Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Shaping a Legacy

- Part II Rights and Remedies

- 6 “Seg Academies,” Taxes, and Judge Ginsburg

- 7 A More Perfect Union

- 8 Barriers to Entry and Justice Ginsburg’s Criminal Procedure Jurisprudence

- 9 A Liberal Justice’s Limits

- Part III Structuralism

- Part IV The Jurist

- Notes

- Index

7 - A More Perfect Union

Sex, Race, and the VMI Case

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Shaping a Legacy

- Part II Rights and Remedies

- 6 “Seg Academies,” Taxes, and Judge Ginsburg

- 7 A More Perfect Union

- 8 Barriers to Entry and Justice Ginsburg’s Criminal Procedure Jurisprudence

- 9 A Liberal Justice’s Limits

- Part III Structuralism

- Part IV The Jurist

- Notes

- Index

Summary

May 17, 2014, marked the sixtieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. On that day, President Obama issued a proclamation commemorating the decision as “a turning point in America’s journey toward a more perfect Union.” The president noted that Brown not only breathed life into the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment but also provided impetus for the landmark civil rights statutes of the 1960s, most notably, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In so doing, the president declared, the decision “shifted the legal and moral compass of our Nation.”

Yet for all these words of praise, there was an undercurrent running through the president’s proclamation: a suggestion that for too many Americans, the promise of Brown remains just that. The president left it to the First Lady and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan to make this point more explicitly. In a commencement address to graduating high school seniors in Brown’s home city of Topeka, Kansas, Michelle Obama observed that “our schools are as segregated [today] as they were back when Dr. King gave his final speech,” and that “many districts in this country have actually pulled back on efforts to integrate” – with the result that American children are once again attending school “with kids who look just like them.” Arne Duncan echoed these observations. He noted that although Brown ended de jure segregation, it did not end de facto segregation; in fact, many school districts that desegregated in the 1960s and 1970s have since resegregated. Today, 40 percent of black and Latino students attend “intensely segregated schools,” and white students are similarly isolated: only 14 percent attend truly integrated schools. Thus, Duncan concluded that although Brown may once “have seemed like the end of a long struggle for educational equality,” it was actually just the beginning of a struggle that continues to this day.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

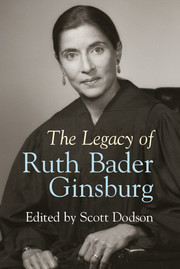

- The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg , pp. 88 - 101Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015