Book contents

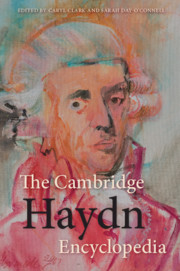

- The Cambridge Haydn Encyclopedia

- The Cambridge Haydn Encyclopedia

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Music Examples

- Contributors

- Preface and Guide to Readers

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Abbreviations

- List of Entries and Essays

- Dictionary

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index of Compositions

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 April 2019

- The Cambridge Haydn Encyclopedia

- The Cambridge Haydn Encyclopedia

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Music Examples

- Contributors

- Preface and Guide to Readers

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Abbreviations

- List of Entries and Essays

- Dictionary

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index of Compositions

- References

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Haydn Encyclopedia , pp. 407 - 450Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019