Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

8 - Masks and the Order of Things

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

Summary

‘May the gods, the masks and the statues keep us together.’

(Manthia Diawara, in Fölmi 2015: 258. See also Diawara 1998)Masks in the field

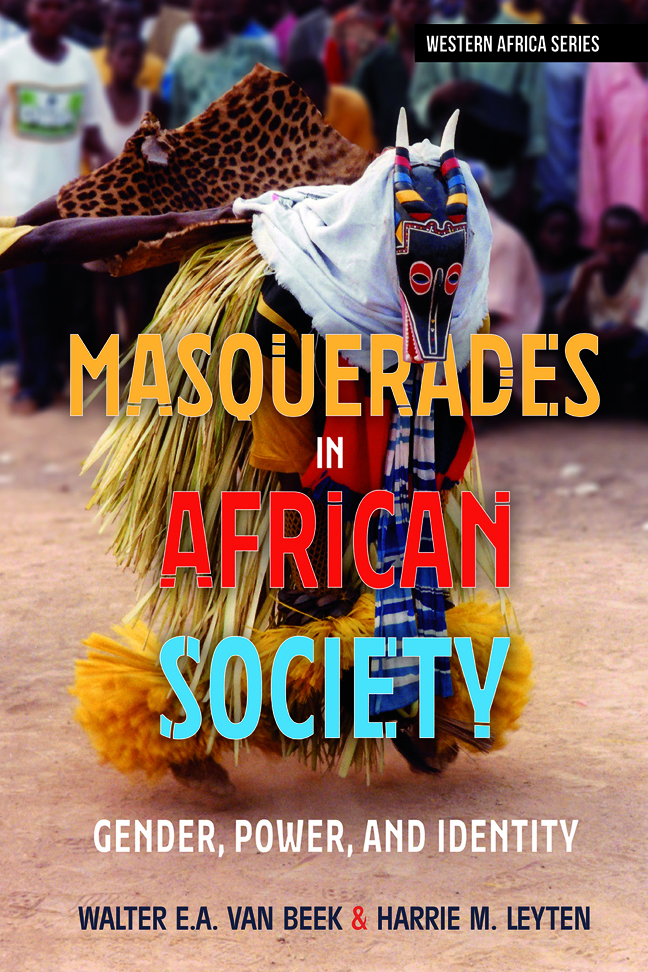

They are easily the most elegant of all mask tops, and anyone interested in African art immediately recognises them: the stylised antelopes called ciwara. As icons of African art they had a lasting influence on European avant-garde artists such as Braque and Picasso. These headpieces are part of the culture of the Bamana, the dominant group in Mali. Nowadays this ciwara is considered a national emblem, and images of the antelope headpiece are routinely mis-used commercially. These striking tops come in many variations and styles, and are arguably among the most intensely studied headpieces of the Mask Crescent. We would not dream of publishing a book on African masks without giving them the attention they so well deserve, and yet they form a curious footnote in the story of masquerading on the continent.

The scene is the village of Dyele in the south of Mali, where the anthropologist Jean-Paul Colleyn has brought a film team to ‘his’ village for a ciwara ceremony. It is the end of March, dry and hot, and the first rains are not due for another three months, but this is the ritual season, and the season for an agricultural rite.

Late on the night of 23 March, the musicians begin to arrive in the village square, which in Bamana culture means quite an ensemble: a huge xylophone, a grating instrument, and four drums of different sizes, plus an iron bell. At the side of the square they start playing, and a group of girls joins them in song: ‘The animals of prey are coming, let them come, give wide berth to the power (nyama) […] the wild animals will swing around’. Suddenly two masks emerge from the dark, dancing to music and songs. Clothed in raffia, their headdresses show the features of the ‘antelope cheval’, the male mask's horns long and high, those of the female mask shorter. The leading male mask dances with two sticks covered in old sacrificial blood. Their first dance is short, just an introductory appearance, and then they sit down at the side. With a crowd gathering and the girls singing, one elder, a dancer of old, takes one of the sticks from the male's hand to serve as a recipient for the coming sacrifices.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Masquerades in African SocietyGender, Power and Identity, pp. 253 - 282Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023