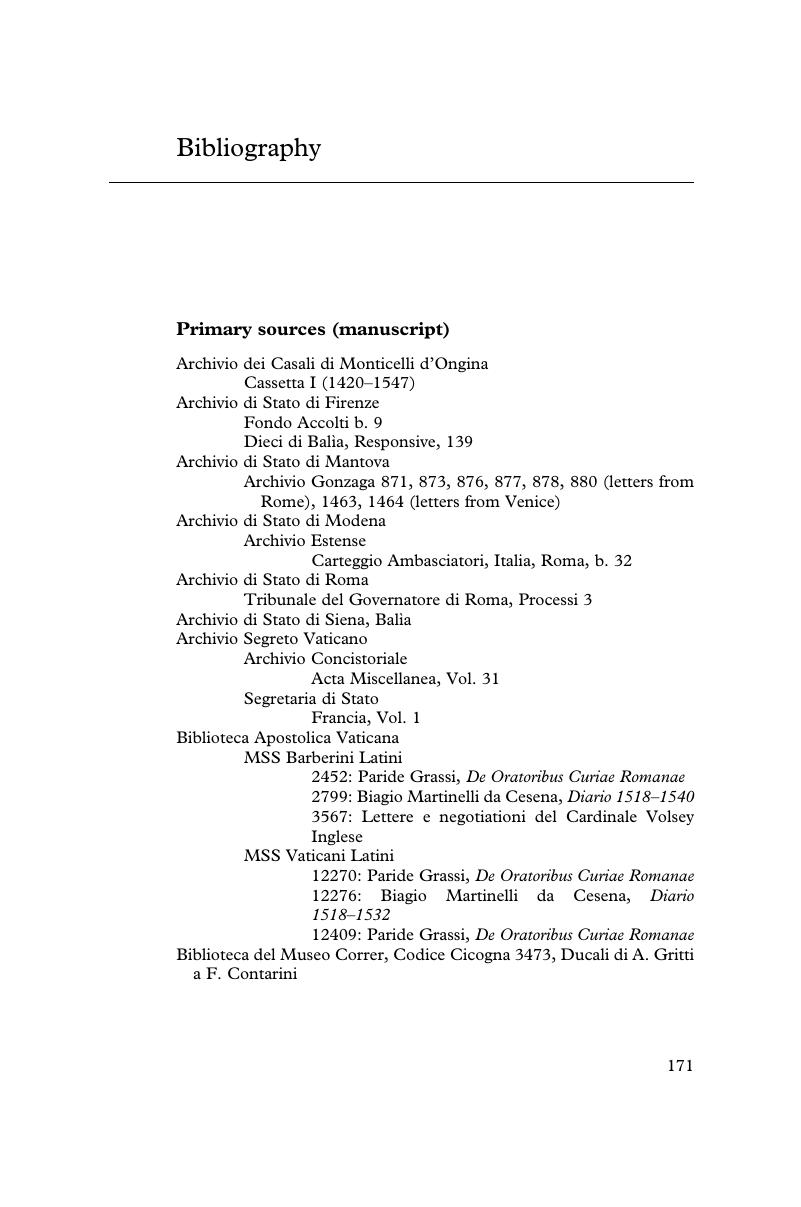

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2015

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Diplomacy in Renaissance RomeThe Rise of the Resident Ambassador, pp. 171 - 188Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015