public sector in the 1980s and 1990s in the wake of the purported failure of “big government.” The public sector had expanded massively after the Great Depression and the Second World War, in order to provide social and political stability to support the economy. Keynesian economic theory, emphasizing the central role for government in smoothing out the wider swings of the business cycle, played a crucial role in both legitimizing and operationalizing the public sector’s role. The oil crises and stagflation of the 1970s seriously undermined elite support for this economic model, and Keynesian economic ideas – and the governments that had sought to implement them – came under increasing attack. Leading the charge were public choice theorists and their supporters in the newly elected conservative governments in the UK and the US, where Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were now in power.3

The theoretical underpinnings of the new public management ideas that began to transform government practice are relatively straightforward: public management gurus such as David Osborne and Ted Gaebler sought to adapt the insights of public choice theory to the practices of government agencies – and in doing so to transform them from bureaucracies into something that resembled the rapidly changing face of private sector organizations.4,5 As I have discussed in earlier chapters, public choice theory seeks to apply economic conceptions of humans as essentially rational self-interested maximizers to a wide array of different non-economic contexts.6 Doing so leads public choice scholars to the premise that markets are the most effective means for achieving an optimal distribution of goods and economic growth.

While public choice advocates therefore tend to support the transfer of all possible activities to the private sector, they nonetheless recognize the need for some governmental role – particularly for the provision of public goods that would otherwise be underprovided. Yet they remain deeply suspicious of traditional public bureaucracies, seeing them as a source of inefficient rent-seeking and thus a major drag on growth. In the 1980s and 1990s, new public management scholars sought to solve this dilemma by proposing wide-ranging changes to the public sector (symbolized by the shift from “public administration” to “public management” as the preferred term).7 The goal was quite simply to make the public sector operate more like the private sector – by introducing competition, individual responsibility and performance evaluations based on results.

This problematization of results thus emerged out of claims about the failure of government. Amidst the widespread debate about the causes of the economic set-backs of the 1970s and early 1980s, new public management proponents argued that there had been a fundamental failure in how government worked: they saw the traditional public service’s emphasis on collective responsibility and accountability as misguided and sought to develop a way of doing government’s work that would mimic firms by individualizing responsibility. The key to doing so was to link individuals’ or units’ actions to results, making them responsible for their own successes and failures – and thus hopefully reducing the prevalence of policy failure.

This new way of managing the public sector soon took off in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and Australia.8 New Zealand became the poster child for public choice advocates, showcased by the World Bank among others as a model of public sector reform.9 Beginning in 1988, the government introduced massive institutional reforms, transforming relationships between government and public service into a series of contractual arrangements in which managers were responsible for the delivery of specific results but had significant discretion over how to meet them. As Alan Schick, a consultant with the World Bank’s Public Sector Group, noted in a 1998 paper, “New Zealand has brought its public management much more closely into line with institutionalist economics and with contemporary business practices.”10

The first wave of interest in results-based management was as much neoliberal as it was neoconservative in flavour, driven by a belief in reducing the size of government. Results-based measurement thus survived the end of the Thatcher–Reagan era and, in the mid-1990s, began to take a more widespread hold among Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, becoming, for example, the centrepiece of Vice President Al Gore’s National Performance Review in the United States and of Paul Martin’s Program Review in Canada.11 The OECD championed the spread of such policies to all industrialized nations, arguing for “a radical change in the ‘culture’ of public administration” in order to improve public sector “efficiency and effectiveness.”12

Results in development agencies

The growing popularity of new public management soon took hold in development organizations, particularly among bilateral donors. Performance management became the watchword, and results the key determinant of success. This new enthusiasm for measuring results combined with two other already-present trends within the aid community – LOGFRAME analysis and participatory development.

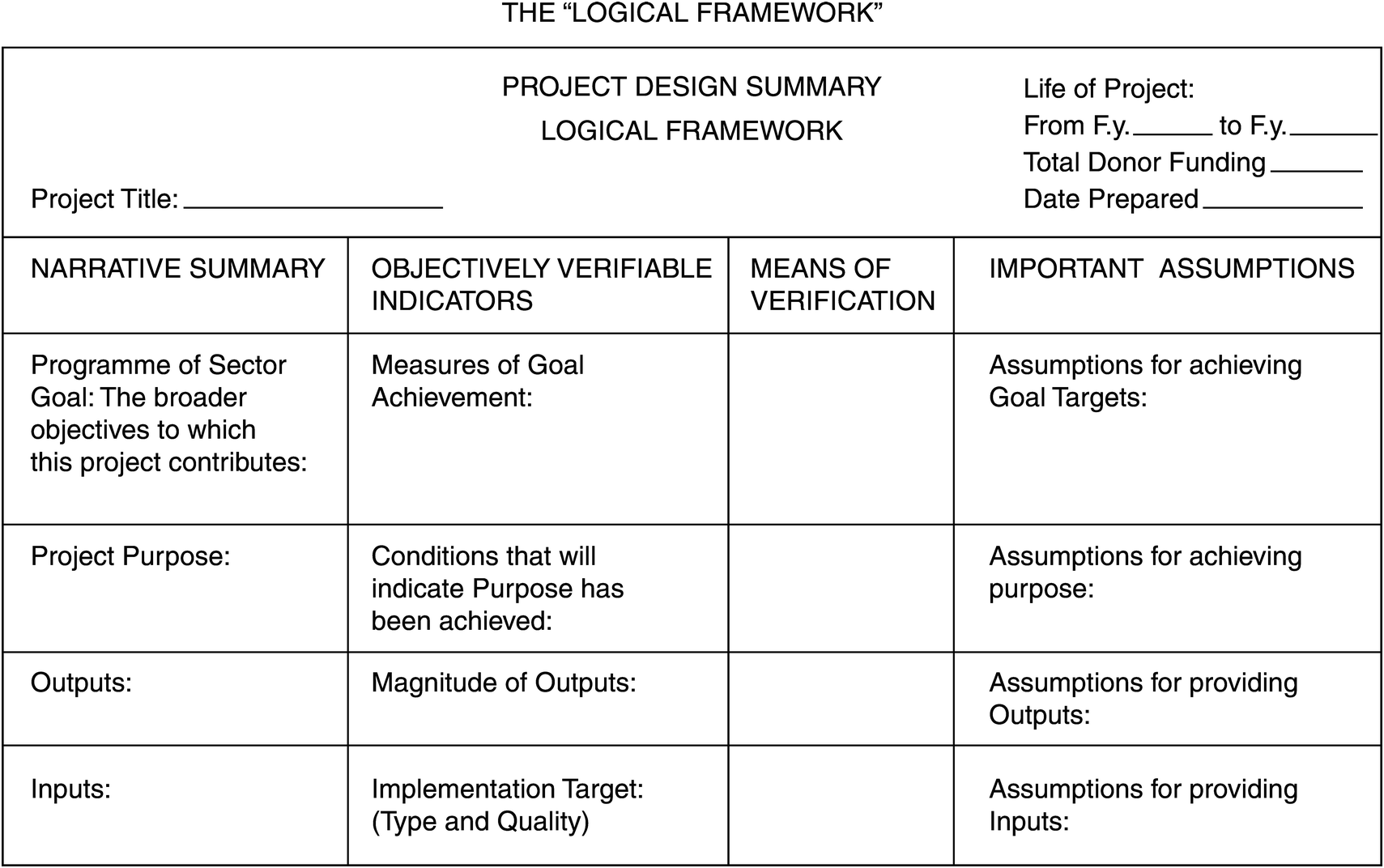

Back in 1969, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) had commissioned a group called Practical Concepts to develop the program design framework that became the LOGFRAME.13 Although results matrixes have evolved over time, this initial framework established many of their crucial elements. The LOGFRAME (Figure 8.1) encouraged development planners to focus on outputs rather than inputs, and required them to identify “objectively verifiable indicators,” the “means of verification” and the “important assumptions” for each step in the process. Within a few years of its development, thirty-five other aid agencies and NGOs had begun to use the LOGFRAME in their work.14

Figure 8.1 The LOGFRAME16

Two and a half decades later, as new public management thinking spread across the Western world, the US Government Performance and Results Act, which tied budgetary decisions to measurable results, was passed with bipartisan support and was soon applied to USAID.15 If anything, the pressure on development agencies was even more acute than other areas of government policy, since it was believed that financing for development was even less good value for public money than that spent on domestic programs. If the initial focus on the problem of results was a response to the perceived failure of the public sector, the later concern with development results was linked to the more specific belief that development aid in particular was inefficient. Yet, despite these considerable pressures, the move to results-based management was a contested one. In fact, Andrew Natsios notes that the USAID Administrator at the time, Brian Atwood, saw the performance-based legislation as contrary to the needs of his agency. Yet he ultimately decided to accept the lesser of two evils (the first being the abolition of the agency, proposed by conservative members of Congress), hoping that “he could prove to USAID’s adversaries that foreign aid works and could produce quantitatively measurable program results.”17

The World Bank also began to focus on results management in the 1990s, championing its spread to low- and middle-income countries. The Bank had a long history of focusing on public-sector reform in borrowing countries.18 By the late 1990s, its staff were focusing on its good governance agenda, convinced that institutional reform was vital for policy success. It was in this context that the staff involved in public sector management – now located within the poverty reduction and economic management (PREM) area – began to emphasize the adoption of new public management-inspired reforms in developing countries, including results-based measurement.19

The spread of these new public management-inspired ideas into development policy was not entirely smooth, however, for it encountered a second, somewhat different approach to evaluation – one that emphasized local knowledge and participation. Participatory approaches to project evaluation had existed for many years, particularly among NGOs, but became increasingly popular with the publication of Robert Chambers’ work on participatory rural appraisals (PRA) in the mid-1990s.20 PRAs were a more participatory version of the earlier Rapid Rural Appraisals (RRAs) which emphasized the cost-effectiveness and usefulness of project evaluations that relied on local knowledge (often through interviews) rather than more formal quantitative analyses.21 The chief difference of participatory evaluations was that they were to be driven by locals themselves, and organized around their concerns. The objective of participatory appraisals was not simply to extract information from local populations, but to empower them to identify their own needs and assess development programs’ success in meeting them.22 Here then was another strategy for measuring and evaluating the success of development programs, but one that focused on meeting poor people’s needs rather than on ensuring organizational efficiency.

Development organizations struggled with these tensions. At the World Bank, different units adopted different approaches to measurement and evaluation, with the PREM focusing on public-sector reform and public choice-inspired results management, while those involved in social development relied more on participatory approaches inspired by Chambers’ work.23 At the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), which introduced its first results-based management policy around the same time as USAID in the mid-1990s, there were also discussions about how to reconcile different approaches to measurement and evaluation.24 One 1996 CIDA paper made a careful distinction between top-down, donor-controlled management by results and a more bottom-up, indigenized management for results.25 While the first was often focused on more bureaucratic objectives such as reporting back to stakeholders, the second was designed to improve performance in the field. The authors noted that most CIDA policies and practices to that point had been dominated by the first of these approaches. While the paper’s authors supported results-based management in principle, they made a strong case for developing a more dynamic, even experimental approach which they felt was better suited to meeting CIDA’s increasing concern with institutional development.

Analysing early results-oriented approaches

Despite their differences, these earlier versions of measurement and evaluation had similarly ambitious objectives: to transform development governance by creating new kinds of facts, enrolling new participants, redistributing expert authority, and using productive power to constitute new, more proactive actors.

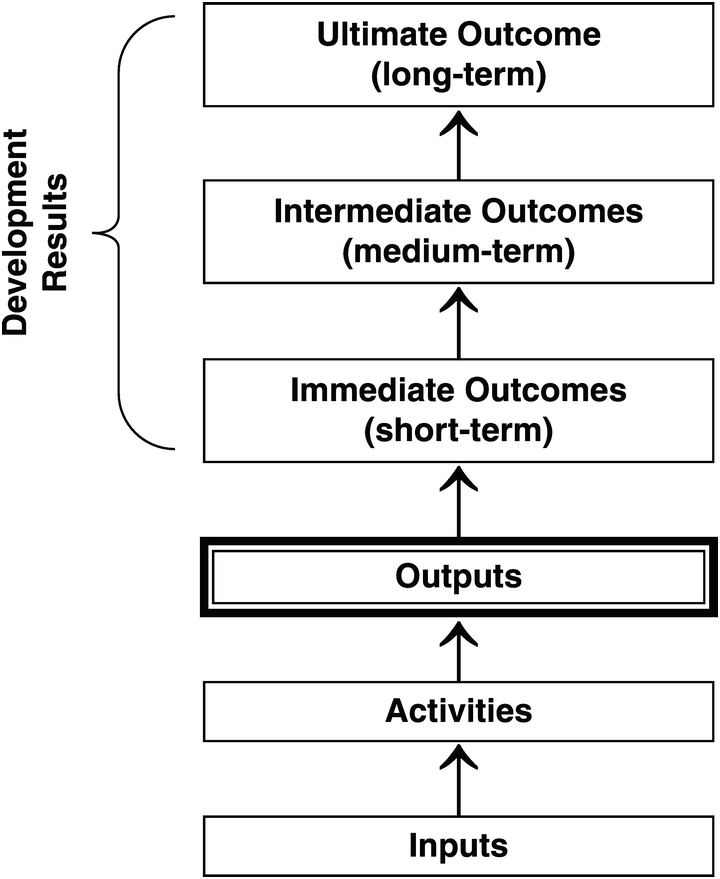

The New Zealand-inspired approach to results management required a new kind of counting and accounting to ensure that public sector managers had achieved the targets set out in their contracts. At the heart of results-based management is a particular kind of inscription: the causal chain, or logical framework, which seeks to create logical connections between inputs, outputs and outcomes (Figure 8.2).26 In creating such a framework, public sector or IO staff must develop a results chain that links each step in the policy process, effectively identifying causal relationships between a particular input (such as training more doctors), an expected output (more doctors in a region), and a range of desired outcomes (a healthier population). At each stage, it is also necessary to identify indicators that will allow for the measurement and monitoring of each step in the causal chain (e.g. counting the number of doctors). The objective of this system is to establish a direct link between bureaucrats’ actions and the outcomes that result, in order to make public-sector actors accountable for the services rendered (or not).

Figure 8.2 CIDA’s results chain28

PRAs also sought to create a new kind expertise using new techniques. Chambers sought to replace statistical techniques with participatory processes that produced their findings by talking to the local population. It took time for these new fact-producing techniques to be widely accepted; as Chambers notes, the earliest practitioners who used RRA-like techniques felt obliged to do more traditional, quantitative and time-consuming studies after the fact, in order to persuade development agencies that their results were credible.27 It was only over time, as Chambers’ ideas began to gain momentum, that the kinds of facts that RRAs and PRAs collected – interview data, stakeholders’ opinions, drawings and other kinds of non-verbal information – began to be viewed as authoritative.

Both policy approaches also sought to enrol new actors in their results-oriented techniques and, in doing so, to transform the culture of development organizations. In the case of the new public management-driven approach, the goal was to train borrowing-country bureaucrats to use the results chain in their own policy development. The PRAs sought to enrol local community actors in the processes of evaluating and refining development policy, and to change the way in which development professionals interacted with local actors. Both results approaches sought to involve new actors and transform them by changing the culture in which they operated. In both cases, the transformation that they sought to achieve in bureaucratic actors was quite profound: in the first case, bureaucrats were to become more entrepreneurial, driven by rational incentives rather than traditional notions of public service, more adaptive to change and accountable to their political masters. In the second, development agency staff were to renounce their efforts to control the evaluation process and act as facilitators for the voices of others. In both cases, a profound cultural transformation was the goal.

Of course, the forms of expertise that each kind of strategy sought to create and authorize, the actors they sought to enrol and the changes in culture that they sought to foster were quite different. Yet some initial points of contact did exist even in the infancy of these two result-oriented approaches; moreover, they were to begin to converge further as time went on and the results agenda came to dominate the global governance of development over the next decade.

Recent developments

The results-based measurement strategy initiated in the 1990s has gained significant new impetus over the past decade, as the idea of results has been enshrined in three key international agreements: the millennium development goals (MGDs) (2000), the Monterrey Consensus (2002) and the Paris Declaration (2005). As their name suggests, the MDGs establish concrete goals towards which the state signatories agree to work in order to reduce poverty. These goals are not only broadly defined, such as the goal of reducing extreme poverty and hunger, but are also broken down into more concrete targets, such as that of halving the proportion of people who suffer from hunger by 2015. Moreover, movement towards reaching each of these targets is measured through more specific indicators, such as the prevalence of underweight children.29 This kind of practice of linking measurable indicators to intermediate targets and longer-term goals is central to results-based strategies.

If the MDGs established a kind of preliminary methodology for measuring global results on poverty reduction, then the Monterrey Consensus articulated the rationale for integrating results-orientation as a key element of developing country public sector reform. It was at the Monterrey Conference on Financing Development that an agreement was reached on the principles that were to underpin the global governance of development aid: the key principle was mutual responsibility, whereby industrialized countries agreed to bring aid levels closer to the level needed to meet the MDGs in exchange for developing countries’ promise to take responsibility for developing “sound policies, good governance at all levels and the rule of law.”30 Three years later, when OECD countries agreed on the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, results-measurement and evaluation were seen as the central mechanism for achieving these better development outcomes.31

If advocates for results-based management in the 1980s justified this radical shift in public sector governance by claiming that big government had failed, those pushing for this more recent problematization of results have pointed to the failure of aid effectiveness. As Patrick Grasso, a member of the World Bank’s independent evaluation team, noted in a recent presentation, the Bank’s emphasis on results emerged in response to the “quality crisis” of the 1980s and 1990s as programs’ success rates declined precipitously.32 The World Bank President, Paul Wolfensohn, who was preoccupied with the institution’s declining success rates, reorganized the Operation Evaluation Department (OED) in the mid-1990s, leading to its identification of results-based management as one of its strategic objectives.33 The adoption of results-based management at the Bank and among aid agencies was thus driven in part by fear of increasing rates of policy failure and a desire to demonstrate tangible policy success to their critics. As Grasso notes, “[The] move to results focus and concentration on effectiveness means that evaluation matters more than ever,” not only for internal reasons, but also because of external pressures, as “[s]hareholders want to know whether they are getting ‘value for money.’”34 Aid agencies and IFIs now need to be able to show the effects of their expenditures in order to be able to sell their programs to their leaders and publics.

Who were the external and internal actors pushing for the results strategy? There is little doubt that the US Administration played a major role in demanding that all multilateral development banks including the World Bank be accountable for results.35 As Natsios notes, one of President Bush’s mantras was that his three priorities were “results, results, results.”36 Other countries also pushed for results measurement, although with somewhat different objectives in mind: the Nordic countries, for example, were interested in providing more output-based aid in the health sector,37 while Latin American countries were keen on assessing the impact of World Bank, IMF and donor policies.38 UK representatives were generally supportive of greater focus on results at the World Bank in the early 2000s. Yet they were careful about what was actually achievable in this regard, cautioning against being overly ambitious by seeking “the attribution of success to each agency or to individual projects”;39 and arguing that “we are focusing on managing ‘for’ rather than ‘by’ results,” echoing the earlier CIDA working paper discussed above.40

States were not the only key actors mobilizing behind the new results agenda. Internal advocates also played an important role in pushing for the results agenda, with not only Wolfensohn but also the Bank’s Chief Economist, François Bourgignon, playing leading roles.41 NGOs provided another source of support, although in a somewhat tangential way: critical NGOs like Eurodad and Oxfam had long argued that the IFIs should assess the impact of their policies, championing the Poverty and Social Impact Assessment (PSIA) tool at the Bank and the Fund.42 Although the goal and form of the PSIA is different from results-based management, its focus is nonetheless on measuring outcomes and relies on similar claims about the value of “evidence-based policy.” Although many of these same NGOs have since become more critical of the results agenda, their criticisms have been primarily focused on what kinds of results are being measured, rather than on the measurability of results more generally.43 Finally, the Washington-based think tank, the Center for Global Development (CGD) has played a crucial role in moving ahead the results agenda through its development and advocacy for a “cash on delivery” (COD) approach that links financing with measurable outcomes.44 The COD approach has caught on at the World Bank, and the CGD has been very active in training Bank staff in this policy.45

Donors get more quantitative

As I discussed earlier in this chapter, donor agencies were among the first to integrate results-based measurement and evaluation techniques into their policies as part of broad-based public-sector reforms. Yet in many of these cases, the market-based approach to results was an uncomfortable fit for organizations seeking to achieve more complex, process-oriented and long-term reforms such as institutional development. These organizations were also interested in using more participatory evaluation techniques that were sometimes at odds with the techniques or objectives of the public-choice approaches. The agencies’ response in many cases was to try to find a compromise between the donor and recipient-driven approaches and to create more space for flexibility within the results-framework. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, DFID, for example, relied on more qualitative indicators that better captured the complexities on the ground.46 These adaptive strategies helped resolve the tensions in results-based management techniques between the goals of reporting (to the donor government) and of improving policies (for the recipient community). Yet they did so by reducing the clarity of reporting, since numbers were often replaced by more complex accounts of successes and failures.

This particular resolution of the tensions in results management did not, however, provide the kind of shot in the arm to the legitimacy of development governance that key actors had hoped for. Politicians did not just want results, but measurable ones, so that they could take them back to their constituencies and explain why the money had been spent. In 2004, the Bush Administration was the first to translate this desire for quantifiable results into a new kind of development organization: the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). All of this agency’s loans were to be tied to borrowers achieving a passing score in several quantitative indicators, including indicators on governance. The assistance in turn was to be linked to clear objectives, and results were to be regularly reported to Congress. While the agency ultimately had to fudge things a little (after almost no country qualified for financing), and created a new category of threshold programs designed to help countries meet the minimum targets, it had nonetheless dared to do what no other agency had: to develop quantitative governance-based criteria for aid. In the words of one former advisor to the DFID Minister, Claire Short, the MCC’s willingness to create hard quantitative criteria was “the elephant in the room” that all of the other agencies tried to ignore, but could not.47 Many other governments also dearly wanted to be able to show results and justify lending through the clarity of numbers.

While no other agency has been willing to tie its aid so strictly to quantitative measures of country results, many have moved towards more rigid kinds of results-based measurement. Both CIDA and DFID, which had been more cautious and conflicted in their application of measurement and evaluation in the 1990s, were asked by their respective ministers to impose a stricter kind of results-based management. At CIDA, a new results-based management policy statement was issued in 2008 that updated the policy adopted twelve years earlier. This new policy makes it very clear that the central objectives of results management are entirely focused on bureaucratic objectives: better “planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation,” together with more transparent reporting to its key stakeholders – Parliament and the Canadian public.48 Just six years before, the organization was still struggling with the complexities involved in applying more traditional results-based management approaches to development programs.49 By 2008, however, the difficult debates that had earlier preoccupied the organization had gone underground.50 What took their place was a very straightforward form of top-down results management, or what CIDA staff earlier called a “donor-oriented” rather than “field-oriented” approach.51

DFID was similarly pressured to provide clearer data on results to its political masters, particularly in the context of growing pressure on government budgets.52 As the Overseas Development Institute’s David Booth noted in an interview conducted before the 2010 election, aid has come to be seen by both Labour and Conservatives as a vote-winner – but only if claims about aid making a difference are verifiable.53 DFID’s 2007 Results Action Plan begins with a mea culpa of sorts:

DFID needs to make a step change in our use of information. We need to use evidence more effectively in order to ensure we are achieving the maximum impact from our development assistance. We also need to be able to demonstrate its effectiveness more clearly.54

Demonstrating effectiveness, moreover, means basing more development program decisions on quantitative information: this is the number one priority of the reforms proposed in the action plan. In fact, as Booth noted, “senior managers at DFID headquarters adopted a ‘results orientation’ that placed a strong emphasis on monitoring quantifiable final outcomes, which put a new kind of pressure on program design and delivery in country offices.”55 The Action Plan is also quite frank about what its authors believe were the reasons for the decline in the use of quantitative information, suggesting that “as our work has moved progressively away from discrete project investments, we have made less use of tools such as cost-benefit analysis.”56 As DFID moved from projects to program-based, longer-term and more country-owned support, they also lost the ability to easily link causes and effects, and to compare costs and benefits. Decisions were thus no longer easily linked to quantitative evidence and it became more difficult to communicate the results of development assistance to the public. This new results action plan seeks to rectify these perceived failures. As I will discuss further in this book’s Conclusion, this attention to “hard” results has only gained ground over the past few years, not only in the UK but also in several other key donor countries with conservative governments, including Canada and the Netherlands.

The World Bank’s recent initiatives

In the past decade, the World Bank has also “mainstreamed” results-based measurement. Before this shift occurred, the results-based approaches of PREM’s public-sector teams and the social development groups were not well integrated into the core of Bank operations. Integration first began in the context of the organization’s development of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) together with the IMF, in 1999.57 The PRSP was supposed to include general objectives and more specific targets and indicators that could then be monitored by both the borrowing government and the lending institutions. The idea of results was thus integrated into the PRSP: countries were asked to develop a detailed matrix prioritizing their poverty objectives and outlining the longer-term and shorter-term results that they were seeking to achieve, as well as how they would achieve them. The PRSP thus sought to combine top-down and bottom-up forms of results management, by linking participatory input to more bureaucratic forms of measurement and evaluation.

The results-orientation of PRSPs has had several important effects on development practice for both borrowers and lenders. As I will discuss further in the Conclusion, reviews of the early PRSPs indicated that the prioritization and results orientation of many documents were uneven.58 This has lead to increasing pressure on countries to develop more results-oriented poverty reduction strategies. Since the same reviews made it clear that many countries do not have the capacity to produce the necessary statistics, nor to integrate results management into their public service, this has also increased emphasis on institutional capacity building and on results-based public-sector reform more generally.

Donors have also pushed for results-based management at the country level, particularly through their role in the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA). IDA funds are provided to low-income countries (LICs) in the form of long-term interest-free loans and grants, and are made possible through contributions (known as fund replenishments) from industrialized states. During the negotiations over IDA13 in 2002, the thirty-nine donors agreed that their support was contingent on borrowers’ being able to demonstrate specific results. Outcome indicators were developed to track progress towards achieving targets in areas such as health and private sector development.59 Ultimately, the Bank created a system of “performance based allocation” (PBA) that linked the level of IDA funding that each country could receive to a score that was a combination of a country’s demonstration of need and its performance as determined through the country policy and institutional assessments indicators (or CPIA – as discussed in Chapters 6 and 7).60 Three years later, IDA14 took this results-oriented approach one step further and developed a Results Measurement System at the Bank that monitors broad country-level outcomes, IDA’s contribution to those country outcomes and changes in statistical capacity in LICs.

Most recently, the Bank has proposed yet another results-based instrument: the Program for Results (P4R) lending. The P4R, which was adopted by the Board in 2012, is designed to provide a third form of World Bank lending, somewhere between investment lending (for specific projects) and development policy lending (for broader government reforms). Bank management seeks to use this lending instrument to directly tie the disbursements of funds to the achievement of agreed performance indicators, such as a percentage reduction in the mortality rates of children under five, or the length of time that it takes to start a new business.61 One of the primary goals of the Bank’s new results-oriented programs is to focus on building country capacity – particularly their capacity for results measurement, fiduciary oversight and risk management (all the technical capacities needed for a results-based approach).62 Interestingly, one of the main arguments presented in the Bank’s Revised Concept Note in favour of P4R is the fact that other already existing lending instruments cannot be fully tied to results; the document’s authors make no attempt to justify the usefulness of focusing on results per se, but rather seek to explain why this particular instrument is needed in order to allow a results focus. Results management is thus becoming black-boxed as an operational concept in development assistance: a general good that needs no justification.

Analysing governance factors

The path towards the current quantitative approach to results-based measurement and management has therefore not been a straight line from public-choice textbooks to the current action plans and results strategies. Instead, it was only after a decade of trying to modify the stricter forms of results-based management to suit the complexities and uncertainties of development programs, to reconcile it with the goals of country ownership and to integrate some of the insights of participatory evaluation, that we have now seen a turn to a more donor-driven kind of measurement strategy. In this final section, I will trace the ways in which the results strategy involves significant changes to the factors of governance.

I have suggested throughout this chapter that results-based management is above all about creating a new kind of knowledge. For if one wants to manage for and by results, one also needs to know those results; this in turn means determining what results are desirable and how to measure them, and deciding what constitutes a result in the first place. This process of creating new kinds of facts called indicators, targets and results is as much material as it is ideational: it involves a new set of measurement and inscription techniques to make them possible. All of these elements – the starting point, the objectives and the indicators – must be translated into facts, of either quantitative or qualitative kind. They have to be made into paper – or more precisely into tables, graphs, charts or, best of all, numbers. Of course, development practices have always had to translate complex information into various kinds of inscriptions – chiefly reports. What is different about this kind of inscription is its attempt to make this new slippery object – the result – visible, and to do so in a way that manufactures clear causal connections between specific policy actions on the one hand and a number of concrete development outcomes on the other. Although the promised results appear to be very concrete, they are in fact based on a set of highly symbolic practices that make the links between action and outcome visible.

The development of these new measurement and inscription techniques has concrete effects on how policy is conducted. Results-based measurement involves a shift from focusing on inputs and outputs to emphasizing results. Yet it is also a shift from processes to outcomes, as many of the critics of results-based management have pointed out.63 It is easier to count the number of women who show up for participatory evaluation sessions than to determine whether their voices carried weight.64 The focus on results – and more specifically on results as translated into quantifiable indicators that can be compared and aggregated into appealing reports – thus has specific costs and consequences for the ways in which development is conceptualized and practised.

The contemporary results strategy also relies on a second set of techniques that seek to produce new knowledge through the solicitation of public feedback via various technologies of community. This is where the LOGFRAME meets some of the ideals of participatory development. These techniques seek to connect policymakers to particular publics through the logics of demand and accountability. In some cases, results-based approaches involve direct participation by local groups affected by development policies – either to identify desired outcomes or to evaluate success in meeting them. The PRSP is the most obvious example of this linking of participation and results, since it was designed to funnel broad-based consultation processes into a set of objectives that can be prioritized and set out in a results matrix.65

The publication of results links these two techniques through the same kind of symbolic logic that we saw in the strategies of ownership, standardization and risk management: result scorecards make visible the complex (and often highly problematic) links between policy action and outcome, and in the process signal better or worse performance. Such symbolic practices are also performative: the goal here, as in the other strategies, is not only to rank performance but also to mobilize governments and NGOs to pay attention to the results and respond accordingly.

These techniques thus seek to enrol new actors and ultimately to transform them. The first and most obvious group of actors to be enrolled is bureaucratic staff, in both donor organizations and recipient governments. Results-based measurement involves subjecting the calculators themselves – development organization staff – to a new kind of institutional culture. New public management advocates are quite explicit about the fact that one of their central goals is to create a “results culture” in which staff will change not only their behaviour but also their sense of identity as they become more entrepreneurial in their effort to achieve results. One senior World Bank staff member who has run workshops on results measurement suggested that a results focus changes policy, but not in a mechanical way: instead, the process of thinking about results actually changes people’s mind-sets.66

These workshops and training programs do not only target IFI and donor government staff, but are also oriented towards developing and emerging market bureaucrats. This effort has been underway for a good number of years, in the context of IFI and donor pressures for public-sector reform. Yet it is only more recently that developing public-sectors statistical capacity has become a key priority for development efforts – as it is in the Bank’s proposed P4R instrument. The goal is ultimately to train people to view their activities through the lens of results measurement, identifying the objective, mechanisms and indicators on their own. Results-based management thus seeks not only to make up facts, but also to “make up people” – transforming the bureaucratic hack of old into a new kind of subject capable of certain kinds of calculation and responsible for his or her specific policy effects.67

At the other end of this measurement process, however, these techniques seek to constitute and enrol another kind of new actor in governance activities: the public. This public not only includes the individuals who participate in certain forms of evaluation and measurement, but also refers to a more abstract public invoked by both public choice theorists and development policy documents: the public that demands accountability in the form of visible, measurable results. This public exists in both donor and borrower countries, and plays a crucial role (at least in theory) in demanding better and more clearly demonstrated results. Results-based management thus seeks to involve the public in governing development by creating the kinds of facts that they need to hold donor and borrowing governments to account. Results-based management techniques, like the good governance reforms and risk management strategies that I discussed in earlier chapters, are to be based not just on IO and donor supply but also on country-level demand. Results-based measurement thus seeks to redistribute some of the authority for governing development to domestic government bureaucrats and the wider population through their capacity to hold the government to account for policy results.

These new techniques of creating new kinds of facts, reshaping institutional cultures and encouraging certain kinds of public participation all involve particular forms of power. Some of these are highly exclusionary: performance-based allocation is probably the clearest example of this kind of power, creating as a does a new kind of ex-ante conditionality. The performance-based allocations use CPIA measurements of country performance to determine how much aid a country can receive. A poor score can mean a 40 per cent drop in funding for a country desperately in need of aid.68 With the development of results-based P4R lending at the World Bank, more financing will be tied to performance. No matter how it is dressed up, this is a highly exclusive kind of power. Yet even where power appears relatively obvious, as it is in this case, it is also quite indirect. Although results seem to be a very direct object to target, they are always several times removed from those seeking to attain them, and may not be entirely within their control. The very fact of focusing on results and outcomes as the basis for allocating aid (e.g. number of days it takes to open a business), rather than on specific policies or efforts (e.g. passing legislation to facilitate new business start-ups), means that it is much harder to determine responsibility for a country’s improving or worsening score; the ultimate results may be caused by local inefficiency, cultures of non-compliance, broader economic changes, or any number of other factors not within the direct control of the government. The effect of this kind of performance-based financing is rather similar to the informalization of conditionality that I discussed in Chapter 5: even though the conditions are explicit in this case, it is not at all clear how to ensure compliance.

Why would donors and IOs create conditions without making it clear how to go about complying with them? Why should A tell B what they should achieve without telling them how to do so? Clearly, the object of power in this case is not simply the achieving of the result, but the process of getting there: of having to figure out how to obtain it. By rewarding and punishing specific results, the hope is to encourage a change in the behaviour of those pursuing them. This is a kind of productive power that encourages a new kind of responsibility in developing countries.69 Borrowing governments are thus lent a certain degree of authority in determining how to obtain the outcomes, but are not given the right to determine what those outcomes should be. Of course, it is not just borrowing governments who are the objects of this kind of productive power. Organizational staff are also key targets: the goal of results management is quite explicitly to transform bureaucratic cultures both within developing countries and in the agencies that lend to them.

Perhaps most interesting of all, however, are the transformations to expert and popular authority enabled by results-based management techniques. These new techniques are designed to re-found the expert authority of international and domestic development agencies by creating a new kind of fact that promises to show the definitive links between policy actions and their effects. This manoeuvre is absolutely essential for organizations whose internal cultures and external legitimacy have always rested on claims to expertise. Less obvious, but just as important, is the way in which the results strategy also seeks to redistribute authority to a wider group of actors, including the general public, and, in the process, to bolster lenders’ expert authority with claims to popular legitimacy. The public choice theory that underpins results-based management has always involved a particular (narrow) conception of the public: as an aggregation of rational maximizing individuals who demand value for money from their civil service.70 The gamble then is that the publics in both borrowing and donor countries will see their needs and priorities reflected in development targets and results, and thus grant the organizations the legitimacy to continue their work.

A more provisional style of governance

I have argued throughout this book that the various changes that we are currently witnessing in how development is financed add up to a shift towards a more provisional form of governance – a kind of governance that is more proactive in its engagement with the future, often indirect in its relationship with its object, reliant on increasingly symbolic techniques, and above all aware of and evasive in the face of the possibility of failure. If we believe what many of the advocates of the results agenda say about it, we would have to conclude that results measurement is the least provisional of these new strategies of governance. After all, it promises direct and transparent access to the truth about which development policies succeed and which fail in delivering concrete results. Yet, as my examination of the results strategy in this chapter has shown, the way that results measurement works is far more complex – and provisional – than this straightforward account suggests.

Although those who advocate results-based management focus on the end-point of development finance – its outcomes – they do so in order to change the way that practitioners approach any project, by changing the way that they conceptualize and plan the work at hand. This is a highly proactive form of governance that seeks to inculcate a particular kind of awareness of the future. Whereas in the past, measurement and evaluation was more episodic and often relegated to specialized units, it has now become all-pervasive in space and time. Although some bureaucratic actors and units remain evaluation specialists, all are required to engage in the process of identifying, anticipating and measuring results. Results measurement is thus an indirect form of governance, focusing on gradually altering bureaucratic measurement cultures in order to change their actions over the longer term. When the bureaucracies targeted are in LICs, this effort to transform the culture of development finance becomes a very potent but indirect form of power.

Results measurement is also a strategy that is preoccupied with the problem of failure. In recent years, as development agencies and IFIs have made it a top priority, they have done so in order to respond to their stakeholders’ concerns about past failures of aid effectiveness. At the same time, the strategy’s strong ties to public-choice theory and its suspicion of the public sector mean that it is always haunted by an awareness of the possibility of yet more failures. It is hard to ignore the underlying assumption that if it is not possible to show visible results, then the policy is just another public-sector failure. Hence the importance of making any successes visible by clearly demonstrating the actual results of particular organizations’ actions.

Yet in practice, as I will discuss at greater length in the next chapter, the results measurement strategy has encountered some of its own limits and failures. Although the pressure to adopt results management is immense, there is nonetheless significant resistance within many agencies and IFIs – with the IMF being the most notable example. Underlying much of this resistance is an awareness of the fragility of many of the expert claims on which results management is based. This fragility in turn is linked in large measure to the symbolic and highly constructed character of the key inscriptions at the heart of the strategy. In one sense, results are very real: they may involve a certain number of early-childhood deaths, or a particular level of inflation. Yet results are also symbolic insofar as they signal a kind of achievement based on a claim that this particular set of deaths or level of prices is a direct result of specific lender actions – causal links that are often highly questionable given the multitude of lenders, programs and exogenous factors affecting such complex outcomes. We should therefore not be too surprised that there is a growing debate about whether the new “facts” that results strategies promise to create have any validity: a growing number of institutional staff and commentators are questioning the plausibility of efforts to establish causality and attribution – drawing a line between policy input and outcome.71 Thus, ironically, even as results measurement appears to be getting more definitive and factual, it is actually becoming more fictitious and symbolic, as claims about results achieved slip further away from reality.

Paradoxically, these methodological and epistemological weaknesses in the results strategy provide an opportunity of sorts for institutional actors – creating a certain amount of fuzziness in the results matrixes and therefore some room to hedge against failure. Despite renewed emphasis on hard numbers, because of their often-symbolic character, the careful identification of indicators and elaboration of results chains are subject to a certain amount of fudging, as both borrowers and lenders have significant incentives and opportunities to “game” the numbers and demonstrate positive results. This is particularly the case at the World Bank, where the incentive structure remains focused on the disbursement of as many dollars as possible, regardless of results.72 Organizations have clear incentives to publish positive results and can often find ways of making less than perfect results appear satisfactory. For example, as Stephen Brown points out, the Canadian government’s document on their aid commitments indicates that everything is “on target” even when the evidence suggests that results have slipped in several categories.73

However ingenious the attempts to game the system may be, and however ubiquitous the call for results, the strategy remains fragile and subject to considerable tensions. The wager that it is based on – that the demonstration of measurable results will re-establish IFI and donor authority – is thus far from certain to pay off. Yet all of the various strategies’ efforts to bolster institutional authority hinge to some extent on their promise of providing measureable results. The uncertain destiny of the results agenda thus raises important questions about the direction and sustainability of the new more provisional logic of global economic governance, as I will discuss in the Conclusion.