8.1 Introduction

Leaders and pioneers are widely seen as agents of change. Such actors are of central importance for climate change mitigation and adaptation. We define pioneers as being ‘ahead of the troops or the pack’ while carrying out ‘activities which, depending on the circumstances and events “in the field”, may or may not help others to follow’ (Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017: 952–953). Leaders, on the other hand, have ‘the explicit aim of leading others, and, if necessary, to push others in a follower position’ (Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017: 953). In other words, leaders usually actively seek to attract followers (Burns, Reference Burns1978, Reference Burns2003; Helms, Reference Helms2012; Torney Reference Torney2015), while pioneers normally focus on domestic or internal activities without paying much attention to attracting followers, although they may unintentionally set an example for others.

The literature on leaders and pioneers in environmental and climate policy initially focused primarily on states (e.g. Young, Reference Young1991; Underdal, Reference Underdal and Zartman1994; Andersen and Liefferink, Reference Andersen and Liefferink1997; Jänicke and Weidner, Reference Jänicke and Weidner1997). However, non-state actors have increasingly also been identified as capable of exhibiting climate leadership and pioneership (e.g. Wurzel and Liefferink, 2017). International climate change governance has traditionally been analysed as taking place within multilevel governance (MLG) structures, within which leaders and pioneers play a central role (e.g. Grubb and Gupta, Reference Grubb, Gupta, Gupta and Grubb2000; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Huitema, van Asselt, Rayner and Berkhout2010; Wurzel and Connelly, Reference Wurzel and Connelly2011). However, especially since the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which largely abandoned the 1997 Kyoto Protocol’s top-down ‘targets-and-timetables’ approach in favour of a bottom-up approach with national pledges (i.e. nationally determined contributions; see Chapter 2), international climate governance appears to have become more polycentric (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Huitema and Hildén2015; Oberthür, Reference Oberthür2016; see also Chapter 1). This chapter therefore assesses to what degree, if any, climate leaders and pioneers can play a central role not only within MLG structures but also under conditions of polycentric climate governance.

As we explain in more detail in what follows, under conditions of polycentricity, a potentially very large ‘universe’ of actors can in principle act as leaders or pioneers. According to Elinor Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010: 552), ‘(p)olycentric systems are characterized by multiple governing authorities at different scales rather than a monocentric unit … Each unit within a polycentric system exercises considerable independence to make norms and rules within a specific domain.’ However, while polycentricity and monocentricity, which constitute opposite poles on the governance dimension, are useful heuristic analytical terms, they are rarely found (at least in their pure form) in the highly interdependent pluralistic liberal democratic states which are the main focus of this chapter. Whereas in MLG structures leaders or pioneers may be limited by hierarchical relations and restrictive rules, each ‘unit within a polycentric system’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010: 552) can have its own leaders and pioneers. Pushed to its extreme, polycentricity potentially enables virtually any conceivable actor within a particular unit of governance to become a leader or pioneer. At the same time, polycentricity may limit the effect of leaders and pioneers to the relatively independent unit in which they function.

In this chapter, we first discuss the specific features of leadership and pioneership under conditions of polycentricity at a conceptual level. Drawing on the existing literature and a wide range of examples, we then offer a systematic assessment of various types of actors employing different types of leadership and pioneership in polycentric climate governance.

8.2 Polycentricity, Leadership and Pioneership

Polycentricity potentially offers seemingly endless opportunities for leadership and pioneership. At the same time, the relative autonomy of polycentric decision-making centres (e.g. Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012) may severely limit the range of possible followers. If we view ‘a family, a firm [or] a local government’ as a fairly independent unit within a polycentric system (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010: 552), it cannot be automatically assumed that its activities attract followers from outside this unit. Hence, at first sight, pioneership seems more likely than leadership to occur under conditions of polycentricity. A closer look at two basic conceptual features of polycentricity and their links to MLG, which constitutes another widely used concept of multicentred decision-making, may provide a more nuanced picture (see also Chapter 1).

First, the concept of polycentricity is built on a functionalist logic. Vincent and Elinor Ostrom and their collaborators developed the idea of polycentricity around various specialised agencies providing specific public services (e.g. water supply or policing) in local governments in the United States (Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren, Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961). In Ostrom’s definition, polycentric units ‘exercise considerable independence … within a specific domain’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010: 552; emphasis added) in which they perform specific functions or deliver specific services (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 241).

Second, polycentricity is a multilevel phenomenon. According to Aligica and Tarko (Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 241), the Ostroms ‘hammered the crucial fact that the optimal scale of production is not the same for all urban public goods and services’. Hence, ‘the existence of multiple agencies interacting and overlapping … is the result of the fact that different services require a different scale’ (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 241). This insight can be linked to the normative principle of subsidiarity which states that decisions should be taken at the lowest possible level of governance. Subsidiarity also plays a role in the governance of federal and quasi-federal systems such as the European Union (EU) (see also Chapter 1).

The functional and scale-focused character of polycentricity resembles key features of MLG. This is especially the case for Hooghe and Marks’ (Reference Hooghe and Marks2003) analytical distinction between Type I and Type II MLG. Type I refers to nested, non-intersecting, general-purpose jurisdictions, i.e. the ‘systemic’ hierarchy of territorial units – municipalities, regions, states, international organisations – which is reflected in the formal governance structure of states as well as the EU. Type II refers to flexible, task-specific, overlapping jurisdictions and shows strong resemblance with polycentricity. Rayner and Jordan (Reference Rayner and Jordan2013: 75) even equate polycentricity with MLG when stating ‘polycentric or, in EU parlance, multilevel governance’.

Comparing polycentricity to MLG Type II helps to demonstrate that polycentricity and monocentricity are actually related and may be seen as ideal-typical opposite poles of the same analytical dimension. This insight can be traced to the writings of both MLG and polycentricity scholars. Hooghe and Marks (Reference Hooghe and Marks2003) have argued that the ‘systemic’ institutions of MLG Type I often help to provide the legal framework or the financial basis for functional Type II activities. In their view, ‘Type II governance is generally embedded in Type I governance’ (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2003: 238). Rayner and Jordan (Reference Rayner and Jordan2013: 77) note that polycentricity and monocentricity can be interconnected in various ways, as occurs, for instance, in the EU. This is also recognised by Aligica and Tarko (Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 248), who point to the ‘unstable coexistence’ of polycentricity and monocentricity. They acknowledge that different polycentric systems may be laterally related (e.g. the market and the legal system) and that polycentric and monocentric systems may be nested, not least when it comes to the provision of shared, overarching rules which are essential for the functioning of a polycentric system (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 255–256). Ostrom et al. (Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961) also refer to central mechanisms to resolve conflicts under conditions of polycentricity. In addition, several inherent weaknesses of polycentric systems that are flagged up by Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010, Reference Ostrom2012), including the risk of fragmentation, inconsistent policies, coordination problems and free-riding, could arguably be countered by establishing links to MLG Type I arrangements. Thus, Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010: 550) stresses that developing long-term solutions to complex problems (such as climate change) in fact requires both hierarchical and decentralised efforts. Homsy and Warner’s (Reference Homsy and Warner2015) study of sustainability policies in approximately 1,500 municipalities across the United States goes further by arguing that municipalities working in an MLG framework supportive of local sustainability action perform better than others under polycentric governance conditions. This notably involves the provision of incentives, redistributive mechanisms, expertise and technical assistance, as well as a favourable general political atmosphere by the state (i.e. MLG Type I) government. Thus, while the ‘pure’ forms of polycentricity and monocentricity are useful heuristic devices, at least in pluralistic democratic states they tend to be found in mixed forms.

The discussion so far makes three things clear. First, polycentric leadership/pioneership is likely to take place primarily within relatively small, often functionally differentiated domains such as a water district, a school, a branch of industry or a product chain (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010: 552). This implies that the ways in which leadership/pioneership can be exerted may differ depending on the relationships prevalent between actors within a particular functional context. In the next section, we explore in more detail the relevance of different types of leadership for different categories of actors in polycentric climate governance.

Second, the functional confines of polycentric leadership/pioneership may lead one to assume that the ambition and possible impact of polycentric leadership/pioneership are likely to remain limited to a small, functionally determined environment. This would strongly curtail the opportunities for attracting followers and thus put the focus on pioneership rather than leadership under conditions of polycentricity. However, the foregoing discussion suggested that polycentric systems actually maintain various relations with other (polycentric) systems outside their own relatively self-contained functional environment.

Third, the observation of polycentric (or MLG Type II arrangements) being embedded, at least in certain respects, in MLG Type I governance leaves open the possibility of some degree of leadership ‘from above’ (compare with Chapter 4, which argues that monocentric institutions remain important for safeguarding democratic control in systems with increasingly polycentric characteristics). For example, Homsy and Warner (Reference Homsy and Warner2015) found that active US states exerted leadership vis-à-vis municipalities within their territories by providing incentives, expertise, etc. Within the context of the German energy transition, there is strong empirical evidence of the federal government’s key role in creating favourable conditions for local initiatives (Ehnert et al., Reference Ehnert, Borgström, Gorissen, Kern and Maschmeyer2016; Jänicke, Reference Jänicke, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017). The Chinese National Development and Reform Commission in 2010 initiated a project that encouraged five provinces and eight cities to undertake pilot projects in order to demonstrate the feasibility of low-carbon development plans and renewable energy in urban areas (Li, Reference Li, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017: 264).

8.3 Types of Leadership and Pioneership in Polycentric Climate Governance

As stated earlier, the analytical concepts of leaders and pioneers which are rooted in the international relations and comparative politics literature were originally developed for states (Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017). The distinction between leaders and pioneers builds on the observation that states may have different internal and external ‘faces’, i.e. leaders and pioneers may foster internal and external ambitions to different degrees. We argue that this logic also applies to non-state actors in polycentric (and MLG) governance structures.

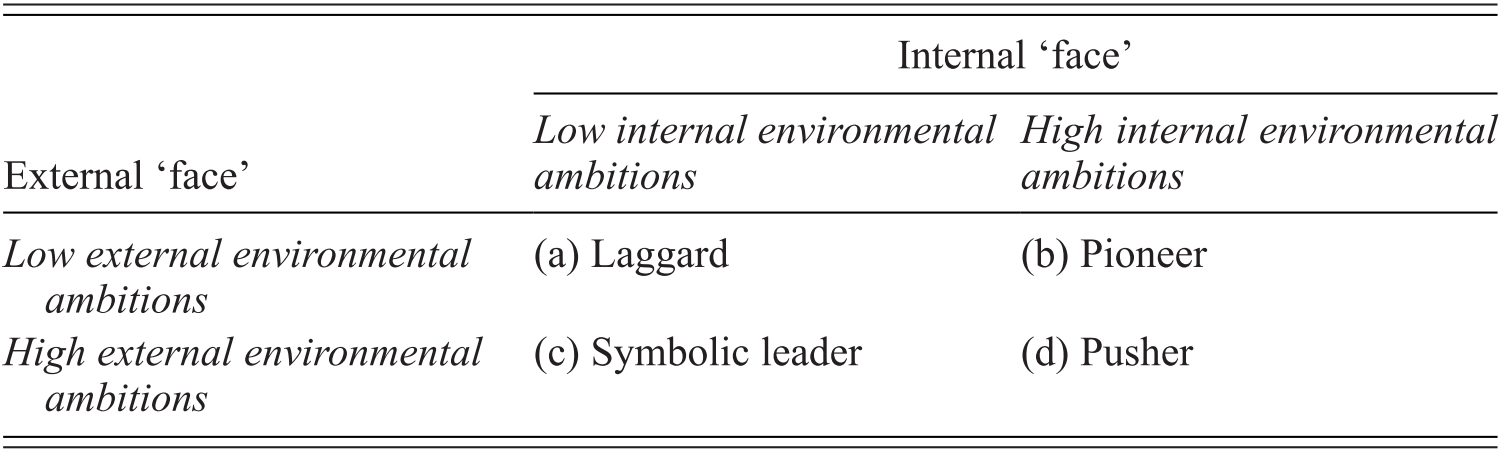

Table 8.1 shows the four ideal-typical positions that result from combining low versus high internal ambitions and low versus high external ambitions.

Table 8.1 Ambitions and positions of leaders and pioneers

| External ‘face’ | Internal ‘face’ | |

|---|---|---|

| Low internal environmental ambitions | High internal environmental ambitions | |

| Low external environmental ambitions | (a) Laggard | (b) Pioneer |

| High external environmental ambitions | (c) Symbolic leader | (d) Pusher |

An actor pursuing high internal and low external ambitions (cell b) adopts demanding policies for internal (or domestic) reasons without explicitly trying to attract followers. Such an actor can be defined as a pioneer. Symbolic leaders (cell c) and pushers (cell d) both have high external ambitions and thus offer leadership. However, while symbolic leaders combine high external ambitions with low internal ambitions, pushers pursue both high external and internal ambitions. Finally, laggards exhibit low internal and external ambitions (cell a).

The distinction between the internal and the external ‘face’ of a state can easily be applied to other governmental actors such as regions, provinces, cities and agencies, which all have internal policies while also maintaining ‘external’ relations. Importantly, the distinction between internal and external ambitions also applies to non-state actors. Internal ambitions may refer to, for example, production methods of firms or farmers, to purchasing policies of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or to consumption choices of individual citizens. External ambitions refer to their willingness to push or to set an example for other firms, consumers, etc. Consequently, the different positions set out in Table 8.1 can also be applied to non-state actors. An individual using public transport for environmental reasons without trying to convince others to abandon their cars may be characterised as a pioneer. The same applies to a citizen’s initiative producing wind energy primarily for their own use. Classic NGOs such as Friends of the Earth or Greenpeace, on the other hand, derive their very existence from high external ambitions. Their internal ‘face’ is less important, although in view of their credibility they are usually expected to act as pushers rather than symbolic leaders.

For market actors, Dupuis and Schweizer (Reference Dupuis and Schweizer2016) have pointed out that a firm with high internal ambitions logically also has a strong interest in realising these ambitions externally by keeping competitors at bay while profiling itself as the only actor of its kind in a particular market. In other words, such a firm wants to gain or maintain a competitive advantage or possibly even a monopoly position. In the early 2010s, the Dutch start-up Niaga developed a new method for producing a fully recyclable carpet using 90 per cent less energy than a product made following conventional production methods. As soon as the method was operational, some large carpet producers unsurprisingly attempted to acquire the exclusive right for applying the method (van der Steen, Reference van der Steen2017). It would be difficult to imagine a firm spending money on ‘measures to protect the climate without attempting to reap the potential benefits in terms of image and influence over consumers’ (Dupuis and Schweizer, Reference Dupuis and Schweizer2016: 5). From a company’s point of view, being a pioneer (as defined earlier, i.e. having only high internal ambitions) would constitute an unlikely form of altruistic behaviour, which is likely to be found only among not-for-profit organisations. What, as far as market actors are concerned, ‘truly distinguishes pushers from pioneers is their involvement in politics … Pushers’ external polic[ies] do not only target consumers, but they also lobby the state in order to enshrine their own norms and techniques of [greenhouse gas] reductions into formal legislation’ (Dupuis and Schweizer, Reference Dupuis and Schweizer2016: 5).

Leaders and pioneers can have an impact on other actors in polycentric (and MLG) governance structures in many different ways. They can, for instance, exert pressure on potential followers, spread new ideas or scientific insights or just offer a good example for others to follow. They can thus help to spread or upscale innovations. To assess these roles in a more systematic manner, we put forward an analytical distinction of different types of leadership that builds in particular on Oran Young’s seminal work on leadership in international regime formation (Young, Reference Young1991; see also Wurzel and Connelly, Reference Wurzel and Connelly2011; Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink, Reference Wurzel, Connelly. and Liefferink.2017a). We distinguish between the following four types of leadership: (1) structural leadership, related primarily to military and economic power; (2) entrepreneurial leadership, involving diplomatic, negotiating and bargaining skills; (3) cognitive leadership, relying on knowledge and expertise; and (4) exemplary leadership, i.e. intentionally or unintentionally acting as an example for others (cf. Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017).

8.3.1 Structural Leadership

In traditional international relations theory, structural leadership is foremost associated with military power which, however, is of little relevance to climate governance. Moreover, leadership and power are related but not identical. Actors in possession of (structural) power may not actually use it to exert (structural) leadership (Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017).

Economic power asymmetries are important in climate governance, including under polycentric conditions. For states, the size of the domestic market is an important source of structural power and can be used to exert structural leadership. Similarly, market share can facilitate leadership by firms. In Austria and Denmark, the conversion of the dominant supermarket chains to organic products was decisive for increasing the market share of organic food labels and their reputation in both countries (Hofer, Reference Hofer, Mol, Lauber and Liefferink2000). Consumers have economic power too. Their individual purchasing power may be very limited, although changing consumption patterns are often important drivers for change in products. Whereas one local windmill project may constitute an example of pioneering, thousands are likely to lead to fundamental shifts in the functioning of the energy grid (van Vliet, Chappells and Shove, Reference van Vliet, Chappells and Shove2005). Popular trends that can nowadays be rapidly shared via social media offer large potential for grassroots leadership. Some well-orchestrated consumer boycotts have mobilised considerable economic (consumer) power. For instance, a boycott against Shell was one of the decisive factors which made the company abandon its plan to dump the disused Brent Spar oil platform at the bottom of the North Sea in the 1990s (Löfstedt and Renn, Reference Löfstedt and Renn1997).

Another form of structural power derives from an actor’s contribution to the problem at stake or what may be called its systemic relevance. For instance, China has a pivotal role in global climate mitigation policies simply because it is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter. The bilateral agreement between Presidents Xi Jinping and Barack Obama in November 2014 constituted a milestone in the run-up to the 2015 Paris Agreement, not least because China and the United States together account for approximately 40 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions (Bang and Schreurs, Reference Bang, Schreurs, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017; Li, Reference Li, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017). With the more climate-sceptic Trump administration installed in the United States, a global leadership opportunity falls to China almost by default (cf. Li, Reference Li, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017; Mufson and Mooney, Reference Mufson and Mooney2017). Systemic relevance may also provide structural power to business. Good examples are investor groups such as the Ceres Investor Network on Climate Risk (which represents more than 130 investors, mainly in North America, and $17 trillion in assets) (Ceres, 2017) or the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (which includes more than 130 institutional investors in Europe and nearly $15 trillion in assets) (IIGCC, 2017). In November 2016, ten large oil and gas companies associated with the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative pledged to invest $1 billion to help develop low-emission technologies (OGCI, 2017). Apart from the large sum of money involved and the economic power exerted by the participating multinational companies, this initiative represents 20 per cent of global oil and gas production and accounts for about 12 per cent of historical greenhouse gas emissions (Bach, Reference Bach2016).

NGOs do not themselves wield much economic power. Instead, they derive structural power from their size and the support they receive from the general public. For NGOs representing hundreds of thousands or even millions of members, political legitimacy is a key factor for exerting leadership and/or pushing others (such as the EU, states and firms) to exert leadership. Forming alliances is a way for NGOs to increase further their legitimacy. A key example is Climate Action Network Europe, which claims to include more than 130 member organisations that represent approximately 44 million citizens in more than 30 countries (CAN Europe, 2017). Its structural power enables it to put substantial pressure on businesses or states by attracting considerable media attention (Wurzel, Connelly and Monaghan, Reference Wurzel, Connelly, Monaghan, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017b).

It makes sense to also include under the heading of structural leadership the use of formal institutional power (Wurzel, Liefferink and Connelly, Reference Wurzel, Liefferink, Connelly, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017c). This is relevant primarily for state actors (including agencies) with, for example, law-making and law-enforcing competences. Examples in an international context include voting rights in international institutions and the European Commission’s right to initiate and enforce EU law. These rights provide the Commission with a degree of structural power within a supranational governance context. Reflecting the complex MLG relations in the EU, Jänicke (Reference Jänicke, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017: 126) offers an interesting case of ‘enforced leadership’ when the Commission rejected Germany’s second National Allocation Plan, which aimed to distribute emissions allowances among emitting installations in the country, as insufficiently demanding under the EU emissions trading scheme (ETS). By forcing the German government to stick to its ‘self-proclaimed’ pioneer role, the Commission exhibited structural leadership (Jänicke, Reference Jänicke, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017: 119).

But formal institutional powers also offer opportunities for non-state actors to exert structural leadership. Structures for consultation and participation in liberal democracies warrant societal interests a seat at the table in most phases of the policy cycle, although the range of interests granted this right and the extent of their formal and informal influence may vary greatly. The right of standing in court also constitutes a potentially powerful weapon. A fairly spectacular example is the court case which the NGO Urgenda started against the Dutch state in 2012 (see also Chapter 3). It was aimed at increasing the government’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In 2015, the District Court of The Hague decided largely in favour of Urgenda (Liefferink, Boezeman and de Coninck, Reference Liefferink, Boezeman, de Coninck, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017). The possibility to lodge formal complaints with the Commission against the incorrect implementation of EU law has empowered citizens and particularly environmental NGOs to ‘fight’ their own national governments (Jordan and Liefferink, Reference Jordan, Liefferink, Jordan and Liefferink2004: 228). Interestingly, non-state actors may also themselves create formal institutions for exerting leadership. Examples include various international certification schemes (e.g. for sustainable forestry products or palm oil) set up by business partnerships and roundtables (Arts, Reference Arts, Koenig-Archibugi and Zürn2006; Schouten and Glasbergen, Reference Schouten and Glasbergen2011), as well as various national labelling schemes. By setting standards and procedures for participating in these schemes, businesses (in some cases in collaboration with the state) create their own framework for the inclusion of leaders and the exclusion of laggards.

8.3.2 Entrepreneurial Leadership

The main role of entrepreneurial leadership is to draw attention to the character and importance of the issues at stake, to propose innovative policy solutions and to broker compromises (Young Reference Young1991: 294). There is a certain degree of overlap between entrepreneurial and cognitive leadership (see later in this chapter). While the framing of issues and the development of innovative ideas is mainly a function of cognitive leadership, effectively setting or at least shaping the climate policy agenda and negotiating the adoption of particular solutions is a matter for entrepreneurial leadership. In practice, entrepreneurial and cognitive leadership are often utilised simultaneously as generating knowledge without efforts to disseminate it and to convince others of its relevance is not likely to be very effective (Young, Reference Young1991: 300–301; Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017). Nevertheless, there is a clear conceptual distinction between cognitive leadership, which is about the production of ‘intellectual capital or generative systems of thought’ (Young, Reference Young1991: 298), and entrepreneurial leadership, which is about diplomatic, negotiating and bargaining skills (Liefferink and Wurzel, Reference Liefferink and Wurzel2017; Wurzel et al., 2017; see also Chapter 7, where entrepreneurship is defined somewhat differently).1

Entrepreneurial leadership capacities are in principle available to both state and non-state actors, although the ability to mobilise and employ them may vary between different types of actors. Especially large states usually have fairly significant diplomatic resources at their disposal for networking, alliance-building and negotiating compromises. Massive diplomatic efforts by France were instrumental for the successful outcome of the 2015 Paris climate change conference (Bocquillon and Evrard, Reference Bocquillon, Evrard, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017). Large firms have considerable resources for various forms of consultation and lobbying activities with states and international organisations such as the United Nations and supranational actors such as the EU.

Small and medium-sized enterprises, NGOs and subnational governments have limited staff and financial capacities and therefore have to restrict themselves to clearly defined and well-targeted entrepreneurial efforts. A good example is the court case which was brought by Urgenda against the Dutch government. Urgenda is a network organisation with no more than 15 staff members (Urgenda, 2017). By making optimal use of the opportunity structures offered by the Dutch legal system, Urgenda managed to have a significant impact on the national climate debate. Cities sometimes conduct significant ‘paradiplomatic’ activities (Keating, Reference Keating1999), which consist primarily of entrepreneurial leadership efforts. They increasingly do so in the framework of vertical networks (e.g. networks of ‘green’ cities or climate cities) initiated and facilitated by national governments or the EU such as the Covenant of Mayors (Kern, Reference Kern2016; see also Chapter 5).

8.3.3 Cognitive Leadership

Cognitive – or in Young’s terminology ‘intellectual’ – leadership ‘relies on the power of ideas’ (Young, Reference Young1991: 300). It usually ‘operates on a different time scale than the other types of leadership … [because] the process of injecting new intellectual capital into policy streams is generally a time-consuming one’ (Young, Reference Young1991: 298).

That cognitive leadership is indeed a long-term process is aptly illustrated by the case of climate change. Almost one century passed between the discovery of the greenhouse effect by Svante Arrhenius in 1896 and its emergence as one of the key issues on the global political agenda. It required the activities of generations of scientists and activists, culminating in the shared 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and former US vice president Al Gore.

The capacity to frame and/or reframe problems, interests and future perspectives is arguably the most important feature of cognitive leadership by NGOs (e.g. Wurzel et al., Reference Wurzel, Connelly, Monaghan, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017b). Environmental NGOs have coined the term ‘hot air’ (Long and Lörinczi, Reference Long, Lörinczi, Coen and Richardson2009) and led the way in questioning the alleged sustainability of biofuels.

Scientists and experts are crucial for developing knowledge about the causes and effects of environmental problems as well as for possible solutions. Their knowledge can be used by NGOs, individuals (e.g. Al Gore) or policy-makers at various levels of climate governance. Scientists and experts can themselves also play an important role in the climate policy-making process. The IPCC, whose activities oscillate between science and politics, provides the key example (e.g. Hulme and Mahony, Reference Hulme and Mahony2010). Epistemic communities, which consist of scientists and experts (Haas, Reference Haas1990, Reference Haas1992), as well as knowledge brokers (Litfin, Reference Litfin1994), have played leading roles in the creation of various environmental regimes. However, climate scientists and experts have come under attack by populist movements and politicians, for example in the 2016 US elections and in the 2015 Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom.

Apart from scientific knowledge, the importance of ‘experiential’ knowledge about ‘how policies actually work at the street level or company level, and how implementation problems can be solved effectively’ (Haverland and Liefferink, Reference Haverland and Liefferink2012: 184) should not be underestimated. Experiential knowledge can be powerful ammunition for firms, branch organisations or other stakeholders to push for certain solutions (e.g. certain policy instruments) over others. Practical evidence that a given policy approach works and demonstrable support among policy addressees provide output legitimacy.

8.3.4 Exemplary Leadership

Exemplary leadership consists of providing good examples for other actors. States may act as exemplary leaders in climate governance both intentionally or unintentionally. Intentional exemplary leadership is provided by leaders which act as pushers while pioneers usually exhibit merely unintentional exemplary leadership (see Table 8.1). The United Kingdom’s early adoption of a national ETS with the intention of influencing the EU ETS (Rayner and Jordan, Reference Rayner, Jordan, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017) offers a good example of intentional leadership, while Germany and Denmark’s initial steps towards domestic energy transitions constitute examples of unintentional exemplary leadership (Andersen and Nielsen, Reference Andersen, Nielsen, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017; Jänicke, Reference Jänicke, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017; Wurzel et al., Reference Wurzel, Liefferink, Connelly, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2017c).

As discussed, intentional exemplary leadership may be problematic for firms as they may have sound commercial reasons for being the first (and possibly only) actor to introduce an innovative ‘green’ product in a particular market. As Dupuis and Schweizer (Reference Dupuis and Schweizer2016) have pointed out, only some corporate actors are ‘confident enough in the superiority of their abatement techniques or in their internal climate policy’ – and thus in their comparative advantage vis-à-vis competitors – to consider presenting themselves as examples for others. The activist company Fairphone explicitly adopted the ambition to demonstrate the feasibility of a more sustainable mobile phone. With its activist roots and the explicit goal to make its branch of industry more sustainable, Fairphone is arguably best described as a hybrid between a firm and an NGO, which shows that the once strict divide between business and environmental organisations has become permeable, at least to some degree (Biedenkopf, Bachus and Van Eynde, Reference Biedenkopf, Bachus and Van Eynde2016).

Exemplary leadership plays a particularly important role in the world of ‘green’ cities. A wide variety of city networks facilitate the exchange of good examples and local ‘best practices’ (Kern, Reference Kern2016). Cities which attempt to attract economic investment by branding themselves as ‘green’ (e.g. Andersson, Reference Andersson2016; Wurzel et al., Reference Wurzel, Jonas and Osthorst2016) may be confronted with the same dilemma as corporate actors. Increasingly, however, city networks are embedded in multilevel arrangements which are explicitly aimed at ‘spreading the word’. A key example is the Covenant of Mayors, which was set up by the European Commission in 2008. With its monitoring programmes, benchmarking exercises and collaborative initiatives, the Covenant of Mayors provides learning opportunities for more than 7,000 member cities (CoM, 2017). Competitions like the European Green Capital Award and the European Energy Award are geared towards showcasing exemplary leadership. With the possible exception of some very large or mega-cities, individual cities do not usually wield significant structural power and have little interest in actively pushing others with the help of cognitive or entrepreneurial efforts. By setting up the Covenant of Mayors and the European Green Capital Award, the EU provided entrepreneurial leadership in their place.

8.4 Conclusions

Leadership and pioneership can take many forms. This is the case in traditional top-down government systems, which are dominated by state actors, and even more so under conditions of polycentric governance, which encourage potentially any actor to become a leader or pioneer. This chapter has shown that a wide range of both state and non-state actors are capable of exerting leadership and pioneership. Importantly, the differentiation between different types of leadership and pioneership has allowed us to offer a more fine-grained analysis of the actions of leaders and pioneers in polycentric climate governance.

Large corporate actors usually have considerable economic power and experiential knowledge which can be mobilised to exert structural, cognitive and exemplary leadership. However, depending on their market position, corporate actors may be reluctant to use their leadership capabilities to push others to adopt and implement the same or similar policies and measures. Apart from the economic power of consumers, which is potentially very significant but difficult to organise due to collective action problems, the structural power of civil society actors is mostly limited to formal institutional power and, in the case of in particular large NGOs, legitimacy. Moreover, NGOs, scientists and experts are in a relatively strong position to exert cognitive leadership by framing and reframing problems and identifying cause–effect relationships and solutions. However, these actors can be challenged by, for example, populist movements and politicians, which reject their cognitive leadership. Cities (and by extension also other tiers of subnational government) finally have a large potential for exerting exemplary leadership.

All actors assessed in this chapter, moreover, are potentially capable of exerting entrepreneurial leadership. This may involve diplomatic and/or lobbying efforts, for which only some actors (e.g. especially large states, companies and business organisations) usually have sufficiently large capacities. Entrepreneurial leadership may, however, also entail relatively small-scale, well-targeted efforts, such as initiating a strategic lawsuit or sharing knowledge in a network of peers. Such entrepreneurial leadership opportunities allow actors of limited size and capacity to exert leadership far beyond the boundaries of their own polycentric unit.

Pioneers are especially able to exert exemplary and cognitive pioneership as well as structural and entrepreneurial pioneership. However, because pioneers do not intentionally seek to attract followers, they will exhibit these four different types of pioneership primarily internally (e.g. within their organisation) rather than externally (i.e. vis-à-vis other actors). However, powerful and/or highly innovative pioneers are likely to have a significant impact on other actors in polycentric climate governance, even if they do not intend to do so.

In this chapter, we assessed whether polycentricity might lead not only to a proliferation of leaders and pioneers, but also to narrowing down the range of their potential followers to only those actors which operate in the same relatively independent domain in which leadership or pioneership originates. We argued that in many cases, ‘systemic’ institutions are essential for widening the audience of polycentric leaders and pioneers to potential followers from outside their relatively small, functionally defined governance units. Relatively autonomous polycentric units maintain relations with other relatively autonomous polycentric governance units and are in turn embedded within larger international, supranational, national or subnational governance units. This makes it possible for both state and non-state actors – which function as leaders and pioneers – to attract followers from both within and outside relatively autonomous, functionally defined polycentric governance units. All types of leadership identified in this chapter are important in this regard. States and large firms can amplify the impact of structural leadership through international organisations and international markets. NGOs would be considerably less influential without overarching national and/or EU legal systems offering to them the opportunity to exert wide-ranging cognitive leadership. Without its formal role in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change machinery, the IPCC would never have been as influential as a cognitive leader as it is nowadays. And without the Covenant of Mayors, the European Green Capital Award and the European Energy Award, individual ‘green’ cities would be less well able to act as exemplary leaders and have an impact on other cities across Europe. Importantly, it was the EU which created these institutions in the first place.

In sum, leadership and pioneership originating in polycentric (or MLG Type II) units cannot be understood without taking into account their embeddedness in more hierarchical, top-down (or MLG Type I) arrangements. What seems to be important is to achieve the ‘right’ balance between more polycentric (or bottom-up) governance arrangements and hierarchical (or top-down) elements in climate governance. Finding this balance has become even more important since the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which encourages bottom-up or polycentric climate governance approaches.