I. Introduction

The fall of Suharto’s New Order in 1998 inspired hope that Indonesia’s fledgling legal system could be made fairer and more responsive to the interests of the poor. Decades of political meddling and institutional neglect had made the courts subservient to the privileged few, and the word hakim (“judge” in Indonesian) came to stand for hubungi aku kalau ingin menang: “contact me if you want to win.” As this “contact” was out of reach for most citizens, Indonesia’s legal system was seen as something to avoid rather than to invoke. In the period of reformasi (“reform”) after 1998, legal reform became a central focus of both the Indonesian government and various development agencies.Footnote 1

Paralegals have played a central role in these efforts. Since the foundation of Indonesia’s first legal aid organization, Lembaga Bantuan Hukum (LBH), in the 1970s, paralegals had been at the forefront of the opposition against the Suharto regime as they helped local communities during the recurring conflicts about (particularly) land and natural resources.Footnote 2 Inspired by LBH’s success, various groups – ranging from environmental organizations, trade unions, universities, and even political parties – started to adopt paralegal programs with the aim of helping citizens deal with a still remote and alien legal system. Foreign funding agencies have also provided support, seeing paralegals as a tool for “legal empowerment”:Footnote 3 as big donors like the World Bank, UNDP, and Open Society Institute increasingly felt that a focus on a “top-down” reform of legal institutions – like making the courts or the police work better – was not enough to enable common Indonesians to make use of these institutions, they have started to fund projects that train and supported paralegals.Footnote 4 In a recent count, Indonesia now has at least 622 legal aid organizations in all provinces, although two-thirds of these are based in provincial capitals.Footnote 5 A recent survey among 229 of these organizations revealed that 56 percent make use of paralegals. These legal aid organizations claim to have trained a total of 16,240 paralegals over the past decade. Yet they also report that a much smaller number of individuals remain active after such training.Footnote 6 Based on the numbers provided by the surveyed legal aid organizations, it can be estimated that there are currently between 4,000 and 6,000 active paralegals working for legal aid offices in Indonesia.Footnote 7

Recently the Indonesian government has also stepped up its involvement. In an ambitious reform strategy called “National Strategy Access to Justice” the Indonesian government stated in 2008 its aim of enlarging the number of paralegals.Footnote 8 In 2011 the Legal Aid Bill was adopted, which provides funding to expand the scope of legal aid efforts.Footnote 9 After this law became effective in 2013, 593 legal aid organizations applied in 2013 for accreditation to the Ministry of Law and Human Rights in order to be eligible for this financial support. Of these, 310 organizations have been accredited.Footnote 10 The accredited organizations can receive a maximum of US$500 as support for handling a case. In 2013, the only year for which reports are available, the Indonesian government provided funding for 194 organizations for the handling of 2,315 cases with in total Rp 5.6 billion (about US$450,000 at that time, or US$195 per case). Of this total budget, 70 percent was spent on cases involving litigation in court and only 8 percent went to training activities.Footnote 11 This suggests that paralegals have actually derived relatively little support out of the Legal Aid Bill. Yet the very mention of paralegals in this law illustrates that, after decades of being a marginal instrument of the opposition against Suharto, paralegals have now gone mainstream as an important channel to make Indonesia’s legal system more accessible.Footnote 12

This chapter discusses the impact of the presence of paralegals on processes of grievance and dispute handling in rural Indonesia, focusing on the community-based paralegals trained under programs set up by the World Bank and UNDP. Through both quantitative and qualitative material this chapter focuses on three main activities of paralegals – mediation, legal accompaniment, and community organizingFootnote 13 – to discuss how and under what circumstances these activities impact the way local disputes and grievances are addressed in villages in three Indonesian provinces: West Java, Lampung, and north Maluku. The main argument of this chapter is that in the context of a distrusted legal system, a New Order tradition of emphasizing harmony, and a rich tradition in alternative dispute resolution, the contribution of Indonesia’s paralegals lies – at least in the short run – not so much in facilitating access to the formal legal system but rather in countering the impact of power imbalances on processes of grievance and dispute handling. In other words, the contribution of Indonesia’s paralegals does not lie so much in facilitating the implementation of the law, but rather in extending the shadow of the law:Footnote 14 by inserting legal considerations more forcefully into the (often informal) process of grievance and dispute handling, paralegals can offset and sometimes neutralize the impact of power imbalances between disputants.Footnote 15

II. Approaches to Studying Access to Justice

With these arguments we adopt a relational approach to interpreting the unequal capacity of citizens to use available legal systems to defend their interests. Surprisingly, paralegal projects rarely come with an explicit analysis of the causes of this unequal capacity. In Indonesian paralegal programs two main, contrasting approaches could be identified. Following Heller and Evans these approaches could be termed residualist and structuralist.Footnote 16 A residualist approach attributes the unequal capacity to access legal systems to the weaknesses of available legal institutions and the limited familiarity of citizens with these institutions. The inequality, in other words, is a residue of the way the state developed (or failed to develop) and the way citizens avoided interaction with this state. Such an analysis suggests that a combination of bottom-up and top-down measures could make legal institutions more accessible to poorer citizens: on the one hand policies aiming at legal reform could strengthen legal institutions, while on the other hand legal education and legal aid could boost the capacity of ordinary citizens to deal with these institutions. It could be argued that most paralegal programs, including those of the World Bank and UNDP, adopt such an analysis.Footnote 17 With their emphasis on “legal empowerment” these programs prioritize strengthening individual (legal) capacities over changing social structures.

This is why, according to the structuralist approach, “residualists” fail to address the root causes of the unequal capacity to benefit from the formal legal system. The structuralist approach sees this unequal capacity as a by-product of the nature of global production and the impact of market forces on the functioning of the state. In this view, the difficulties that poorer citizens face when dealing with the formal legal system are a symptom of the way market forces are systematically disempowering poorer citizens. In this view the legal system is to be distrusted, as it often operates as a tool in the hands of (economic) elites who use the law to reduce labor costs and acquire control over natural resources.Footnote 18 The solution to unequal legal capacities does, therefore, not only lie in merely helping individuals bring their cases to court, but rather in using such cases to build up awareness and create demand for the overhaul of the legal system. These considerations led to the development in the 1980s of the concept of “Structural Legal Aid” (bantuan hukum structural, BHS) at LBH, which aimed to use legal cases to change the unequal distribution of power within Indonesian society.Footnote 19 In the 1990s legal aid organizations like YLBHI and HUMA further developed these ideas into a new legal aid strategy called Critical Legal Education (Pendidikan Hukum Kritis, PHK). PHK emphasized local customary law as an antidote to the oppressive legal system. A new type of paralegal called pendamping hukum rakyat (PHR, “the legal assistant of the people”) was trained, whose role went beyond providing legal aid and community organizing, as PHK-paralegals are also expected to engage in critical legal analysis to challenge the domination and oppression inherent in Indonesia’s laws and policies – in particular in Indonesia’s laws pertaining to land and natural resources.Footnote 20

While both types of arguments are relevant, they are of limited value to analyze the actual contribution of paralegals to addressing these inequalities. While the residualist approach overestimates the agency of justice seekers, the structuralist approach underestimates their agency. By focusing on relatively technical solutions such as (legal) training and policymaking, the residualist approach risks bracketing broader societal and economic inequalities that underlie legal inequalities. Yet the structuralist approach paints an overly deterministic picture, as it creates the impression that individual struggles cannot make a difference without a structural overhaul of the economic and legal system. Furthermore, such a broad approach is not precise enough to analyze the practical and creative ways in which justice seekers use their (limited) resources to successfully overcome injustices.

For these reasons we turned to relational sociology to discuss the impact of paralegals on processes of grievance and dispute handling. This current in modern sociology, associated with eminent social scientists like Pierre Bourdieu, Norbert Elias, and Charles Tilly, departs from the proposition that the attitudes and interests of individuals are not given units of analysis, but rather a product of the nature of the relationships in which human lives are embedded. Relational sociology thus studies social inequality not merely in terms of an uneven distribution of talents or resources between individuals, but rather in terms of the nature of interpersonal relations that enable some individuals to accumulate resources and to make this accumulation appear legitimate.Footnote 21 An unequal capacity to, say, win a dispute over landownership, is in this approach not merely the result of a lack of individual capacities to make an argument or to invoke the law, but also a product of the position of disputants within society – since it is by virtue of these positions that some disputants possess the status, knowledge, and influential connections that put them at an advantage. In other words, the strategies that people adopt to settle a dispute or address a grievance are a product not just of the normative or legal merits of their claim but also of the personal resources that come with their position within society. We will make use of the concept of “capital” to describe the content and impact of various forms of such advantages: following Bourdieu, power differentials between individuals can be described in terms of an uneven control over various forms of capital. Bourdieu distinguished four main “species of capital” to highlight existing power differentials between people: economic capital (monetary or material possessions), social capital (contacts with useful individuals), cultural capital (primarily, the possession of various forms of knowledge, including legal knowledge), and symbolic capital (prestige and social status).Footnote 22 The distribution of these forms of capital, and their perceived value, are a product of the interdependencies between people. In the words of a common analogy in relational sociology, these forms of capital are related to the social “game” in which people are involved: while a farmer in West Java might not see the importance of publishing in an obscure academic journal, a Dutch academic would not see the need for the varied levels of politeness that can be conveyed through the Javanese language.

Such a relational approach is not just useful to understand how paralegals operate at the crossroads between law, social norms, and relations of power. This approach is also helpful to understand how the paralegals’ own position within the community affects their effectiveness. As community-based paralegals have long-standing relationships with the people they are supposed to serve, their social background and their embeddedness in the local community have a large impact on the way they operate. Paralegals operate in villages alongside other individuals who derive status and money from solving local disputes. Various local institutions (adat councils, religious courts, village councils, etc.) and actors (village heads, local politicians, preman, etc.) are involved in dispute resolution, sometimes apply their own laws and regulations (though not always written down) that can differ from state law.Footnote 23 For this reason we have focused not only on the case handling by paralegals, but also on their role within larger struggles for status and power that mark village politics.

This chapter focuses on the paralegals trained under the World Bank’s Justice for the Poor project and UNDP’s Legal Empowerment and Assistance for the Disadvantaged (LEAD) project. Both programs worked with “community-based paralegals,” which meant that inhabitants of designated project villages were selected as paralegals, serving only people from (or around) their village. The selected villagers received basic training on Indonesia’s legal system, as well as on case handling and mediation: while “providing legal services” was the main aim, paralegals were instructed to work alongside existing (traditional) dispute resolution mechanisms.Footnote 24 The paralegal program of the World Bank – called “Revitalisation of Legal Aid” (RLA) – worked generally with village-level teams of two men and two women who worked out of a legal aid posko (“post”), usually the house of one of them. For the duration of the project they were supported by “posko facilitators” and “gender specialists” who provided assistance and who functioned as a liaison with the “community lawyers” who were involved in the project to provide paralegals with legal advice for the more complex cases. The RLA program operated in three provinces (Lampung, Nusa Tenggara Barat, and West Java) where for each province an (legal aid) NGO was involved as “implementing agency.” In these three provinces the project worked with in total 120 paralegals, ninety-five village mediators, twelve posko facilitators, six community lawyers, and six gender specialists.Footnote 25 LEAD also worked with community-based paralegals,Footnote 26 of which some were trained on specific issues (such as gender, land, and natural resources), while other paralegals were also trained as general community-based paralegals. They were selected from project villages in north Maluku, central Sulawesi, and southeast Sulawesi. UNDP also worked with local NGOs who were made responsible for the training and support of paralegals. This support was organized through “field officers” who traveled to the project villages. In total, the LEAD project claims to have trained 400 paralegals.Footnote 27

This chapter is based on two sources of material: (a) a qualitative study on local dispute resolution in both paralegal and non-paralegal villages; (b) a quantitative analysis of a database of 338 cases that were handled and reported by the 120 paralegals supported under the World Bank’s Justice for the Poor program. Our research has focused on the functioning of paralegals that were part of UNDP and World Bank paralegal programs, and in a later stage, on paralegals supported under the aegis of legal aid projects supported by Open Society Institute.Footnote 28 We documented twenty-one cases that were reported to and handled by paralegals, while also documenting ten similar cases in the same districts (but different villages) where paralegals were not involved. We focused on the functioning of paralegals in three provinces: Lampung, West Java (locations of the Justice for the Poor program), and Halmahera Timur (where UNDP financed a paralegal program).Footnote 29 The quantitative study focused on 338 cases handled by paralegals in West Java, Lampung, and West Nusa Tenggara between October 2007 and April 2009. All these paralegals were trained under the World Bank’s Justice for the Poor program. As part of this project paralegals were asked to fill out basic forms about the way they handled each case reported to them. While this material needs to be treated with some caution,Footnote 30 we have used it to link our in-depth case documentation with a more general overview of the types of cases received by paralegals and the manner they were dealt with.

III. Mediation: An Accident in a Kroepoek Factory

Siswanto had been working for twenty years in the kroepoek factory owned by Sugiono when, on October 12, 2009, he lost two fingers in an accident with the factory’s machine. After the incident Siswanto could not work for four months, and he had to spend Rp 7 million for the treatment of his hand. During this time, Siswanto tried to use the health insurance (Jamsostek) that Sugiono had arranged for him in 2005. This health insurance scheme requires the employer of more than ten employees to arrange health insurance, for which some amount can be deducted from the salary. When Siswanto contacted Jamsostek, he learned that Sugiono had paid the fee only once, in May 2005, while he had cut Siswanto’s daily salary by Rp 3,000: since 2005 Siswanto had received Rp 25,000 per day (US$3) instead of Rp 28,000. Consequently Siswanto could not reclaim the costs of the treatment from Jamsostek.

Siswanto as well as his brother then approached Sugiono to ask him to pay for the incurred costs. Sugiono agreed to pay only a small amount; he said that the accident was due to negligence on Siswanto’s part, so the costs would fall to him. No agreement was reached at this point and Siswanto’s brother was shooed out of Sugiono’s house.

This labor dispute is an example of a conflict with a marked power differential between disputing parties. Sugiono’s father is a prominent member of the PDI-P, which assures him of support among the police and the village leader. He is the owner of the factory where Siswanto is employed, and is thus important for Siswanto’s livelihood. Furthermore, thanks to his fancy clothes and worldly manner, he can come across as reliable and convincing when he says that Siswanto was to blame for the incident, while the uneducated Siswanto lacks any knowledge of the legal system that might enable him to invoke the law to strengthen his claim while his shyness and soft-spokenness also undermine his credibility. As a result of these disparities in terms of social, economic, cultural, and even symbolic capital, Siswanto could safely calculate that, whatever laws might exist, Sugiono would not be able to invoke them – and if he would, Sugiono’s contacts and symbolic capital would ensure that his interpretation would prevail. It is thus not surprising that Sugiono at first ignored Siswanto’s request for compensation. There had been two other accidents in his factory; in these cases, the workers decided to meekly accept the small compensation that Sugiono offered.

In this case, the involvement of a paralegal, Agus, had a demonstrable effect in addressing the power differentials. After Sugiono’s unwillingness to pay compensation, Siswanto approached the paralegals of the BHK posko in Margodadi. They went over the case; Agus analyzed that available labor laws do stipulate that employers have to pay the salary of a worker when he cannot come to work due to sickness, but that as Siswanto did not have a salary slip or contract, it would be difficult to claim this money. Agus decided that it would not be helpful to bring the case to Disnaker (Dinas Tenaga Kerja, the governmental institution set up to deal with labor disputes).

Agus then went with Siswanto to negotiate with Sugiono. Now the factory owner did show some willingness to meet and discuss the claims. Agus claimed Rp 13.5 million compensation, an amount that did not include the money deducted from Siswanto’s salary on the pretext of providing health insurance. During the first meeting, Sugiono refused to pay any money, stating that he had already paid Rp 1.3 million for the medical costs. A second meeting in the house of the kepala desa was also inconclusive, but during the third meeting, again in the house of the kepala desa, with the family members of both parties also present, it was agreed that Siswanto would pay Rp 4 million as compensation to Sugiono. Afterward, when Sugiono was asked why he paid this amount to Siswanto while he had refused to pay the workers who previously got injured, he said:

Before they [the workers] understand us and we understand them, so there is not too much complaining. Now there is too much complaining and involvement of outsiders. If we bring in the law it eats time and costs. They know about the law, I don’t. So I prefer to use our own way. They kept reminding me of the law and the labor rights when they proposed 13 million. I felt we should solve it secara kekeluargaan (i.e., informal mediation), instead of using the law. If we use the law it will increase all the cases, and all the money I have to pay to employees will increase. You cannot negotiate with the law. So we decided to accept a solution that was made through negotiation.

Similarly we asked the paralegal, Agus, why Sugiono listened to him and not to Siswanto’s brother:

If his brother came, he is just a villager and he has no power. When I came as a paralegal, the boss thought, “ok, now it’s serious, now there is a legal aspect to the case.” We were not a threat, but we referred to our legal analysis of the case. We said to them, we can bring this case to Disnaker. Then the company agreed to mediate; they were afraid of that.

Both Agus’ and Sugiono’s remarks illustrate how the impact of paralegals on local dispute resolution lies in the enlargement of the shadow of the law. It is not the facilitation of the access to the formal justice itself that makes a difference, it is the threat of starting legal proceedings that improved Siswanto’s bargaining position vis-à-vis his employer. By bringing legal considerations to the table, and by conveying a credible threat that these laws might actually be invoked by going to Disnaker – the labor relations department – paralegal Agus could address the unequal bargaining position between Siswanto and Sugiono. In a well-functioning justice system, Siswanto’s interests might be better served by seeking full compensation at the labor relations court. But because of the informality of Siswanto’s livelihood (as he lacks official papers), as well as an experience with a lackadaisical implementation of labor laws by Disnaker, Sugiono and Agus preferred to settle the case through negotiations:

Our experience is that Disnaker is not neutral, that [it] will not mediate well. And then, if [it] do[es] not we woud have to go all the way to the Industrial Relations Court. That is too expensive and takes too long.

In short, in the context of an imperfect legal system, the contribution of paralegals in such conflicts often does not lie in facilitating the actual application of the law; it is by representing the threat that the case might indeed reach the police or the courts. The stronger party in a conflict often avails itself of various extralegal means to manipulate the outcome of a conflict; the involvement of a paralegal raises the costs of doing so – and thus improves the bargaining position of the weaker party.

This role of paralegals in extending the shadow of the law rather than facilitating the application of the law should be interpreted in the light of the necessity for most disputants to maintain good relationships within their community. As the next case study illustrates, if clients attach great importance to maintaining good relations and adhering to social norms, the legal considerations that paralegals insert into local dispute resolution can have limited impact.

IV. Taking Responsibility for Car Theft

Harjo, a tailor, had recently met Joni, and he had invited Joni to stay at his place. For a short vacation, Joni proposed to hire a car and go to the beach. Harjo agreed and he hired a car and a driver from the local car rental run by Pak Karyo. After driving together to the beach, Joni stole the car: under the pretext of buying a durian, he managed to get the keys to the car from the driver, and he drove off, leaving Harjo, his family, and the driver stranded at the beach. Neither Joni nor the car ever resurfaced. When they got back, Karyo, the owner of the rental company, demanded compensation for the loss of the car. During the first discussion he demanded Rp 65 million from both the driver and Harjo.

Harjo’s income as a tailor was not sufficient to pay such an amount, and Harjo started to fear that he would have to leave his house. This was the moment he approached Subur, the local paralegal. Subur’s legal analysis of the case was that Harjo was not liable for the theft; he argued that, if the police would not find Joni, only the driver and Pak Karyo should foot the bill. Harjo listened to this advice, but he did not heed it: he did not invite Subur for the next mediation session (which was led by the village head), and during this session he ignored Subur’s advice – he agreed to pay Karyo the requested Rp 65 million, and a letter was written to this effect. Afterward Karyo was distraught, and started thinking about selling his house. As he later said of this mediation session: “I saw Karyo showing good will so I put aside the legal logic; it was more like we had family relations, with another sort of logic. So I did not want to insist on the legal position.” A week later he approached Karyo again. During this last session, again conducted in the presence of the village head, Karyo changed his mind, and agreed to settle the issue for just Rp 10 million. Afterward he said that he changed his mind because he felt that Harjo had been reasonable, and that in any case it would be unlikely that Harjo would be able to pay more. It seemed that Karyo had pinned most of his hopes on his insurance.

Not only had Harjo ignored the advice from paralegal Subur, he also did not want him to be present. It is worth quoting his reasons to do so:

The paralegals told me about the rule of law. We had a meeting at the posko. It was to prepare. Like if people go to war, you prepare your weapons. But I know that Karyo has power; I know that if I bring a paralegal, it will indicate that I prepare for conflict. I wanted to prevent him from using that power against me; I did not want him to become angry.

Harjo took into account the need to maintain a good relationship with Karyo: Karyo was from a relatively wealthy and well-respected family, and Harjo was apprehensive about starting a conflict with such a family. This family had the financial means to hire a good lawyer and win any court case, and the family had such a standing that Harjo felt many of his clients had actually stopped bringing work to him after the incident. In this case, Harjo’s best option was to hope for an amicable solution, which in this situation worked out.

This case of the stolen car illustrates how paralegals operate at the crossroads between normative systems. Disputes between actors living in close proximity are shaped not only by legal provisions but also by the need to maintain good relationships within the community. That means that social norms and local (power) relations can sometimes make it impractical to take recourse to the law, as this is seen as unacceptable, unpractical, or an impolite form of addressing conflict. Some of this attitude could be traced back to the New Order period, when state propaganda regularly emphasized the need to solve conflicts in harmonious ways.Footnote 31 This stress on social harmony often favors the wealthy and the powerful, since it undermines the attempts of the less privileged to address these inequalities: when a more powerful party would be unwilling to settle an conflict secara kekeluargaan (i.e., through mediation), the importance attached to social harmony discourages a weaker party from open conflict behavior, like using the law to defend one’s interests. Paralegals, through their socialization of the law, can serve to address this cultural heritage and to make legal action a more acceptable form of addressing injustices. Particularly in cases when local mediation favors the more powerful party, generating acceptance of the relevance of legal provisions can serve to support weaker parties. At the same time, Harjo’s case illustrates how the strategies that disputants employ involve the weighing of legal considerations and local norms of “proper behavior,” as well as assessments of the nature of social relations.

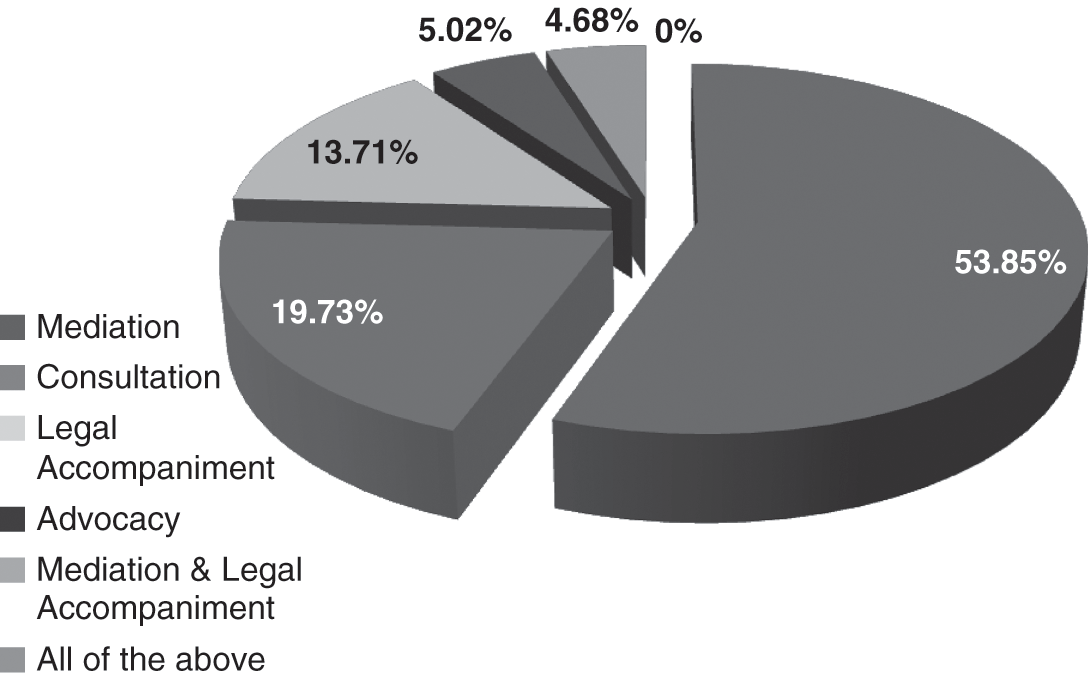

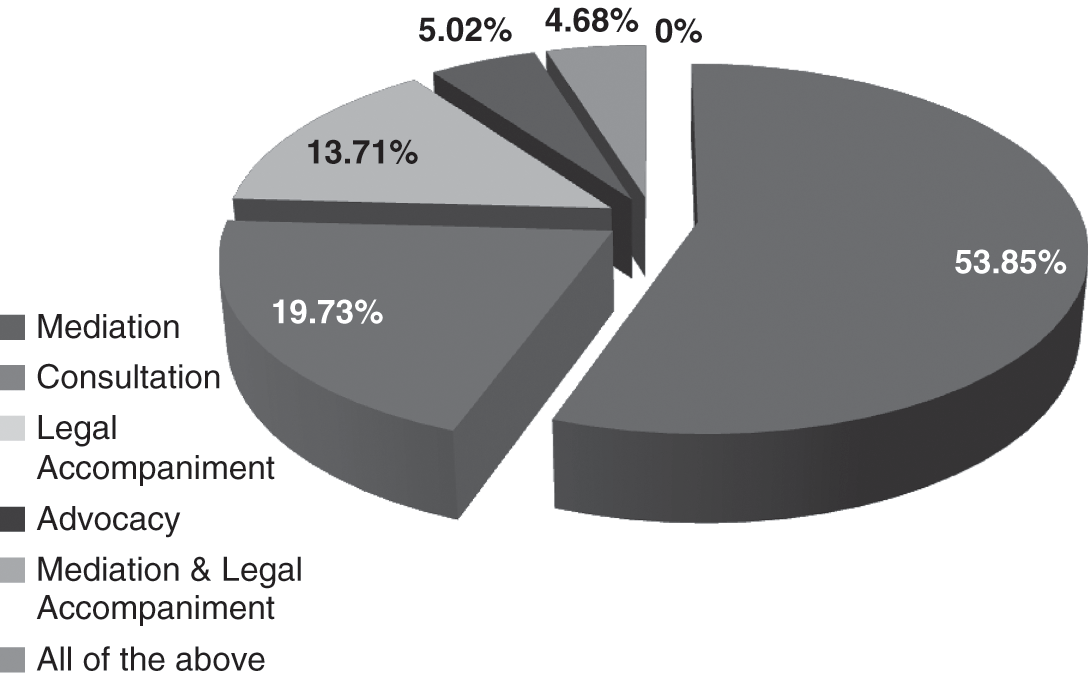

This avoidance of open conflict – whether or not a product of New Order propaganda – is one of the reasons why the studied paralegals took few cases to the police or the courts. While the facilitation of the interaction with formal legal institutions (i.e., legal accompaniment) is the activity most commonly associated with paralegals, the graph that follows shows that this activity forms a small aspect of the functioning of the studied paralegals in Indonesia.

Only in 14 percent of the 338 reported cases did paralegals help their clients report the problem to the police or a local court, with a further 5 percent of cases involving both mediation and legal accompaniment. In 20 percent of the cases clients approached the paralegal for advice, which led to no further action on the part of the paralegal. Advocacy is a rare activity for paralegals, employed in only fifteen cases (5 percent) out of the reported 338. In most cases (54 percent) paralegals deal with the issues brought to them by conducting or facilitating a mediation process between conflicting parties.

Figure 4.1 Case handling by paralegals

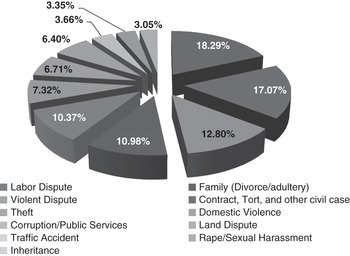

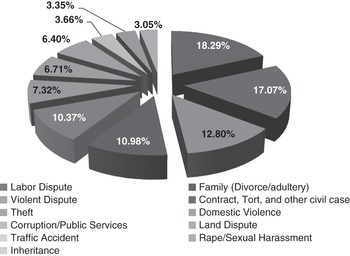

The table that follows shows a breakdown of the types of cases paralegals are commonly involved in. The highest number of cases reported to paralegals involved family and labor disputes (17 percent and 18 percent, respectively) – types of disputes that lend themselves well to more informal dispute resolution. But also in criminal cases like theft or violent disputes paralegals rarely advise to take a case to the police or the court, only in 10 percent and 13 percent of cases, respectively – as these types of cases were also mostly dealt with through informal mediation.Footnote 32 It turns out that in cases concerning rape and labor disputes paralegals feel most confident in taking recourse to the formal justice system (30 percent and 21 percent of reported cases, respectively).

Figure 4.2 Type of case

These statistics illustrate our earlier observation that the work of Indonesian paralegals only infrequently involves facilitating access to the formal justice system. While paralegals are not observed to have much impact on the actual use that people make of the formal legal system, their impact lies more in conveying a threat that legal procedures might be invoked. This threat not only affects the outcome of village-level mediation (as in the cases discussed earlier), but also smooths (to a certain extent) the interaction with particularly the local police. In the context of a police force that is often perceived as threatening and corrupt, paralegals can sometimes strengthen the bargaining position of villagers vis-à-vis the police. As the next case study illustrates, this often serves to keep the police out – in convincing the police to have a case settled through informal mediation.

V. Legal Accompaniment: a Dukun Finds a Thief

Sulis had been working for two months at a small stationary shop, when the owner of the shop, Ruhaini, accused her of stealing Rp 2.3 million from the shop’s register. There were no eyewitnesses and Sulis denied having stolen money. But as Sulis had been alone in the shop, Ruhaini felt certain that Sulis had taken the money. She consulted a local dukun (a healer who masters magic), whose divination also pointed to Sulis. At that point she went to the police. Ruhaini comes from a prominent family in the region and her father is the ex-head of the district police. So both the village head and the local police officers decided to take Ruhaini’s word for it, and the police duly arrested Sulis. With Sulis in jail, Ruhaini went to Sulis’ family together with the village head, a close friend of her father’s. They told the stricken family that Sulis would be transferred to another jail if they would not sign a letter (a surat perdamaian), promising to repay the Rp 2.3 million. Sulis’ family saw no other option but to sign the letter that the village head drafted, which admitted Sulis’ guilt. With that letter, Sulis’ brother went to the police – with the hope that this agreement would convince the police to release Sulis. But the letter was not enough. The police officials asked Sulis’ brother for Rp 5 million. He went around his village to collect as much money as he could: in the end he paid the police Rp 2 million before they agreed to stop the case and release Sulis. A few days after Sulis was released from jail, Ruhaini sent two men to her house, who threatened to “play judge” if her family would not pay the promised Rp 2.3 million.

Sulis’ parents grew sick with worry about having to pay this insurmountable amount of money. Sulis and her father decided then to visit Pak Agus. Agus is a local paralegal who has received basic legal training from KBH Lampung. The signboard in front of his house – identifying his place as a “legal aid post” – and his record as a local problem solver generate a steady stream of visitors like Sulis. He advised them not to pay the Rp 2.3 million. With a surat kuasa – a “letter of attorney” signifying that he was her legal representative, Pak Agus went to the village head to organize a mediation session. The meeting at the balai desa was tense, as Ruhaini kept insisting on the Rp 2.3 million. Sulis’ family and Pak Agus told them that the letter was not valid; they argued with the village head and they stood their ground. Ruhaini threatened to get Sulis arrested again, but three months after the incident nothing more had happened. When asked about what he had learned from these experiences, Sulis’ brother replied, “our neighbors were surprised that we could win against powerful people. We are an example for poor people. If we are enlightened, we do not always have to be the victim; we can fight.”

Sulis’ experiences illustrate two key and interrelated weaknesses associated with Indonesia’s formal legal system: both the courts and the police are considered to more responsive to the wishes of more powerful sections of society, and they are prone to rent-seeking. The police officials did not really investigate whether Sulis was guilty; their standard operational procedures for such a case seemed to matter less than Ruhaini’s superior status and contacts, and they demanded a very high fee for Sulis’ release. The inequality between Ruhaini and Sulis in terms of their social and symbolic capital made the police more well disposed toward Ruhaini. Given such experiences, it is no surprise that surveys regularly indicate high levels of distrust toward the formal legal system. Because of the costs and the perceived corruptibility of the police, an informal settlement of a dispute or a violation is often preferred, even when it concerns criminal acts.Footnote 33 Furthermore, as one survey indicated, 50 percent of respondents felt that the formal justice system was biased toward the rich and the powerful, against only 15 percent for the informal justice systemFootnote 34 – i.e., the mediation done by village heads, customary (adat) leaders, and other local notables. Even if no bribe is paid, taking a case to court can be expensive and time-consuming, while there is a general perception that, due to corruption, there can be no certainty about the way a law is applied in court. Police officials generally have paid a considerable amount of money to their superiors to get their jobs, which means that often they cannot avoid demanding a bribe from people like Sulis – to make good on their earlier “investment.”

The capacity of paralegals to help their clients deal with the police – whether to stop a case, to report a case, or to accompany an accused – is again largely due to the threat that they represent: their presence, and their links to lawyers of legal aid associations, suggests to police officials that any misbehavior on their part might actually lead to an official complaint. While police officials can often assume that uneducated villagers will not have the skills or stamina to protest against bribe-taking or foot-dragging – the police officials in this case seemed to have few qualms about asking Sulis for Rp 2 million – the involvement of paralegals can serve to discipline individual police officials. Furthermore, this involvement seems to impart some confidence to their clients; Sulis and her family, for example, said repeatedly that they felt “less panic” and “more secure” when Pak Agus got involved. The connections that a paralegal has with outside organizations – like a legal aid association – are crucial for this interaction with the police, because these links contribute considerably to the impression that a paralegal might create problems for a misbehaving police officer.

In this context, it is not surprising that paralegals are reluctant to advise a client to bring a case to court. In the context of a corruptible and inaccessible formal legal system, the work of paralegals more often consists of finding alternative solutions in order to avoid or minimize and scrutinize the involvement of the police – even to victims of criminal offences.

VI. What Makes a Paralegal Successful?

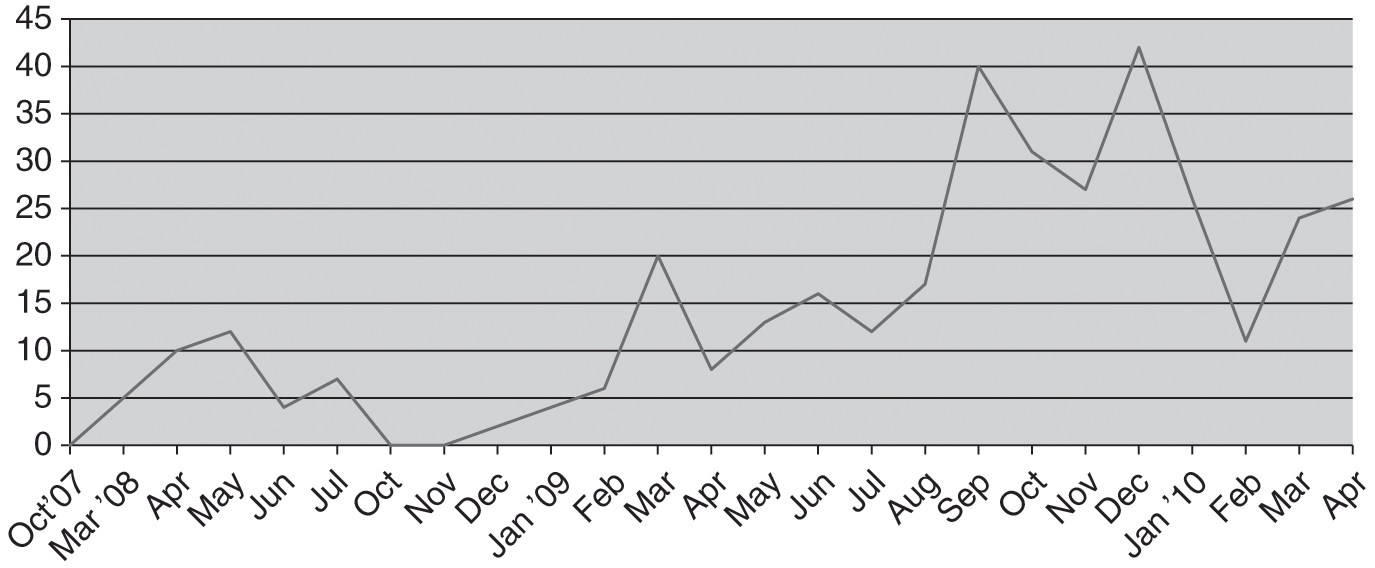

Yet not every studied paralegal operated as successfully as Agus. While some of the paralegal poskos set up by the World Bank program reported almost no cases in more than two years, other poskos received more than twenty. While it has to be taken into account that many paralegals failed to report particularly the smaller cases, 338 cases is not a high number for 120 paralegals and ninety-five mediators working for two years. Furthermore, as the next graph shows, their activity was also not evenly spread in time: most of the case handling of the paralegals was concentrated in the last nine months of the project. In short, it took time before villagers trusted paralegals sufficiently to report their problems to them, and some paralegals never really managed to establish this trust.

These observations suggest that the mere fact of being a trained as a paralegal is not enough to convince villagers that he or she will indeed be of any use. In all the project areas it took considerable time before people started to trust their paralegals enough to bring their problems to them. In some areas the local community never really developed this trust. Through our fieldwork we identified a number of additional factors that influenced whether a paralegal was capable of gaining the trust of his or her community.

The World Bank’s RLA project used the following criteria to select paralegals: (a) trusted by the community; (b) actively involved in community organization or activities; (c) having organizational, advocacy, or legal aid experience. UNDP’s LEAD program used similar criteria. As both programs mostly operated in rural areas, most of the paralegals we encountered were farmers with limited education, aged between thirty and fifty.Footnote 35 Both UNDP and the World Bank programs worked with (relatively young) “facilitators” who were supposed to provide support to paralegals when dealing with complex cases. Yet apart from these general similarities in social background of the paralegals, there were three important differences that, in our view, accounted for the different levels of activity between paralegals.

Figure 4.3 Cases reported by paralegals by date

Paralegals are not the only ones offering help to local disputants or victims of a crime. In fact, the inaccessibility of the formal legal system has engendered a whole range of “legal intermediaries” – i.e., actors involved in dispute resolution and the facilitation of interaction with the police and the courts. There are village heads, customary authorities, religious, and other local leaders offering informal justice mechanisms for dispute resolution. Since disputing parties are looking for reassurances that any agreement will be adhered to, it makes sense to involve the village head: because of his official status and his links with police and other government officials his signature on an agreement letter (surat perjanjian) can convince the police officers to take action. That means that often paralegals play a small role as advisors next to existing local disputing mechanisms. Furthermore, one can find various kinds of “fixers” – journalists, NGO staff members, case brokers (makelar kasus) and even local criminals (preman) – who offer to use their contacts and knowledge of procedures to report a case to the police or to bring a case to court (for a fee). Both village heads and paralegals called these fixers and their organizations “bodrex NGOs” or “bodrex journalists,” referring to a medicine called Bodrex, used in Indonesia for all sorts of illnesses: these fixers jump on any kind of issue, hoping to make some money by offering their services. The presence of paralegals can be perceived as a threat for those whose local status and income depend on their facilitation of contact with the police. In this competition, skilled makelar kasus or bodrex NGOs can receive more cases than paralegals as they actively go around looking for them. The special qualities of paralegals – their legal training and their connections to supra-local (legal aid) associations and the fact that they do not ask for a fee – do not necessarily make their services superior to these various alternatives, particularly if there are locally influential leaders with the skill of brokering and enforcing a compromise between disputants.

That means that, in order to attract clients, the services of paralegals need to be perceived as superior. The following three factors seem to influence this evaluation. First, the most active and successful paralegals often already have had some success in taking up community problems before becoming paralegals, often through involvement in organizing events or protests. Agus easily acquired clients because his previous activities as a local activist had given him an image of a trustworthy and effective organizer, which boosted his effectiveness as paralegal. This is also the reason why the few paralegals in the Justice for the Poor program who were also village heads received the largest number of cases: it was their position as village head that convinced villagers that he (or she) would succeed in settling their dispute.

A second, related factor is the strength of the network in which a paralegal is embedded. As contacts (with lawyers, the police, politicians, etc.) are crucial to solving issues, the development of a large network can greatly contribute to a paralegal’s effectiveness. Justice for the Poor’s paralegal project worked with local labor unions and agrarian organizations to select and train paralegals, and this seems to have helped paralegals to build trust and to acquire new useful contacts. Particularly the association with a local legal aid association is important for a paralegal as this constitutes his or her particular advantage over the other “legal intermediaries” mentioned earlier: this support from city-based lawyers signals to possible clients that a paralegal might actually succeed in bringing a case to court. A third factor influencing the number of cases paralegals received is their personal skills and savoir faire. The limited education and exposure of selected paralegals presents a great challenge to such community-based paralegal programs: while some showed extensive knowledge of the law and legal procedures and felt no hesitation about contacting power holders, there were many others who, even after being a paralegal for more than two years, lacked even basic legal knowledge and felt very shy about contacting a local police official or a village head. A self-reinforcing mechanism was at work here: because of a lack of skills and self-confidence, villagers did not ask a paralegal for help, which deprived this paralegal of the opportunity to develop the necessary self-confidence and skills.Footnote 36 This can be more difficult for women because of prevailing conservative ideas about the proper role of women in the public sphere – but this need not be an insurmountable obstacle, given the impressive female paralegals whom we encountered. The observed lack of skills and self-confidence of many paralegals points mainly to inadequacies in the training program, as the provided training seemed insufficient to turn many selected individuals into effective paralegals. In particular the training seemed inadequate to enable paralegals to engage in community organizing to address collective injustices. As we discuss in what follows, this is all the more regrettable as advocacy constitutes an area where paralegals could – compared to mediation and legal accompaniment – make a large contribution.

VII. Advocacy: A Fight for Electricity

Since March 2009 the ninety-eight families living in “Megaresidence,” a housing block in Bogor for low-income groups, had not been receiving electricity. The state electricity company, PLN, had found out that the electricity for the housing block had been illegally tapped, and it demanded a fine of Rp 89 million (about US$9,000) before it would reconnect the houses. According to the inhabitants, the developer had made this illegal connection to the electricity grid while reassuring the buyers of the houses that electricity was included.

As the developer was unwilling the pay the fine imposed by PLN, the inhabitants of Megaresidence approached a group of paralegals led by Mbak Sri. The paralegals threatened the developer with a lawsuit, who subsequently sent a group of preman (thugs) to intimidate inhabitants. While the paralegals did manage to document the wrongdoings of the developer, they calculated that any court case would be lengthy and possibly inconclusive; they opted for a different strategy. They staged several rallies, wrote letters to several governmental agencies, arranged newspaper coverage, and, using the contacts of the labor union for which they worked, Mbak Sri and the other paralegals convinced the members of “commission C” of the local parliament (DPRD) to conduct two hearings on the case. During this formal meeting DPRD members invited the different sides to tell their story; the whole community of Megaresidence came to the DPRD building for the occasion. Sri was afterward very proud of this moment: “this was an important moment because before the people could not meet officials and did not dare to speak publicly.” After the second hearing DPRD members issued (non-legally binding) advice, in which they instructed the developer to pay the fine while telling PLN to start providing electricity. At first PLN continued to press the inhabitants for payment of the fine, but after more media attention and the threat of a lawsuit the developer paid half the fine and PLN agreed to restart the provision of electricity. As Sri described her strategy: “We want to create synergy between the legal justice system and politics. We use politics to bring up the human side. We use it to touch the heart of government official. This is more effective … If we support a winning candidate, he can support us when we are working on a case.”

While strictly speaking this kind of activity might not be called “legal aid” – since it does not necessarily involve promoting access to legal systems – advocacy and community organizing is increasingly seen as an important part of the work of paralegals because these activities are often perceived (also by paralegals themselves) to be a more effective tool to address (mis)deeds by state institutions or companies than taking recourse to the formal justice system. This realization has led to calls to see legal empowerment and “social accountability” as two complementary strategies to achieve social justice.Footnote 37 In the campaign for an electricity connection, paralegals performed different roles: they offered legal advice, and they engaged in community organizing as well as lobbying. In the context of a slow and unpredictable justice system, political channels seem to offer effective alternative means to pressurize companies and state agencies. Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, local politicians have become more prominent as they are now elected and, after a decentralization process, also in control of more funds. Some of the studied paralegals – in our perception particularly the ablest ones – are seeing these increasingly prominent politicians as an effective channel to address injustices. As political parties in Indonesia generally lack a local base to facilitate interaction with citizens, paralegals are taking up this important liaising role.Footnote 38

The involvement of politicians can serve various purposes. First, the involvement of politicians, and particularly the organization of a public hearing, can be used to put pressure on the adverse party. The coverage of such a hearing can create negative publicity that shames the other party into agreeing to a settlement – that at least seemed to have been the reasoning of PLN. Another reason to involve politicians is that they can put pressure on the bureaucracy and the judicial apparatus. While there is a long history of political meddling in the bureaucracy and the judiciary, this meddling usually favored the privileged sections of society. But, as local politicians now need to maintain electoral support, it seems that in some cases local politicians show willingness and capacity to pressurize the police and other bureaucrats to defend the interests of the less well-connected and less moneyed party.

In this case, Mbak Sri cleverly employed the electoral concerns of politicians:

We have political contacts that we can use. We had to go almost every week to the DPRD building … During elections there is a “kontrak politik” with groups: we make the candidate promise that, if I am elected, he will do this and that. So in return KBB [the labor union of which Mbak Sri is a part] organizes an [election ]meeting with the candidate, where they give support.

In this case she could use this kontrak politik to get politicians to put pressure on the electricity company.

In all our research locations we encountered paralegals who had, like Shri, forged political links. Some had become members of the local campaign teams (Tim Sukses desa) of politicians, others made speeches during elections, and a third group just boasted of their friendships with politicians. Some of the paralegals said they maintained these political links because it would make them more effective paralegals – they reasoned that after elections they could ask the winning candidate for favors, calling it an investasi politik (“political investment”). For others it was also the other way around: they believe that by working as a paralegal they could raise their public profile and thus, in a later stage, become a politician themselves.

One can evaluate this use of political contacts both positively and negatively. On the one hand Indonesia’s democratization and decentralization processes have created new channels that can be used to pressurize disputing parties to reach a solution. The support from high-profile politicians is proving useful to help people to hold state institutions or companies accountable. On the other hand an increased role of political actors in dispute settlement is also creating situations where disputes are not settled on the basis of legal considerations, but on the basis of who is most capable of reciprocating (with votes or money) the support from politicians. The involvement of politicians in particular cases is not just motivated by considerations of justice; it is also motivated by a calculation about how this involvement can lead to votes and money. Compared to other Asian countries the capacity of DPRD members and other local politicians to pressurize civil servants is still limited, but there are indications that this capacity is growingFootnote 39 – where politicians can gain supporters and money by pressurizing the bureaucracy and the judiciary, they have an active interest in subverting bureaucratic procedures and, ultimately, the rule of law. These developments suggest that the prospects of improving access to justice are tied up with the way local political economies develop – particularly with the strategies that political elites are employing to hold on to power. This poses challenges for paralegal programs: while the employment of political contacts to settle issues is often very effective, it does stimulate politicians to develop their control over the bureaucracy and the judiciary – to the detriment of the rule of law. Paralegal training needs to address both the opportunities and the risks involved when associating oneself with politicians.

Given the effectiveness of paralegals in the case discussed here (as well as in other cases we studied) and given the lack of alternative actors and organizations to play such a role, advocacy played a surprisingly peripheral role in the studied paralegal programs. The number of cases involving state or corporate accountability is quite low – for example, less than 7 percent of the reported cases involved corruption and the provision of public services – and it seems that advocacy skills were not sufficiently trained – interviewed paralegals state that they hardly received training on political lobbying, organizing rallies, getting media attention, etc. Furthermore, the design of the World Bank and UNDP projects influenced the number of advocacy cases paralegals receive: by choosing to train villagers to work as paralegals within their community, it remains accidental whether they run into cases involving state or corporate accountability. It depends on whether such a case happens to present itself. In most villages there are only small village-level disputes to work on – which are also dealt with by local mechanisms. This is a drawback of working with community-based paralegals in this way: by selecting project areas that are known to be involved in supra-local disputes with companies or state agencies, or by training paralegals to move around and work in different villages, paralegals could become more regularly involved in such supra-local disputes and advocacy campaigns against corporate or governmental malpractices. This could improve the overall contribution of paralegal projects.

VIII. Conclusion

In this chapter we discussed the impact of the presence of paralegals on grievance and dispute handling in rural Indonesia. Focusing on the paralegal projects supported by UNDP and the World Bank, we discussed the three main spheres of activities of paralegals: mediation, legal accompaniment, and advocacy. Deriving inspiration from relational sociology, we argued that the impact of the presence of paralegals does not lie so much in improving the access to the formal legal system, but rather in countering the impact of power imbalances between disputing parties on the outcome of processes of grievance and dispute handling. The presence of paralegals does not necessarily lead to a large number of cases being referred to the formal legal system – the widespread distrust of the formal legal system combined with the availability of local mechanisms also often discourages paralegals themselves to advise such legal action. This might be different in the long run: although difficult to substantiate, we found some indications that the way paralegals familiarize their fellow villagers with Indonesian law could in the long run serve to overcome this avoidance of the Indonesian legal system. But in the short run the impact of paralegals lies mainly in enlarging the shadow of the law as they do insert legal considerations more forcefully into mediation (and advocacy) processes, and in this manner paralegals strengthen the bargaining position of their clients.

Not every paralegal has the capacity to do so, however. Paralegals compete with other local actors for the status (and money) involved in solving disputes and addressing grievances, as various actors and local institutions can be found who perform similar tasks. We observed that the role of paralegals during mediation processes is often modest, as these sessions are usually led by village heads or customary leaders with paralegals in an advisory role. Various “legal intermediaries” – ranging from village heads to case brokers, bodrex NGOs, and local preman – could be identified who are also engaged in dispute settlement and in the facilitation of the interaction with the police and the courts. The competition with these various other legal intermediaries can limit the effectiveness of paralegals and forms an obstacle for gaining trust among the local population.

It is unfortunate that one area of work where paralegals do offer unique skills – advocacy – plays a marginal role in the studied programs. Those paralegals who possessed advocacy skills proved highly effective in helping communities deal with government or corporate malpractices. As political parties in Indonesia’s young democracy are generally very weakly institutionalized, paralegals are playing an important role as liaisons between local communities and politicians. Since decentralization and the institution of local elections are making local politicians more prominent, many paralegals now feel that a strong political lobby can be more effective than legal action. For this reason some paralegals are carefully nurturing their political contacts, which often stimulates them to campaign for candidates during elections. While this capacity to engage with politics boosts the effectiveness of paralegals, this engagement also carries risks – particularly that this engagement can go against the stated aim of paralegal projects to strengthen the rule of law.

Paralegalism in Indonesia is as yet still weakly institutionalized. The paralegal programs currently operative in Indonesia are set up by a limited group of universities, Indonesian legal aid organizations, and international donors. Efforts to institutionalize the accreditation of paralegals are still in its infancy. Unfortunately the recently adopted Legal Aid Bill did little to change that, as its efforts as well as funding have largely concentrated on supporting representation in court. Yet the need for legal aid beyond the courts is as big as ever. Conflicts arising out of, for example, the relentless expansion of palm oil companies and Indonesia’s vague land regime, as well as the recent empowerment of village heads (through the new village law), are having a big impact on people’s livelihoods. Many more paralegals are needed to address such conflicts and find fairer outcomes as they can help to tackle the impact of social inequalities within Indonesian society on processes of dispute resolution. Operating at the crossroads between law, social norms, and power relations, paralegals can contribute to making the outcomes of these processes more equitable.