6.1 Introduction

The preceding chapters raise three issues that are crucial to understanding the politics of healthy ageing. First, older voters are not as powerful nor as unified as many politicians, think tanks and commentators often believe. While some elderly voters have preferences for policies that are in their own interests or in the interests of their children and grandchildren, older voters are not sufficiently homogeneous to act as a voting bloc. Indeed, even if they were, it is not clear that their influence on policy would be substantial because policy decisions are not simply determined by voters’ demand. Second, in those few contexts where political conflict over policies is framed intergenerationally, the wellbeing of older people can be preserved without being at the expense of other groups, particularly those of working age. Reframing the debate in this way helps societies move from policies which individualize the responsibility of being healthy – by withdrawing government investment – to an emphasis on healthy ageing which seeks to establish cross-class/cross-generational coalitions. Third, inequalities in healthy ageing are structured according to other kinds of inequality in the social determinants of health, and these upstream inequalities are best understood when situated in a life-course perspective which recognizes that inequalities in ageing are the product of inequalities that manifest at much earlier stages in life. Not everybody gets to be old.

One implication that flows from this analysis is that the ‘ageing crisis’ and the political narrative that has gone along with it (‘grey electoral power’) has become so pervasive that it is altering the supply side of policy options. That is, when politicians, civil servants and think tanks begin to consider policy options within the constraints of the ‘ageing crisis’ narrative, then countries may become more likely to implement policies to protect older voters but which, ironically, undermine healthy ageing. This can happen even in countries where older people themselves are not necessarily advocating for these reforms. Rather, the discourse around these issues has become so pervasive that it creates the conditions in which ‘win-lose’ policies become more likely.

The argument of this chapter is that these ‘win-lose’ policies harm health among younger citizens and, in so doing, these same policies paradoxically contribute to the health problems of an ageing population. This is because ageing is not costly per se. Rather, getting older only increases costs if those older people are in poorer health. We illustrate the problem of win-lose policies in terms of improving healthy ageing via reducing health inequalities through exploring a series of case studies which illustrate the health effects of win-win or win-lose policies. To be clear, we are not arguing that these policies were implemented as a result of intergenerational conflict (this has been discussed in Chapters 3 and 4). Rather, we take examples of the kind of win-win and win-lose policies described in the introduction to illuminate how they affect health and healthy ageing.

6.2 Win-Win Policies and Healthy Ageing

Inequalities in health are not only pervasive, as we have discussed. They also seem remarkably durable (Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2017; Reference ReevesReeves, 2017b). Indeed, one of the key debates in public health and allied fields is whether achieving reductions in health inequalities is possible through government intervention. This debate has crucial implications for inequalities in healthy ageing and whether win-win policies could minimize the economic risks associated with the ageing crisis. One of the great disappointments of public health is that health inequalities seem to persist in high-income countries despite substantial improvement in living standards, the creation of welfare states and concerted government efforts to reduce such disparities (Reference Hu, van Lenthe and JudgeHu et al., 2016; Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2012). Professor Johan Mackenbach has, in recent years, struck a more pessimistic note than many in the field, arguing that ‘reducing health inequalities is currently beyond our means’ (Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2010). Many do not agree with him, however. Professor Sir Michael Marmot, for example, is far more optimistic. His recent book lays out the evidence behind health gaps around the world but it also argues that these in equalities are not only avoidable but that ‘we know what to do to make a difference’ to health inequalities (Reference MarmotMarmot, 2015). In other words, societies can address inequalities in healthy ageing and they know how to do it – they just need the political will to do so (Reference BambraBambra, 2016). This does not mean that reducing health inequalities across the life-course is straightforward, but this section examines two examples of how health inequalities have been successfully reduced through policies which embody ‘win-win’ approaches to the ageing crisis. We begin with the English health inequalities strategy (2000–2010) and then turn to a rather unusual example of win-win policies by examining Germany post-Reunification (1990–2010) in order to draw lessons for other European countries.

6.2.1 The English Health Inequalities Strategy as a Win-Win Strategy

In 1997 a Labour government was elected in England on a manifesto that included a commitment to reducing health inequalities. This led to the implementation between 2000 and 2010 of a wide-ranging and multi-faceted health inequalities reduction strategy for England (Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2010) in which policymakers systematically and explicitly attempted to reduce inequalities in health. The strategy focused specifically on supporting families, engaging communities in tackling deprivation, improving prevention, increasing access to health care and tackling the underlying social determinants of health (Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2010). For example, the strategy included large increases in levels of public spending on a range of social programmes, the introduction of the national minimum wage, area-based interventions such as the Health Action Zones and a substantial increase in expenditure on the health care system (Reference Robinson, Brown and NormanRobinson et al., 2019). The latter was targeted at more deprived neighbourhoods when, after 2002, a ‘health inequalities weighting’ was added to the way in which National Health Service (NHS) funds were geographically distributed, so that areas of higher deprivation received more funds per head to reflect higher health need (Reference BambraBambra, 2016). Furthermore, the government also made tackling health, social and educational inequalities a public service priority by setting public service agreement targets. The key targets of the Labour government’s health inequalities strategy were to: (1) reduce the gap in life expectancy at birth between the most deprived local authorities and the English average by 10 per cent by 2010; and (2) cut inequalities in the infant mortality rate by 10 per cent by 2010.

Part of Mackenbach’s scepticism was rooted in an early analysis of England’s efforts to reduce health inequalities following the election of New Labour in 1997. Those papers suggested the strategy had not delivered the expected results (Reference Hu, van Lenthe and JudgeHu et al., 2016), concluding ‘if this did not work, what will’? (Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2010). However, more recent empirical examinations of this investment has suggested that these reforms did reduce inequalities, at least geographical inequalities in health (Reference Barr, Bambra and WhiteheadBarr et al., 2014; Reference Barr, Higgerson and WhiteheadBarr et al., 2017; Reference Buck and MaguireBuck & Maguire, 2015; Reference Robinson, Brown and NormanRobinson et al., 2019). What is particularly striking about these analyses is that they suggest the reversal of these policies, which largely occurred following the implementation of austerity in the UK, actually stopped progress towards reducing health inequalities and may have even led to them increasing.

Recent empirical studies have found that the strategy was partially effective. Reference Barr, Higgerson and WhiteheadBarr et al. (2017) found that geographical inequalities in life expectancy declined during the English health inequalities strategy period, reversing a previously increasing trend. Before the strategy, the gap in life expectancy between the most deprived local authorities in England and the rest of the country increased at a rate of 0.57 months each year for men and 0.30 months each year for women. During the strategy period this trend reversed, and the gap in life expectancy for men declined by 0.91 months each year and for women by 0.50 months each year. Reference Barr, Higgerson and WhiteheadBarr et al. (2017) also found that since the end of the strategy period the inequality gap has increased again at a rate of 0.68 months each year for men and 0.31 months each year for women. At the end of the English health inequalities strategy period, the gap in male life expectancy was 1.2 years smaller and the gap in female life expectancy was 0.6 years smaller than would have been the case if the trends in inequalities before the strategy had continued.

Further, Reference Robinson, Brown and NormanRobinson et al. (2019) investigated whether the English health inequalities strategy was associated with a decrease in geographical inequalities in infant mortality rate. They found that before New Labour’s health inequalities strategy (1983–98), the gap in the infant mortality rate between the most deprived local authorities and the rest of England increased at a rate of 3 infant deaths per 100,000 births per year. During the strategy period (1999–2010) the gap narrowed by 12 infant deaths per 100,000 births per year and after the strategy period ended (2011–17) the gap began increasing again at a rate of 4 deaths per 100,000 births per year. This is shown in Figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Trends in absolute inequalities in infant mortality rate (IMR), 20 per cent most deprived local authorities compared to the rest of England, 1983 to 2017.

Another area of strategy success was around reducing geographical inequalities in mortality amenable to health care, which is defined as mortality from causes for which there is evidence that they can be prevented given timely and appropriate access to high quality care (Reference Nolte and McKeeNolte & McKee, 2011). NHS funding was increased from 2001 when the aforementioned ‘health inequalities weighting’ was added to the way in which NHS funds were geographically distributed to target funding to areas of higher deprivation. Analysis has shown that this policy of increasing the proportion of resources allocated to deprived areas as compared to more affluent areas was associated with a reduction in absolute health inequalities from causes amenable to health care (Reference Barr, Bambra and WhiteheadBarr et al., 2014). Increases in NHS resources to deprived areas accounted for a reduction in the gap between deprived and affluent areas in male ‘mortality amenable to health care’ of 35 deaths per 100,000 and female mortality of 16 deaths per 100,000. Each additional £10 million of resources allocated to deprived areas was associated with a reduction in 4 male deaths per 100,000 and 2 female deaths per 100,000 (Reference Barr, Bambra and WhiteheadBarr et al., 2014).

Thus, the most recent data show that the English strategy did reduce health inequalities in terms of life expectancy, infant mortality rates and mortality amenable to health care. So, what does New Labour’s experience teach us about reducing health inequalities? First, investing in good services in deprived areas (Reference Barr, Higgerson and WhiteheadBarr et al., 2017), the creation of programmes which support young families, such as Sure Start (Reference Sammons, Hall and SmeesSammons et al., 2015), reducing child poverty whilst protecting older households, and ensuring low-wage workers get paid a decent wage (Reference Reeves, McKee, Mackenbach, Whitehead and StucklerReeves et al., 2017a) all seemed to improve health and may have contributed to the reduction in health inequalities.

However, it has to be acknowledged that the decreases were on the modest side. Arguably, the English health inequalities strategy may have been even more effective in reducing health inequalities if there had not been a gradual ‘lifestyle drift’ in governance – whereby policy went from thinking about the social determinants of health alongside behaviour change, to focusing almost exclusively on individual behaviour change (Reference Whitehead and PopayWhitehead & Popay, 2010). Only so much can be achieved in terms of reducing health inequalities by focusing only on individual-level behaviour change (a form of ‘win-lose’ policy) or the provision of treatment services such as smoking cessation programmes or by increasing access to health care services. There is a need to also address the more fundamental social and economic causes. Whilst some policies enacted under the 1997–2010 Labour governments focused on the more fundamental determinants (e.g. the implementation of a national minimum wage, the minimum pension, tax credits for working parents, and a reduction in child poverty), as well as significant investment in the health care system, there was, however, little substantial redistribution of income between rich and poor (Reference LynchLynch, 2020). Nor was there much by way of an economic rebalancing of the country (e.g. between north and south). Further, in wider policy areas the Labour governments continued the neoliberal approach of Thatcherism, including, for example, further marketization and privatization of the health care system (Reference Scott-Samuel, Bambra and CollinsScott-Samuel et al., 2014). The strategy may also have been even more effective if it had been sustained over a longer time period. But the global financial crisis of 2007–8 led to the premature end of the English health inequalities strategy, a change of governing political party and an increase again in health inequalities (Taylor-Reference Taylor-Robinson, Lai and WickhamRobinson et al., 2019).

So, the lessons we learn from England’s strategy are only relevant to a particular vision of what society could be. The Labour governments of 1997–2010 did not fundamentally try to alter the political economy of society but rather to harness the two impulses of both neoliberalism and progressive politics. Their approach was to ‘let the market rip’ and then use taxes and transfers to redistribute wealth to those communities not benefiting from the explosion of growth (Reference LynchLynch, 2020). They did not attempt to pursue more radical policies that would fundamentally reorganize society, for example by shifting the mode of capitalism that dominates within the UK (Reference Hall and SoskiceHall & Soskice, 2001). It is, of course, very difficult to make such radical leaps from one type of political economy to another, as economic and political institutions are path dependent (Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt, Kriesi, Beramendi, Hausermann, Kitschelt and KriesiBeramendi et al., 2015). But what Labour’s experience cannot tell us is what would have happened had they tried to do so. This is, in fact, where Mackenbach’s basic pessimism comes from: he is profoundly sceptical that such radical breaks from one political-economic arrangement to another are politically feasible. However, this does overlook the emergence of powerful narratives that have enabled countries to embark on radical reforms that reduced inequality – such as in post-war Britain and Europe with the setting-up of the welfare state and free, universal health care (Reference Scheve and StasavageScheve & Stasavage, 2016).

6.2.2 German Reunification: Drawing Lessons from an Unusual Win-Win

There is another dimension to debates about what will work to improve healthy ageing and reduce health inequalities that it is important to stress, and that is the issue of time. Mackenbach is also attuned to this when he acknowledges that health inequalities are the result of the cumulative impact of decades of exposure to health risks, some of them intergenerational, of those who live in socioeconomically less advantaged circumstances (Reference MackenbachMackenbach, 2010). Inequalities within age-groups, including among the elderly, are not solely the product of current practices and a contemporary socioeconomic position. Rather, habits of consumption over many years both reflect and interact with exposure to sustained economic conditions that structure our lives to generate health inequalities (Reference BartleyBartley, 2016).

This comes through in life-course research which has repeatedly observed that the conditions into which children are born and then raised cast a long shadow over their health for the rest of their lives (Reference Ben-Shlomo and KuhBen-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002). Children born into lower socioeconomic positions have poorer physical capabilities in later years; for example, they have slower walking speeds and find it more difficult to get out of a chair (Reference Birnie, Cooper and MartinBirnie et al., 2011). While such reduced mobility is a negative health outcome in and of itself, these measures are also highly predictive of future mortality rates too (Reference Kuh, Karunananthan, Bergman and CooperKuh et al., 2014). Birth weight is positively related to grip strength (Reference Kuh, Karunananthan, Bergman and CooperKuh et al., 2014) and grip strength also predicts mortality (Reference Celis-Morales, Welsh and LyallCelis-Morales et al., 2018). Crucially, birth weight is influenced by the generosity of the welfare state (Reference Strully, Rehkopf and XuanStrully et al., 2010).

This is not just about childhood. Living in poor quality housing for many years has an additional negative impact on your health over and above the influence of living in poor quality housing today (Reference Pevalin, Reeves, Baker and BentleyPevalin et al., 2017). Neighbourhoods too have a scarring effect on health. Living in a deprived neighbourhood during your adult life increases your allostatic load in adulthood, even after accounting for your own personal living conditions (Reference Gustafsson, San Sebastian and JanlertGustafsson et al., 2014).

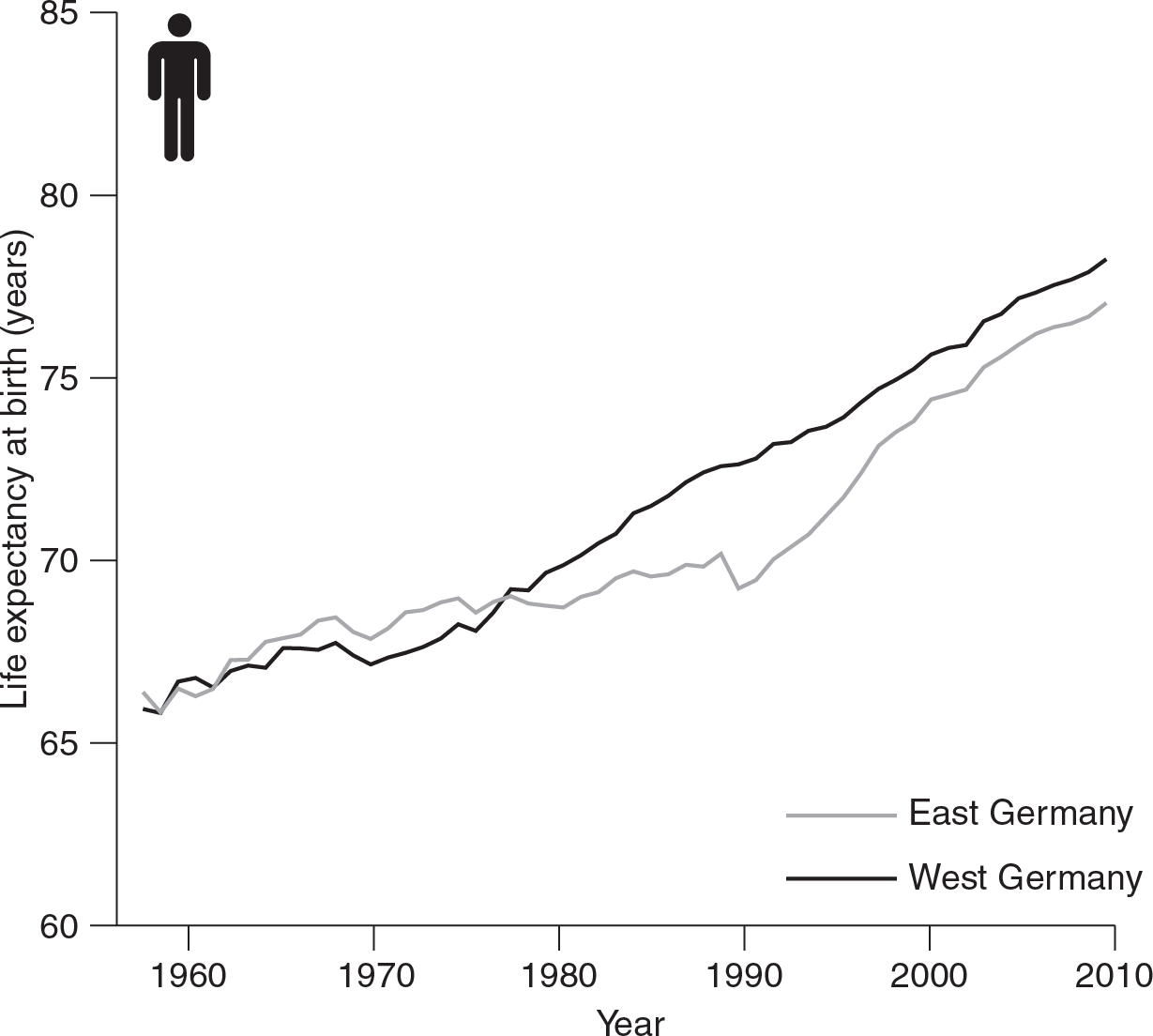

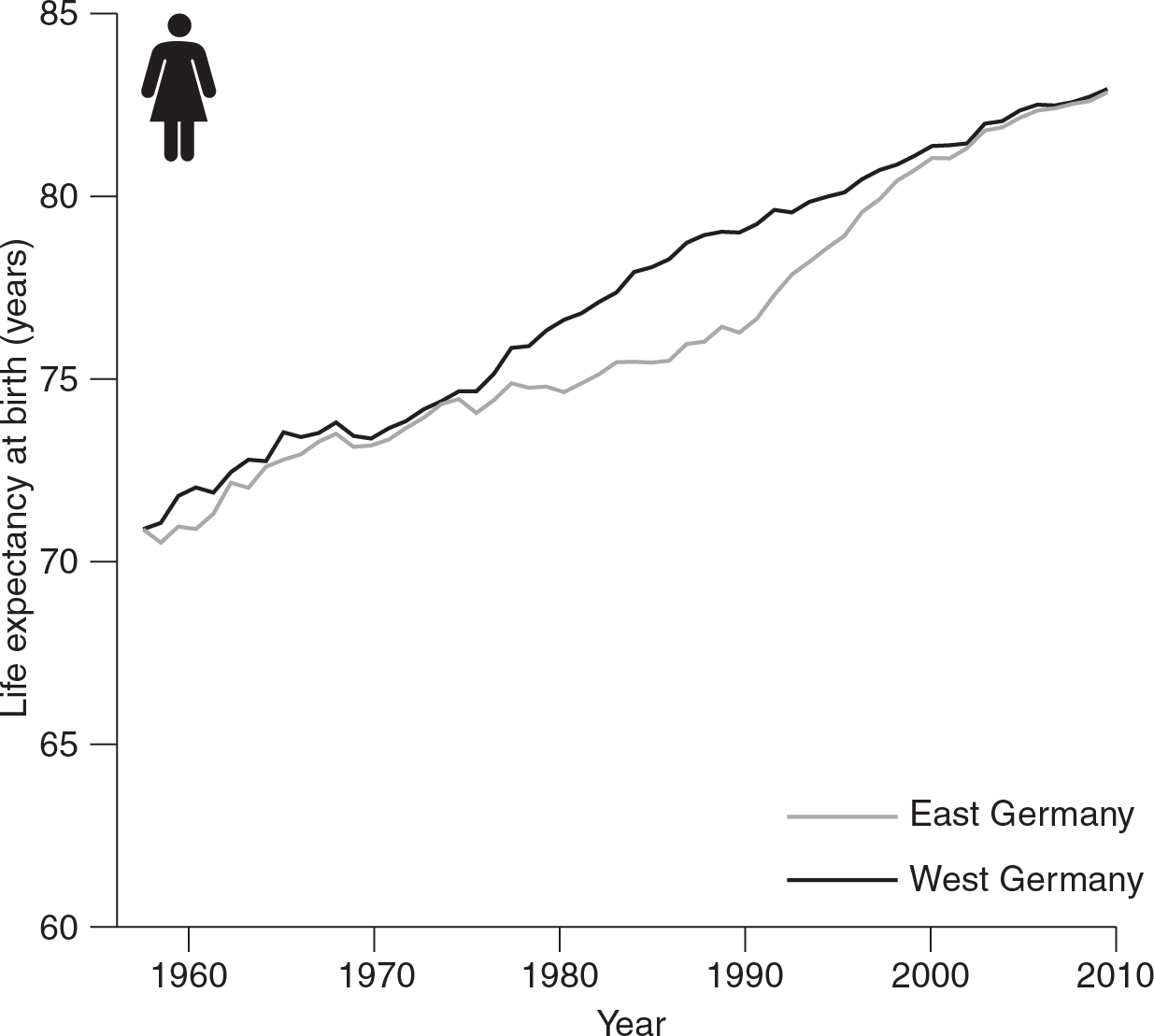

As Professor Ted Schrecker has argued, addressing health inequalities will require a substantial redistribution of resources, but it will also require time (Reference SchreckerSchrecker, 2017). The example of German Reunification provides an example of reductions in regional health inequalities over a twenty-year period. In 1989 – before the fall of the Berlin Wall – there was a four year life expectancy gap between East and West Germany. But this East-West gap rapidly narrowed in the following decades so that by 2010 it had dwindled to just a few months for women and just over six months for men (Figures 6.2 and 6.3) (Reference Bambra, Barr and MilneBambra et al., 2014; Reference BambraBambra, 2016). So, how was this done?

Figure 6.2 Trends in male life expectancy in Former East and West Germany to 2010.

Figure 6.3 Trends in female life expectancy in Former East and West Germany to 2010.

First, the living standards of East Germans improved with the economic terms of the Reunification whereby the West German Deutsche Mark (a strong internationally traded currency) replaced the East German Mark (considered almost worthless outside of the Eastern bloc) as the official currency – a Mark for a Mark. This meant that salaries and savings were replaced equally, one to one, by the much higher value Deutsche Mark. Substantial investment was also made into the industries of Eastern Germany and transfer payments were made by the West German government to ensure the future funding of social welfare programmes in the East. This meant that by as early as 1996, wages in the East rose very rapidly to around 75 per cent of Western levels from being less than 40 per cent in 1990 (Reference Kibele, Klüsener and ScholzKibele et al., 2015). This increase in incomes was also experienced by old age pensioners. In 1985 retired households in the East had only 36 per cent of the income of employed households, whilst retirees in the West received 65 per cent (Reference Gjonca, Brockmann and MaierGjonca et al., 2000). After Reunification the West German pension system was extended into the East which resulted in huge increases in income for older East Germans: in 1990 the monthly pension of an East German pensioner was only 40 per cent of that a Western pensioner, but by 1999 it had increased to 87 per cent of West German levels (Reference Gjonca, Brockmann and MaierGjonca et al., 2000). This meant that retired people were one of the groups that benefited most from Reunification, particularly East German women as they had, on average, considerably longer working biographies than their West German counterparts (Reference Gjonca, Brockmann and MaierGjonca et al., 2000).

Secondly, access to a variety of foods and consumer goods also increased as West German shops and companies set up in the East. It has been argued that this led to decreases in cardiovascular diseases as a result of better diets (Reference Nolte, Scholz, Shkolnikov and McKeeNolte et al., 2002). It was not all Keynesianism for the ‘Ossis’ (Easterners), though, as unemployment (unheard of in the full employment socialist system) also increased as a result of the rapid privatization and de-industrialization of the Eastern economy and, indeed, unemployment still remains nearly double that of the West today. A special solidarity surcharge had, however, been introduced to fund economic improvements. This was levied at a rate of up to 5.5 per cent on income taxes owed across both East and West (e.g. a tax bill of €5,000 attracts a solidarity surcharge of €275) (Reference Gokhale, Raffelhüschen and WalliserGokhale et al., 1994).

Thirdly, immediately after Reunification considerable financial support was given to modernize the hospitals and health care equipment in the East, and the availability of nursing care, screening and pharmaceuticals also increased. This raised standards of health care in the East so that they were comparable to those of the West within just a few years (Reference Nolte, Scholz, Shkolnikov and McKeeNolte et al., 2002). This had notable impacts on neonatal mortality rates and falling death rates from conditions amenable to primary prevention or medical treatment (Reference Nolte, Scholz, Shkolnikov and McKeeNolte et al., 2002).

Both the economic reforms and the increased investment in health care were the result of the deep and sustained political decision to reunify Germany as fully as possible so that, as Chancellor Kohl stated, ‘what belongs together will grow together’. Germany’s lessons for reducing health inequalities and reducing unequal ageing are therefore two-fold: firstly, even large health inequalities can be significantly reduced, over time; secondly, the tools to do this are largely economic but – crucially – within the control of politics and politicians. Ultimately, the German experience shows that if there is sufficient political desire to reduce unequal ageing, it can be done. It shows the primacy of politics and economics, underlying the need for a political dimension to our understanding of how to reduce health inequalities.

And yet, despite the case study evidence in favour of investing in social protection and creating institutions which ensure a more equitable distribution of both wealth and opportunity, there are reasons to be cautious about simply extrapolating from these two country case studies. The same intervention will not work the same everywhere because it will inevitably interact with pre-existing conditions and attitudes, and the outcomes are not straightforwardly predictable. We certainly have some good evidence that particular reforms have improved (or aggravated) health inequalities in some contexts, but what is less clear is whether we can take those reforms to other countries and deliver the same results.

6.3 Win-Lose Policies and the Implications for Healthy Ageing

Win-win policies may reduce health inequalities, but this does not necessarily mean that win-lose policies make them any worse. This is in part because the distinction between high- and win-lose is not necessarily just a question of ‘treatment’ intensity and so we cannot think about the association between government policy and health inequalities as a simple dose-response relationship. In part, this is because there are likely to be all kinds of non-linearities and spill-over effects which will play out differently in win-win and win-lose contexts. Indeed, if win-win contexts are places where policies are coherently pulling towards a life-course approach to ensuring healthy ageing, then win-lose contexts may be precisely the kinds of places where incoherent policies are pulling in different directions and thereby make some inequalities worse but others better, with little overall change in general population. In these win-lose settings, the marginal influence of government may simply be quite small. Of course, if Marmot is right – that health inequalities are avoidable and we know how to avoid them – then win-lose policies may indeed exacerbate the gaps in health outcomes between the privileged and the deprived. This section again explores these issues through two ‘win-lose’ policy case studies: austerity in the UK and the Americanization of European economies. Both of them are rooted in liberal market economies in part because these are places where win-lose policies have been implemented but also because these are sites where politicians have perceived the electoral power of older votes to be large (even if in practical terms it has not been as substantial as many might have thought). These cases are examples of countries where win-lose policies have been pursued in light of – albeit perhaps not directly caused by – the narrative around the ageing crisis.

6.3.1 Austerity Politics and Ageing in the UK

We start again with the UK because it is such a crucial case. Not only is the UK an example of an attempt to pursue win-win policies, but the pursuit of austerity policies over the last decade (2010–20) provides some hints at how failing to take the win-win may create long-term health challenges that could affect the ageing process. Stagnating life expectancy in the UK, for example, has been driven by a mix of rising mortality among both the elderly and, more surprisingly, those of working age (PHE, 2018). Perhaps more striking, inequalities in life expectancy have tragically risen in the last few years, according to recently released figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2019). There are also signs that inequalities in infant mortality rates may also be increasing – particularly in areas that have experienced the greatest increases in child poverty (Taylor-Reference Taylor-Robinson, Lai and WickhamRobinson et al., 2019). This is not only because of greater improvements among the better-off but because the poorest have also experienced real declines. In the most deprived parts of England, female life expectancy at birth fell by almost 100 days between 2012 and 2017. Men in the poorest areas saw no improvements while those in the richest parts of the UK continued to see their life expectancies improve. This will have implications for inequalities in ageing into the future.

Given our arguments above, falling life expectancy is not entirely unexpected. Indeed, part of the explanation of these unprecedented changes may be rooted in economic reforms implemented in the UK since the economic crisis. As a political response to the 2007–8 financial crisis, the 2010 Conservative-led coalition government pursued a policy of austerity, characterized by a drive to reduce public deficits via large-scale cuts to central and local government budgets, reduced funding for the health care system, and large reductions in welfare services and working-age social security benefits. These changes appear to be increasingly linked to rising geographical inequalities and health inequalities (Reference PearcePearce, 2013). While the government boasted about record levels of employment, we have seen the quality of work and wage levels decline. The number of children living in absolute poverty rose by 200,000 between 2016–17 and 2017–18, and risks hitting record levels (Reference RichardsonRichardson, 2019). In-work poverty continues to rise. The proportion of poor who live in working households has never been higher (70 per cent), and the face of poverty is getting younger too: 53 per cent of poor children are under the age of 5. Living standards actually fell last year. This is not remotely normal; it means families have been left struggling to afford to heat their homes, feed their families and even access health care (Reference Loopstra, Reeves and StucklerLoopstra et al., 2015; Reference Reeves, McKee and StucklerReeves et al., 2015).

Austerity has been central to these changes. Cuts to housing benefit have meant households have not been able to respond to the rising cost of housing and the benefits freeze has slowly undermined the generosity of social security payments (Reference BarnardBarnard, 2019; Reference Reeves, Clair, McKee and StucklerReeves et al., 2016). The punitive sanction regime and the draconian implementation of working capability assessments have both created destitution, pushed people onto antidepressants and may have even induced higher suicide rates (Reference Barr, Taylor-Robinson and StucklerBarr et al., 2016; Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann, Reeves and StucklerLoopstra et al., 2018).

Take the benefits freeze. Since 2016 the value of social security payments has been fixed at 2015 prices. This freeze has affected more than 27 million people, and swept around 400,000 into poverty (Reference BarnardBarnard, 2019). Unable to deal with the rising tide of higher prices, low-income families are, on average, £340 a year worse off than they would have been. This has been one of the costliest aspects of austerity, but we are only just starting to see the effects of this change in health data because the latest figures on inequalities in life expectancy come from 2015–17, the very start of the freeze.

Alongside the benefits freeze, we are still in the middle of the roll-out of Universal Credit. The Work and Pensions Committee have pointed out ‘fundamental flaw[s] in the benefit’s design’ which may lead to a ‘human and political catastrophe’ (Reference Keen, Kennedy and WilsonKeen et al., 2017). Emerging evidence suggests Universal Credit has created homelessness, hunger and destitution (Reference HayHay, 2019; Reference Jitendra, Thorogood and Hadfield-SpoorJitendra et al., 2018). Moreover, we are still waiting for the most significant change, bringing all current recipients of tax credits onto the programme (~7 million people in total when it is complete) (Reference HillsHills, 2014). Particularly concerning is the high rate of sanctions faced by those on Universal Credit (up to 7 per cent of claimants every month). When sanctions were deployed at high rates under the Job Seekers Allowance, it merely pushed people away from the labour market, leaving them to rely on informal forms of support (Reference Loopstra, Reeves and StucklerLoopstra et al., 2015; NAO, 2016; Reference ReevesReeves, 2017a).

The UK’s austerity measures tended to focus on people of working age, leaving pensioners in a better position than ever, through a series of reforms that ensured growth in the value of the state pension (Reference Akhter, Bambra, Mattheys, Warren and KasimAkhter et al., 2018). But the elderly were not protected in every country. Due to population ageing, pensions have become one of the largest single areas of public expenditure in high-income countries. It is unsurprising therefore that governments around Europe used this moment to reconfigure pension schemes to cut spending on the elderly. Shortly after austerity began to spread, the OECD expressed concern that proposed cuts to pensions would only harm the financial security of the elderly. Many countries went ahead anyway: Czechia and Norway altered indexation rules to reduce spending over the long term, while Greece and Hungary took a more immediate approach, implementing fairly stark reductions in the value of payments. These changes have not been benign either, and have led to increases in unmet medical need among the elderly, particularly for those who were already at the bottom of the income distribution. Reductions in European state pensions have widened inequalities in access to social care, and this may be partially behind the excessive fatalities amongst most deprived groups linked to the coronavirus epidemic that has ravaged elderly populations across the continent (see Chapter 5, Section 2.7).

In the area of health care, Britain’s approach to the NHS provides an intriguing case. It did not increase co-payments but neither did it expand services. Instead, spending on health was ‘ring-fenced’ by the Conservative-led coalition government, and this in the context of major reductions in spending almost everywhere else. And yet, this ring-fence created the most sustained decline ever in NHS spending as a percentage of GDP, simultaneously producing the most financially difficult decade for the NHS since its inception. American political scientist Jacob Hacker calls such changes ‘policy drift’, when the maintenance of the status quo slowly stops it from adapting to shifting social conditions and changing risks. Over the last few winters the NHS has increasingly struggled to cope with the demands placed upon it. The coronavirus pandemic has provided a stark example of how long-term underfunding has impacted on the health care system, with all health care providers cancelling all non-essential surgeries, leading to immense backlogs and waiting lists, and arguably contributing to excess non-coronavirus deaths – especially in more deprived neighbourhoods (Reference Bambra, Riordan, Ford and MatthewsBambra et al., 2020; Reference Bambra, Lynch and SmithBambra et al., 2021). Subsequently, the mortality rate in the first quarter of 2018 was the highest since 2009.

Elderly people are one of the groups most reliant on effective health and social care services. When these services break down, the elderly will suffer, and these data suggest that some of the most vulnerable – that is, the oldest old – have indeed been left exposed. These real-term reductions in public expenditure on social care associated with austerity policies in the UK were associated with higher mortality rates among the elderly, especially those in care homes – precisely those groups who seem to be driving the slow-down in improvements in life expectancy in the UK. This is especially tragic because a muddled plan to address the deficit in social care spending during the 2015 UK general election missed an opportunity to address this crisis, leaving many elderly people exposed to inadequate social care and, all too often, shorter lives – especially given the particular vulnerability of the over-80s to respiratory conditions, including the coronavirus pandemic.

Austerity is a ‘slow train coming’; an unfolding crisis that is only now becoming visible in the published data, and it is interacting with and exacerbating the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic (Reference Bambra, Riordan, Ford and MatthewsBambra et al., 2020). The true impact of austerity goes well beyond the most immediate health consequences because of its impact on material deprivation driven by cuts to social protection and other social services, including health systems. Poverty harms health, but the implications may not manifest themselves in the same year or even in the year after. Poverty has a scarring effect on health, but it may take some time for these scarring effects to show up as higher rates of mortality. In part, this is because austerity has powerful supporters. Many countries are still waiting to implement, or at least implement fully, austerity measures announced some years ago. The restructuring of welfare states in response to the 2007–8 global financial crisis and now the coronavirus economic depression is ongoing.

6.3.2 Health Inequalities and the “Americanization” of European Political Economy

Stalling life expectancy in Europe is closely linked with higher mortality among the elderly, while in the USA rising mortality rates have been most striking among people of working age (Reference Case and DeatonCase & Deaton, 2015). Unsurprisingly, the causes of death have been quite different too, mainly suicides and drug overdoses in the USA – what Case and Deaton call ‘deaths of despair’ (Reference Case and DeatonCase & Deaton, 2015). Many of these deaths are clearly not the product of the Great Recession alone, nor of any systematic state retrenchment in response to the financial crisis. With austerity, European countries are, in many instances, merely emulating the neoliberal economic and welfare reforms already implemented in the USA in the 1980s and 1990s, which also reduced the generosity of welfare and increased conditionality. European countries such as the UK and Germany are now witnessing stagnating wages, something Americans have lived with for almost thirty years. So, what are the implications of the Americanization of European political, welfare and economic systems for the future of healthy ageing?

It is well established that the USA has a significant mortality disadvantage relative to other wealthy countries – with, for example, life expectancy rates that are more than three years less than France and Sweden (Reference Avendano and KawachiAvendano & Kawachi, 2014) and growing mortality and morbidity rates, particularly amongst middle-aged, low income Whites (Reference Case and DeatonCase & Deaton, 2015). It also has higher health inequalities – particularly in terms of ethnicity and income (Reference BambraBambra, 2019). These can be explained through the political economy of the USA.

One political economy mechanism behind the worse health of the USA is through the relatively limited regulation of unhealthy products, such as tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food and drinks, and the industries that produce and market these products (Reference FreudenbergFreudenberg, 2016). The USA is one of the least regulated markets among high income countries, and is one of only a small number of high income countries not to have ratified the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHOon, 2003). These various political and economic factors interact to shape the health of Americans unevenly, contributing to the country’s extensive health inequalities (Reference Krieger, Kosheleva and WatermanKrieger et al., 2014). Geographical work has shown that tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed foods tend to be highly available in low income urban areas of the USA, and that the products are increasingly targeted at, and available to, low income and minority populations – thereby shaping the local context within which health inequalities arise (Reference Beaulac, Kristjansson and CumminsBeaulac et al., 2009).

A second mechanism is through higher rates of poverty in the USA compared to most of Europe. The state provision of social welfare is minimal in the USA, with modest social insurance benefits which are often regulated via strict entitlement criteria, with recipients often being subject to means-testing and receipt, accordingly, being stigmatized (Reference BambraBambra, 2016). This is particularly the case in health care, where even after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act health insurance and access to care remained politically contentious and deficient for many. This contributed to declining life expectancy (Reference Harris, Majmundar and BeckerUS National Academy of Medicine, 2021). The USA now provides the lowest level of welfare generosity and the lowest level of health care access of high income democracies (Reference BambraBambra, 2016). Indeed, the relative underperformance of the US social security system has been associated with a reduction of up to four years in life expectancy at the population level (Reference BambraBeckfield & Bambra, 2016).

Thirdly, internationally, collective bargaining and political incorporation have also been associated with national health outcomes. Countries with higher rates of trade union membership have more extensive welfare systems and higher levels of income redistribution – and correspondingly have lower rates of income inequality (Reference Pickett and WilkinsonPickett & Wilkinson, 2010). They also have better health and safety regulations. The USA long had the lowest rate of trade union membership amongst wealthy democracies, restricting the representation of working class interests in policy and politics. For example, in 2010 only 12 per cent of the workforce in the USA was a member of a trade union. In contrast, the rates were 26 per cent in the UK and 68 per cent in Sweden (Reference Schrecker and BambraSchrecker & Bambra, 2015). Further, the political incorporation of minority groups is also robustly associated with better health among those groups, suggesting a direct connection between political empowerment and health (Reference Krieger and RuhoseKrieger & Ruhose, 2013). The USA was a historical laggard in terms of the incorporation of minority groups – with equal civil rights for African-Americans only achieved in the 1960s (Reference Krieger and RuhoseKrieger & Ruhose, 2013).

The combination of all of these political and economic factors helps to explain why the US has a mortality disadvantage relative to other countries and why it has become more pronounced since 1980 (when neoliberal economics led to welfare retrenchment, de-industrialization and deregulation) (Reference Schrecker and BambraSchrecker & Bambra, 2015), arguably leading to the increasing mortality and morbidity rates amongst middle-aged, low income Whites that are now being observed (Reference NavarroNavarro, 2019). By exporting neoliberal policies (e.g. through political/policy transfer and/or trade agreements) that keep wages low and earnings insecure, particularly for those with less education, the USA may also be exporting the conditions which have created ‘deaths of despair’ and increased health inequalities in the USA. Europe may never reach the levels seen in the USA due to differences in the political economy of European health care systems, but the USA may provide a grim forecast of what future European health and ageing crises may look like if Europe also fosters an environment where there is a steady deterioration in economic and social opportunities. This is increasingly a pressing issue in light of the severe economic recession that has followed the coronavirus crisis.

6.4 Conclusion

This chapter has argued that ‘win-lose’ policy choices – policies that are now often discursively framed and advocated in Europe partly as a solution to the ageing crisis – can produce health inequalities across the life-course because they fail to recognize that the cost of ageing today is rooted in health inequalities created in the recent past. Greater health inequalities in the early years will not simply disappear by the time people reach older ages and it is these inequalities in healthy ageing that are the real cost to society. Indeed, policies that deepen inequalities in health among younger groups in order to protect the assumed interests and economic power of older voters are merely exacerbating the future costs of an unequal, ageing population. This has been shown in a devastating manner in relation to the coronavirus pandemic, where countries with a higher burden of chronic disease amongst the elderly have had higher mortality rates. The politics of intergenerational conflict is really after all the politics of inequality.

This politics of intergenerational conflict is not inevitable, however. Our analysis has revealed examples of ‘win-win’ political choices that governments can make to reduce current and future health inequalities – by expanding the social safety net. The solidarity shown across generations in relation to the coronavirus pandemic also gives reason for optimism. We have also shown how ‘win-lose’ policies of austerity and neoliberalism are resulting in increased health inequalities by reducing the social safety net – arguably storing up problems for healthy ageing in the future. This does not mean that such choices are easy. Certainly the path dependence of countries’ political and economic institutions make it hard to simply shift towards health investments across the life-course, especially in settings where tax rises could be unpopular (Reference LynchLynch, 2020). But, as Chapter 3 shows, it is possible to build coalitions – particularly when key socio-demographic groups such as women and unions are effectively mobilized – that promote healthy ageing for all and in the process address the financial burdens imposed through an ageing population.

Acknowledgements

Sections of this chapter are based on Clare Reference BambraBambra (2016) Health Divides: Where You Live Can Kill You, adapted and reproduced with permission of the author and Policy Press. Clare Bambra is a senior investigator in CHAIN: Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research (Norwegian Research Council project number 288638).