Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- The Logic of an Illusion: Notes on the Genealogy of Intellectual Cinema

- Narcissistic Machines and Erotic Prostheses

- Loïe Fuller and the Art of Motion: Body, Light, Electricity and the Origins of Cinema

- Visitings of Awful Promise: The Cinema Seen from Etna

- Transfiguring the Urban Gray: László Moholy-Nagy’s Film Scenario ‘Dynamic of the Metropolis’

- Eisenstein’s Philosophy of Film

- Knight’s Moves

- Hitchcock and Narrative Suspense: Theory and Practice

- From the Air: A Genealogy of Antonioni’s Modernism

- Dr. Strangelove: or: the Apparatus of Nuclear Warfare

- Collection and Recollection: On Film Itineraries and Museum Walks

- Afterward: A Matter of Time: Analog Versus Digital, the Perennial Question of Shifting Technology and Its Implications for an Experimental Filmmaker’s Odyssey

- Select Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index

- Film Culture in Transition General Editor: Thomas Elsaesser

Dr. Strangelove: or: the Apparatus of Nuclear Warfare

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 January 2021

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- The Logic of an Illusion: Notes on the Genealogy of Intellectual Cinema

- Narcissistic Machines and Erotic Prostheses

- Loïe Fuller and the Art of Motion: Body, Light, Electricity and the Origins of Cinema

- Visitings of Awful Promise: The Cinema Seen from Etna

- Transfiguring the Urban Gray: László Moholy-Nagy’s Film Scenario ‘Dynamic of the Metropolis’

- Eisenstein’s Philosophy of Film

- Knight’s Moves

- Hitchcock and Narrative Suspense: Theory and Practice

- From the Air: A Genealogy of Antonioni’s Modernism

- Dr. Strangelove: or: the Apparatus of Nuclear Warfare

- Collection and Recollection: On Film Itineraries and Museum Walks

- Afterward: A Matter of Time: Analog Versus Digital, the Perennial Question of Shifting Technology and Its Implications for an Experimental Filmmaker’s Odyssey

- Select Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index

- Film Culture in Transition General Editor: Thomas Elsaesser

Summary

DR. STRANGELOVE ‘is the first break in the catatonic cold war trance that has so long held our country in its rigid grip. ‘

Lewis Mumford‘A dysfunctional war machine is inherently self-destructive.’

Manuel de LandaCritics most frequently approach Stanley Kubrick's DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOPWORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964) as a comic satire about the conditions and potential consequences of the continuously escalating nuclear arms race between the United States and the USSR within the ColdWar political assumptions of the early 1960s. Such approaches to the film emphasize its ironic and comically hyperbolic representations of military personnel, politicians, and technocrats as well as the Cold War nuclear age mindset that threatens to trigger a nuclear holocaust. Kubrick's famous explanation of the film's comic mode – that while attempting a straightforward adaptation of Peter George's serious liberal novel Red Alert, he was so struck by the absurdity of the situations he was depicting that satirical hyperbole suggested itself as the only way to do justice to the subject matter – is usually invoked as the key to the film's conception.

Such a critical approach is unquestionably valid and productive. The film brilliantly caricatures the military and political role-players of the 1960s Cold War escalation through its Swiftian use of language and characterization. Ironic disparity between the modern technology of the nuclear apparatus and the anachronistic behavior of characters operating it – for example, cowhand Slim Pickens flying his deadly B-52 bedecked with a ten-gallon hat while giving orders in a folksy Western twang – frequently structures the satire. Grim comedy is derived from the discrepancy between the basic situation in the film (the threat of the annihilation of the human race through atomic warfare) and the habituated and utterly inappropriate ways in which characters react to this reality. General Buck Turgidson, the principal culprit in this respect, protests that it's not fair to condemn the human reliability program just because one general has gone mad and triggered the atomic holocaust. Trying to justify a combat scenario in which ten-twenty million Americans would die, he famously admits, ‘I’m not saying that we won't get our hair mussed.’

- Type

- Chapter

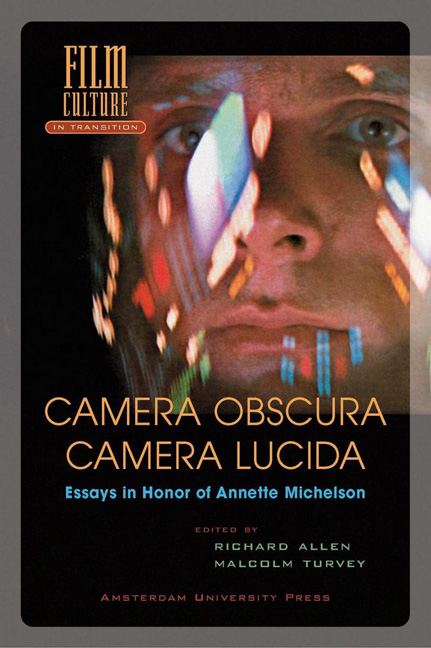

- Information

- Camera Obscura, Camera LucidaEssays in Honor of Annette Michelson, pp. 215 - 230Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2003

- 1

- Cited by